Brian Clegg's Blog, page 124

March 6, 2013

Scientists as celebs?

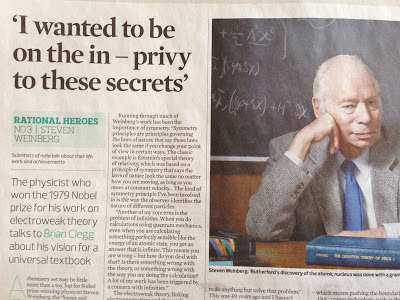

The interview that started it allI recently had the privilege of interviewing Nobel Prize winner Steven Weinberg for the Observer.

The interview that started it allI recently had the privilege of interviewing Nobel Prize winner Steven Weinberg for the Observer.One of the commenters for the online version remarked 'If only the world took more interest in Physics Nobel Laureates and less interest in celebrity lives/murders or royal baby bumps.' Ah, so true. And I couldn't help thinking what a science version of the celebrity gossip magazine Heat - perhaps called Thermodynamics! - would be like.

I think, in all fairness to our favourite scientists, it would be rather dull. The commenter was making the point that scientists are more worthy than celebrities because they have actually done something amazing, rather than just being known for being known.

However, if you turn this around, you can see there's a fatal flaw in the reasoning that would condemn Thermodynamics! before it got off the ground. Because, on the whole, we don't know scientists. It's not that they don't have their fair share of juicy life stories, triumphs and disasters. Just take a look at a biography of Richard Feynman, for instance. But the reason people want to read Heat magazine is that these are stories about people they feel they know. People they would recognize if they saw them on the street. It's the modern day equivalent of the latest village tittle tattle. But the fact is, we don't know scientists. To be honest, I had no idea what Steven Weinberg looked like before this week. So why would we care?

It's a human thing, I afraid. Of course there are scientists etc. we know off the TV - they could feature in Thermodynamics!... but only again because we know them, not because of their scientific achievements. Can any Brian Cox fan tell me about a single significant piece of science he has done? I thought not.

Sadly, it's an exercise that's doomed to failure. But it was fun to think about it.

Published on March 06, 2013 00:21

March 5, 2013

Appearing on University Challenge

Last night one of my daughters asked if I'd been on University Challenge. I said 'No,' but ironically within minutes I was receiving phone calls to tell me that I had been. Sort of. Somewhat bizarrely I was the subject of a question on this venerable BBC quiz show. Take a look:

Slightly shocked does not come close to describing it. Gobsmacked was closer. I must admit I wish that two out of three of the books listed weren't amongst my more obscure titles. And it would have been fun if the team had got the answer right. Even so, it's rather a nice feeling...

Slightly shocked does not come close to describing it. Gobsmacked was closer. I must admit I wish that two out of three of the books listed weren't amongst my more obscure titles. And it would have been fun if the team had got the answer right. Even so, it's rather a nice feeling...

Published on March 05, 2013 00:59

March 4, 2013

I want to write popular science

If this is the expectation, don't botherLast week I received a rather strange phone call. 'Is that the popular science website?' a female Scottish voice asked. I don't get phone calls for www.popularscience.co.uk so I rather hesitantly said 'Yes.'

If this is the expectation, don't botherLast week I received a rather strange phone call. 'Is that the popular science website?' a female Scottish voice asked. I don't get phone calls for www.popularscience.co.uk so I rather hesitantly said 'Yes.''Do I need a degree to write popular science books?' came the reply. The conversation went on this vein for about 5 minutes. Inevitably afterwards I thought of a key question I should have asked her - 'Why do you want to write popular science books?' But I didn't.

My caller was a member of her local astronomical society, but had no qualifications. So what is the answer? Is enthusiasm enough? My reply had to be rather vague. It was a definite maybe. If you are going to write a book about heavy duty physics, I suspect a degree is the minimum qualification to have a reasonable chance of getting the message right. If, however, you are going to write a book about the joys of stargazing, then it certainly isn't a prerequisite. But that doesn't mean that it's enough to simply want to write a popular science book to do it well.

Anyone can, of course, write such a book and self publish it, or pay an arm and a leg for a vanity publisher to do it for them. But that doesn't mean the book will be any good, or that any one will read it. And whether you go down the self-publishing route or a more conventional one it would be sensible to apply the same criteria that a publisher would in taking a look at your proposal.

They would ask questions like:

Why you? You may not have a degree, but what makes you a good person to write this book? What is your experience? What can you bring to it? We need a little more that 'I'm a member of my astronomical society.'Is what you want to write about interesting to other people? You may be fascinated by a ten year study of the brightness of a single variable star, but the audience for such a book would be pretty limited. What is there going to be in your book that will get people interested?Can you write? In many ways this is the clincher. It's easy to think 'Well, anyone can write. I wrote stuff at school.' But there's a world of difference between being able to put words on a piece of paper and being able to get a science topic across engagingly - as many a professor attempting to write a popular book has discovered. This is a particularly difficult one as, frankly, you have little idea of your own ability. Nor do your friends and relatives (unless they work in publishing and are dangerously honest). If possible you need to get an unbiassed external assessment. One way to do this is just to send your stuff off to a publisher and see what happens.*It's a painful process, but a necessary one.

As I mentioned, I regret I also didn't ask that key question 'Why?' If you want to write a popular science book because you heard Stephen Hawking made millions from A Brief History of Time, forget it. Most popular science books probably earn their author a couple of thousand pounds for a lot of work - certainly less than minimum wage. If it's because you want to get on TV and be the next Brian Cox, doubly so forget it. If you have your own scientific theories (probably proving Einstein wrong) that you know the world would be dying to hear - take a reality check. The world does not want to hear. I would only recommend it if the topic fascinates you and you have an urge to share that fascination - and have a certain talent in getting that excitement and fascination across. You don't necessarily need a degree to write a popular science book, but there are some things you can't do without.

* When it comes to the stuff to send, it is important to get it right. I've a little free downloadable guide on this website that describes the package that should be sent as a proposal.

Published on March 04, 2013 01:05

March 1, 2013

Putting the drops in the opsin

My latest podcast for the Royal Society of Chemistry takes a trip into your eyes and the remarkable compounds - opsins - that give you the ability to see.

My latest podcast for the Royal Society of Chemistry takes a trip into your eyes and the remarkable compounds - opsins - that give you the ability to see.Probably the best known of the opsins is rhodopsin. The 'rhod' part of the name, spelled R-H-O-D, comes from a Latin root meaning 'rosy', reflecting rhodopsin's purplish-red coloration - it is sometimes called 'visual purple.' However the name is doubly apt, because rhodopsin is found in a particular type of cell in animal retinas - the rod. But there's plenty more to find out, so hurry along to the RSC compounds site - or if you've five minutes to spare now, click to to have a listen to my podcast on opsins.

Published on March 01, 2013 00:20

February 27, 2013

Spaced out

** Grumpy old man alert **

A genuine web formThere's a campaign in the US saying that every student should have the opportunity to learn to write computer code. And I agree - it is a great thing to be able to do. However I do warn people who take that step into coding that it may turn them into a grumpy person, when they know how easy it is to do something... yet discover that so many idiot coders have failed to do so.

A genuine web formThere's a campaign in the US saying that every student should have the opportunity to learn to write computer code. And I agree - it is a great thing to be able to do. However I do warn people who take that step into coding that it may turn them into a grumpy person, when they know how easy it is to do something... yet discover that so many idiot coders have failed to do so.

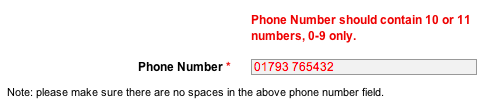

My particular gripe today is web forms that ask for telephone numbers. The standard format for a phone number in the UK is something like '01793 765432' with a dialling code, a space, and the local number. Of course you don't type the space into your phone, but it is the correct format. Yet increasingly web forms are rejecting phone numbers with spaces in. Use one and you will get an error message pointing out the folly of your ways.

But here's the thing, and the reason why I bring up coding skills in the same breath. Once upon a time I used to write code in C, the programming language (in various variants) most used to write software for personal computers. In C there is a standard, built-in function that does a pretty simple, but occasionally useful thing. It takes a string of characters and returns that same string with the spaces removed. That's all it does. Frankly it's easy enough to write yourself, but it usually comes in the library of functions. Plain and simple. So guess what? If you have a form and put the text in it through this routine, you will get a phone number without spaces. No need to wrap the user on the knuckles for getting it right - simply change the format to the one you want.

This is a fundamental of good user interface design. If you know what's wrong, don't complain, just fix it. If your programming can't cope with the input it's your fault, not the users.

Get your act together guys. This is pathetic.

A genuine web formThere's a campaign in the US saying that every student should have the opportunity to learn to write computer code. And I agree - it is a great thing to be able to do. However I do warn people who take that step into coding that it may turn them into a grumpy person, when they know how easy it is to do something... yet discover that so many idiot coders have failed to do so.

A genuine web formThere's a campaign in the US saying that every student should have the opportunity to learn to write computer code. And I agree - it is a great thing to be able to do. However I do warn people who take that step into coding that it may turn them into a grumpy person, when they know how easy it is to do something... yet discover that so many idiot coders have failed to do so.My particular gripe today is web forms that ask for telephone numbers. The standard format for a phone number in the UK is something like '01793 765432' with a dialling code, a space, and the local number. Of course you don't type the space into your phone, but it is the correct format. Yet increasingly web forms are rejecting phone numbers with spaces in. Use one and you will get an error message pointing out the folly of your ways.

But here's the thing, and the reason why I bring up coding skills in the same breath. Once upon a time I used to write code in C, the programming language (in various variants) most used to write software for personal computers. In C there is a standard, built-in function that does a pretty simple, but occasionally useful thing. It takes a string of characters and returns that same string with the spaces removed. That's all it does. Frankly it's easy enough to write yourself, but it usually comes in the library of functions. Plain and simple. So guess what? If you have a form and put the text in it through this routine, you will get a phone number without spaces. No need to wrap the user on the knuckles for getting it right - simply change the format to the one you want.

This is a fundamental of good user interface design. If you know what's wrong, don't complain, just fix it. If your programming can't cope with the input it's your fault, not the users.

Get your act together guys. This is pathetic.

Published on February 27, 2013 23:08

Why green heretics are essential

You may recall a little while ago I rather revelled in being labelled a 'green heretic'. I've just come across a report that emphasises why it is so important to indulge in a little green heresy (hopefully dodging the green inquisition) and think beyond the knee-jerk reaction as I suggest we should in

Ecologic

.

You may recall a little while ago I rather revelled in being labelled a 'green heretic'. I've just come across a report that emphasises why it is so important to indulge in a little green heresy (hopefully dodging the green inquisition) and think beyond the knee-jerk reaction as I suggest we should in

Ecologic

.According to this piece in the The Register (usually more a source of great IT information), climate change isn't high on ordinary people's priorities. Well, that's not surprising at the moment with worldwide recession and financial difficulties. When you are trying to keep your business afloat, or to keep your house from being repossessed and your children fed, it is difficult to pay too much attention to the finer points of improving the environment - important though they remain. But the interesting thing about the data discussed in that article is that people gave climate change a similarly low importance when times were good. It's not just politicians that have a short term view - so do the rest of us, apart from a vocal few.

This isn't, by the way, a matter of climate change denial - it is rather accepting that things are the way they are, but not being prepared to do anything much about it. There's a strong parallel with the overweight/obesity situation in the Western world. Most of us know perfectly well that eating too much fat and sugar is going to make us overweight. We don't deny it. But we can't resist the siren call of fish and chips or pizza, or hamburgers and a coke, or whatever our high fat, high sugar diet of choice is. Because each incremental meal doesn't really make much difference. The impact is from long term use, but the experience is short term, one meal at a time.

Those who call people like me green heretics argue that we put too much stock on engineering ourselves out of trouble. They say that we have too much faith in science and technology to counter our mistreatment of the environment. But this survey says to me that such people have got things back to front. Because short of draconian restrictions from government, something that isn't going to happen in a democracy if said government wants to be re-elected, we are not going to change our ways. Why would we, if we don't consider it a priority? We consume our energy in small chunks, just like those hamburgers. So the faith in science and technology solutions aren't based an overweening belief in the power of science, they are instead our only hope.

I'm not saying give up your recycling, or everyone should go out and buy a Hummer. Of course we can and should still do as much as we can as individuals to counter climate change. But it clearly isn't going to be anywhere enough. We aren't going to radically change the way we live our lives because it will help with climate change in the future. It is just not going to happen. And so we have to find science and engineering solutions to counter the way we live. And the sooner we put more effort into that, the better.

Published on February 27, 2013 00:43

February 26, 2013

Communicate, communicate, communicate

Yesterday I had a phone call from the company that makes the accounting software I use. Apparently they want to expand their offering and wondered if I'd be interested in, for instance, a CRM system. I told them politely NTY.

You can do it if you communicate

You can do it if you communicate

(If you aren't au fait with TLAs (three letter acronyms), CRM is 'Customer Relationship Management' - in essence a database of your customers that enables you to give the impression of knowing them to some extent. I made up NTY - 'no thank you.')

I have two types of customer - big direct people like publishers and smaller (in terms of income, though obviously hugely important) indirect people like book readers. Neither of these really fit the CRM profile. I only interact with a handful of publishers - a 'to do' list (I use Apple's Reminders) is fine for that. As far as readers go it's a very ad-hoc relationship that doesn't need that kind of management.

However, the whole business made me think about customer service, something I used to major on in my airline days. I even wrote a (rather good) book about it. But in all honesty, and at risk of sounding like Tony Blair, there are just three things you first need to concentrate on to improve customer service/relations - communicate, communicate and communicate. It's ridiculously simple, and yet so many companies are really bad at it.

Absolutely the most important time for this is when things go wrong. This is why airlines/airports often have a terrible customer service reputation. Because when things go wrong they don't communicate quickly or frequently enough. I've had a really good example recently of a company not quite getting it right.

The company that hosts my websites/mail servers, Webfusion generally is very good. But for over 24 hours now, the server that hosts many of my websites and all my frequently used email addresses has been totally out of action. This is a long time to be offline - and the only way to come out of it smelling of roses is for Webfusion to communicate a lot. So how have they done?

First fail: they didn't let me know that the server was down, I had to find out the hard way. Of course they couldn't email me on my regular address - but they should have both a backup address and, crucially, a number they can text an alert to. Simple, easy to do, informative.

Second partial success: they have a support site with a status page. This has been giving updates of progress (or lack of it). That's good. But it has not been done well enough. The updates have been too infrequent and give no timescale for the next information. I'd suggest every two hours is a sensible period, and each update should tell you when the next one will be up. (And, of course, that next one mustn't be late.)

Third fail: they raised hopes then dashed them. Bad move. Last night at around 10pm they posted a message saying 'We are performing final checks on the system with a view to have the server back online as soon as possible.' This made it sound as if it was about to come back any minute, but it still wasn't working at 8am next morning. A supplementary message wasn't posted until 8.43am.

As of 8.46am when I write this, the server is still not back, so as well as continuing communication with more information content (the latest message is still very much a holding one with no idea of timescale/what's happening), I don't yet know what they will do when it's fixed. There is the biggest challenge of all. I suspect they will just issue a 'Sorry, but it's fixed now,' message. That really won't do. After a failure like this, the final communication should offer some kind of compensation too - and generous at that. This is the point you can turn a disaster into a triumph, but not if you are careless about communicating or stingy with your recompense.

So there we have it. Communicate, communicate, communicate. Simples.

You can do it if you communicate

You can do it if you communicate(If you aren't au fait with TLAs (three letter acronyms), CRM is 'Customer Relationship Management' - in essence a database of your customers that enables you to give the impression of knowing them to some extent. I made up NTY - 'no thank you.')

I have two types of customer - big direct people like publishers and smaller (in terms of income, though obviously hugely important) indirect people like book readers. Neither of these really fit the CRM profile. I only interact with a handful of publishers - a 'to do' list (I use Apple's Reminders) is fine for that. As far as readers go it's a very ad-hoc relationship that doesn't need that kind of management.

However, the whole business made me think about customer service, something I used to major on in my airline days. I even wrote a (rather good) book about it. But in all honesty, and at risk of sounding like Tony Blair, there are just three things you first need to concentrate on to improve customer service/relations - communicate, communicate and communicate. It's ridiculously simple, and yet so many companies are really bad at it.

Absolutely the most important time for this is when things go wrong. This is why airlines/airports often have a terrible customer service reputation. Because when things go wrong they don't communicate quickly or frequently enough. I've had a really good example recently of a company not quite getting it right.

The company that hosts my websites/mail servers, Webfusion generally is very good. But for over 24 hours now, the server that hosts many of my websites and all my frequently used email addresses has been totally out of action. This is a long time to be offline - and the only way to come out of it smelling of roses is for Webfusion to communicate a lot. So how have they done?

First fail: they didn't let me know that the server was down, I had to find out the hard way. Of course they couldn't email me on my regular address - but they should have both a backup address and, crucially, a number they can text an alert to. Simple, easy to do, informative.

Second partial success: they have a support site with a status page. This has been giving updates of progress (or lack of it). That's good. But it has not been done well enough. The updates have been too infrequent and give no timescale for the next information. I'd suggest every two hours is a sensible period, and each update should tell you when the next one will be up. (And, of course, that next one mustn't be late.)

Third fail: they raised hopes then dashed them. Bad move. Last night at around 10pm they posted a message saying 'We are performing final checks on the system with a view to have the server back online as soon as possible.' This made it sound as if it was about to come back any minute, but it still wasn't working at 8am next morning. A supplementary message wasn't posted until 8.43am.

As of 8.46am when I write this, the server is still not back, so as well as continuing communication with more information content (the latest message is still very much a holding one with no idea of timescale/what's happening), I don't yet know what they will do when it's fixed. There is the biggest challenge of all. I suspect they will just issue a 'Sorry, but it's fixed now,' message. That really won't do. After a failure like this, the final communication should offer some kind of compensation too - and generous at that. This is the point you can turn a disaster into a triumph, but not if you are careless about communicating or stingy with your recompense.

So there we have it. Communicate, communicate, communicate. Simples.

Published on February 26, 2013 00:57

February 25, 2013

Cloudy working

Have you managed to ignore the concept of 'the cloud' on your computer so far? If so, could I politely suggest that you are bonkers?

Have you managed to ignore the concept of 'the cloud' on your computer so far? If so, could I politely suggest that you are bonkers?Let's think of a humble file on my computer - say an article I've spent hours writing. Let's think of the pre-cloud me working with it. What happens if my computer hard disc dies horribly? Well, I will have backed it up. Probably. Certainly within the last week. Shame I only wrote it yesterday. Or let's imagine I'm 50 miles from home and suddenly need to access it. Well, tough. I can't.

Now let's think of post-cloud me. My hard disc dies? No problem, the latest version of the article is in the cloud and I can access it from any other computer. Need to get it remotely? No problem again. I can get to it from my phone, my iPad or a computer.

But isn't it complicated/expensive? No! It isn't. It's simple and for the kind of space you need for documents (if not photos and music) it's free.

The main cloud storage facilities work by setting up a new folder on your computer. Put anything in that folder and it is automatically duplicated in the cloud. Any changes are synchronized. That's all there is to it. Of course you have to slightly change your way of working, in that your documents will sit in that folder rather than your computer's Documents or My Documents folder - but that's hardly a chore.

The main cloud storage facilities work by setting up a new folder on your computer. Put anything in that folder and it is automatically duplicated in the cloud. Any changes are synchronized. That's all there is to it. Of course you have to slightly change your way of working, in that your documents will sit in that folder rather than your computer's Documents or My Documents folder - but that's hardly a chore.Personally I use three free cloud services - Dropbox, Google Drive and SkyDrive (Microsoft's version). They come with 2 Gb, 5 Gb and 7 Gb of free storage respectively - plenty for any document work. There's not a huge amount to choose between them in practice, though each offers subtly different features (you can see a useful comparison here). I would tend to recommend SkyDrive for Microsoft Office documents as the web version has built in Office editing tools, so you can tweak a document even if you don't have access to Office. There's no reason to use all three particularly, though I find it quite useful having different spaces for different types of documents.

If you want to go the whole hog and have all your photos and music up there, you can do that too, though typically you would go over these limits and need to pay an annual fee for extra space.

I come back to my original statement. If you aren't using one of these services, why not, short of inertia and folly? Rush out and do it today. Bear in mind that you are not tying yourself into only having access to your files when you have internet access. The folder is actually on your computer, it only synchronizes with a copy in the cloud. But why would you want to miss out on automated instant backup and the ability to access your files away from home?

Published on February 25, 2013 00:35

February 22, 2013

Where's quantum Wally?

It's appropriate that the episode of The Big Bang Theory I watched last night featured as part of a kind of nerd Olympics a competitive game of Where's Wally (or to be precise, the US variant of the book Where's Waldo? - why did they change the name?) where contestants were handicapped by playing without their glasses. There's something very Where's Wally? like about my topic today, which is the puzzle of where a quantum particle like an electron or a photon is when you aren't looking at it.

Here's the thing. Unless you observe it and pin it down, a quantum particle's location is fuzzy. The position is described by Schrödinger equation, which tells you the probability of it being in any location, but this isn't like saying I can give a probability for where I am in the house, because in practice I actually will be in one, specific place at any one time. In the case of the quantum particle the probability is all there is. The best we can say is the particle literally doesn't have a fixed location, we can only say that there are various probabilities of where we would find it if we looked.

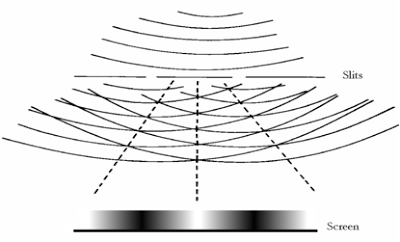

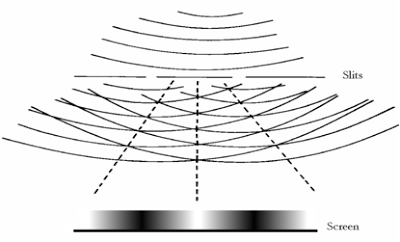

Young's slitsSo far so good. This fuzziness of location is important, because it explains why it is easy to think that quantum particles are, in fact, waves. The classic example is Young's slits. A couple of hundred years ago, Thomas Young set light through a pair of slits so that the beams merged on a screen behind them. The result was a series of light and dark bands. This was used to show that light is a wave, because waves 'interfere' with each other. If two waves meet and they are both rippling up at the same point, the result will be a bigger wave. If one is rippling up and the other down, they will cancel each other out. And for light this would produce those dark and light bands.

Young's slitsSo far so good. This fuzziness of location is important, because it explains why it is easy to think that quantum particles are, in fact, waves. The classic example is Young's slits. A couple of hundred years ago, Thomas Young set light through a pair of slits so that the beams merged on a screen behind them. The result was a series of light and dark bands. This was used to show that light is a wave, because waves 'interfere' with each other. If two waves meet and they are both rippling up at the same point, the result will be a bigger wave. If one is rippling up and the other down, they will cancel each other out. And for light this would produce those dark and light bands.

The only thing is, we now know that light can be described as quantum particles - photons. And even if you send those one at a time through Young's slits, the interference pattern still builds up. The same goes for other quantum particles like electrons, which produce exactly the same effect.

The reason I bring this up now is I am currently reading for review a book called The Quantum Divide, which is about half way between a popular science book and a student text, and which takes some offence at the way this quantum strangeness is often portrayed. What popular science books frequently say, and I think I have been guilty of this, is that a particle goes through both slits (i.e. is in more than one place at a time) and interferes with itself. Gerry and Bruno (I'm not being overly familiar, these are surnames), the authors of the book, take serious umbrage at this wording:

The idea that, say, a photon goes through both slits and interferes with itself is technically inaccurate. The photon is not in any place with certainty, but is only described by the wave equation, which gives it a probability of being located in each slit. And the interference is of that probability wave, not the photon itself. However it is arguable that the probability wave is the photon - that it is the only meaningful description of the photon and as such if we say that the probability wave has values at both slits and interferes with itself, we are surely not stretching things too far to replace the clumsy 'the probability wave' with 'the photon'.

Okay, it's not perfectly accurate, and we certainly should explain what we are doing and probably often fail to do so. But I don't think this is any more a problem than when physicists speak of the big bang or dark matter as if it they are facts, rather than our current best accepted theories. To make a big thing of it as G&B do is, frankly, to miss the point.

Here's the thing. Unless you observe it and pin it down, a quantum particle's location is fuzzy. The position is described by Schrödinger equation, which tells you the probability of it being in any location, but this isn't like saying I can give a probability for where I am in the house, because in practice I actually will be in one, specific place at any one time. In the case of the quantum particle the probability is all there is. The best we can say is the particle literally doesn't have a fixed location, we can only say that there are various probabilities of where we would find it if we looked.

Young's slitsSo far so good. This fuzziness of location is important, because it explains why it is easy to think that quantum particles are, in fact, waves. The classic example is Young's slits. A couple of hundred years ago, Thomas Young set light through a pair of slits so that the beams merged on a screen behind them. The result was a series of light and dark bands. This was used to show that light is a wave, because waves 'interfere' with each other. If two waves meet and they are both rippling up at the same point, the result will be a bigger wave. If one is rippling up and the other down, they will cancel each other out. And for light this would produce those dark and light bands.

Young's slitsSo far so good. This fuzziness of location is important, because it explains why it is easy to think that quantum particles are, in fact, waves. The classic example is Young's slits. A couple of hundred years ago, Thomas Young set light through a pair of slits so that the beams merged on a screen behind them. The result was a series of light and dark bands. This was used to show that light is a wave, because waves 'interfere' with each other. If two waves meet and they are both rippling up at the same point, the result will be a bigger wave. If one is rippling up and the other down, they will cancel each other out. And for light this would produce those dark and light bands.The only thing is, we now know that light can be described as quantum particles - photons. And even if you send those one at a time through Young's slits, the interference pattern still builds up. The same goes for other quantum particles like electrons, which produce exactly the same effect.

The reason I bring this up now is I am currently reading for review a book called The Quantum Divide, which is about half way between a popular science book and a student text, and which takes some offence at the way this quantum strangeness is often portrayed. What popular science books frequently say, and I think I have been guilty of this, is that a particle goes through both slits (i.e. is in more than one place at a time) and interferes with itself. Gerry and Bruno (I'm not being overly familiar, these are surnames), the authors of the book, take serious umbrage at this wording:

And just to be clear why they are having to make this distinction:We hasten to emphasize that quantum mechanics does not actually say that an electron can be in two places at once, hence the use of the proviso that quantum mechanics only superficially appears to allow the electron to be in two places at once.

Quantum theory does not predict that an object can be in two or more places at once. The false notion to the contrary often appears in the popular press, but is due to a naïve interpretation of quantum mechanics.(Their emphasis in both cases.) In one way I am very grateful to G&B as I will be more careful with my wording as a result of this. But on the other hand, I think this typifies how scientists trying to present science to the general public can get a bad press. They no doubt think what they are doing is emphasizing their precision, but this comes across as the worst kind of academic bitching. More seriously, I think G&B are in danger of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. All descriptive models of something as counter-intuitive as quantum theory are inevitably approximations - what they are really doing here is not liking someone else's language, even though it gets the basic point across better than their version in some ways.

The idea that, say, a photon goes through both slits and interferes with itself is technically inaccurate. The photon is not in any place with certainty, but is only described by the wave equation, which gives it a probability of being located in each slit. And the interference is of that probability wave, not the photon itself. However it is arguable that the probability wave is the photon - that it is the only meaningful description of the photon and as such if we say that the probability wave has values at both slits and interferes with itself, we are surely not stretching things too far to replace the clumsy 'the probability wave' with 'the photon'.

Okay, it's not perfectly accurate, and we certainly should explain what we are doing and probably often fail to do so. But I don't think this is any more a problem than when physicists speak of the big bang or dark matter as if it they are facts, rather than our current best accepted theories. To make a big thing of it as G&B do is, frankly, to miss the point.

Published on February 22, 2013 01:35

February 21, 2013

When the remake is better

We see a steady stream of TV programmes from the UK crossing the Atlantic and being remade for a US audience. Often the result is to water down the original, or to lose the point of the show. I would be hard pressed to think of a remake done this way that was better than the original... until now.

We see a steady stream of TV programmes from the UK crossing the Atlantic and being remade for a US audience. Often the result is to water down the original, or to lose the point of the show. I would be hard pressed to think of a remake done this way that was better than the original... until now.I was a great fan of the Michael Dobbs 1990 TV drama and books House of Cards with its scheming chief whip (and, eventually, Prime Minister) Francis Urquhart. Everything about it was superb. Ian Richardson made a brilliant Machiavellian villain, and the show was groundbreaking in its use of direct access to the camera, with Richardson making asides to the audience and giving us wonderful knowing looks. And, of course there was that catchphrase 'You might very well think that; I couldn't possibly comment.'

Now Netflix has remade the programme from the original shortish series to a 13 part epic starring Kevin Spacey. And it is excellent. Although the original was great, this is genuinely better. It's more sophisticated, more complex and brilliantly done. Spacey, as Francis Underwood (presumably Urquhart was too difficult a name) has that same ruthless charm and uses the camera aside to great effect.

I've had Netflix for a while now, and am very impressed with it, but never expected they would produce their own drama of this quality - well done guys.

There is only one slight problem with the storyline, which will involve a spoiler, so I will briefly discuss that further down the page - otherwise this piece is finished.

Image from Wikipedia

±

|

|

|

|

|

S

P

O

I

L

E

R

A

L

E

R

T

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

±

One of the most interesting aspects of the new series was how it would end. The original book had Urquhart commit suicide at the end, when the house of cards collapses. But in the TV show he throws the reporter off the tower of Westminster Palace, gets away with it and goes on to become Prime Minister. (Hence the two subsequent novels are follow ups to the TV show, rather than the first novel.) The Netflix series does neither, but ends unresolved just before the house of cards collapses. Arggh! Nasty people. Hopefully that means there will be a sequel.

Published on February 21, 2013 01:53