K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 12

September 11, 2023

Where Should You Start Plotting Your Story?

Where should you start plotting your story? Why, at the beginning of course! Except… when it comes to fiction, it’s not always that simple, is it?

Where should you start plotting your story? Why, at the beginning of course! Except… when it comes to fiction, it’s not always that simple, is it?

One of the key principles of story theory is “the ending is in the beginning.” What this means is that any consideration of how best to begin a story must always include considerations of how best to end it—not to mention all the stuff in between that gets you to the ending. So “where should you start plotting your story?” is a legitimately thoughtful question for any writer to ask—as did Max from Australia:

I went back to a redraft of an earlier redraft of a novel and started at the end. I am working backwards to the middle section—which I was never quite happy with—and see how I can do a better structural job. So maybe one day you could post about where to start the story: back-end, middle or front-end.

Outlining Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

First off, let me just distinguish that what we’re discussing here today is not so much the question of whether you should write your story chronologically, but whether you should plot your story chronologically. Of course, for writers who prefer to discover plot as they write, this distinction won’t matter. But for the rest of us, it can often be helpful to realize that while we may be at our best writing the scenes of the first draft in chronological order, we can—and probably should—consider our plot from a perspective that lets us jump outside the story’s chronological time and space so we can gain a big-picture view.

The Bird’s Eye View: Structure in Outline

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Some writers prefer to outline the story’s plot before writing the first draft; others prefer to analyze the plot after winging the whole thing in a rough draft. Either way, every writer must eventually step back and examine the plot from a bird’s-eye view.

When we do this, what are we looking for? One of the first things to examine is the structure of the plot. And how do you do this? Start by identifying the structural throughline. This will include all of the major structural moments in the story. As I teach them, they look this:

1. Hook – 1%

2. Inciting Event – 12%

3. First Plot Point – 25%

4. First Pinch Point – 37%

5. Midpoint/Second Plot Point – 50%

6. Second Pinch Point – 62%

7. Third Plot Point – 75%

8. Climax – 88%

(^In this interview with Studio Binder, I break down the eight beats of structure and talk about how they show up in Jurassic Park.)

No matter how complex your story, these eight beats should always come together to create a unified whole. Aside from their own unique structural roles, they should all be about the same thing. They should all feature your protagonist as the primary actor. And they should all function together to tell a unified story.

Indeed, if you’re uncertain how to summarize your huge sprawling novel for a query synopsis, just focus on the structural beats. What happens in these beats is what’s most important to your story. You should be able to tell someone the entire story just by describing these eight beats. If any one of these beats sticks out as “the one that doesn’t belong,” that’s a sign that the structure has gone astray in at least that one place. (Need some examples of how to do this? Check out the Story Structure Database.)

This is how you troubleshoot a plot after you’ve already created it. But what if you haven’t yet created it? In that case, as Max asks, is there a specific structural beat that offers the single best starting place for creating cohesion and resonance in all the other beats?

The short answer is: no. You can begin crafting your plot anywhere within the story’s chronology. The when and the where isn’t important, as long as you make sure all the other beats come together to create a unified whole.

Largely, the best approach will come down to two factors:

1. The Author’s Own PreferenceHow does your brain like to work? Those who are linear-brained generally do best when we can work as chronologically as possible. Those who prefer the mind-mapping approach may do better to jump around more. Sooner or later, however, we all have to hone both skills. Linearity is clearly important in the art of writing fiction, but so too is the flexibility required to repeatedly zoom in and out to make sure everything is working on both the micro and macro levels.

2. What Idea First Comes to YouPersonally, I’ve never plotted any two novels in quite the same way. Every story is, as I like to say, its own adventure. How I approach figuring out a story’s structure always depends on what ideas come to me first. Sometimes the ending will be the clearest; sometimes the beginning. Other times, it will be the First Plot Point or Third Plot Point that comes as the formative idea—and everything else is shaped around that.

Where Should You Start Plotting Your Story? It DependsThe longer answer to the question of “where should you start plotting your story?” is: it depends. Following is a quick overview of the main concerns when plotting a story depending on where it makes the most sense for you to start brainstorming according to what scene ideas are already in the bank.

Beginning at the Beginning (Premise)The most obvious place to begin is always at the beginning. If you need to begin planning your plot structure based on an idea for an opening scene, then the good news is that you get to work (or at least start out working) in chronological order, an approach that lends itself to an organic unfolding of cause and effect in your own imagination.

The “bad” news is that you still have everything to figure out about the rest of the structure. Usually, the best place to start this process is by using what you know about your opening scene to build your story’s premise. Even if all you have at this point is an opening scenario, you can start intuiting the structure that will follow by imagining what sort of premise will arise from this scenario.

At its simplest, the premise is a short summation of what the story is about. I prefer working with a one- or two-sentence premise that distills specific aspects of the story, allowing me to quickly identify the major mechanics I will be utilizing going forward. Although you can always modify your premise sentence as you go, having this as a starting place offers a useful touchstone for creating cohesion as you dream up the structural beats that will follow. (You can find guidelines for this in my Outlining Your Novel Workbook and the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software.)

For Example: The premise sentence I’m working with at the moment for my fantasy Wildblood is “An immortal knight cursed to protect the realm forever must journey with a dying queen to an ancient well, in hopes that her magical bloodline may be able to end the apocalypse of eternal winter before a fabled sorcerer can steal all their powers.”

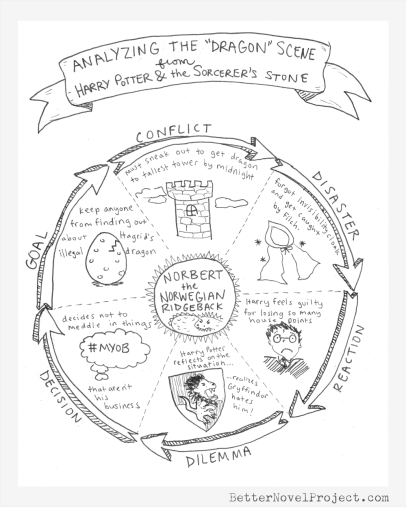

Beginning With the First Plot Point (Conflict)Personally, one of my favorite places to begin plotting is with the First Plot Point. This is the first major structural moment in the story, providing the turning point between the Normal World of the First Act and the Adventure World of the Second Act. It’s a big moment in any story. If you know what you want to have happen here, then you will already know quite a bit about the story.

The First Plot Point is the moment in the story when your protagonist fully engages with the story’s main conflict. The setup of the First Act is now over and the story’s conflict will now be full-on (whether that means drama, romance, or action). By examining how the conflict functions in your story’s First Plot Point, you can figure out how it will progress from here.

Behold the Dawn (Amazon affiliate link)

For Example: I started with the First Plot Point when plotting my historical love story Behold the Dawn, which is about a marriage of convenience between a mercenary knight and an on-the-run widow. Even before I knew anything else about this story, I knew this beat would have to happen, since it features the wedding that kicks off both aspects of the main conflict—their marriage and their escape from those who are trying to kill them both.

Beginning With the Midpoint (Moment of Truth)In many ways, the Midpoint is the most crucial moment of the story. Everything (literally) hangs upon this central moment, not least because it thematically features a Moment of Truth, in which the characters will be faced with a difficult realization about themselves and their best path forward toward their goals.

No matter how you look at the Midpoint, it is a loaded moment for the plot, character, and theme in your story. This makes it a prime place to begin plotting your story. The main gift the Midpoint gives you is the Moment of Truth. If you know what huge realization your characters will have—one that will both change their direction in the plot and their own internal perspectives within the character arc—you will know a lot about your story. Its central location means you can then extrapolate a lot about both what’s come before and what will come after.

One of my favorite models for thinking about the Midpoint is James Scott Bell’s concept of the “Mirror Moment”—in which the protagonist is brought face to face with himself, perhaps literally via a mirror or perhaps only symbolically in a way that forces him to an internal reckoning between the Lie he has so far believed and the Truth that is now knocking at the door.

Storming (Amazon affiliate link)

For Example: One of the earliest scenes that came to me for my historical dieselpunk adventure Storming was the Midpoint. In this story, [kinda a spoiler, but not really because the back cover will tell you as much] a barnstorming biplane pilot clashes with air pirates in a dirigible. The Midpoint is the first moment when the pirates stop skulking in the clouds and make themselves known during a spectacular battle at an airshow. Knowing the story was building toward this allowed me to plan all the scenes leading up to the battle—and all those leading away.

Beginning With the Ending (Climax)Next to beginning with the beginning, probably one of the most popular choices is beginning with the ending. This is a sound choice. As mentioned at the top of the post, if you know how to end the story, then you have all the material you need to know how to properly begin it.

Your idea for your story’s ending might focus on the final moments of the Resolution, after the main conflict has been resolved. Or it might focus on the high action of the Climax, which does the resolving. Either way, knowing how things will turn out for your protagonist will give you sound ideas for how to set up everything that comes before. Knowing how your story ends gives you insight into what kind of character arc your protagonist is following, what thematic premise your story is “proving,” and how the conflict will be resolved (i.e., in the protagonist’s favor or not). Using this info, you can then circle back to the beginning to make sure you are properly setting up and foreshadowing everything that will come.

Wayfarer (Amazon affiliate link)

For Example: Although I don’t always know the events of my story’s Climax right away, I do usually know how I want the story to end. With my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer, about a young man in Georgian England who gains superpowers and fights crime in the Dickensian underbelly of London, I knew I wanted (spoiler) a poignant ending that showed him, now an outlaw, nobly leaving his would-be love interest in order to continue “wayfaring.” (/end spoiler) From this, I began to figure out what type of character arc he would be following (one in which he started out with not so noble motives) and what sort of conflict would create the circumstances of this final scene.

***

The reason it really doesn’t matter where you start plotting is simply that eventually you’ll have to bounce around and cover everything else anyway—and then bounce back to the place where you started to make sure it still fits with all the other plot pieces you’ve created. This is the great challenge of writing longform fiction—making sure all the many, many pieces hang together in a neat row that resonates with readers on all levels. Plotting is rarely a simple proposition, no matter how you do it. The secret is two-fold:

1. Understand structure, so you know what each piece is designed to do and how it affects all the other pieces.

2. Rely on your own instincts to guide you to the scenes and ideas that feel rich enough to propel your exploration of everything else in the story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Where do you start plotting your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Where Should You Start Plotting Your Story? appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

September 4, 2023

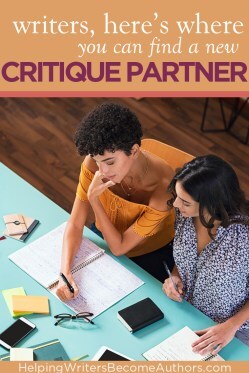

Find a Writing Buddy! (New Edition)

Need a writing buddy? A critique partner? A beta reader? Here’s your stop!

Need a writing buddy? A critique partner? A beta reader? Here’s your stop!

Earlier this year, I posted a “writing buddy linkup,” which opened the comments to anyone looking for a critique partner or accountability partner for their writing. The post was wildly popular and continued to receive entries throughout the year. At last count, it had over 500 submissions.

That many comments can be difficult to wade through, and I’m sure quite a few submissions got lost in the process. So I’m opening it up again! Feel free to post again if you weren’t able to find the right connection last time.

Need a Writing Buddy? Here’s HowJust leave a comment! Tell us:

Your genreA short summary of your current storyYour level of experience (i.e., how many years you have been writing)What you’re looking for in a writing buddyYour email address (I recommend formatting it as follows to avoid risk of spam: kmweiland [at] kmweiland [dot] com)You can subscribe to the comments so you can read additional entries as they come in (however, be aware there could be a lot of comments!). If you see someone you think would be a great match for you, drop them a line!

The writing life works best when we’re able to reach out and offer a helping hand to one another. Jump in, meet someone new, and start taking your writing to the next level!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! What are you looking for in a writing buddy? Tell us in the comments!The post Find a Writing Buddy! (New Edition) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 28, 2023

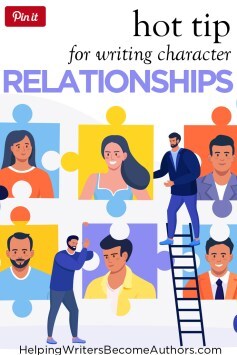

Hot Tip for Character Relationships: The Relationship IS a Character

Character relationships are at the heart of most stories. Few protagonists successfully exist in a vacuum. Most will be contextualized by their supporting cast. More than that, the relationships between characters are often the single most interesting and entertaining element in any story.

Character relationships are at the heart of most stories. Few protagonists successfully exist in a vacuum. Most will be contextualized by their supporting cast. More than that, the relationships between characters are often the single most interesting and entertaining element in any story.

When asking me about my own fiction, people sometimes wonder where I find my first germ of an actionable idea: plot or character? My answer is that I never know if I have a story worth telling until I have two characters talking to each other. (And, of course, that is plot at its simplest.)

Certainly, as a reader or viewer, I am usually less engaged by any one character than I am by character relationships. This dynamic is most obvious in relationship-oriented stories such as romances, but it is key in genres of all sorts. For example, the reason I love the film Warrior isn’t so much because I particularly like any one character, but rather because I am engaged by the relationship between the the two estranged brothers who will end up fighting each other. (Although let’s be honest, hot Tom Hardy doesn’t hurt.)

Warrior (2011), Lionsgate.

This seems obvious enough, but it’s surprising how often writers take for granted the importance of character relationships. I have read and watched waaaaayyy too many stories that sidelined their most important character relationships—and ended up boring and frustrating me as a result. This happens most often in series, in which authors attempt to add layers and deepen complexity by splitting up characters to create new subplots. However, this doesn’t always work for the simple reason that this approach can end up removing or shortchanging the story’s best element.

Think of Character Relationship as “The Third Entity”One of the simplest tricks for leveraging character relationships in your story is to stop thinking about a fictional relationship as a sum of its parts (i.e., two different characters who come together wherever it is convenient for the author) and instead to start thinking of the relationship as an entity of its own.

Actually, there is a deeper truth here. Every relationship is, in fact, its own entity. Let’s say you and I are friends. Within this equation, there is the entity that is you as an individual, the entity that is me as an individual, and the third entity that is our relationship. The relationship is its own thing, has its own energy, its own container, its own goals and purposes. Healthy relationships are those that are less about one person nurturing the other and more about both people nurturing the container that is the relationship itself.

Attached by Amir Levine and Rachel S.F. Heller (affiliate link)

In Attached, doctors Amir Levine and Rachel S.F. Heller call this a “biological truth”:

Numerous studies show that once we become attached to someone, the two of us form one physiological unit. Our partner regulates our blood pressure, our heart rate, our breathing, and the levels of hormones in our blood. We are no longer separate entities.

This is a helpful perspective through which to view relationships in our own lives, but it is also a useful way to think of character relationships. In any two-party relationship, you will be dealing with three entities: the two characters and the relationship itself.

When you view character relationships in this way, you can start plotting with not just the characters in mind but also their relationship. This is also a simple means for ensuring your story does not become too plot-centric. Even if the dynamic between your characters is entirely focused on working toward a mutual goal, you get to use this goal to facilitate the third entity, which is the relationship.

What If You Need to Split Up Your Characters?Focusing on character relationships is easy as long as you’re writing a relatively simple story that allows characters to remain in the same setting with the same goal. But what if you’re writing a sprawling, plot-heavy story, in which logistics require characters to split up and go their own way? Will this irrevocably damage your story and frustrate readers?

It depends. Here are a few options, depending on the needs of your story.

Avoid Splitting Up Character Relationships

Secrets of Story by Matt Bird (affiliate link)

It’s always a bit dicey to split up characters who have a good dynamic. If you’ve been fortunate enough to write a character relationship that your audience loves experiencing, then destroying or suspending that dynamic may not be your smartest choice. Before proceeding, dig deep enough to examine whether this is truly the best option for your story. Your audiences is here, first and foremost, not because they want the plot to work—but because they want to be entertained. Or as Matt Bird says in Secrets of Story:

Audiences purchase your work because of your concept, but they embrace it because of your characters.

Obviously, the plot is important too, but if you bore or annoy your audience, they may not stick around to experience the plot.

Take a step back and truly consider whether pulling an established and successful character relationship is your best bet. Several fantasy stories pop to mind that lost me because they isolated the protagonist from the relationship dynamics that were initially most interesting to me. Beware of overcomplicating your plot at the expense of the most foundational elements. Sometimes the simplest aspects of a story are the ones that offer the most potential for success.

Choose the Most Interesting Group PairingsIf you’ve double-checked yourself and decided that, yes, splitting up your characters is your best choice, make sure you’re replacing the lost relationship dynamic with a new one. Just as audiences can (and should) enjoy more than one character, they can also enjoy more than one relationship dynamic. Accomplishing this requires care. Particularly if the initial relationship dynamic was excellent, you’ll have to dig deep to make sure the new ones measure up.

If you’re splitting your cast into multiple groups (presumably so they can cover more ground in the plot), then make sure you are creating pairings that offer the most bang for your buck. Look for characters who have chemistry and/or natural antagonism. The best character relationships are usually those that prompt significant growth for one or both characters. This can be accomplished in multiple ways, but the simplest is to make sure these characters have rough edges that rub against each other.

The show Stranger Things generally does an outstanding job of this. Throughout its first four seasons, it successfully juggles its huge cast into multiple different pairings, allowing audiences to experience the characters in different dynamics that reveal different aspects of their personalities.

Stranger Things (2016-), Netflix.

Most importantly, all of the relationships offer stakes that are equally meaningful. For example, Dustin cares as much about his relationship with Steve as he does his relationship with Mike as he does his relationship with Suzie—and all three relationships are also important and interesting to audiences, allowing Dustin to successfully move about the storyworld without viewers ever feeling the show is missing out on something vital.

Provide New Relationship EntitiesIf you need to send a character into an entirely new situation, you may find you need to introduce new character relationships altogether. You must promptly establish that the new characters can offer just as much entertainment value as those from previous relationships (something Stranger Things failed at in the notorious Episode 7 from Season 2, which focuses on Eleven’s interval with the punk robbers led by her superpowered “sister” Kali).

Stranger Things (2016-), Netflix.

The key is to ensure new characters are not simply placeholders within the plot until your primary character can return to previous relationships. Although this means digging deep to make sure these new supporting characters are as dimensional as anyone else in the story, it doesn’t necessarily mean the character requires a huge backstory and lots of detail. What’s important is that the relationship dynamic is charged enough to be entertaining. Your audience needs to be so engaged with this new relationship that they will want to experience it for its own sake, rather than wanting to skip ahead to get back to a more interesting dynamic.

For example, when the fellowship breaks in The Lord of the Rings, characters go off in different directions, all of them forming new relationships—all of which are dimensional and thematically entertaining in their own right. Most of members of the huge cast in this story are not introduced until the second installment, but almost all of them are so fully realized in their relationships with the original cast members that they are just as iconic as those from the first book.

The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002), New Line Cinema.

Make the Time Apart About the RelationshipIf a certain relationship is of primary importance to the story and yet you still feel the need to split up the characters for a time, consider how you can make their time apart about the relationship, thereby keeping alive the original dynamic. This is by far the trickiest aspect to pull off, but sometimes it must be done due to the logic of the plot or simply to create the necessary stakes or consequences of time spent apart.

>>Click here to read “How to Structure Stories With Multiple Main Characters?”

Warrior did this well; the brothers are hardly ever together within the story’s timeline, yet their relationship is always front and center.

Warrior (2011), Lionsgate.

Sing My Name by Ellen O’Connell (affiliate link)

Another successful example is from the western romance Sing My Name by Ellen O’Connell, which splits up the romantic couple for a lengthy section, but keeps readers attention via skillful characterization as well as all of the abovementioned techniques.

What Creates Successful Character Relationships?Character relationships offer a vehicle for expanding and improving almost every aspect of fiction.

Character relationships are at the heart of character arc and development, providing catalysts and conflict to reveal personality and to prompt growth and change.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Character relationships create a medium in which to develop the plot. Protagonist and antagonist are the most obvious duo to drive plot, but any important relationship in fiction offers the opportunity for stakes and consequences. Relationships highlight what is important in a character’s life (whether the relationship is what’s most important or not), offering motivation for all actions.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Character relationships are also the proving ground of theme. The differences and similarities amongst characters is what offers the thematic contrast and context that illustrates any thematic argument. Therefore, good character relationships are simply good fiction. If your character arcs, plot, and theme are working well, it’s likely because the foundation of good character relationships is already in place.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

More than that though, character relationships give birth to one of the single most entertaining aspects of fiction: dialogue. Whether or not a character relationship works and engages readers depends in large part on how well the dialogue works. If the characters’ chemistry allows them to demonstrate and develop the relationship through skillful dialogue, it’s almost a sure bet audiences will like the dynamic and want to follow it through the story.

This is obviously true in a relationship-centric story, but it’s just as true in stories in which the primary relationship character functions as little more than a dialogue buddy. For example, most of us enjoy the Sherlock Holmes stories as much for the dynamic between Holmes and Watson as for the plot elements of the mysteries.

Sherlock Holmes (2009), Warner Bros.

Perhaps the single most useful litmus test for successful character relationships is simply whether or not they matter.

How does the relationship affect the outcome of the plot?How does the plot affect the outcome of the relationship?How is this relationship a proving ground for everything that happens in this story (whether your story features a romantic couple or a parent-child dynamic or friends or colleagues or enemies or strangers who pass in the night)?Ask yourself whether engaging character relationships show up on every page of your story. If yes, that’s your first green light. Then ask whether the prominent character relationships matter to the story. If yes, that’s your second green light—and you’re good to go.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think creates dynamic and engaging character relationships? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Hot Tip for Character Relationships: The Relationship IS a Character appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 21, 2023

How to Rediscover the Joy of Writing

It’s something of an irony that most of us come to writing because we love it—and, yet, it’s actually really freaking hard. Only somewhat tongue in cheek, I will often advise that if “you can not be a writer, then don’t.” And yet it is abundantly clear that more humans than not need to write. (And my more truthful advice is “everyone should write.”) But what happens when you lose the joy? Is there a way you can learn how to rediscover the joy of writing you experienced way back at the beginning of your journey?

It’s something of an irony that most of us come to writing because we love it—and, yet, it’s actually really freaking hard. Only somewhat tongue in cheek, I will often advise that if “you can not be a writer, then don’t.” And yet it is abundantly clear that more humans than not need to write. (And my more truthful advice is “everyone should write.”) But what happens when you lose the joy? Is there a way you can learn how to rediscover the joy of writing you experienced way back at the beginning of your journey?

Here’s the thing: we may initially come to writing because it brings us joy, but I think we tend to keep writing as a search for joy. Whether we’re writing purely for entertainment and escape or as an attempt to explore and make sense of the human experience, writing is one of our most powerful tools for healing, growth, and transformation. This means that, by its very nature, writing is a journey of change. If we start the scene with joy, we can know we will eventually arc into disillusionment, frustration, and perhaps even sorrow. But if we keep writing, we can also be assured we will arc back into joy.

Over the last few years, I have been sharing the occasional post from behind the scenes of some bumpy moments in my own writing life. I have arced through all of the above emotions, all the way down into the despair that perhaps writing was done with me and I was done with it. But I stayed with it and am quite happy to report that, yes, I learned how to rediscover the joy of writing.

Recently, I received several emails on this subject, asking that I comment on the need to learn how rediscover the joy of writing and to offer any insights from my own journey down this road. One email was from long-time reader Joseph Merboth, who eloquently expressed a disillusionment with writing that I think many writers experience at one point or another (and who graciously allowed me to share his words):

This is perhaps too specific a question or too personal to my life. But I also know that you believe writing reflects life and vice versa, so maybe the answer lies somewhere in between.

For the past 7 years I’ve relentlessly pursued writing, but now I’m questioning everything. Do I want to be a writer, or do I just want the freedom to create at-will and not work a normal job? Do I love storytelling or am I just geeking out about the mechanics? Am I creating from a sense of joy or of duty?

One problem is that I never had an infatuation period. I was a latecomer to the party (relatively speaking), so there are no early memories of terrible novel attempts to look back on fondly. My love comes from reading, and somewhere along the way I realized I didn’t want to just consume anymore. This led to me studying the craft, which was thrilling at first as I uncovered a complex world of symbolism and rules and rule-breaking. But it has also served to disenchant my reading. I’m no longer in awe when I read a good book; I’m either self-satisfied because I know how it works or I’m lost in analysis.

If I’m being honest, each day of writing is a chore. That’s to be expected at first, but seems like a bad sign 7 years on. I think I’ve also lost sight of my ambitions. I used to write with a desire to change lives, to be an inspiration and bring hope. Ah, the naïvety. I’ve grown cynical in the last few years (something you might relate to), and that calls into question why I’m doing this at all.

Is it possible to rediscover the joy? How do you put your heart into it when you’re writing out of obedience to your schedule, your self-expectations, or your flimsy sense of purpose?

If you can’t identify with any of this, feel free to ignore my email. I just thought there was a chance you’d worked through some of the same questions yourself.

Sorry to be a downer! Your blog posts have had a new vitality lately, so I’m hoping that means you’re moving onward and upward.

Today, I want to share a few of my thoughts on the topic of learning how to rediscover the joy of writing. I can’t speak to a universal experience for all writers, but I can speak to my own experience, in hope it may provide context for others who are struggling through some of the more difficult phases of the journey.

Are You Transforming? (Or, The Stages of the Writing Life)The first thing I would emphasize is that the writing life is a journey. It is a not a straight line to the horizon; it is not a one-size-fits-all container that holds the same experience for every one of us. In fact, if you’re pursuing writing with any degree of honesty and integrity, it is sure to be a highly personalized, often challenging, sometimes volatile quest into the unexplored regions of yourself and human consciousness. This is true not just in regards to what you write, but also in how you relate to the act of writing, your sense of purpose, and your relationship to discipline.

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

No surprise that one of the most intuitive models through which to view the writing life is story structure. Story structure is nothing if not a map to the full panoply of human emotions. Sometimes there’s joy, of course, but there’s a lot of suffering too. There’s a lot of doubt. There’s a Dark Night of the Soul, for crying out loud.

My own experience has shown me that, like most aspects of life, writing goes through phases or cycles (call them “acts” if you want). I read somewhere that three- and seven-year cycles are seen as important in personal transformations and spiritual awakening. I personally resonate with this. The current phase in which I find myself began seven years ago, and I now reach what certainly seems to be a resolution of sorts.

Early on in that cycle, I wrote the post “When Does Writing Get Easier? The 4 Steps to Mastery,” in which I talked specifically about the Arab proverb that says:

At the time I wrote that post, I felt I had experienced all four stages. I wrote that I had reached:

…a very interesting new mountain peak. Frankly, it’s a mountain peak I didn’t know existed. No one ever told me it existed (or, if they did, I laughed at the whole idea and promptly forgot about it). But I’m here to encourage you that it does exist, and it’s name is: The Place Where Writing Gets Easier Because You Actually Get It.

I wrote that with some trepidation, since the acknowledgement seemed to baiting life to come slap me upside the head with the “next” thing. And, boy howdy, it did. Within a year, thanks to a potent cocktail of life experiences, I was struggling to write at all. A year later, I had to admit I was suffering heavy-duty writer’s block.

Not a lot of joy in that period, I gotta tell you. But here’s the thing about cycles: they don’t just repeat, they spiral. If you stay faithful to what the experience is able to teach you in the moment, you will not only advance out of the difficulties of the moment, you will also level up. When you regain the joy of writing, you will find not simply the same old joy that brought you to writing in the first place, but a deeper and more meaningful joy. A hard-won joy.

Why Are You Writing? (Or, The Golden Thread)When we are struggling in one of the ebb periods of the writing life, a relatably common thought is, “What’s the point?” If you’re not enjoying it, if you’re not receiving all the results you’re looking for, then why keep doing this?

This is not a rhetorical question. Maybe the truth of your journey is to push through, to keep going, and to spiral up to that new level of the joy of writing. But maybe it’s not. Maybe writing has taught you what it’s meant to teach you at this point, and it is time for you to listen to a deeper wisdom and journey on to the next phase of your personal journey.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

Indeed, as the crisis points in story structure and character arc show us, these low moments in life are designed to trigger exactly this kind of soul-searching. At the end of the day, the question of “rediscovering joy” isn’t really about writing at all; it’s about life. And, straight up, writing is not the be-all-end-all of that path for every single person who decides to walk upon it for a time.

There is no shame in that. Showing rigorous integrity in being honest about your own reasons and motives for anything is one of the highest callings of being a human.

So ask yourself: “What’s your golden thread?”

Why did you come to writing in the first place? What has kept you writing all this time? And… is it still true?

Many of us come to writing in a haze of idealism. We’re going to make the world a better place. Or maybe just create an awesome lifestyle for ourselves.

Idealism is important. I believe in idealism. I identify as an idealist. But ideals, by themselves, can’t light the dark when the going gets tough. Per shadow theory, when idealism is overemphasized, cynicism is likely lurking in the shadow. That doesn’t mean the idealism wasn’t true, but if it’s to offer accurate guidance, it must first be integrated with all the other truths of one’s self.

One of the reasons writers—especially highly disciplined writers—may be disillusioned is that we can mistake the form of things for the truth of things. This can happen when we do all the “right” things, all the things we would do were we indeed motivated by true passion, wonder, and joy, only to eventually burn out and discover that we have been, instead, simply running on the motivation of “doing it right.” Although putting in that level of work and discipline will always pay off in some areas, if those actions are cut off from our true heart, things will eventually feel flat at a certain point.

However, just because we are more accustomed to referencing “the way to do it” versus “what my heart says,” this does not mean that, when we get in touch with our heart, it won’t indeed want the writing life after all. But (and here’s something I took the long road to learning), it doesn’t count until you actually get into the habit of asking your heart and listening to it.

This is a whole journey of its own, one that for many people who run highly-disciplined personality patterns, often involves the invitation to deep self-work and discovery.

Are You Really a Writer? (Or, Identities vs. Desires)The process of identifying your golden thread can often lead you to the realization that many of your reasons and motives for writing may have more to do with “identities” than “desires.” This is most obviously true in that many of us are deeply identified with being “a writer.” If we were to stop writing, that identity would no longer fit—and that, in itself, can bring up ego resistance from primal places that actually have little or nothing to do with our deepest desires and truths.

Beyond the identity of “writer,” however, we must also examine broader and less obvious identities such as simply “hard worker” or “intelligent analyzer.” Although identities like these often point to personality traits that are incredibly useful and valuable, preserving these identities is not, in itself, a worthy motive. When you wake up one day and realize the only reason you’re writing is because “you’re supposed to,” you suddenly comprehend why writing doesn’t seem joyful anymore.

Another identity to examine is that of “published writer.” Many people grow frustrated with the writing journey when they are unable to access the level of results they feel is necessary to justify their efforts. Perhaps they want to be published, perhaps they want to sell a certain number of books, perhaps they want to make a certain amount of money. When it doesn’t happen, it feels like a cheat, and cynicism moves in to fill the gap.

You have to ask yourself: “Is this really why I’m writing?”

And maybe it is. Maybe you are very clear that the reason you’re writing is because you want it to be a job and pay for itself. When it fails to do that, your truth may well be that it’s time to move on. (And by the way, even if you’re totally in alignment with moving on, you still have every right to grieve the disappointment and the transition on your way to, hopefully, celebrating the lessons.)

If you can acknowledge that material results are not your true motivation for writing, then returning to those deeper reasons, over and over again, can help you focus even in the darkness. Ultimately, this is a process of reclaiming wonder. It is returning to “beginner’s mind.” When we have reached the proverb’s fourth stage—in which “we know that we know”—it is indicative that the cycle is beginning again and we are in fact once more at the first stage—in which “we know not that we know not.”

After we have spent so much time and effort studying and perfecting our understanding of the techniques and theories of our craft, it is common enough to reach a feeling of burnout. It is worthwhile to celebrate our discipline and our accomplishment in how much we have learned. But when we notice our own self-satisfaction or a tendency to over-analyze, that can be turned into a call to return to humility and the recognition that the more we think we know, the less we do.

Therein lies the return to wonder—to innocence. Yes, we still know what we know, but all that allows is for us to stop asking the same old questions—and find new ones. And I’ll be straight: that ain’t easy. Your reward (and I use that word with sincerity) for reaching the mountaintop of knowledge and accomplishment is to realize, Honey, you don’t know nothin.’ If you can identify with that, it becomes much easier to let the path take you where it will.

What Is Joy Anyway? (Or, Embodied Joy)And now, a word on joy itself.

Apart from the mind games we like to play with ourselves and the potentialities for ego evolution, as discussed so far, there is also the little fact that joy absolutely can be lost. And reclaiming it is not as simple as adjusting our mindsets and talking ourselves back into happiness and acceptance.

Joy is a physiological experience. This means that when your body has habituated itself out of joy, getting it back isn’t always a simple proposition.

I do not view joy (or love) as an emotion, but rather as a state of being. This means it is something we can train our bodies to access even when circumstances are not conducive. There are many ways to go about this, and the true journey of somatic reprogramming is far beyond the scope of this post. But I will mention again a little daily practice I do that has initiated long-lasting and life-changing effects for myself. Whether or not you currently find yourself struggling to learn how to rediscover the joy of writing, this is a practice that can deepen your connection with your golden thread—with the truth of how you find and foster meaning in your life.

It’s simply this: While sitting calmly in a relaxed state, close your eyes. Call joy into your body. If this isn’t immediately accessible, try imagining or remembering a time when you felt strong joy. Now, notice where you feel it in your physical body. (For me, it shoots up my spine to the top of my head.) Once you can identify how your body experiences joy, practice accessing this feeling at least once a day. A continued practice will allow you to eventually grow the ability to physically access joy whenever you want. The more you develop this skill, the more powerfully you can wield it.

The One Thing I Would Tell Little Writer K.M.W.I’ve been imagining stories all my life—since my earliest memory. I started writing when I was twelve. I began with nothing but joy and wonder and curiosity, knowing nothing and not even knowing I knew nothing and not caring.

Later on, I started journeying through the well-mapped territories of writing techniques and theories, where I had only to look to the expertise of those who had gone before to guide me.

But eventually, I ran out of map. In order to keep going, I had to walk right off the edge of the known earth and face the dragons for myself.

And out there, in the frontiers, things got confusing. They got scary. There were days when the joy went out of the writing altogether. There were many, many questions—because without the joy, surely it meant I must be doing something wrong.

There were days when I couldn’t always see my golden thread. Then I’d find it again, shining in the shadows. And eventually, in front of me, there was a whole new horizon of light.

And, now? Now, there are days when writing is a slog; days when it is bliss. In other words: back to normal.

All these years later, if I could go back to the side of my very young self—as she was telling herself stories in a treehouse just for fun—would I give her any advice that might make the journey easier? That might ensure she never had to go through all that trouble of losing the joy for a time? Would I tell her not to work so hard, not to burn herself out, and to be so very, very careful never to lose the wonder?

No. I don’t think I’d tell her any of that. I think the only thing I would whisper in her sweet ear is:

“The art isn’t what you’re writing. It’s what you’re living. The story isn’t what’s on paper. It’s your life.”

Without doubt, joy is one of the most important experiences of life. But it’s not the only one. If ever you feel you’ve lost the joy of writing for a time, don’t think of that as an answer to some cosmic question about whether or not you’re destined to be a writer. Rather, I invite you to think of it as a question. What is its absence here to teach you? In my experience, it is only in submitting as a student that we can truly learn how to rediscover the joy of writing.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions? What are your thoughts on how to rediscover the joy of writing? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Rediscover the Joy of Writing appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 14, 2023

What Are Plot Devices? (Why You Should Be Cautious)

What are plot devices? Basically, they’re exactly what they sound like: events that maneuver the plot in particular directions.

What are plot devices? Basically, they’re exactly what they sound like: events that maneuver the plot in particular directions.

All stories are built on plot devices. In truth, everything that happens in a story is a plot device. Story structure beats are plot devices. Character arc beats are plot devices. Plot devices are the little clockwork gears that make a story run.

This means plot devices are also one of a writer’s most important tools. Need to figure out a way to get two characters to show up at the same place at the same time? A plot device is your key. Want two characters to have good reason to hate each other? Plot device!

This isn’t a bad thing. However, the term “plot device” often comes with the negative connotations associated with poorly executed moments that feel contrived or like authors are manipulating events in order to make the plot do what they want.

Now, of course, all writers must “manipulate” the plot to some extent. After all, we’re not just responsible for creating the story, we’re also responsible for steering it. We know we need to get the characters from Point A to Point B, which means coming up with plausible plot devices to move them along the road toward the final Climax.

The trick is to do so in a way that honors the entire context of the story. Each event should arise naturally from the story’s cause and effect. Any time something in a story seems to exist solely to explain a previous event or further a future event, that’s the sign of a contrived plot device. By contrast, a successful plot device is one that seems to exist solely for its own sake—as if it were just as important as any other event—which allows it to seamlessly integrate with the rest of the story.

What Are Plot Devices? 8 PossibilitiesThis topic is on my mind right now, as I’ve been brainstorming my way around the need for a particular plot device in my fantasy work-in-progress Wildblood. Today, I want to talk about how you can recognize obvious plot devices and then how to troubleshoot your own process to determine whether or not the plot devices will seem contrived to readers.

To get us started, here are eight possible ways plot devices may show up in your story.

1. EventAt its simplest, a plot device is something that happens in your story. It could be a birth, a death, a robbery, a wedding, a dance-off, a scam—you name it. Most of the time, we refer to these events as “beats” or “scenes.” We usually only think of them as plot devices when they seem contrived—as if the only reason an event is happening is to either facilitate a different scene or to instigate a particular emotion in readers.

For Example: In Jupiter Ascending, the main characters are betrayed by a friend—an event that exists solely to facilitate certain subsequent plot developments and that is not supported by either proper build-up or motive or by emotional consequences after the fact.

Jupiter Ascending (2015), Warner Bros.

2. InfoAnything that changes the plot moves the plot, something information is capable of doing all by itself. Any time a character learns something new, that’s a plot device. Readers will always trust that new information is important to the story. However, if that information exists only to be interesting in the moment, without being paid off later, then it is likely a poorly executed plot device.

For Example: This one is common in jargon-heavy or worldbuilding-centric stories, which often drop lots of info, not all of which is necessary either for advancing the plot or even just fleshing out the world. In the adaptation of The Witcher, the “cost of magic” (demonstrated by a girl’s hand withering after performing magic) is used as a device to inform the plot early on, but then dropped from the narrative when it becomes inconvenient.

The Witcher (2019-), Netflix.

3. MacGuffinA MacGuffin, as Alfred Hitchcock famously called it, is a thing or person that inspires pursuit throughout the story. The falcon statuette in The Maltese Falcon is one of the most famous examples. A MacGuffin can also be a person or even just a bit of information. This is a powerful plot device, but it only works well when the MacGuffin is not incidental. It needs to be there for more than just a reason to keep the characters moving; it needs to offer meaning to both plot and theme by the end.

For Example: A popular MacGuffin in recent film was the Tesseract in the MCU, which characters pursued through multiple entries in the series. Ultimately, it was a successful plot device, since it remained important to the very end of the original plotline, when it was claimed by the arch-villain Thanos as one of the Infinity Stones.

The Avengers: Infinity War (2018), Marvel Studios.

4. Suspense/CliffhangerPoorly wrought plot devices are often designed to manipulate readers. Now, ultimately, it is a writer’s job to guide the readers’ experience. And to control your readers’ experience, you must control both expectation and emotion. Suspense is a powerful tool for accomplishing both. However, it must be wielded so as to reward trust. If suspense is built or if a cliffhanger is employed, only for the subsequent scenes to dwindle the anxiety and/or outright fool readers, the effect is usually jarring at best and off-putting at worst.

For Example: This a low-key example, but when I think about this trick, I always think of a scene in a Dick Van Dyke Show episode, in which the opening scene has protagonist Rob bursting into the kitchen in a panic to tell his wife “the police are here for us!”—only to have the next scene, after the opening credits, reveal that the police are there for totally mundane reasons.

The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961-66), CBS.

5. ConundrumsMuch of plot revolves around creating conundrums for characters to solve. This is true simply on the level of scene structure, in which a character’s goal will be met with an obstacle, which inspires the need for a solution. It is even more obviously true in genres such as Mystery, which focus entirely on solving puzzles. However, writers must be careful not to create conundrums for the sake of conundrums. If your character has to spend time figuring out something that doesn’t impact or matter to the overall story, then ultimately you’re just wasting readers’ time.

For Example: Much of the plot in Season 4 of Stranger Things revolves around solving the mystery of whether or not a local man savagely murdered his family many decades ago. Because solving this mystery proves crucial to the present-day plotline in which characters are trying to rescue one of their own from a similar fate, the plot device works. Had it not tied together so cohesively, it would have been problematic.

Stranger Things (2016-), Netflix.

6. Plot TwistA plot twist can be one of the most enjoyable types of plot device. It can also be one of the most abused. A plot twist should never exist just for the sake of the twist. It should be a natural and inevitable outgrowth of everything that’s come before and should matter to what comes after. If you could pull the twist without affecting the progression of the plot, you know you’re probably looking at a manipulative plot device.

For Example: For my money, one of the most annoying plot twists was the out-of-left-field reveal in The Avengers: Age of Ultron that Clint Barton/Hawkeye had a secret family. It doesn’t seem so bad in retrospect, since the franchise built on it in subsequent episodes. But at the time, it lacked any setup and felt super-manipulative.

The Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015), Marvel Studios.

7. Bad Guy MotivationEven in stories that beautifully execute the main throughline for the protagonist, clunky plot devices can sneak in as an attempt to justify the antagonist’s motivation. For example, if the bad guy wants the MacGuffin, he must want it for a true reason and not “just because it’s there.” Writers sometimes end up concocting convoluted backstories for bad guys in order to get them to behave in ways that are convenient to the plot. But to truly work, the antagonist’s motivation must be just as inherent to the story as is the protagonist’s.

For Example: The plot of Jane Got a Gun revolves around the revenge antagonist John Bishop is intent on taking against protagonist Jane and her husband Ham. However, even the inclusion of a backstory event indicating that Ham once helped Jane escape from Bishop’s brothel, fails to provide a satisfying motivation for why Bishop would risk so much to hunt down and extract revenge from two people who ultimately did him little harm and with whom he had little to no emotional connection.

Jane Got a Gun (2015), The Weinstein Company.

8. FlashbackA good flashback should function within the story exactly the same as any other scene: it should entertain, move the plot, be properly set up, and create context for what follows. A bad flashback will just feel like a poorly wrought plot device. This can happen when the author tries to use the flashback to introduce information that controls the audience’s emotional experience in a way that isn’t validated by the rest of the story.

For Example: I wrote a small series recently about how the neo-western series The English butchered its backstory by inserting a poorly set-up flashback into the middle the story, primarily (it would seem) for the reason of milking its full shock value.

The English (2022), BBC Two.

7 Questions to Ask to Identify and Improve Plot DevicesNow that you know some of the ways plot devices might show up in your story, here are seven questions you can ask to analyze how effective any given plot device is within your overall story.

1. Am I Emotionally Attached to This Plot Device?Neither a yes or a no answer automatically indicates a problem. But it’s valuable to evaluate how much you want this moment to be in the story. It could be you want it in there because it is legitimately great. But it could also be you’re working overtime to include a “darling” that just isn’t a good fit.

2. On a Scale of 1–10, What’s the Shock Value and/or Fan Service?On the flipside of the previous question, examine your intent for how you want your audience to experience this moment. Are you desiring to create a specific emotion—such as shock? Or maybe you just really want to give them the kind of scene you know they’d love. Either way, recognize that this motivation on your part isn’t enough to prevent the moment from feeling like a poorly wrought plot device. The effect you’re after in any specific scene must be supported by everything else on either side of it.

3. Does This Need to Happen in the Story?Imagine pulling this scene from your story. What would happen? Would the rest of the story fall apart? If you answer yes, this is usually a sign the scene is indeed cohesive within the larger whole. However, you must also examine whether the reason the story falls apart is because you’ve built everything to lead up to this scene—but it doesn’t make sense after that point. If the scene is crucial to set up a specific part of the story (such as the Climax), but otherwise doesn’t fit the tenor or momentum of the plot, that’s the sign of a poor plot device.

4. Do Previous Events Create the Causal Chain That Leads to the Plot Device?This is where you take a look at every scene leading up to this one. Are they all a straight line pointing to this moment? Or does it seem like those previous scenes are more logically building to a different conclusion? Too many stories that run into this problem switch gears halfway through as if telling two totally different stories.

5. Does the Device Create Meaning, Context, or Catalyst for Subsequent Events?Now look at all the scenes that follow the one in question. Do they also form a straight line away from the scene in question, building upon the plot device to naturally create the rest of the story? I always like to think of scenes in a story as a row of dominoes: each one has to bump into the one to follow.

6. Are Characters Properly Motivated to Create This Device?One of the main reasons plot devices feel hokey is that the characters’ reasons for acting in certain ways just don’t make sense. Often, we know we want a particular scene to happen—e.g., a breakup on the day of the wedding—but unless we use the previous scenes to naturally evolve the characters’ motivations, that scene will ring false when it finally happens. Not only will it fail to provide the desired effect, but it will also likely feel manipulative to audiences.

7. Does This Feel Contrived?One of the best rules in storytelling is simply: “You can use coincidences to get your characters into trouble, but never to get them out.”

Again, this all comes down to proper setup and foreshadowing. If an event is shoehorned into a story just because the author wants it there, it is likely to feel coincidental and contrived. But if you doublecheck how you’ve developed and portrayed the characters’ motivations, you can show them doing just about anything and readers will swallow it down.

***

What are plot devices? They’re crucial integers in every story at every step. But unless you’re wary of the pitfalls, they can also be potential landmines. Learning how to identify plot devices and fully support them on every page of your story is a huge step toward writing cohesive and resonant fiction.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions? What are plot devices in your story? How have you handled them? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post What Are Plot Devices? (Why You Should Be Cautious) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 7, 2023

The Two Most Important Tricks for How to Build Suspense

Perhaps the greatest skill necessary to keep readers glued to your pages is learning how to build suspense. Whether you’re writing a thriller or a quiet romance, suspense of one type or another is what makes readers race to the end of your story. Suspense comes in many different flavors, everything from the threat of a serial killer in that thriller to the delayed kiss in the romance.

Perhaps the greatest skill necessary to keep readers glued to your pages is learning how to build suspense. Whether you’re writing a thriller or a quiet romance, suspense of one type or another is what makes readers race to the end of your story. Suspense comes in many different flavors, everything from the threat of a serial killer in that thriller to the delayed kiss in the romance.

Whatever the genre, suspense always results from two important ingredients: a question and a wait.

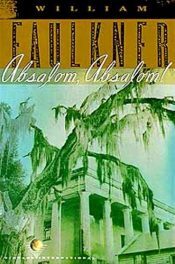

Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner (affiliate link)

We find both these elements in the final chapter of William Faulkner’s acclaimed historical masterpiece Absalom, Absalom!

In this book, the question is, “Who or what has been hidden away in the shack on the old Sutpen plantation?”

The specific question needed to create suspense will vary from story to story, but, ultimately, it always boils down to that age-old demand, “What’s gonna happen?”

As soon as the author has hooked readers’ curiosity with this question, it’s time to make them wait. In Absalom, Absalom!, Faulkner raises the question at the beginning of the final chapter and then does everything possible to delay both the character and the readers from discovering the answer.

Pacing plays a huge role in pulling off a successful waiting period. To force readers to savor every deliciously and frustratingly tantalizing moment, authors need to slow their pacing to a snail’s pace. Faulkner, a master of pacing, does this so beautifully, you can almost see his characters moving in slow motion as they approach the shack, climb the porch steps, enter the house, and start up the stairs. Every moment is drawn out with aching suspense sure to have readers clenching the book with bone-white fingers.

If you can inject this kind of suspense into your story, you can guarantee readers won’t be able to look away.

>>Click here to read 3 Easy (or Easier) Ways to Build Suspense

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How will you build suspense in your story? Tell me in the comments!The post The Two Most Important Tricks for How to Build Suspense appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 31, 2023

How to Write Interesting Happy Scenes? 6 Tips

With so much emphasis in fiction writing put upon the importance of conflict, a seemingly apt question is, “How can you write interesting happy scenes?”

With so much emphasis in fiction writing put upon the importance of conflict, a seemingly apt question is, “How can you write interesting happy scenes?”

This was the question recently posed to me by Elena Singleterry, who wrote:

If possible, I would like to ask a question about writing a happy scene. In my book, the plot calls for a number of such scenes (every time the two lovers reunite, which does not happen often, but does happen throughout the book). My characters are not reuniting in a way where they are enemies becoming lovers or anything like that, but already as lovers, so these scenes are mostly dialogues and happy times together—so no real suspense or conflict there.

There is a conflict that unfolds in between their get-togethers and serves as an external force (such as, heroine’s complicated family situation), but because their get-togethers happen out of direct reach of the external force, their meetings are largely conflict-free. The characters spend these precious days talking, exploring foreign cities (a different city for each of the meetings), getting to know one another more and more. These meetings are meant to show their compatibility and discovery of self, of themselves as two parts of this couple, and the physical/cultural world around them, not as a major source of conflict.

If you feel it would be of interest to your other readers, could you please give a few suggestions on how to make happy scenes engaging?

This is an apt question. Not only are some stories designed to be “happy stories,” but almost any type of story, even the darkest, will feature at least a few happy scenes, for the sake of contrast if nothing else. So if conflict is purported to be the secret to engaging reader attention and keeping them entertained, how can you write interesting happy scenes?

The simple answer, of course, is that readers are not engaged solely by conflict in a scene. Conflict is often too narrowly interpreted as “confrontation,” rather than as something requiring the characters to evolve their goals and their methods for achieving those goals. More than that, as we explored in last week’s post about “8 Different Types of Scenes,” conflict isn’t the only element in fiction that ensures reader entertainment. In fact, variety has a great deal to do with that entertainment.

That said, happy scenes do pose special challenges. This is because they don’t always have access to several of the standard dramatic techniques used to maintain the plot’s forward momentum and introduce the little (or big) surprises that keep a reader’s brain engaged.

6 Tips to Write Interesting Happy ScenesToday, I’m going to offer six tips for anchoring your story’s happy scenes as some of its best scenes.

But, first, a caveat. In addition to a misunderstanding of conflict, one of the primary reasons writers might struggle to write interesting happy scenes is that they are confusing “happy” with “passive.” However, happy moments can and should contribute to moving the plot just as much as difficult moments. For example, consider two characters getting engaged. In most instances, this will be an unequivocally happy moment while also creating definite change in the characters’ lives—and thus moving the plot.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Quieter happy scenes are also important, but should be considered within the overall shape of scene structure and plot structure (both of which I talk about in my book Structuring Your Novel and its accompanying workbook). As we talked about last week, low-key happy moments can often find a comfortable home in the “reaction” or “sequel” half of a scene.

There are occasional instances in a story in which it is appropriate to include scenes in which nothing happens that directly moves the plot. However, those instances are rare and only appropriate when the author is consciously creating a particular effect (see the section in last week’s post about “vignettes,” as well as this post about “incidents” and “happenings”).

The following six tips can be used in any type of scene, but the intent should be to weave these scenes into the story in a way that impacts the plot and/or character growth.

1. Ask, “What’s Entertaining in this Scene?”This step is so simple and yet surprisingly easy to overlook. If you’re doubting whether your happy scene will engage readers, just take a step back and identify what in this scene is designed to be entertaining? What entertains you about this scene? Why are you enjoying writing it? And if you were reading/watching it, what would you enjoy about the experience?

Although the throughline of solid scene structure will contribute greatly to readers feeling pulled into a story’s momentum, by itself this isn’t necessarily what entertains readers. You can put your characters through all the motions of proper scene structure and still write dull narrative. So consider what about this scene is designed to engage, entertain, interest, surprise, or delight your audience. The main weight of entertainment could be borne by any of the following elements:

DialogueMany readers find dialogue to be the most interesting part of a story. (Admission: if I’m reading strictly for pleasure, I will sometimes skim lengthy narrative sections until I find quotation marks.) Dialogue is often conflict-driven, but even just friendly repartee, when it’s quick-witted, is a pleasure to experience.

Love scenesFor romance novels, this is where it’s all at. Note that, usually, these scenes carry huge impact in the story and most definitely drive the plot forward.

CutenessJust the sheer sweetness or adorableness of certain moments can be all the entertainment required. Sometimes watching a character do something unbearably nice can be the best moment in a story. (Or puppies. You could always include puppies.)

The Happiness of Released TensionThe release after a moment of intense conflict can be even more engaging than the conflict itself, as we watch the characters react and adjust—perhaps in ways that weren’t emotionally available a moment ago. The point of conflict is to change something in the story; the moment after is when readers get to experience those changes.

CharismaThere are those special people who don’t have to do anything interesting in order to be interesting. We literally would watch them read the phone book. In written fiction, charisma usually comes down to strong dimensionality within the characters, allowing them to act in ways that are cohesive to their personalities and yet still surprising. Strong narrative tone also plays a huge role.

ChemistryChemistry is charisma happening between characters. It’s the magnetic push-pull between people, in which everything flows and yet nothing can be taken for granted. I’ve written a whole post about character chemistry here.

SettingWhen setting becomes “a character of its own,” then it is possible for a story to entertain readers with scenes in which characters do little more than wander through these evocative places. Needless to say, it is crucial to avoid self-indulgence at all costs in such instances.

ProseWriting, in itself, is entertaining. Good prose can engage readers even when not describing anything inherently interesting. Of course, understanding your genre’s conventions and your readers’ tastes becomes important when relying on prose as the primary entertainment factor in a scene. But as so many amazing literary novels have shown us, the words sometimes matter more than the subject.

HumorHumor can carry a scene all by itself. If readers are laughing, you’ve got ’em. However, humor is certainly not the easiest element on this list to execute and usually works best in concert with other elements to support it.

PoignancyPoignancy is the melancholy cousin of humor. Instead of eliciting a chuckle, it’s more likely to touch our heartstrings, if only subtly. Irony is often the most powerful way to evoke poignancy and to keep it pertinent to the rest of the plot. For example, creating happy scenes that contrast a difficult overall situation can bring the urgency of the main plot challenge into starker focus.

2. Double Down on the Scene’s Emotional ArcOnce you’ve identified what elements within your happy scene will bring the most entertainment value, double-check the scene’s emotional arc. As mentioned above, just because a scene doesn’t strongly feature conflict doesn’t mean nothing is happening. This is true even in scenes that feature little to no external action. Your characters may spend the entire scene comfortably sitting on a park bench throwing bread to ducks, but as long as there is internal change—aka, an emotional arc—then the scene will still have progressed the plot.

Ask yourself:

How is the character’s mood or outlook different at the end of the scene from the beginning?What emotion begins the scene?What different emotion ends the scene?3. Check on the Scene’s Forward Momentum or ThroughlineAlthough “conflict” gets most of the limelight, what is really being asked for is “change.” This is what it means to move the plot. If something is changing in your scene that affects the scenes to follow, you can be sure it’s moving the plot.

When writing a happy scene (or any type of scene), ask yourself: “What happens in this scene that changes something for the characters?” This could be a big change that affects where the characters are in the setting or their proximity to the plot goal. It could also be as simple as a bit of new information that shows another person in a new light. In order to truly move the plot, this information will not be incidental, but will affect how the character chooses to act in future scenes.

4. Examine the Scene for Complexity and SubtextOften, when a writer is struggling to make a happy scene interesting, the problem isn’t that the scene is happy, but rather that it is too simplistic. If your characters go to the beach to get ice cream and watch the sunset and it’s the best day ever, the end—that may be happy, but it’s also likely to feel flat.

Look for ways you can add layers of nuance and meaning to your story. How can this happy scene become a contrasting layer in a larger image, thereby adding to the story’s overall complexity? As mentioned, irony is a powerful tool toward this end. Also powerful is the potential mentioned in Elena’s original question and description of the story, at the top of the article. The description talks about how the characters’ happy moments are stolen against the backdrop of a difficult family situation. Even by itself, that’s complexity. These happy moments are not just happy moments; they are part of a larger conversation which they both inform and are informed by.

By the same token, dig deep for the subtext in even the happiest of scenes. What is being said on the surface of this scene? And what’s being said beneath the surface of this happiness? You may even find multiple contrasting messages all under the surface of the same scene.

5. Make Sure the Scene Is Bringing Something New to the StoryHappy scenes can often be reaction/sequel scenes in which characters integrate something that just happened from a more conflict-heavy segment previously. However, don’t forget that every piece of a story should contribute to the overall whole. This is important not just for structurally advancing the plot, but also because a sense that the story is progressing is what keeps readers engaged. They want to experience something new in every scene.

The good news is that if you’re aware of how your scene is changing the plot, then you are also probably aware of how the story has shifted enough to offer something new to readers (whether it’s a new character or setting, a new emotion or dynamic, or new information or perspective). Again, happiness doesn’t equal passivity. Happiness can include changes that are leisurely and contented, but it can also indicate changes that are hectic and deliriously joyous.

6. Make the Characters Earn ItFinally, one of the best tips for keeping readers engaged in your happy scenes is making sure they don’t feel self-indulgent. The truth is we all want to see characters happy. Happy characters usually make us happy. But if the happiness feels unearned within a story, it can strike a false note. Unearned happiness feels unrealistic and, ultimately, as if the author is either trying and failing at fan-service and/or indulging their own unearned desires to see their characters happy.

The happiest scenes in a story are often hard-earned by the characters. If you’re going to give them a piece of heaven, put them through a little hell first. The poignancy will be that much sweeter—not to mention more impactful to your plot and your character’s emotional arc.

***

Emotional scenes are some of the most enjoyable, both to write and to read or watch. How to write interesting happy scenes? As with all of writing, it really just comes to writing these scenes as authentically as possible, believing in the happiness you’re portraying, and showcasing it as part of the story’s larger pattern of cause and effect.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What’s your best tip for how to write interesting happy scenes? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Write Interesting Happy Scenes? 6 Tips appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

July 24, 2023

8 Different Types of Scenes

Any story will require many different types of scenes. Some of this variety will come from content (romance vs. action vs. humor vs. tragedy). However, much of the variety in types of scenes will arise from the needs of pacing.