Brian Clegg's Blog, page 121

April 18, 2013

Real men don't use tablets

Yesterday I spent an enjoyable day in London, with an interview at the Guardian newspaper in the morning and giving a talk at Westminster School (thankfully well after the Thatcher funeral was our of the way) in the evening. In between I had a few hours to spare, so equipped with the mobile office that is my iPad and a few books I decamped to the RSA House in John Adam Street which has a pleasant library (with free wi-fi) for us privileged Fellows to work in.

Yesterday I spent an enjoyable day in London, with an interview at the Guardian newspaper in the morning and giving a talk at Westminster School (thankfully well after the Thatcher funeral was our of the way) in the evening. In between I had a few hours to spare, so equipped with the mobile office that is my iPad and a few books I decamped to the RSA House in John Adam Street which has a pleasant library (with free wi-fi) for us privileged Fellows to work in.So there I am in a largish room with quite a few of us working at tables, mostly on laptops, a couple using the traditional (and rather clunky looking) PCs provided and two of us on iPads.

Taking a look at this scene, I wonder if I see the reason why the iPad, despite its obvious superiority for many mobile tasks, has not conquered the macho business world quite as quickly as it should have. Because even though I can type almost as quickly on the iPad screen as a traditional keyboard, the curious hovering way your hands move over a touchscreen look remarkably... camp. I really can't think of a better word to describe it. Comparing my fellow iPad user's gestures with those on a butch laptop, it just wasn't the same. Your fingers flutter in a way that is very different from a conventional computer.

Don't get me wrong - tablets are making big inroads in business, and will continue to do so, but I do wonder if this effect has slowed down their uptake.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on April 18, 2013 01:52

April 17, 2013

News and bombings

Apologies for having two news media posts in the same week (and I write this on my phone on the way to Grauniad Towers to record a podcast interview) - it's events, dear boy, events.

I was struck by a letter in today's i newspaper moaning about the heavier coverage of the Boston bombings than those in Iraq. 'Are American lives so much more newsworthy than Iraqis?' asks the writer. The simple answer is yes, for two reasons. (Note this is newsworthy, not valuable, a totally different question.)

Firstly it's a matter of the nature of news. The unusual is more newsworthy than the usual. 'Sun does not rise,' would make a better news story than 'Sun rises.' Bombings are relatively rare in the US.

Then there's the matter of closeness. A death in your family is more newsworthy than a death in the UK, which itself is more newsworthy than a death in a remote part of the world. Forget the global village, that's the way it is. And like it or not a bomb in Europe or America is culturally closer to most in the UK than one in Iraq or China.

To expect otherwise is simply naive.

I was struck by a letter in today's i newspaper moaning about the heavier coverage of the Boston bombings than those in Iraq. 'Are American lives so much more newsworthy than Iraqis?' asks the writer. The simple answer is yes, for two reasons. (Note this is newsworthy, not valuable, a totally different question.)

Firstly it's a matter of the nature of news. The unusual is more newsworthy than the usual. 'Sun does not rise,' would make a better news story than 'Sun rises.' Bombings are relatively rare in the US.

Then there's the matter of closeness. A death in your family is more newsworthy than a death in the UK, which itself is more newsworthy than a death in a remote part of the world. Forget the global village, that's the way it is. And like it or not a bomb in Europe or America is culturally closer to most in the UK than one in Iraq or China.

To expect otherwise is simply naive.

Published on April 17, 2013 01:30

April 16, 2013

You got it wrong, BBC

Unlike some, I am a great fan of the BBC. I naturally think nice things about them. I think they do great work and are a national treasure. Some of my favourite programmes are from the BBC, and I don't resent paying the licence fee. But they got it horribly wrong over the recent North Korea documentary scandal.

Unlike some, I am a great fan of the BBC. I naturally think nice things about them. I think they do great work and are a national treasure. Some of my favourite programmes are from the BBC, and I don't resent paying the licence fee. But they got it horribly wrong over the recent North Korea documentary scandal.In case you haven't heard/are looking at this through the mists of time when the incident is long forgotten, the BBC sent an undercover team along with a student visit to North Korea arranged by the LSE. The university and many academic bodies are protesting that the broadcaster put the students at risk, and undermined the ability of academics to be considered neutral, safe people to have working in dangerous areas.

Two things strike me about this. One is a very small one, but curious. I have heard at least ten reports on this on the BBC news, and not one of them has mentioned a very pertinent fact that was in the Independent on Sunday. It seems that one of the LSE academics leading the trip was the wife of the BBC reporter John Sweeney at the heart of the furore, and he was travelling as her husband. This doesn't have any bearing on whether or not the BBC was right or wrong to do this, but it seems very strange that it has not been mentioned.

The main one, though, is why I think the BBC did get it wrong. My knee-jerk reaction was to side with the BBC against the LSE, an organization that usually gets my back up, especially when its spokesperson sounded like an archetypal plummy over-priveleged whining academic. After all, the BBC needs to be able to do investigative journalism, and this was a rare opportunity to get into this secretive country. But when I actually thought about it from the viewpoint of the students, I realized just how wrong this whole thing was.

The BBC's defence was that the students were all adults (18 or over), they had been warned there would be a journalist with them, and about the accompanying risk in advance, and they had been told there were actually three journalists with them when the were in Beijing on the way to North Korea. What they have not said, though, is what choice the students were given.

Thinking back to my 'adult' student days, it would not have been an easy position. Okay, we didn't have physics field trips, but I assume from the students' viewpoint, this trip was a contributory part of their course. If they said they wouldn't go, presumably it could have a negative influence on their degree, or whatever they were studying for. Seen in that light it was totally wrong to say that the students were given a clear choice, if, as I suspect, the choice given to them was either go or don't go. The only honourable choice the BBC could have offered them was 'If anyone is uncomfortable with this, the BBC will not go with you, the trip will simply go ahead as originally planned.' To expect students to weigh up the risk of having BBC personnel along against the risk of damaging their qualifications was too high a price to pay.

As soon as you look at this from the students' viewpoint, it is clear that the BBC got it wrong.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on April 16, 2013 00:48

April 15, 2013

Periodic puzzle

I'm drinking my coffee from this mug todayLast night's episode of Endeavour, the prequel to Inspector Morse, in which we see a young Detective Constable Morse learning his trade, featured one of those fiendishly complex puzzle-based clues that I am sure real-world detectives never come across (but are still fun for the viewer).

I'm drinking my coffee from this mug todayLast night's episode of Endeavour, the prequel to Inspector Morse, in which we see a young Detective Constable Morse learning his trade, featured one of those fiendishly complex puzzle-based clues that I am sure real-world detectives never come across (but are still fun for the viewer).Morse spotted that the set of hymn numbers on a hymn board in a church (which we had earlier seen the soon-to-be-murdered vicar putting up) were strange. The numbers were 74, 17, 18, 19. I was slightly pleased with myself to spot that this was an unusual collection of numbers and probably meant something, but kicked myself for not spotting the clues the writer had carefully provided us for doing the decoding.

We knew that the vicar loved puzzles, had been a cryptographer during the war, and previously had been a chemist - there was even a framed periodic table on the wall of his house.

What Morse spotted, but I kicked myself for not doing, was that if you write out the chemical symbols of the elements with the atomic numbers the vicar put up on the board you get:

W ClArK

And low and behold, the murderer was one W. Clark Esq. Clever, eh?

What struck me since is that I could not do the same for myself. I could do a rather mangled B ClErGe, which might give you a clue, but without an E or a G, it's a bit of a mess. And that led me on to wonder just what the people who devised the chemical symbols were smoking (or inhaling in their fume cupboards).

It all starts well with a simple rule that seems to be 'use a single letter for the first instance and a two letter variant for subsequent ones.' So in the first couple of rows of the table we get the single letters H, B, C, N, O and F, with He and Be for the next instances. But why is lithium, the first L, Li instead of L? Why is magnesium, the first M, Mg instead of M? You might assume that they decided not to use any more single letter names. Only we later come across P, S, K, V, Y, I (not even the first I) and W.

It's totally bonkers.

Published on April 15, 2013 01:51

April 12, 2013

Chinese boffins should know better

Ceci n'est pas une superordinateurI generally rather enjoy the slightly anarchic view of technology news provided by website

The Register

, but I have to confess that one of their recent articles got my dander up, though to be fair to El Reg, more because of what I presume was in a Chinese press release than because of the way it was reported.

Ceci n'est pas une superordinateurI generally rather enjoy the slightly anarchic view of technology news provided by website

The Register

, but I have to confess that one of their recent articles got my dander up, though to be fair to El Reg, more because of what I presume was in a Chinese press release than because of the way it was reported.'Chinese boffins predict iPad-sized supercomputers' screams the headline. Now, I ought to point out for those not familiar with it that The Register has a house style of using ironic labels, so Apple lovers are usually 'fanbois', iPads are usually (though not here) 'fondle slabs' and scientists are always 'boffins'. But what I dislike here is the use of tenuous leap from an interesting bit of science to a vapourconcept (if I can generate my own Regism).

What the Chinese scientists have done is observe the quantum anomalous Hall effect (yes, as

So basically what we have is a first demonstration of a hard to produce effect, in a lab, in conditions that couldn't possibly be duplicated in mass production without radical changes that may well stop the effect working. Yes it is just possible that it might result in faster computers... but it may well not. And the idea of an iPad-sized supercomputer being the outcome is a bit like saying 'We have now built Voyager 1, which due to special relativity has travelled 1.1 seconds in the future. This technology may mean we will be able to build Back to the Future style time machines.' Okay, it's possible, but it's a big leap.

According to the article, team leader Xue Qikun is quoted as saying 'The technology may even bring about a supercomputer in the shape of an iPad.' Mostly scientists are getting the idea that making predictions for the technology that could be produced from their science based on extreme extrapolation is simply a mistake that results in reduced public trust in scientific pronouncements. But clearly some have still to learn.

You can read the Register article here and see the paper (if you subscribe to Science) here.

Published on April 12, 2013 00:39

April 11, 2013

A dose of salts

In need of a dose of salts? At one time, the obvious thing to do would be take yourself off to Epsom. But magnesium sulfate, the compound behind those foul tasting waters, really could have health benefits when added to your bath - and it's the subject of my latest podcast for the Royal Society of Chemistry.

In need of a dose of salts? At one time, the obvious thing to do would be take yourself off to Epsom. But magnesium sulfate, the compound behind those foul tasting waters, really could have health benefits when added to your bath - and it's the subject of my latest podcast for the Royal Society of Chemistry.Hurry along to the RSC compounds site to see why bath salts shouldn't just be for granny and much more about Epsom's most famous product - or if you've five minutes to spare now, click to to have a listen to my podcast on magnesium sulfate.

Published on April 11, 2013 00:00

April 10, 2013

The naming of names

I gather from the BBC that Peter Higgs gets rather irritated when the Higgs boson gets referred to as the God particle. Leaving aside those who get miffed that Higgs himself gets the sole glory of the name, I think this is very short-sighted.

I gather from the BBC that Peter Higgs gets rather irritated when the Higgs boson gets referred to as the God particle. Leaving aside those who get miffed that Higgs himself gets the sole glory of the name, I think this is very short-sighted.Dr Higgs' objections are twofold: a) that he is an atheist and b) 'I know that that name was a kind of joke. And not a very good one I think.' To be honest, I think it might better if we had more God particles and less of the kind of names scientists tend to come up with left to their own devices.

Let's get those objections out of the way first. So what if he is an atheist? Does that make the word 'god' disappear? Irrelevant. (And 'god' is used illustratively by plenty of atheists and near-atheists - Einstein and Steven Hawking to name but two.) As for the second, well yes, it was a sort of joke. But what's the problem with that? A touch of taking-self-too-seriously perhaps? According to Leon Lederman, the Nobel Prize winning physicist behind the name when he wrote a book with that title, he really wanted to call it the 'goddamn' particle, but the publishers wouldn't let him. (To be fair, the publishers were probably correct. 'The God Particle' is attention-grabbing. I have a book called The God Effect , a direct reference to this name, and having the G word in the title of a book does no harm to it.) For that matter 'big bang' was a sort of a joke too, but though there were a few moans early on, it has generally been comfortably accepted.

The fact is, there are three kinds of scientific names. Probably the best are the simple ones that are catchy and get the point across. Think electron, positron and photon, for instance. These are the ideal, but they are few and far between. Then there are the occasional jokey but memorable ones. God particle and big bang apart, we have, for instance, those interesting proteins like sonic hedgehog, pokemon, seahorse seashell party, dickkopf, R2D2, Homer Simpson, glass bottomed boat and, my favourite, abstinence by mutual consent.

Unfortunately we also have lots of dross. Either words with no real mental handles that require rote learning and don't really put anything across (think boson, fermion, lepton etc.) or even worse convoluted terms that if anything mislead. Gauge theory would be a good example - it sounds like it's about measurement, but actually it is, of course, (to quote Wikipedia): a type of field theory in which the Lagrangian is invariant under a continuous group of local transformations. That makes it nice and obvious, doesn't it children?

I think when scientists moan about populist names some are in suffering from a problem that goes back to medieval times. I am very fond of the thirteenth century proto-scientist Roger Bacon and he was a great believer in communicating science. He had to be, bearing in mind the book proposal he first wrote was 600,000 words long. However he didn't believe knowledge should be shared with common oiks like you and me. He was very much of the 'pearls before swine/cabbages before goats' theory. Knowledge was only for the cognoscenti, and I think some scientists actually resent anything escaping from their ivory tower world.

The other reason some dislike these names is the feeling that they trivialize - but that misunderstands the whole point of making something memorable. Which is more likely to stick - big bang or gauge theory? Black hole or eigenvector? If you want to communicate, you have to think about the words you use, and all too often the words that are enshrined in science are a mess.

Published on April 10, 2013 01:13

April 9, 2013

Privatization worked

There will be much said positively and negatively about the late Margaret Thatcher over the next few days. But whatever your opinion of her policies and what they did for or to the country I have to say that, from the inside, the impact of privatization on at least one company was wonderful.

There will be much said positively and negatively about the late Margaret Thatcher over the next few days. But whatever your opinion of her policies and what they did for or to the country I have to say that, from the inside, the impact of privatization on at least one company was wonderful.I joined British Airways when it was a nationalised industry. It wasn't an unpleasant place to work - far from it - but, frankly, it was fairly low energy. I had an interesting job and I enjoyed it, but the overall feeling was of a company that had little unity and more interest in the status quo (down to the separate 'officers' mess' style management canteen) than, for instance, its customers. In the entire time I was working for a nationalized company I only saw a board member once, and that was in the run up to privitization.

Privatization changed everything. There was a dramatic new energy - it really felt like somewhere exciting to be working. More to the point, the majority of people working there went from being enthusiastic about planes or technology to being proud of working for British Airways. There was a dramatic new focus on customer service - suddenly, customers mattered to everyone. I got significantly more exposure to board members, apart from anything because they were spending considerable amounts of time with the staff, rather than squirrelled away in Buckingham Palace Road in London. Without any doubt whatsoever, the airline became a much better place to work, and provided a much better experience to the flying public. I honestly believe that this could never have happened without privatization.

I'm not saying it was perfect, and those who still work for the airline may well say it isn't now what it was back then. But those who look back at a golden age of nationalized companies are living in cloud cuckoo land. Privatization was right for BA - there is no doubt whatsoever in my mind.

If you are a supporter of Mrs Thatcher's work, don't take this as wholehearted praise. There were other things her government did that were disastrously handled or simply misguided. But if you are of the demonizing camp, frankly you do your intelligence a disservice. Everything the Thatcher government did was certainly not bad, as I can testify. Back then, you might well have had reason to see things through rosy tinted spectacles or coloured by the flames of hatred. But now we have the chance to employ 20:20 hindsight and should accept that both bad and good things came out of that period.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on April 09, 2013 00:48

April 8, 2013

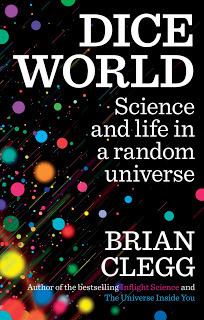

Mind bending shoes

One of the key points in my new book

Dice World

is something of a truism in the scientific world - and yet it's something that constantly trips people up (in the case of the example we've got here, literally). It's all to do with the way we interpret numbers - something that is crucial to science, but that we also do frequently in everyday life. And there we hit a problem. We interpret the world around us through patterns - and all too often we see patterns where they don't exist. If, for example two numbers move in a similar way (they are correlated) we tend to assume that there is a cause that links the two (causality). And its very easy to forget the scientists' mantra 'correlation is not causality.'

One of the key points in my new book

Dice World

is something of a truism in the scientific world - and yet it's something that constantly trips people up (in the case of the example we've got here, literally). It's all to do with the way we interpret numbers - something that is crucial to science, but that we also do frequently in everyday life. And there we hit a problem. We interpret the world around us through patterns - and all too often we see patterns where they don't exist. If, for example two numbers move in a similar way (they are correlated) we tend to assume that there is a cause that links the two (causality). And its very easy to forget the scientists' mantra 'correlation is not causality.'It isn’t just the person in the street who can confuse correlation with causality. In 2004 a Swedish scientist called Jarl Flensmark published an academic paper titled Is There an Association Between the Use of Heeled Footwear and Schizophrenia? What is disturbing is that despite apparently asking a question in the title of the paper, he presents the hypothesis in the text as if it were a statement of fact: ‘Heeled footwear began to be used more than 1,000 years ago and led to the occurrence of the first cases of schizophrenia.’ Flensmark then shows a parallel between the growth of heeled shoe production and an increase in the prevalence of the disease.

We are told that the first known examples of heeled shoes were in Mesopotamia, as were the first institutions for mental disorders. A whole string of European royals are listed as possible victims of schizophrenia and who were also known – or at the very least thought – to have worn heeled shoes. Flensmark notes that it is the upper classes around the world that typically wore heeled shoes first – and it is the upper classes who were more likely to report symptoms that would now make doctors suspect the existence of schizophrenia. The pattern, Flensmark suggests, is simple. After heeled shoes are introduced, the first cases of schizophrenia appear, and as wearing of the shoes grows more popular, so do the frequency of attacks of the disorder. Simple cause and effect.

Flensmark comes up with an ingenious, if rather intricate explanation for why walking in such shoes could have an influence on the brain. But there are so many opportunities here to confuse correlation and causality. Heeled shoes have, as he suggests, typically first been taken up by the upper classes, because they are impractical, and the appeal of impracticality usually only develops once you don’t have to worry about where your next mouthful is coming from. Wearing such shoes also will tend to increase as society as a whole gets wealthier and more sophisticated. Yet the trappings of class, wealth and sophistication are also more likely to result in more reporting of illness, mental or otherwise. If life is a constant struggle, you either die or you get on with existence despite any illness. In a primitive society like medieval Europe, there is no medical safety net. Being seriously ill and staying alive is a luxury only available to those who can afford it.

What seems to be recorded here are two separate causal links, which when combined result in an unrelated correlation. It seems entirely reasonable that wealth and being of a higher class cause the increased wearing of heeled shoes. And it also seems likely that wealth and being of a higher class produced increased reporting of the symptoms we associate with schizophrenia. But there is no reason to deduce that the shoes caused the mental illness. In fact if there were a causal link, the more obvious one might be that schizophrenia caused sufferers to be more likely to wear heeled shoes, which are hardly a rational piece of footwear. There are, no doubt, many other potential causal structures as well, but the point is that an academic has made an assertion of causality despite there being absolutely no real grounds for making it. Humans – even academics – need their patterns.

Whenever someone tells you on the news, or even in an academic paper, that A causes B, make sure they have clearly identified the causal link. Otherwise get yourself a significant pinch of salt.

Find out more about Dice World.

Published on April 08, 2013 00:54

April 5, 2013

Goths and hate crimes

You shouldn't be attacked for looking like this

You shouldn't be attacked for looking like this- or any other wayThere was a wonderfully cringe-making piece on the often glorious Channel 4 News last night, covering the move by Greater Manchester Police to consider attacks on goths, emos, bikers and goodness knows what cultural groupings as hate crimes, putting them on a par with racist attacks. The cringe-making part was Jon Snow saying he would like to dress like a Fearless Vampire Killers band member who was one of his interviewees - but the interesting point was made by a journalist present. He was doubtful about this move because it was making an artificial distinction - and I think he was spot on.

The thing is yobs (as the journalist labelled them (and, no, he wasn't from the Sun, it was a broadsheet)) will attack anyone for looking different. It all depends on context. No one is going to attack someone for dressing like a goth at an a concert for a band that has that particular look. But they might have trouble if they turned up in a suit and tie. When I was at school I was twice attacked for wearing my school uniform. Not just verbal abuse (there were plenty of examples of that) - once a punch to the jaw on a crowded railway station (no one took any notice) and once having stones thrown at me in a quiet suburban street

The fact is that literally anyone can be attacked for looking different. For their age, the way they dress, the way they look, the way they behave. For having red hair. This is as old as the hills. I'm not saying it is acceptable - of course it is to be abhorred and punished. But to single out particular groups as a 'hate crime', implying that somehow attacks on other people for exactly the same reason are less significant is a serious mistake and should be avoided at all cost.

Image from Wikipedia

Published on April 05, 2013 03:07