Vaughn R. Demont's Blog, page 7

May 19, 2014

Justifying My English Degree: Heroes on the Periphery: The Dynamic Villains of Once Upon a Time

God, has it been two months? Apologies for neglecting the blog, been busy with end of the year grading of papers and the like, as well as dragging myself back to work on Breaking Ties, which is 3-4 chapters out from the finish line. In the meantime, my boyfriend and I have been rewatching this on Netflix, and having the sorts of conversations about the characters that are normal to fans, which inspired me to do a JMED on it. Some spoilers follow.

The Show: Once Upon a Time

The Show: Once Upon a Time

Creators: Edward Kitsis, Adam Horowitz

Principal Actors: Robert Carlyle, Lana Parilla, Jennifer Morrison, Ginnifer Goodwin, Josh Dallas

Synopsis: A woman with a troubled past is drawn to a New England town where fairy tales are to be believed.

The Critique:

At first glance, it’s pretty understandable why an urban fantasy writer would be into a show like this, even though it’s closer to suburban fantasy, a subgenre of UF populated with luminaries of the craft like Rachel Pollack, but the concept of the show, fairy tale characters in a modern world, has been touched on quite a few times, notably by Bill Willingham’s series of graphic novels Fables which has recently been adapted by Telltale Games, or even the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle Last Action Hero which follows the adventure of a movie character being brought into our world. The concept runs the common theme of characters, usually heroes, that previously lived in a world of clear-cut morality coming to grips with a world where thanks to moral ambiguity and other realities of our society, the bad guys can win.

Once Upon a Time runs a similar gamut at first blush: Regina (Parilla), the Evil Queen, brings practically every fairy tale character and Disney movie you can think of into our world, wipes their memories, and appoints herself Mayor of the town they all get stuck in, and proceeds to enjoy the spoils of her victory for the next 28 years, all thanks to a curse she bartered from Rumplestiltskin (Carlyle). It’s all done to give the biggest possible middle finger to Snow White (Goodwin) and Prince Charming (Dallas), but she’s eventually foiled by the daughter of her enemies, Emma Swan (Morrison), who breaks the curse. The show’s episodes run a standard formula of moving along the modern world’s plot while giving flashbacks to the time before the curse to flesh out the characters and reveal their motivations and reasons for their natures and action, as well as getting a chance to revise and inject some moral complexity into otherwise simple characters with simple motivations.

At first glance it would seem that Emma and Snow are the two central characters of the show, but respectfully, if you didn’t get this from the title of this essay, I disagree. I instead believe that Regina and Rumplestiltskin/Mr. Gold, are the two primary characters, whereas everyone else is on the periphery. As they are considered the villains, at least for the first season, they are the primary plot-movers whose actions prod the heroes into action, or more accurately reaction. Whenever a hero character seems to make a proactive decision, it’s soon revealed through dramatic irony that they’d been prodded along by either Regina or Gold all along, usually as pawns in the never-ending chess match between the two. Flashbacks which seek to deepen the peripheral characters often reveal that said depth is provided through interaction with (or more often manipulation by) Regina or Gold.

One of the things you’re taught either in high school or in early writing classes at college is the idea of static and dynamic characters. Static characters essentially remain the same throughout the story, no matter what happens, and more often than not want a return to the status quo. Dynamic characters often begin as static, but often some twist of fate or drastic event causes them to become a force of change. While I’m not going to be an apologist for Regina and Gold, they’ve both done some truly awful things in service to themselves, they’re the only real forces of change. Though some would argue that Emma is the true force of dynamism in season 1, as she breaks Regina’s curse that had held everyone in relative stasis for almost three decades, the plot is all too quick to reveal that it was all a machination of Gold to restore magic, and push along his own story to his own ends. And while Emma does show some dynamic qualities, as a skeptic she’s the slowest to change.

Gold and Regina, on the other hand, receive the most in-depth attention in both backstory flashbacks and modern plotlines. I believe this is due to our nature of wanting to understand villainy, why bad people do bad things, and how, if they can understand their motivations, we could perhaps rehabilitate them. As viewers, we can’t simply accept that Regina is the Evil Queen, we want to know how someone could get to the point where they’re willing to kill their own father, husband, and God knows how many others to spite one woman, and we soon learn that she was in fact a good person once in a strong relationship, and all too ready to be stepmom to a little girl who thought she was awesome that she thought was pretty awesome too, and then, as Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke told us was the cause for all villains, she had one Hell of a bad day. She took a look at the status quo and decided to change it to serve her needs. Selfish, that’s a given, but definitely dynamic as you watch her character fall farther and farther.

Gold is no different, his initial role as the town coward and its consequences pushing him into desperation to become the Dark One by force and in turn become the creepily giggling Faustian dealmaker that dominates much of the series, though unlike Regina, he has bouts of static development, broken mostly through Regina’s involvement. However, one could argue that they simply transition from bystander to villain and that would be the end of their dynamic trend, but I would still disagree.

As I stated earlier, we want to understand those that are capable of villainy so that, if we can nail down their motivations, we can possibly rehabilitate them, and rehabilitation is definitely a form of dynamism, though I doubt Gold and Regina would ever be fully rehabilitated outside of a series finales. Instead, in the aftermath of the curse on Storybrooke being broken, Gold and Regina remain the only two proactive characters, while everyone else generally fades into their previous fairy tale roles and attempt to resume their previous course, even if it’s in a new world. The denizens of Storybrooke seek only a return to their old world, a return to the status quo previously disrupted by Regina and Gold. Regina and Gold, on the other hand, now have to deal with both their magic returning as well as the consequences of their actions, with plenty of opportunities for redemptive action that sometimes they even take. The chances of Regina and Gold ever becoming heroes is low, but their characters are still changing, shifting, moving from villainy into the modern favorite of anti-heroes, committing unethical acts out of pure motivations, often to spare the heroic characters from dirtying their hands.

With this much attention on two villains as well as practically every plot being somehow connected to their motivation, rehabilitation, or moral stumble, the heroic characters move a little further to the edge of the spotlight. They might get to remain the moral center, but the dynamic center belongs to the villains.

March 11, 2014

A Few More Tips on Being a Writer

So you still want to be a writer. Normally I’d wonder why the person who’s supposed to shake you out of making bad life decisions is apparently asleep at the wheel, but I suppose there are a few of us who have to write or we’ll surely go insane. I’ve gone into this before, but there are a few additional things I’ve learned over the years that I feel like putting out there. This is all based on experience, so please have a complimentary pound of salt to take it with.

1. Don’t Be Afraid of Your Comfort Zone

Ah, the Comfort Zone. When I was in grad school, for the most part the Comfort Zone was something that I was taught would likely burn my flesh should I ever approach it. It’s the idea that left to your own devices, you’ll only watch TV and read Cracked articles and never write anything that’s “of worth”. It’s mostly a question of Quality, and I use the capital Q there because trying to define it is an impossible task and actually drove a guy insane. Most of us read literary fiction because there’s a grade in it for us, or because it’s handed to us by teachers who hope they can keep slapping on the hallowed pages of vaunted masters of their craft, and eventually we’ll emerge from the chrysalis ready to pen The Great American Novel.

Most of the time we just go for the grade, because required reading will make any text boring as hell.

The thing is that I’d been reading nothing but LitFic since junior high and when I did read genre fiction it was usually in my free-time to convince myself that reading and firing up the imagination could actually be fun. I had all these ideas about the structure and mechanics that made the “fun” books work to the point where I could call the plot twists three or four chapters in advance, but when I got to grad school, and actually had the opportunity to research it in earnest, I generally got shot down because “I needed to move outside my Comfort Zone”. Granted, this changed once I got a better advisor, but until that point, I kept being told that my Comfort Zone was the last place I wanted to be, even though it was what I wanted to write and study.

So this is my advice: If you write bisexual vampire stories and you love bisexual vampire stories, then by God read bisexual vampire stories, watch the movies, check out the comics, listen to music that was used in the soundtracks, because if you’re reading Proust, you’re going to miss the unspoken rules. And trust me, if you break those rules your readers (and the reviewers) will let you know. The rules of the genre you write in are set by countless authors, screenwriters, graphic artists, and readers, and you’ve got to keep up on those rules because they vary. Don’t expect to be the writer who shatters all conventions and rewrites the rulebook. You’ll be allowed a little leeway, but you’ll know when you abuse it. Trust me. High School is over. College is over. No more term papers to write. The Comfort Zone is your friend now.

2. Give In to the Shippers

One of the things that gets readers going is a little bit of genre-blending, it’s how you get new readers in and keep current readers on their toes. One of the unspoken rules of genre fiction is that if you’re writing a series, there has to be an Inevitable Couple. Shippers are out there, and even if you’re not writing romance, you have to be prepared not only for the subplot writing, but also making sure you follow the unspoken rules of that genre, which is knowing how to stall the romance while not frustrating the reader. I’ve received e-mails from readers about Community Service that want to hate Ozzie, because he’s standing between the James and Spence pairing, but at the same time feel they can’t hate him because he’s a nice guy and treats James right. I learned that trope from watching Rom-Coms like Sleepless in Seattle and You’ve Got Mail, and more often than not it doesn’t end well for the Nice Guy/Girl. Sitcoms can stretch an Inevitable Couple for a few seasons, always delaying with the On Again/Off Again, Right People/Wrong Time, and countless other tropes and tricks to make it seem soooooo close to possible. Look how long Harry and Karin have been stretched in The Dresden Files. Even Joss Whedon lets characters be in a happy relationship for five minutes every now and then (usually right before he kills them, but still!).

The point is, if you have have a main character, and have any sort of character of the protagonist’s preferred gender, people are going to start matchmaking, and you have to be aware of that, and be willing to play along no matter what genre you’re working in.

3. You Will Trip Up When Trying to Describe Your Book

I call it “The Basicallies”. Go to any social gathering, and if it comes out that you’re a writer, after being asked the inevitable “Have you written anything I’d have heard of?” (Because yeah, unless you’re an NYT bestseller, the answer will always be no, and sometimes even when you’re an NYT bestseller), you’ll be asked, “What’s it about?”

God, I always dread that question, and if you write genre fiction? So will you. It’s especially bad if you’re a sci-fi/fantasy writer, because eventually you’re going to reach the point where you have to bring out the weird, and to keep from embarrassing yourself, you’ll do anything to avoid the weird. So, “the basicallies” come out in full force. Seriously, try to explain your book to someone not familiar with the genre, in an actual face-to-face conversation and see how many times you use “basically”, “essentially”, “at its core”, and any other number of boil-it-down terms as you stumble your way to revealing the dreaded “protagonist is an IRS auditor that’s a werewolf dating a witch that does her rituals to KMFDM” detail that will bring the dreaded, “Oh.” (And now I’ll bet there’s someone out there that’ll be like, “Damn, I want to write that now.” I want credit in your acknowledgements.)

There’s no real way around it, but at least you know now that you’re not alone.

4. Distraction Is Your Necessary Frenemy

Daily wordcount’s funny thing. It’s supposed to be the measure of how committed you are as a writer, how much you’re producing compared to those people who aren’t measuring up and putting out at least one novel per year, usually two. When you’re writing, you’ll find that distraction is the enemy, the biggest offender being the social media that we consider a necessary evil. With movies on demand and god knows how many sites to dunk your head in to catch up on serialized dramatic TV, it’s a wonder we get anything done at all. The thing is that we need it, and I’m not ashamed to say that. I won’t go into how many times I’ve watched Ugly Betty or booted up The Sims or gone through yet another full playthrough of the Mass Effect Trilogy because I’m stuck and need to soak my head in some media to rejuvenate my mind. The trick is knowing when your brain needs the rest and when you’re just stalling. Case in point, this blog entry is over 1500 words in total, and some would say that’s 1500 words that could easily have gone into the next book and get me that much closer to completion. But would it really? When I sit down I have no idea how much writing is going to come out of me that day, no matter how much caffeine I’ve ingested or how much Oceanlab and BT is playing in the background or how many Skittles are in easy reach. Mostly I sit down with a plan to finish a scene, or get a chapter started, and if more comes out, great. Some days I write 500 words, sometimes it’s 2500, and some days it’s nothing. (This is usually when I’m grading papers or working on lesson plans. I’ll do a blog entry on teaching and writing at some other point that isn’t the usual lamenting you see so often.)

Distraction is a necessary evil, because sometimes when you’re stuck stressing about being stuck is only going to make you more stuck. I’m not a fan of the idea of “waiting for the muse”, but guys, sometimes the muse wants to just kick back and catch up on Arrow and wonder if Olicity is ever going to really happen or if their current theory on the ending of How I Met Your Mother is the right one and praying that they’re wrong. Sometimes it can’t be helped, and stressing about it will only make you want to strangle yourself, and as Jim Butcher said, “Don’t strangle yourself.”

February 25, 2014

Vaughn’s Gay Words of the Day

In a bit of a silly mood today, mostly driven there by my students, so here are some terms you might like to know:

Gay Guy 1. n. A homosexual man that falls on the masculine end of the scale, but not so much as to be considered butch. Often interested in professional sports, violent media and popular music, but oblivious to most media that is stereotyped as gay by popular culture. Often considered to be bisexual or straight unless directly asked about sexuality. Sometimes also referred to as a gay bro.

Fag Hag 1. n. A woman, usually heterosexual, who provides social, emotional, and moral support to a homosexual man or group of homosexual men in a social setting. Defined by comedienne Margaret Cho as “the cornerstone of the gay community.” 2. n. A term of endearment often applied to a close female friend of a homosexual man. 3. n. The woman who gets you off your ass and out of the damned house because, God, what, are you just going to sit around all day waiting on him to call? Put some good clothes on ’cause we’re going out… After you’ve taken a shower, ’cause damn.

Fag Stag 1.n. A heterosexual man who provides social, emotional and moral support to a homosexual man, though often of the masculine variety. 2. n. The straight male friend who still hangs out with you, even when you want to bring your boyfriend.

Haguette 1.n. A younger woman, usually the daughter or younger sister of a fag hag, who is also supportive of homosexual men. 2. A term of endearment for a fag hag, e.g. “My little haguette.”

Homophony 1. n. A straight man who acts gay in order to sleep with women. (Please see Bloodhound Gang’s “I Wish I Was Queer So I Could Get Chicks” for further reference.) 2. A straight man who acts gay in order to get ahead in career paths that “traditionally favor gay men”. (See Ugly Betty or That Episode Of Will & Grace That Had Matt Damon That One Time, I Think He Said Debra Messing Had A Rockin’ Ass Or Something? for further reference.)

Pink Team Groupie 1. n. A straight man who hangs out with gay men in order to sleep with women, usually at a gay club or bar. 2. n. A straight man that gay men help to meet women through accentuating their “open-mindedness”.

February 19, 2014

Justifying My English Degree: Perspective and Moral Ambiguity in Assassin’s Creed 4

Since I finally broke out of movies with going to TV, this is one that’s been rattling around in my head for a bit since I finished the game.

THE GAME: Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag

THE GAME: Assassin’s Creed IV: Black Flag

PUBLISHER: Ubisoft Montreal, 2013

PRINCIPAL ACTORS: Matt Ryan, EJ Schneider, Danny Wallace

SYNOPSIS: In the not so distant future, a new employee of a video game developer delves into the life of a little known Welsh pirate of the 18th century, and promptly finds himself caught between two long warring groups.

Warning: Some spoilers for AC4 follow

THE CRITIQUE: Perspective is a rudimentary part of storytelling. Depending on the POV that’s being employed, perspective can vary, but it’s more often than not the perspective of the rookie, the new guy, the fresh hire, the uninitiated. It’s an easy trick that’s used to make sure that the exposition at least appears organic, because it would make sense to tell a new guy, and by proxy, the reader, how things work. While the player is thrown into the thick of things when AC4 first kicks off, it’s soon revealed that it was all a simple stress test for new employees of Abstergo Entertainment, a gaming developer about to release a killer app and only needs the right data to nail down a solid launch, data that the player will be gathering be delving into the life of Edward Kenway, a Welsh privateer turned pirate and reluctant assassin.

From that point on, you’re largely seeing the world through Edward’s eyes and, mostly through his philosophy of social freedom, getting drunk, and getting paid. The conflict between the series’ core factions, the titular Assassins and the Templars, largely falls to the background, only addressed when both Edward and the player can tear themselves away from sailing around the Caribbean, pillaging cargo, and getting all manner of sea shanties stuck in their heads. It could be argued that this is the whole point of the exercise, considering that the player’s character is working, though unbeknownst to him, for the Templars in the modern day section, and it’s simply serving the purpose of downplaying the conflict between the groups so that the public can concentrate more on chasing simple pleasures, but that point, I believe, only sheds light on why I’m writing about perspective in the first place.

The first five Assassin’s Creed games (Assassin’s Creed, Assassin’s Creed II, Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood, Assassin’s Creed: Revelations, and Assassin’s Creed III), all have one thing in common: they’re from the perspective of the Assassins. While obviously all of the games in the AC series features Assassins, the modern day sections have always been from their perspective, using player surrogate Desmond Miles as the series’ core character. There are some obvious differences between Desmond and the AC4 modern character, referred to hereafter as the Employee. Desmond spends most of his time on the run with his team (though taking plenty of breaks for selfies), doing their past-life delving from rundown buildings, warehouses, and caves, while the Employee gets an office space with access to a coffee bar and a friggin’ aquarium elevator.

It’s not just environment, though. Desmond was raised by the Assassins, his entire paradigm shaped by their philosophies, training, and indoctrination. As a result, the player only sees the conflict from that perspective: Assassins good, Templars bad, and daddy issues for everyone. Considering that a large number of players have played the entirety of the series, it’s understandable that there would be some overlap when coming into Assassin’s Creed 4 and only given the blank slate Employee to work with. Characters like the Employee are created solely for self-insertion, after all, but it’s likely that Ubisoft assumed players would simply apply the same perspective to AC4 that they’d been carrying through the last 5 games, not only to the modern character, but also to Edward Kenway as well.

But stepping back from that, if a player jumped in fresh into the Employee, having never played the series before, they’d likely see both sides as dicks.

Don’t get me wrong, there’s plenty to not like about the Templars in this game. “Google is evil” allegory aside, the Employee is still working for a subsidiary of a company that “disappears” people on a regular basis, and has autopsy videos on their servers of the “gracious donor” that’s making your memory-jaunts to the Bahamas possible. While plenty could easily point out that the modern Assassins in the game, Shaun and Rebecca, who return from the previous games in the series, aren’t evil, they’re just a little stupid and naive (Seriously? A bad bottle job and a baseball cap are really going to hide you when you were all constantly taking selfies on cell phones that your enemies now have?), the point of perspective with them is that only players who’ve gone through the series would reasonably side with them, already having been indoctrinated by their time with Desmond. For the player who didn’t, or who can divorce themselves from the previous experience, the Employee isn’t an Assassin in the making, or a Templar for that matter: he’s a pawn being slowly nudged by both sides into checkmate.

This is best underlined by the final scenes, where the Employee is trapped and pinned down by a psychotic Assassin that Shaun and Rebecca let loose on him. When the Employee is saved, it’s a Templar who asks if you’re all right, not an Assassin. In fact, the Assassin’s only offer a “Whoops! Never thought he’d try to kill you. Our bad! But you’re going to keep feeding us confidential data, right?”, while the Templars offer the Employee a generous bonus package plus hazard pay. Sure, it’s only money, but at least it’s something. It’s not enough to sell you on either side, in fact, with that virgin perspective, it’s shown to the player that both sides are both right and wrong, that both sides use morally ambiguous methods, it’s just that one side is better funded. Without Desmond’s story fresh in the player’s mind, while it’s still hard to cheer for the Templars, the Assassins lose a lot of their moral high ground, which is likely the reason for the credits scene: Edward Kenway sailing off into the horizon, leaving both sides behind. His point is that he screwed up, so maybe he’s not ready for the Assassins yet. In modern times, I wish there was a similar option for the Employee, to walk out the front door to hop a plane to anywhere, because the Assassins screwed up, and maybe they need to fix that before their next move. Because let’s face it, when your perspective is revealed to be that of a pawn, with both sides pushing, sometimes the choice is to leave the board, give the finger, and walk away.

January 20, 2014

Justifying My English Degree: The Strange Case of Shamy in “The Big Bang Theory”

The Show: The Big Bang Theory

The Show: The Big Bang Theory

Principal Actors: Jim Parsons, Mayim Bialik, Johnny Galecki, Kaley Cuoco

The Characters: Dr. Sheldon Cooper, B.S., M.S., M.A., Ph.D., Sc. D.A genius-level yet socially inept theoretical physicist that forms the core of the social circle that comprises the cast of The Big Bang Theory.

The Characters: Dr. Sheldon Cooper, B.S., M.S., M.A., Ph.D., Sc. D.A genius-level yet socially inept theoretical physicist that forms the core of the social circle that comprises the cast of The Big Bang Theory.

Dr. Amy Farrah Fowler, Ph.D. A highly intelligent and also social inept neuroscientist who serves as the most recent member of the BBT circle.

The Critique:

I often wonder how I’d react if I met Dr. Cooper in real life. Chances are we’d bump into each other at a Mensa meeting, and he’d be one of those guys who only goes to ridicule the guest speaker and call out every one of his inaccuracies, while I’d be the guy who’s there for the buffet table and free coffee. Despite our proud membership in geek culture, Dr. Cooper and I would find ourselves on opposite sides of the line. He’s hard science, I’m one of those people who studied the humanities. He went to prestigious universities for his studies, and I went to a grad school that until recently had a proud tradition of an annual co-ed nude volleyball game. He’d dismiss me as wasted potential and I’d probably roll my eyes and wonder how someone ended up with screwed up priorities. Also, I’d inform him that it’s “wasted potential” like mine that supplies him with his precious comic books.

While Sheldon Cooper’s social graces are often attributed to Asperger’s, which even Jim Parsons, the actor who portrays Sheldon, claims inspires his performance, there’s another aspect to Sheldon that I often see bandied about, namely that Sheldon is asexual, and that he’s being ruined by the writers who are forcing him into “a binary gender relationship” with a bisexual woman in order to enforce societal relationship mores on them and ease the concerns of the traditional viewer.

I respectfully disagree.

Now, even though asexuality and bisexuality do catch some flack, especially from the gay community (often derogatorily referred to as “closet-clingers” and “half-gay”), I wholeheartedly believe that yes, there are people who simply don’t seek sexual relationships with people, as well as there being people who prefer both.

Dr. Amy Farrah Fowler, played by Mayim Bialik, has been thought of by some fans to be bisexual, primarily through her involvement with Sheldon and her apparently infatuation with Penny, played by Kaley Cuoco. Originally, Amy was almost an exact duplicate of Sheldon, being aloof, superior, highly intelligent, and lacking humility. However, as the series continued on, she began to open up, forge friendships with other women, and take her place in the social circle that comprises the show. In my opinion, Amy represents an accelerated version of what’s essentially happening to Sheldon throughout the series. Much like Sheldon, Amy’s past includes being ostracized by her peers due to her intelligence and social ineptitude, though her educational advancement wasn’t as pronounced as Sheldon’s. This, I believe, stems from a throwaway gag where Amy mentions that she’d been ostracized by women through elementary, junior high, senior high, undergrad, graduate school, and doctoral work. While that’s a long period of seeing other women as primarily traitorous and mocking, it also underlines Amy’s long exposure to social dynamics, and her eagerness to form bonds with other women however many attempts it takes. As the series progresses, it displays Amy not emerging from her shell per se, but rather feeling comfortable enough to be herself, though her overreaching is often played up for laughs. It’s that overreaching that, I believe, leads to the fan’s suspicions that Amy may be bisexual. While I do fully believe that people can be bisexual, I also believe that there are different “types” of bisexuality much as there are different “types” of homosexuality and heterosexuality. Personally, I would classify Amy as a male-biased bisexual woman. What this means is that while she does find other women sexually attractive, and would engage in relations with women, she would rather pursue a long term relationship with a man instead of a woman. Or, at the very least, she’s heterosexual with bi-curious tendencies, but I’d lean more toward fully bisexual. Still, bisexual people can maintain long term relationships with members of the opposite sex, or the same sex, hence being bisexual.

Dr. Amy Farrah Fowler, played by Mayim Bialik, has been thought of by some fans to be bisexual, primarily through her involvement with Sheldon and her apparently infatuation with Penny, played by Kaley Cuoco. Originally, Amy was almost an exact duplicate of Sheldon, being aloof, superior, highly intelligent, and lacking humility. However, as the series continued on, she began to open up, forge friendships with other women, and take her place in the social circle that comprises the show. In my opinion, Amy represents an accelerated version of what’s essentially happening to Sheldon throughout the series. Much like Sheldon, Amy’s past includes being ostracized by her peers due to her intelligence and social ineptitude, though her educational advancement wasn’t as pronounced as Sheldon’s. This, I believe, stems from a throwaway gag where Amy mentions that she’d been ostracized by women through elementary, junior high, senior high, undergrad, graduate school, and doctoral work. While that’s a long period of seeing other women as primarily traitorous and mocking, it also underlines Amy’s long exposure to social dynamics, and her eagerness to form bonds with other women however many attempts it takes. As the series progresses, it displays Amy not emerging from her shell per se, but rather feeling comfortable enough to be herself, though her overreaching is often played up for laughs. It’s that overreaching that, I believe, leads to the fan’s suspicions that Amy may be bisexual. While I do fully believe that people can be bisexual, I also believe that there are different “types” of bisexuality much as there are different “types” of homosexuality and heterosexuality. Personally, I would classify Amy as a male-biased bisexual woman. What this means is that while she does find other women sexually attractive, and would engage in relations with women, she would rather pursue a long term relationship with a man instead of a woman. Or, at the very least, she’s heterosexual with bi-curious tendencies, but I’d lean more toward fully bisexual. Still, bisexual people can maintain long term relationships with members of the opposite sex, or the same sex, hence being bisexual.

Sheldon, on the other hand, while still reportedly a virgin in the lore of the show, and not having shown any interest in engaging in sexual relations, and being portrayed by an openly gay actor, I do not believe is asexual for one primary reason: lack of normative socialization. It’s well-established in the lore that Sheldon not only achieved a Ph.D at 16, but has several degrees by his mid-20s, which implies a heavy focus on education and his studies, with most of his socialization with other children being in the form of bullying or ridicule. It’s Sheldon’s immaturity and selfishness that implies a lack of psychological as well as psychosexual development. It’s established in the series that Sheldon’s father was an alcoholic while his mother is a deeply religious woman. In fact, the majority of influence in his childhood came from women, namely his mother and “Meemaw”, who lavished him with attention while his father died from heart disease. That combined with his selfishness (which was never corrected, apparently) and high intelligence paired with a superiority complex could explain Sheldon’s complete lack of tact social skills that most people learn in the gauntlet that is public education. Also, it’s important to remember that when most guys are figuring out what their dangly bits are for, all of Sheldon’s attention was on quantum physics while he went for his Ph.D.

It’s Sheldon’s development over the course of the series that, in my opinion, provides the foundation of the narrative. This is the story of Sheldon learning how to be a person, not just a mind to someday upload into a robot or computer network, and how he met the woman who would help him get there. The Sheldon of season 7 is markedly different from the Dr. Cooper of the pilot, having gone through over seven years of socialization with people he wouldn’t have given a second look at. Throughout his relationship with Amy, we see the slow process of a man reviving his psychosexual development, in particular in season 6, where after being mocked by their friends during a session of Dungeons and Dragons, and Sheldon’s character is forced to fall in love with Amy’s character. To Amy, her lack of progress with Sheldon is underlined and laughed at, and understandably, it’s humiliating for her. But there’s an important moment in their relationship, when he describes in fumbling terms how his character would seduce hers. It’s clearly the erotic fantasy of a virgin, but it’s a turning point in their relationship. When they began their relationship, Sheldon termed it as “intellectual”, a relationship of minds. In that scene, Amy, as well as the audience, is shown that Sheldon is beginning to see his girlfriend not as just a mind, but as a woman as well, and a woman that he does find physically attractive as well as intellectually.

While I can see why fans would view Sheldon as asexual, I don’t agree with it. I believe that asexuality is simply the way that a person is, not that it’s a choice or the result of social or psychosexual retardation. That would imply that if you’re asexual, something or someone screwed you up badly and you can, somehow, be “fixed”, much as some still believe about homosexuality and bisexuality. Instead, it’s easier for me to believe that forgoing social experience can having a lasting effect on anyone, and that Dr. Cooper provides an excellent example of this.

January 6, 2014

Justifying My English Degree: For the Love of the Con: “Now You See Me” and Our Desire to Be Tricked

THE TRAILER:

THE FILM: Now You See Me, Summit Entertainment, 2013

THE FILM: Now You See Me, Summit Entertainment, 2013

PRINCIPAL ACTORS: Jesse Eisenberg, Mark Ruffalo, Morgan Freeman, Melanie Laurent

TAGLINE: The closer you look, the less you’ll see.

SYNOPSIS: An FBI agent and an Interpol detective track a team of illusionists who pull off bank heists during their performances and reward their audiences with the money.

THE CRITIQUE:

The closer you look, the less you’ll see. That’s the line that’s bandied about constantly in the 2013 film Now You See Me, or as it was shorthanded (and probably pitched), “Ocean’s 11 with magicians”. Heist movies and television showcasing con artists are generally well received by Americans, the people who steal exorbitant amounts of money without ever lifting a gun or causing physical harm, instead getting by on persuasion and remarkable charm. Seeing as the crew of Now You See Me succeeds in heists of 3 million euros, $140 million, and finally half a billion dollars, yet never keep a cent for themselves and distribute the wealth to the masses, it’s understandable why the film follows the proper trope rules of a modern heist movie. I say modern because the rules have changed in the last few decades in order to make the suave and debonair thieves more likable to the audience. To provide a quick example, the Pierce Brosnan driven remake of The Thomas Crown Affair significantly alters the thefts, having Thomas forgo the guns of the original and instead relying purely on misdirection and distraction, turning the crime from violent to elegant.

However, Now You See Me offers magicians as its protagonists, sliding them into the Robin Hood role, though, from a writer’s standpoint, I never knew one way or the other if they truly believed the altruistic show they were putting on, or were just following the script for the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. What did stick out for me, though, was a short character development scene on a plane from Vegas to New Orleans, meant to poke fun at the FBI and Interpol agents (Dylan and Alma) chasing the crew, forced to fly coach while the magicians are on a private jet exchanging witty banter.

In this scene, Dylan (Mark Ruffalo) and Alma (Melanie Laurent) kill time on the long flight while Alma attempts to learn a simple card trick:

Alma: Is this your card?

Dylan: No, my card is sitting over there in that guy’s lap. (ALMA facepalms while DYLAN retrieves the card) Nice shuffle.

Alma: Is it magicians, in general, that you have a problem with? Or specifically these guys?

Dylan: (pouring drink) I could care less about magicians in general. What I hate is people who exploit other people.

Alma: Exploit them how? (offers him the cards) Pick again.

Dylan: (taking a card) By taking advantage of their weaknesses. Their need to believe in something unexplainable in order to make their lives more bearable. (Looks at card, puts it back in the deck)

Alma: I see it as a strength. My life is happier when I believe that. (Puts down the King of Diamonds) Is this your card?

Dylan: (smiling slightly) Yeah.

Alma: (grinning) Yeah?

Dylan (smiling a bit bigger) Yeah.

Alma: (grinning widely now) Cool! (sees DYLAN’S smile, points at it) That smile on your face. Is it real?

Dylan: (shrugs) Maybe.

Alma: So let me ask you, Mr. Detective Man. Do you feel exploited? Or did you maybe have a tiny, tiny bit of fun?

Dylan: (doesn’t answer, and hides his smile by taking a drink)

While it’s a little difficult to not look at that scene and say “writer-ly”, at the same time I feel it addressed the concerns the writers felt the film was going to receive critically. Heist and con movies, after all, are generally a ride, and more often than not don’t have much substance to them. Any conflict between members of the crew is more often than not simply another layer of the con to better draw in the mark, the plot needing to focus on the “behind the scenes” leading up to the big trick, and then having to pull the curtain and reveal how it was done.

In the film, Thaddeus (Morgan Freeman), a professional “magic debunker” remarks that over 2 million people had gone to see magic shows, but 5 million people had downloaded his videos explaining how the tricks were done. This is one of the reasons, I believe that movies like Ocean’s 11, Now You See Me, and TV shows like Leverage have a following: They’re essentially magic shows where you get to have your cake and eat it too. You get to be amazed by the con and the spectacle and illusion, and then almost immediately find out how it was done.

There’s no doubt that Dylan, in that scene, likely knows exactly how that simple card trick works, but that slight smile is still genuine. When we go to magic shows, or heist movies, we know exactly what we’re getting into, that it’s not actually magic, and that nothing is immutable until the summation plays out, the curtain falls, and the credits roll. The movies are meant to be a ride, but that scene is an answer to those who deride it for lacking substance, or who call it out on various errors, or, well, look closer, because the closer they look, the less they see. As said near the end of the film, “All we wanted was to bring the world to a magic show,” and magic shows are mostly meant to be entertaining, to allow the audience to have a “tiny, tiny bit of fun.” It’s that promise of amazement, wonder, and well, fun, that keeps us coming back, for that split second where we consider that the illusion might be real, and that all things are truly possible, and whether or not we can see that as a weakness, or a strength.

January 5, 2014

Commentary: On the Emotional Investment of Fandoms

I’m not into (Insert Popular Media Here).

The above statement is something that I dread saying, not because I don’t mean it, but because it can be a dangerous thing to say. Essentially, it means that I don’t play into a like/dislike duality, and most people would agree that for most things, just because you don’t like something, doesn’t mean that you dislike it, or rather, that you hate it. It just means you’re not into it, and if offered it, you’d politely turn it down and ask for other options.

Unless, of course, you’re dealing with a fandom.

Fandoms tend to subscribe to the “with us or against us” absolute in regards to whatever media they champion. Often they have a quirky name for themselves, a codex of in-jokes, formal terms, and vulgar argot, and usually a plethora of official merch and fan-made items. Also, you’ll usually be able to pick them out on your social media feeds because they won’t shut the hell up about it.

Fandoms are interesting because of emotional investment, they seem to push themselves past a general acceptance of opinions on a subject into a black and white mentality in regards to the object of their adoration. Or, better put, in regards to the object of their affection, you can only love or hate. Love it and you’ll be welcomed into the fold, though you’ll likely be categorized and relegated by your knowledge of the subject and overall devotion to it. Hate it, and you’ll be dismissed as a hater, or seen as the enemy. Haters get to have their cake as well, as the loving side of the fandom is often a never-ending generator of material for memes and mocking. Even haters often have a working knowledge of the subject to better deliver targeted barbs against the fandom.

But the indifferent, ah, the indifferent, seem to infuriate the fandom more than anyone, and I believe that it comes down to emotional investment. To analogize, video game consoles are expensive, and if you want next-gen, you’re going to have to shell out $300-500 just for the base system. For most people, you can only get one system unless you’re doing well and can get the other ones. As a result, there’s always going to be part of you that wonders if you picked the wrong console, so a console “fanboy” will defend his choice to the point of zealotry for fear that he might have to admit he wasted his time and money. Anyone who wants to see the effects of emotional overinvestment need only look at the Xbox One unveiling and the subsequent fallout on the internet.

When someone hates your chosen object of fandom, you can simply dismiss them as a hater, yes, but the important thing is that you recognize that they have emotional investment in the same thing you love. The indifferent, on the other hand, have zero or negligible emotional investment, and that reflects on the fan’s overinvestment, it serves as a reminder that there are a vast number of people who honestly don’t care about their beloved media or object, and frankly sometimes find them annoying. So, more often than not, the indifferent are awkwardly shoved into the “hater” box, even though they don’t give enough of a damn to hate it. In fact, while the indifferent don’t hate the object of fandom, they often end up hating the fans themselves.

When I was in high school, I saw a bumper sticker that read, “I don’t have a problem with Jesus, he sounds like an okay guy. His fan club, on the other hand…” It’s one of the things I try to cling to: don’t judge something by the people who like it.

An example. I’m not into Doctor Who, nor am I into Torchwood (sorry, you need more than a gay actor to draw me in), but I’m terrified of mentioning that on my Facebook feed, because Whovians are scary in that regard. Tell a Doctor Who fan that you’re honestly not into the show, and they’ll look at you like you just grew a second head. Clearly, you haven’t seen the right episode, the right Doctor, the right Companion, the right Christmas Special, or maybe you need to be reminded for the fiftieth time that John Barrowman is gay (he’s okay in Arrow, I guess, but if I’m going to squee over a gay actor, I’ll go with Matt Bomer, thanks). A Whovian can’t understand how someone can “not be into” the show. Haters, they get, and dismiss, but the indifferent are treated like lost lambs that must be guided back to the herd. I *have* tried to watch Doctor Who, I’ve seen Tom Baker, Chris Eccleston, David Tennant, Matt Smith, I’ve been shown Sarah Jane and Rose and a bunch of other people, I’ve been shown Daleks and Cybermen and Weeping Angels and I’ve been fully aware that I’ve been watched while I was watching, and every time, I’m just “ehh.” One friend, I guarantee, will read this entry, roll his eyes, and say “There he goes, hating on the Doctor again”, even though I don’t hate Doctor Who. Honestly, I just don’t care about the show. The Doctor, I guess, seems like an okay guy. His fan club, on the other hand…

December 30, 2013

An Open Letter To Jim Butcher

Mr. Butcher:

Sorry, I in no way feel comfortable calling you Jim. You probably don’t remember me but you commented on my old blog once when I openly pondered about your process when writing Harry Dresden. I didn’t expect a response from you, but I got a paragraph back with good advice, summed up with “So what I’m trying to say is: don’t strangle yourself.” It’s good advice and I’ve tried to stick to it. I’m starting with this because this is an entry that’s taken a while for me to work up the bravery to write. I don’t expect a response, but once I hit that “Publish” button it’s pretty much out there and we all know the internet is forever, or at least until long after we’re dead.

So here goes.

Apology not accepted.

God, that was hard to write. I mean, you’re Jim Butcher. Fame aside, you’re my primary influence. You’re the reason I write urban fantasy, I’ve read all of the Dresden Files, I even wrote my master’s thesis partially on your work. I’ll admit that my discovery of you was a little less than innocent, as I started reading your work to try to get into a guy’s pants, but after I was five books in I forgot about that guy anyway. Hell, to this day I still don’t remember his name, but I remember going home for Thanksgiving break and starting on Storm Front and knowing that this was the kind of writing I wanted to do. So I don’t want you to think in any way that I hate you now or that I’ll be spreading idiotic vitriol all over the internet.

But yeah, this is about Cold Days. And the Magic Hedge scene. I’ll say this first as a writer: God, that scene was so forced. You know the part I’m talking about. And we both know why you wrote it.

Okay, my reaction probably wasn’t like other gay readers who might’ve approached you at cons about it. We’re talking about the scene that started all this, by the way, when Harry went into Thomas’s apartment and acted like a flaming queen to throw off the cops? Yeah, that one. My reaction? “What… what the… Oh god… Really, Harry? Really? That’s how you see us? Really?” I wasn’t mad, just… disappointed. I want to believe that Harry knows that all gays are not flouncing flitty fey folk, and that just because Thomas is playing up the gay hairdresser stereotype to get his fix, it doesn’t mean that if Thomas had a lover said boy toy would be working a double bill at a drag show. Thing is, the series is first person, we’re in Harry’s head, and a throwaway sentence about Harry thinking he’ll play up an inaccurate stereotype to throw them off the scent would’ve prevented all of this.

But to be honest, Mr. Butcher, I’d pretty much forgotten about it until Cold Days.

And then I get almost a full page of Harry telling me why he’s totally cool with gay people. I get it. This was killing two birds with one stone. Harry makes it known to the reader that he’s not a homophobe, and in turn you do the same. It was an apology, of sorts. I think I covered my feelings on that apology.

But here’s the thing, I don’t think you’re a homophobe. I think you’re a straight guy. Straight guys really don’t know what it’s like to be gay guys, because, well, you’re straight. You know how to be friends with us, that’s for certain, and for a geeky or nerdy gay guy, you’d make a hell of a fag stag, I’m sure. But maybe it’s media, maybe it’s geography, maybe it’s an age thing, but straight guys still tend to see us in certain ways. And as a gay guy, it’s occasionally my job to take a straight guy to the curb, sit him down, and tell him how that could’ve gone better.

So I’m going to tell you a little story. When I was in undergrad I took an English course called “Theories of Diverse Sexuality”, but everyone just called it Queer Theory. The professor was Dr. Curtin, and the day I remember best in that class was a day she showed us photos from the Maplethorpe exhibit, particularly one that was a black man in a cheap suit with his penis hanging out, which was the only indicator of his race. The point of the image, we were told at least, is that black men for the longest time were seen as simply that: walking penises, threats to the masculinity of straight white men. I bring this up because it’s one of the things that gay men and black men have in common: we’re viewed as lecherous men who only think about what’s going to get us laid first and everything else second.

So, knowing that, I’m hoping you’re beginning to see the issue with Harry saying he’s totally okay with gay people at the Magic Hedge. Mr. Butcher, I might also add this is the first time gay men have ever appeared on your stage, was in that apology scene, in a place gay men hook up for anonymous and often unprotected sex. Jim? Really? That’s how you see us still? There are a dozen ways you could’ve done that scene. He could’ve done it at a public garden that’s not used for hooking up, or a greenhouse, or maybe a lakeshore, or anywhere else, and perhaps two guys dressed in plainclothes walk by hand in hand, and the Summer Queen sees and ask Harry’s opinion. Sure, the scene would still feel forced as hell, but it wouldn’t be as disappointing.

Now, I don’t want you to think I’m asking you to write a gay character into the Dresden Files. In fact, I’d rather you didn’t, because god, tokenism. The fact that gay men aren’t heroes in urban fantasy is the entire reason that I write urban fantasy myself, because I want a hero too, you know? So I don’t want another apology scene, or a plucky gay wizard or werewolf or whatever popping on the scene in the next Dresden Files. You inadvertently stepped into a little bit of a quagmire and the more you try to pull out of it, the worse it’ll get until, well, you want to strangle yourself. And well, don’t strangle yourself. We’re still cool.

Now that that’s out of the way, let’s go write some stories, huh?

Sincerely,

Vaughn R. Demont

October 26, 2013

Justifying My English Degree: Life is Hard, the Upswell of Empathy Games

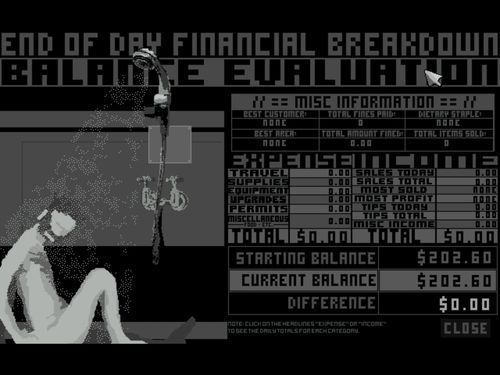

No clue why an adjunct would play a game like this. Nope. No idea.

Life is hard, few people would argue that point, though what makes it hard is always a topic for discussion. Stress, work, the whole “hell is other people” thing, it all feeds into the need to occasionally just take a break and escape from it all. I’ve told some of my students that the way that I deal with them after a long day of teaching college freshmen is to go home, turn on my Xbox, and play Payday 2.

That’s the reason we play these kinds of games, why we hop onto various and sundry online games and blow each other away and perform acts that would likely get us imprisoned, or at the very least deported. But that’s obviously not what games are for. It’s been suggested that games are becoming the new literature, a form of storytelling that demands interactivity, yet at the same time follows the same paths to the same expected point. While the Limbos and Braids and Bastions and Journeys of the gaming world have been tugging at our heartstrings and also making us believe that we were lucky to not be eviscerated by spiders during our childhood, another new genre has been creeping out of the indie market in the last few years: the so-called “empathy game”.

Empathy is present in a lot of modern games, though it’s often used to hold up a mirror and make the player face their own reflection, whether it’s reenacting Heart of Darkness with a third-person shooter or famously forcing pirates to live through the fate they’re inflicting on indie game developers. The most successful story-based games are often the one where you feel a personal connection to the character, though it could be argued that that’s sympathy, not empathy.

Can’t imagine why major game studios wouldn’t do games like that. Nope. No idea.

The point of the empathy game is to make the player feel exactly what the genre’s about: empathy for someone they normally wouldn’t consider. The more known examples of the empathy game usually revolve around a member of the working poor, highlighting the hard choices that must be made to ensure one’s survival. One of the common traits of the empathy game is then in its difficulty: tutorials are rare, the speed is high, and the punishment for mistakes often has dire consequences, often taken on on the player-character’s family or other loved ones. The protagonist is often unnamed to encourage self-insertion, to give the player the sense this is all happening to them, or, better said, could happen to them. That being said, empathy are supposed to be difficult to “win”, i.e. get the happy ending, because like the title of the blog entry says: life is hard, and empathy games strive to remind us of that.

Because all of us working poor end every day with crying in the shower.

Granted, they don’t always succeed. Cart Life bucks a few trends of the empathy genre off the bat. Though the creator has himself labeled it as a “retail simulator”, critics have lumped it in with the empathy genre simply because of the subject matter: you choose a down-on-their-luck person with limited funds and limited time to make the rent to start a food or coffee cart to make ends meet. The difficulty is ramped from the get-go, with an unhelpful file and no advice on how or where to find a cart, where to get supplies, where to set up, how to serve customers, which leads the player to going by trial-and-error, which is likely where the empathy angle comes in, since this is often how things go in life. It’s possible to be beaten, mugged, arrested, and heavily fined in this game simply for setting up shop in the wrong areas that you had no idea you weren’t supposed to be in. Essentially, it smacks of The Witcher, punishing you for failing at things you had no idea how to do that it refuses to teach you, except that it offers a restart option (which you don’t get in real life). While it tugs the heartstrings through financial hardship (especially with the single mother character), some of the hardships feel too exaggerated to elicit much empathy. One fine for selling without a permit can ruin your chances of making rent, one mistake making change leaves you without money for the rest of the day, permits are exorbitantly expensive and usually require bribes to obtain, and there’s always the possibility that before the day is out you’ll be beaten half to death by a kebab vendor or mugged on the way back to your crash space. Cart Life wears its anti-authoritarian colors proudly, but at the end of the day, maybe it’s just what the creator calls it, a “retail simulator”. For a real taste of bureaucracy though, one look no further than Papers, Please.

Can’t imagine why people would think this is a critique of our own customs dept. Nope. No, sir.

Described as a “dystopian document thriller”, Papers, Please contains all of the menial labor of Cart Life, but instead puts it in its proper frustrating context. Set in a country that’s an obvious stand-in for Eastern Europe just before the fall of the Soviet Union, the game puts the player in a tiny windowed office to deal with a never-ending line of people at a border checkpoint. Plenty has already been written about the game itself, but what about the “empathy” angle? Considering that’s it’s based in a Cold War era country that likely wouldn’t exist today if it ever did exist, and that it involves stamping visas yes or no, what’s the point? The premise is simple: you’re picked and thrown into a job that you have no idea how to do other than simple instructions that grow more complicated with each passing day to support your starving family. One could easily ask if these are the sorts of things our own customs and immigration officials have to deal with on a daily basis, and the dozens people and hundreds of documents they have to look over and verify. It’s also in Papers, Please that the player must make the sorts of hard choices that have no real right answer, offering the “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” mindset that’s often required to survive, rather than thrive in the settings an empathy game. Do you become a rubber-stamp guy, since you get paid by the approval and your kid is sick, or do you hope he’ll get better so you don’t risk getting fired? It’s games like Papers, Please that confront players with these sorts of moral quandaries that they won’t find in a AAA title, often because it’s those kind of decisions we play games to escape making just for a little while. But still, when it comes to an empathy game that forces hard choices, even Papers, Please must stand in awe of Spent.

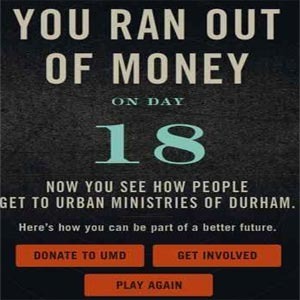

Originally conceived by a partnership between an ad agency and the Urban Ministries of Durham, Spent brings back the chilling belief of the 1980s that “any family is one missed paycheck away from homelessness”. Probably one of the original and most jarring of empathy games, Spent creates no unknown country, no job you’d likely not take, it simply puts you in the shoes of a single parent in the working poor and challenges you to make it to the end of the month. You start by finding a place to live and balancing commute time vs. rent price (and likely end up living up to 50 miles away), then finding one of the few jobs open to, well, anyone, and making a go of it. The terrifying thing is that the stumbling blocks to survival are so… ordinary. Bad colds, public transportation being late or just missing the bus by a couple minutes, having to buy school clothes for your kid and the cheapest quasi-nutritional food possible… All of it serves as reminders to anyone who’s been on that side of the line, and that all it takes is one bad month to put you out on the street. With Spent, there are no mini-games for your job, it’s simply expected you’ll know what you’re doing (though temps have to pass a typing exam). Instead, everything rides on the cost decisions you have to make, the game often following with sobering statistics to remind you that yes, cost is one of the big reasons the working poor don’t have health insurance. Empathy is one of the traits that the internet both cultivates and obliterates, depending on whether you’re the sort of person who reads the comments section. One of the reasons that Spent elicited so much attention is that it didn’t hide behind a fantasy, and that most of the people who played it were people who were already living the situation they were playing, and a lot of the detractors failed to get the point.

Originally conceived by a partnership between an ad agency and the Urban Ministries of Durham, Spent brings back the chilling belief of the 1980s that “any family is one missed paycheck away from homelessness”. Probably one of the original and most jarring of empathy games, Spent creates no unknown country, no job you’d likely not take, it simply puts you in the shoes of a single parent in the working poor and challenges you to make it to the end of the month. You start by finding a place to live and balancing commute time vs. rent price (and likely end up living up to 50 miles away), then finding one of the few jobs open to, well, anyone, and making a go of it. The terrifying thing is that the stumbling blocks to survival are so… ordinary. Bad colds, public transportation being late or just missing the bus by a couple minutes, having to buy school clothes for your kid and the cheapest quasi-nutritional food possible… All of it serves as reminders to anyone who’s been on that side of the line, and that all it takes is one bad month to put you out on the street. With Spent, there are no mini-games for your job, it’s simply expected you’ll know what you’re doing (though temps have to pass a typing exam). Instead, everything rides on the cost decisions you have to make, the game often following with sobering statistics to remind you that yes, cost is one of the big reasons the working poor don’t have health insurance. Empathy is one of the traits that the internet both cultivates and obliterates, depending on whether you’re the sort of person who reads the comments section. One of the reasons that Spent elicited so much attention is that it didn’t hide behind a fantasy, and that most of the people who played it were people who were already living the situation they were playing, and a lot of the detractors failed to get the point.

Empathy games are tricky because they elicit one of three emotions, generally: empathy, apathy, or arrogance. For every person taking the time to stop and think about the message of Papers, Please, there’s a person saying “meh” or a person rolling their eyes and declaring they’d never be stupid enough to be in that situation. For every person who cringes at every decision of Spent, there’s a guy posting screenshots of his final “score” and betting his friends can’t beat it, and another guy firing off a trollish anti-poor rant in a comments section somewhere. This is likely why empathy games will be forever confined to the indie stable, because there’s not a lot of money in a game you can’t “win”, and let’s face it, a lot of us would like to believe that there’s a way to “win” at life, and being shown reminders that that’s unlikely is hardly a tempting proposition.

August 23, 2013

Vaughn’s Interview On The Goddard Hour

Remember that interview I gave at the beginning of August? I recently received the audio file, and mostly thanks to my guy, it’s now available for you guys to listen to with just a click. Personally, I still can’t believe I sound like that…