Phil Simon's Blog, page 99

February 25, 2013

Why You Shouldn’t Care About Negative Reviews

I talk to many people about writing books. Often I’m at a mixer when I strike up a conversation with someone. These days, I answer the “What do you do?” question with one word and two syllables: writer.

First-time or prospective authors often have many misconceptions about the publishing world. I certainly did four years ago. It’s not uncommon for authors to be outraged when someone takes to slamming them online, whether it’s on social media, Amazon, GoodReads, or any number of different sites.

As my fifth book nears release, I am certain of very few things–one of which is that someone will hate it and give me the dreaded one-star review. While I’m proud of Too Big to Ignore, I sincerely doubt that it will meet with universal acclaim.

So what?

Ultimately, any given review doesn’t matter–and that includes my own opinions. Who cares if I think that Girls is terrible and that Homeland is wildly overrated? Clearly not the show’s fans, actors, writers, directors, and for that matter the public at large.

Crtics have excoriated Rush, Marillion, Dream Theater, and many of my favorite bands over the years. That hasn’t stopped each group from persevering for more than two decades each (and nearly four in the case of Rush). One reviewer famously wrote that Rush lead singer Geddy Lee had a “high-pitched voice like a a hamster on helium.”

Don’t welcome negative reviews, but don’t fear them either. The fleas come with the dog.

February 24, 2013

Data Journalism

What’s the impact of Big Data on journalism?

To be sure, there will still be disputed stories that ultimately hinge upon “he said, she said.” More and more, however, data will be able to tell more of the story. It’s a point that I make in Too Big to Ignore.

Elon Musk recently went on the offensive, attempting to prove that the The New York Times got it wrong. His smoking gun: the data–sort of. In What the Tesla Affair Tells us About Data Journalism, Taylor Owen writes that, “Tesla didn’t release the data from the review. Tesla released [its] interpretation of the data from the review.” [Emphasis mine.]

Big difference. David Brooks of The New York Times is right. Data always must be viewed in context–and Big Data is no exception. And Mark Twain’s quote about damned lies and statistics still holds.

Simon Says

Big Data will continue to help us understand what happened and why. Don’t think for a minute that Big Data won’t affect journalism.

February 21, 2013

Innocentive Webinar on Big Data and Open Innovation

On March 26th at 11 am EST, I’ll be hosting a webinar on Innocentive.

Event title: Harnessing the Power of Big Data to Rapidly Solve Important Challenges

To register, click here.

Book Trailer for Too Big to Ignore

Here’s the book in under five minutes. Props to my spectacular video guy, Joe Buquicchio of Chrome Video Productions.

Props to my spectacular video guy, Joe Buquicchio of Chrome Video Productions.

February 15, 2013

Boston Gets Big Data

The following is excerpted from Too Big to Ignore: The Business Case for Big Data. John Wiley & Sons will be publishing this in early March of 2013. This excerpt originally ran on Huffington Post.

At some point in the past few years, Thomas M. Menino (Boston’s longest-serving mayor) realized that it was no longer 1950. Perhaps he was hobnobbing with some techies from MIT at dinner one night. Whatever his motivation, he decided that there just had to be a better, more cost-effective way to maintain and fix the city’s roads. Maybe smartphones could help the city take a more proactive approach to road maintenance. To that end, in July 2012, the Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics launched a new project called Street Bump, an app that:

Allows drivers to automatically report the road hazards to the city as soon as they hear that unfortunate “thud,” with their smartphones doing all the work.

The app’s developers say their work has already sparked interest from other cities in the U.S., Europe, Africa and elsewhere that are imagining other ways to harness the technology.

Before they even start their trip, drivers using Street Bump fire up the app, then set their smartphones either on the dashboard or in a cup holder. The app takes care of the rest, using the phone’s accelerometer — a motion detector — to sense when a bump is hit. GPS records the location, and the phone transmits it to a remote server hosted by Amazon Inc.’s Web services division.

But that’s not the end of the story. It turned out that the first version of the app reported far too many false positives (i.e., phantom potholes). This finding no doubt gave ammunition to the many naysayers who believe that technology will never be able to do what people can and that things are just fine as they are, thank you. Street Bump 1.0 “collected lots of data but couldn’t differentiate between potholes and other bumps.” After all, your smartphone or cell phone isn’t inert; it moves in the car naturally because the car is moving. And what about the scores of people whose phones “move” because they check their messages at a stoplight?

To their credit, Menino and his motley crew weren’t entirely discouraged by this initial setback. In their gut, they knew that they were on to something. The idea and potential of the Street Bump app were worth pursuing and refining, even if the first version was a bit lacking. Plus, they have plenty of examples from which to learn. It’s not like the iPad, iPod, and iPhone haven’t evolved over time.

Enter InnoCentive Inc., a Massachusetts-based firm that specializes in open innovation and crowdsourcing. (We’ll return to these concepts in Chapters 4 and 5.) The City of Boston contracted InnoCentive to improve Street Bump and reduce the number of false positives. The company accepted the challenge and essentially turned it into a contest, a process sometimes called gamification. InnoCentive offered a network of 400,000 experts a share of $25,000 in prize money donated by Liberty Mutual.

Almost immediately, the ideas to improve Street Bump poured in from unexpected places. Ultimately, the best suggestions came from:

A group of hackers in Somerville, Massachusetts, that promotes community education and research

The head of the mathematics department at Grand Valley State University in Allendale, Mich.

An anonymous software engineer

The result: Street Bump 2.0 is hardly perfect, but it represents a colossal improvement over its predecessor. As of this writing, the Street Bump website reports that 115,333 bumps have been detected. What’s more, it’s a quantum leap over the manual, antiquated method of reporting potholes no doubt still being used by countless public works departments throughout the country and the world. And future versions of Street Bump will only get better. Specifically, they may include early earthquake detection capability and different uses for police departments.

Street Bump is not the only example of an organization embracing Big Data, new technologies, and, arguably most important, an entirely new mind-set. With the app, the City of Boston was acting less like a government agency and more like, well, a progressive business. It was downright refreshing to see.

Crowdsourcing roadside maintenance isn’t just cool. Increasingly, projects like Street Bump are resulting in substantial savings. And the public sector isn’t alone here. As we’ve already seen with examples like Major League Baseball (MLB) and car insurance, Big Data is transforming many industries and functions within organizations.

Chapter 5 will provide three in-depth case studies of organizations leading the Big Data revolution.

To order the book on Amazon, click here.

February 14, 2013

Table of Contents from Too Big to Ignore

Big Data Is Not Perfect

I can think of few companies that “do” Big Data better than Google. Case in point: the company’s oft-cited ability to predict the flu better than the CDC. Its interesting to note, though, that Google Flu recently failed to provide accurate estimates. From a Nature.com article:

When influenza hit early and hard in the United States this year, it quietly claimed an unacknowledged victim: one of the cutting-edge techniques being used to monitor the outbreak. A comparison with traditional surveillance data showed that Google Flu Trends, which estimates prevalence from flu-related Internet searches, had drastically overestimated peak flu levels. The glitch is no more than a temporary setback for a promising strategy, experts say, and Google is sure to refine its algorithms. But as flu-tracking techniques based on mining of web data and on social media proliferate, the episode is a reminder that they will complement, but not substitute for, traditional epidemiological surveillance networks.

For those who think that Big Data knows all, we’re not there yet–and we may never yet there. Big Data is a club in the bag; it is not omniscient. Knowing much should never be confused with knowing all.

February 13, 2013

Exceprt from Too Big to Ignore

My 23rd Inc. Magazine article is now live. Here it is.

The following is excerpted from Too Big to Ignore: The Business Case for Big Data. John Wiley & Sons will be publishing this in early March 2013.

Much like the baseball revolution pioneered by Billy Beane, car insurance today is undergoing a fundamental transformation. Just ask Joseph Tucci. As the CEO at data storage behemoth EMC Corporation, he knows a thing or 30 about data. On October 3, 2012, Tucci spoke with Cory Johnson of Bloomberg Television at an Intel Capital event in Huntington Beach, California. Tucci talked about the state of technology, specifically the impact of Big Data and cloud computing on his company–and others. At one point during the interview, Tucci talked about advances in GPS, mapping, mobile technologies, and telemetry, the net result of which is revolutionizing many businesses, including car insurance. No longer are rates based upon a small, primitive set of independent variables. Car insurance companies can now get much more granular in their pricing. Advances in technology are letting them answer previously unknown questions like these:

Much like the baseball revolution pioneered by Billy Beane, car insurance today is undergoing a fundamental transformation. Just ask Joseph Tucci. As the CEO at data storage behemoth EMC Corporation, he knows a thing or 30 about data. On October 3, 2012, Tucci spoke with Cory Johnson of Bloomberg Television at an Intel Capital event in Huntington Beach, California. Tucci talked about the state of technology, specifically the impact of Big Data and cloud computing on his company–and others. At one point during the interview, Tucci talked about advances in GPS, mapping, mobile technologies, and telemetry, the net result of which is revolutionizing many businesses, including car insurance. No longer are rates based upon a small, primitive set of independent variables. Car insurance companies can now get much more granular in their pricing. Advances in technology are letting them answer previously unknown questions like these:

Which drivers routinely exceed the speed limit and run red lights?

Which drivers routinely drive dangerously slow?

Which drivers are becoming less safe–even if they have received no tickets or citations? That is, who used to generally obey traffic signals but don’t anymore?

Which drivers send text messages while driving? (This is a big no-no. In fact, texting while driving [TWD] is actually considerably more dangerous than DUI. As of this writing, 14 states have banned it.)

Who’s driving in a safer manner than six months ago?

Does a man with two cars (a sports car and a station wagon) drive each differently?

Which drivers and cars swerve at night? (This could be a manifestation of drunk driving.)

Which drivers checked into a bar using FourSquare or Facebook and drove their own cars home (as opposed to taking a cab or riding with a designated driver)?

Thanks to these new and improved technologies and the data they generate, insurers are effectively retiring their decades-old, five-variable underwriting models. In their place, they are implementing more contemporary, accurate, dynamic, and data-driven pricing models. For instance, in 2011, Progressive rolled out Snapshot, its Pay As You Drive (PAYD) program. PAYD allows customers to voluntarily install a tracking device in their cars that transmits data to Progressive and possibly qualifies them for rate discounts. From the company’s site:

How often you make hard brakes, how many miles you drive each day, and how often you drive between midnight and 4 a.m. can all impact your potential savings. You’ll get a Snapshot device in the mail. Just plug it into your car and drive like you normally do. You can go online to see your latest driving details and projected discount.

Is Progressive the only, well, progressive insurance company? Not at all. Others are recognizing the power of new technologies and Big Data. As Liane Yvkoff writes on CNET, “State Farm subscribers self-report mileage and GMAC uses OnStar vehicle diagnostics reports. Allstate’s Drive Wise goes one step further and uses a similar device to track mileage, braking, and speeds over 80 mph, but only in Illinois.”

So what does this mean to the average driver? Consider two fictional people, both of whom hold car insurance policies with Progressive and opt in to PAYD:

Steve, a 21-year-old New Jersey resident who drives a 2012, tricked-out, cherry red Corvette

Betty, a 49-year-old grandmother in Lincoln, Nebraska, who drives a used Volvo station wagon

All else being equal, which driver pays the higher car insurance premium? In 1994, the answer was obvious: Steve. In the near future, however, the answer will be much less certain: it will depend on the data. That is, vastly different driver profiles and demographic information will mean less and less to car insurance companies.

Traditional levers like those will be increasingly supplemented with data on drivers’ individual patterns. What if Steve’s flashy Corvette belies the fact that he always obeys traffic signals, yields to pedestrians, and never speeds? He is the embodiment of safety. Conversely, despite her stereotypical profile, Betty drives like a maniac while texting like a teenager.

In this new world, what happens at rate renewal time for each driver? Based upon the preceding information, Progressive happily discounts Steve’s previous insurance by 60 percent but triples Betty’s renewal rate. In each case, the new rate reflects new–and far superior–data that Progressive has collected on each driver.

Surprised by his good fortune, Steve happily renews with Progressive, but Betty is irate. She calls the company’s 1-800 number and lets loose. When the Progressive rep stands her ground, Betty decides to take her business elsewhere. Unfortunately for Betty, she is in for a rude awakening. Allstate, GEICO, and other insurance companies have access to the same information as Progressive. All companies strongly suspect that Betty is actually a high-risk driver; her age and Volvo only tell part of her story–and not the most relevant part. As such, Allstate and GEICO quote her a policy similar to Progressive’s.

Now, Betty isn’t happy about having to pay more for her car insurance. However, Betty should in fact pay more than safer drivers like Steve. In other words, simple, five-variable pricing models no longer represent the best that car that car insurance companies can do. They now possess the data to make better business decisions.

Big Data is changing car insurance and, as we’ll see throughout this book, other industries as well. The revolution is just getting started.

To order the book on Amazon, click here.

Click here to read the article on Inc.

February 12, 2013

Jargon Watch: Big Data as a Service

I’ve written before about how much I despise business jargon. (Here’s another link on the subject.) Every day, I’ll read a post or watch an interview on TV in which a talking head repeatedly and unnecessarily drops atrocities like “form factor”, “use case”, “price point”, “synergy”, or some other completely overused or bastardized term. There are some folks on Bloomberg West that I’ll routinely skip because they can only speak in buzzwords.

Jargon makes me cringe–and I’m hardly the only one who feels this way. “Jargon masks real meaning,” says Jennifer Chatman, management professor at the University of California-Berkeley’s Haas School of Business in a Forbes’ piece. “People use it as a substitute for thinking hard and clearly about their goals and the direction that they want to give others.”

Jargon and New Ideas

I’ve been told that I’m a very effective public speaker, and I’d bet that many of the compliments I receive stem from the fact that I speak in plain English. Yet, my last two books have focused on platforms and Big Data, terms have the potential to confuse people. This begs the question: How do you convey legitimately new ideas without sounding like a buffoon?

It’s a tricky one. Mid-market CXOs are often loathe to spend money on technologies that can actually–and significantly–help their organizations because they’re afraid. They justifiably don’t want to drop major coin on an over-hyped, flash-in-the-pan application or system. When something sounds like jargon, they hold on to their wallets.

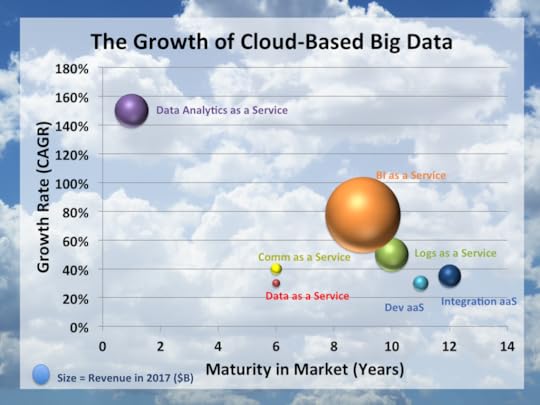

Check out the figure on the right graphic from the Infochimps’ blog. I worry about everything being labeled “as a service.” Plenty of people don’t understand Big Data as it is. Throwing “as a service” on top of it might perplex people even more.

Simon Says

I get it. “As a service” signifies that the work is effectively being done in the cloud. Organizations need not spend oodles on expensive hardware, plus they can scale as needed. Amazon’s AWS, for instance, allows organizations to buy just as much compute power as they need–no more, no less. Finally, it’s downright difficult to create a pithy but meaningful phrase for a new way of doing things, especially in a 140-character world.

At the same time, though, by overusing certain terms and bastardizing others, software vendors and consultancies run the very real risk of alienating current and prospective clients. My advice to them: use your terms sparingly. You won’t get unlimited bites at the apple.

Feedback

What say you?

This post was written as part of the IBM for Midsize Business program, which provides midsize businesses with the tools, expertise and solutions they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

This post was written as part of the IBM for Midsize Business program, which provides midsize businesses with the tools, expertise and solutions they need to become engines of a smarter planet.

February 11, 2013

Big Data and Job Creation

I profile a bunch of companies in the new book, one of which is Cleveland healthcare Big Data start-up Explorys.

I can think of few industries that can benefit more from Big Data than healthcare. There’s far too much waste and inefficiency in sector responsible for an astonishing one-sixth of the US economy–and growing at twice the rate of inflation.

Of course, there are legitimate privacy and security concerns with making this type of information available. It’s a point that I make in the new book.

That aside for a moment, Big Data is creating what I believe are very interesting jobs. To read more about this, check out this Cleveland.com article. I’m quoted in it.