Justine Musk's Blog, page 19

October 11, 2012

the art of finding your calling

The potential of our own creativity is rapidly being compromised by the era we live in. I believe that genius in the 21st century will be attributed to people who are able to unplug from the constant state of reactionary workflow, reduce their amount of insecurity work, and allow their minds to solve the great challenges of our era. Brilliance is so rare because it is always obstructed, often by the very stuff that keeps us so busy. — Scott Belsky

1

I went to hear Gabrielle Bernstein and Mastin Kipp speak to a packed room of mostly women, mostly young. During the Q & A a dark-haired beauty stood up in the second row and asked: what do you do in the meantime when you’re still trying to find your Purpose? How do you find your Purpose?

(Yes, this is the kind of scene where people talk about ‘spirit’ and use the word purpose with a capital P. If you’re not into that vocab, I get it, but bear with me.)

She said she was doing the soul-searching and writing in her journal and taking action to explore different things and opening herself up to be receptive and letting things come to her. She said she was “praying on it”. But what should she do?

“Everything you’re already doing,” Gabby said instantly. “You answered your own question. You’re doing your spiritual practice – “ She snapped her fingers. “Deepen your spiritual practice! That’s your Purpose right now! See, spirit is speaking through me, from me to you, and now you know. That’s your Purpose.” She beamed.

I liked this answer. Maybe you don’t officially believe in god(dess)– I consider myself to be an atheist – but you can think of a spiritual practice as a creative practice. It’s when you carve out time each day to tap into the “internal guidance system” as Gabby put it: the enigmatic underside of your mind that doesn’t deal in words but sends up messages like flares: hunches, dreams, images, gut feelings, all forms of an intuitive and nonverbal intelligence that lives in your heart and stomach as well as your head.

2

In his book THE CLICK MOMENT, Frans Johannson has a chapter called “The Twilight of Logic”. In a world that’s changing so quickly – and when the speed of change itself is speeding up – planning for the future becomes problematic. The rules are too random. And the same logic that is apparent to you is also apparent to all the other guys, which means that everybody ends up doing the same things — which means that logic is no longer a competitive advantage.

If you have an English degree and you don’t know what to do with your life, it makes a lot of sense to go to law school. You can graduate along with everybody else who had the equally good sense to go to law school. You can then enter a job market so flooded with lawyers that now there aren’t enough jobs for them, let alone genuine career tracks.

As Johannson points out:

“Your chances of success actually drop when you analyze the market and try to predict what you need to succeed. Because logic led people to conclude that law school was a great way to become successful, law school became the exact opposite.”

So what’s the alternative?

Do something magical.

“There is really only one answer,” says Johannson, “it has to be an approach that is not logical, however strange that may sound.”

This is where the X factor comes in. Luck. Serendipity. The click moment: that moment of insight, that creative leap, that changes everything. When Diane Von Furstenberg thought up the wrap dress. When Apple came out with the iPod. When Stephenie Meyer dreamed into being the plot and characters of TWILIGHT.

Johannson talks in terms of big, career-defining, category-reinventing ‘click moments’, but what if a life can also be composed of small ‘click moments’ — one after another after another — that build on each other…and open up into something amazing?

How can you prepare yourself, in the course of daily life, to have those moments as often as possible?

3

Creativity builds on itself. It’s like links in a chain. Each link hooks off the other — off the other — off the other until you’ve made it to the opposite shore.

But you can’t get to that final link until you’ve progressed along all the ones preceding it.

It’s the unknowing that’s scary. I deal with this as a writer of fiction; I wrestle it to the ground (except when I don’t). No matter how extensively you outline, there is – at least for me – that sense of groping through the dark with barely enough light to see by. When the characters start talking, when the story starts lifting its head off the screen, I realize all over again that the world of an outline – a plan – is fixed and unchanging. The world of a story is not.

But even so, there’s enough light to see by.

And you can make the whole journey that way.

4

Creative intelligence is an intuitive intelligence. It speaks to you in a way that doesn’t seem logical at the time – that often seems to go against logic. You’ve got the chain in your hand but ahead of you it vanishes into darkness: where the hell is it leading you?

If creativity, as Steve Jobs so famously said, is a matter of connecting the dots, then the logic of those connections can only appear after the fact. That’s when it seems both obvious and inevitable. But before they connect, they’re just a bunch of random dots — and everybody else cocks their head at you and wonders what you’re doing. You wonder what you’re doing.

Gabby Bernstein made this point when she told the young woman (and the audience) why logic alone isn’t enough to find your Purpose. She offered Mastin and herself as examples: as “inspirational motivational type humans,” as Mastin referred to them, they are bestselling authors and A-list bloggers, they speak at sold-out events, they have followings that number in the hundreds of thousands.

“But our career paths made no sense,” Gabby stressed. “There’s no way we could have planned it all out in our heads. We could only do it by doing.” They moved forward action by action, link by link, responding to the moment, leaning into what worked and felt right, building on what came before. They were learning deeply and developing mastery — and they were also improvising. No matter how it might have looked to others, they had direction. Each day, they were tapping into their intuitive intelligence.

They didn’t know where it was leading them, but they managed to keep the faith.

In her book IMPROV WISDOM, Patricia Ryan Madson talks about creativity as a process of surrender rather than control. She invokes Eastern notions of art in which

“the artist is considered the servant of the muses, not their master. The artist shows up, practices carefully the strokes or steps, and then humbly takes his place as channel, as shepherd for the images to be brought forth. Ideas, songs, poems, paintings come through the individual but are not thought to be of him.”

Which is why a central maxim of improv is Don’t prepare

“…which really means to let go of our ego involvement in the process. When we give up the struggle to show off our talent, a natural wisdom can emerge…All of our past experience, all that we have ever known, prepares us for this moment.”

Which is another way of saying:

A big part of the battle is just showing up.

Day after day after day.

As, you know, a practice.

4

When you decide that your purpose is finding your purpose, you set your intention. And that thing is powerful. It directs the focus of your undermind, which co-creates your reality according to what it decides to bring to your conscious attention — and what to ignore.

When you carve out time each day to do some kind of creative practice, something that slows the chatter of the conscious mind and downshifts you into those relaxed, creative brain waves, you are creating the conditions that enable your purpose (of finding your purpose).

You open the door for your purpose to enter.

You show up.

And it’s possible that your Purpose will arrive in a flash of blinding revelation – cue the music of angels, or a really transcendent house DJ – but I think that’s rare.

I think your Purpose builds on itself over time.

It’s the voice in your head, sometimes so soft it’s easy to shunt aside, but keeps nagging you to Write that email. Read that book. Go to that seminar. Check out volunteer opportunities at that nonprofit. Go on that trip. Call that friend.

It’s that heightened attunement to the messages your own unconscious sends you by signaling out details in your environment that seem to relate to your inner life in an uncanny way. They must be carrying secret messages for you – and they are. (Otherwise known as synchronicity.)

Each action you take opens up into another action. Each action causes new things to happen that alters your environment in some way and gives you something new to work with or respond to.

No matter how lost you think you are, that inner sense of guidance is the chain you can grab to get to the other side. There might be just barely enough light to see by. But it’s enough. That’s the thing. It’s enough.

the art of finding your purpose (or your Purpose)

The potential of our own creativity is rapidly being compromised by the era we live in. I believe that genius in the 21st century will be attributed to people who are able to unplug from the constant state of reactionary workflow, reduce their amount of insecurity work, and allow their minds to solve the great challenges of our era. Brilliance is so rare because it is always obstructed, often by the very stuff that keeps us so busy. — Scott Belsky

1

I went to hear Gabrielle Bernstein and Mastin Kipp speak to a packed room of mostly women, mostly young. During the Q & A a dark-haired beauty stood up in the second row and asked: what do you do in the meantime when you’re still trying to find your Purpose? How do you find your Purpose?

(Yes, this is the kind of scene where people talk about ‘spirit’ and use the word purpose with a capital P. If you’re not into that vocab, I get it, but bear with me.)

She said she was doing the soul-searching and writing in her journal and taking action to explore different things and opening herself up to be receptive and letting things come to her. She said she was “praying on it”. But what should she do?

“Everything you’re already doing,” Gabby said instantly. “You answered your own question. You’re doing your spiritual practice – “ She snapped her fingers. “Deepen your spiritual practice! That’s your Purpose right now! See, spirit is speaking through me, from me to you, and now you know. That’s your Purpose.” She beamed.

I liked this answer. Maybe you don’t officially believe in god(dess)– I consider myself to be an atheist – but you can think of a spiritual practice as a creative practice. It’s when you carve out time each day to tap into the “internal guidance system” as Gabby put it: the enigmatic underside of your mind that doesn’t deal in words but sends up messages like flares: hunches, dreams, images, gut feelings, all forms of an intuitive and nonverbal intelligence that lives in your heart and stomach as well as your head.

2

In his book THE CLICK MOMENT, Frans Johannson has a chapter called “The Twilight of Logic”. In a world that’s changing so quickly – and when the speed of change itself is speeding up – planning for the future becomes problematic. The rules are too random. And the same ‘logic’ that is apparent to you is also apparent to all the other guys, which means that everybody ends up doing the same things — which means that logic is no longer a competitive advantage.

If you have an English degree and you don’t know what to do with your life, it makes a lot of sense to go to law school. You can graduate along with everybody else who had the equally good sense to go to law school. You can then enter a job market so flooded with lawyers that now there aren’t enough jobs for them, let alone genuine career tracks.

As Johannson points out:

“Your chances of success actually drop when you analyze the market and try to predict what you need to succeed. Because logic led people to conclude that law school was a great way to become successful, law school became the exact opposite.”

So what’s the alternative?

Do something magical.

“There is really one one answer,” says Johannson, “it has to be an approach that is not logical, however strange that may sound.”

This is where the X factor comes in. Luck. Serendipity. The click moment: that moment of insight, that creative leap, that changes everything. When Diane Von Furstenberg thought up the wrap dress. When Apple came out with the iPod. When Stephenie Meyer dreamed into being the plot and characters of TWILIGHT.

Johannson talks in terms of big, career-defining, category-reinventing ‘click moments’, but what if a life can also be composed of small ‘click moments’ — one after another after another — that build on each other…and open up into something amazing?

How can you prepare yourself, in the course of daily life, to have those moments as often as possible?

3

Creativity builds on itself. It’s like links in a chain. Each link hooks off the other — off the other — off the other until you’ve made it to the opposite shore.

But you can’t get to that final link until you’ve progressed through all the ones preceding it.

It’s the unknowing that’s scary. I deal with this as a writer of fiction; I wrestle this beast to the ground (except when I don’t). No matter how extensively you outline, there is – at least for me – that sense of groping through the dark with barely enough light to see by. When the characters start talking, when the story starts lifting its head off the screen, I realize all over again that an outline – a plan – is fixed and unchanging. The story, however, is not.

But even so, there’s enough light to see by.

And you can make the whole journey that way.

4

Creative intelligence is an intuitive intelligence. It speaks to you in a way that doesn’t seem logical at the time – that often seems to go against logic. You’ve got the chain in your hand but ahead of you it vanishes into darkness: where the hell is it leading you?

If creativity, as Steve Jobs so famously said, is a matter of connecting the dots, then the logic of those connections can only appear after the fact. That’s when it seems both obvious and inevitable. But before they connect, they’re just a bunch of random dots — and everybody else cocks their head at you and wonders what you’re doing, wandering around and collecting them. You wonder what you’re doing.

Gabby Bernstein made this point when she told the young woman (and the audience) why logic alone isn’t enough to find your Purpose. She offered Mastin and herself as examples: as “inspirational motivational type humans,” as Mastin referred to them, they are bestselling authors and A-list bloggers, they speak at sold-out events, they have followings that number in the hundreds of thousands.

“But our career paths made no sense,” Gabby stressed. “There’s no way we could have planned it all out in our heads. We could only do it by doing.” They moved forward action by action, link by link, responding to the moment and building on what came before. They were learning deeply and developing mastery — and they were also improvising. No matter what it might have looked to others, they did have direction. Each day, they were tapping into their intuitive intelligence.

They didn’t know where it was leading them, but they managed to keep the faith.

In her book IMPROV WISDOM, Patricia Ryan Madson talks about creativity as a process of surrender rather than control. She invokes Eastern notions of art in which

“the artist is considered the servant of the muses, not their master. The artist shows up, practices carefully the strokes or steps, and then humbly takes his place as channel, as shepherd for the images to be brought forth. Ideas, songs, poems, paintings come through the individual but are not thought to be of him.”

Which is why a central maxim of improve is Don’t prepare

“…which really means to let go of our ego involvement in the process. When we give up the struggle to show off our talent, a natural wisdom can emerge…All of our past experience, all that we have ever known, prepares us for this moment.”

Which is another way of saying:

A big part of the battle is just showing up.

Day after day after day.

As, you know, a practice.

4

When you decide that your purpose is finding your purpose, you set the intention. And those things are powerful. They direct your focus, which brings your own private reality into being according to what it decides to bring to your attention — and to ignore.

When you carve out time each day to do some kind of creative practice, something that slows the chatter of the conscious mind and downshifts you into those relaxed, creative brain waves, you are creating the conditions that enable your purpose (of finding your purpose).

You open the door for your purpose to enter.

You show up.

And it’s possible that your Purpose will arrive in a flash of blinding revelation – cue the music of angels in the background, or a really transcendent house DJ – but I think that’s rare.

I think your Purpose builds on itself over time.

It’s the voice in your head, sometimes so soft it’s easy to shunt aside, but keeps nagging you to Write that email. Read that book. Go to that seminar. Check out volunteer opportunities at that nonprofit. Go on that trip. Call that friend.

It’s that heightened attunement to the messages your own unconscious sends you by signaling out details in your environment that seem to relate to each other and your own inner life in an uncanny way. They must be carrying secret messages for you – and they are. (Otherwise known as synchronicity.)

Each action you take opens up into another action. Each action causes new things to happen that alters your environment in some way and gives you something new to work with or respond to.

No matter how lost you think you are, that inner sense of guidance is the chain you can grab to get to the other side. There might be barely enough light to see by. But it’s enough. That’s the thing. It’s enough.

October 4, 2012

four things you should know about your calling

If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you; if you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you. — Gnostic Gospel of Thomas

What you fear is an indication of what you seek. — Thomas Merton

1. You don’t get to choose your calling.

I guess that’s why it’s called “a calling”. We can’t choose what calls us; we can only listen close – and have the courage to accept what it tells us.

Callings can be so damn inconvenient.

They usually arrive as some form of pain.

They’re an itch, a yearning, a slow deadening of the soul, a restless knowledge that you are meant for something else, if you can only figure out what it is.

The body knows. Finding your calling can be like that child’s game of hot and cold. When you’re moving away from your calling, the body treats that as – cold! — nothing less than self-betrayal. What you fail to bring forth can destroy you. The body finds some way to break down. You get sick. You get depressed. You get sick and depressed.

As you move toward your calling – hot! — you get glimmers of something else entirely. A sense of flow and absorption. A flash of joy. A growing excitement.

My sister once came to a major life crossroads: renew her contract with her current employer or strike out into the unknown territory of new opportunities — and a stretch of unemployment.

She chose to renew her contract because she thought it was the “responsible” thing to do.

The morning after she made that decision, she literally could not get out of bed.

She stayed in bed for four days.

She took that as a sign to reverse her decision.

She’s much happier now. (And on a different career track in a different city.)

2. You can only live out your own calling.

Your calling is your soulprint: like a fingerprint, it is intricate and complex and unique to you. You’re born with it inside you. No one else can give it to you, although some might try — starting with your parents.

Jung once said: The greatest burden a child must bear is the unlived life of the parents.

As we grow up, we learn how to please, and we assemble our ‘false self’ accordingly: that collection of ideas and notions and ‘shoulds’: what we should be and how we should act and the goals we should pursue in the world.

To get at the truth of your calling, you have to crack open that false self and see what lies within.

You have to recognize the aspects of your life that don’t rightly belong to you, and as a result are weighing you down. You have to take that alien weight and give it back to its proper owner:

This is yours. I am done with it. I refuse to carry it any longer.

3. Your gifts point the way to your calling.

The problem with your gifts is that they generally need to be recognized as gifts by somebody other than you, usually as early as your childhood. Someone else needs to see what lights you up, what comes so easily to you that you will grow up taking it completely for granted, thinking that everybody else can do that. Guess what? They can’t.

I remember online biz wunderkind Laura Roeder talking about how she’d taken an online strengths test that identified her primary strength as ‘focus’.

“At first I thought that was really stupid,” she said (I am paraphrasing here). “I thought, everybody can do that. What’s so special about that?”

(Listening to her, I remember feeling envy, because ‘focus’ is not one of my strengths. If anything, I’ve been able to decipher my calling because of how certain activities call forth a focus so intense and consuming I lose time. But in the rest of my life, I have ADD. Literally. I take medication for it.)

When those gifts are mirrored back to you, you can identify them — and nurture them. You can put yourself on the road to true mastery. You can own your gifts. You can own the crap out of them.

You can commit yourself full-out. You can unify your life around the practice of your talent and see what kind of greatness becomes possible for you.

But you have to have faith in your gift.

As Stephen Cope points out in his THE GREAT WORK OF YOUR LIFE: your gift – which he refers to as The Gift – is indestructible. It’s permanent. It doesn’t disappear because you neglected it for forty years — which means it’s never too late to circle back to what you might have missed before. It lives near the center of you.

But your faith in your gift (The Gift) is something else entirely. Your faith can be tender and fragile and susceptible to doubt.

Doubt, by the way – and a flashbulb popped off in my head when I learned this – means, at least in terms of your calling, being stuck. It’s “a thought that touches both sides of a dilemma at the same time.”

It paralyzes you.

It splits you down the middle and pins you to the floor, unable to take action. Some of us stay there so long, and get so comfortable there, that we don’t realize we’re in doubt at all: we think that life is supposed to feel like this.

4. Your calling is where your gift intersects with the times.

Our calling is where The Gift that’s inside us from birth connects with the world we’re born into. It’s our responsibility to develop The Gift in the way it’s called forth — to serve the world. Not just ourselves. The freaking world.

“The Gift”, writes Cope, taking these ideas from the Bhagavad Gita, “cannot reach maturity until it is used in the service of a greater good. In order to ignite the full ardency of [your calling], The Gift must be put in the service of The Times.”

(You could think of The Gift as your ultimate value proposition, your unique point of awesomeness, the thing that meets a need in a way that sets you apart.)

Here’s the thing:

Your life belongs to the world.

And although the creative process of whatever it is that you do, belongs to you, the final outcome – the fruit of that labor – is not yours. It is beyond you. It belongs to the world.

You let go and let be.

(Which gives you greater peace of mind, by the way, which allows you to engage more fully with your process, which puts you in deeper flow, which makes you greater at what you do.)

Otherwise you live a life trapped in self. You take your self as your main mission in life, and this causes suffering – because it isolates you, because the self isn’t big enough for your real yearnings and abilities, because, as Martin Seligman put it, “the self is a poor site for meaning.”

Cope writes:

“If you don’t find your work in the world and throw yourself wholeheartedly into it, you will inevitably make yourself your work….You will, in the very best case, dedicate your life to the perfection of your self. To the perfection of your health, intelligence, beauty, home, or even spiritual prowess. And the problem is simply this: This self-dedication is too small a work. It inevitably becomes a prison.”

Your self will never be enough. Perfection forever eludes you. You must deal with your aging body, your aging mind, your fading beauty. Even your children will grow up and leave you.

So you look to the world.

When you understand that you are the world – when you see the world as your self, and your self as the world – “ you can care for all things.” You can live beyond yourself – which also means you can live with purpose, awe and meaning.

You play your essential part in a much bigger picture. You know how and where you belong.

“Our actions in expression of [our calling] – my actions, your actions, everyone’s actions – are infinitely important. They connect us to the soul of the world. They create the world. Small as they may appear, they have the power to uphold the essential inner order of the world.”

In other words, it isn’t selfish – or trivial – or a luxury – to pursue your calling, wherever it might lead you: it’s a sacred obligation. Because, in the end, it isn’t just for you. It’s for what you can give the world. It’s how you can be of true service.

When we’re fully engaged, when we’re expressing our gifts, when we’re living a deep sense of mission, when we’re contributing, when we’re being our full-out selves –

That way lies happiness.

What you bring forth can save you.

And if it can save you, it can also save the world.

September 29, 2012

fate, ripped abs + the lie behind self-improvement

My friend and trainer told me a story from when he was living and dating in New York City.

He was working as a male model and acting in commercials. He didn’t like telling strangers this when they asked the “what do you do?” question because he found the consequent conversation (“Have I seen you in anything?”) awkward and tedious. (“Well, I was in a New York Times commercial…I was the guy reading the sports section….”)

So when women asked him what he did, he told them, “I’m a dentist.”

“Oh,” they would say, and drop the subject.

One night he hit it off with a French ballerina passing through town. They went back to his place. They got really, really friendly. She ripped open his shirt, saw his ripped abs, and said in her thick French accent, “You’re no dentist!”

And he had to admit that he wasn’t.

I like this story partly because I like what it says about identity, how it’s written right into your body. We often say, in this culture of obsessive self-improvement, “You can be anybody you want to be” – but I don’t think that’s true.

In his book FATE AND DESTINY, Michael Meade defines ‘fate’ as the cross-section of genetics, environment and events that shapes our possibilities. We are born into a very particular set of limitations and gifts. If we accept our limitations (“I am scattered and disorganized”) and discover and develop our gifts (“I am highly creative”), we can come to a strongly grounded sense of who we’re meant to be and what we’re meant to do in this lifetime. But it’s not a matter of becoming anybody you want to be – because you can only become more (or less) of what you already are.

It’s more a matter of, as Hugh MacLeod likes to say, remembering who you are. And a big part of that is remembering who you are not.

You’re no dentist.

Remembering is necessary because You can be anybody you want to be has a way of turning into You can be who you’re supposed to be. It’s the box that you’re supposed to fit into. You’re a girl – or a boy – so you’re supposed to be and act a certain way. You’re a member of this family or that culture so you’re supposed to behave and believe and choose your goals accordingly.

You can be anybody you want to be has a way of turning into You can be anybody that they want you to be.

And you can’t.

(Sorry.)

But when you rip open that shirt to find the ripped abs of truth – when you remember who you are – the question then becomes: Do you declare yourself?

Or do you keep yourself in hiding to avoid uncomfortable conversations?

Problem is when we role-play, we start to believe what we thought we were only pretending.

The truth of who we are slips away. We forget ourselves all over again.

Say it enough times and you might start to think that you are, in fact, a dentist. Until life finds some way to force you to know otherwise.

September 25, 2012

the art of being original ( + the best thing you’ve got going)

“There’s an African proverb: ‘When death finds you, may it find you alive.’ Alive means living your own damn life, not the life that your parents wanted, or the life some cultural group or political party wanted, but the life that your own soul wants to live. That’s the way to evaluate whether you are an authentic person or not.”

— Michael Meade

“The best thing you’ve got going for you,” she told me, “is your originality.”

She said, “It’s like there are two sides to you. There’s the perverse, bold, rebellious side. That’s the side that gets pissed off. That’s the side that questions everything.

“And then there’s the conventional side, that wants to hunker down and keep safe, fit in. It gets scared and uneasy about what your other side compels you to do.”

She said, “It won’t be your conventional side that makes you successful.”

She said, “You can’t live a conventional life because you’re no good at it and it doesn’t make you whole.”

It’s like we have two lives inside us: the life we’re supposed to live, and the life of the soul.

We learn to navigate the world around us, the expectations of others, we accommodate and compromise until something happens and it all breaks down. We hit a crisis point.

The life of the soul sends up a flare: hey, I’m dying here, pay attention.

The old strategies don’t work anymore. The compromises you made between the outer life and the inner life start to feel like a deal with the devil.

And we have ourselves an identity crisis.

At the time, it feels like hell. There’s loss involved: something was taken from you. Or maybe you’re forced to let it go. Or maybe it never belonged to you in the first place and you finally have to accept that.

The life of the soul demands these acts of truth.

We talk so much about being authentic; we talk less about what that actually means. Just be yourself, we say – but if it was that easy, we wouldn’t have to say it, and we wouldn’t find authenticity so remarkable that we’re constantly remarking on it.

To be original is to go against everything we learned in childhood. We were punished when we stepped outside the lines, and if our parents didn’t do it, we did it to each other. We beat each other into the right kind of manhood. We shamed each other into proper girlhood.

We learned to be unique and special so long as we’re like everybody else.

That urge to be safe – from the shaming, the beating – is so strong we’ll sell our souls for it. But when we do that, what’s left? Things keep breaking down. Life becomes a series of crisis points. We get expert at ways to numb out.

The only thing we have, in the end, is our originality. We need to honor it.

The rest is a sham.

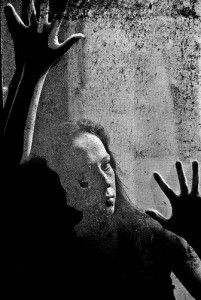

photo credit: Rubin 110 via photopin cc

the best thing you’ve got going for you

“There’s an African proverb: ‘When death finds you, may it find you alive.’ Alive means living your own damn life, not the life that your parents wanted, or the life some cultural group or political party wanted, but the life that your own soul wants to live. That’s the way to evaluate whether you are an authentic person or not.”

— Michael Meade

“The best thing you’ve got going for you,” she told me, “is your originality.”

She said, “It’s like there are two sides to you. There’s the perverse, bold, rebellious side. That’s the side that gets pissed off. That’s the side that questions everything.

“And then there’s the conventional side, that wants to hunker down and keep safe, fit in. It gets scared and uneasy about what your other side compels you to do.”

She said, “It won’t be your conventional side that makes you successful.”

She said, “You can’t live a conventional life because you’re no good at it and it doesn’t make you whole.”

It’s like we have two lives inside us: the life we’re supposed to live, and the life of the soul.

We learn to navigate the world around us, the expectations of others, we accommodate and compromise until something happens and it all breaks down. We hit a crisis point.

The life of the soul sends up a flare: hey, I’m dying here, pay attention.

The old strategies don’t work anymore. The compromises you made between the outer life and the inner life start to feel like a deal with the devil.

And we have ourselves an identity crisis.

At the time, it feels like hell. There’s loss involved: something was taken from you. Or maybe you’re forced to let it go. Or maybe it never belonged to you in the first place and you finally have to accept that.

The life of the soul demands these acts of truth.

We talk so much about being authentic; we talk less about what that actually means. Just be yourself, we say – but if it was that easy, we wouldn’t have to say it, and we wouldn’t find authenticity so remarkable that we’re constantly remarking on it.

To be original is to go against everything we learned in childhood. We were punished when we stepped outside the lines, and if our parents didn’t do it, we did it to each other. We beat each other into the right kind of manhood. We shamed each other into proper girlhood.

We learned to be unique and special so long as we’re like everybody else.

That urge to be safe – from the shaming, the beating – is so strong we’ll sell our souls for it. But when we do that, what’s left? Things keep breaking down. Life becomes a series of crisis points. We get expert at ways to numb out.

The only thing we have, in the end, is our originality. We need to honor it.

The rest is a sham.

September 23, 2012

the part of ‘being creative’ we don’t talk much about

“Far better to live your own path imperfectly than to live another’s perfectly.” -Bhagavad Gita

“Creativity comes from a conflict of ideas.” – Donatella Versace

1

So much of creative work feels like groping in the dark.

Jonathan Fields refers to it as “embracing the thrash” and Sally Hogshead to “sitting in the throne of agony.”

Both of them say the same thing: you gotta do it.

Embrace the thrash.

Sit in the chair, no matter how bad those electric shocks get.

It’s the part of the process we don’t talk much about. Ambiguity makes us uncomfortable; we want to resolve it fast, or skip over it altogether.

We would like to think that someone’s sparkling, crystal-clear vision for their novel or product or company or life leaped magically out of their skull, like Athena being born out of Zeus’s forehead with nary a labor pain. (Of course, this was because Zeus ate her mother, but regardless.)

The first stage of creativity is a period of preparation: identifying and framing the problem, gathering all your materials, your knowledge and research and experiences.

Then you enter the stage of incubation: where those materials combine and recombine and meld and transfigure and wrestle and bake and thrash out into something new.

That ‘something new’ is the stage of illumination: the eureka moment, the insight, the vision.

(Then you head into the stages of tweaking, evaluation and revision, which I won’t go into here.)

The problem is — as Fields noted in his post — that when we tell the stories of the great creators (whether it’s Picasso or Steve Jobs or JK Rowling), we begin at their moment of illumination – their eureka – as if that was the beginning of their process. But in fact it’s midway through. They’d been learning and practicing and inquiring and seeking and wandering the wilderness for years.

They’d gone all the way up to their own personal cutting edge –

– and found what lay beyond.

2

In his new book, SO GOOD THEY CAN’T IGNORE YOU, Cal Newport refers to “the adjacent possible”, a term he took from Steven Johnson, who in turn took it from complex-system biologist Stuart Kauffman.

Johnson uses it to describe the formation of new ideas.

New ideas can only be made by combining ideas that already exist “in the space of the adjacent possible”, defined by the current structures of what we already see and think and measure and know.

To get to something new, we have to get to the very edge of those ideas — and go beyond.

“We take the ideas we’ve inherited or that we’ve stumbled across, and we jigger them together into some new shape….The next big ideas in any field are found right beyond the current cutting edge, in the adjacent space that contains the possible new combinations of existing ideas.

The reason important discoveries often happen multiple times, therefore, is that they only become possible once they enter the adjacent possible, at which point anyone surveying this space – that is, those who are the current cutting edge – will notice the same innovations waiting to happen.”

Newport takes this idea and applies it to figuring out the mission, the vision, for your career.

(I would apply it to any breakthrough work of creativity.)

“A good mission…is an innovation waiting to be discovered in the adjacent possible of your field. If you want to identify a mission for your working life, therefore, you must first get to the cutting edge – the only place where these missions become visible.”

Otherwise all you do is reinvent the wheel. Lots of enthusiasm, as Newport points out, and little to show for it:

“If life-transforming missions could be found with just a little navel-gazing and an optimistic attitude, changing the world would be commonplace. But it’s not commonplace; it’s instead quite rare. This rareness….is because these breakthroughs require that you first get to the cutting edge, and this is hard – the type of hardness that most of us try to avoid in our working lives.”

In other words, you’re unlikely to hit on the compelling vision for your work — or your life — when you’re an undergraduate, or at the beginning of your working life, or simply coasting. You can’t see enough from that vantage point.

It’s only when you make it through the creative gap — do the stuff that other people won’t and master some niche in your field — explore and experiment and develop skills that create real, tangible value in the world — learn and practice and thrash and grope your way toward your own personal cutting edge.

Then you can look and – eureka – see what’s there.

What compels and inspires you.

What you can do, and contribute; how you can serve the world in a way that’s unique to you and necessary for the world; and for which you’ll be rewarded.

September 19, 2012

how a woman can write to change the world

“Powerlessness and silence go together.” — Margaret Atwood

1

So Vogue got all literary and did an Edith Wharton spread to commemorate the grand dame’s 150th birthday. But there’s a problem. We see Edith and her friends kicking it at The Mount, Edith’s country home. Living male writers depict deceased male writers:

“There is Jeffrey Eugenides in a bowler hat doing his best Henry James. There is a bow-tied Junot Diaz as Wharton’s (unrequited) love interest, diplomat Walter Berry. There is Jonathan Safran Foer, hair severely parted down the middle, posing as Wharton’s collaborator, the architect Ogden Codman, Jr.”

And the woman depicting Edith Wharton herself?

30-year-old Russian supermodel Natalia Vodianova.

As I would tweet on Twitter: *Headdesk*.

Apparently Vogue decided not to include any female writers in a feature about — brace yourself — a female writer.

On the one hand, this seems stupid.

On the other, perhaps it’s sadly and weirdly appropriate. Not because Edith’s time lacked for accomplished women writers or because said writers resembled Russian supermodels (don’t we all?)….but because as women we seem to have this habit of modestly removing ourselves from the spotlight and giving it up to the menfolk.

It’s entirely possible that Vogue approached some female writer, somewhere*, and she said in response, Oh no, your pages are too glossy for me, why don’t you let Jeffrey do his Henry James impression, it’s a kick, you’ll never look at PORTRAIT OF A LADY the same way again!

(Not that I think this happened. I don’t. This is an awkward attempt to segue.)

After all, TEDXWomen came into being because women kept turning down invitations to speak at the regular TED, politely demurring to their “more qualified” male colleagues. The organizers figured that an all-female TED conference would force the women not to do this.

“We silence ourselves,” said Katherine Lanpher at a seminar I went to last Saturday called WRITE TO CHANGE THE WORLD. It’s part of THE OP-ED PROJECT, dedicated to training female and minority voices – getting them into the op-ed pages, into key community forums, into the world.

As the Project points out

“Who narrates the world?….Most of the voices and ideas that we hear in the world come from an extremely narrow echo chamber – mostly western, white, privileged, and overwhelmingly male.”

A big part of this is because women don’t participate in these conversations with anywhere near the same frequency that men do.

“At the Washington Post, for example, a five-month tracking found that roughly 90% of op-end submissions come from men – and about 88% of Post bylines are male. If you think about it, women are actually being fairly represented, in relationship to our participation/submission radio.”

This is a problem, because:

• it suggests that women aren’t leaders or thought leaders

• who tells the story – who narrates the world — writes history. If you don’t tell your story, someone else tells it for you – and not with your interests in mind

• a public conversation that excludes half the population robs all of us of the kind of full-bodied perspective we need to make the best decisions

And because, as Margaret Atwood put it:

“A word after a word after a word is power.”

2

When I was growing up, my father was always telling me not to interrupt people. I was never a rude kid, but I could light up during a conversation. I would get so passionate and excited that my father would interrupt me interrupting someone else in order to tell me, loudly and firmly, not to do that.

As I got older, I noticed something. There were certain, male-dominated situations – be it a dinner party involving my ex and his friends, or a discussion about zombie literature at which I was the only female panelist – where I discovered that asserting myself felt dangerously close to interrupting. But if I didn’t do it – if I didn’t jump into the fray and compete for my share of attention — then I didn’t get to speak and be heard. Period.

After being trained all through my childhood and adolescence not to interrupt, I had to teach myself how to do exactly that – or at least, how to interrupt the men who were interrupting me — hopefully in a way that wasn’t completely obnoxious.

This involved climbing out of what I’ve come to think of as ‘the good girl box’.

Good girls don’t put themselves out there, throw down the conversational gauntlet, express intense and passionate opinions (at least not without apologizing profusely). After all, we might come off as too loud, too obnoxious. We might offend people. Piss people off. We might take up too much space. Attract too much attention.

A good girl is never too much of anything. She’s perfect. She’s always just right.

It may seem outdated — and it is — but it’s also the cultural legacy we’re still shaking off.

Being a good girl is about being small, sweet and quiet.

Putting ourselves out there isn’t quote-unquote feminine.

When we speak up, we step outside of that role and make ourselves vulnerable. We open ourselves up to criticism and attack.

I’m reading shame and vulnerability researcher Brene Brown’s new book, and she has some interesting observations about what she experienced when her TEDXHouston talk went viral. She bravely opened herself up to connect with the audience and drive home her argument. She put herself out there. As she watched the video of that talk race across the world, she admits to feeling “exposed” and wanting to hide. She wanted her husband to hack the TED website and bring it all down.

She writes:

“That was when I realized that I had unconsciously worked throughout my career to keep my work small.”

(It’s safer in the shadows. It’s safer to be small.)

Online, people made mean-spirited comments about her weight (“How can she talk about worthiness when she clearly needs to lose fifteen pounds?”) and her mothering (“I feel sorry for her children”) and her face (“Less research. More Botox.”).

Brown urges us to

“Think about how and what they chose to attack. They went after my appearance and my mothering – two kill shots taken straight from the list of feminine norms. They didn’t go after my intellect or arguments. That wouldn’t hurt enough.”

3

This isn’t to say that men don’t get attacked when they put themselves out there, when they open up some vulnerability of their own. When I suggested that the reticence to speak up “was a woman thing”, Katherine Lanpher was quick to correct me: “It’s also a cultural thing,” she said, referring to men of certain minority groups who also happen to be underrepresented in the forums of public opinion.

At the same time, I can’t help remembering something that acclaimed novelist Zadie Smith said during a talk at UCLA. She found it a lot easier, she told us, to get under the skin of a character from a different race or culture than one from the opposite sex. She considered the male and female viewpoints to have some fundamental differences between them, and she did her best to honor this when writing the perspectives of her male characters.

But when men narrate the world – or roughly 87% of it – that means there’s a depth and breadth of female perspective that is not being honored, whether it’s in the op-ed section of your local paper or the halls of Congress.

So we need to speak up and speak out. Get our voices out there. Put our stamp on the corporate world, on public policy, on culture. Help each other navigate the attempts to shame us whenever we step away from the good girl box, whenever we put ourselves in front of the camera not because of how we look but because of what we’ve got to say.

It’s time to write ourselves all through the story of the world — so we can work to change it.

September 16, 2012

the problem with malcolm gladwell’s “10,000 hour rule”

1

Greatness comes at a cost: ten thousand hours.

So goes the “10,000 hour rule”, which – as you probably know, so say it with me boys and girls – Malcolm Gladwell popularized in his book OUTLIERS.

To become world-class at anything requires that you put in your ten thousand hours – roughly ten years – of practice.

(It’s actually a bit more complicated than that: it can’t be just coasting-mindlessly-on-autopilot practice, it has to be deliberate practice.)

It seems that men have an edge on women when it comes to accumulating those hours. Psychiatrist Linda Austin writes that from a young age, girls tend to be interested in “learning about the human world” which manifests itself in a passion for human issues and “a broad range of diverse interests”:

“…even women choosing majors in traditionally male fields such as biological sciences, fisheries, forestry, engineering, mathematics and business administration expressed significantly greater interest in the arts and service than males did.”

Boys tend to narrow and focus their interests while still in high school, often to math, science and technical fields. By the time they are in their mid-twenties, they might already be close to achieving those ten thousand hours.

Gifted young women, on the other hand, are likely to major in psychology or anthropology or sociology or political science. They might work for a few years before deciding to go to graduate school. They might take some time out to have children. They might go to work for an agency, institution or foundation, and as they develop skills and lean into strengths they discover the niche in which they want to specialize. Austin points out that because of this more circuitous path, a woman might arrive at her area of specialization

“….relatively late [so] her timetable will be different than her friend’s in engineering. Yet studies have shown that careers that begin at a later age can have the same trajectory of excellence as those started in young adulthood – the peak of achievement is just reached later in life.”

2

But the world is a shifting and unpredictable place. As Frans Johansson points out in his new book THE CLICK MOMENT, randomness plays a greater role in Being Successful than we’d like to think.

Writes Johansson:

“We can list countless individuals who have become leaders in their fields and industries with little practice or training. Richard Branson launched Virgin Atlantic Airways on a whim, more or less, despite having zero experience running an airline. No 10,000 hours needed….”

Johansson points to Reed Hastings, who founded Netflix despite his lack of media or video experience; Niklas Zennstrom and Janus Friis, who founded Skype with limited telecommunications experience; Shigeru Miyamoto, who designed and produced Donkey Kong, one of the biggest arcade game hits of all time and exactly Shigeru’s third game; Stephanie Meyer, who hit the big time with a little YA series called TWILIGHT (you might have heard of it) despite her lack of writing practice (which some would say is reflected in Meyer’s less-than-critically-acclaimed writing style, but nevertheless); Diane Von Furstenberg, who created a key staple of almost any woman’s wardrobe – the wrap dress – while still a fashion-business newbie.

The difference between someone like Serena Williams (who racked up her ten thousand hours before she found success) and Richard Branson (who didn’t) has everything to do with their respective domains.

Tennis has rules, standards, specifications and guidelines that were pretty much the same now as when they were written, and are likely to remain the same twenty or fifty years from now.

Tennis, chess, classical music or any other discipline that responds well to the ten thousand hour rule is a

“fixed system that limits creativity and doesn’t allow for exceptions, which means you can get to know it inside out and practice your way to the top. There are strengths and strategies, yes, but you can count these on two hands and two feet.”

When you’re playing the same game over and over again, what worked in the past is likely to work again in the future.

But when the rules of the game change all the time, what worked in the past might not be relevant anymore, either because it no longer applies….or because everybody else is doing the same damn thing. In this world, you might not need ten thousand hours so much as what Johansson calls “the click moment”, the unique insight that changes everything – that turns a skirt and a top into a wrap dress, or an mp3 player into iPod and iTunes, or a dream into a bestselling YA vampire series in which vampires walk around in daylight and fall in love with human girls.

In this game, taking the ‘logical’ approach might not be so logical.

You need to do something magical.

“Unique insights are one of a kind; they are random, unexpected, and serendipitous.”

Unique insights don’t just change the game; they stand the game on its head.

3

To harness the powers of randomness and increase your odds of stumbling into a click moment of your own, Johansson recommends that you

Take your eyes off the ball.

• explore things not directly related to your immediate goal

• connect with the possibilities around you

• free yourself up to become aware of hidden opportunities

Use “intersectional thinking”

• search for inspiration in fields, industries, cultures different from your own

• surround yourself with different types of people

• attend conferences, lectures, museums outside of your discipline

Follow your curiosity

• curiosity is your intuition telling you that “something interesting is going on”

• curiosity compels you to dig and dig until you can finally connect the pieces

• curiosity clues you in to what’s different and new, unknown, unexplained

• chasing your curiosity allows serendipity to happen

Reject the predictable path

• actively rejecting the predictable insight leaves you nowhere else to go except by

making unpredictable connections

4

I believe in the pursuit of mastery. Whatever you decide to do, the way to security is to get incredibly great at it – “so good they can’t ignore you” as Cal Newport likes to say.

I believe in the power of click moments. Most of us are not living and working within a world of fixed rules, where the landscape is constant and certain.

We are creators, artists, entrepreneurs, badasses of one type or another; we’re not just living in a world of change, we’re the ones trying to bring change.

Linda Austin compares the narrowed and focused intelligence she considers typical of men to a laserbeam. She compares the wide-ranging intelligence she considers typical of women to a halogen light bulb. The former is fierce, focused, burning through obstacles; the latter is soft, diffusive, illuminating what’s around it.

The female challenge is to find a way to bring her interests together, to discover or create a point of intersection, to gather up the light of her intellect and channel it fiercely in order to blaze a new path.

At the same time, the breadth of her interests helps create the conditions that Johansson explains as necessary for ‘click moments’. In which case, men might want to take that hard focus and diffuse it a bit, to widen their intellectual framework and find some intersections of their own.

the problem with malcolm gladwell’s “10,000 hours rule”

1

Greatness comes at a cost: ten thousand hours.

So goes the “10,000 hour rule”, which – as you probably know, so say it with me boys and girls – Malcolm Gladwell popularized in his book OUTLIERS.

To become world-class at anything requires that you put in your ten thousand hours – roughly ten years – of practice.

(It’s actually a bit more complicated than that: it can’t be just coasting-mindlessly-on-autopilot practice, it has to be deliberate practice.)

It seems that men have an edge on women when it comes to accumulating those hours. Psychiatrist Linda Austin writes that from a young age, girls tend to be interested in “learning about the human world” which manifests itself in a passion for human issues and “a broad range of diverse interests”:

“…even women choosing majors in traditionally male fields such as biological sciences, fisheries, forestry, engineering, mathematics and business administration expressed significantly greater interest in the arts and service than males did.”

Boys tend to narrow and focus their interests while still in high school, often to math, science and technical fields. By the time they are in their mid-twenties, they might already be close to achieving those ten thousand hours.

Gifted young women, on the other hand, are likely to major in psychology or anthropology or sociology or political science. They might work for a few years before deciding to go to graduate school. They might take some time out to have children. They might go to work for an agency, institution or foundation, and as they develop skills and lean into strengths they discover the niche in which they want to specialize. Austin points out that because of this more circuitous path, a woman might arrive at her area of specialization

“….relatively late [so] her timetable will be different than her friend’s in engineering. Yet studies have shown that careers that begin at a later age can have the same trajectory of excellence as those started in young adulthood – the peak of achievement is just reached later in life.”

2

But the world is a shifting and unpredictable place. As Frans Johansson points out in his new book THE CLICK MOMENT, randomness plays a greater role in Being Successful than we’d like to think.

Writes Johansson:

“We can list countless individuals who have become leaders in their fields and industries with little practice or training. Richard Branson launched Virgin Atlantic Airways on a whim, more or less, despite having zero experience running an airline. No 10,000 hours needed….”

Johansson points to Reed Hastings, who founded Netflix despite his lack of media or video experience; Niklas Zennstrom and Janus Friis, who founded Skype with limited telecommunications experience; Shigeru Miyamoto, who designed and produced Donkey Kong, one of the biggest arcade game hits of all time and exactly Shigeru’s third game; or Stephanie Meyer, who hit the big time with a little YA series called TWILIGHT (you might have heard of it) despite her lack of writing practice (which some would say is reflected in Meyer’s less-than-critically-acclaimed writing style, but nevertheless); or Diane Von Furstenberg, who created a key staple of almost any woman’s wardrobe – the wrap dress – while still a fashion-business newbie.

The difference between someone like Serena Williams (who racked up her ten thousand hours before she found success) and Richard Branson (who didn’t) has everything to do with their respective domains.

Tennis has rules, standards, specifications and guidelines that were pretty much the same now as when they were written, and are likely to remain the same twenty or fifty years from now.

Tennis, chess, classical music or any other discipline that responds well to the ten thousand hour rule is a

“fixed system that limits creativity and doesn’t allow for exceptions, which means you can get to know it inside out and practice your way to the top. There are strengths and strategies, yes, but you can count these on two hands and two feet.”

When you’re playing the same game over and over again, what worked in the past is likely to work again in the future.

But when the rules of the game change all the time, what worked in the past might not be relevant anymore, either because it no longer applies….or because everybody else is doing the same damn thing. In this world, you might not need ten thousand hours so much as what Johansson calls “the click moment”, the unique insight that changes everything – that turns a skirt and a top into a wrap dress, or an mp3 player into iPod and iTunes, or a dream into a bestselling YA vampire series in which vampires walk around in daylight and fall in love with human girls.

In this game, taking the ‘logical’ approach might not be so logical.

You need to do something magical.

“Unique insights are one of a kind; they are random, unexpected, and serendipitous.”

Unique insights don’t just change the game; they stand the game on its head.

3

To harness the powers of randomness and increase your odds of stumbling into a click moment of your own, Johansson recommends that you

Take your eyes off the ball.

• explore things not directly related to your immediate goal

• connect with the possibilities around you

• free yourself up to become aware of hidden opportunities

Use “intersectional thinking”

• search for inspiration in fields, industries, cultures different from your own

• surround yourself with different types of people

• attend conferences, lectures, museums outside of your discipline

Follow your curiosity

• curiosity is your intuition telling you that “something interesting is going on”

• curiosity compels you to dig and dig until you can finally connect the pieces

• curiosity clues you in to what’s different and new, unknown, unexplained

• chasing your curiosity allows serendipity to happen

Reject the predictable path

• actively rejecting the predictable insight leaves you nowhere else to go except by

making unpredictable connections

4

I believe in the pursuit of mastery. Whatever you decide to do, the way to security is to get incredibly great at it – “so good they can’t ignore you” as Cal Newport likes to say.

I believe in the power of click moments. Most of us are not living and working within a world of fixed rules, where the landscape is constant and certain.

We are creators, artists, entrepreneurs, badasses of one type or another; we’re not just living in a world of change, we’re the ones trying to bring change.

Linda Austin compares the narrowed and focused intelligence she considers typical of men to a laserbeam. She compares the wide-ranging intelligence she considers typical of women to a halogen light bulb. The former is fierce, focused, burning through obstacles; the latter is soft, diffusive, illuminating what’s around it.

The female challenge is to find a way to bring her interests together, to discover or create a point of intersection, to gather up the light of her intellect and channel it fiercely in order to blaze a new path.

At the same time, the breadth and diversity of her interests helps create the conditions that Johansson explains as necessary for ‘click moments’. In which case, men might want to take that hard focus and diffuse it a bit, to widen their intellectual framework and find some intersections of their own.