Clifford Browder's Blog, page 9

August 7, 2020

473A. Pleasuring of Men

BROWDERBOOKS

Forgive this impromptu post, prompted by my inept attempts at BookBub ads (more about them in the next post).

Attention, all those interested in gay novels:

The e-book of my gay novel The Pleasuring of Men, the first title in my Metropolis series of historical fiction set in nineteenth-century New York, is available from Amazon Kindle for $4.99, marked down from $9.99. Tom Vaughan, the protagonist, is a high-priced male prostitute, and you'll never get him cheaper. BUT: This offer expires soon; if you want the e-book, get it here and now.

The Pleasuring of Men has been read and reviewed by as many women as men, and post cards with the front cover, when offered free at book fairs, fly off the counter. It's that sexy cover, of course. But Tom Vaughan makes the worst mistake a professional male prostitute can make: he falls in love a client. Worse still, with Walter Whiting, his most difficult client. Whiting is brilliant, knowledgeable, and sophisticated, which appeals mightily to Tom, but he is also moody and difficult. But once Tom knows what he wants, he goes after it, armed with wit, cunning, and persistence, and also with what. may be his greatest gift: his ability to listen. Tom's clients have included his mother's Episcopal minister, a rowdy young lawyer, a guilt-stricken Irish-American alderman, countless married men, and a European count who has him burst out of a cake naked at a party. But the one that counts is Whiting, elusive, troubled, and difficult.

I had hoped to exhibit The Pleasuring of Men and some other books at the Rainbow Book Fair, the annual gay book event at the Gay Center on West 13th Street, just a short walk from my apartment. Silas and I exhibited there last year and had some weird experiences, as reported in my post #432. But the Rainbow, in view of the pandemic, has been officially postponed until 2021.

I've also done a fictional interview with Tom; see post #320. A fun post; I should do more with other fictional characters from my books.

So much for Pleasuring, the Rainbow, and related matters. My next post, on how New Yorkers are coping with the virus, will be published next Sunday. Meanwhile stay safe, stay wise, stay healthy.

August 2, 2020

473. Apothecaries: Cocaine, Arsenic, and Opium, and All of It Just for You.

She's young, blond, and sexy, and promises marvels. Though Russian-born, in this country Alinka Rutkowska has adopted all the ways of enterprising capitalism and made herself a fortune. She's all over the Internet, promising to make authors the same kind of fortune that she has made for herself. Want to land on the USA Today bestseller list? She'll show you how. Stymied in your book marketing attempts? She'll help you attain remarkable success ... for a price. Two of her many books, bestsellers all: How I Sold 80,000 Books, Write and Grow Rich -- yours for only $2.99.

Have I had dealings with her? Yes, in a limited way. For a fee, I enrolled in her LibraryBub program, which supposedly made my first self-published title available to libraries, though I saw no notable increase in sales. Will I do it again? Yes, though at her bargain price, without expensive frills. So what do I expect? More exposure, a few sales, nothing more.

Why haven't I banished her to oblivion, as I have so many exploiters of aspiring and gullible Indie authors? Well, have a look at her online. She makes business sexy. Maybe it's her long blond hair. Or her enticing smile. I like her, she's fun. If nothing else, I keep her around for laughs.

A note on Goldman Sachs

Followers of this blog know the love I have for Goldman Sachs, which has been described as a vampire squid sucking profits out of everything it touches. Though I disapprove of the outfit, whose former execs have a way of infiltrating presidential cabinets, I can't help but marvel at its ability to feel out profits and suck them up. But Public Citizen has announced a signal victory: it has nudged the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) into issuing an order rejecting Goldman Sachs's denial of affiliation with a private equity company called Goldman Sachs Renewable Power. Investigating the names of this company's board members, Pub Cit found that the same three served on the boards of some 70 shell companies with ties to Goldman Sachs. After more digging, Pub Cit learned that the omnipresent trio work for companies based in the Cayman Islands that offer "directors for hire" to private equity shell companies for Wall Street. So for once, the vampire squid's behind-the-scenes attempt to control an allegedly independent shell company has failed. But this, I suspect, is just the tip of the iceberg. The vampire squid's tentacles reach everywhere and are rarely detected, as happened on this occasion, thanks to Public Citizen. (For more on the vampire squid, see post #340 and scroll down to "Goldman Sachs: The Vampire Squid Thrives On.")

APOTHECARIES:COCAINE, ARSENIC, AND OPIUM,AND ALL OF IT JUST FOR YOU

On an errand recently (properly masked), I went to my local independent pharmacy, Grove Drugs, and in the window I saw a conglomeration of objects that I recognized: old bottles of every size and shape, mortars and pestles, scales for weighing, dusty old books, and a massive volume, its pages open to reveal careful scribblings now indecipherable. I recalled seeing an almost identical display there three years ago, reported in post #309, which I am reproducing here, abridged. It takes us back to an earlier age when customers got individual remedies for their ailments.

CARDAMUMCAMPHORAMMONIUM CHLORIDEZINC OXIDEALUMRHUBARB AND SODA MIXTUREBELLADONNA

A row of time-worn books, one labeled Elements of Chemistry. Two thick, massive volumes brown with age, open to pages with scores of prescriptions affixed, scribbled in a near-indecipherable hand, their dates not visible, but probably from the early twentieth century. The whole display fascinating, puzzling, reeking with history and age.

Apothecary jars

Apothecary jarsSuch is the current window display of Grove Drugs, but a couple of blocks from my apartment. One of the few independent pharmacies left in the West Village, where chain stores dominate, Grove typically provides window displays of unusual interest, and this one fascinates. When I asked inside about the source of the earlier display, I was told that these objects had been found in the basement of the Avignone Chemists at Bleecker Street and Sixth Avenue, now closed, whose antecedents had gone back a century or more. Discovered during a renovation in 2007, these relics of the past might have been discarded but were preserved. Now, when displayed, they give us a glimpse of the pharmaceutical past, when the time-honored apothecary shop prevailed.

The profession of apothecary dates back to antiquity and differs from that of pharmacists today. Pharmacies today are well stocked with mass-produced over-the-counter products that come in standardized dosages formulated to meet the needs of the average user. But in earlier times the apothecary created medications individually for each customer, who received a product specific to his or her needs. In theory, the apothecary had some knowledge of chemistry, but at first there was scanty regulation.

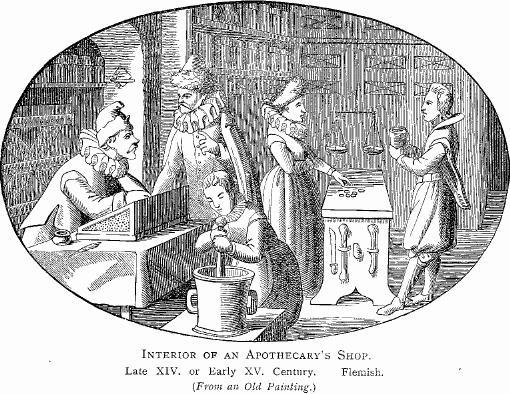

A Flemish apothecary shop, late 14th or early15th century.

A Flemish apothecary shop, late 14th or early15th century. A 17th-century German apothecary.Welcome Library

A 17th-century German apothecary.Welcome LibraryThe objects on display in Grove’s window hearken back to this early period when the apothecary made compounds from ingredients like those in the bottles and jars displayed, grinding them to a powder with a mortar and pestle, weighing them with scales to get just the right measure, or distilling them with the glass paraphernalia seen in the window to make a tincture, lotion, volatile oil, or perfume. The one thing typical of the old apothecary shops that the display can’t reproduce is the aroma, a strange mix of spices, perfumes, camphor, castor oil, and other soothing or astringent remedies. Mercifully absent as well from the Grove display is a jar with live leeches, since by the late nineteenth century the time-honored practice

The apothecary’s remedies were derived sometimes from folk medicine and sometimes from published compendiums. Chalk was used for heartburn, calamine for skin irritations, spearmint for stomachache, rose petals steeped in vinegar for headaches, and cinchona bark for fevers. Often serving as a physician, the apothecary applied garlic poultices to sores and wounds and rheumatic limbs. Laudanum, or opium tincture, was employed freely, with little regard to its addictiveness, to treat ulcers, bruises, and inflamed joints, and was taken internally to alleviate pain. But if some of these remedies seem fanciful, naïve, or even dangerous, others are known to work even today, as for example witch hazel for hemorrhoids.

But medicines weren’t the only products of an apothecary shop. Rose petals, jasmine, and gardenias might be distilled to create perfumes, and lavender, honey, and beeswax were compounded to create face creams to enhance the milk-white complexion desired by ladies of the nineteenth century, when the sun tan so prized today marked one as a market woman or farmer’s wife, lower-caste females who had to work outdoors for a living. (The prime defense against the sun was the parasol, without which no Victorian lady ventured outdoors.) A fragrant pomade for the hair was made of soft beef fat, essence of violets, jasmine, and oil of bergamot, and cosmetic gloves rubbed on the inside with spermaceti, balsam of Peru, and oil of nutmeg and cassia were worn by ladies in bed at night, to soften and bleach the hands, and to prevent chapped hands and chilblains.

But there were risks. Face powders might contain arsenic; belladonna, a known poison, was used to widen the pupils of the eyes; and bleaching agents included ammonia, quicksilver, spirits of turpentine, and tar. All of which suggests a lousy grasp of basic chemistry. And in the flavored syrups and sodas devised to mask the unpleasant medicinal taste of prescriptions, two common ingredients were cocaine and alcohol, which must have lifted the users to pinnacles of bliss.

Marketed especially for children.

Marketed especially for children.Also available in an apothecary shop were cooking spices, candles, soap, salad oil, toothbrushes, combs, cigars, and tobacco, so that it in some ways resembled the small-town general store of the time. And in the eighteenth century American apothecaries even made house calls, trained apprentices, performed surgery, and acted as male midwives.

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs window display, figures often in history and legend. It is said that Livia, the wife of the Roman emperor Augustus, used it to do away with her husband, so that Tiberius, her son by another marriage, could succeed him. And in folklore, witches used a mixture of belladonna, opium, and other poisons to help them fly to conclaves of witches called sabbaths, where participants did naughty things, danced wildly, and kissed the devil’s behind. The shiny black berries have been called “murderer’s berries,” “sorcerer’s berries,” and “devil’s berries.”

Belladonna, which appears in the Grove Drugs window display, figures often in history and legend. It is said that Livia, the wife of the Roman emperor Augustus, used it to do away with her husband, so that Tiberius, her son by another marriage, could succeed him. And in folklore, witches used a mixture of belladonna, opium, and other poisons to help them fly to conclaves of witches called sabbaths, where participants did naughty things, danced wildly, and kissed the devil’s behind. The shiny black berries have been called “murderer’s berries,” “sorcerer’s berries,” and “devil’s berries.”All in all, not a plant to mess with, although a staple in most apothecary shops. And if you think you’ve never gone near it, think again, for if you’ve ever had your eyes dilated, belladonna is in the eye drops. And the name is intriguing: belladonna, the beautiful lady who poisons. Which brings us back to the Empress Livia; maybe she did do the old boy in.

Given their lack of formal training and use of questionable ingredients, one may ask why, for centuries, apothecaries attracted a steady clientele. Because the only alternative was the medical profession, and prior to the nineteenth century they "cured" you by bleeding you or purging you, and in so doing sent many a patient to the grave. Mixing a medication meant specifically for you, apothecaries looked pretty good by comparison, probably killed fewer patients, and at times even managed a cure.

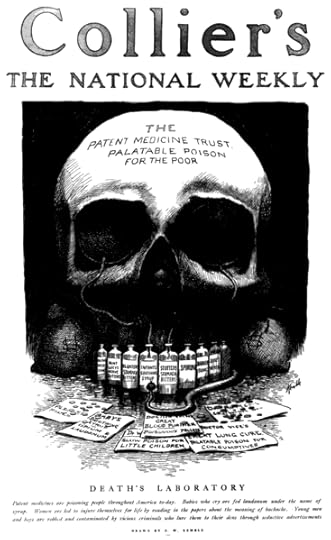

Gradually, the professions of apothecary and pharmacist -- never quite distinct – became more organized, and then more regulated. In the nineteenth century patent medicines (which were not patented) became big business, thanks to blatant advertising, but their mislabeling of ingredients and their extravagant claims finally resulted in the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. This and subsequent legislation probably benefited apothecaries, since mass-produced patent medicines competed with their products.

Collier's attacks the patent medicine industry.

Collier's attacks the patent medicine industry. As late as the 1930s and 1940s, apothecaries still compounded some 60% of all U.S. medications. In the years following World War II, however, the growth of commercial drug manufacturers signaled the decline of the medicine-compounding apothecary. In 1951 new federal legislation introduced doctor-only legal status for most medicines, and from then on the modern pharmacist prevailed, dispensing manufactured drugs.

By the 1980s large chain drugstores had come to dominate the pharmaceutical sales market, rendering the survival of the independent neighborhood pharmacy precarious. But in a final twist, the word “apothecary,” meaning a place of business rather than a medicine compounder, has become “hip” and “in,” appearing in names of businesses having nothing to do with medicines. As for a business that does indeed deal in medicines, a longtime pharmacy in the West Village calls itself the Village Apothecary. The word "apothecary" expresses a nostalgia for experience free from technology and characterized by creativity and a personal touch, a longing for Old World tradition and gentility. In other words, it's charmingly quaint. And as one observer has commented, “apothecary” is fun to say.

Coming soon: New Yorkers and the Virus: An Outdoor Baby Grand, a Naked Jesus, Free Haircuts, Mopeds, Bikes.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

July 31, 2020

brownstones

This is the best example I have of an 1860s Manhattan brownstone. Eliminate the flower boxes and A/C. They are imposing, but rather severe in style; no frills or curlicues, no balconies or bay windows. Steep stoops and tall ground-floor front windows. (Ground floor is the so-called parlor floor, reached by the stoop. Level with the street is the basement, which can also have front windows, but not tall like on the parlor floor.)

Turn-of-†he-century Brooklyn brownstones. Too ornate and too differentiated for 1860s Manhattan brownstones, rows of which can be similar in style. But see how the brownstones cluster together as row houses.

Brooklyn brownstones. But: in 1860s Manhattan, no bay windows. But a sameness of style for them all; no one stands out. No fire escapes in the 1860s.

More Brooklyn brownstones. But no bay windows in 1860s Manhattan. See how the whole row of them are similar in style; no one of them really stands out.

July 26, 2020

472. Bullies

The Brooklyn Book Festival is going to be held online, and for authors to participate will cost only fifty dollarooonies. So will I participate? No way! Author events can be done online, but book sales, never. What sells books (or anything) at a fair? Two things:Books on a table, carefully arranged.A steady flow of traffic to your table. Minus either of these, few sales. Minus both, none. So I'll keep my fifty smackeroonies for myself.

My next historical novel, Forbidden Brownstones, about an educated young black man in nineteenth-century New York, has been through two close readings by my in-house editor, and now, after a final third read-through, will go to a copyeditor.

Google Ads is now advertising my latest nonfiction title, New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You. I have launched two campaigns, the second slightly less inept that the first, and I have tried to add images to them, but with little control over formatting, which promises dismal results. Here is a photo from my 2019 book release party for The Eye That Never Sleeps that made it into my college alumni bulletin. A great photo, but Google, being fussy about dimensions, won't take it either as a rectangular image or a square one. The photos it does take are usually chopped up, captionless, and meaningless. I'm fed up with Google already. My solution: delete all the photos. If they can't be presented properly, they can go, and they are now gone.

(BTW: Read the sign in the lower left corner, if you can. When traveling by Greyhound bus in the West years ago, a refugee from Academia, I grabbed it out of a drab little hotel in Montana as a kind of souvenir. The misspellings are probably not legible here.)

Amazon won't let me advertise, and Google has the beginnings of a fiasco, so I will have to try something else. Not easy. With my local post office closed tight, at the moment I can't mail books myself. One possibility: BookBub. At least, I'll look into it.

For a post with all my books, go here. And for my new website, go here.

BULLIES

I hate them, always have, and my fictional characters hate them, too. This dates from my childhood. My first bully was my brother David, three years older than me. He was tall and dark, I was a blue-eyed blond whose hair soon turned to brown. In our early years, when he came at me, I didn't know if he would kiss me or hit me. What's scary is that he didn't know, either. He was a creature of impulse, with little thought of the consequences. There was an unspoken rule between us: if he only scared me, but didn't actually hit me, I wouldn't tell our parents. But in a park one day he heaved a brick at me, probably meaning to miss me narrowly. But he aimed too well: I went home screaming with pain, a big lump on my forehead. They rushed me off for an x-ray; luckily, nothing was fractured. What they did to my brother I don't know; I was too busy screaming with pain.

David was a rule breaker, always in trouble. How he must have, at times, hated little Hal, his blue-eyed brother, never in trouble, quite content if he could just quietly read a book and let it generate rich fantasies of life in another time. Sometimes David would leave me alone, and sometimes not. Once he got me so angry that I snatched up a letter opener from my mother's desk in the living room and flung it at him. Years later, when we were older and calmer, he told me that was the only time that I really scared him. I'd like to say that I hurled it with such force that it lodged in the woodwork inches away from his noggin. But no, I flung it rather gently and it clattered to the floor well short of him. But if the gesture scared him, that was something gained.

David was not the only bully in my life. Even a quiet, order-loving, respectable town like Evanston, the Chicago suburb where I grew up, abounded in them. Every block seemed to harbor one, always male, often the despair of his well-meaning parents. I had a few close brushes with several, but was never really abused. Then one late winter afternoon, trudging through a field of snow not far from my home, I was accosted by a kid somewhat younger than me, but tough. "I want to fight you," he said. With him was a friend, so it was two to one. I was older, but a glasses-wearing nerdy-looking bookworm, an easy target. "Well," I said, out of desperate bravado, "no better time or place." Fight or flight is the choice all creatures have, when in imminent danger; I chose flight. I raced off, but he easily overtook me, tackled me, and tumbled me down in the snow. Triumphant, he towered over me. "That's just some snow in your glasses," he said, and it's true that my glasses were filled with snow. "C'mon," he said to his buddy. "Let's not waste any more time with this sissy." And off they trudged, in search of more victories.

A third boy, a neutral, had witnessed this. With him watching, I got up, dusted the snow off me, wiped my glasses clean, and left. My flight had in fact accomplished my main goal: to be rid of the bully; perhaps I even let him tackle me. But when I got home, brooding alone in the living room, I burst into tears and wept for the next twenty minutes. I never told anyone about this incident, but the memory of it haunted me for years. My brother felt that only he had the right to bully me; if anyone else did, he would lay into them. But his reactions were so violent, that I knew not to trigger them. I preferred to keep my troubles to myself, even if they rotted my innards.

In fifth or sixth grade a kid named Hilliard had the habit of challenging me. I had in no way offended him, but he still greeted me, saying, "Hal, you're a sissy and I can prove it. I challenge you to a fight." "I don't want to fight," I replied. "See? You're a sissy." And he flashed a smug, triumphant smile. One day, as I was walking home from school, I came upon a bunch of classmates, one of whom, Billy, was in tears. "Hilliard punched him," explained the others, and in the distance I saw Hilliard sauntering off with his little brother. Everyone there sympathized with Billy, who had done nothing to provoke the attack. A glimmering of the truth began to dawn in me. If there was any kid in the class more vulnerable than me, it was Billy, a nice, quiet, harmless kid, immensely likable. Hilliard wouldn't challenge any of the tough boys in the class, he only went for me and Billy. In this instance, he was showing off for his little brother. Years later, of course, I realized that Hilliard, like my brother, was very insecure inside, and reassured himself of his manliness by bullying. Scratch a bully, and inside you'll find a scared little boy, profoundly insecure, desperate. I too was insecure, being a nerdy bookworm who hated sports, but I didn't take it out on others. Most of us don't; bullies do.

The Russian writer Solzhenitsyn, recounting his days in the Soviet Gulag, tells of how he once found himself lodged together with another prisoner, a big, muscular man who from the start made it clear that he was in charge. He ranted, he blustered, he bullied. So Solzhenitsyn stood up to him, quite ready to fight physically, if necessary. Challenged, the bully burst into tears. Solzhenitsyn was bullied no more.

Years later, when I realized I was gay, the question of proving my manliness, or hiding the lack of it, became irrelevant. I'm gay, I thought, I'm different. I don't give a damn about manliness. Let the straight guys worry about that. And worry they do, many of them. My e-mail SPAM folder is crammed daily with offers of promised hardness and secrets for seducing women, presumably addressing just such an audience of would-be Don Giovannis.

Can a woman be a bully? Once, long ago, when I was a freelance editor, I had a temporary desk on the East Side in a building owned by Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. On the same floor near me was the rented office of an agent, whose assistant worked there with two young people, a boy and a girl in their twenties. The agent was never here, but her assistant lorded it over them. "I expect you to take manuscripts home every weekend and read them. I want results, or else. This is no idle warning." So she expected them to give up a good chunk of their weekend, without additional pay. The two kids looked cowed, intimidated. Yes, women too can be bullies.

Many a CEO is a bully; I've heard stories of it all my life, and seen films about it, too. They get results, but at a price. Cult leaders too can be bullies, though in a subtler, more insidious way. As for politicians, need I say more? His inability to take criticism or admit faults, his speedy dismissal of those who don't kowtow, his twittering rage at his enemies -- all these I take as signs of a bully. If he isn't successful next November, he will fall into even more erratic rages, mouthing wild accusations and counter-truths, promoting a world of fantasies to shield him from reality. A bit like Hitler, who in his last days in the bunker lapsed in fantasy, ordering nonexistent divisions into battle, and proclaiming to the very end, "What I have tried to do for the German people!" Such was his state of mind, even as Soviet troops approached, Berlin lay in ruins, and the only solution for him was suicide. In the long run, bullies don't fare well. There are exceptions -- certain CEOs -- but usually time is against the bully.

Why do bullies do what they do? I have suggested deep insecurity. But maybe the real reason is simply, because I can. Which would explain a lot of evil in the world, if explanation it is. Because I can. Scary.

Coming soon: Apothecaries: Cocaine, Arsenic, and Opium, and All of It Just for You.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

July 19, 2020

471. Dangerous Falls

I am now advertising with Google ads -- a new experience fraught with risk and hope. Risk because I'm new to it, have to learn such esoteric terms as PPC (pay per click), KPI (key performance indicator), and ROI (return on investment), and am blundering ahead, confident that one learns by doing. Hope because every time someone clicks on my ad, they will be transported to my new website's HOME page, where New Yorkers is featured, with a brief description and links to Amazon and Barnes & Noble. At last report, 20.4K impressions, 55 clicks, but 0 conversions. So the ad has been shown 20,400 times, 55 people have clicked on it, but no one has bought the book. Well, it's early in the month-long campaign, so who knows? And I'm launching a second campaign with a much better set-up, based on what I've learned so far. Again, hope. Good old battered but resilient hope.

When my newly created Google ads account disappeared from my computer screen, taking my campaign with it, I consulted a Google technician to recover it. We worked all Thursday afternoon without results, then resumed on Friday morning and finally recovered it, but by then I was utterly worn out. A closing upbeat note: the technician said he had gone to my website, discovered New Yorkers, and is buying the book.

DANGEROUS FALLS

Friends and blog followers who responded to the story of my fall, which toppled a bookcase, gave me such interesting, albeit alarming, accounts of falls of their own, that I decided to do a post on falls, including, with their permission, their own. Here are their stories. Understandably, most of these falls occurred to older people, though not all the falls are age-related; one can fall at any age, and for any reason.

A friend in Florida, retired, told me of three separate falls.

As recommended by his podiatrist, he was wearing a protective boot on his right foot. The boot caught on the leg of his bed, and down he went on the hard tile floor. His left shoulder was injured and hasn't been the same since. He can't raise his left arm.While taking a nap on his bed, in his sleep he rolled off the bed onto the floor. No damage, just a startled awakening. Now, when napping, he makes sure he doesn't lie near the edge of the bed.On another occasion, after taking a few sips of his first cocktail, he wandered out into his back yard (he lives in a duplex), set his drink down on a table, and walked over to a fence to say hello to his neighbors, who were sitting on their side of the patio. Suddenly, to their astonishment, he keeled over. Fortunately, he landed on the grass, and not on the brick pavement he was standing on. No damage, but a mystery: not intoxicated, no dizziness, so why the fall? Was he tripped by the slightly uneven brick pavement? He has yet to figure it out.

With three falls in the last two years, he is concerned. Fortunately, there is a fire station nearby, so a 911 call brings them promptly to help him get back on his feet.

Another friend tells me how, just after she retired from teaching, she was crossing 72nd Street at Third Avenue one afternoon, when she slipped on some gasoline spilled out on the street and fell on her right shoulder. The resulting pain was so intense, she knew she had a serious injury. Hailing a cab, she rushed to the Lenox Hill Hospital emergency room, where she was luckily seen at once. X-rays revealed a fracture in the rotator cuff, but she was having guests over for dinner that evening, so she went home. The following day she phoned her internist, who recommended a surgeon at Mount Sinai Hospital, and she had surgery on the shoulder. When she told me this, I had never even heard of a rotator cuff, but some quick online research describes it as a group of four tendons connecting the shoulder muscle to the shoulder bone. Injuries here are not uncommon, especially if one falls on one's shoulder. Once again, I realize how lucky I was in falling: the bookcase got all the damage; I had only a slight scratch. But my friend was lucky, too. After surgery she worked with a physical therapist and fully recovered, except for occasional pain, if it is about to rain. Then, when it rains, the pain goes away.

Another older friend, who lives in Massachusetts in a house with four acres of grounds around it, tells how, when moving an art work to get things out of the way of a flood, he fell against it and demolished it. He and his partner are aware of the risks of falling, seem to get clumsier as they age. Well, who doesn't? Join the club.

Another really serious fall was told me by a friend who lives here in Manhattan on the West Side. She had been taking photos of the sunset from a window in her apartment, then went to bed. Later, she got up to get something from the kitchen, and went there in the dark, thinking she knew the way. But she forgot that she had moved an ottoman in the living room. Tripping over it, she fell on the hard stone floor. She lay there for a while, aware of broken glass, blood, and a bruised face. She thought of calling her neighbors, but in time got up, cleaned up the floor with towels, and got dressed, in case she needed to go to an ER. Instead, she stayed up all night, icing her head, and contacted her children the next morning. With a bruised face that hurt, she didn't go out in public for a long time, and to this day has a scar in her eyebrow. She threw out the ottoman, and now has night lights on. Still haunted by the memory of her fall, she relives it and talks to herself about it.

Yes, my bookcase fall was minor, compared to some of these stories. But I've had other falls, too. I can remember tripping on something and falling on the sidewalk near a restaurant with tables outside. Diners at the tables gasped, then asked if I was all right. Uninjured, I got up quickly and assured them, "I'm fine. I always bounce back." In those days I did.

Another of my falls resulted not from age, but from carelessness. This was years ago, when Bob was out of the city, and I was home alone. To access something on a high shelf in my bedroom, I stepped up on a wooden boxlike structure enclosing a radiator. The insecure surface gave way, and I tumbled down on the floor. Stunned, I just lay there for a few minutes, aware of bruises. The best thing I could do, I ecided, was to get to the bed and lie there quietly, taking deep, regular breaths. With effort I got up, took a few wobbly steps to the bed, and lay down. After fifteen minutes of rest and quiet breathing, my mind cleared, and I was fine. A bruise or two, but nothing else. Ever since, I have been careful, very careful, where I step. Lying quietly while taking deep breaths has always been my short-term solution for physical mishaps. It lets me clear my head, so I can deal with the situation.

About three years ago, crossing the street in daylight, I fell and hit my face on the hard pavement. No dizziness, so why I fell puzzles me to this day. No one else was around to help me up, but I managed to get back on my feet. I had a splotched purple face, a bruise or two, and a broken glasses frame (the lenses were intact), but no other injury. The splotch concerned me, for in two months I would be exhibiting at BookCon, the big two-day book event at the Javits Center here in Manhattan. A splotched purple face would be appropriate for science fiction and horror stories, but those genres I don't do, so I was concerned. But slowly, with time, the splotch receded, and I had a reasonably normal appearance for the event.

Yes, compared to some of my friends, my falls have not been serious. Painful, yes, and sometimes with bruises, but no lasting ill effects. But I know to be especially wary going downstairs and stepping off curbs. And where there is no railing, I don't venture.

Seniors are a stubborn bunch, often ignoring sound advice. When Bob was housebound with Parkinson's, the nurses and therapists who came to us had sad stories to tell of some of their elderly patients. "She has fallen three times," one therapist told us, "but she won't hire a home-care aide. She lives alone, and she's going to fall again. But there's nothing I can do about it." Yes, seniors can be stubborn, blindly and foolishly so. Let's be reasonable, clear-headed, and careful. We can't anticipate every problem, but we can have a plan in mind, should a problem suddenly arise.

Coming soon: Bullies.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

July 18, 2020

NYers cover

July 12, 2020

470. An Eye-Gouging Whodunit, Siegfried and Lance Armstrong

Good news: E.L. Marker, the hybrid affiliate of WiDo Publishing, has issued a press release announcing my signed contract with them to publish my next historical novel, Forbidden Brownstones. For the press release, go here. I'm now working on the manuscript with an in-house editor. I anticipate publication early next year, which is fine, since I hope to publish a new work every year. (Until I run out of unpublished manuscripts; four to go, this being one of them.)

This year's work, New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, was self-published and continues to get good editorial reviews (reviews by professionals), though not good reader reviews on Amazon. In fact, there is only one on Amazon to date, a 2-star review. I'm hoping there will be more, so as to balance that one out. Reviews can be short: a few sentences, one sentence, a phrase, a single word. So, readers, how about a review -- even a mini.

For New Yorkers and all my books, go here.

AN EYE-GOUGING WHODUNIT,

SIEGFRIED AND LANCE ARMSTRONG

Last time we did two of the five basic stories, The Journey and Boy Meets Girl. Now we'll do the rest. For the third, I propose

Whodunit

Of course this makes us think of Earl Stanley Gardner's Perry Mason, Agatha Christie's Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, Georges Simenon's Inspector Maigret, A. Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, and countless others. But I propose an ancient forerunner of them all: Sophocles' Oedipus Rex. Only the Greeks could come up with a whodunit like this. To save Thebes from a devastating plague, Oedipus, the king of Thebes, sets out to discover the killer of his father Laius. Slowly, relentlessly, the truth comes out: he himself is the killer; worse still, he has unwittingly married his own mother, Jocasta. Horrified upon learning this, Jocasta hangs herself, and Oedipus gouges out his eyes in despair. Sophocles' haunting comment at the end: don't account a man happy until the last day of his life. Oedipus was a happy, successful, and much esteemed ruler, but in the end he lost it all. For me, this is the whodunit of whodunits, impossible to top.

Oedipus, as presented in a Dutch production, ca. 1896.

Oedipus, as presented in a Dutch production, ca. 1896.A friend once told me of seeing Laurence Olivier in the role in a

double bill onstage. When Oedipus blinded himself, Olivier uttered a shriek such as the audience had never heard; it haunted them throughout the intermission. Then, in the second play of the evening, Olivier came on as a Restoration fop, glib, silly, and amusing; coming right after Oedipus, it was the most astonishing transformation conceivable. And for my friend, a veteran theatergoer, the most brilliant and unforgettable performance that he had ever experienced.

For the fourth basic story I suggest

Travails of the Hero

"Travails"? Why not "Troubles" or "Problems"? "Travails" sounds a bit hifalutin. Exactly: I want hifalutin.

To be a hero -- or heroine -- one has to have obstacles to overcome, monsters to slay, villains to defeat. Assuming, of course, that the story ends in triumph. In the Iliad Achilles, wronged by the Greek leader Agamemnon, broods in his tent, allowing the Trojans to drive the Greeks back to their ships; only when Patroclus, his best friend (and lover? Homer doesn't quite say) is slain by Hector, does Achilles go forth to confront and kill Hector. A triumph? Yes, but... (With the Greeks, there is always a "but..."). It has been foretold that, if Achilles kills Hector, his own death will soon follow.

Achilles and Hector, a German engraving of 1518-1530.

Achilles and Hector, a German engraving of 1518-1530.But in the Iliad, it's just the two of them in the final confrontation.

Wagner's Siegfried would seem to be the hero of heroes. (Wagner and many a German thought so.). In Joseph Campbell's scheme of things, as presented in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the hero's task is often to slay a monster and rescue a maiden or claim a treasure. In the opera Siegfried, this sturdy young son of the forest kills the dragon Fafnir, and then pierces a ring of fire to waken the sleeping Brunnhilde, thus winning a double prize: Fafnir's gold and Brunnhilde's love. (She, by the way, is Siegfried's aunt, but let's not dwell on that.) In the story that follows, Siegfried forgets Brunnhilde, becomes engaged to another woman, and finally gets himself killed by the villainous Hagen. So once again, the hero's victory is temporary; in the long run, these guys don't do well.

Siegfried slays the dragon.

Siegfried slays the dragon.A U.S. book illustration of 1914, artist unknown.

Siegfried's hair is long; no barbers in the forest.

So how about the girls? Flaubert's Madame Bovary, stuck in a dreary provincial town and married to a well-meaning but oafish husband, fights against boredom through adulterous affairs and the purchase of luxury items on credit, and finally, overburdened with debt, takes arsenic and dies. Her plight so gripped readers that her frustrated romantic yearnings were given a name: bovarysme.

Ibsen's Hedda Gabler is another frustrated wife trapped in a loveless marriage. Her romantic yearnings prompt her to

urge a depressed but brilliant young scholar to commit suicide "beautifully"; when she learns that he died messily in a brothel, she herself commits suicide. A complex and perhaps baffling character, but one that has haunted the public ever since Ibsen's play was first performed.

The Swedish actress Gertrud Fridh as Hedda, 1964.

The Swedish actress Gertrud Fridh as Hedda, 1964.A haunting stare, and perhaps a troubled one.

When one thinks of Joan of Arc and Mary, Queen of Scots, two famous historical figures whose lives have often been retold in theater, novel, and film, one may well wonder if any female hero -- or any hero at all -- ever triumphs and survives. Hardly, it would seem. Henry VIII's aspiring second wife, Anne Boleyn, has been acclaimed by feminists for pushing as far as she did and almost getting away with it, but she ends up on a scaffold. No, at the moment I can't come up with a heroine who ends happily, in triumph. It seems to happen only in fairy tales.

Just as Joan of Arc saved France, the women of America

Just as Joan of Arc saved France, the women of Americacan save their country by buying war savings stamps.

A 1918 lithograph, a wartime inspiration of

the U.S. Treasury Department.

And the boys? Well, Shakespeare's Henry V defeats those silly French at the battle of Agincourt and then marries a French princess: triumph aplenty. (Though history belies the bard: the king killed his French prisoners, and was so foolish as to die young, leaving the throne to an infant son who became the pawn of his guardians. As for Agincourt, it was more than canceled out by Joan of Arc's remarkable victories. And who remembers Henry V anyway? A few history buffs. But Joan of Arc is renowned the world over.)

Why are triumphant heroes and heroines in such short supply? Do we know too much about them, or too much about life? With rare exceptions, to be heroic is to be riding for a fall. To be victorious is to soon be doomed. Witnessed by the hoi polloi, this humbling of the great is relished. We, the lowly, like seeing our betters dragged down to our level and below. It's justice, it's fate, it's democracy.

And today, few of our real-life heroes, commemorated in sculptures and the names of institutions, are doing well. In the South, statues of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis are being torn down, or at least quietly removed from public places, given their defense of slavery in our Civil War.

In the North, Teddy Roosevelt -- the San Juan Hill-assaulting hero of our mercifully brief Spanish-American War -- is being removed from its outdoor site at the Museum of Natural History in New York. Why? Because flanking his heroic pose on horseback are a black man and a Native American, whom he seems to dominate. Though progressive in many ways, Teddy was an avowed racist and imperialist, two personae that don't sit well with the public today.

Heroic Teddy, mounted, flanked by a Native American

Heroic Teddy, mounted, flanked by a Native American and a black man on foot.

LunchboxLarry

And Woodrow Wilson, a Virginian by birth, is having his name removed from the School of Public and International Affairs, and from a residential college, at Princeton, because as U.S. President he segregated the civil service, which had been racially integrated for years. Yet he was hailed by crowds in post-World War I Europe as a champion of peace and the League of Nations, a forerunner of the U.N. It's no easier being an apparent hero in real life than in myth and literature.

"Uneasy rests the head that wears a crown" (Henry IV, Part 2), and that crown can be symbolic as well as real. Crowns have a way of slipping off or being snatched away. The American cyclist Lance Armstrong won an unprecedented seven Tour de France races in a row (1999-2005), but in 2012 was stripped of his wins when accused of having taken performance-enhancing drugs. Even I, usually uninterested in sports, became fascinated by his exploits ... for a while. His very name conveyed heroic power. I was well aware of the Tour de France, for when hitchhiking in France in the summer of 1952 I was overtaken by it. Hitchhiking became impossible, so I sat at the side of the road and watched the cyclists whiz by. But when, years later, Armstrong was dethroned, I conceived a skepticism about all athletic triumphs that is with me to this day.

Lance Armstrong in the Tour de France, 2009.

Lance Armstrong in the Tour de France, 2009.Pills or no pills, the guy displayed heroic effort.

McSmit

Even George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, long revered among the Founding Fathers, are somewhat suspect, having been slave owners. Will they too be dethroned? I doubt it. Rename the city of Washington, D.C.? Unthinkable. And the Jefferson Memorial in that city? Unlikely. One has to compromise at times. We need heroes, can't do away with them all.

So much for heroes. But how about comedy? What are we to do with Molière's Monsieur Jourdain in Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme? His deluded attempt to imitate the gens de qualité makes him light, fluffy, and laughable -- the very opposite of heroic. So it is with most of Molière's characters, so blindly and foolishly out of step with the reality of their times. So finally I propose

The Fool Exposed

The hero is not a fool; if he were, we couldn't cheer her on or lament his sad end. The fool so goes against reality that we laugh; satire is, by definition, laughter that rebukes. But there are exceptions -- above all, Tartuffe, one of Molière's most brilliant creations, a cunning hypocrite who is anything but laughable. It is his dupes, Orgon and his mother Madame Pernelle, good pious Christians, who are made to look foolish, if not quite laughable, and that got Molière in trouble. (He had difficulties in getting the play produced for the public.)

Shakespeare's Falstaff, a superb comic character, is not a fool to be laughed at. He is old, lustful, gluttonous, and a hearty drinker, but his boundless appetite for life enlists our sympathy. We laugh with him, not at him. If we must classify him, he is a hero, even if a coward on the battlefield. He loves life too much to be heroic.

And Cervantes' Don Quijote, is he a hero, or a fool to be exposed? Maybe a bit of both. I would have to have another look at the work to be certain. But great comic characters are often hard to classify, which speaks well for the authors who created them. We humans are complicated, riddled with ambiguities. Which makes us interesting. Some of us, at least.

Coming soon: Apothecaries: cocaine, arsenic, opium, and devil's berries, and all of it just for you.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

July 5, 2020

469. The Five Basic Stories of All Time

My nonfiction title New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, has been reviewed by Publishers Weekly. Since it is a self-published work, this is almost unheard of. And a good review at that, even if they dropped a word from the title.

It has also been reviewed favorably by a Hindi blogger whose English is less than perfect. But that review is welcome, too, since there is a market for English-language books in both India and Japan. I count on IngramSpark to make the book available abroad, and on Amazon to sell it in the U.S. That's how it works, if you self-publish.

For this and all my books, go here.

THE FIVE BASIC

STORIES OF ALL TIME

The idea came to me long ago, when I read somewhere that there are only five basic story types, repeated endlessly with variations, and that one of these is The Journey. Well, why not? One immediately thinks of Homer's Odyssey and Odysseus of Many Wiles (as Homer describes him), who spent ten years voyaging in the Mediterranean in an effort to return to his home, Ithaca, and his wife, Penelope. And Virgil's Aeneid, where Aeneas, fleeing the destruction of Troy, heeds the gods' inspiring him to go to distant Italy and found the race that will create the city of Rome, destined to rule the world -- at least, the known Western world.

Aeneas in a storm. A Dutch engraving of 1737. Dido / Britannia on the right; Neptune with his trident in the sea; overhead, three boys representing the winds: one blows, one kicks a hat, and the less said about the middle one, the better.

Aeneas in a storm. A Dutch engraving of 1737. Dido / Britannia on the right; Neptune with his trident in the sea; overhead, three boys representing the winds: one blows, one kicks a hat, and the less said about the middle one, the better.Odysseus's journey is a personal one, spiced up with encounters with the witch Circe and the seductive nymph Calypso, with whom he lingers on the island of Ogygia for many years. Aeneas's journey, on the other hand, is a mission willed by the gods (some of them) and opposed by others (especially the wrathy Juno) with the fate of the Western world at stake. And if Calypso diverts Odysseus from his homeward journey, Dido, queen of Carthage (Rome's future antagonist) likewise diverts Aeneas, though only briefly; abandoned by him, she dies on a funeral pyre whose smoke Aeneas sees from a distance, uncomprehending, as he heads for Italy. These journeys were not easy, and someone always pays a price.

Odysseus, strapped to the mast, hears the song of the Sirens,

Odysseus, strapped to the mast, hears the song of the Sirens, which entices seafaring males to their destruction. Their ears plugged,

his men row on, ignoring his deluded pleas to be set free. He is

determined to be the only man to hear the Sirens' song and survive.

From a fifth-century BCE Greek vase.

Journeys less epic are related in Jack Kerouac's On the Road (1957), a Beatnik classic, and John Steinbeck's Grapes of Wrath (1939), which takes the Joads family from the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma to the promised paradise of California, which turns out to be less than God's country. Of Kerouac's story, I chiefly remember he and his friends reveling noisily in a Mexican whore house, to the amusement of the locals. Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days (original French edition, 1872), which I know from the memorable movie of 1956, is another example, and some would add Huckleberry Finn's trip down the Mississippi. And come to think of it, let's add Melville's Moby Dick, relating Ahab's frenzied and doom-destined pursuit of the monstrous white whale. The Journey can be a mission, an escape, a diversion, a search for God's country, or a pilgrimage. And it can end joyously, sadly, or disastrously, thereby offering a lesson of some kind to the reader.

The famous balcony scene.

The famous balcony scene. An 1867 lithograph for Gounod's opera.

But the most obvious basic story, one that surely comes to everyone's mind, is Boy Meets Girl, with its necessary modern variations of Boy Meets Boy / Man, and Girl Meets Girl / Woman. Of these there are many examples, prominent among them Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, Anthony and Cleopatra, and even Midsummer Night's Dream, since it includes the troubled relationship of Oberon and Titania. The Brits have also given us Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre and Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights, the latter so melodramatic that it makes her sister Charlotte's eminent work look tame. Other examples: Goethe's Werther and Colette's Chéri and La Fin de Chéri, reminding us that these love stories don't always end happily; both Werther and Chéri commit suicide.

The lovesick Werther. Alas, the lady is

The lovesick Werther. Alas, the lady isa married mother and faithful to her husband.

An Italian painting, no date, inspired by Goethe's novel.

Oddly enough, I can't think of any American play or novel to add to the collection. Surely there are some. Why do they escape me? Well, here's one: my historical novel The Pleasuring of Men (Gival Press, 2011), a prime example of Boy Meets Man. But honestly, I didn't plan this so as to promote a novel of my own. (Yes, I hear the cynical titters and almost discern the knowing winks. But honestly...)

So much for two of the five types of stories. I'll add the rest in my next post. Can you guess what they might be?

Coming soon: Oedipus and Siegfried, Hedda Gabler and Lance Armstrong, Joan of Arc and the women of America. Not to mention Falstaff, Teddy Roosevelt, Achilles, and Tartuffe.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

June 28, 2020

468 COVID-19: How New Yorkers Cope

I have just signed with E.L. Marker, a hybrid offshoot of WiDo Publishing, to publish Forbidden Brownstones, the fifth title in my Metropolis series of historical novels set in nineteenth-century New York. It will probably be published early next year. "A hybrid?" you may ask. "What's that?" It's a set-up where the author gets the services of an established small press for creating and marketing his book, but the author has full control. This is what they offered, and it is just what I want. My current small press will probably terminate me when the contracts for my two books expire on September 30, in which case all rights will revert to me. So be it; I'll make other arrangements. But with a hybrid contract, no one can terminate me but me, myself, and that's now how I want it. I have full control.

Next: two more historical novels in the series, and then the big one: Metropolis (that word again!), a vast, sprawling, kaleidoscopic work, four novels in one, covering New York City from 1830 to 1880. But don't hold your breath, as it may never get published, unless I publish it myself. And will I even have time, given all my other projects?

I will soon do a media release announcing (at last!) my new website, with links to the most interesting (and sometimes controversial) posts in this blog over the years.

COVID-19: How New Yorkers Cope

New Yorkers have always congregated on stoops and fire escapes, and in the street in front of their apartment building or home, to communicate. In other words, to gossip, to chatter, to blab. Not all New Yorkers, to be sure. Nineteenth-century middle-class New Yorkers lived in handsome brownstones and would never have been caught sitting on their steep front stoops. Those stoops set them off from the hoi polloi, and were to be used by family, visiting ministers, and other callers of distinction; tradesmen, deliverymen, and servants were relegated to the basement entrance beneath the stoop. And all the other city residents? They usually didn’t have stoops, but they communed on rooftops and later, once such fixtures were mandated, on fire escapes.

When, en route to Europe, I first came to New York in September 1951, I walked west on West 43rd Street to the docks, to do some pre-voyage business with the French Line, whose pokey-slow liner the de Grasse would get me to Le Havre in less than record time. Going down the street, I was amazed at the crowds of working-class women and their kids gathered on and near the stoops of the houses. A child of the suburban Midwest, never had I seen so many people crowding around the entrance of a building. And they were loud. I recall one mother yelling to another that one of her kids was doing something he shouldn’t be doing, causing Mom to immediately intervene. The husbands were of course at work. And the fact that these residences had stoops bears witness to their having come down in the world. In this neighborhood, at least, gone were the days when the middle class called them home.

So the stoop and the nearby street have always been a part of New York living, and today they characterize both middle-class and working-class neighborhoods in all five boroughs. But this is the time of COVID-19. With the city in lockdown, and people in masks maintaining social distancing in fear of the virus, are the stoops and fire escapes and sidewalks deserted? No way! They are a vital part of New York living, and are chronicled as such in a two-page spread in the Sunday Times of June 14, 2020. Featured are short accounts from all five boroughs of how New Yorkers of all classes are coping. Specifically, how they are communicating with their neighbors. For instance:

Early April: a man living on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, on the second floor of a building facing Central Park West, chats from his window with friends passing by, including a gifted decorator, a cyclist who rides in the park, and a neighbor walking her dogs. He also waves to a friend and her husband en route to Mount Sinai to give birth (it was a son).

A Puerto Rican man living in the Port Morris section of the Bronx, near the Bruckner Expressway, reports hearing planes taking off from La Guardia Airport, and also steady traffic on the expressway in spite of the lockdown. But he also hears his neighbors outside joking in Spanglish or salsa playing.

St. George, Staten Island: A woman asks the couple next door if they need anything, and half-joking, tells them not to ask for toilet tissue. Later that afternoon she finds on her stoop a six-pack of toilet tissue and two rolls of paper towels. “We have extra,” her friends next door explain.

Late April: A woman in Manhattan’s East Village lives in a deserted building, her neighbors having fled the city. But when 7 p.m. comes and New Yorkers celebrate first responders by making noise or music from their front windows, she welcomes the music from a tenement across the street, and a sign that two women there hold up: HOW YOU DOIN'? And when those windows go dark, she hears an electric guitar playing the Star-Spangled Banner, Jim-Hendrix style.

A woman in Jamaica, Queens, tells how every day a bunch of men, a few masked but most of them maskless, gather on her block to drink beer and chain-smoke on the sidewalk in front of their building, leaving the pavement strewn with cigarette butts. A few years ago their habitual catcalling so annoyed her that she confronted the main culprit, shook his hand, and asked him not to do it; after that he waved to her regularly and said hello. Now, when she walks by the same bunch in a mask, one shouts, “Keep the corona away!” and then adds, “But have a Heineken.”

A longtime super in a building in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, tells how his building, once alive with baby showers, barbecues, and baptisms, is now strangely quiet, as the residents stay indoors. Most are undocumented immigrants who lost their full-time jobs and have trouble paying the rent. But when a woman in her 70s gets sick, neighbors leave food by her front door. “For undocumented people,” the super’s wife says, “there’s no stimulus package.”

In a big housing project for low-income people in Red Hook, Brooklyn, the lockdown has made people tense. Then a shipment of 20,000 pineapples from Costa Rica arrives, donated by a container terminal down the street. Two women volunteers rent a U-Haul truck, load it with pineapples, and deliver them to nonprofits and low-income housing projects. People respond with photos of themselves drinking piña coladas and pineapple tea.

In Parkchester in the Bronx, a Latino piano player living in a two-story apartment building owned by his parents plays his piano on the front porch every morning at 11, after seniors’ privileged time at the local stores; even the mailman stops to listen. There is no tip jar, so neighbors leave bottles of wine on the porch.

In Manhattan’s Chinatown a volunteer neighborhood block association team of young men patrols on Mott Street as a deterrent to anti-Asian hate crimes. Says one volunteer: “It’s good for the soul.”

In Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, a third-generation Puerto Rican American and her children chalk inspirational messages on the of the stoop of the house where she lives with her grandparents. A photo shows the stoop and its messages:

HEY BROOKLYNLET’S MAKE SUREWE LISTEN, REFLECTTEACH OUR YOUNG (AND OURSELVES)KEEP A KIND HEARTJUST DO BETTERIN DARKNESS WE TRANSFORMIN LIGHT WE GROW

After each rain, a new quote appears.

June: On 28th Street in Astoria, Queens, front-line workers and others gather every night on the street, masked, for a beer, a smoke, or a chat. When a physical therapist tells of rotating hospital patients on ventilators, a doctor hands her a loaf of homemade sourdough bread, and the therapist offers him some fresh-picked rhubarb. Sharing experiences and food, they realize they’re all in this together, and prepare themselves for further challenges in their grinding daily work.

So it goes in New York today. I have ZOOMed now with friends three times, twice with New Yorkers and once even with friends in Lincoln, Nebraska: another way to communicate safely in the time of COVID-19. And strangers in the street greet me and wish me a pleasant day -- normally unheard of in New York, where there are simply too many strangers to acknowledge. But this is different: we're all in it together. New Yorkers are coping, and so, I'm sure, is everybody else.

Source Note: The content of the preceding

post is drawn from the article "There Stays the Neighborhood" in the Metropolitan Section of the New York Times of Sunday, June 14, 2020.

Coming soon: In all the world's art, myth, and literature, by my count there are only five basic stories, maybe six, endlessly repeated with variations. Can you guess them?

© 2020 Clifford Browder

June 21, 2020

467. Hot Mama: Goddess, Mother, Virgin, Whore.

For a lively three-star Reedsy Discovery review by Jennie Louwes of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, go here.

And for my other books, plus summaries and reviews, go here.

An aside: Those who follow this blog know what love I have for Goldman Sachs, the vampire squid of Wall Street, second only to my love for Monsanto, whose storied name, linked to diverse controversies, will now disappear, following its acquisition by Bayer in 2016. But to get back to Goldman: I have just learned that it has been involved in a scandal with 1MDB, a Malaysian sovereign wealth fund, whereby $2.7 billions in stolen funds were spent on luxury apartments, yachts, and diamonds. I will say for Goldman that even in its most dubious and nefarious dealings, it aims high: not $2.7 million, but $2.7 billion. And now, as usual, it is trying to avoid admitting fault, even though a former executive has pleaded guilty and is cooperating with the authorities. If Goldman is forced to admit guilt, it will be a shining first, for in all its dubious dealings in the past, it has never done so. And this is the outfit that has provided so many executives to administrations both Republican and Democratic; scratch our federal government, and you will almost always uncover a Goldman exec or two, usually in significant positions. For example, Steven Mnuchin, Trump's Secretary of the Treasury, who is still with Trump, though other Goldman alumni have left him, following disagreements in policy. Will the vampire squid at last be forced to admit guilt? Stay tuned. (For more on Goldman, see post

And now at last:

Hot Mama Goddess, Mother, Virgin, Whore

The gods are still with us insists the Italian scholar Roberto Calasso, one of whose highly acclaimed books I am now reading in translation, and I’m inclined to agree. For him, it’s especially the pagan gods of ancient Greece and Rome. I can grasp this, in a certain way. When we undergo a sudden rash infatuation, we’re at the mercy of Venus, or Aphrodite. If we feel the urge to make war and kill, Mars, or Ares, has hold of us. If a writer suddenly finds the needed words of a poem pouring into his head, Apollo and the Muses must be at work. Without believing literally in the existence of the gods, we can see and feel them as real in sudden moods and urges not otherwise explained. They are triggers in our psyche, murky motivators that sneak or wiggle or explode upon us. They explain things otherwise inexplicable; they are a part of us, mysterious but essential.

Am I visited by this pantheon of urges? Yes, like anyone, but the most basic and omnipresent of my gods is Hot Mama, of whom Venus or Aphrodite is only one of her many faces. Hot Mama takes many forms, all related; you can’t have one without the others. Where do I encounter her? In sudden moods and urges? Not really. In my dreams? Not that I’m aware of. Where, then? In my writing, especially, alas, poesy. (My preference for this word instead of “poetry” indicates a deep suspicion, verging at times on hostility, regarding the whole enterprise — a hostility that I in no way feel toward prose.) So let’s have a look at the many faces of Mama.

She is mother and goddess.

Here is Aphrodite or Venus, the Greek goddess of love and beauty, and Ceres or Demeter, the Greek goddess of harvest, fertilty, and agriculture. Also Freia, the Norse goddess of love, fertility, and beauty, and doubtless many more.

Venus before the Mirror, Rubens, 1612-1615.

Venus before the Mirror, Rubens, 1612-1615.That's Cupid holding the mirror.

Venus/Aphrodite appears in Western art as naked, sensual, and seductive, often on the hefty side, as in Titian and Rubens, that being the ideal of the day. But those hefty Venuses turn me off; their vast proportions could envelope you, smother you. “Aha!” a captious critic may declare. “You’re gay, so you must hate women!” Which on his part would be stupid, and ignorant as well. Gay men get along fine with hetero women, once sex and romance are ruled out, for that makes room for friendship. Romance lasts a year or two; friendship can last a lifetime. When Bob and I were together those many years, we had more women friends than men, and most of them were hetero. As for Venus in art, if the hefty ones turn me off, I find Botticelli’s Venus, seen in his marvelous painting The Birth of Venus, vastly appealing; svelte and modest in her nakedness, she is less Mama than Virgin. But for me, I repeat, vastly appealing.

The Birth of Venus, Botticelli, 1484-1485.

The Birth of Venus, Botticelli, 1484-1485.The mother goddess is a most necessary deity, given our need of fertility and harvests and grain. But she can be a great mischiefmaker as well, as witnessed by the Trojan War. When the goddess of discord hurled into a gathering of the gods an apple marked “For the fairest,” it was claimed by Heres, Athena, and Aphrodite (Juno, Minerva, and Venus), who asked Paris, the Trojan prince, to decide. Heres offered power, Athena offered wisdom, and Aphrodite promised him Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world. He went with Aphrodite, who helped him to abduct Helen, the wife of the Greek ruler Menelaus, thus provoking the ten-year Trojan War and the destruction of Troy. Let’s hope that Helen made him happy … for a while.

She is fertility and growth. For me, spring and summer are closely associated with gods. Spring is a naked young god flaunting his erection and causing buds to open, flowers to bloom, and roots to suck juices from the earth; he is brazen, fearless, and provocative. No particular traditional god, but any of them who matches this description.

Summer, on the other hand, is feminine: the mother and seductress, enticing, enveloping, smothering. I sense her in hot, muggy August, when many plants usually labeled “weeds” — white sweet clover, coneflower, burdock, pilewort, ragweed, and mugwort — grow rank and thick in fields and tower over me. Unless stopped by the cold weather of autumn, they seem about to take over the world, to embrace and suck and smother me. Just as, when hiking, I have seen them creep over abandoned cars in remote parklands and fields and ravines, where they embrace and smother them, reclaiming them for a relentless, insidious, and triumphant nature. This is Mama beyond nurturing and feeding and fertilizing; she can be cruel and lethal — an aspect that cultures other than our own have emphasized, as we’ll soon see.

So do I hate the summer? God no, I love it. I love its berries and harvest them. I love its weeds with their smooth or prickly stems and intoxicating fragrances, and the peppery or lemony or bitter taste of their leaves. I have come back from late-summer outings sunburnt and tired, thorn-scratched, my skin itchy with rashes, my whole being drugged with the fullness, the luxuriance, the too-muchness of summer. Summer entices, summer gluts, summer chokes.

She is violent, lethal, and horrifying.

It is cultures other than our own who plumb the dark depths of Mama. Those depths are seen in Coatlicue, the Aztec earth mother, with her necklace of severed human heads. Her name means “Serpent Skirt,” and she is seen as having a skirt of writhing snakes. She is the mother of the sun, the moon, and the stars, as well as of gods and mortals. As such, she is associated with the earth as both creator and destroyer, and the legends about her are full of violence and murder.

Coatlicue, National Museum of Anthropology

Coatlicue, National Museum of Anthropology and History, Mexico City.

El Comandante

Akin to her is Kali, the dark goddess of India, who has been worshiped over time as the Divine Mother and the Mother of the Universe. She is associated with sexuality and death, as well as with motherhood and mother love. Variously visualized, she usually has many arms and a dark or blue skin, her eyes red with rage, her hair disheveled, with fangs sometimes protruding from her mouth. She often wears a skirt of human arms, and like Coatlicue, a garland of human heads. If Coatlicue comes off as a bugbear and boogeywoman of nightmares, Kali is not someone you would want to meet on a lonely road at night. Yet her worshipers also see her as a benevolent mother who protects her children and devotees.

Kali, a 1770 print. Here she has four arms,

Kali, a 1770 print. Here she has four arms,and stands on her consort, Shiva, which

shows who's boss.

Somewhat differnt is Pele (pronounced PEH-leh), “the woman who devours the earth.” The Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes and fire, she dwells in the drizzle-shrouded crater of Mount Kilauea on the island of Hawaii, leaking smoke from fissures in the earth. Then, when she so chooses, she erupts with earth-shattering violence. Setting forests ablaze, she sends streams of lava down her slopes to make thousands of residents abandon their doomed houses and flee, until her lava pours into the ocean amid caustic fumes laced with fine specks of glass. “Pele is coming down to play,” say the Hawaiians. She is their grandmother, the creator of their island in all its stunning beauty, and must be indulged, appeased. She can appear in human form, so if you see her hitchhiking, be sure to pick her up, and since she has a weakness for it, offer her some gin. Like her descendants, she enjoys a little mischief, so if she destroys your home, shrug it off and build another. (For more on Pele, see my post #380, “When Grandma Burns Your House Down," and scroll down past another mischievous female, my partner Bob's onetime significant other.)

The goddess of fire, Pele, meets the goddess of the sea,

The goddess of fire, Pele, meets the goddess of the sea,Namakaokahai, as lava flows into the ocean.

Photo taken from a helicopter, July 31, 2018.

Anton

This fiery goddess does not trigger the horror inspired by Kali and Coatlicue. In my opinion, every people gets the gods that they deserve. The Jews of the Old Testament wanted a jealous and wrathy god, and they got one. The Aztecs and the people of India wanted a fearsome mother goddess who bought both life and death, and who filled humans with horror. But the Hawaiians are too gentle and too mischievous to worship such a deity; they got Pele instead: a loving but capricious grandma whom they can relate to. They worship her, fear her, respect her; she is primordial, yet of their own time and all too immediate. She cannot, must not be ignored.

She is lewd.

How could she not be, as the goddess of fertility and growth and too-muchness? Fertility is not concerned with morality and restraint, only with procreation, with the endless and unlimited increase of life in all its forms. “Increase and multiply,” God tells Noah and his sons (Genesis 9:7), and in this one matter my lady is true to the Bible. She is the wantonness in all of us, uncurbed and unashamed: sexuality, overt or hidden, without any need of Freud and his analysis. She is, in fact, inexplicable. She does, she never thinks; consequences are not her thing. A life-affirming, life-degrading slut.

She is virginal.

State one side of her, and its opposite pops up. Yes, she is a virgin too, the Madonna of Christianity, giving birth to the Savior who will redeem humanity from the curse of the temptress and enticer Eve, who, as Adam’s mate, is yet another mother of us all. The patriarchal early Christian church had no room for women, those temptresses and seducers, but the people did, and in time forced the cult of the Virgin on the Church. If you can’t lick ’em, join ’em, and that’s what the fathers did. Christ will judge us on the day of Judgment, sending some to heaven amd some to hell, but she will be there to plead for us and save all whom she can. She is wise, accessible, compassionate; she understands. How could a troubled and sinful humankind not worship her, praise her with litanies, light flickering tapers before her shrines, and build great Gothic cathedrals with exquisite stained-glass windows, and flying buttresses to lift their vaulted ceilings skyward. Don’t try to puzzle out the Virgin Birth, a theological conundrum devised by the fathers of the church, those logic-chopping explicators and system multipliers. Madonna needs no such guck. She is the holiest of mothers, our glory, and our hope.

Madonna of the Book, Botticelli, 1480.

Madonna of the Book, Botticelli, 1480.Like Rubens, Sandro preferred blondes.

So there you have it: my Hot Mama, who is goddess, mother, virgin, whore. Can you blame me for being obsessed with a figure so many-faced and complex, so deliciously ambiguous? She appears in my recently concocted poetry manuscript “Hot Mama and the Big Sneeze,” a morality play on steroids. Just as, in the old morality plays, heaven and hell fought for the soul of Everyman, so in this work Hot Mama, the First of the Red Hot Mamas, contends with the Big Sneeze, who may or may not be God, for control of the Hero, who has flat feet, wears glasses, and may or may not be Siegfried, Mickey Mouse, or us. But don’t worry, you won’t have to unravel these ambiguities, since no small press will be so foolish as to publish so reverently irreverent a mishmash of alleged poesy, especially when there is plenty in it to offend believers.

So now I've told you about my Red Hot Mama. What gods or goddesses do you have, and how do they affect your life? And don't say you don't have any, because we all do. So tell me, who do you worship? I dare you. But of course you won't: too busy and maybe too scared. It would say a lot about you, probably too much.

Coming soon: Maybe how New Yorkers communicate in and out of lockdown. Stoops, fire escapes, the street.

© 2020 Clifford Browder