Clifford Browder's Blog, page 10

June 14, 2020

466. Blood

BROWDERBOOKS

For a lively three-star Reedsy Discovery review by Jennie Louwes of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, go here.

As always, for my other books, go here.

BLOOD

“Blood!” exclaim Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, uttering their newfound watchword, in anticipation of a midnight foray into a cemetery where they will, in fact, witness a murder. (This, at least, is how it was in a children's theater version of the story that I saw long ago.)

Blood: The word conjures up all kinds of meanings and associations, some pleasant and some the very opposite. It can mean heredity. “Le bon sang ne ment pas” (good blood doesn’t lie) is a saying in French, used by the old nobility to talk up their superiority to commoners (i.e., you and me).

Blood is one of the four humors of medieval medicine, a notion that originated with the Greek physician Hippocrates (460-370 B.C.), considered the founder of modern medicine. The perfect balance of the four — black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood — supposedly guaranteed health. Furthermore, an excess of any one humor determined a person’s personality. Black bile made people melancholic (sensitive, artistic); yellow bile made them choleric (full of vitality, but quick to anger); phlegm made them phlegmatic (calm, open to compromise); and blood made them sanguine, meaning joyful and optimistic — a meaning that survives in the word today. So according to Hippocrates & Co., a bit too much blood isn’t a curse; what’s wrong with being joyful? If “blood” has a bad press, it’s not his fault.

Growing up, I was told by my parents to eat meat, because meat builds red corpuscles, and red corpuscles make one strong and healthy. I remember blood swabs recorded in the family doctor’s office, little splats of color smeared on cards year after year with a date. As I grew up, mine progressed from pink to deeper pink to red. But not because of red corpuscles, I suspect, for I loathed meat, wouldn’t eat it, was left alone at the lunch table for up to two hours at a time, staring at the cold chunks of meat that, even when warm, repelled me. My solution: I hid the uneaten bits of meat on a small ledge under the table and later removed them to my knicker pockets and from there to the trash. But once I forgot to empty my pockets, and my mother, preparing to send my knickers to the laundry, was amazed to find the pockets full of stale chunks of meat.

Blood is red, and the color red suggests fire and violence, an association reinforced in me more than once, upon seeing a whole building (not my own) engulfed in flames. Violence often means bloodshed, the taking of life, which in most people inspires a feeling of horror. One major exception: hunters view the shedding of animals’ blood as normal; it’s simply part of the game. My father was a hunter, and he explained to me that hunting is an instinct, stronger in some people than in others. He was a hunter; I was not. He taught me at age sixteen to shoot a shotgun, but the gun's recoil gave me a shoulder ache, and I had no desire to kill the blackbirds flying overhead, or the rabbits scampering through brush, that were the targets of our shotgun outings. I didn’t even relish fishing, and winced when my father occasionally caught a fish that then flopped about in panic on the floor of our rowboat, until he bashed it against the side of the boat. No blood, perhaps, but violence nonetheless.

In the Russian Revolution the Bolsheviks were designated “Reds,” and in fact were quite willing to shed blood, to kill, if they deemed it necessary. And not just the Czar and his family, but even fellow revolutionaries, if they challenged Lenin’s authority.

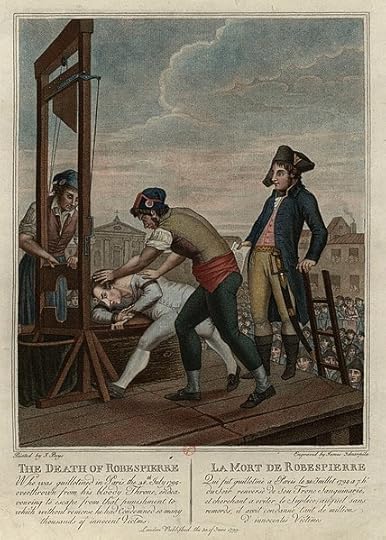

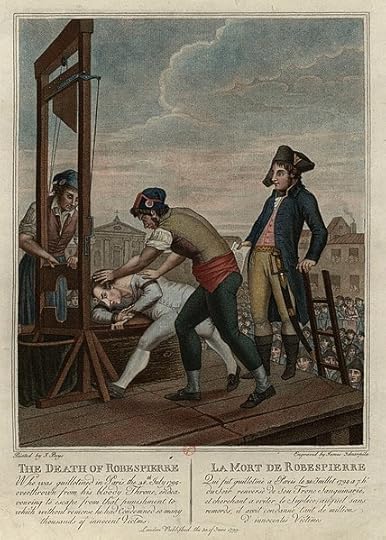

The French Revolution found a means of executing efficiently en masse: the guillotine. It shed blood, but ended life with one quick stroke, therefore was deemed, in its way, humane. But the horror of the revolution’s violence is well summed up in prints showing the executioner holding up the severed head of Louis XVI to a cheering mob. Scenes such as this inspired Tennyson, very English and very conservative, to deprecate “the red fool fury of the Seine.” Ironically, the king’s failure to hold the revolution in check at an earlier stage was due to his refusal to have his troops fire on the people; he abhorred bloodshed.

Robespierre's death by Madame

Robespierre's death by Madame

la Guillotine, July 28, 1794.

His death marked the end of the Reign of Terror.

A French engraving, circa 1799.

Ecclesia abhorret a sanguine (the Church abhors blood) was a tenet of the medieval Christian Church, but that didn’t keep the Inquisition from sentencing heretics to death. Granted, death by fire — by being burned at the stake — might not involve bloodshed, but the Church avoided the violence of executions by handing its victims over to the secular authorities, who nursed no such hypocritical reservations. And merry bonfires there were, and well attended, with the victims sometimes crying out, “More fuel, good people, more fuel!” in hopes of speeding up their death. If the wind was wrong and the fire burned slowly, what was usually a half-hour torment could stretch out to a full two hours.

Chained heretics burned at the stake.

Chained heretics burned at the stake.

Date and source unknown.

Yes, bloodshed is abhorrent. The ultimate in horror is attained when a psychopathic killer drinks his victim’s blood. Yes, such acts have been recorded, and the offender isn’t a fictional creation like Dracula; he’s very real. (Yes, usually a man.). But these are individual psychopaths, not typical of society. And yet, in wartime one may wonder. Wartime films rarely survive into peacetime. I recall a film from World War II in which an Australian civilian showed his righteous rage and patriotism by choking a Japanese soldier to death. I can’t imagine it being shown in peacetime; it would be … yes, abhorrent.

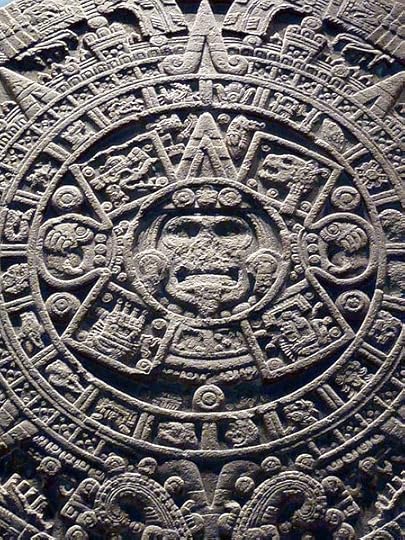

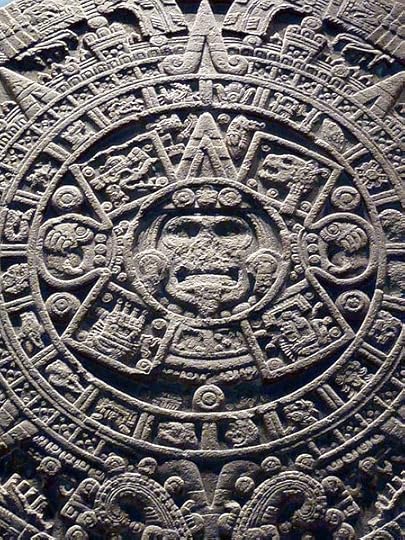

But what if a whole society thinks that its survival depends on drinking human blood? Such was the Aztec belief. Only the sacrifice of human blood gave strength to the sun; without it, the sun would be overtaken and destroyed by the pursuing forces of darkness, causing the extinction of the human race. On prominent display in the National Anthropology Museum of Mexico City is the Aztec Calendar Stone, also known as the Aztec Sun Stone, a heavy circular stone close to 12 feet in diameter and 39 inches thick. When I saw it there many years ago, I was overwhelmed. Thinking that maybe, on this very stone, human sacrifices had once been performed, I felt both chilled and fascinated.. This may have been my overwrought imagination at work, but the stone is certainly linked to sacrifice. In its very center is a god holding a human heart in each of his clawlike hands, his protruding tongue in the shape of a sacrificial knife.

Rob Young

Rob Young

Depending on the state, in this country we allow the death penalty for certain crimes, but in modern times we don’t want blood to be shed. Too gross, too icky. So we shun the guillotine and try everything else: the electric chair, which sometimes has the victim twitching in agony; hanging, which sometimes leaves the victim likewise writhing in agony; and the gas chamber, a ”scientific” contraption that also lacks the quick finality of Madame Guillotine. No matter how you go at it to avoid the shedding of blood, it’s messy, and often downright cruel. I hadn’t anticipated ending on this note, but here indeed we are. Messy as they are, the guillotine and the stroke of an ax are mercifully quick and definitive.

Coming soon: Hot Mama: Goddess, Mother, Virgin, Whore. Not, in any conventional sense, a hymn to motherhood.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

For a lively three-star Reedsy Discovery review by Jennie Louwes of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, go here.

As always, for my other books, go here.

BLOOD

“Blood!” exclaim Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, uttering their newfound watchword, in anticipation of a midnight foray into a cemetery where they will, in fact, witness a murder. (This, at least, is how it was in a children's theater version of the story that I saw long ago.)

Blood: The word conjures up all kinds of meanings and associations, some pleasant and some the very opposite. It can mean heredity. “Le bon sang ne ment pas” (good blood doesn’t lie) is a saying in French, used by the old nobility to talk up their superiority to commoners (i.e., you and me).

Blood is one of the four humors of medieval medicine, a notion that originated with the Greek physician Hippocrates (460-370 B.C.), considered the founder of modern medicine. The perfect balance of the four — black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood — supposedly guaranteed health. Furthermore, an excess of any one humor determined a person’s personality. Black bile made people melancholic (sensitive, artistic); yellow bile made them choleric (full of vitality, but quick to anger); phlegm made them phlegmatic (calm, open to compromise); and blood made them sanguine, meaning joyful and optimistic — a meaning that survives in the word today. So according to Hippocrates & Co., a bit too much blood isn’t a curse; what’s wrong with being joyful? If “blood” has a bad press, it’s not his fault.

Growing up, I was told by my parents to eat meat, because meat builds red corpuscles, and red corpuscles make one strong and healthy. I remember blood swabs recorded in the family doctor’s office, little splats of color smeared on cards year after year with a date. As I grew up, mine progressed from pink to deeper pink to red. But not because of red corpuscles, I suspect, for I loathed meat, wouldn’t eat it, was left alone at the lunch table for up to two hours at a time, staring at the cold chunks of meat that, even when warm, repelled me. My solution: I hid the uneaten bits of meat on a small ledge under the table and later removed them to my knicker pockets and from there to the trash. But once I forgot to empty my pockets, and my mother, preparing to send my knickers to the laundry, was amazed to find the pockets full of stale chunks of meat.

Blood is red, and the color red suggests fire and violence, an association reinforced in me more than once, upon seeing a whole building (not my own) engulfed in flames. Violence often means bloodshed, the taking of life, which in most people inspires a feeling of horror. One major exception: hunters view the shedding of animals’ blood as normal; it’s simply part of the game. My father was a hunter, and he explained to me that hunting is an instinct, stronger in some people than in others. He was a hunter; I was not. He taught me at age sixteen to shoot a shotgun, but the gun's recoil gave me a shoulder ache, and I had no desire to kill the blackbirds flying overhead, or the rabbits scampering through brush, that were the targets of our shotgun outings. I didn’t even relish fishing, and winced when my father occasionally caught a fish that then flopped about in panic on the floor of our rowboat, until he bashed it against the side of the boat. No blood, perhaps, but violence nonetheless.

In the Russian Revolution the Bolsheviks were designated “Reds,” and in fact were quite willing to shed blood, to kill, if they deemed it necessary. And not just the Czar and his family, but even fellow revolutionaries, if they challenged Lenin’s authority.

The French Revolution found a means of executing efficiently en masse: the guillotine. It shed blood, but ended life with one quick stroke, therefore was deemed, in its way, humane. But the horror of the revolution’s violence is well summed up in prints showing the executioner holding up the severed head of Louis XVI to a cheering mob. Scenes such as this inspired Tennyson, very English and very conservative, to deprecate “the red fool fury of the Seine.” Ironically, the king’s failure to hold the revolution in check at an earlier stage was due to his refusal to have his troops fire on the people; he abhorred bloodshed.

Robespierre's death by Madame

Robespierre's death by Madame la Guillotine, July 28, 1794.

His death marked the end of the Reign of Terror.

A French engraving, circa 1799.

Ecclesia abhorret a sanguine (the Church abhors blood) was a tenet of the medieval Christian Church, but that didn’t keep the Inquisition from sentencing heretics to death. Granted, death by fire — by being burned at the stake — might not involve bloodshed, but the Church avoided the violence of executions by handing its victims over to the secular authorities, who nursed no such hypocritical reservations. And merry bonfires there were, and well attended, with the victims sometimes crying out, “More fuel, good people, more fuel!” in hopes of speeding up their death. If the wind was wrong and the fire burned slowly, what was usually a half-hour torment could stretch out to a full two hours.

Chained heretics burned at the stake.

Chained heretics burned at the stake. Date and source unknown.

Yes, bloodshed is abhorrent. The ultimate in horror is attained when a psychopathic killer drinks his victim’s blood. Yes, such acts have been recorded, and the offender isn’t a fictional creation like Dracula; he’s very real. (Yes, usually a man.). But these are individual psychopaths, not typical of society. And yet, in wartime one may wonder. Wartime films rarely survive into peacetime. I recall a film from World War II in which an Australian civilian showed his righteous rage and patriotism by choking a Japanese soldier to death. I can’t imagine it being shown in peacetime; it would be … yes, abhorrent.

But what if a whole society thinks that its survival depends on drinking human blood? Such was the Aztec belief. Only the sacrifice of human blood gave strength to the sun; without it, the sun would be overtaken and destroyed by the pursuing forces of darkness, causing the extinction of the human race. On prominent display in the National Anthropology Museum of Mexico City is the Aztec Calendar Stone, also known as the Aztec Sun Stone, a heavy circular stone close to 12 feet in diameter and 39 inches thick. When I saw it there many years ago, I was overwhelmed. Thinking that maybe, on this very stone, human sacrifices had once been performed, I felt both chilled and fascinated.. This may have been my overwrought imagination at work, but the stone is certainly linked to sacrifice. In its very center is a god holding a human heart in each of his clawlike hands, his protruding tongue in the shape of a sacrificial knife.

Rob Young

Rob YoungDepending on the state, in this country we allow the death penalty for certain crimes, but in modern times we don’t want blood to be shed. Too gross, too icky. So we shun the guillotine and try everything else: the electric chair, which sometimes has the victim twitching in agony; hanging, which sometimes leaves the victim likewise writhing in agony; and the gas chamber, a ”scientific” contraption that also lacks the quick finality of Madame Guillotine. No matter how you go at it to avoid the shedding of blood, it’s messy, and often downright cruel. I hadn’t anticipated ending on this note, but here indeed we are. Messy as they are, the guillotine and the stroke of an ax are mercifully quick and definitive.

Coming soon: Hot Mama: Goddess, Mother, Virgin, Whore. Not, in any conventional sense, a hymn to motherhood.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

Published on June 14, 2020 04:20

June 7, 2020

465. Americanisms

BROWDERBOOKS

For a lively three-star Reedsy Discovery review by Jennie Louwes of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, go here. (But it's too late to see her review as a video; that's over.)

As always, for my other books, go here.

SURVIVAL

The latest development in New York City survival: Stores are covering their front windows with panels of wood. I see this up and down Bleecker Street, where all the designer clothing stores are shut. Why the wood? In case rioters come by and start throwing rocks at windows. Riots have plagued the West Village also, though my Eleventh Street block has been quiet.

New York City police ready for rioters, June 3, 2020.

New York City police ready for rioters, June 3, 2020.

Janine and Jim Eden

The famous Magnolia Bakery is still open and without wood panels, and announces that it is baking to celebrate 2020 graduates, home, Mom, doctors, nurses, teachers, neighbors, prom, and just about everyone and everything else. Their gooey goodies are obviously necessary to our well-being and the economy.

Another unforeseen development: The city is so quiet, the streets almost empty, and the parks unvisited, that the birds are reclaiming habitat and serenading us with song. The peak of the spring migration is over, but this is the nesting season, when males sound off to attract a mate and claim turf, and they can be heard now better than when the city emits its usual rumble and roar. The red-winged blackbird, flaunting its bright red shoulder patches, is livening the cattails with its vibrant konk-la-reee.

Andy Reago and Chrissy McClarren

Andy Reago and Chrissy McClarren

The common yellowthroat, a warbler, is repeating witchety witchety witchety in clumps of shrubs and grasses; the wood thrush, its breast boldly spotted, is giving out its haunting three-note call in the brush of the Central Park Ramble; and the long-beaked willet is calling out its name -- will will willet, will will willet -- over the ponds in the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. These are all old friends of mine; hunting them, I often trekked these habitats. Welcome back, songsters, and may your music lift our spirits; we could use a lift.

AMERICANISMS

These are expressions that mark the speaker as an American, or as someone trying to speak like an American. Some were uttered by persons of note, and others just came into existence, who knows how or why. But they all say something not just about the speaker, but also about the speaker’s country, its mindset, its mores, the way it intentionally or unintentionally presents itself to the world.

By way of contrast, when I was in England long ago, I remember signs saying KEEP BRITAIN TIDY. I cannot imagine such a sign in this country. America is just too big, too diverse, and too feisty to aspire to tidiness. Cleanliness, maybe, but tidy never.

And the Brits want to keep their language tidy, too. They cringe at Americanisms like “gas” for “petrol,” and “pants” for “trousers,” as well as some of the items listed below. Their language, they complain, is being “colonised” or even “killed” by Americanisms, though some of the words they disparage are actually English, not American, in origin. And the “stiff upper lip” so associated with the English is in fact an Americanism. Language plays tricks on us all.

So here, in no particular order, is my list of Americanisms, with my personal comments thrown in. I invite readers to make some additional suggestions of their own.

I feel like a million dollars. A French-born friend of my mother’s used this and other expressions to show how she was completely at home in American English.

Make the world safe for democracy! A World War I slogan, but the impulse persists, with both desirable and disastrous consequences.

Liberty and union, now and forever, one and inseparable. Inscription on the base of a bigger-than-life statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park, expressing his views in the famous Webster-Hayne debate of 1830, when Webster, a senator from Massachusetts, debated Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina. Webster believed in a strong federal government, whereas Hayne upheld state’s rights, including the right to secede from the Union. Our Civil War (1861-1865), at a cost of over 618,000 lives, settled the issue, though Texas likes to forget this.

Simeon87

Simeon87

Lafayette, we are here. Attributed to General John J. Pershing, commander of the American forces sent to France in 1917, but actually spoken by a subordinate. Lafayette had helped us get our independence; now we would help his country in its war with Germany.

Pike’s Peak or bust. Sign on covered wagons heading west in the 1840s for Colorado and beyond.

I have seen the elephant. Sign on covered wagons coming back from the West in the 1840s, indicating disillusion with what they had found. Probably inspired by early circuses and road shows that displayed an elephant.

God’s country. That beautifully satisfying locale that you once saw and hope to return to, or that exists in your imagination. Implies a country where people travel a lot and get displaced. Also, a people who dream of better. Inevitably, a magnet for hope and heartbreak. Years ago when I was a graduate student at Columbia, I often had a beer (or two or three) at the West End bar on Broadway. There, entertaining us with his tales of “making out” — seducing every woman in sight — was an amusing young dude who found in the rest of us the audience that his ego and libido required. He was from somewhere in the West, and one night, referring to it, said quite seriousky, with a touch of nostalgia, “That’s God’s country.” His momentary seriousness astonished me, but he soon resumed his tale of penile successes.

There’s a sucker born every minute. Attributed to Phineas T. Barnum, the nineteenth-century showman and circus impresario, and prince of humbug. He displayed fake freaks and exotic animals to a seemingly naive public (“suckers”), some of whom knowingly went along for entertainment and the joke.

The business of America is business. A saying of Calvin Coolidge, U.S. president from 1924 to 1928. So dull, visionless, and reticent a man that he became legendary. But let’s face it, America is devoted to capitalism and the work ethic.

Keep your shirt on. Stay calm, don’t get angry or excited. Possible explanation: In the nineteenth century clothes were expensive, so many men owned only one or two shirts.

Beats me. I don’t know, I don’t understand. Origin unknown.

That gets my goat. To make someone annoyed or angry. Origin unknown.

It isn’t over until the fat lady sings. Don’t presume to know the outcome of an event still in progress. I always thought it came from vaudeville, but it’s a newbie and relates to -- of all people -- Richard Wagner. His interminably long but sporadically brilliant Ring cycle isn’t over until Brünnhilde, often sung by a buxom soprano, has sung her last note. Probably first used by U.S. sportscaster Ralph Carpenter in a 1976 interview, referring to a tight basketball game or season, though other explanations abound.

Fuhgeddaboudit. Brooklynese for “forget about it,” meaning it’s unlikely. Another newbie, attributed to the 1960s TV show “The Honeymooners,” set in Brooklyn. But I wonder if it didn’t originate much earlier.

Baloney! Nonsense, claptrap, bunk. Dates from 1922. Linked to the bologna, a large smoked meat sausage typically made from leftover scraps of meat.

He struck out, It’s the ninth inning, A curve ball, Touch base, A whole new ballgame, etc. From baseball, the most American of sports, and in my opinion, the dullest.

Normalcy. That’s where Warren G. Harding, U.S. president 1920-1923, wanted us to return, though it should be “normality.” Since Harding was another of our least brilliant presidents, and surrounded by crooks when in office, I avoid his creation and insist on “normality.”

Okay. Totally American, though now understood worldwide. Long ago, when a friend and I were bargaining for serapes in the open-air market of Oaxaca, Mexico, after a long haggle we failed to get our price and started to walk away. Faced with the loss of a sale of three serapes, the Mexican vendor, a shrewd little man whose gold fillings twinkled in the sun, rushed after us and said, “Okay.” There are many stories about the expression’s origins. Probably came from “orl korrect,” a humorous misspelling of “all correct,” circa 1840.

To go the whole hog. To go all the way, to do something. Possible origin: Butchers used to use every part of the animal. The skin was tanned for leather, and the hooves were pickled. To go the whole hog was to use every part of the animal.

To face the music. To accept the consequences of one’s actions. Possible origin: A disgraced military officer was “drummed out” of his regiment. Or: An actor going onstage faces the orchestra pit. Dates from the 1830s.

To keep one’s cool. To stay calm, not be upset or angry. This use of “cool” as a noun dates from the 1950s or earlier. It may be significant that in the 1940s Miles Davis called his music “cool jazz,” to differentiate it from the “hot jazz” that originated in New Orleans in the early 1900s and came North. (And if you want to start a passionate debate that has no end, just ask the origin and history of the word “jazz.” There are many answers, some of them deliciously naughty.)

Americanisms that are no longer (thank God) used:“Bone pit” for cemetery.“Tooth carpenter” for dentist.“To give someone the mitten” for “to throw someone [a boyfriend or suitor] over.”To which I'll add another: "gay deceiver" for "skirt chaser," a man who aggressively pursues women. Our current use of "gay" obviously complicates things. And as mentioned in Tennessee Williams's play The Glass Menagerie, "gay deceivers" once also meant padding that young women inserted in their bodice or bra to plump out their figure. A reminder that language is never static; it is constantly changing.

Coming soon: "Blood."

© 2020 Clifford Browder

For a lively three-star Reedsy Discovery review by Jennie Louwes of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, go here. (But it's too late to see her review as a video; that's over.)

As always, for my other books, go here.

SURVIVAL

The latest development in New York City survival: Stores are covering their front windows with panels of wood. I see this up and down Bleecker Street, where all the designer clothing stores are shut. Why the wood? In case rioters come by and start throwing rocks at windows. Riots have plagued the West Village also, though my Eleventh Street block has been quiet.

New York City police ready for rioters, June 3, 2020.

New York City police ready for rioters, June 3, 2020.Janine and Jim Eden

The famous Magnolia Bakery is still open and without wood panels, and announces that it is baking to celebrate 2020 graduates, home, Mom, doctors, nurses, teachers, neighbors, prom, and just about everyone and everything else. Their gooey goodies are obviously necessary to our well-being and the economy.

Another unforeseen development: The city is so quiet, the streets almost empty, and the parks unvisited, that the birds are reclaiming habitat and serenading us with song. The peak of the spring migration is over, but this is the nesting season, when males sound off to attract a mate and claim turf, and they can be heard now better than when the city emits its usual rumble and roar. The red-winged blackbird, flaunting its bright red shoulder patches, is livening the cattails with its vibrant konk-la-reee.

Andy Reago and Chrissy McClarren

Andy Reago and Chrissy McClarrenThe common yellowthroat, a warbler, is repeating witchety witchety witchety in clumps of shrubs and grasses; the wood thrush, its breast boldly spotted, is giving out its haunting three-note call in the brush of the Central Park Ramble; and the long-beaked willet is calling out its name -- will will willet, will will willet -- over the ponds in the Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge. These are all old friends of mine; hunting them, I often trekked these habitats. Welcome back, songsters, and may your music lift our spirits; we could use a lift.

AMERICANISMS

These are expressions that mark the speaker as an American, or as someone trying to speak like an American. Some were uttered by persons of note, and others just came into existence, who knows how or why. But they all say something not just about the speaker, but also about the speaker’s country, its mindset, its mores, the way it intentionally or unintentionally presents itself to the world.

By way of contrast, when I was in England long ago, I remember signs saying KEEP BRITAIN TIDY. I cannot imagine such a sign in this country. America is just too big, too diverse, and too feisty to aspire to tidiness. Cleanliness, maybe, but tidy never.

And the Brits want to keep their language tidy, too. They cringe at Americanisms like “gas” for “petrol,” and “pants” for “trousers,” as well as some of the items listed below. Their language, they complain, is being “colonised” or even “killed” by Americanisms, though some of the words they disparage are actually English, not American, in origin. And the “stiff upper lip” so associated with the English is in fact an Americanism. Language plays tricks on us all.

So here, in no particular order, is my list of Americanisms, with my personal comments thrown in. I invite readers to make some additional suggestions of their own.

I feel like a million dollars. A French-born friend of my mother’s used this and other expressions to show how she was completely at home in American English.

Make the world safe for democracy! A World War I slogan, but the impulse persists, with both desirable and disastrous consequences.

Liberty and union, now and forever, one and inseparable. Inscription on the base of a bigger-than-life statue of Daniel Webster in Central Park, expressing his views in the famous Webster-Hayne debate of 1830, when Webster, a senator from Massachusetts, debated Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina. Webster believed in a strong federal government, whereas Hayne upheld state’s rights, including the right to secede from the Union. Our Civil War (1861-1865), at a cost of over 618,000 lives, settled the issue, though Texas likes to forget this.

Simeon87

Simeon87Lafayette, we are here. Attributed to General John J. Pershing, commander of the American forces sent to France in 1917, but actually spoken by a subordinate. Lafayette had helped us get our independence; now we would help his country in its war with Germany.

Pike’s Peak or bust. Sign on covered wagons heading west in the 1840s for Colorado and beyond.

I have seen the elephant. Sign on covered wagons coming back from the West in the 1840s, indicating disillusion with what they had found. Probably inspired by early circuses and road shows that displayed an elephant.

God’s country. That beautifully satisfying locale that you once saw and hope to return to, or that exists in your imagination. Implies a country where people travel a lot and get displaced. Also, a people who dream of better. Inevitably, a magnet for hope and heartbreak. Years ago when I was a graduate student at Columbia, I often had a beer (or two or three) at the West End bar on Broadway. There, entertaining us with his tales of “making out” — seducing every woman in sight — was an amusing young dude who found in the rest of us the audience that his ego and libido required. He was from somewhere in the West, and one night, referring to it, said quite seriousky, with a touch of nostalgia, “That’s God’s country.” His momentary seriousness astonished me, but he soon resumed his tale of penile successes.

There’s a sucker born every minute. Attributed to Phineas T. Barnum, the nineteenth-century showman and circus impresario, and prince of humbug. He displayed fake freaks and exotic animals to a seemingly naive public (“suckers”), some of whom knowingly went along for entertainment and the joke.

The business of America is business. A saying of Calvin Coolidge, U.S. president from 1924 to 1928. So dull, visionless, and reticent a man that he became legendary. But let’s face it, America is devoted to capitalism and the work ethic.

Keep your shirt on. Stay calm, don’t get angry or excited. Possible explanation: In the nineteenth century clothes were expensive, so many men owned only one or two shirts.

Beats me. I don’t know, I don’t understand. Origin unknown.

That gets my goat. To make someone annoyed or angry. Origin unknown.

It isn’t over until the fat lady sings. Don’t presume to know the outcome of an event still in progress. I always thought it came from vaudeville, but it’s a newbie and relates to -- of all people -- Richard Wagner. His interminably long but sporadically brilliant Ring cycle isn’t over until Brünnhilde, often sung by a buxom soprano, has sung her last note. Probably first used by U.S. sportscaster Ralph Carpenter in a 1976 interview, referring to a tight basketball game or season, though other explanations abound.

Fuhgeddaboudit. Brooklynese for “forget about it,” meaning it’s unlikely. Another newbie, attributed to the 1960s TV show “The Honeymooners,” set in Brooklyn. But I wonder if it didn’t originate much earlier.

Baloney! Nonsense, claptrap, bunk. Dates from 1922. Linked to the bologna, a large smoked meat sausage typically made from leftover scraps of meat.

He struck out, It’s the ninth inning, A curve ball, Touch base, A whole new ballgame, etc. From baseball, the most American of sports, and in my opinion, the dullest.

Normalcy. That’s where Warren G. Harding, U.S. president 1920-1923, wanted us to return, though it should be “normality.” Since Harding was another of our least brilliant presidents, and surrounded by crooks when in office, I avoid his creation and insist on “normality.”

Okay. Totally American, though now understood worldwide. Long ago, when a friend and I were bargaining for serapes in the open-air market of Oaxaca, Mexico, after a long haggle we failed to get our price and started to walk away. Faced with the loss of a sale of three serapes, the Mexican vendor, a shrewd little man whose gold fillings twinkled in the sun, rushed after us and said, “Okay.” There are many stories about the expression’s origins. Probably came from “orl korrect,” a humorous misspelling of “all correct,” circa 1840.

To go the whole hog. To go all the way, to do something. Possible origin: Butchers used to use every part of the animal. The skin was tanned for leather, and the hooves were pickled. To go the whole hog was to use every part of the animal.

To face the music. To accept the consequences of one’s actions. Possible origin: A disgraced military officer was “drummed out” of his regiment. Or: An actor going onstage faces the orchestra pit. Dates from the 1830s.

To keep one’s cool. To stay calm, not be upset or angry. This use of “cool” as a noun dates from the 1950s or earlier. It may be significant that in the 1940s Miles Davis called his music “cool jazz,” to differentiate it from the “hot jazz” that originated in New Orleans in the early 1900s and came North. (And if you want to start a passionate debate that has no end, just ask the origin and history of the word “jazz.” There are many answers, some of them deliciously naughty.)

Americanisms that are no longer (thank God) used:“Bone pit” for cemetery.“Tooth carpenter” for dentist.“To give someone the mitten” for “to throw someone [a boyfriend or suitor] over.”To which I'll add another: "gay deceiver" for "skirt chaser," a man who aggressively pursues women. Our current use of "gay" obviously complicates things. And as mentioned in Tennessee Williams's play The Glass Menagerie, "gay deceivers" once also meant padding that young women inserted in their bodice or bra to plump out their figure. A reminder that language is never static; it is constantly changing.

Coming soon: "Blood."

© 2020 Clifford Browder

Published on June 07, 2020 04:00

May 31, 2020

464. Two stories and survival.

BROWDERBOOKS

For a lively three-star Reedsy Discovery video review by Jennie Louwes of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, go here. She loves New York and even briefly sings for you. This is new for me -- a video review.

As always, for my other books, go here.

And the eternally promised and eternally delayed website? It's still in the final final final stages of development, and frankly, a pain in the ass. Which has nothing to do with the final product, once it's finally final. But getting there ain't half the fun.

Two Stories

Mr. Frankfurter

Long ago a young woman told me two stories, both short. She worked as secretary for a man named Frankfurter. One day a serious letter came, addressed to Mr. Hamburger. I repeat: a serious letter, not a joke. Her boss was visibly annoyed. She thought it hilarious, as did I, when she told me.

Group Therapy

She also was doing group therapy: no therapist, just a bunch of people sharing worries and concerns. One of the men complained bitterly and repeatedly about his domineering mother. Finally one member of the group, exasperated, said to him, "Get rid of her." Then another said, "Yes, get rid of her." Then the whole group joined together in a chorus, saying repeatedly, "Get rid of her! Get rid of her! Get rid of her!" And right there, in front of all, he vomited.

Survival

It's what we're all doing now in New York, most of us masked and observing social distancing. My friends are stir-crazy. Three now have phoned me for a lengthy conversation, faute de mieux.

Every week or so I order food from LifeThyme, a health-food store on Sixth Avenue, through a service called Mercato. It's simple: you see online what the store has to offer, click on the desired items, pay by Paypal or a credit card, and select a delivery time, usually on the following day. Delivery fee and tip are included in the charge. I know from experience that not all my chosen items will be available, so I order more than I need. Though I ask them to phone me if some are unavailable, so we can arrange substitutions, often do not. But the food always comes, delivered up the four steep flights, and I am glad to get it. So for residents of New York, I highly recommend Mercato. And if you don't want a health-food store, lots of other stores are also available.

And laundry? My laundry is open on Tuesdays and Fridays, and it does do pick-up and delivery. When I had my laundry done a few days ago, they picked it up circa 10 a.m. and delivered it by mid-afternoon -- unbelievably fast! I suspect that they're not getting much business these days, which is surprising, to say the least.

Janine and Jim Eden

Janine and Jim Eden

One group of New Yorkers who are happy about the empty streets is motorcyclists, since they have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to speed down thoroughfares free of traffic and all the problems it can pose. Some of them enjoy it thoroughly, like one on the Westside Highway who praised the beauty of the Hudson River, with views ranging as far as the George Washington Bridge and the Palisades. Others admit that it's a guilty pleasure, given the suffering of so many, and also keep in mind that injuries from a motorcycle accident would not rank high in the minds of careworn hospital staff busy with the virus. And a few bikers are doing public service by bringing protective equipment, food, and other supplies to essential workers.

So it goes: masks, six-foot distancing, phone calls for company, food and laundry delivered, and motorcycles on empty streets. As I said once before, New Yorkers can survive anything, if they have four essentials: courage, faith, hope, and toilet paper. Especially toilet paper, as was obvious in the frenzied sales of it during the first panicky phase of the lockdown.

Inspired by the virus: a panic sign with toilet paper.

Inspired by the virus: a panic sign with toilet paper.

The RedBurn, Fry 1989.

One last note: The Abingdon Square greenmarket still appears on Saturday morning, and yesterday, in addition to my beloved olive bread, blueberry muffin, and cookies, I got two boxes of strawberries and a pound of fresh-picked Brussels sprouts. And in the park nearby, a rose bush was in full bloom, assaulting the eye with a blast of bright red blossoms. The virus can't stop nature.

Coming soon: Americanisms: expressions that mark the speaker as an American, or as someone trying to talk like us. And why they make the Brits wince and cringe.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

For a lively three-star Reedsy Discovery video review by Jennie Louwes of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, go here. She loves New York and even briefly sings for you. This is new for me -- a video review.

As always, for my other books, go here.

And the eternally promised and eternally delayed website? It's still in the final final final stages of development, and frankly, a pain in the ass. Which has nothing to do with the final product, once it's finally final. But getting there ain't half the fun.

Two Stories

Mr. Frankfurter

Long ago a young woman told me two stories, both short. She worked as secretary for a man named Frankfurter. One day a serious letter came, addressed to Mr. Hamburger. I repeat: a serious letter, not a joke. Her boss was visibly annoyed. She thought it hilarious, as did I, when she told me.

Group Therapy

She also was doing group therapy: no therapist, just a bunch of people sharing worries and concerns. One of the men complained bitterly and repeatedly about his domineering mother. Finally one member of the group, exasperated, said to him, "Get rid of her." Then another said, "Yes, get rid of her." Then the whole group joined together in a chorus, saying repeatedly, "Get rid of her! Get rid of her! Get rid of her!" And right there, in front of all, he vomited.

Survival

It's what we're all doing now in New York, most of us masked and observing social distancing. My friends are stir-crazy. Three now have phoned me for a lengthy conversation, faute de mieux.

Every week or so I order food from LifeThyme, a health-food store on Sixth Avenue, through a service called Mercato. It's simple: you see online what the store has to offer, click on the desired items, pay by Paypal or a credit card, and select a delivery time, usually on the following day. Delivery fee and tip are included in the charge. I know from experience that not all my chosen items will be available, so I order more than I need. Though I ask them to phone me if some are unavailable, so we can arrange substitutions, often do not. But the food always comes, delivered up the four steep flights, and I am glad to get it. So for residents of New York, I highly recommend Mercato. And if you don't want a health-food store, lots of other stores are also available.

And laundry? My laundry is open on Tuesdays and Fridays, and it does do pick-up and delivery. When I had my laundry done a few days ago, they picked it up circa 10 a.m. and delivered it by mid-afternoon -- unbelievably fast! I suspect that they're not getting much business these days, which is surprising, to say the least.

Janine and Jim Eden

Janine and Jim EdenOne group of New Yorkers who are happy about the empty streets is motorcyclists, since they have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to speed down thoroughfares free of traffic and all the problems it can pose. Some of them enjoy it thoroughly, like one on the Westside Highway who praised the beauty of the Hudson River, with views ranging as far as the George Washington Bridge and the Palisades. Others admit that it's a guilty pleasure, given the suffering of so many, and also keep in mind that injuries from a motorcycle accident would not rank high in the minds of careworn hospital staff busy with the virus. And a few bikers are doing public service by bringing protective equipment, food, and other supplies to essential workers.

So it goes: masks, six-foot distancing, phone calls for company, food and laundry delivered, and motorcycles on empty streets. As I said once before, New Yorkers can survive anything, if they have four essentials: courage, faith, hope, and toilet paper. Especially toilet paper, as was obvious in the frenzied sales of it during the first panicky phase of the lockdown.

Inspired by the virus: a panic sign with toilet paper.

Inspired by the virus: a panic sign with toilet paper.The RedBurn, Fry 1989.

One last note: The Abingdon Square greenmarket still appears on Saturday morning, and yesterday, in addition to my beloved olive bread, blueberry muffin, and cookies, I got two boxes of strawberries and a pound of fresh-picked Brussels sprouts. And in the park nearby, a rose bush was in full bloom, assaulting the eye with a blast of bright red blossoms. The virus can't stop nature.

Coming soon: Americanisms: expressions that mark the speaker as an American, or as someone trying to talk like us. And why they make the Brits wince and cringe.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

Published on May 31, 2020 03:50

May 22, 2020

463. Free? Kill it!

BROWDERBOOKS

My new nonfiction title, New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, is still featured on Reedsy Discovery. The first chapter is available there free, but the book has only four upvotes, needs more. You will earn the author's undying gratitude if you go there and give the book an upvote. You don't have to buy it or read the sample, just click on Upvote. You can buy it there, if you wish, or get the ebook or the print version from Amazon and Barnes & Noble. A good read for people homebound in lockdown. A tip: If you hurry, you may even get the ebook free -- yes, I said free -- from Amazon. Don't ask me why. There's some kind of credit available, though I don't know for how long.

My new website will be up and running soon. The virus slowed it down, but now it's almost finished.

FREE? KILL IT!

Common advice to authors without a large following: to get your new book known online, offer it free. So I did. I offered 100 ebook copies of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You in a Goodreads giveaway absolutely, totally, and joyously free. And what did I get? A batch of lousy reader reviews. Said one reader: “Don’t waste your time.” Said another: “Not my cup of tea, I am not the target audience.” Others were slightly kinder, and one actually praised it in a four-star review. But the initial overall tone was negative. Yet this very same book has received a string of positive editorial reviews, “editorial” meaning reviews from professional reviewers, as opposed to casual readers. So why the divergence? What gives?

I don’t mind negative reviews, if I can learn from them, and I learned a useful lesson from these. With a couple of exceptions, these reviews came from readers who had no special interest in New York and New Yorkers. So why did they even glance at my book? Because it was free. And why were the editorial reviews so positive? Because those reviewers had an interest in the subject matter that attracted them to the book. Lesson learned: Don’t offer free books, except to a targeted audience with an interest in the contents. Free is okay if offered to that audience, but risks rejection if offered to readers generally. My motto henceforth: Free? Kill it.

Helena Rubinstein

Helena Rubinstein

She practiced what she preached.

Even at age 40 or 50, her skin was without a wrinkle.

Offering something free actually depreciates its value. Savvy retailers, especially those selling fashion and luxury items, know this and exploit it to the hilt. Helena Rubinstein (1872-1965) built an international chain of beauty salons whose targeted audience was affluent women concerned with their appearance. Those women had money and were prepared to spend it, if it gave them what they wanted. And Helena Rubinstein, whose motto was “beauty is power,” offered them salons where the staff “diagnosed” the patrons’ skin problems and “prescribed” the appropriate treatment. This gave glamour a scientific look. Rubinstein was selling the illusion of youth and beauty, and the higher the price of her products and services, the more her customers valued them. The last thing they wanted was cheap, not to mention free.

A patron getting treated at Rubinstein's Fifth Avenue spa.

A patron getting treated at Rubinstein's Fifth Avenue spa.

“There are no ugly women,” Rubinstein insisted, “only lazy ones.” So beauty was available to all — well, not quite all — at a price. And in her seven-story flagship New York City spa, the center of her empire, she added a gym, a restaurant, sumptuous displays of modern art, and classrooms offering instruction in facial care. Eager for this very special experience that her spa promoted, and for the attention that would be given them by “experts,” women flocked to it and spent half the day there. So what if it cost a small fortune? It was worth it; they paid gladly and would soon come back for more.

(For more on Rubinstein, see chapter 15 of my nonfiction work, Fascinating New Yorkers: Power Freaks, Mobsters, Liberated Women, Creators, Queers and Crazies, available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Rubinstein was a bit of a power freak, certainly a liberated woman and a creator, but in no way crazy. Savvy to the crux of her being, she died a billionaire.)

Coming soon: ???

© 2020 Clifford Browder

My new nonfiction title, New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, is still featured on Reedsy Discovery. The first chapter is available there free, but the book has only four upvotes, needs more. You will earn the author's undying gratitude if you go there and give the book an upvote. You don't have to buy it or read the sample, just click on Upvote. You can buy it there, if you wish, or get the ebook or the print version from Amazon and Barnes & Noble. A good read for people homebound in lockdown. A tip: If you hurry, you may even get the ebook free -- yes, I said free -- from Amazon. Don't ask me why. There's some kind of credit available, though I don't know for how long.

My new website will be up and running soon. The virus slowed it down, but now it's almost finished.

FREE? KILL IT!

Common advice to authors without a large following: to get your new book known online, offer it free. So I did. I offered 100 ebook copies of New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You in a Goodreads giveaway absolutely, totally, and joyously free. And what did I get? A batch of lousy reader reviews. Said one reader: “Don’t waste your time.” Said another: “Not my cup of tea, I am not the target audience.” Others were slightly kinder, and one actually praised it in a four-star review. But the initial overall tone was negative. Yet this very same book has received a string of positive editorial reviews, “editorial” meaning reviews from professional reviewers, as opposed to casual readers. So why the divergence? What gives?

I don’t mind negative reviews, if I can learn from them, and I learned a useful lesson from these. With a couple of exceptions, these reviews came from readers who had no special interest in New York and New Yorkers. So why did they even glance at my book? Because it was free. And why were the editorial reviews so positive? Because those reviewers had an interest in the subject matter that attracted them to the book. Lesson learned: Don’t offer free books, except to a targeted audience with an interest in the contents. Free is okay if offered to that audience, but risks rejection if offered to readers generally. My motto henceforth: Free? Kill it.

Helena Rubinstein

Helena RubinsteinShe practiced what she preached.

Even at age 40 or 50, her skin was without a wrinkle.

Offering something free actually depreciates its value. Savvy retailers, especially those selling fashion and luxury items, know this and exploit it to the hilt. Helena Rubinstein (1872-1965) built an international chain of beauty salons whose targeted audience was affluent women concerned with their appearance. Those women had money and were prepared to spend it, if it gave them what they wanted. And Helena Rubinstein, whose motto was “beauty is power,” offered them salons where the staff “diagnosed” the patrons’ skin problems and “prescribed” the appropriate treatment. This gave glamour a scientific look. Rubinstein was selling the illusion of youth and beauty, and the higher the price of her products and services, the more her customers valued them. The last thing they wanted was cheap, not to mention free.

A patron getting treated at Rubinstein's Fifth Avenue spa.

A patron getting treated at Rubinstein's Fifth Avenue spa.“There are no ugly women,” Rubinstein insisted, “only lazy ones.” So beauty was available to all — well, not quite all — at a price. And in her seven-story flagship New York City spa, the center of her empire, she added a gym, a restaurant, sumptuous displays of modern art, and classrooms offering instruction in facial care. Eager for this very special experience that her spa promoted, and for the attention that would be given them by “experts,” women flocked to it and spent half the day there. So what if it cost a small fortune? It was worth it; they paid gladly and would soon come back for more.

(For more on Rubinstein, see chapter 15 of my nonfiction work, Fascinating New Yorkers: Power Freaks, Mobsters, Liberated Women, Creators, Queers and Crazies, available from Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Rubinstein was a bit of a power freak, certainly a liberated woman and a creator, but in no way crazy. Savvy to the crux of her being, she died a billionaire.)

Coming soon: ???

© 2020 Clifford Browder

Published on May 22, 2020 14:51

May 19, 2020

462. Publisher, Survival, Website, Reedsy

BROWDERBOOKS

PUBLISHER

As some of you know already, I have signed a contract with E.L. Marker, an imprint of WiDo Publishing, to publish Forbidden Brownstones, the fifth title in my Metropolis series of novels set in nineteenth-century New York. This is a hybrid arrangement whereby the author retains full control, like in self-publishing, but gets assistance from an established press in producing and marketing the book. More of this as work on the book proceeds.

SURVIVAL, WEBSITE, REEDSY

Survival: I am fine. I go out rarely, mostly to get money from the bank, and food from the supermarket. I can get food delivered by a health food store, and often do. The Saturday morning greenmarket in Abingdon Square Park still functions, but with social distancing. My bread stand marks spots at six-foot intervals for its customers to line up, masked; last Saturday the line was so long that I found myself almost in Jersey. The streets now are strangely quiet; traffic is rare. I miss my weekly Sunday lunch out in a restaurant, and I miss seeing my friends, but it can't be helped. I wish everyone well in this trying time. We New Yorkers -- in fact, we Americans -- are a tough bunch. As demonstrated recently, to get us through a crisis, we need just four things:Courage.Patience.Faith.Toilet paper.With these, we can overcome all threats. But when will this end? Governor Cuomo is relaxing the lockdown upstate, but congested New York will be the last to return to normal, if it ever does. My planned book release party? Maybe in late September or early October ... maybe. At this point, who can be sure of anything?

Website: I've seen the latest proof, and it is exciting! It really says New York. Hopefully, the website will be functioning soon. Once it is, I'll announce it to all and sundry.

Reedsy: My new nonfiction title, New Yorkers: A Feisty People Who Will Unsettle, Madden, Amuse and Astonish You, is now live on Reedsy Discovery, where the first chapter is offered as a sample. Do go there and give me an Upvote. Lots of Upvotes will get the book more exposure.

Coming soon: Who knows? Maybe something on free, and why I won't ever do it again.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

Published on May 19, 2020 07:50

April 26, 2020

461. Dumb: Who Is and Who Isn't

BROWDERBOOKS

The good news: A good review of New Yorkers by the highly rated Midwest Book Review, which recommends it unreservedly "for community and academic library Contemporary American Biography collections," and the ebook for personal reading.

The bad news: The only Amazon reader review of the ebook is bad, and Amazon gives this much more attention than the good editorial reviews by professionals. I don't argue with the reviewer, who has every right to express his views. But I hate to have this the only review of the ebook. So HELP! Puleez give me a review, so this one bad review won't dominate. Remember:

Your review doesn't have to be long.You don't have to have read the whole book. Three or four chapters is enough.It doesn't have to be a rave (five stars). Be honest in your statement.To do a reader review, you have to have bought the book from Amazon. The cost of the ebook now is $5.99, but if you bought it earlier at $1.99, so much the better; I don't want to strain your budget. And the first one to do a review may actually get it free, since there's a credit available. (Don't ask me why.) If this first bad review is sandwiched in among four or five other less negative reviews, it will be neutralized. So puleez, go here and scroll down to the customer reviews.

And now, on to Dumb.

Dumb: Who Is and Who Isn't

Long ago, soon after the end of World War II, while visiting the family of my friend Martin in Speyer, West Germany (as it then was), I met his younger brother Hans. When I asked Hans what he liked to do, Hans without hesitation gave his answer in a single word: “Diskutieren” (to discuss, debate, argue). He said this with a look so acute, so charged with meaning, that I have never forgotten it. Hans, I sensed at once, would be a powerful opponent in a debate: fierce, ruthless, uncompromising. I didn’t want to argue with him, least of all politics, but the subject did come up. Of President Roosevelt’s trusting Stalin, our ally against Germany in World War II, Hans said that an American president should have more brains than a three-year-old child. “Das war nicht so einfach” (That wasn’t so simple) I managed to say in my faulty German, which was too limited to express my thought fully. What I wanted to say was this: Roosevelt trusted Stalin. Dumm! Stalin trusted Hitler. Dumm! Hitler attacked Russia. Dumm! All leaders, even (or maybe especially) the greatest, do dumb things. Remembering this recently, I started thinking about the dumb things we all do, and one thought led to another, and hence my subject: Dumb.

Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill in Teheran, 1943.

Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill in Teheran, 1943.

So who was smart, and who was dumb?

Let’s start at he top, the leaders I just mentioned. Roosevelt was as shrewd and savvy a president as we have ever had, and yes, during the war, he trusted Stalin. Stalin was our ally against Hitler, and without the Russians we could not have won the war. Churchill said that, to beat Hitler, he would have allied himself with the Devil, and perhaps he did. By 1945, the last year of the war, Roosevelt was a sick man, and he died on April 12 of that year. His leadership during the war had been brilliant, but in trusting Stalin to the extent he did, he may have been a bit, yes, dumb.

Stalin, in trusting Hitler, was dumber still. He had signed a nonagression pact with Hitler in August 1939, which gave Hitler a free hand to attack France in the spring of 1940. The resulting French collapse gave Hitler the mastery of continental Europe, minus Russia; Britain stood alone. So what did Stalin do? He didn’t just trust Hitler, he helped him in the war. The Germans wanted to send a warship, a raider, into the Pacific without encountering the British blockade. So Stalin agreed to help the raider fight its way through the frozen ice off the northern coast of European Russia and Siberia, and thus reach the Bering Sea and the Pacific without encountering any British ships. And the name of the ice-breaker that created a passageway for the raider? The Stalin.

But what was this, by way of dumb, compared to Stalin’s refusal to believe that Hitler was about to attack the Soviet Union in 1941? A German deserter crossed the border to warn the Russians, but Stalin didn’t believe his story and may even have had the man executed. One day later, the Germans attacked, with disastrous results for the Russians. Yes, in this instance Stalin was dumber, far dumber, than Roosevelt.

And Hitler’s attacking Russia was just as dumb. He had always planned to push to the east to acquire Lebensraum, but never appreciated the vastness of Russia, and the Russian ability to resist. When winter came and his troops bogged down short of Moscow, they didn’t even have winter uniforms, which were rushed to them belatedly. Dumber, perhaps, than Stalin. Once the French surrendered, Hitler admired Napoleon enough to visit his tomb in Paris, but he had never read the grim accounts of Napoleon’s little misadventure in Russia in 1812. Dumb, dumb, dumb.

Hitler and Mussolini, 1937. They both ended badly, both

Hitler and Mussolini, 1937. They both ended badly, both

were often dumb, but both had their brilliant moments, too.

And history gives us plenty examples of collective dumb. The Crusades are a good one, but I'll mention instead the medieval English and French attitude toward archery. In England, every village had archery contests, and all the men took pride in their skill, wanting to be the local Robin Hood. In France, meanwhile, there was a tax on bowstrings. So at the battle of Agincourt in 1415, where French knights in heavy armor slogged through thick mud against lightly armed English bowmen, who do you think won?

But haven't some world leaders been, not dumb, but brilliant? Of course.Roosevelt, who saved us psychologically from the Depression, and saw us through World War II. Bismarck, who tricked the French into declaring war in 1870, when he was prepared for war, and they were not. (Smart, the opposite of dumb, needn’t imply ethical.)Ben Franklin, a shrewd actor who, as our emissary to the court of Versailles, could also be charming, as witnessed by his friendships (were they only friendships?) with a number of titled ladies. Elizabeth I of England, who teased the princes and monarchs of Europe with the possibility of marrying her, playing one against another, when she had no intention of sacrificing her useful virginity. And who do I proclaim the dumbest, the absolutely dumbest, of world leaders? I'll mention just two and a half.

Kaiser Wilhelm. Lots of medals, though he

Kaiser Wilhelm. Lots of medals, though he

himself never saw battle as a soldier.

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany tops the list. A foolish saber-rattler, and so full of himself as to appear (to my American eyes) utterly ridiculous. The Archduke Francis Ferdinand, whose assassination in 1914 precipitated World War I. He went with his wife in an open car to Bosnia, a region known to be full of Serb nationalists eager to destroy the Austrian empire and create an all-Slav state. And he, as heir to the Austrian throne, was their ideal target. So if taking that little jaunt, its route announced in advance, wasn’t dumb, what is?And now the half: the Roman emperor Nero, said to have fiddled while Rome burned. Or is that just a story? If he did, maybe a little music wasn’t out of place, if there was nothing he could do to save the city. It may have calmed his nerves. So he counts as only a half.By way of dumb, none of our presidents comes to mind. “Stupid and inept” characterizes many of them, but that doesn’t make them dumb.

Enough of this discussion of dumb at the highest levels. By sticking to the past, I’ve tried to avoid contentious arguments about who, among the world’s leaders today, are dumb. I’ll leave that to my readers, and have no doubt that they bristle with opinions. But let’s, for a moment, get personal. Have we ourselves, good little citizens that we are, and not among the world’s prime movers, ever done anything dumb?

You bet! In my teen years I did a host of things that were just plain dumb, but I dismiss these adolescent follies, and everyone else’s as well, for they were inevitable, and part of growing up. Let’s focus on the dumb of maturity, much less excusable.Just out of college and hoping to snag a Fulbright scholarship to France, I went home for a year: a disastrous choice, since I had little social life, sank into depression, and flirted with suicide. Getting the Fulbright saved me. Yet if I hadn’t had that one year off, I wouldn’t have taken a first-year course in classical Greek, a choice I have never regretted. As Socrates used to say, γνῶθι σεαυτόν. (Puzzled? See below.)When I started writing fiction, I turned out autobiographical novels that were, to put it mildly, awful; the very thought of them makes me blush. In school from an early age I had loved classes in English and history. Why did it take me so long to realize that well-researched historical novels were just the thing for me? Dumb.I used to write my mother letters about my doings, and from the time of my Alaskan adventures on (I worked one summer there in a kitchen), she saved them. After she died, I got hold of them and destroyed them. Since I had given her only the surface of my life, they contained nothing to embarrass me. So why did I do it? Maybe a perverse joy in a kind of self-destruction, or a bitter urge to leave no trace of myself on earth. Today, as I write a memoir for a gay history archive to be made available to the public only ten years after my death, those letters would be invaluable. The surfaces alone of my life would tell me a lot that I’ve forgotten. But I destroyed those letters. Dumb. Really dumb.Today, with everyone going around masked, I, age 91, have yet to do it. Dumb? Maybe. But I go out rarely, observe social distancing, and wash my hands upon returning from errands. And I have finally ordered some masks. Maybe only half dumb, like Nero. And probably having less musical ability than he had, I can't even fiddle.

dave souza

dave souza

Enough of my dumb doings. How about you? Have you ever done things that were just plain flat out dumb? And do you have the courage to reveal them? Let me know. I’d love to mention them in this blog, but I promise not to do so with your name attached. So tell me. How have you been dumb?

One last candidate for dumb: my computer, and maybe all computers. When I mistype a word, mine doesn’t just signal an error, it inserts what it thinks I was trying to say. So when I look again at the screen, I see words I never dreamed of typing, and sometimes they express the very opposite of what I meant. If I mistype "please," I get "police." If I mistype "smart," I get "smattered." For sheer dumbness, computers beat humans every time. On this happy note I conclude.

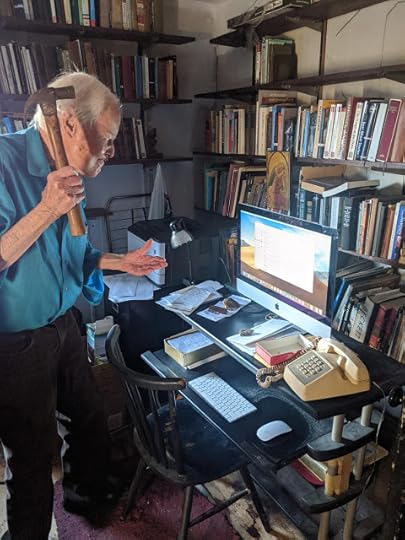

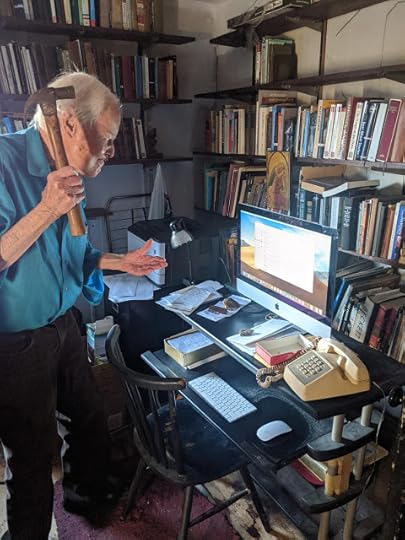

Me and my computer. Dumb, dumb, dumb.

Me and my computer. Dumb, dumb, dumb.

The computer, not me. But maybe both.

Photo credit: S. Berkowitz

Socrates’ advice to us all: γνῶθι σεαυτόν = “know thyself.” Which is far from dumb.

Coming soon: Maybe something, maybe nothing. It's not a good time.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

The good news: A good review of New Yorkers by the highly rated Midwest Book Review, which recommends it unreservedly "for community and academic library Contemporary American Biography collections," and the ebook for personal reading.

The bad news: The only Amazon reader review of the ebook is bad, and Amazon gives this much more attention than the good editorial reviews by professionals. I don't argue with the reviewer, who has every right to express his views. But I hate to have this the only review of the ebook. So HELP! Puleez give me a review, so this one bad review won't dominate. Remember:

Your review doesn't have to be long.You don't have to have read the whole book. Three or four chapters is enough.It doesn't have to be a rave (five stars). Be honest in your statement.To do a reader review, you have to have bought the book from Amazon. The cost of the ebook now is $5.99, but if you bought it earlier at $1.99, so much the better; I don't want to strain your budget. And the first one to do a review may actually get it free, since there's a credit available. (Don't ask me why.) If this first bad review is sandwiched in among four or five other less negative reviews, it will be neutralized. So puleez, go here and scroll down to the customer reviews.

And now, on to Dumb.

Dumb: Who Is and Who Isn't

Long ago, soon after the end of World War II, while visiting the family of my friend Martin in Speyer, West Germany (as it then was), I met his younger brother Hans. When I asked Hans what he liked to do, Hans without hesitation gave his answer in a single word: “Diskutieren” (to discuss, debate, argue). He said this with a look so acute, so charged with meaning, that I have never forgotten it. Hans, I sensed at once, would be a powerful opponent in a debate: fierce, ruthless, uncompromising. I didn’t want to argue with him, least of all politics, but the subject did come up. Of President Roosevelt’s trusting Stalin, our ally against Germany in World War II, Hans said that an American president should have more brains than a three-year-old child. “Das war nicht so einfach” (That wasn’t so simple) I managed to say in my faulty German, which was too limited to express my thought fully. What I wanted to say was this: Roosevelt trusted Stalin. Dumm! Stalin trusted Hitler. Dumm! Hitler attacked Russia. Dumm! All leaders, even (or maybe especially) the greatest, do dumb things. Remembering this recently, I started thinking about the dumb things we all do, and one thought led to another, and hence my subject: Dumb.

Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill in Teheran, 1943.

Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill in Teheran, 1943. So who was smart, and who was dumb?

Let’s start at he top, the leaders I just mentioned. Roosevelt was as shrewd and savvy a president as we have ever had, and yes, during the war, he trusted Stalin. Stalin was our ally against Hitler, and without the Russians we could not have won the war. Churchill said that, to beat Hitler, he would have allied himself with the Devil, and perhaps he did. By 1945, the last year of the war, Roosevelt was a sick man, and he died on April 12 of that year. His leadership during the war had been brilliant, but in trusting Stalin to the extent he did, he may have been a bit, yes, dumb.

Stalin, in trusting Hitler, was dumber still. He had signed a nonagression pact with Hitler in August 1939, which gave Hitler a free hand to attack France in the spring of 1940. The resulting French collapse gave Hitler the mastery of continental Europe, minus Russia; Britain stood alone. So what did Stalin do? He didn’t just trust Hitler, he helped him in the war. The Germans wanted to send a warship, a raider, into the Pacific without encountering the British blockade. So Stalin agreed to help the raider fight its way through the frozen ice off the northern coast of European Russia and Siberia, and thus reach the Bering Sea and the Pacific without encountering any British ships. And the name of the ice-breaker that created a passageway for the raider? The Stalin.

But what was this, by way of dumb, compared to Stalin’s refusal to believe that Hitler was about to attack the Soviet Union in 1941? A German deserter crossed the border to warn the Russians, but Stalin didn’t believe his story and may even have had the man executed. One day later, the Germans attacked, with disastrous results for the Russians. Yes, in this instance Stalin was dumber, far dumber, than Roosevelt.

And Hitler’s attacking Russia was just as dumb. He had always planned to push to the east to acquire Lebensraum, but never appreciated the vastness of Russia, and the Russian ability to resist. When winter came and his troops bogged down short of Moscow, they didn’t even have winter uniforms, which were rushed to them belatedly. Dumber, perhaps, than Stalin. Once the French surrendered, Hitler admired Napoleon enough to visit his tomb in Paris, but he had never read the grim accounts of Napoleon’s little misadventure in Russia in 1812. Dumb, dumb, dumb.

Hitler and Mussolini, 1937. They both ended badly, both

Hitler and Mussolini, 1937. They both ended badly, both were often dumb, but both had their brilliant moments, too.

And history gives us plenty examples of collective dumb. The Crusades are a good one, but I'll mention instead the medieval English and French attitude toward archery. In England, every village had archery contests, and all the men took pride in their skill, wanting to be the local Robin Hood. In France, meanwhile, there was a tax on bowstrings. So at the battle of Agincourt in 1415, where French knights in heavy armor slogged through thick mud against lightly armed English bowmen, who do you think won?

But haven't some world leaders been, not dumb, but brilliant? Of course.Roosevelt, who saved us psychologically from the Depression, and saw us through World War II. Bismarck, who tricked the French into declaring war in 1870, when he was prepared for war, and they were not. (Smart, the opposite of dumb, needn’t imply ethical.)Ben Franklin, a shrewd actor who, as our emissary to the court of Versailles, could also be charming, as witnessed by his friendships (were they only friendships?) with a number of titled ladies. Elizabeth I of England, who teased the princes and monarchs of Europe with the possibility of marrying her, playing one against another, when she had no intention of sacrificing her useful virginity. And who do I proclaim the dumbest, the absolutely dumbest, of world leaders? I'll mention just two and a half.

Kaiser Wilhelm. Lots of medals, though he

Kaiser Wilhelm. Lots of medals, though hehimself never saw battle as a soldier.

Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany tops the list. A foolish saber-rattler, and so full of himself as to appear (to my American eyes) utterly ridiculous. The Archduke Francis Ferdinand, whose assassination in 1914 precipitated World War I. He went with his wife in an open car to Bosnia, a region known to be full of Serb nationalists eager to destroy the Austrian empire and create an all-Slav state. And he, as heir to the Austrian throne, was their ideal target. So if taking that little jaunt, its route announced in advance, wasn’t dumb, what is?And now the half: the Roman emperor Nero, said to have fiddled while Rome burned. Or is that just a story? If he did, maybe a little music wasn’t out of place, if there was nothing he could do to save the city. It may have calmed his nerves. So he counts as only a half.By way of dumb, none of our presidents comes to mind. “Stupid and inept” characterizes many of them, but that doesn’t make them dumb.

Enough of this discussion of dumb at the highest levels. By sticking to the past, I’ve tried to avoid contentious arguments about who, among the world’s leaders today, are dumb. I’ll leave that to my readers, and have no doubt that they bristle with opinions. But let’s, for a moment, get personal. Have we ourselves, good little citizens that we are, and not among the world’s prime movers, ever done anything dumb?

You bet! In my teen years I did a host of things that were just plain dumb, but I dismiss these adolescent follies, and everyone else’s as well, for they were inevitable, and part of growing up. Let’s focus on the dumb of maturity, much less excusable.Just out of college and hoping to snag a Fulbright scholarship to France, I went home for a year: a disastrous choice, since I had little social life, sank into depression, and flirted with suicide. Getting the Fulbright saved me. Yet if I hadn’t had that one year off, I wouldn’t have taken a first-year course in classical Greek, a choice I have never regretted. As Socrates used to say, γνῶθι σεαυτόν. (Puzzled? See below.)When I started writing fiction, I turned out autobiographical novels that were, to put it mildly, awful; the very thought of them makes me blush. In school from an early age I had loved classes in English and history. Why did it take me so long to realize that well-researched historical novels were just the thing for me? Dumb.I used to write my mother letters about my doings, and from the time of my Alaskan adventures on (I worked one summer there in a kitchen), she saved them. After she died, I got hold of them and destroyed them. Since I had given her only the surface of my life, they contained nothing to embarrass me. So why did I do it? Maybe a perverse joy in a kind of self-destruction, or a bitter urge to leave no trace of myself on earth. Today, as I write a memoir for a gay history archive to be made available to the public only ten years after my death, those letters would be invaluable. The surfaces alone of my life would tell me a lot that I’ve forgotten. But I destroyed those letters. Dumb. Really dumb.Today, with everyone going around masked, I, age 91, have yet to do it. Dumb? Maybe. But I go out rarely, observe social distancing, and wash my hands upon returning from errands. And I have finally ordered some masks. Maybe only half dumb, like Nero. And probably having less musical ability than he had, I can't even fiddle.

dave souza

dave souzaEnough of my dumb doings. How about you? Have you ever done things that were just plain flat out dumb? And do you have the courage to reveal them? Let me know. I’d love to mention them in this blog, but I promise not to do so with your name attached. So tell me. How have you been dumb?

One last candidate for dumb: my computer, and maybe all computers. When I mistype a word, mine doesn’t just signal an error, it inserts what it thinks I was trying to say. So when I look again at the screen, I see words I never dreamed of typing, and sometimes they express the very opposite of what I meant. If I mistype "please," I get "police." If I mistype "smart," I get "smattered." For sheer dumbness, computers beat humans every time. On this happy note I conclude.

Me and my computer. Dumb, dumb, dumb.

Me and my computer. Dumb, dumb, dumb. The computer, not me. But maybe both.

Photo credit: S. Berkowitz

Socrates’ advice to us all: γνῶθι σεαυτόν = “know thyself.” Which is far from dumb.

Coming soon: Maybe something, maybe nothing. It's not a good time.

© 2020 Clifford Browder

Published on April 26, 2020 05:51

April 19, 2020

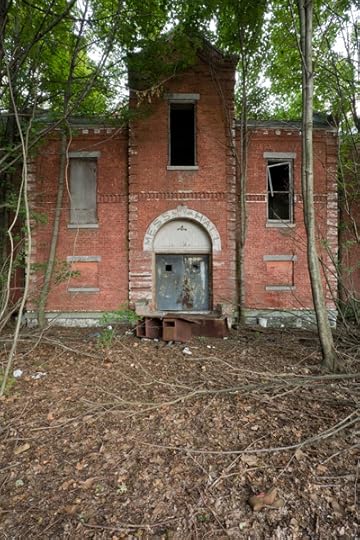

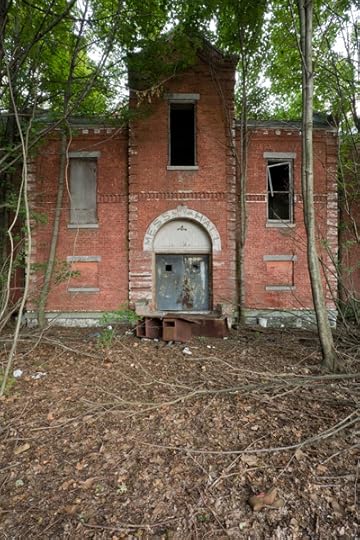

460. Getting Rid of the Unwanted Dead

BROWDERBOOKS