Kevin Power's Blog, page 10

May 13, 2018

The Lost Letters of William Woolf by Helen Cullen

[image error]

My review of Helen Cullen’s debut novel (Michael Joseph) appears in today’s Sunday Business Post Magazine. Here’s a short excerpt:

Back in 1979, John Irving defended Dickens against the charge that his characters were absurdly sentimental by suggesting that, well, real people are absurdly sentimental, too. And Vladimir Nabokov once remarked that “people who denounce the sentimental are generally unaware of what sentiment is.” More recently, academic critics have pointed out that the tag “sentimental” has frequently been used to deny the power and appeal of fiction written by women.

All of which is an elaborate way of saying that your humble reviewer found Helen Cullen’s The Lost Letters of William Woolf a pretty sentimental sort of book, and that it wasn’t entirely to his taste – which isn’t to say that it’s a bad book. It isn’t at all a bad book, in fact: it’s a solidly-crafted piece of commercial fiction with a high-concept hook and some well-realised characters. Its saccharine-ness (saccharinity?) is, as it were, built in: it’s a story about searching for true love; a certain amount of sentimentality is inevitable.

May 9, 2018

What I Read in 2009

Perhaps of personal archaeological interest merely – back in 2009 I kept track of every book I read. Herewith, the list, which I recently found going through a pile of old papers. A couple of notes: 1) I was freelancing back then, which meant I had much more time to read. Now that I teach full-time, I read rather less. 2) if I was reading a book for review, it’s marked (for review). 3) If I was rereading a book, it’s marked (again). 4) Books that seemed particularly good I marked with an asterisk – I don’t know if I’d necessarily find all of the asterisked books equally worthy of an asterisk now, though many of them are obviously great (Kafka, etc) or have since become part of my personal canon.

January

Lawrence Wright, The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda’s Road to 9/11*

James Ellroy, The Black Dahlia

Elmore Leonard, Get Shorty

Gilbert Adair, The Act of Roger Murgatroyd

PG Wodehouse, Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves

Ken Bruen, The Dramatist

Peter Carey, My Life As a Fake

Eoin McNamee, Twelve Twenty Three

Will Self, Feeding Frenzy

Claire Kilroy, Tenderwire

Dale Peck, Hatchet Jobs: Writings on Contemporary Fiction *

Anita Shreve, Testimony (for radio review)

Junot Diaz, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao*

February

Andrew Sullivan, Love Undetectable: Reflections on Friendship, Sex, and Survival

Peter Carey, Wrong About Japan: A Father’s Journey with his Son

Barack Obama, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream

Rajiv Chandrasekaran, Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Baghdad’s Green Zone

Paul Krugman, The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008

Bernard Lewis, The Crisis of Islam: Holy War and Unholy Terror

Noam Chomsky, Hegemony or Survival: America’s Quest for Global Dominance

Katrina vanden Heuvel, ed., A Just Response: The Nation on Terrorism, Democracy, and September 11, 2001

Peter L. Bergen, Holy War, Inc.: Inside the Secret World of Osama bin Laden

Karen Armstrong, Muhammad: A Prophet for Our Time

Alain Badiou, The Meaning of Sarkozy

Ian Buruma, Murder in Amsterdam: The Death of Theo van Gogh and the Limits of Tolerance

Barry H. Leeds, The Enduring Vision of Norman Mailer

Norman Stone, World War One: A Short History*

John Kenneth Galbraith, The Great Crash 1929

Sam Harris, The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason

March

Janet Browne, Darwin’s Origin of Species: A Biography

Garry Wills, Saint Augustine

Bill McGuire, A Guide to the End of the World: Everything You Never Wanted to Know

Jean Baudrillard, The Spirit of Terrorism & Requiem for the Twin Towers

Malcolm Gladwell, The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference

Mark Leonard, What Does China Think?

Naomi Wolf, The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women*

Tony Judt, Reappraisals: Reflections on the Forgotten Twentieth Century

Rick Moody, The Ice Storm

Fintan O’Toole, After the Ball*

Eileen Warburton, John Fowles: A Life in Two Worlds

R.F. Foster, Luck and the Irish: A Brief History of Change, 1970-2000

Michael Chabon, Maps and Legends: Reading and Writing Along the Borderlands

Richard Laymon, Allhallow’s Eve

Robert Stone, Bay of Souls

Jonathan Lethem, You Don’t Love Me Yet

Ian Buruma, The Missionary and the Libertine: Love and War in East and West

Saul Bellow, The Bellarosa Connection

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath*

April

Gene Kerrigan, Dark Times in the City (for review)

Toby Litt, I play the drums in a band called okay

F. Scott Fitzgerald, Tender is the Night

Michael Chabon, The Final Solution

Toby Litt, Exhibitionism

Toby Litt, Journey into Space

Zadie Smith, The Autograph Man

Will Self, Dr Mukti and Other Tales of Woe

James Lasdun, It’s Beginning to Hurt (for review)

Bret Easton Ellis, Glamorama

Jay McInerney, How It Ended

Jay McInerney, Model Behaviour

May

Claire Kilroy, All Names Have Been Changed

John Boyne, The House of Special Purpose

Ezra Pound, ABC of Reading

Martin Amis, House of Meetings (again)

John Gardner, The Art of Fiction

Alaa Al Aswani, Friendly Fire (for review)

Joan Didion, Democracy (again)

June

Zachary Leader, The Life of Kingsley Amis

Nick McDonell, The Third Brother

David Foster Wallace, Girl With Curious Hair

Paul Howard, We Need to Talk About Ross

Edgar Allan Poe, Spirits of the Dead: Tales and Poems

Aravind Adiga, The White Tiger

Charlaine Harris, Dead Until Dark

Aravind Adiga, Between the Assassinations (for review)

Dale Peck, Now It’s Time to Say Goodbye*

Dale Peck, Martin & John

Zadie Smith, ed., The Burned Children of America

Christopher Isherwood, All the Conspirators*

Christopher Isherwood, Lions and Shadows (again)

July

E. M. Forster, Abinger Harvest

Arundhati Roy, Listening to Grasshoppers: Field Notes on Democracy (for review)

Irvine Welsh, Reheated Cabbage (for review)

E.M. Forster, A Room With A View

Alan Moore & Kevin O’Neill, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Century 1910

Graydon Carter, ed., Vanity Fair’s Tales of Hollywood: Rebels, Reds, and Graduates and the Wild Stories Behind the Making of 13 Iconic Films

Justine Delaney Wilson, The High Society: Drugs and the Irish Middle Class

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

August

Alan Moore & Brian Bolland, Batman: The Killing Joke

Rob Long, Conversations With My Agent

Tom Stoppard, Arcadia (again)

Glenway Wescott, The Pilgrim Hawk

Henry James, Washington Square*

Henrik Ibsen, When We Dead Awaken

Bertolt Brecht, The Threepenny Opera

Albert Camus, The Plague*

Euripides (trans. WS Merwin), Iphigenia At Aulis

Yukio Mishima, The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea

Franz Kafka, The Trial*

D.H. Lawrence, Selected Letters

Diderot (trans. Jacques Barzun), Rameau’s Nephew

Marquis de Sade, Philosophy in the Boudoir

Moliére (trans. George Graveley), The Would-Be Gentleman

Aristophanes (trans. David Barrett), The Frogs

Honoré de Balzac, Old Goriot*

John Summerson, The Classical Language of Architecture*

Joseph Conrad, The Secret Agent*

D.H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover

John Carey, William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies* (for review)

Virginie Despentes, King Kong Theory

Clive James, From the Land of Shadows

John Updike, Bech at Bay*

Erich Heller, Kafka

Anita Brookner, Hotel du Lac

September

Nicholson Baker, Human Smoke: The Beginnings of World War II, the End of Civilisation*

Sebastian Faulks, A Week in December (for review)

John Updike, Due Considerations: Essays and Criticism

Dwight Macdonald, Against the American Grain *

John Banville, The Infinities*

Andrew Sullivan, The Conservative Soul: How We Lost It, How to Get It Back *

Janet Malcolm, Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice

Robert B. Parker, A Savage Place

Jonathan Littell, The Kindly Ones (unfinished; read the first 200pp)

Anne Marie Hourihane, She Moves Through the Boom

John Banville, Athena *

Mark Lilla, The Reckless Mind: Intellectuals in Politics

October

Michael Chabon, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

Rick Moody, The Black Veil (terrible)

Adam Mars-Jones, Venus Envy: On the Womb and the Bomb*

Jonah Goldberg, Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the Left from Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning *

Francine Prose, Caravaggio: Painter of Miracles

David Hare, Berlin/Wall

Thomas M. Disch, The Dreams Our Stuff is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World

Vladimir Nabokov, Bend Sinister

Vladimir Nabokov, Invitation to a Beheading

J.G. Ballard, Crash

David Hare, The Power of Yes: A Dramatist Seeks to Understand the Financial Crisis*

David Murphy & Martina Devlin, Banksters: How a Powerful Elite Squandered Ireland’s Wealth

Edmund White, My Lives

November

Martha Stout, The Sociopath Next Door: The Ruthless Versus the Rest of Us *

Fintan O’Toole, Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption Sank the Celtic Tiger*

David McWilliams, Follow the Money*

Julie O’Toole, Heroin: A True Story of Drug Addiction, Hope and Triumph

Chris Binchy, Open-Handed

E.L. Doctorow, Homer and Langley (for review)

Thomas De Quincey, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater

Blake Bailey, Cheever: A Life (for review)

Elizabeth Wurtzel, More, Now, Again: A Memoir of Addiction*

Abraham J. Twerski, M.D., Addictive Thinking: Understanding Self-Deception*

Kingsley Amis, Everyday Drinking

Vladimir Nabokov, The Original of Laura

Zadie Smith, Changing My Mind: Occasional Essays

Mark O’Rowe, Howie the Rookie *

Stephen King, The Dark Half (again)

Alan Glynn, Winterland

Stephen King, “The Mist”

December

Jason O’Toole, The Last Days of Katy French

Philip Roth, The Humbling

Philip Roth, Indignation *

Vladimir Nabokov, The Enchanter

Elizabeth Wurtzel, Prozac Nation: Young and Depressed in America – A Memoir

Colm Toibin, Love in a Dark Time: Gay Lives from Wilde to Almodovar

Mark Harrold, Parenting and Privilege: Raising Children in an Affluent Society

Margaret Atwood, Lady Oracle (165)

Len Deighton, Billion-Dollar Brain

Declan Hughes, The Wrong Kind of Blood

Harlan Ellison, The Glass Teat

Jacob Weisberg, The Bush Tragedy: The Unmaking of a President

May 6, 2018

Upstate by James Wood

[image error]

My review of James Wood’s rather excellent second novel, Upstate (Jonathan Cape), appears in today’s Sunday Business Post. Here’s a short excerpt:

Asked about his critical method, T.S. Eliot once said: “There is no method, except to be very intelligent.” In Wood’s case, there is no method, except to have superb taste. Wood’s taste isn’t infallible: he was wrong when he faulted The Corrections for being fatally implicated in the social confusions it so brilliantly recreates. And his taste isn’t particularly catholic, either: he has little to say about genres that deal with imagined futures or alternative worlds (“Since fiction is itself a kind of magic,” he once wrote, “the novel should not be magical”).

No: what Wood likes is realism. This is perhaps why so many readers find him narrow, or puritanical, or reactionary. The word “realism” carries heavy freight: it makes you think of clunking great 19th century novels, crammed full of wearisome detail about the lives of coal miners or provincial bishops. But what Wood admires is a realism that lets itself get mussed up by life – fiction that allows a disciplined prose to be torqued and “fattened” (a favourite word of Wood’s) by the textures of the given world. This is why he admires Saul Bellow above all others – Bellow, who writes, as Wood puts it, “life-sown prose […] logging impressions with broken speed.”

May 4, 2018

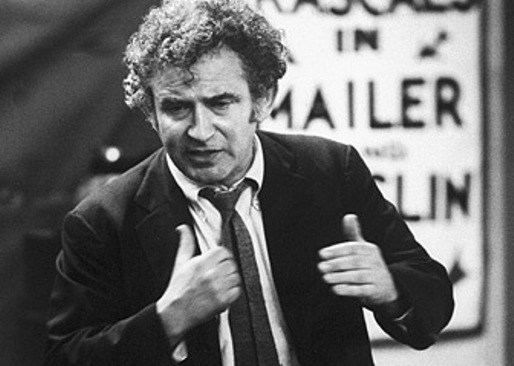

Channelling God at the DRB

A new essay of mine, “Channelling God” – looking back at Norman Mailer’s 1960s God complex, and trying to sort the Good Mailer from the Bad – is up now at The Dublin Review of Books, as part of their 100th issue. Do have a look.

At the end of the essay, I mention having met Mailer in 2006. You can read my account of that meeting here.

April 29, 2018

Last Stories by William Trevor

[image error]

My review of William Trevor’s Last Stories appears in today’s Sunday Business Post, along with reflections from Nuala O’Connor, Danielle McLaughlin, and William Wall on Trevor’s greatness and lasting influence. Here’s a short excerpt from my piece:

It may be that to the present generation of young readers, Trevor’s work (seventeen novels and sixteen collections of short stories, plus sundry plays, TV scripts, and memoirs) now has the slightly dowdy air of a time-capsule sent from a lost world: a place of loneliness, bourgeois striving, and shabby-genteel stoicism, haunted (often as not) by the spectre of ordinary evil. The times, places, and themes about which Trevor wrote so perceptively – postwar Ireland and Britain; the provinces, and the starved lives of the people therein – have been comprehensively vanquished by the forces of modernity. Or so it seems.

But if Trevor is no longer a touchstone for younger readers, this is surely a temporary state of affairs. What keeps a writer’s reputation alive beyond his or her lifetime is the regard of other writers. And other writers – people who know greatness when they see it – have always acknowledged Trevor as a master.

April 24, 2018

I Will be Voting Yes to Repeal. You Should, Too.

I’ve been reluctant to write anything about the upcoming referendum on the Eighth Amendment, mainly because I don’t think I have anything original to say about it. I also didn’t particularly want to waste a lot of time explaining why I’m entitled to an opinion on this subject (we live in a liberal democracy. Everyone is entitled to an opinion on matters affecting the common weal). I also didn’t want to add another polemic to the endless vitriolic culture-war bullshit that now defines so much of our public discourse – No campaigners are liars! Yes campaigners are smug liberals! – et cetera.

But this is important. So here are my two cents.

Because of the nature of our constitution and the nature of our history, almost every referendum we hold in Ireland is a referendum on what kind of country we want to live in. In 2015 we said, very clearly, that we wanted a country that was pluralistic and tolerant: we extended the right to marry to everyone, regardless of gender or sexual orientation. Like many people, I found this an extraordinarily moving moment. I found it so for complex reasons.

On the day of the marriage referendum, I found myself thinking about a story my mother once told me. My mother grew up in Inchicore, near the Goldenbridge orphanage – an industrial school run by the Sisters of Mercy. (You can read about the appalling history of Goldenbridge here and here.) Walking past the gates of the orphanage – this was in the mid-1960s – my mother would sometimes find handwritten notes tucked into cracks in the stone – notes from the children who lived there. “We are hungry,” these notes said. “We are beaten. We are frightened. Please help us.”

Thinking about this on the day of the marriage referendum, I wept. Because it seemed to me that the Yes result had demonstrated that Ireland was no longer the kind of country in which such things could happen.

The picture, above, shows the gates of the now-defunct Goldenbridge industrial school.

The Catholic Church campaigned for a No vote in the marriage referendum. As it has campaigned against all forms of liberalism and enlightenment for the last half-century of Irish history. As it has campaigned to preserve its putrid reputation in the wake of the Ryan and Murphy Reports, the discovery of the Tuam babies, the revelation of abuses at the Magdalene laundries and at industrial schools.

The referendum on the Eighth Amendment offers us another chance to say that the Catholic Church, long a malign parasite on the Irish body politic, has no place here any more.

It isn’t the only reason to vote Yes. It isn’t even the best reason to vote Yes. (The best reason to vote Yes is to say, powerfully and unignorably: We are a country that will never punish anyone, ever, for an accidental or unwanted pregnancy; we are a country that will never, ever let a woman die rather than abort an unviable foetus.) But it’s one of my reasons.

I’ve heard it said that some Irish men feel they have no right to vote in this referendum, or that they have no right to an opinion. (A popular argument goes: Only women should be allowed to vote, since this issue only affects them!) This is absurd, and misunderstands the nature of a liberal democracy. Ireland is ours – it is everyone’s. We all live here. What kind of country do we want it to be?

April 16, 2018

Hey, Read My Manuscript!

This piece first appeared in The Sunday Business Post in June 2016.

*

All writers start out bad. This is one of those immutable laws against which there can be no appeal. James Joyce, aged 18, wrote a dismal pastiche of Henrik Ibsen entitled A Brilliant Career, which – with a Dedalian flourish – he dedicated “to my own Soul.” Gustave Flaubert, before he embarked on Madame Bovary, devoted five years to the composition of a chaotic 800-page historical fantasia called The Temptation of St. Anthony. And – to descend, rather precipitously, the ladder of literary merit- I spent much of my twenty-second year writing a 400-page supernatural thriller set in a fictionalised version of my secondary school – a farrago blended of equal parts John Fowles, David Lynch, and my own naive incompetence. Everybody starts out bad. That’s just the way it is.

But there are always people who think of themselves as exceptions. Toby Litt, writing in The Guardian recently, asked “What makes bad writing bad?” and concluded that the culprit is often a naive exceptionalism. “Bad writers,” Litt reckons, “often believe they have very little left to learn, and that it is the literary world’s fault that they have not yet been recognised, published, lauded and laurelled. It is a very destructive thing to believe that you are very close to being a good writer, and that all you need to do is keep going as you are rather than completely reinvent what you are doing.”

As a sometime teacher of Creative Writing, I found this poignant. Broadly speaking, the good students in a Creative Writing workshop are the ones who realise, epiphanically, that they must junk every word they’ve ever written and start again, as if from scratch. The less good students – the sad majority – are the ones who endlessly resubmit the same piece of work, glancingly rehashed, secure in the knowledge that they’re getting better. (They’re not.)

More poignantly still (to me, at least), Litt complains about a quandary familiar to all professional writers. “It’s possible that you’ve never had to read 80,000 words of bad writing. The friend of a friend’s novel. I have. On numerous occasions. […] The friend of a friend’s novel may have some redeeming features – the odd nicely shaped sentence, the stray brilliant image. But it is still an agony to force oneself to keep going.”

I know that agony. Once the world starts thinking of you as “a writer,” they begin to arrive in your inbox: the manuscripts. The long-meditated, completely unreadable manuscripts. I might mention the retired gentleman who sent me his 120,000-word philosophical treatise on why young people today are so frightening and strange. Or the aspiring chronicler who forwarded me his novel about an Australian family in which everybody loved each other and the long-cherished dynastic secret was that the pater familias hadn’t been murdered, he’d just died by accident. These manuscripts vary widely in subject matter and tone, but they tend to have one thing in common: they are all, without exception, preternaturally boring – of interest only to the writer, if even then.

I never know what to do with these manuscripts. Clearly, an honest response (“This is terrible”) is out of the question. And I’m usually too busy to offer a nuanced critique (which would be a waste of time anyway). Sometimes, shamefully, I ignore them. Occasionally, I send along some vague words of encouragement – keep writing, keep reading! But either way, I experience a twinge of guilt. Because I’ve been there – I’ve done it, too: I’ve imposed my terrible manuscripts on professional writers and asked for their help. Writing has always been a kind of guild, in which the elders help their juniors, who then pass along the favour. Isn’t this what I should be doing? I reassure myself by saying that good writers will find their way with or without my help, such as it is, and that bad writers will get nowhere even if I move the pillars of heaven to help them. But the whole thing remains a discomfiting crux – a situation in which it is almost impossible to act in good faith.

So please, for the love of God, don’t send me your manuscript – unless, of course, you happen to think it’s really, really good.

On Book Reviewing

This article first appeared in The Sunday Business Post in February 2015.

*

One of the weird minor perks of being a book reviewer is that you sometimes find yourself quoted on the covers of paperbacks. It can make you feel powerful, in a completely powerless sort of way. I sometimes like to imagine growing so influential as a reviewer that cowed marketing teams, hysterically grateful for my attention, quote even my negative assessments: “Unbelievably bad […] Barely literate. Don’t even think about buying this” – Kevin Power, Sunday Business Post. A man can dream.

Browsing in Hodges Figgis the other day, I found myself excerpted on the inside covers of two novels newly paperbacked: Damon Galgut’s Arctic Summer and Zia Hadar Rahman’s In the Light of What We Know, both of which I reviewed in these pages when they were first published last year. I enjoyed, as one does in such moments, a small thrill of complacency. But what was this? It seems that I had described both novels as “masterpieces.”

Now “masterpiece,” if we are to have any critical standards at all, shouldn’t really be the sort of word that just gets thrown around. How often does a novel appear that genuinely deserves to be called a masterpiece? But here I was, blithely acclaiming two recent novels using precisely that word. Arctic Summer and In the Light of What We Know are both very good books, no doubt about it. But are they really masterpieces? Wasn’t I, by recklessly employing this word, contributing to a general debasement of its currency?

I can tell you why I did it: writing the last paragraph of a book review is really hard. A short review of a novel needs to do several things. First, it needs to give a summary of the plot (this might seem like the easy bit, but actually describing a whole novel in a couple of sentences is a kind of minor discipline unto itself, like haiku). Second, it should provide some sense of the author’s background and general concerns. Third, there should be quotations that offer a reasonably accurate sense of the author’s prose style. Fourth, there’s the whole business of evaluation: is this novel any good? If not, why not? And if so, why? Then – and here’s where the trouble starts – you need a snappy final paragraph, to tie it all up.

And it’s here – in the final paragraph – that you find yourself reaching for words like “masterpiece.” Wrapping things up at the end of a review, you cast around for a climactic rhetorical flourish: what speechwriters call a peroration. And sometimes, in your hurry to get the damn thing filed, you slap down any old thing. If it’s a very good book – if reading it has left you with warm, fuzzy feelings of gratitude towards the author – you go big: you call it a masterpiece and click send. And in fact, “masterpiece” is the final word I used in my reviews of Arctic Summer and In the Light of What We Know. (Strangely, I find that in my review of what is almost certainly an actual masterpiece, Joseph O’Neill’s The Dog, I managed to refrain from using the word “masterpiece” altogether. Baffling.)

Mea culpa, I suppose: I didn’t try hard enough to avoid one of the most inflated of book-review clichés. (“Endings are hard” isn’t much of an excuse.) This is how evaluative criticism debases its own currency. Every time we read a good-but-not-great novel that some critic or other has called a masterpiece, our sense of the value of that word takes a hit. And lazy critics (including me) end up resembling the art teacher in The Simpsons, who sees a janitor painting the stairwell and cries, “Another triumph!”

Writing the last paragraph of this column, I find myself confronting precisely the difficulty I mentioned above – how do I go out with a bang? Maybe I shouldn’t bother. Or maybe I’ll take the lazy way out once again, and assure you that the column you’ve just read is its author’s finest work to date: almost certainly, in fact, a masterpiece.

April 15, 2018

Patrick McCabe Interview/The Problem with The Simpsons

[image error]

In today’s Sunday Business Post Magazine, I interview Patrick McCabe about his new novel, Heartland (New Island). Paywalled, I’m afraid, but here’s a short excerpt:

A certain bloody-mindedness about his work has served McCabe well, over the years. After graduating from St Patrick’s College Drumcondra, he tried to combine writing with raising a family and teaching full-time in a school in Longford. “Bit by bit I began to realise, this is very difficult. I stopped sleeping, wasn’t listening to people’s conversations. I’d about three years of that, producing nothing of any worth.” During those years he discovered that, for writers, emotional struggle is “part of the game. While everybody else is going out playing football, having a great time, here you are, gnawing away at your insides, getting paler and paler, losing weight.”

It’s easy, I suggest, for writers to get discouraged during the early years. But McCabe is having none of it. “I remember a young fella announcing to me, “I’ve writer’s block.” And I said, “I’ll give you such a kick up the arse if you don’t write.” It was the best thing for him. He was falling victim to the romance of disintegration.”

[image error]

Also in today’s Sunday Business Post Magazine, I’ve got a piece about The Simpsons and its response to Hari Kondabolu’s documentary The Problem With Apu. A wee excerpt:

When I was a teenager, in that long-ago age of innocence, the 1990s, the best thing on TV was a 23-minute animated comedy about a yellow-skinned, lower-middle-class American family who lived in a town called Springfield. It was broadcast once a week, on Sky One, at 6pm on Sunday. If you missed it, your life was over. If you were sensible, you videotaped each episode, so you could watch it again and again.

My devotion to The Simpsons, back in the ‘90s, was essentially cultic. I spoke fluent Simpsons. So did my brother. So did most of my friends. We could recite whole scenes from memory. We could recreate the precise inflections with which the actors delivered their lines. And this is true of a whole generation of Anglophone TV viewers. If you grew up in the ‘90s, you grew up with The Simpsons. It was one of the elements in which you lived.

I have, of course, written about The Simpsons before, in this blog post.

April 12, 2018

Don DeLillo at The Millions

A new essay of mine – on “DeLillo, Lethem, and the Seductive Sentence” – is up over at The Millions. Do have a look!

Kevin Power's Blog

- Kevin Power's profile

- 29 followers