Brian Clegg's Blog, page 70

June 17, 2015

In praise of 'general relativity'

This year marks the centenary of Albert Einstein's groundbreaking general theory of relativity. As the C. P. Snow quote on the back of John Gribbin's excellent book on the topic,

Einstein's Masterwork

points out, 'If Einstein had not created the general theory (in 1915) no one else would have done so... perhaps not for generations.'

This year marks the centenary of Albert Einstein's groundbreaking general theory of relativity. As the C. P. Snow quote on the back of John Gribbin's excellent book on the topic,

Einstein's Masterwork

points out, 'If Einstein had not created the general theory (in 1915) no one else would have done so... perhaps not for generations.'Generally speaking I am in total agreement with Dr Gribbin on all matters scientific (it is dangerous to do otherwise, as he is surely the head of the UK science writing equivalent of Cosa Nostra), but there is one point on which I have to part company.

John gets decidedly vexed when someone refers to 'special relativity' or 'general relativity.' He points out that the correct terms are 'the special theory of relativity' and 'the general theory of relativity', and that the contraction is an abomination, because it is the theory that is special or general, not the relativity.

Now scientists are notoriously picky about definitions to avoid error. But I honestly don't think there is a problem here. No one looks at the word and ponders over exactly what is general or special. And it is a very useful contraction to be able to say 'general relativity' when referring to 'the general theory of relativity', just as we make use of many other contractions to avoid being over-wordy.

The reason this occurred to me is that I had written 'Einstein’s gravitational theory, general relativity' in a book due out later this year. As I was checking the proofs, I thought 'John wouldn't like that.' But it would have read much more clumsily as 'Einstein's gravitational theory, the general theory of relativity.'

I am, technically, without doubt in the wrong. But good communication sometimes benefits from slight bending of precision to gain better effect. So long live special relativity and general relativity.

Now, where are the keys to my fallout shelter?

Published on June 17, 2015 01:15

June 16, 2015

Was he right to try to kill me?

The other day a van driver did his best to splatter me on the road... and I'm not quite sure who was in the right.

The other day a van driver did his best to splatter me on the road... and I'm not quite sure who was in the right.I was at the yellow arrow, about to cross the road dead ahead from one footpath to the other, on my way to the Post Office. That's the kind of exciting daily life I have.

The van had entered the roundabout at the red arrow, heading in my direction.

It's not clear from the picture, but there is a lot of foliage on the roundabout, and it was only when the van reached about the 3 o'clock position that I saw him. By this time I was already part way across the road, though not past the halfway point.

So the question is - did I have right of way or should I have got back off the road? As it was, I carried on and he clearly thought that I shouldn't be there as he showed no sign of slowing down and just missed me.

Clearly he wasn't correct in not slowing down, whoever had right of way, but what I'm not quite sure about is whether I had right of way once I had started across a piece of road with no traffic in sight? Since I can't be bothered to lay my hands on a copy of the Highway Code, I throw it open to your judgement and wisdom...

Published on June 16, 2015 00:28

June 15, 2015

Atheism after Christendom - review

At first sight you might imagine that a book titled Atheism after Christendom, written by Simon Perry the chaplain of Robinson College, Cambridge, might be a throwback to the days when it used to be joked that one thing you could be certain about with trendy Church of England vicars was that they didn't believe in God. But despite the book being in praise of atheism, it also manages to be pro-Christianity, because Perry argues that Christianity is atheist. What's more, he argues that 'New Atheists' like Dawkins and Dennett are actually theists. Confused? You may not agree with the author - and I certainly don't on all counts - but his premise is certainly interesting.

At first sight you might imagine that a book titled Atheism after Christendom, written by Simon Perry the chaplain of Robinson College, Cambridge, might be a throwback to the days when it used to be joked that one thing you could be certain about with trendy Church of England vicars was that they didn't believe in God. But despite the book being in praise of atheism, it also manages to be pro-Christianity, because Perry argues that Christianity is atheist. What's more, he argues that 'New Atheists' like Dawkins and Dennett are actually theists. Confused? You may not agree with the author - and I certainly don't on all counts - but his premise is certainly interesting.There are two keys to that title, because this book depends on very careful use of words. One is 'atheism', of which more in a moment, and the other is 'Christendom'. It's 'after Christendom', not 'after Christianity.' Perry argues that where initially Christianity was considered atheist by the Romans, because it ran counter to the gods of the state - and Perry effectively defines atheism in this way, as denying the gods of your state - with its establishment by Constantine, Christianity became watered down and in that form, as Christendom, provided the state god, so was a worthy target for atheism. However, since the Enlightenment and particularly in a modernist secular society, the Christian god is no longer the god of the state. Instead, Perry suggests, our modernist state gods are Mars and Venus, as represented by everything from military force and shouty domination on the one hand to commerce and greed on the other. (And these are the 'gods' he suggests the New Atheists follow.)

By contrast, Perry suggests, at the heart of Christianity is acceptance of the 'other' - looking outside ourselves rather than inwards, reaching out to the rest of humanity, the universe and its creator (if it has one). And this, he suggests is the real way forward, the only true justification for existence in what otherwise is a short life with little meaning. He suggests that by taking this approach we avoid the errors of deism - suggesting God could exist, but only starting things off before leaving things alone, the god of the gaps - and of theism, where God is constantly interfering, answering random prayers and has to be held to account for all the horrible things in the universe. Perry's God creates the universe in the way it has to be because there is no denying evolution - violent - but is accessible if we begin to truly care for the 'other' - to consider all humanity of equal importance and to live accordingly. It's not, he says, about 'pie in the sky when you die' but about making our world better with this outward looking stance.

Along the way, Perry throws out a lot that will shock many traditional Christians. He suggests that much of the Old Testament, for instance, that makes it clear that God is a nasty, vindictive mass murderer, is a product of a flawed human interpretation by those who wrote it. And I suspect the majority of Christians' beliefs through the centuries will also be considered flawed, influenced as they have been by the strongly theistic picture that has dominated the church for much of its life.

Some of the specifics in the book I have problems with. There is an assumption throughout that this pursuit of 'otherness' is a good thing, and that the modernist individual-centred approach is wrong. I'm not saying I entirely disagree with this, but I never saw any argument to justify this assumption - it is, as far as I can see, a given. If we accept that for a moment, Perry suggests that the Bible, and particularly the New Testament is built on this acceptance of 'the other' - and yet while Judaism may embrace 'the other' in the form of God, it isn't usually considered a religion with such an outward facing approach to other people. Even Jesus demonstrates this: 'The woman came and knelt before him. “Lord, help me!” she said. He replied, “It is not right to take the children’s bread and toss it to the dogs.”' Is that about embracing 'the other'?

Similarly, I struggle with Perry's attitude to science. While I accept that scientists can verge on scientific imperialism as he mentions, and that the really interesting thing about science is not facts but the exploring, I can't really go for the statement that 'science is simply one means of understanding who we are. There are other equally important and no less valid means of experiencing the world.' It's true in a trivial sense - the joy of seeing a sunrise over a beautiful landscape is an 'important and valid means of experiencing the world.' But it isn't comparable to science, it's a totally different thing. And science is uniquely valuable in many ways. Certainly the author gets in a bit of a tangle when he takes on science, telling us that the LHC enables us to produce and trace the paths of quarks (nope), or when he doesn't spot that black holes aren't observed phenomena that challenge general relativity, but rather were predictions of general relativity that may explain observations.

Overall, the book gives the reader a lot to think about. I don't think that it will be of interest to New Atheists, which is a shame, as a lot of what Perry says about the nature of atheism is very insightful, but they would be put off by the amount of the book that is explicitly Christian. (I do wonder if Perry's dismissal of the New Atheist/Western governments' attitude to Islamic terrorism stands up to the atrocities of ISIS.) However, this is a book that all thinking Christians should read (the left wing politics that it's hard to separate from the original version of Christianity might not go down well in some quarters, though). The only danger for them is that, if they accept Perry's view, they may totally change their viewpoint. Is, for instance, going to church more about Christendom than Christianity? (This is something Perry doesn't address explicitly.)

However you look at it, this is a book to challenge the thinking of atheists and Christians alike, and as such is very welcome.

You can find Atheism after Christendom at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com

Published on June 15, 2015 01:19

June 12, 2015

Eleven Minutes Late review

I felt distinctly misled by the blurb on the back of Eleven Minutes Late. I picked the book up from a pile occupying a whole table in a large bookseller, so it must be doing well (especially as I later discovered the book first came out in 2009, and this is only a lightly updated version) and thought it sounded ideal. The bumf made it sound like 'Bill Bryson does the railways' - as a lover of both, I thought it would be excellent. It was very good, but it didn't do what it said on the tin.

I felt distinctly misled by the blurb on the back of Eleven Minutes Late. I picked the book up from a pile occupying a whole table in a large bookseller, so it must be doing well (especially as I later discovered the book first came out in 2009, and this is only a lightly updated version) and thought it sounded ideal. The bumf made it sound like 'Bill Bryson does the railways' - as a lover of both, I thought it would be excellent. It was very good, but it didn't do what it said on the tin.The author Matthew Engel, a journalist with the right kind of connections to be able to interview John Major for the book (probably because Engel had been editor of Wisden's, the cricket almanac) starts in the expected vein, taking us on a trip from Penzance to Thurso with a week's railrover ticket in hand. Just the idea of the ticket really brought back the memories - when I was 15, two friends and I bought these and spent almost all of a week on the railway network. However after a couple of shortish chapters, the book settles down to being an analytical history of the messy development of Britain's railways and it is only a good 200 pages later that he finishes of his journey.

Having said that, if you are interested in railways, the history part is very good. It takes a distinctly cynical dive into the politics of railways and is more about that aspect than the nuts and bolts of the permanent way - which is likely to make it interesting to a wider audience than those who just like trains. Engel gives the reader real (and painful) insights into who the railways are in the shape they are in today by tracing a rarely planned and often brainless set of decisions and ideas, from the original railway mania through to the harebrained privatisation that separated track and trains and constantly pushed train operators to apply higher fares.

In fact, when I read the final section where he returns to travelogue mode, I realised I was glad most of the book was the history, because Engel isn't actually great at the Brysonesque bit. He has a couple of tiny vignettes that are entertaining, one featuring what must be the rudest buffet car (sorry, The Shop) attendant ever, but that apart we just get rather dull descriptions of his journey. Provided, then, you come at this book not expecting what it says on the cover, it is great. I would highly recommend it for its history, although it does leave the regular train traveller so frustrated as it becomes pretty obvious that the British political system is never going to get trains right.

I don't know why, but books about rail disasters have always made great reading. (I'm thinking particularly of Rolt's classic Red for Danger .) This is a book about a different kind of rail disaster - the politics, planning and management of railways and is equally compelling. I realised as I typed that sentence why the blurb was made a bit misleading. Would you sell many books about 'the politics, planning and management of railways'? But in its entertaining, curmudgeonly way, this book does the topic justice while keeping the reader happy.

You can find Eleven Minutes Late at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com - also on Kindle at Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Published on June 12, 2015 01:21

June 11, 2015

Press release of the month

I'm no fan of press release journalism, but sometimes a title catches your eye. I mean, who could resist 'World's largest rat eradication project completes baiting'?

I'm no fan of press release journalism, but sometimes a title catches your eye. I mean, who could resist 'World's largest rat eradication project completes baiting'?So here we go:

On 23 March 2015, despite turbulent sub-Antarctic weather, the final bait pellets were sown via helicopter on the island of South Georgia by an 18-strong group of international specialists known as ‘Team Rat’ in what is the world’s largest rat eradication project to date, funded by small UK-based NGO, the South Georgia Heritage Trust (SGHT).

Only days later South Georgia was announced as the fifth UK Overseas Territory to be included in the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). This ratification to the CBD was significantly aided by the dedication and hard work of the Trust and its commitment to protect the biodiversity of the island, by ridding it of invasive rodents preying on native seabird populations.

South Georgia Heritage Trust and its USA sister organisation Friends of South Georgia Island are hosting a press conference including members of the now returned ‘Team Rat’. The press conference will provide a comprehensive update on the latest phase of the Habitat Restoration Project which successfully spread 95 tonnes of bait over an area of 364 square kilometres, including a 227 kilometre stretch of sinuous coastline.

There remains a further two year monitoring period before the project can be marked a complete success, but it is possible that South Georgia is now rodent-free. There have already been significant discoveries and sightings of native species recovering on the island which will be discussed during the press conference.

Go Team Rat! And 'Boo!' to invasive rodents. Okay, rats can be a serious problem when accidentally introduced into an environment where they have no natural predators. But am I the only one who is highly suspicious about the gratuitous, and not entirely comprehensible use of the word 'ratification' in the second paragraph? Could we have a PR person with a sense of humour? Probably not.

The press conference is on 25 June, so there may be even more excitement at that point.

Published on June 11, 2015 00:17

June 10, 2015

Reviews and reactions

A couple of days ago I blogged about the suspicious nature of very short five star reviews. However, a recent revelation, pointed out by the excellent author Sara Crowe, has made me want to return to the whole business of reviewing - specifically what reviews are for and how, as authors, we ought to respond to them.

A couple of days ago I blogged about the suspicious nature of very short five star reviews. However, a recent revelation, pointed out by the excellent author Sara Crowe, has made me want to return to the whole business of reviewing - specifically what reviews are for and how, as authors, we ought to respond to them.On the matter of what reviews for, I was struck by a response to my earlier post. Someone said 'Most Amazon "reviews" are not actually reviews anyway, they're about whether or not the reader liked the book, which is something different.' I'm not sure I agree with that sentiment. I'd certainly agree that there's little point a review just saying whether or not a reader liked the book - but I do think it's an important part of the mix.

Some while ago I moaned to a major science journal that did book reviews that their reviews were terrible because they never told you if the book was any good at what it purported to do. All each review consisted of (sometimes at length) was a summary of the science covered by the book. But, for me, a review isn't a synopsis. It certainly should give you a feel for what the book covers, but it should equally be about how well it puts across its content - fiction or non-fiction - and what the reading experience is like. Which inevitably overlaps with whether or not the reader likes the book. All reviews are subjective - get over it.

As far as I am concerned, the point of a review is to help a potential reader decide whether or not to read the book. And to do that, yes, it should give an idea of what the book's about - but it's not the review's job to reproduce the content in précis form. Instead it should tell us how well the book puts that content across, any issues with the book and how it delivers on the promise of its puff, the marketing blurb that attempts to sell it. In reading a review we are looking for informed guidance on whether or not the book might work for us.

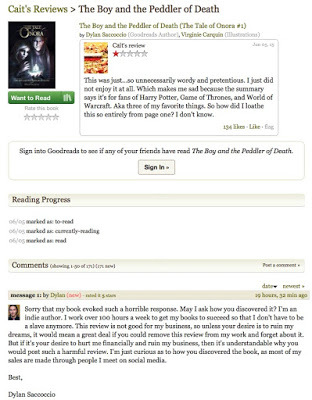

Which leads me onto reactions to reviews by authors. I think anyone who has written a book and got a bad review feels an urge to respond (if they are silly enough to read the bad review in the first place). But the vast majority of us take the intelligent step of restraining ourselves, because it is only going to end in tears. To show how horribly wrong responding can be, we have a wonderful case study in the situation Ms Crowe brought to my attention - a Goodreads review of a book called The Boy and the Peddler of Death. Someone posted a one star review, calling the book wordy and pretentious and saying that it didn't live up to the summary, which suggested it would appeal to fans of Harry Potter, Game of Thrones etc. Now at the time, this book had plenty of good reviews too, and an average star rating of over four.

Unfortunately, the author felt it necessary to wade in and attack the review and the reviewer, digging himself a deeper and deeper hole. At the time of writing, just four days after the review was posted there are 2,062 comments, many of them in direct response to the original review, which alone has 15 pages of replies as more and more Goodreads members waded in to defend the reviewer. And still the author kept on digging. The book now averages two stars, and nearly every recent review gives it one star. The author has committed Goodreads suicide.

Now I have heard elsewhere what a nasty, backbiting place Goodreads is, but this incident isn't really a case of trolling. This is a genuine reaction to a shocked potential audience to the author's inability to take criticism and his remarkable inability to see how much damage he is doing himself. (It didn't help that his defence combined ad hominem attacks with pretentious twaddle.)

Personally speaking I rarely read reviews of my books on Goodreads/Amazon, though I can't resist doing so when a book is reviewed in a newspaper (in part to get pull quotes for my website). But if I do dip in to readers' reviews a) I tend to ignore the low scores and b) I would never think of responding. The only time I ever did so indirectly was to flag a review to Amazon because it contained blatantly incorrect information. All that happened is the same person put a variant of the review back on, adding a complaint that it had been pulled in the first place. So even that was a mistake.

As I've said elsewhere, no one likes to get a bad review. It's hurtful. They're slagging of your baby. But as an author, you make the choice to put yourself out there. No one asked you to. And if you do so, you have to accept that not everyone will like your books, sometimes for really stupid reasons, and get over it. Think nice thoughts. Stroke a dog. Read a compensatory good review. But PLEASE don't reply to the review.

Published on June 10, 2015 01:12

June 9, 2015

Looking in the wrong direction for the next big TV thing

Stuff Magazine gets the wrong messageI read with a total lack of delight in a techie mag that HDR may be the next big thing for TV. Here's my prediction: no it won't.

Stuff Magazine gets the wrong messageI read with a total lack of delight in a techie mag that HDR may be the next big thing for TV. Here's my prediction: no it won't.The fact is that TV makers are really bad at getting into the minds of the ordinary buying public.

We've already seen that disastrously with 3D TV. It is now being phased out, because very few people actually bought it. Very few people could see the benefit.

Now we've got 4K TV (with a lot more pixels) and HDR (standing for High Dynamic Range) vying to be the next next big thing. And I'm not sure they are going to succeed either.

The benefit of 4K is getting far higher resolution images than the current HD, while HDR, an effect you'll find on most modern camera phones, zaps up the contrast, making it less likely that parts of an image will wash out, though in exchange it can produce some very artificial looking colour palettes with an unnaturally rich mix of colours - it has a tendency to make reality look artificial.

Why am I doubtful? Because for the typical, say, 40 inch screen, most viewers are perfectly happy with the picture quality on an ordinary HD TV. In fact many of us don't even care about using the best of that. I can watch the main channels in ordinary broadcast quality or HD - usually I just watch ordinary because I can't be bothered to scroll down to the HD channels. You can see the difference in picture quality if you look for it, but if you are actually watching a programme or film, you don't notice it.

There is no doubt we needed to get to current basic levels to cope with modern screen sizes. But unless the typical screen size goes up to about 60 inch, we really don't get a lot of benefit from going beyond standard HD, and at current sizes, even that isn't really necessary. The fact that you only notice the HD if it's a bad programme/film, so it doesn't grab your intention and you instead spend your time studying the quality of the image, says a lot for how much benefit it delivers.

I'm not sure what the next big thing is for TV - but I don't think it will be about an even flashier image quality. It's far more like to be about getting the back end right - cracking the integration, for instance, of streaming services like Netflix into the user interface, so you don't have to switch from broadcast to iPlayer to Netflix to Amazon Prime, but instead simply look through what's available across the patch that you've subscribed to.

Sorry, TV makers. But 'Mine is bigger [resolution] than yours' isn't a winning game.

Published on June 09, 2015 01:38

June 8, 2015

The dark side of Amazon reviews

Spot the suspicious reviewsLike any other author I am delighted by good reviews and deeply saddened and wounded by bad ones. And amongst those we have to take very seriously these days are Amazon reviews. It might seem that a good review in, say, a national Sunday paper is far more important than a collection of good reviews on Amazon. And that's true over the weekend the paper was published. In fact when one of my books had huge, enthusiastic reviews in the Sunday Times and the Mail on Sunday it positively shot up the sales rankings. However, such reviews are transient.

Spot the suspicious reviewsLike any other author I am delighted by good reviews and deeply saddened and wounded by bad ones. And amongst those we have to take very seriously these days are Amazon reviews. It might seem that a good review in, say, a national Sunday paper is far more important than a collection of good reviews on Amazon. And that's true over the weekend the paper was published. In fact when one of my books had huge, enthusiastic reviews in the Sunday Times and the Mail on Sunday it positively shot up the sales rankings. However, such reviews are transient.Over time a book will build up a collection of Amazon reviews, and that will be the first point of assessment for many a potential reader. Such reviews probably weigh less for books than, say, reviews of a slow cooker, because as a reader you may well know an author's work and be quite happy to get another book from the same source. However, for many, the Amazon reviews will still be extremely important. We shouldn't read too much into a single review, but when there are plenty, it's usually possible to get a feel for what a book is like.

I've just posted one of my rare very bad reviews, of Stephen Fry's latest autobiography More Fool Me (you can see my review here, but for our purposes, the important thing is it's also posted on Amazon).

Now if you take a look at the Amazon page (I'll give you a link in a moment, but hang on til you've heard the argument), you'll see that all the major reviews - the ones that most people found useful - are one or two star and slagging the book off, just as I did. Frankly, it's very disappointing. But you will also see something rather odd. Although the lead reviews are all negative, the book actually has more five star reviews than any other - 118 five star to 66 at 2 star and 71 at one star. This is the reason it averages three stars, despite so many bad reviews. How could so many people rate such a bad book so highly?

Now take a look at the 'recent customer reviews' down the side of the page (extract shown above). All the five star reviews are just a word or two (apart from one, who doesn't understand the Amazon review system and is actually rating the price and delivery). If you click through to see all the five star reviews, there are certainly some genuine ones - people who just don't agree with readers who have taste, and that's fine. But there also a fair number that are just one or two words.

It could be just a coincidence that a lot of the people who like a book aren't particularly forthcoming as to why they like it. But there is another possible reason. Just like you can buy Facebook likes or Twitter follows, there are companies that will provide you with a set of good Amazon reviews. So if a publisher, for instance, is unhappy by how many negative reviews they are getting, they can balance them out with some cheap and cheerful good ones.

Now I need to stress that I am not saying that this was the case with More Fool Me; I am sure that the short five star reviews are purely coincidental here. But when there are so many short positive reviews (and some are by people who haven't reviewed any other books, or who title their review 'Five Stars' or who only ever leave four/five star reviews) it does look odd.

The way that the Amazon algorithm has shuffled them off to one side in favour of the decent quality reviews is a good lesson for anyone tempted to buy five star reviews - don't waste your money, because they aren't convincing. It's the same with the spam comments you get on a blog. They try to make them sound like real people making real comments, but they sound fake.

I must emphasize, of course, that a short review is not necessarily fake. I was intending to review this book with the single word 'Yawn', but my natural inclination to write overcame the urge. However, get a collection of them on a book that is otherwise being slated and, not surprisingly, people will be suspicious. Click through here and scroll down to the bottom for the reviews to see the effect.

Published on June 08, 2015 02:52

June 7, 2015

More Fool Me review

Yawn. Don't bother. Self indulgent stuff. Which is a shame, because I liked Stephen Fry's second autobiography.

Yawn. Don't bother. Self indulgent stuff. Which is a shame, because I liked Stephen Fry's second autobiography.I really wonder if the Observer reviewer was reading the same book when (s)he said 'A beautifully erudite and richly entertaining page-turner,' unless they trimmed off 'this isn't.'

One of only four books I've ever given up part way through.

I'm not even giving you links to Amazon. It wouldn't be fair.

Published on June 07, 2015 05:22

June 4, 2015

Quantum Age Comes of Age

I spent a nervous few minutes this morning in the BBC's Swindon NCA studio, connected down the ISDN line (remember ISDN) to London to appear on the UK's flagship current affairs radio programme, Today, being grilled by the inestimable John Humphrys. Thankfully he didn't want to ask me about David Cameron's performance so far, or the antics of Sepp Blatter and friends, but instead we talked about my book

The Quantum Age

, which is out in paperback today.

I spent a nervous few minutes this morning in the BBC's Swindon NCA studio, connected down the ISDN line (remember ISDN) to London to appear on the UK's flagship current affairs radio programme, Today, being grilled by the inestimable John Humphrys. Thankfully he didn't want to ask me about David Cameron's performance so far, or the antics of Sepp Blatter and friends, but instead we talked about my book

The Quantum Age

, which is out in paperback today.It has quickly become a favourite of my output, both because I love the weirdness of quantum physics - and I have fun exploring that - but also because few of us really think about the impact that quantum physics makes on our everyday life.

At a trivial level, pretty well everything is down to quantum physics, as matter, light and electricity (to name but three essentials) are all quantum based. But there is a more significant reason for calling this the Quantum Age, just as the nineteenth century was the Steam Age. Because are remarkable 35% (or thereabouts - no one seems to be able to trace the source of this figure) of GDP in developed countries would not exist without making explicit use of quantum physics.

So, for instance all electronics - computers, mobile phones, TV, radio, plus all the places electronics has reached into from washing machines to cars - required an understanding of quantum physics in the original design of the electronics. And some - flash memory, for instance, that enables your phone to remember stuff when the battery is dead - makes use of really weird quantum behaviour: in this case, quantum tunnelling, where a quantum particle jumps straight from being on one side of a barrier to the other without passing through the space in between.

What's more, electronics is just the beginning. Lasers and superconductors, for instance, both make use of particular quantum effects. Lasers are already well embedded in our lives. (I reckon I've at least 10 in my house.) At the moment superconductors, which lack any electrical resistance and so can support massive currents and magnetic fields, are mostly used in specialist applications like the LHC, MRI scanners and magnetic levitation trains - but the closer we get to room temperature superconductors, the more applications there are likely to be. And other quantum weirdos, like SQUIDs and quantum computers are waiting on the horizon.

The fact is that quantum physics has had a huge impact on our lives, and that impact is only like to grow. Something I hope that The Quantum Age really celebrates and explains.

Since this is, in part, a celebration of the BBC's quantum revolution, I'll just finish off with another chance to see my little adventure with the BBC's Robert Peston, attempting to explain why quantum physics is so remarkable:

Published on June 04, 2015 02:37