Vaughn R. Demont's Blog

February 6, 2019

Book Club: Guilty Pleasures

Guilty Pleasures (Anita Blake #1)

by Laurell K. Hamilton

Genre: Paranormal Romance/Urban Fantasy

Setting is the silent character in the cast. In Laurell K. Hamilton’s Guilty Pleasures, which is the beginning of the “Anita Blake: Vampire Hunter” series, the chosen setting is that of St. Louis, Missouri, in an alternate history where vampirism, lycanthropy, and voodoo are all real working pieces of American society, complete with court cases and bureaucracy to back it all up. However, the setting is never truly established as a character. It is never made clear why this story could have only happened in St. Louis.

Granted,

there are slight touches of description, such as the summer heat and humidity,

descriptions of streets that I’m sure actually exist, an obligatory mention of the

Arch, but having never visited St. Louis personally, I never really felt like I

was in St. Louis.

As

Hamilton puts forth in her alternate history of the country, vampires are given

civil rights due to specific court cases, as the existence of the undead brings

up many legal questions pertaining to probate law, primarily. However, they are

established as citizens of the United States with the ability to own property,

vote, etc. Essentially, they can live wherever they can afford to. While it is

understandable that vampires settle in cities (for better access to “food”),

Hamilton posits that St. Louis makes an ideal location for a “mainstream”

vampire community, namely one which is settled and assimilated into society.

However, it is simply given as a given, there is no real justification. The

question of “why do vampires prefer sweltering heat, and if they do, why wasn’t

this placed in Los Angeles?” is raised, and never truly answered. That Hamilton

herself lives in St. Louis can be given as a reason, but if anything, it only

places a greater burden on the author make the setting more believable, as well

as its place in the story.

It

is also suggested in the novel that the alternate St. Louis takes a sort of

pride in its vampire community, though the reasoning is never spelled out,

though it is hinted that it’s more of their ability to be a tourist attraction

(as they all settle in a specific neighborhood referred to as “The District”,

easily accessible by the public) than anything else. There’s also suggestions

that the vampire community is seen as less threatening to white middle-class

America than communities in other cities due to their ability to assimilate and

mimic mainstream cultures with churches and nightclubs and a lot of good P.R.,

but still, that fails to establish how St. Louis would be unique in that level

of tolerance and acceptance. If mainstream mimicry was all that was needed, why

not the suburbs of Philadelphia or Grosse Point outside of Detroit? If weather

is an issue, why not Austin, Texas?

While

the novel is primarily character and conflict driven rather than setting

driven, the setting must still be viable and real. It’s the world that the

characters inhabit and live in, and where they choose to live should be

justified.

Reading

this novel made me realize that the setting must be well-established even in a

primarily character driven story. Though my novel is not set in a specific real

world location, The City is still an urban area, and it should be established

that the story that is being told could only be told in an urban area, possibly

through mentions of greater tolerance or simply greater indifference in an

urban area to the supernatural happenings that happen in plain sight of the

public.

December 3, 2018

For Higher Education to Survive, Adjuncting Needs to Die

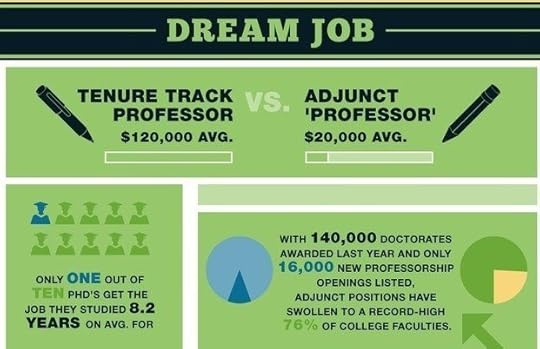

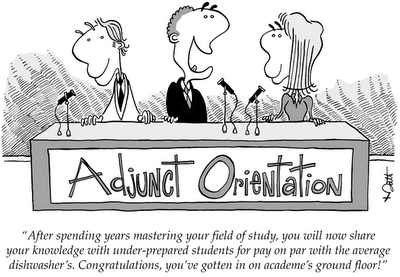

It started as a way to give retired professors something to do. The professor would be offered one class, maybe two, but not be hired back full time (as that would interfere with pensions), but hold onto the joy of educating students, working with young people, and passing on knowledge. At the end, they would be given an honorarium, for their work and trouble, not so much that it would trouble retirement benefits, and they could continue doing so until they died. In the 1960s, these professors, or adjuncts, would comprise 25% of the workforce. Today, they comprise more than half.

An Adjunct Instructor/Professor will make on average $25,000 a year, compared to full-time faculty that average $55,300 for the year, with a slightly higher course-load, tenured job security, full benefits, and medical coverage. Adjuncts rarely receive such benefits, and in fact were harmed by the Affordable Care Act, or rather, harmed by colleges and universities that cut pay, and class load to prevent adjuncts from receiving federally mandated offers of employer-based health coverage. Instead, adjuncts are often instructed to attend meetings where they will be given guidance on how to apply for Medicaid and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), more commonly known as “food stamps” (though in the US traditional paper stamps have been espoused for EBT methods). Be reminded that in order to become an adjunct professor, colleges require at minimum a master’s degree in the chosen field, an academic achievement that will often accrue over $60,000 in student loan debt, and not uncommonly in excess of $100,000.

Primarily, I believe, the reason for the abhorrent treatment of adjuncts could simply be applied to supply and demand. Considering the large output of graduates with master’s degrees, particularly in the humanities, for-profit colleges, community colleges, and four-year colleges and universities could be either more choosy in who they chose to hire, or, in the case of most US colleges, expand their programs by way of supplementing department needs with what could be best described as freelance academics.

What I believe is the reason for this expansion is this: adjuncts are rarely, if ever, asked to teach upper-division courses, often assigned to remedial, required, or general education courses assigned to college freshmen. With an incoming freshman class, attrition is at its highest, but they are a veritable cash cow of federal student aid in the form of loans, grants, and financed tuition payments. As full-time faculty are only required to teach so many introductory courses, adjuncts are brought on to pick up the slack either created by a lack of full-time faculty, or a glut of introductory sections added in the weeks before the start of a semester. It is not at all uncommon for an adjunct instructor to be held in limbo on whether or not they will be working until 72 hours before the start of the semester, sometimes learning of a course offer on the literal first day of class. This is only accomplished by assigned department mandated syllabi that can be taught by anyone with a reasonable understanding of the subject matter (hence only a bachelor’s degree being required at some online schools).

If the question is asked of why universities don’t simply hire more teachers to lessen course-loads, or give more than a cookie-cutter syllabus for an introductory course, the answer can be seen as a purely capitalist response. As an example, we will consider the cost/benefit of a freshman English class.

Let us suppose that a college charges its students $408 per credit hour (A typical rate for a community college). As Freshman English is a 3.0 hour course, the tuition cost rises to $1,224 to pay for the class, not including price of books. A filled class roster is 25 students to 1 instructor, bringing the initial tuition revenue to $30,600. A full-time professor making $55,000 must teach four total classes to maintain full-time status. Office hours, department meetings, and student advisement are considered to comprise 33% of a full-timer’s workload, but 25% by conservative estimates, making for an estimate of $41,250 paid for their time spent in a classroom and grading papers/assignments, and having office hours, bringing their pay per class to $10,312, plus additional costs for medical coverage, union protections, and retirement matching. An adjunct instructor is paid $3500 flat, on average, for the same academic labor, with no additional cost for medical coverage, retirement matching, or union protections, because those are not offered to part-time faculty. Returning the to $30,600 tuition revenue, subtracting pay for the instructor, the college can consider a profit of $20,288 with a full-time instructor, versus $27,100 with an adjunct. Now consider that the college will offer 95 sections to accommodate an incoming class of 2400 students. The potential profit changes from $1,927, 360 by hiring full timers to cover the course load, versus $2,574,000 by utilizing adjuncts. An additional $650,000 in profit for just one course, required and assigned to incoming freshmen who have to often take three to four other classes that are just as required.

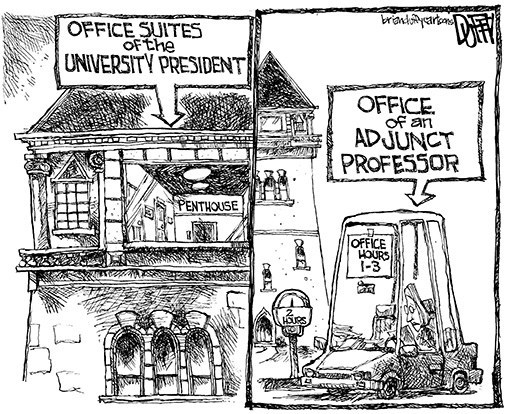

The reliance on adjuncts results in justifications for administrative bloat, with new positions created on a yearly basis with six-figure salaries to further entrench the need for low-paid faculty to pay for skyrocketing administrative budgets that do little to reduce attrition or improve enrollment. With the aforementioned glut of graduates holding masters and other terminal degrees, especially in the humanities, adjunct work is often plentiful in the fall, and non-existent in the spring.

As adjuncts are primarily assigned courses that are required for freshmen, syllabi are often assigned as well, with textbooks already chosen, and assignments set in stone as department requirements. While this can be helpful for some incoming students who come from uniformly designed curriculums, others may see the work as “more of the same”. This argument is covered in Rebecca Cox’s study The College Fear Factor: How Students and Professors Misunderstand Each Other, where Cox reviews a 5 year embedded study at community colleges to determine the reason for increasing student attrition rates and lessening satisfaction both on the student and faculty levels in 2002. By reducing the allowance for creative approaches to pedagogy, or student input on course direction, it’s only the surprise that students adopting a “get it over with” or “Cs Get Degrees” mentality, or that assigning the same cookie-cutter syllabi for repeated semesters results in an uptick of plagiarism, is at all surprising to educators. By issuing course syllabi and schedules to incoming adjuncts to be followed verbatim with no deviation, the course material results in not only being non-engaging for students, but non-challenging for professors, causing a drop in satisfaction on both sides of the classroom.

The counterargument, understandably, would come from adjuncts themselves, as the work, no matter how underpaid or underserved, is often the only source of income that such academics believe is available to them, as education is deemed a necessary field by society, but a dead end as far as career choice is concerned. Despite stories of adjuncts living in their cars, working multiple jobs, or sometimes even entering the sex industry to afford increasing costs of living that don’t match stagnating adjunct wages, adjuncts return to colleges semester after semester looking for work, and shout in fruitless indignation when their tribulations go unnoticed, or more commonly, not cared about. That adjuncts are so willing to suffer disrespect, low pay, zero-to-little benefits, and scarce representation in the way of union action or political advocacy speaks not only to their devotion to their work, but also their crippling attitude regarding the worth of their profession, an attitude that is readily conditioned by college administrations.

It is not uncommon for new adjuncts to enter into the profession with the suggestion that work as an adjunct will provide the necessary classroom experience and time spent in academia to fulfill requirements to ascend to the first steps of the tenure track. This idea is readily fostered by departments and administrations to recruit students fresh from graduate school or secondary education to make the leap into the education arm of academia, though the vast majority of new or open tenure-track positions are filled by outside hires or “friends” of administrations and department heads. To make it through the first round of interviews for an open tenure-track position is considered a rarity among adjuncts, and some adjuncts leave adjunct experience off of their curriculum vitae for fear of being tossed aside. However, unless one is willing and able to look worldwide in their search for full-time positions, adjuncting at local colleges is often the only available avenue for education’s working poor, leaving advancement to more affluent and privileged (read: white middle class) educators.

Still, the promise of potential advancement is often enough for administrations and departments to keep unruly adjuncts in line. Like the elementary school threat of the “permanent record”, adjuncts work in fear and anxiety that any appearances of not being a

“team player” will permanently erase any chances to advancement to the tenure track, even though, in reality, such chances will never truly materialize. Administrations capitalize on these anxieties by lumping additional responsibilities onto adjuncts that they are neither trained, qualified, or paid for, such as student advocacy, recruitment, attrition prevention, counseling, and constant vigilance of any student that might pose a physical threat to themselves or others, all for a salary that pays, on average, less than a job at McDonald’s, a career that does not require even a high school diploma. To rebel, complain, or even publicly note that treatment is unfair is often only done anonymously to prevent any loss of class assignments, or classes being cancelled or given to more collaborative adjuncts.

It is because of this that it is not unheard of for adjuncts to be compared to the lower-half of an abusive relationship, as adjuncts live under administrations that dictate their schedules, pay, and health coverage, literally putting administrations in control of an adjunct’s physical, financial, and emotional well-being. This treatment, of course, is steered for the benefit of administration, with little to no concern given to those abused, and threatening the only aspect of the work that adjuncts enjoy: teaching students. Administrations often find their Quisling collaborators in department chairs, often hand-picked by administration for their pliability and loyalty, claiming a “students first” mission statement while underserving those students they claim to exalt with exhausted, overworked, underpaid contingent faculty.

Given that freshman attrition rates rise with lowered quality of teaching experience, it is simple for colleges to heap the blame upon their underpaid adjuncts who are largely responsible for shepherding new college students through the anxiety-inducing transition from high school to college. Also, students are limited in their perspective of seeing their educational experience largely from the classroom level, with their professors the only faces visible of the institution, with administrators only names on e-mail blasts or speakers at graduation despite their six-figure salaries, and the majority of students are only concerned, understandably, for their own well-being. While some students voice shock or appalment at learning the destitute circumstances of some of their instructors, that shock rarely even reaches tweet-worthy status. Since adjuncts are paid minimally, office hours are often the gap between offered classes, and can be difficult for students to reach for one-on-one interaction to explain issues with assignments and forge connections that can help retention. Full-time faculty is paid for office hours, and are required to offer them, but contingent/adjunct faculty is not, relegating office hours as unpaid volunteer time which administrations and departments will pressure adjuncts to give, but with no offers of pay. Considering the number of adjuncts who either work at multiple schools or have multiple jobs, even volunteered hours are a difficult ask. The students, and the adjuncts, suffer, but administrations will still collect their pay. If administrations suddenly found themselves without an adjunct population to exploit, real change would have to be affected.

This is a pipe dream, of course, as luring bloat-loaded administrations away from the for-profit models of defunct online universities is nigh-impossible without government intervention, and even in vaunted liberal bastions such as New York and California, tuition hikes have always been seen as the easy solution for closing state budget gaps, given the readily available access to federal student loans, grants, and aid to cover rising costs. Attrition and retention will always been an issue at all colleges and universities, but until the non-student-based causes for that attrition is examined and addressed with real change, education will continue to suffer while those in charge of it push academia from it’s knowledge and improvement based paradigm into a for-profit model only benefitting those at the top by continuing to exploit the adjunct population. So, in order for education to recover and survive, adjuncting as a practice needs to die.

November 26, 2018

Jealous, or Crazy? The Wronged Woman and Pop Culture’s Catch-22 (Part 3)

V.

And I’m here to remind you

Of the mess you left when you went away

It’s not fair to deny me

Of the cross I bear that you gave to me

– Alanis Morissette, “You Oughta Know”

A Wronged Woman cannot be assumed to be a Scorned Woman, though it can be posited that a Scorned Woman is a Wronged Woman only seen in the wrong moment. This is shown by Beyoncé’s Lemonade, as one could apply the label of Scorned Woman to Beyoncé if the viewer only observed the video for “Hold Up”. The same can be said for the speaker in “Before He Cheats”, the woman in Barbershop vandalizing the wrong vehicle, and the speaker in Alanis Morissette’s “You Oughta Know”.

The song, released in 1995 as the lead single for her album Jagged Little Pill, portrays at first listen a prototypical Scorned Woman. The lyrics portray a woman rejected and replaced by another woman, lashing out with comparisons that she is a superior partner by stating:

An older version of me/ Is she perverted like me?/ Would she go down on you in a theater?/ Does she speak eloquently/ And would she have your baby?/ I’m sure she’ll make a really excellent mother – (Morissette, “You Oughta Know”)

The lyrics can be compared to “Hold Up”, in that both women are in the Denial phase, stating unequivocally that they are better lovers than any other woman on the side. In Beyoncé’s case, she is fighting against being replaced. In the case of Alanis, she already has been. Both women are processing the act of being wronged by their lovers, but without context, both will be seen as nothing more than “jealous” and “crazy”.

Jealousy can be easily applied to Morissette on first listen, as the lyrics are aggressive and angry, and repeatedly refer to the other woman. However, the chorus, which is repeated several times throughout the song, describe the emotional damage visited upon her by her ex-lover, the speaker as “the mess you left when you went away,” and “It’s not fair to deny me of the cross I bear that you gave to me.” This implies that she was denied any chance for closure, to leave the relationship on equal terms. The “cross I bear” line, inspired by Morissette’s Catholic upbringing, refers to the burden of pain that the speaker is forced to carry alone, which can elicit pity, sympathy, or empathy to ease the load. Instead, the ex-lover still holds power over her, as that “cross” is denied, the speaker not permitted to even be viewed as a victim. The ex-lover leaves her seeing herself as “the joke that you laid in the bed: that was me,” and left with the knowledge that she is owed his guilt, but will never receive it. Though it is not described how the speaker is denied her perception of victimhood, it can be posited that, given the treatment of Wronged Women labeled as Scorned Women, her reputation was tarnished, likely labeled as “jealous” or “crazy”, insuring that the male will be kept above suspicion, and relegating her as wrong. Popular culture then simply follows the fallacy of the false dichotomy: if she is wrong, he must be right. (Morissette, “You Oughta Know”)

Much like with “Before He Cheats”, only the moment of Denial and Anger is shown, with no context or aftermath shown, making it easy to relegate both speakers to judged as Scorned Women. No “spiritual sequel” to “You Oughta Know” was recorded, but Morissette’s 1998 follow-up album Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie can be considered a continuation of the journey if the speaker of “You Oughta Know” is assumed to be Morissette herself. This is a justified assumption given the speculation from 1995 to the present about who the subject of the lyrics was, even parodied in the How I Met Your Mother episode “P.S. I Love You,” which included a cameo by Dave Coulier, the actor most often assumed to be the subject, insisting the song isn’t about him.

The title of the follow-up album implies that Morissette is referring to herself, coming out as an “infatuation junkie”, someone addicted to the chemical highs of the first few weeks of a relationship. The album, which didn’t perform as well commercially as Jagged Little Pill, contained more introspective works, soul searching, and calling herself out for not seeing the warning signs in budding relationships, or not getting out when she did see them.

“Sympathetic Character” describes a woman caught in an abusive relationship but unable to leave out of fear: I was afraid of your complete disregard for me/ I was afraid of your temper/ I was afraid of handles being flown off of/ I was afraid of holes being punched into walls/ I was afraid of your testosterone. (Morissette, “Sympathetic Character”) The album gives no implication that this is the lover spoken of in “You Oughta Know”, and that she refers to herself as a “junkie” suggests that she has had many relationships where she was subjected to negative treatment. However, “Sympathetic Character” outlines the limited choices available to women in unequal and/or abusive relationships for fear of violent retribution, a subject explored in hundreds of creative works before. She speaks of fear of violence, of his temper, of her anger, but proclaims in the chorus, “I have as much rage as you have/ I have as much pain as you do/ I’ve lived as much hell as you have/ And I’ve kept mine bubbling under for you.” (Morissette, “Sympathetic Character”) The final line of the chorus speaks to women suffering in silence, that they feel the same anger, the same pain, survive the same trauma, but are encouraged by culture and fear to remain quiet to preserve the male’s self-image of power and strength.

The final lines, written in 1998, are topical in light of the #MeToo movement: “You were my keeper/ You were my anchor/ You were my family/ You were my savior/ And therein lay the issue/ And therein lay the problem.” (Morrisette, “Sympathetic Character”) She speaks of an abusive, manipulative male figure who takes many roles, and that his deep, tangled involvement in her life is too difficult to cut loose. While Beyoncé speaks of the difficulties of a cheating husband, Morissette speaks on a survivor’s guilt and fear of confronting and leaving an abuser, especially when the damage would extend beyond the physical. That “Sympathetic Character” was written in 1998 underlines that such concerns and fears are nothing new, and the tonality implies the truth that the issue and the problem has existed for much longer than the two decades since the song was recorded.

Morissette’s journey outlined in Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie is, like Beyoncé’s Lemonade, a journey of forgiveness, though unlike Beyoncé, Morissette focuses on forgiveness of self, and learning to be wary of abusive men in the future. Much like Beyoncé’s “All Night”, Morissette’s Wronged Woman emerges stronger, more self-assured, but warier and placing more of a premium on trust. Both women find strength not in other people, but through affirming their identities.

“That I Would Be Good” accomplishes such a purpose for Morissette, with lyrics that celebrate self-assurance and self-image despite negativity from others. She repeats throughout the work not that she will survive, or continue on, but that she will “be good”, “be grand”, or “be loved”, even if she is judged for behaviors popular culture has deemed as a negative such as going bankrupt, losing her hair, getting older, being clingy or fuming, getting a “thumbs down”, or gaining ten pounds, and concluding that she will be good “either with or without you”. (Morissette, “That I Would Be Good”)

It is important to note that Morissette’s journey does not end at embracing her self-image and strength. “Baba” and “Thank U” outline Morissette’s exploration of spirituality in India and how they brought her progress, whereas “The Couch” describes her decision to pursue therapy. “Unsent” further differs Morissette’s journey from Beyoncé’s as while the lyrics are about forgiveness, they are Morissette’s mea culpa to several men that she had harmed with her “infatuation addiction”. “Are You Still Mad?” is a listing of her flaws, ways she’d harmed relationships before they could come to fruition, assuring the listener that she is aware of her share of the blame, but that it does not mean her pain or treatment is deserved. The album outlines how the journey of the Wronged Woman can be fraught with complications and that work can be required on the self to leave both parties on equal terms, and that none of it possesses easy answers.

It is these complications that encourages popular culture to shy away, as the Scorned Woman is intended for comedies or thrillers or horrors, an easy target and scapegoat. This, however, causes damage not only to the concept of the Wronged Woman, but to women in general. That popular culture leans on the cliché of the jealous and mentally unstable woman normalizes the concept to society, and thus further Others women as a minority, particularly women of color. It permits men to mistreat women, and afterward declare any response as the result of jealousy or mental instability, absolving themselves of any blame.

Both Beyoncé and Morissette show the journeys of two Wronged Women, which take different paths, but do not invalidate each other, as a journey is not a dichotomy, false or otherwise. Both Lemonade and Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie display what is possible when a woman takes reclaims her agency over her emotions and journey to process and heal from being wronged. Both works remove the harmful caricature of the Scorned Woman to reveal the real woman beneath, and demonstrate the complicated, human realities of forgiveness of others and of self. When popular culture embraces women who reclaim their agency, a woman scorned can reveal herself as a woman wronged, and finally, rightfully, share her story.

Bibliography (Parts 1-3)

Morgan, Joan. When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: My Life as a Hip-Hop Feminist. Touchstone, 2000.

Beyoncé́, James Blake, Kendrick Lamar, The Weeknd, and Jack White. Lemonade. Parkwood Entertainment, 2017. MP3.

Underwood, Carrie. “Before He Cheats.” Some Hearts. Arista, 2005. MP3.

Kellet, Gloria Calderon. “How I Met Everyone Else.” How I Met Your Mother. CBS. 22 Oct. 2007. Television.

Carter Bays and Craig Thomas. “P.S. I Love You.” How I Met Your Mother. CBS. 4 Feb. 2013. Television.

Malins, Greg. “Swarley.” How I Met Your Mother. CBS. 6 Nov. 2006. Television.

Kang, Kourtney. “Return of the Shirt.” How I Met Your Mother. CBS. 10 Oct. 2005. Television.

Morrissette, Alanis. Supposed Former Infatuation Junkie. Royaltone Studios, Los Angeles, CA.1998. MP3.

Morrissette, Alanis. “You Oughta Know.” Jagged Little Pill. Maverick, 1995. MP3.

“Gold & Platinum.” RIAA, www.riaa.com/gold-platinum/?tab_activ....

CulturePub. “Mad Cheated Wife Destroys Husband’s Convertible.” YouTube, YouTube, 22 Jan. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Io2YpXLycIU. “Marital Bliss is better for your car!” Blake’s Auto commercial from 1996, produced by Blake’s/Jessen Ad Agency. 9 Jan. 2018.

Payne, Don, et al. My Super Ex-Girlfriend. Performance by Uma Thurman, and Luke Wilson, 20th Century Fox, 2006.

Story, Tim, et al. Barbershop. Performance by Ice Cube, and Anthony Anderson, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 2002.

Morrison, Toni. The Origin of Others. Harvard University Press. 2017.

Bibel, Sara. “TV Ratings Monday: ‘How I Met Your Mother’ Finale Hits High, ‘Bones’ & ‘The Tomorrow People’ Up, ‘The Voice’ Down”. TV by the Numbers. 1 Apr. 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

Schur, Michael. “Time Capsule.” Parks and Recreation. NBC. 3 Feb. 2011.

November 24, 2018

Jealous, or Crazy? The Wronged Woman and Pop Culture’s Catch-22: Part 2

IV.

“What’s worse, looking jealous or crazy, jealous and crazy? Or like being walked all over lately. I’d rather be crazy.” – Beyoncé, “Hold Up”

Beyoncé released her sixth studio album, and second visual album, Lemonade, in 2016 through Tidal, an artist-centric platform that she co-owned. This unique privilege provided her with the freedom of artistic expression not often available to popular and mainstream artists, particularly female ones. Lemonade provided, among other messages and statements addressed by critics, an exploration of a Wronged Woman’s journey through an unraveling marriage. It supplies the audience with the expected actions of a Scorned Woman with acts of vandalism and displays of anger, but it sets itself apart in a vital fashion, casting aside the Scorned Woman to reveal the Wronged Woman beneath.

Lemonade provides what every Scorned Woman of popular culture has been denied: context, history, and agency. The album charts the path of a woman learning of and confronting her husband’s infidelity in eleven chapters: Intuition, Denial, Anger, Apathy, Emptiness, Accountability, Reformation, Forgiveness, Resurrection, Hope, and Redemption. (Beyoncé, Lemonade) Anger is a part, but only one part of a long narrative that leads to forgiveness. Lemonade’s visual album provides deeper context, providing rich imagery to accompany the Wronged Woman’s journey.

The visual album opens with a shot from “Don’t Hurt Yourself”, the Anger phase, played at very slow speeds, the sound evoking an animal growl, and then immediately transitions to shots of a plantation, Beyoncé in the tall grass. It hooks the viewer with the shot of expected Anger phase, but refuses to allow the viewer to see the Anger without the context of the Intuition and Denial phases. The Intuition section shows the viewer a woman in solitude, on display under stage lights, alone in the fields, or standing on a building’s ledge while speaking of suspicions of her husband’s infidelity, “Pray I catch you whispering. Pray you catch me listening.” (Beyoncé, “Pray I Catch You”) It speaks of the growing uncertainty that accompanies intuition, and how it leads into the instinct that she has been wronged by her husband, but unable to find confirmation.

Intuition’s uncertainty leads to Denial, with a transition that includes adaptations of poet Warsan Shire’s, “For Women Who Are Difficult to Love.” Shire’s lines are present throughout the visual album, presenting that the journey of the Wronged Woman has received plenty of creative attention in the realms of literature, art, and poetry, but has been largely ignored by a popular culture more centered on marketability. That Lemonade, performed by an influential woman in the music industry, often breaks the music to insert Shire’s poetry elevates the imagery and lyrics which precede and follow. This inclusion informs the viewer of the wealth of literature and poetry that goes lauded by critics but ignored by consumers, providing the knowledge that a Wronged Woman’s journey has been explored before, and invites further inspection.

Denial opens with a plunge into deep water and a woman submerged, alone, describing a list of self-inflicted excoriations, placing the blame for even the potential of infidelity upon herself, stating: “Got on my knees and said Amen and said I mean. I whipped my own back and asked for dominion at your feet.” (Beyoncé, “Denial”) The implied submission is one of many lengths the speaker goes to keep the blame on herself, which she can control and affect, instead of the uncertainty of, “But still inside was coiled the need to know, ‘Are you cheating on me?’” (Beyoncé, “Denial”)

Denial’s track, “Hold Up”, supplies the viewer with the aspects of the Scorned Woman required in the cliché, in that it includes a woman, a baseball bat, and vandalism. The lyrics, while set to a cheery, upbeat reggae-style foundation, portray the anger pushing at the cracking surface of the speaker’s denial. Beyoncé, in the visual album, strolls at first stone-faced, clad in a yellow dress. The yellow is symbolic, as at first glance it implies a happy, sunny outlook, the playful tone of the song implying the listener infer the positive aspects of the color, instead of the negative symbolism of jealous, anxiety, deception, fear, and depression. Her expression changes to a more joyful one upon taking a baseball bat from a bystander and proceeding toward a car..

This is the first departure from the Scorned Woman cliché, as the blunt instrument for vandalism is not, as shown in the cliché, premeditated, but instead taken on a whim. This provides the first crack of the denial, as.her expression changes to anger when she breaks the first window, with the bystanders, much like in Barbershop, finding the action amusing. However, the woman strolls on, smiling again, implying that the window-breaking was a flash of anger flaring through her outward implication that everything is okay between her and her husband. The strikes become more frequent as the song continues, until she proceeds from smashing windows on cars to a display of wigs, which is accompanied by a gout of flame.

That the breaking of the display of wigs is done in a one-handed, almost casual manner, brings the uncertainty of her husband’s infidelity to the forefront. The context is later shown in “Sorry”, where the line, “He better call Becky with the good hair” is repeated twice. (Beyoncé, “Sorry”) Considering that “Becky” is a slang term for a white woman, and that “good hair” is usually referring to hair that is straight with no curls or kinks, usually possessed by white women, it becomes clear why the flames of rage burst in the background upon her seeing a wig with straight, white-like hair.

“Hold Up” also calls out the false dichotomy of the Scorned Woman, in that she asks if it’s worse to be seen as jealous or crazy, or accepting of the treatment. While the first two are commonly applied to women in popular culture, it’s the final that is rarely examined, that of suffering in silence. Joan Morgan calls attention to this in When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: My Life as a Hop-Hop Feminist, attacking the concept of the “StrongBlackWoman”:

…by the sole virtues of my race and gender I was supposed to be the consummate professional, handle any life crisis, be the dependable rock for every soul who need me, and, yes, the classic — require less from my lovers than they did from me because after all, I was a STRONGBLACKWOMAN and they were just ENDANGEREDBLACKMEN. (Morgan 91)

This is where Lemonade sets itself apart, as it focuses on the pressures faced not only by women, but specifically black women. When “Hold Up” asks if it’s worse to look jealous or crazy, it doesn’t just imply that the speaker is worried about her appearance to her husband, but also how society will view her as well. That fare like Barbershop proclaims that not only is jealousy or craziness on the part of the Scorned Woman is applauded, it’s expected, underscores the much more limited choices that a black Wronged Woman faces instead of her white counterparts. As Morgan states, “I’d internalized the SBW credo: No matter how bad shit gets, handle it alone, quietly, and with dignity.” (Morgan 94)

But “Hold Up” isn’t the Anger phase, it’s Denial, of wanting to believe that she hasn’t been wronged despite increasing evidence to the contrary. She takes time in the middle to proclaim that her husband likely wouldn’t be so foolish to cheat on her, because she’s the best he’ll ever have:

Let’s imagine for a moment that you never made a name for yourself/ Or mastered wealth, they had you labeled as a king/ Never made it out the cage, still out there movin’ in them streets/ Never had the baddest woman in the game up in your sheets/ Would they be down to ride?/ No, they used to hide from you, lie to you/ But y’all know we were made for each other/ So I find you and hold you down. (Beyoncé, “Hold Up”)

Instead of cliché Scorned Woman rage, the speaker affirms her identity and self-worth, claiming her husband is fortunate in his success, because she never would’ve noticed him otherwise.

Without the necessary context, Beyoncé is a cliched Scorned Woman, breaking everything in sight because she thinks her husband has been unfaithful, making her easy to relegate as “jealous, or crazy”, providing those reactions as her only options. That she states, “I’d rather be crazy”, contradicts the implication of mental instability, as her consciousness of the two perceptions she is limited to displays her rationality. (Beyoncé, “Hold Up”) Her choice to “be crazy” is the only path society allows her in order to take action instead of suffering in silence or fuming in jealousy.

The visual album shows how each phase slowly transitions into the other, as Anger follows Denial, but Lemonade shows how vital context is in regards to the Wronged Woman. Without the history and self-flagellation of the Intuition and Denial opening, “Hold Up” looks like any other Scorned Woman cliché. She takes a baseball bat to cars, windows, fire hydrants, security camera, and even concludes with driving a monster truck over a line of cars similar to those she’d been smashing throughout.

Anger is what is expected with the Scorned Woman, a cliché that is argued to be a trope. The difference between the two is that cliché is considered a lazy writer’s tool, a story mechanic that has become obsolete, and deserving of ridicule. A trope, however, is an audience expectation that a narrative will follow a specific path, and when the trope is subverted or contradicted, the audience feels frustrated or betrayed. To argue that the Scorned Woman is a trope is to argue that it is valid to expect a woman to behave irrationally when she has been wronged, and to ascribe her motivations to jealousy or mental instability, rather than allow a Wronged Woman agency over her own emotions. Why must she be limited to being seen as jealous, or crazy, when she could be frustrated, worried, depressed, anxious, fearful, worried, angry, or any other emotion?

The Anger phase of Lemonade takes the viewer back to the first shot of the album, of Beyoncé leaning against an SUV, but now, armed with the history and context, the song “Don’t Hurt Yourself” becomes much more pointed. The cliché of the Scorned Woman would require the Anger phase to be the only section seen, the section providing the most entertainment. That the poetry leading into the Anger section describes a grisly dismemberment of the woman her husband is cheating with, could lead the viewer into believing the true violence and destruction is yet to come. With an SUV featured prominently, with women draped about it, is a common image in hip-hop videos, implying that the video might feature Beyoncé destroying that SUV, a symbol of her husband’s masculinity.

Instead, the first line of “Don’t Hurt Yourself”, is “Who the fuck do you think I am?” (Beyoncé, “Don’t Hurt Yourself”) It is a line that proclaims the strength of her self-image and identity, with her accenting the profanity. The anger of the song is streamed through her words, calling her husband out for wronging her, asserting her independence with, “and keep your money, I’ve got my own. It would put a smile on my face, being alone.” (Beyoncé, “Don’t Hurt Yourself”) In those lines, Beyoncé accentuates the power that women have reclaimed: the ability to stand on their own and leave. Too often, women are forced to “be walked all over” because they lacked the resources to express their anger and follow through on a threat to leave. While it can be argued that Beyoncé has the means and resources to leave a cheating husband, the message of the song isn’t about leaving. Instead, it’s best explained by Morgan, “But recognize: Any man who doesn’t truly love himself is incapable of loving us in the healthy way we need to be loved.” (Morgan 78) This is shown in the lyrics where the speaker seeks to remind her husband of their connection, that whatever he does to her, he’s only doing to himself, concluding the with “When you love me, you love yourself.” (Beyoncé, “Don’t Hurt Yourself”) Even with the anger of the lyrics, it isn’t a song where she announces she’s leaving her husband, though she repeats in “Hold Up”, “Don’t Hurt Yourself”, and later “Sorry”, that she’s certainly willing and able to. It ends with, “This is your final warning/ You know I give you life/ If you try this shit again/ You’re going to lose your wife.” (Beyoncé, “Don’t Hurt Yourself”)

The primary departure from the Scorned Woman, and the display of the Wronged Woman’s journey is in the tracks that follow the Anger phase, and lead toward forgiveness. The album tracks and shows Beyoncé pushing forward through a lack of caring, emptiness, holding her husband accountable, and then finally forgiving him, focusing on their love and their connection. However, the wariness remains, as even after they’ve reconciled, the line, “Give you some time to prove I can trust you again” echoes the final warning of “Don’t Hurt Yourself”, informing her husband that while a Wronged Woman can forgive the one who wronged her, she won’t be wronged again. (Beyoncé, “All Night”)

Works Cited

Morgan, Joan. When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost: My Life as a Hip-Hop Feminist. Touchstone, 2000.

Beyoncé́, James Blake, Kendrick Lamar, The Weeknd, and Jack White. Lemonade. Parkwood Entertainment, 2017. MP3.

November 19, 2018

Jealous, or Crazy? The Wronged Woman and Pop Culture’s Catch-22 (An essay in 3 parts)

Part One: The Wronged Woman

I.

“Heaven has no rage like love to hatred turned, Nor hell a fury like a woman scorned.”

– The Mourning Bride, Act III, Scene 2

Begin with a symbol of masculinity: a pickup truck or luxury sedan, maybe an SUV. Any automobile will do. Add an act of infidelity on the part of the male owner. Introduce the victim of the infidelity, a woman. Give her a blunt instrument, a baseball bat or sledgehammer will do the job nicely. After that, insure that the plot follows the tropes in one of two ways: the automobile is destroyed, or, midway through the act, reveal, through a man, that the woman is vandalizing the incorrect vehicle. Conclude with someone, either in the work, or the audience, stating, smirking, “Hell hath no fury…”

The concept of a woman scorned has been part of art and popular culture for over three centuries, with “Hell hath no fury like a woman scorned” becoming embedded in common parlance. The phrase is learned through scenes in popular culture like the one described above, and applied to a singular moment of acted-upon anger to define the identity of a woman who has been wronged. Whether the woman is vindicated, celebrated, shamed, or ridiculed for that brief moment of attention can be filtered through many lenses of criticism, but it is vital that it be recognized what isn’t being given attention.

The process by which the female character reaches that moment of anger expressed is often glossed over or simply ignored. The actions taken, whether justified, cathartic, humorous, or otherwise, are treated as entertainment. This reduces the female character to a stereotype with little to no attention given to the events that led to her decision to act, and even less attention given to the aftermath, save punishment or forgiveness, and quickly moving on. The character becomes a Scorned Woman, one who acts out of jealousy or rejection, and therefore, is easy for the audience to judge and subsequently ignore. The stereotype excuses the audience from considering the complexities, as stereotypes are meant to do. Popular culture spends its attention on a woman scorned, rather than a woman wronged.

Instead of being portrayed as a revanchist cliché, the Wronged Woman is allowed her emotions, reactions, and her process. She retains control over her destiny, and her journey through a difficult time, but rarely receives cultural attention. Popular culture affords a Wronged Woman no agency over how she journeys through her mistreatment. Her options are severely limited, and regardless of her actions, she’ll be viewed as jealous, mentally unbalanced, accepting of the treatment, or left to suffer in silence.

The Wronged Woman and the Scorned Woman are usually, and incorrectly, portrayed as synonymous. The entirety of their experience is cut and edited from the many-faceted journey of forgiveness of self and others, in favor of crowd-pleasing portrayals of anger. This is seen in music, television, and film, which portray a Scorned Woman channeling her frustration through anti-social acts of cruelty, humiliation, or vandalism, all of which are carried out on a male guilty of the immoral, but not illegal, act of infidelity.

These acts are usually played for the sake of humor or vindication. In the case of humor, either the male is viewed as getting his comeuppance for his unfaithfulness, or the Scorned Woman is portrayed as so blinded by her anger that she carries out her vengeance on the wrong target, and is ridiculed as a result. With vindication, the satisfaction is shown, the Scorned Woman is triumphant, but no aftermath is shown of the consequences, legal or otherwise. Either of these results are damaging, not only because they gloss over the prelude and aftermath, but because they imply that these are the only two actions outside of doing nothing.

II.

“Well, I dug my key into the side

Of his pretty little souped-up four-wheel drive

Carved my name into his leather seats

I took a Louisville Slugger to both headlights

Slashed a hole in all four tires

Maybe next time he’ll think before he cheats”

– Carrie Underwood, “Before He Cheats”

Popular culture suggests that if a man is unfaithful, he’d best keep an eye on his car. The image of a woman vandalizing her ex-lover’s car with a baseball bat had existed for some time, but was firmly ingrained in popular culture by Carrie Underwood’s 2005 hit song, “Before He Cheats.” The lyrics feature a speaker, betrayed by her boyfriend, who describes the infidelity that her soon-to-be ex-lover is likely engaging in, and profiling the type of woman he’s likely with. The tone implies supposition, that the speaker can’t be certain, as the word “probably” is used seven times throughout the song. That implication of an unreliable narrator has given critics cause to relegate the speaker to the Scorned Woman category. By doing so, the events that lead the speaker to resort to vandalism are obscured, letting the audience believe an alleged act of infidelity was the only justification she needed to destroy a forty-thousand-dollar truck. Little attention is given to the aftermath as well, save that she “might’ve saved a little trouble for the next girl”, but nothing else regarding the journey the speaker completed. (Underwood, “Before He Cheats”)

The tone of the song, however, is one of vindication, vengeance, and catharsis. The speaker, though acting in anger, takes control and punctuates her decision to leave her unfaithful lover with her destruction of his automobile. That his “pretty little souped-up four-wheel drive” is the target is telling: it’s a symbol of his masculinity that can’t hit back. It was a message that proved successful in popular culture, as the song was certified platinum five times, providing a break-up anthem for many in its audience. (RIAA) “Before He Cheats” elicits and reinforces the revanchist mindset, celebrating the speaker’s anger, but only her anger, which provides more entertainment for the audience. However, it is thought of as an anthem for a Scorned Woman acting out of jealousy, and acting on nothing more than suspicion. Even when the song portrays the woman being in the right, she’s still limited to being jealous, mentally unstable, or both.

The destruction of a man’s car by a Scorned Woman is a trope so common it’s become cliché. In film, television, and even commercials, the Scorned Woman is treated negatively, playing into the stereotype of jealousy. The previous example of vandalizing an automobile has seen several portrayals, particularly when it implies that the Scorned Woman is so fraught with jealousy and anger that she can’t tell which car belongs to her unfaithful lover. In the mid-1990s, a commercial for an auto repair specialist shows a white woman arriving at a golf course, retrieving a sledgehammer from her own car, and proceeding to break the windshield of an expensive red convertible, decrying her husband’s infidelity while bystanders watch, but don’t intervene. The “punchline” arrives when her husband parks next to her, in the same model car, and with an indulgent expression, asks what she’s doing. (Blake’s Auto) A similar situation happens in Barbershop, where a black woman parks her car next to a silver sedan, retrieves a baseball bat, and begins smashing windows and panels, all while the neighborhood looks on, clearly entertained, but not intervening. The victim is entertained as well, unaware, commenting on how to best teach a cheater a lesson, until he realizes it’s his car being vandalized. Upon confrontation, the woman weakly offers apologies, and then escapes.

Both examples imply that vandalism is permitted, though there are clear differences. With the white woman, the onlooker is silent, not getting involved because of white social mores to not interfere in what isn’t one’s business. When the mistake is revealed, the woman is made to look foolish for not recognizing her husband’s car, or knowing his license plate. In the case of Barbershop, the onlookers all but cheer it on from a safe distance, not interfering because it’s 1) entertaining, and 2) not happening to their own vehicle. Attentive viewers even point out that the intended target of vandalism was close by, in full view of the Scorned Woman, but she was too enraged to tell the difference, providing ridicule by way of dramatic irony.

Further vandalism occurs in the 2006 superhero comedy, My Super Ex-Girlfriend, starring Uma Thurman in the titular role. The film, reviled by feminist critics, portrays as its hero a straight white male, the character shown committing sexual harassment, acts of racial insensitivity, and possessing homophobic attitudes, all of which were consistent with pop culture portrayals of white masculinity in 2006. Given the character, Matt, commits many insensitive acts over the course of the film without any real corrective action, the “Super Ex-Girlfriend”, Jenny, is portrayed as the stereotypical Scorned Woman, so much so that she is an assemblage of negative traits rather than a three-dimensional character. Jenny is shown as over-sexualized, violent, obsessive, jealous, possessive, and vindictive, ticking boxes of a harridan’s checklist as she becomes a villain. All of her actions are escalated for the sake of humor, all from the playbook of popular culture’s Scorned Woman: She doesn’t just stalk him, she floats outside of his window. She doesn’t just demand his attention, she threatens to let a missile hit a city unless he apologizes. She doesn’t just threaten violence, she throws a shark through his window. She doesn’t just vandalize his car, she puts it in high orbit. All of this is necessary to move the goalposts in the case of Matt, who normally would be considered an antagonistic character, so Jenny must be seen as much, much worse if Matt is to win the affections of the other female lead, Hannah, played by Anna Faris, who legitimizes Matt’s harassing behavior by approving of it.

My Super Ex-Girlfriend reinforced the concept of the Scorned Woman as a target of humor and ridicule, and in the process, removes any sympathy for the titular character, and thus, robbing Jenny of any sort of journey toward forgiveness or a clean break to move on. It is set apart from “Before He Cheats”, Barbershop, and the aforementioned auto repair commercial, as My Super Ex-Girlfriend doesn’t limit itself to the moment of anger, but shows the course of the relationship as well, from first meeting to dating to break-up to aftermath, but it shows every phase through a misogynistic lens, retaining the male lead as a pitiable hero throughout. That My Super Ex-Girlfriend, Barbershop, the Blake’s Auto commercial, and “Before He Cheats”, are all written by men is not surprising, as the cliché of the Scorned Woman is one that limits women instead of empowering them. The Scorned Women in those examples are only shown as jealous, mentally unbalanced, and/or raging, implying those are the only valid reactions to infidelity, suspected, confirmed, or otherwise. All of those reactions can be relegated to simple irrationality, being over-emotional, and not capable of logic, which can be taken as implying that since the Scorned Woman is those three traits, the man is in turn rational, calm, and logical. This, of course, is textbook False Dichotomy, but fallacies find fertile purchase in popular culture.

III.

Marshall Eriksen: What are you guys talking about; the ‘Crazy Eyes’?

Barney Stinson: It’s a well-documented condition of the pupils, or pupi.

Ted Mosby: Nope, just pupils.

Barney Stinson: It’s an indicator of future mental instability

Marshall Eriksen: She does not have the crazy eyes.

Ted Mosby: You just can’t see it because you’re afflicted with “haven’t been laid in a while” blindness. – How I Met Your Mother, Season 2, Episode 7

The idea that women are crazy is one that has permeated popular culture, especially in the 21st century. By referring to women as crazy, their actions can be written off as irrational, unjustifiable, or elsewise in the wrong, while male characters retain perceptions of logic, rationality, and righteousness of action. A woman’s craziness is often related through anecdote, told almost always by a male character, usually to a ridiculous end to portray the woman as so irrational that any action taken on the man’s part, before or after, is justified. That the men are unreliable narrators in their anecdotes is almost never called into question, and if it is, it’s often brushed aside and is never questioned again. Any irrationality on a man’s part is often attributed to his sexual activity, and the length of time that has passed between instances of sexual intercourse.

A pinnacle example of this is shown, though perhaps not intentionally, in the CBS sitcom series How I Met Your Mother. It is a series that at first glance defends the concept of romantic love, a story told by the narrator, Ted Mosby (played by Josh Radnor), a white cisgender heterosexual architect, thirty years in the future to his son and daughter about the events that led to him meeting their mother. It proved a popular series, lasting nine seasons, spreading many catch phrases and concepts into popular culture, often through the character Barney Stinson (played by Neil Patrick Harris), and averaged above 8 million viewers, hitting a series high of 13.13 million viewers for the series finale. (Bibel)

The series leaned often on the concept of women being crazy in order to excuse the actions of men, or to explain why a relationship ended, in the men’s perception, prematurely. The season 2 episode “Swarley” posited that a man could predict a woman’s future mental instability simply by looking in her eyes, and went to ridiculous lengths to prove its sweeping generalization, such as a woman (played by Morena Baccarin, a Brazilian-American) ransacking an entire apartment to find keys that were in plain sight, three feet from her, the whole time. These ridiculous consequences are done for the sake of humor, of course, but can have an effect on the viewer. In her lecture series, The Origin of Others, Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison speaks on the effect of popular culture:

Far from our original expectations of increased intimacy and broader knowledge, routine media presentations deploy images and language that narrow our view of what humans look like (or ought to look like) and what in fact we are like. (Morrison 37)

Though Morrison is speaking on how popular culture others non-white characters, it also touches on the expectations of behavior and appearance. The principal male characters in How I Met Your Mother are all white cisgender heterosexual men (though one is played by Neil Patrick Harris, a homosexual gay rights advocate), where the women, also white, are Othered, as Morrison describes in her lecture, either by being a Canadian woman with the character Robin (played by Cobie Smulders), or simply being a woman in the case of Lily (played by Alyson Hannigan). By being placed in the Other column, their actions can be written off as women being crazy, irrational, jealous, or violent, while the men are shown as stable providers, or can commit irrational, sometimes criminal acts of rape by deception, and not receive any social punishment.

The series applies the Scorned Woman concept several times, often targeting the “hero” of the series, Ted, treating the women as speedbumps or roadblocks between himself and the final woman, Tracy, that he is entitled to by the end of the series after all of his “suffering”. The first example of the Scorned Woman is shown in the season 1 episode “Return of the Shirt”. The episode portrays the Scorned Woman in Natalie (played by Anne Dudek), a woman that Ted ended the relationship with, over voicemail, on her birthday, years before. When Ted attempts to rekindle the relationship, she is resistant, but is swayed by Ted’s argument into giving him another chance. When Ted once again ends the relationship, on her birthday, she assaults him in a restaurant and leaves him humiliated and beaten, the moral implied to be that one doesn’t reject a woman proficient in Krav Maga. This “moral” has problems of its own besides reinforcing the Scorned Woman cliché, as Natalie is reacting to rejection, as the story implies that a woman must be skilled in self-defense to avoid being the victim instead of the man being respectful.

Much of How I Met Your Mother relies on Ted’s point of view, with the series suggesting at many points that Ted is an unreliable narrator, as he commonly forgets, misremembers, or edits the stories he’s relating to his children to increase their entertainment value and portray him as the hero of the story and others as the villains. Once it is accepted that Ted is unreliable and self-serving in his narrative, the portrayals of the women in his story and his friends become suspect.

Several times over the course of the series the backgrounds of the female characters are altered and edited, particularly with Robin and Lily. This is underlined in the episode “P.S. I Love You” which goes to great lengths to paint female characters as crazy to overshadow or excuse the behavior of Ted. The episode begins with Ted fixating on a woman he saw for less than a minute on a subway, and immediately beginning research to find her. This brings an accurate judgment of “Stalker Ted Alert” by his best friends, but almost immediately afterward the episode forgives his actions by making the actions of those around him, or, more pointedly, the women around him, far more irrational and threatening. The story of how Marshall and Lily first met, long a romantic hallmark of the series, is altered to cast Lily in a stalker role. Robin, who’d long been seen as a strong, self-reliant woman, is reduced to a literal stalker living under a restraining order. The woman that Ted is pursuing, Jeanette, is portrayed as a misogynistic mix of harridan and Scorned Woman that Ted’s friends are too happy to see given the boot. Jeanette is the most cheated character, as only behaviors that support the casting of her as a Scorned Woman are shown, denying her any history, process, or aftermath, save a throwaway mention at series end pairing her with another also-ran character that had been involved with Robin.

If Ted is an unreliable narrator, however, the above actions take a selfish intent, excusing and glorifying himself in the eyes of his children to prevent himself from being seen as flawed, or at least flawed in a way that he can laugh at as well. By accepting that Ted is unreliable, he becomes part of the problem regarding the rift between the Scorned Woman and the Wronged Woman; the former is an easy scapegoat that absolves the male of blame, while the latter challenges a male to confront his own wrongdoing.

As the series culminates in Robin being the woman Ted wanted all along, it can be implied that the ridiculous and criminal acts that Barney participated in (rape by deception, insider trading, smuggling, implied white slavery, and many more), were exaggerated to paint him as the villain, as Barney and Robin marry, with the story repeatedly portraying Ted as hopelessly in love in Robin and emotionally self-flagellating to mask his feeling of entitlement to her. When Ted fixates on a woman, she ceases being a woman, and is cast as the leading lady in his romantic fantasy. He essentially “owns” her, and goes to great lengths to insure that the fantasy plays out according to script. If his fantasy heroine “goes off book”, the relationship ends, and often she’s written off as crazy or “humorously” bitter for the sin of voiding his entitlement. That these behaviors would be diagnosed as obsessive and unhealthy is only paid lip service, indicative of double standard between men and women, as the women who committed the same behaviors as Ted were written off as “crazy”, while Ted remains the hero of the story, and entitled to the objects of his desire.

Morrison touches on this feeling of entitlement in an anecdote on a fisherwoman she meets and has a pleasant conversation with, but grows to resent once the fisherwoman disappears, denying her of any further opportunity to connect with her (Morrison 31-34):

“I immediately sentimentalized and appropriated her. Fantasized her as my own personal shaman. I owned her or wanted to (and I suspect she glimpsed it). I had forgotten the power of embedded images and stylish language to seduce, reveal, control.” (Morrison 36)

Morrison speaks on how she’d been influenced by “embedded images and stylish language” to believe that she was entitled to a connection with the fisherwoman, and when she was denied it, grew to resent her until after a course of introspection was able to see that she was not entitled to the woman’s friendship at all, that the fisherwoman was likely saying whatever would keep her from getting into trouble and thereafter make a quick escape. This idea is present in popular culture, that we are all characters in our own stories, and those outside who come into, or are pulled into our world are ours to decide whether they stay within or not, cast in the roles we choose, and are subject to our judgment and emotion when they don’t play along.

Sitcoms often enable and contribute to the stereotype of the Scorned Woman for the sake of comedy, as How I Met Your Mother shows as a pinnacle example. Other sitcoms have taken steps however, calling out such behaviors tongue firmly in cheek, as with the Michael Schur penned episode “Time Capsule” of the series Parks and Recreation, where the character Tom (played by Aziz Ansari), states:

“She broke up with me. Didn’t really tell me why. Luckily, when you’re the guy you can tell people she’s crazy. ‘Hey, Tom! I heard you and Lucy broke up!’ Yeah, man. Turns out? She’s crazy. That’s what they always do on Entourage.” (Schur)

At first read or viewing, it plays into the cliché of the Scorned Woman: Lucy broke up with Tom, ergo, Lucy is crazy. However, Tom points out the double standard. He claims no reason for Lucy ending the relationship, when it was shown in the previous episode that his own jealousy caused a rift. He points out his male privilege, stating “luckily, when you’re the guy you can tell people she’s crazy”, absolving himself of all blame, and then claiming that it’s “what they always do on Entourage,” a series that paraded toxic masculinity and entitlement. Instead of enabling it, the behavior is filtered through the lens of satire, though not outright calling it out.

Works Cited

Underwood, Carrie. “Before He Cheats.” Some Hearts. Arista, 2005. MP3.

Kellet, Gloria Calderon. “How I Met Everyone Else.” How I Met Your Mother. CBS. 22 Oct. 2007. Television.

Carter Bays and Craig Thomas. “P.S. I Love You.” How I Met Your Mother. CBS. 4 Feb. 2013. Television.

Malins, Greg. “Swarley.” How I Met Your Mother. CBS. 6 Nov. 2006. Television.

Kang, Kourtney. “Return of the Shirt.” How I Met Your Mother. CBS. 10 Oct. 2005. Television.

CulturePub. “Mad Cheated Wife Destroys Husband’s Convertible.” YouTube, YouTube, 22 Jan. 2011, www.youtube.com/watch?v=Io2YpXLycIU. “Marital Bliss is better for your car!” Blake’s Auto commercial from 1996, produced by Blake’s/Jessen Ad Agency. 9 Jan. 2018.

Payne, Don, et al. My Super Ex-Girlfriend. Performance by Uma Thurman, and Luke Wilson, 20th Century Fox, 2006.

Story, Tim, et al. Barbershop. Performance by Ice Cube, and Anthony Anderson, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 2002.

Morrison, Toni. The Origin of Others. Harvard University Press. 2017.

Bibel, Sara. “TV Ratings Monday: ‘How I Met Your Mother’ Finale Hits High, ‘Bones’ & ‘The Tomorrow People’ Up, ‘The Voice’ Down”. TV by the Numbers. 1 Apr. 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

Schur, Michael. “Time Capsule.” Parks and Recreation. NBC. 3 Feb. 2011.

August 11, 2018

A Kiss of Shadows (Saturday Book Club)

One of the things I always wonder about a lot of the main characters in an urban fantasy series is why they choose to become private investigators, or at least some facsimile of the role. Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden is a “freelance wizard” who invariably gets either hired by the police to solve a murder or gets tangled up in some grand mystery only he can solve. Rob Thurman’s Cal and Niko (a half-demon and his street samurai Gypsy brother) quit a lucrative private security business to instead become private investigators. Laurell K. Hamilton’s best known character, Anita Blake, is a necromancer who does investigative and crime scene work freelance for the police. And Hamilton’s other established series character, Meredith Gentry, is the niece of Queen Mab of Faerie, and a genuine Faerie Princess, yet works as a private investigator in some dingy office in Los Angeles who (you guessed it) gets occasionally called in by the police to investigate a paranormal crime.

One of the things I always wonder about a lot of the main characters in an urban fantasy series is why they choose to become private investigators, or at least some facsimile of the role. Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden is a “freelance wizard” who invariably gets either hired by the police to solve a murder or gets tangled up in some grand mystery only he can solve. Rob Thurman’s Cal and Niko (a half-demon and his street samurai Gypsy brother) quit a lucrative private security business to instead become private investigators. Laurell K. Hamilton’s best known character, Anita Blake, is a necromancer who does investigative and crime scene work freelance for the police. And Hamilton’s other established series character, Meredith Gentry, is the niece of Queen Mab of Faerie, and a genuine Faerie Princess, yet works as a private investigator in some dingy office in Los Angeles who (you guessed it) gets occasionally called in by the police to investigate a paranormal crime.

Now I can understand this from the viewpoint of a writer. Looking at it mechanically, it makes sense to have the main character be some sort of investigator, because that’s how you set up a series. You could set up a long story arc and make it a trilogy, but then you’re pretty much done with that character. If you instead drag out those complicated character-deepening story arcs over, say, fifteen books or more, it can be a lot more attractive to a publisher considering that readers of urban fantasy as well as mysteries and the like prefer to stay with the same character, someone they’re familiar with. Making the character an investigator might seem like a throwback to noir and gumshoes like Sam Spade (which might even be part of the draw), but the point seems to be solving the mystery. The primary plot of the series book serves the purpose of mostly expanding the mythology of the created world in urban fantasy through its conflicts and antagonists, while the characters themselves are expanded and deepened by subplots that are resolved within the one story or over the course of several.

It all makes a measure of sense from a writer’s standpoint, but what about from a reader’s? How well justified is the character’s decision to be an investigator? This is one of the problems I had with Meredith Gentry, the primary character of A Kiss of Shadows. With Hamilton’s other character, Anita Blake, you get the sense that she’s an investigator because Necromancers are gently encouraged by the government to use their talents for investigative ends and aiding the police rather than raising zombies and terrorizing the countryside. Gentry on the other hand is a Faerie Princess who’s playing human to avoid responsibility. Considering that this is the first book in Gentry’s series, the pressure is on to set the rules and establish the character so that disbelief will remain firmly in suspension. I kept asking myself why, if she’s so intent on keeping a low profile, she took out an ad in the yellow pages for her business, and why she doesn’t have any problem with using her “talents” as one of the Fae in her investigations.

As a writer, I can definitely see Hamilton’s standard plot formula at work, only accelerated. When the Meredith Gentry series came out, the Anita Blake series was in full swing and its detractors were already clamoring that Hamilton’s writing had fallen from urban fantasy to soft-core vampire porn. Gentry starts off just as prudish as Anita Blake did, but instead of it taking a few books as it did with Blake, by the end of A Kiss of Shadows Gentry is practically wading through half-naked fae men. It’s as if for Hamilton the investigator role has become nothing more than the washing-machine repairman from countless low-budget pornos; a mantle to hang the minimal plot before it’s time for sex.

While I am planning on reusing my protagonist from Lightning Rod in a series, and probably using him in an investigative role, reading Hamilton’s writing if anything shows me what elements of her style I probably shouldn’t use. The primary reason protagonists in urban fantasy series tend to be investigators is that it always falls to them as they are, more often than not, the only ones with the talent necessary to solve the mystery. They could be doing it for money or justice, or just out of a sense of duty, or, as is sometimes the case, coercion. Its these factors that makes the investigator role more subtle, push it toward the original, let it be reinvented for the purposes of the story so that it will be the character instead of the character playing a role.

July 30, 2018

Four on the Floor: Part Twenty-Four

[image error]

Part Twenty-Four

“So, what, you’re just going to come home whenever you want? Fuck, girl, you need a shower!“

Tasha, clearly, is not too happy to see me. It’s a good sign that the police haven’t tracked down my phone though, at least, otherwise my stuff would’ve been on the curb. I have the feeling that a few scratcher tickets won’t do it this time.

“Yeah, uh… Could I get by you? Get that shower, change my clothes?”

She folds her arms, she’s more testy than usual today. “And while you’re at it, you can pack your sh-“ Tasha is staring directly behind me.

Right, Shan wanted to accompany me. Given the nervous sound she just made I’m guessing she sees him as a tall, well-dressed, and classically handsome black man. Which, now that I remember, is precisely her type.

While Tasha stammers her way to cautiously flirty small talk, I slip by and head to the bathroom, taking Pumpkin along with me. Once the shower’s running, I undress and get in, leaving Pumpkin on the sink.

Well, I get in after murmuring “cleanse”, considering that the shower needed it and I forgot to clean it over the weekend. I have never appreciated hot water this much in my life.

“A.J.? Did you bring a dragon here?!”

“Long story. Tired. Hungry. Need caffeine. Lots of stuff to tell you about.” For a minute I just stand under the hot water, closing my eyes, sore muscles announcing their soreness while the heat grants them some relief. Pumpkin, to his credit, remains quiet until I return from my reverie. Normally Tasha has a rule about maximum time in the shower, but with Shan out there I could probably be in here all night and she wouldn’t notice.

It’s a good thing, because it takes a while to tell Pumpkin everything.

“So, the Shadow Dancer, huh?”

“Don’t ask me.” I’m moving into shampooing my hair now, I really did need this. “That’s what Val called me and now everyone’s saying it.”

“And when did Shan swoop out of the sky?”

“After I went back to check on the body and found that bit of Sigil on the floor. Can’t believe I forgot my phone. I am so fucked.”

“Why?”

I peek my head out from behind the curtain. The water’s moving into warm territory. “Because I’m probably going to be arrested and blamed for that woman’s death?”

“You’re a sorcerer, A.J.”

“I’m not going to start throwing spells at people, Pumpkin, even if I did know how.”

“No, no. Not that. Sorcerers are generally forgotten by the world. They’re off the loom of Fate. Even your own mother would, um…” He trails off.

I slink back behind the curtain.

Even my own mother would forget me.

My father, too.

Pumpkin explained this to me when I first bound him into that skull, and went home to find my parents had no idea who I was. My room was now a makeup and design space, the photos around the house had an absence of me that no one noticed. They thought I was a spooky girl that might be a little too into the death and occult of it all, but were kind enough to me to let me crash for the night, because Goth is family. In their eyes I was probably a runaway. They were still the same people, just minus a daughter.

When the first zombies showed up outside their house, I was in denial, I did some things I’m not proud of to keep them away, which only made me look to them like a crazy person who hated homeless people. Regular people, humans, that is, know on some level that you’re Something Else, and after a week my parents were subtly nudging me out the door.

I try to see it from their perspective, I was just some girl who showed up on their doorstep and soon became in their eyes the reason you don’t take in strays, but from mine?

My parents didn’t love me anymore. All the logic in the world won’t dull the edge of that.

“A.J.? What I’m trying to say is that the police won’t come after you, because you don’t really exist. Not in the system. Any system. That phone will probably just come back as a burner with no prints.”

“Burner with no prints?” I chuckle, half-hearted. “You learn that from Diplomatic Immunity?”

“It’s more than just sex, you know, there are some thriller elements. Romance is a many-faceted genre.”

After a pause, I turn off the shower, sounds like they’re still talking out there, but I hush my tone while I brush my teeth, using “cleanse” on Tasha’s toothbrush, which spills over onto the sink, as well as the mirror.

“Don’t you usually need my help for that?”

“Yeah, I’m a little scared, Pumpkin, I’m doing stuff I’ve never done before. That thing with the shadows in the lake was creepy even for me, and I’m very concerned that this isn’t concerning me as much it would anyone else.”

There it is again, that subtle feeling that this is normal, that I’ll be okay, that it’ll all be okay.

“Abby? Would you rather feel all of it? Know how weird and wrong and not normal not only all of this is, but how not normal you are? And that you’ll never fix it, it’ll never go away, there’s no going back for you ever? Could you handle that every second of every day for the rest of your life? Could you really look at Les or any of those other zombies and be as cheerful and helpful when in your heart and soul you know that they’re not supposed to exist? Could you cast spells while suspecting the whole time that you’re crazy?”

“I would have preferred a choice in the matter, Pumpkin.”

“Blame your subconscious, I don’t know. You’re a sorcerer, Abby, because the moment came and deep down you wanted this. I saw you, and manifested, and instead of running away screaming to a therapist, you met my eyes and told me to fuck off and pushed me into a fucking Halloween decoration from a Dollar General. You wouldn’t trade this, Abby, not the magic or dragons or zombies or any of it for a normal life.”

I sigh, look in the mirror, then spit and rinse, and look again, wiping the steam off. “Fuck you.”

“I’m just saying what you already think, Abby.”

I take a deep breath.

“I know. But still, fuck you anyway.”

July 28, 2018

The Picture of Dorian Gray (Saturday Book Club)