Kevin Power's Blog, page 11

April 9, 2018

New Short Story in Banshee

A new short story of mine appears in Issue 6 of Banshee, a wonderful literary journal edited by three young Irish writers, Eimear Ryan, Claire Hennessy, and Laura Cassidy. My story is called “A Theft” and it is, as the editors perceptively note, about “consent in various forms.” Fun fact: the title is itself stolen, from Saul Bellow. Quite aside from the calibre of the work that appears in it, Banshee is a physically beautiful object – wonderfully designed & a pleasure to read. Issue 6 is available now from good bookshops in Ireland & from Banshee’s website. Go forth, and purchase!

April 8, 2018

On That Simpsons Blog Post [UPDATED]

Since I posted it back in February, this piece on the decline of The Simpsons & the show’s hatred of Lisa has been attracting a fair amount of attention & commentary. In fact, as of today, it’s been viewed over 135,000 times, a datum that causes me to think to myself: There it is, Kev. The most popular thing you’ll ever write, and nobody paid you a cent for it. But – as Tony Soprano might say – whaddaya gonna do?

A sincere thank you to everyone who shared the piece and to everyone who took the time to comment on it. I’m thrilled and delighted that a piece I wrote mostly by accident (I didn’t really mean to watch all 629 episodes of The Simpsons in a month; it just sort of happened) has struck such a chord.

I should say at the outset that I think the piece’s popularity has much less to do with anything I contributed and much more to do with the fact that The Simpsons means so much to such a huge cohort of people. Anyone born in the 1980s or 1990s, after all, has pretty much absorbed The Simpsons the way 18th century aristocrats used to absorb the Roman poets. We speak Simpsons, we 80s and 90s kids. We use Simpsons quotes and allusions all the time – to make a point, to solidify a friendship, to make each other laugh. Often, we do this without even pausing to think about the specific derivation of what we’re saying. Case in point: my wife arrived home from work the other day, and as she was taking off her coat I said, “We found this one swimming naked in the Fermentarium.” “I AM THE LIZARD QUEEN!” she replied at once. This was what we said instead of, “Hi, how was your day?” I’d be willing to bet that there’s a million other couples out there who do the same thing. So The Simpsons is deeply important to us. I didn’t set out to find fault with the show; I watched the whole thing because I love it (and I still love it, in spite of everything). All I did was turn around and look at something that had been a part of my life for as long as I could remember, and try to see it afresh. I’m amazed that so many of you found value in my doing that. So again, thank you.

I’m going to try to address a few of the points that have been made about the post in the comments and on social media. (If you commented on the post and your comment never appeared, this is because you are a troll, and while you may be a wonderful and empathetic person in your day-to-day life, your online behaviour lacks both wonderfulness and empathy, & I have responded accordingly.) Here, in no particular order, are a few of the major points that have come up.

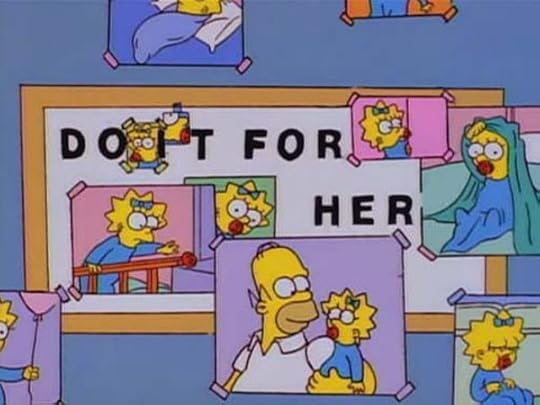

You say that Golden Age Simpsons wasn’t really about character. I couldn’t disagree more. What about Mr. Bergstrom? What about “Do It For Her”?

I should probably have clarified this point. For its first three seasons or so, The Simpsons was actually a pretty standard, warmhearted American sitcom, in which we’re meant to like the characters and be moved by their fairly trivial sufferings. And the show never fully abandoned this strain of warmhearted, mainstream sitcommery – in fact, it returned to it, in a weird, heartless, going-through-the-motions way, in its post-Golden Age period. But I would submit that if The Simpsons had never evolved past this stage in its development – if it had never become the surreal, absurdist comedy it became during its true Golden Age (let’s say from Season 5 to Season 10) – then I think it would never have become the show that we know and cherish, and we would not be having this conversation right now. At its purest – in “Itchy and Scratchy Land,” or in “Bart Vs. Australia,” or in “Homer Vs. the Eighteenth Amendment”, to take the first three examples that come to mind – The Simpsons moved way beyond standard sitcom character arcs and “Awwww!” moments and started doing something far more nihilistic and preposterous. If you love The Simpsons, I would humbly suggest, it is these episodes that you love. That’s My Two Cents, anyway.

Charlie Brown Never Kicks the Football

A lot of people have raised the point that Peanuts embodies a similar dynamic of aspiration and disappointment to the one I discovered in The Simpsons, and that this dynamic is often at the heart of successful comedy. I’m afraid I can’t really say much specifically about Charlie Brown et. al.: I grew up in Ireland, where Peanuts isn’t really a thing. But I do grant that a dream-crushing dynamic is often at the heart of good comedy. However, I think that The Simpsons, taken as a 629-episode aggregate, starts to go beyond this standard comedic strategy into more sinister, even pathological territory. Lisa’s punishments are often not really funny at all, as when every cat she tries to love is killed, or when she’s genuinely heartbroken about not being able to attend Cloisters Academy, or when – in “Boy Meets Curl” (Season 21 Episode 12) – she becomes addicted to collecting Winter Olympics pins and suffers meaninglessly as a result. In fact, these examples indicate exactly what I mean: it isn’t funny that Lisa keeps experiencing grief and loss in “I, (Annoyed Grunt)-bot,” and it isn’t funny that she doesn’t get to go to the school she desperately needs to go to in “Lisa Simpson, This Isn’t Your Life,” and it isn’t funny that Lisa sells her dress to buy more Olympics pins and winds up weeping on the street. Lisa’s grieving face, at the end of “Lisa Simpson, This Isn’t Your Life,” isn’t a punchline; it’s meant to move us. But it doesn’t move us in the “Awwww!” sort of way – i.e. the way it’s supposed to. Instead, it makes us uncomfortable, because we’re watching a genuinely warm & hopeful character having her dream deferred for the hundredth time.

Stretched out over 29 years, Lisa’s suffering accrues a weird sort of extra-textual gravity that doesn’t really have anything to do with what the writers of the show might have consciously intended. Once or twice it might be funny to see a warmhearted character rejected when she tries to make a friend; if you show this happening two dozen times or more, over three decades of episodes, it starts to say something troubling about how you see that character, and about the society you live in. This is why I used the words “punish” and “cruel” about the show’s treatment of Lisa. Her suffering is so repetitive, and so meaningless, that after a while it stops making an overtly satirical point about the frustrations of being an intellectual in our society and starts making an unconsciously grim point about how we as a society treat intellectuals, women, and women intellectuals.

The Simpsons is a Satire. It Exposes the World As it Really Is; Lisa’s Suffering Makes a Satirical Point about the Society We Live In.

Actually I think The Simpsons is only incidentally a satire. This is why I described it as an absurdist comedy in my original post. Individual episodes of The Simpsons are inarguably satirical – the key example might be “Homer Badman,” which satirises PC hysteria about sexual harassment and media overreaction to trivial news stories. And even in the post-Golden age period, individual jokes are unquestionably satirical (“You make a very adulterous point, Senator”). But generally speaking, The Simpsons – especially during the Golden Age – wasn’t really a satirical show. Satire typically exposes moral and intellectual faults to ridicule by exaggerating them to ludicrous extremes. It is generally more interested in making a programmatic moral point than it is in making you laugh. South Park is a satire – Trey Parker and Matt Stone have a set of clear political and moral values that enables them to discern what is wrong with certain trends and ideas. The Simpsons, which has cycled through many writers and many showrunners, has never had a coherent political and moral stance from which to satirise American culture. It seems to be broadly liberal – it dislikes Fox News, and so on. But to the extent that The Simpsons does have an implicit set of moral values, it is actually highly conservative: family is the most important thing; educated cosmopolitan types can’t be trusted; God punishes hubris; bullies are a part of the natural order; the stupid majority is always right; etc etc. To take one example: in “She of Little Faith” (Season 13 Episode 6), Lisa rejects Christianity. The rest of the family – and the rest of the town – are appalled, and try, rather cruelly, to manipulate Lisa into rejoining the church. Here is an opportunity for the show to suggest that people can live meaningful lives without religion – or, at the very least, to suggest that tolerance is preferable to unthinking zealotry. But instead, the show insists Lisa must have some kind of religion, so she becomes a Buddhist. The Simpsons can’t really imagine a life genuinely free of religious belief – because it thinks the majority is always right. Again and again, Marge’s narrow-minded, ill-informed, kneejerk religiosity is held up as the show’s idea of the proper path in life. Lisa’s independence must be carefully coralled. If The Simpsons owned up to this particular view of things, then it might qualify as a satire. But since it doesn’t, it remains a comedy that fails to acknowledge or understand its own reactionary assumptions. Or so I would suggest.

Shut Up, Meg

I’ve read a fair number of comments suggesting that Family Guy‘s treatment of Meg echoes The Simpsons‘ treatment of Lisa. I think to conflate the two is something of a category error. Family Guy works by invoking racist, homophobic, misogynist, and anti-Semitic jokes in a frame of cheap irony, allowing it (on the one hand) to make crass and offensive jokes about women, minorities, Jews, and queer people, and (on the other) to frame those jokes as ironic parodies of the kind of jokes that horrible people tell in earnest. The show’s abuse of Meg is of a piece with this. Taken as a whole, Family Guy says less about how society treats women specifically and more about America’s deep unease about the fact that it is a mixed-race society. One way to cope with the fact of human variety is to laugh at it in a joyous spirit. Another way is to nervously make cruel jokes about minorities. Family Guy is a lowbrow show. It takes the second route while claiming to take the first. Even the most dismal Simpsons episode is warmer and more sophisticated. The two shows aren’t really doing the same thing at all.

Ted Cruz!

I did indeed catch reports of Ted “Toad of Toad Hall” Cruz’s remarks at CPAC back in February, to wit: “The Democrats are the party of Lisa Simpson and Republicans are happily the party of Homer, Bart, Maggie and Marge.” The thing is, I think he’s absolutely right. On some basic level, Cruz has intuited that post-Golden Age Simpsons consistently punishes excellence and rewards crassness, ignorance, and stupidity. In this, post-Golden Age Simpsons is exactly like the contemporary Republican Party. Let us not forget that the GOP in the 21st century has been able to field, as its lone “intellectual,” one Paul Davis Ryan, a man who once looked like merely the creepiest counselor at a summer camp for girls, but who now (after a year as Trump’s lickspittle) looks like the mortuary assistant at his own funeral. For attempting to appear “smart” (with his PowerPoint presentations and his thousand-page “tax plans”), Ryan has had the moral and intellectual shit beaten out of him by the rest of Trump’s GOP. You’d almost feel sorry for him. But not really.

(Image credit: @isikbreen)

6000 Words?!? Are You Out of Your Mind?!

To the vocal minority who complained that the post is too long, I say: The internet has ruined your ability to concentrate, Sir or Madam, and you should direct your complaints to the man responsible for inventing the internet in the first place, former president Al Gore.

“That’s Just, Like, Your Opinion, Man”

Indeed it is, Sir or Madam! Indeed it is. In fact, some people might say that “presenting an informed individual opinion” is the whole point of criticism to begin with. It seems rather strange that I would need to explain this to you, an adult person who has presumably read works of criticism before. But it takes all sorts!

You Clearly Have a Feminist Bias.

That’s one way of looking at it.

“Your Twitter bio is cringe, how can all your opinions be correct, you smug liberal dolt”

I’m afraid I don’t have time to teach you the rudiments of irony, my friend, but I wish you every happiness in life – truly I do. Life isn’t easy for anyone, and I hope that abusing strangers on the internet has brought you some measure of peace.

“u should kill yourself”

No, I don’t think I will, actually. Thanks for reading, though!

[UPDATE] Hey, What About The Recent Controversy Over Apu Being a Racial Stereotype?

Yeah. I mean, Apu is a racial stereotype. There are plenty of racial stereotypes in The Simpsons. As an Irish person, I generally enjoy the show’s representations of Irish people (“Whacking Day was originally started in 1924 as an excuse to beat up the Irish!” “Aye, ’tis true. I took many a lick. But sure ’twas all in good fun!”). But Irish people are white Westerners. I completely understand Hari Kondabolu’s argument, in The Problem with Apu, that Apu has not served Indian people particularly well, over the years. The current debate is about the show’s response to Kondabolu’s critique. In the most recent episode, “No Good Read Goes Unpunished” (Season 29 Episode 15), Marge tries to rewrite an offensive book she loved as a child, and finds that she has destroyed its magic. I’ll let the New York Times describe the key scene:

At one point, Lisa turns to directly address the TV audience and says, “Something that started decades ago and was applauded and inoffensive is now politically incorrect. What can you do?” The shot then pans to a framed picture of Apu at the bedside with the line, “Don’t have a cow!” inscribed on it.

Just so we’re all on the same page, here’s what happens in this scene: Lisa, the show’s embodiment of progressive liberalism, is made to say “Fuck off” to a progressive/liberal critique of the show. The Simpsons may or may not be obliged to respond to Kondabolu’s argument about Apu (we can argue about that). But it’s incredibly depressing that it chose to respond in such a dismissive, reactionary way.

And that it should choose Lisa to deliver the key speech: that’s incredibly depressing, too.

[UPDATED UPDATE] Early in “No Good Read Goes Unpunished,” Lisa is shown reading With No Apologies, the memoirs of Arizona Senator and 1964 presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. “He opposed the religious right,” Lisa notes, approvingly. Of course, Goldwater also believed that the US should drop nuclear weapons on the North Vietnamese and suggested that the only problem with the John Birch Society was nutty leadership. I’m starting to think we’re being trolled.

Seven Types of Atheism by John Gray

My review of John Gray’s superb new history of atheist thought (Allen Lane) appears in today’s Sunday Business Post Magazine. Here’s a short excerpt:

There are no gods. There is no such thing as “humanity” – only human beings with disparate beliefs and desires. The soul and its modern analogue, the self, are illusions. There can be no such thing as a universal morality. Human beings are no different from animals. We may never be able to understand the universe in which we live. Science and technology will not deliver us from suffering or death. Human beings are not rational creatures. History is not leading anywhere in particular. Old evils, apparently stamped out, will return in new guises. There is no such thing as moral progress.

This list of heresies is a crude distillation of the thought of John Gray, the author of Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals (2002), Black Mass: Apocalyptic Religion and the Death of Utopia (2007), The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths (2013), and The Soul of the Marionette: A Short Enquiry into Human Freedom (2015). For many years a right-leaning political philosopher – he taught at Oxford and at the London School of Economics – Gray has become, with these books, perhaps the one truly indispensable thinker of the 21st century.

April 5, 2018

The Dawn of Man (A New Short Story)

I’m teaching Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey next week, and while I was watching the “Dawn of Man” prologue to the movie – in which the apes discover the idea of using tools under the influence of the humming monolith – I had an idea for a short story narrated by the ape who first discovers how to smash things with bones. And here it is!

*

Look, I feel bad about the tapir. I do. But at the time, it wasn’t really a question of empathy, or of cross-species consciousness, or what have you. No, it was much more a question of discovery. Do you get me? The tapir was minding his own business, I accept that. He had as much right to graze the savannah as any of us. But once you get an idea into your head, that idea takes on a life of its own, you know? And then all of a sudden you find yourself clubbing a tapir to death and chowing down on raw tapir-meat and people are saying, What’s your problem with tapirs, Largest Ape in the Tribe? And I’m like, Hey the idea took me where it took me, all right? I think you can see where I’m coming from.

Or maybe you can’t. I mean the whole idea of “ideas” as such is still pretty new, right? In the sense that I’m the first hominid ever to actually have one – an idea, I mean. For a long time none of us had any idea about ideas. There we were, sleeping in caves, picking the nits out of each other’s fur, and generally going about our lives in a peaceable fashion – if you discount the occasional shrieking-match or skirmish with a rival tribe. (And can I just say while I’m on the subject, the Tribe from Under the Big Tree by the Next Watering-Hole Along? Those guys can go fuck themselves. Seriously. I’m still pretty pissed off about that fruit-stealing incident from several roughly equal periods of darkness and light ago, and I think Second-Largest Ape in the Tribe will support me on that.) My point is that before I picked up that bone and started whacking shit with it, the closest any of us had come to an idea was stuff like have sex now, or get away from my fruit. And to call stuff like that ideas is really – let’s be honest – pretty generous. Nope, I was the first real ideas-ape – that’s my claim to fame – and even though I really only managed to come up with one idea, I think you’ll agree it’s a doozy. It’s certainly made a big difference around here, I don’t have to tell you.

Let me recreate the moment. It’s your average day on the plains. Hot Bright Thing is doing its hot, bright thing up there above us all. Everyone’s just lazing around – we had a real issue with morale on those hot, bright days, a real lassitude problem. Nobody could even be bothered to get worked up about food, or fucking, or anything. I tried to get Third-Largest Ape and Sexual Partner of Third-Largest Ape to come for a bit of a forage with me, but they waved me away and scuttled off to hide in the shadow under a rock, the lazy bastards. So there I was, compelled to go off foraging on my own. And I had no luck. All I could find was a big pile of bones – the bleached bones of some poor tapir, lying there in the dust. I’ll say it again: I have no problem with tapirs, it’s not a tapir thing, it just so happened that it was a tapir bone that gave me the idea – the World’s First Idea, the thing that’s changed everything, if I do say so myself.

But I’m getting ahead of my story. The big thing back then – I’m sure you all remember – was Huge Grey Block. This was what most of my fellow hominids were doing with their time, back in the pre-ideas era: hanging around Huge Grey Block, which – as we all know – just appeared one morning outside our cave, sitting there and doing bugger-all. Yeah, Huge Grey Block had become a real hobby, a real pastime, around then. Second-Largest Ape in the Tribe and Smallest Ape in the Tribe were the real project leaders on this, to give credit where it’s due. Their thing was jumping around Huge Grey Block and screaming at it – maybe touching it a little bit, trying to see if it was edible, I guess.

Me, I was skeptical. Huge Grey Block had already been around for three or four roughly equal periods of light and darkness, and it still didn’t seem to be doing a whole lot with its time. “What about Humming Noise,” Smallest Ape in the Tribe would grunt, whenever I raised this point. Which, fair enough: Huge Grey Block did seem to have this humming noise thing going on. Got right into your inner ear, that noise. Seemed to mess around with the mush inside your head, in some strange way. It was getting to be kind of a drag, or so I felt.

So I’d be lying if I said my foraging expedition that day didn’t have something to do with getting away from Huge Grey Block and Humming Noise. Mainly I just wanted some peace and quiet, plus maybe a snack if there was anything to be had. But as I mentioned, all I found was a bunch of tapir bones. It was depressing. No fruit trees, no small scurrying animals, no water. Just dry bones. It was a rough day to be a hungry hominid, and no mistake.

Anyway. There I am, sitting among the bones, feeling pretty blue. And I find my fingers have curled around one of the larger bones in the pile. Nothing remarkable there. Nothing that hasn’t happened a hundred times before. It’s quite nice, actually, the feel of clean bone on your skin. Smooth and warm, with little ridges and cracks under your fingertips. It passes the time, in any event.

But something was different that day. I know, I know – I’ve told this part of the story so often that it’s in danger of becoming a cliché. But to some of the younger apes it may still be fresh. Some of you young tool-users may want to know what it was like, discovering the concept of tool-use for the very first time. So I’m sitting there with my fingers curled around this bone. And without even really thinking about it, I find I’m touching the bone harder than usual – my fingers have curled around so that they’re actually touching the palm of my hand, with (and this is the crucial point) the bone sort of gripped or clasped in the middle. Of course now we know what a revolutionary concept this is – it has, after all, given us all sorts of other ideas, like “lifting” and “carrying,” et cetera – but at the time, I freely admit, I just sort of went, “Huh.”

So here’s this bone in my hand. And about five seconds later, I’m like: This bone is IN MY HAND. I was like, Wow. Okay. That’s new. And then I just did it: I used my arm to lift the bone up and put it above my head. And it stayed there.

It seems like nothing, now – like no big deal. But at the time, if you had told one of your fellow hominids: “Hey, I just used my hand to move a bone and now the bone is above my head and it’s staying there,” they would have been all like, “What the fuck are you talking about, Largest Ape in the Tribe? That’s impossible!” And when I did tell people, it absolutely blew their minds.

So I’m there, holding this bone aloft. And I asked myself the obvious question: What next? In the event, it was purely a matter of logic: I moved the bone back down again. And I want you to know, as you sit there listening to me, that I had absolutely no idea what would happen next. And this, I think, is really the essence of having an idea. You have an idea, and all bets are off. You just don’t know what you’re getting into, once you set an idea loose in the world. Superfically, I might have been waving a bone around out there on the savannah under the Hot Bright Thing, but really I was in the dark. But of course I was. This was cutting-edge stuff – the front line of technology. Completely unpredictable. It could have gone disastrously wrong. I could have been killed. There was just no way of knowing.

Three seconds later, I’m looking at a smashed tapir skull and thinking, Did I do that? Naturally, I was dubious. The skull could easily have smashed by itself – independently of the thing I was doing with my fingers and my arm and the bone. There was only one way to confirm my suspicions. I moved the bone up and down with my arm again. Boom! Another pile of smashed skull bits.

By this stage, I was starting to feel pretty good. We all know the feeling by now, of course – the good feeling that comes from smashing things with a bone. But at the time I was scared shitless. I was experiencing something no one had ever experienced before – and that’s always a mindfuck.

I’ll skip over the next few hours of experimental confirmation, which were mostly taken up with smashing more tapir bones and reassuring myself that the good feeling I had about doing this was normal. Since that morning, the conclusions I reached have been pretty thoroughly verified by real-world testing – if you smash something with a bone, it stays smashed, and all that. But there was more to come. Sure, I’d had a breakthrough. But there was still the question of practical application.

That’s when I saw the tapir. Now I’ll be the first to admit that one of the most serious consequences of the widespread adoption of my idea has been that the tapirs are now afraid of us and consequently much more difficult to hunt. I take full responsibility for that. I do. But I would argue, in counterpoint, that the bone-to-the-head method of killing tapirs has made the whole process about a million times more efficient. So what we’ve lost in tapir access, we’ve gained in tapir killability. Which I think is a real, undeniable improvement. But you all know my feelings on this and I won’t bore you with them once again.

Really I just want to remind everyone that it’s not a tapir thing specifically. I really do think that my idea has broader applications than just tapir-killing, and I’ve made the point many times that we need to look into experimenting with smashing other animals over the head with bones. The reason I started with a tapir is that a tapir happened to cross my path at the key moment. That was it. If we do nothing but kill tapirs, it really is going to seem like we’re just anti-tapir as a matter of policy, and that’s going to make us look bad.

But anyway. Sometimes people will ask me, “Hey, Largest Ape in the Tribe, now that you’ve come up with an idea – and, some would argue, with the very idea of ideas as such – where do you think we’re headed, as a society? What’s the next idea going to be?” And I don’t know if I have any good answers to this question. There are always rumours, of course. Just the other day, Not the Smallest Ape in the Tribe was talking about Tribe From the Other Side of the River, who have apparently diversified into using rocks instead of bones to smash things with. It seems crazy to me, but there you go. I will say that I have no time whatsoever for those rumourmongers who claim that certain apes in certain other tribes have used bones to smash other apes over the head in some sort of power-grab or war maneuvre. I think that’s a horrifying concept and I reject it completely. Smashing animals over the head with bones is a benevolent technology. It’s liberated us from what was – let’s face it – a pretty benighted phase in our history. If people are even thinking of using smashing animals over the head for destructive purposes, then I don’t know what kind of world we’re living in.

But I’ve gone on long enough. The Humming Noise from Huge Grey Block is starting to get to me, and Hot Bright Thing is about to be replaced by Cold, Less Bright Thing, which is my signal to retire for the evening. Thanks for listening, and remember: keep your eyes open. There are ideas everywhere. You just have to know where to look.

April 2, 2018

Farther Away by Jonathan Franzen

This review first appeared in The Sunday Business Post in July 2012.

*

Jonathan Franzen is a champion complainer. He complains about BlackBerrys – which may be “sexy,” but which are also “great allies and enablers of narcissism.” He complains about televisions in airports: “a small but apparently permanent diminution in the quality of the average traveller’s life.” He complains about planned obsolescence: “WordPerfect 5.0 for DOS won’t even run on any computer I can buy now.” He complains about people using their cellphones in public: “The world ten years ago was not yet fully conquered by yak.” He complains about writers who use “comma-then”: “If you use comma-then like this frequently in the early pages of your book, I won’t read any farther unless I’m forced to.”

But unlike the great complainers of literary history – Jonathan Swift, Mark Twain, H.L. Mencken, Gore Vidal, Dwight MacDonald – Franzen doesn’t really seem to get off on complaining. Instead, he seems pained by his own compulsion to grouse about our fallen world. He doesn’t want to be that guy – he doesn’t want to be the crusty old liberal humanist who thinks that people say “I love you” too cavalierly these days and who prefers to spend his spare time birdwatching.

Franzen’s anxiety about complaining manifests itself in the unseemly amount of time he spends, in his new collection of essays, worrying about whether or not his crotchets and obsessions seem “cool.” “Cellular technology was […] free to continue doing its damage without fear of further criticism, because further criticism would be unfresh and uncool. Grampaw,” he writes in “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” an unfocused (though satisfyingly cranky) jeremiad about mobile phones and the erosion of privacy. And: “It’s very uncool to be a birdwatcher,” he frets in the opening piece, a speech delivered to a presumably baffled Kenyon College graduating class in 2011.

Well, it is very uncool to be a birdwatcher, if your definition of “cool” is whatever a twenty-year-old in skinny jeans might think is “cool.” But why should Jonathan Franzen (who is, as of this writing, 52 years old) care whether or not people think he’s cool? He has written two of the best American novels of the last twenty years: The Corrections (2001) and Freedom (2010). Time called him a “Great American Novelist.” He’s Jonathan Franzen, for God’s sake: no one else is currently writing novels that run as deep or reach as far. As a novelist, he provides the classical satisfactions of great, traditional fiction: narrative sweep, human detail, social vision. His essays, alas, are another story.

Like almost every other American novelist forced to wrestle with the ghost of David Foster Wallace (the Crown Prince of American Intellectual Self-Consciousness, who appears as a central figure in two of the pieces collected here), Franzen the nonfiction writer has become helplessly trapped in a feedback loop of self-examination: he is nervous about appearing to worry about appearing uncool, all of which makes him feel very uncool indeed. He wants to complain, but he doesn’t want to enjoy complaining too much, lest he seem like the sort of person who enjoys complaining too much.

This sort of thing has become a standard set of anxieties for the practicing American novelist, and some writers have made interesting fiction out of their wanderings in the maze of self-absorption. But in Franzen’s case it is a pity that he has allowed this endemic self-consciousness to overwhelm his literary gifts. As a novelist, he is equipped with a rare synthesizing intelligence, a great and warm capacity for satirical observation, and deep resources of empathy and cunning. As a confessional essayist, he is as nervous as an early Woody Allen character, forever apologising for himself and obscuring his subjects behind his finely elaborated literary-theoretical scruples.

“I recognise that by talking about my own work,” he writes, in an essay called “On Autobiographical Fiction,” “and telling a story of progress from failure to success, I run the risk of seeming to congratulate myself or of seeming inordinately fascinated with myself.” And yet, when Franzen gets his apologies out of the way and just tells his story, the result is a fascinating account of how he came to write The Corrections.

By far the best piece in the collection is “The Ugly Mediterranean,” a vivid, angrily articulate account of the hunting of songbirds in Cyprus and Italy, in which Franzen sets aside his concerns about seeming “cool” and simply presents the evidence, using his formidable reportorial skills.

Farther Away is a patchy sort of book, even for a collection of miscellaneous pieces: fitfully illuminating, often beautiful, more often tortured and grumpily abstruse. Its contents should be understood as by-products of Franzen’s day-job: writing novels as gripping, empathetic, and lucid as Freedom and The Corrections.

*

Bonus content: I interviewed Jonathan Franzen in 2015. Read the transcript here.

April 1, 2018

The Overstory by Richard Powers

My review of Richard Powers’s new novel, The Overstory (William Heinemann), appears in today’s Sunday Business Post Magazine. Here’s an excerpt:

Across twelve books, Powers has established himself as one of our great contemporary novelists of science. In Galatea 2.2 (1995), he told the story of a writer tasked with helping a computer to pass the Turing Test. In the National Book Award-winning The Echo Maker (2006), he wrote about a man suffering from Capgras Syndrome – the belief that your friends and loved ones have been replaced by identical replicas. And Generosity: An Enhancement (2009) was about a woman diagnosed with hyperthymia, or an excess of happiness.

Powers’s stories trace the fault-line between scientific rationalism and a literary (or even romantic) humanism – precisely the fault-line that James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis illuminates so clearly. Powers is an intensely cerebral writer. His novels are dense with ideas. They are often made up of many intricate narrative strands, carefully woven together. They are not, in other words, particularly light reading, and this reviewer freely admits to having given up on a few over the years.

March 25, 2018

Saturday Bloody Saturday by Alastair Campbell & Paul Fletcher

My review of Alastair Campbell & Paul Fletcher’s new collaboration (Orion) appears in today’s Sunday Business Post Magazine. Here’s a short excerpt:

In one of the best episodes of I’m Alan Partridge, Alan meets two Irish TV producers to discuss a project. Casting around for things he knows about Ireland, Alan settles on U2. “’Sunday Bloody Sunday,’” he says. “It really captures the frustration of a Sunday, doesn’t it? You wake up in the morning, you’ve got to read all the Sunday papers, the kids are running round, you’ve got to mow the lawn, wash the car, and you think, Sunday, bloody Sunday.”

We must presume that Alastair Campbell and Paul Fletcher are not acquainted with this particular scene. Otherwise, they might have hesitated before settling on Saturday Bloody Saturday as the title of their novel about football and IRA terrorism in 1970s England. As titles go, Saturday Bloody Saturday is classic Partridge. If it hasn’t already been flagged by the Accidental Partridge Twitter account (which catalogues real-life examples of Little-England provincialism and literalist bathos), then someone should submit it at once.

March 21, 2018

They Can’t Kill Us All: The Story of Black Lives Matter by Wesley Lowery

This review first appeared in The Sunday Business Post Magazine on January 15th, 2017.

*

During his farewell address in Chicago, on January 10th, 2017, Barack Obama talked about the (non-Republican) elephant in the room. “Race remains a potent and often divisive force in our society,” he said. “Race relations are better than they were ten or twenty or thirty years ago […] But we’re not where we need to be.”

He wasn’t kidding. On August 19th, 2014, Michael Brown, an unarmed black man, was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. Brown’s crime was negligible: he had stolen some cigarillos from a convenience store. The officer involved, Darren Wilson, fired seven bullets into Brown’s body. Wilson was never charged for the shooting. Ferguson, a suburb of St. Louis, is what they call “majority-minority”: i.e. 52% of its population is African-American. But the civic government of Ferguson – including the police department – is overwhelmingly white. Brown’s shooting sparked a conflagration: by the following evening, peaceful protests had turned violent, and a nascent movement, taking the name Black Lives Matter, had found a new cause. What the success of Black Lives Matter made unignorably clear is that the “postracial America” foreseen eight years ago by certain optimists was a dream gone sour.

In the United States, according to statistics compiled by the Washington Post, an unarmed black person is shot and killed by police officers every ten days. One of the journalists who helped to compile these stats is 26-year-old Wesley Lowery, who was on the ground in Ferguson the day after Michael Brown’s death. Sending dispatches from his laptop in a McDonald’s, Lowery was ordered by cops to clear the area; two minutes later, he was arrested. Lowery’s father is African-American. They Can’t Kill Us All, Lowery’s report on the Black Lives Matter movement, is perhaps excusably passionate and partisan. As he says: “even with a black president in office, my shade of pigment remained a hazard […] I’m a black man in America who is often tasked with telling the story of black men and women killed on American streets by those who are sworn to protect them.”

In other words, Lowery is himself helplessly implicated in the story he is telling. Despite the occasional gesture towards even-handedness, he is transparently on the side of the protestors and against “the nightly militarised response of law enforcement” to their demonstrations. They Can’t Kill Us All is a fiery hunk of committed, first-person reportage, a dispatch from the front lines of a righteous struggle. Lowery, in his ardour, sometimes gets carried away. “The bitter taste of injustice is intoxicating on the tongue of a traumatised people,” he writes, which is the sort of line that might go down well at a protest rally, but that doesn’t get us very far as analysis. Occasionally Lowery’s prose, rushing down the turnpike, gets itself involved in a collision: “A shortsighted framing, divorced from historical context, led us to litigate and relitigate every specific detail of the shooting without fully grasping the groundswell of pain and frustration fuming from the pores of the people of Ferguson – which also left us blindsided by what was to come.” Journalism may be history’s rough draft, but surely it doesn’t need to be quite as rough as this.

Lowery’s outrage confers advantages and disadvantages. It is impossible not to conclude, from a perusal of his pages, that police departments in many American cities are disfigured by racism. Hair-trigger cops, almost all of them white, shoot first and ask no questions – and, later, pay no price. The most harrowing incident Lowery relates is the death of Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio, in November 2014. Two white patrol cops, responding to reports of “a black male sitting on a swing and pointing a gun at people” in a city park, shot Rice dead two minutes after they arrived on the scene. Rice was 12 years old. His gun was a toy.

But Lowery’s passion does him, and his readers, an analytical disservice. “Black Lives Matter,” he writes, “is best thought of as an ideology.” But neither Lowery nor his interviewees can offer a persuasive account of the movement’s ideological platform. Instead, Lowery excitedly catalogues the number of times “#blacklivesmatter” has been retweeted. He relies disproportionately on events limited to social media, as if sharing a Facebook post counted as political activism.

Lowery does briefly acknowledge “the darker side of […] social media,” noting that some movement activists “had a propensity to play a bit fast and loose with the facts” – or, in plainer terms, to lie. The weasel words here are telling. In Lowery’s world of them-versus-us, they (the authorities) lie; we (the protestors) have a propensity to play fast and loose with the truth. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to Lowery that the social media landscape is a wilderness of mirrors in which nothing should be taken at face value – neither the words of your enemies nor the words of your friends. On Twitter, you can say anything you want – it will be forgotten within the hour. Just ask Donald Trump.

It’s been mooted that Trump’s ascension will transform Barack Obama into a tragic figure. But Obama’s tragedy isn’t that his successor is something like his human opposite (while Obama is urbane, Trump is vulgar; while Obama is forthright, Trump is a liar; while Obama is an intellectual, Trump is a moron; and so forth). Obama’s tragedy is that, during his Presidency, America’s half-healed racial wound was torn open once again, and began to fester. Obama is fond of quoting a remark made by Dr. Martin Luther King: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” This is a comforting thought. But it isn’t true. There is no “arc of the moral universe.” There are only human beings, who are, among other things, violent, racist, deceitful , and stubborn. Lowery, in his zeal, has glimpsed this truth only fitfully. His book is nonetheless indispensable, even as it marshals only the rudiments of a long and painful story.

Kevin Power's Blog

- Kevin Power's profile

- 29 followers