Oxford University Press's Blog, page 271

March 13, 2018

Ten virtual reality games that simulate altered states

The recent resurgence of virtual reality (VR) has seen an exciting period of innovation in the format, as developers explore the fresh new possibilities that it brings. VR differs from the video games you might play on a standard television in that the head-mounted display engulfs the visual field, producing a more immersive sensory experience. In VR, not only can you see a virtual environment, but you can also turn your head to look around it. Many games use this capability to transport the player into strange virtual worlds, or see the hallucinations of a virtual avatar. Some titles focus on pure sensation, while others are highly artistic, developing ideas drawn from gothic or cyberpunk literature. This list suggests ten VR games that in different ways use the medium to explore the idea of altered states:

1. Gnosis

Gnosis by Fathomable invites the player to “explore, understand… and ascend.” With a stunning synesthetic style influenced by cyberpunk authors such as William Gibson and Philip K. Dick, the game transports the user into the “memory palace” of an artificial intelligence, which they navigate and configure by connecting a lexicon in 3D space.

2. SoundSelf

Described by creator Robin Arnott as “inspired by a group-ohm on LSD,” SoundSelf uses the human voice to create visualisations that recall the spiral and funnel patterns that people may see during psychedelic drug experiences. When experienced in complete darkness, the game is intended to fuse ancient meditation techniques with modern video game hardware.

3. Affected: The Manor

Horror games are particularly powerful in VR, offering terrifying experiences that are so intense they might even be dangerous for some people. In Affected: The Manor, the player must explore a haunted mansion, complete with pitch-black corridors, creaky doors, paintings that eerily move, spectral beings, and other such tropes of the gothic genre. The experience has a distinct hallucinatory quality, as the house contorts itself and seems to have a life of its own, causing the player to second-guess the reality of their perceptions.

4. Death is Only the Beginning

Produced by Virtual Awakening, Death is Only the Beginning is a VR experience like no other, which aims to simulate the dreamlike hallucinations of a near-death experience (NDE). The project draws significantly on Rick Strassman’s hypothesised explanation that “light at the end of the tunnel” experiences people may have during NDEs could be caused by endogenous release of the psychedelic molecule DMT.

5. Guided Meditation VR

Of course, other developers have sought to provide more relaxing VR experiences, with many meditation games available that aim to soothe the user. Guided Meditation VR is one such title, which recalls the Holodeck of Star Trek. The game transports the user to a virtual beach, a breezy clifftop, and several other relaxing spaces of synthetic tranquillity.

6. Microdose VR

Microdose VR is another psychedelic (or “cyberdelic”) project, which has been sited at electronic dance music festivals such as Coachella. Many of us probably played with paints or crayons as children — Microdose VR taps into the joy of such unstructured play, by allowing the user to creatively paint with multi-coloured particle effects. It’s like Tilt Brush… on acid!

7. Rez Infinite

The original Rez was a cult-classic on the Sega Dreamcast and Sony Playstation 2 back in the early 2000s. Using flat-shading and a wireframe style that recalled the classic science-fiction movie Tron (1982), the game was an “on-rails” shooter that incorporated a cool techno soundtrack with music by Adam Freeland, Ken Ishii, and others. Rez Infinite updates the experience and brings it into VR, providing one of the most acclaimed big-budget titles to date.

8. Dionysia

Psych-Fi’s Dionysia is another title that aims to offer audiences at music festivals mini-excursions into VR, enriching events such as the Liverpool International Festival of Psychedelia with something a little different. Dropping on the headset transports you into a melting alien world that is fittingly reminiscent of prog-rock album artwork from the 1970s.

9. Squarepusher “Stor Eiglass”

Throughout his career, Warp Records artist Squarepusher has been pushing the boundaries of electronic music through his high-tech stage shows of funk-bass wizardry and rinsed-out-yet-scholarly jungle beats; a bit like the Björk of rave music. Stor Eiglass is his collaborative foray into VR in the form of a 360 music video, which sends the viewer on a turbocharged-ride through a candy coloured psychedelic world. Could this be Yellow Submarine for the 21st Century?

10. TAS “The Canyon”

TAS (The Adventurous Spark) is a VJ known for his outstanding video mapping shows at psy-trance parties and festivals. The Canyon demonstrates his importance as one of the most interesting underground visual artists to emerge in recent years, by providing a short journey through intricate neon structures reminiscent of aquatic lifeforms and bioluminescence.

Gnosis

Image from the VR game Gnosis.

Gnosis

Image from the VR game Gnosis.

Gnosis

Image from the VR game Gnosis.

Gnosis

Image from the VR game Gnosis.

Gnosis

Image from the VR game Gnosis.

Gnosis

Image from the VR game Gnosis.

Gnosis

Image from the VR game Gnosis.

Gnosis

Image from the VR game Gnosis.

Featured image credit: Gnosis by Robert Bogucki/Fathomable, 2018. Image used with permission.

Slideshow images: By Robert Bogucki/Fathomable, 2018. Images used with permission.

The post Ten virtual reality games that simulate altered states appeared first on OUPblog.

March 12, 2018

Professionalizing leadership — education

Barbara Kellerman looks at three crucial areas of learning leadership; leadership education; leadership training; and leadership development. In this post, she discusses the importance of leadership education and how it should be approached and improved.

In the last forty years the leadership industry has burgeoned beyond anyone’s early imaginings. Learning to lead has become a commonplace, in each of the different sectors; in every type of institution and organization; and in higher education, at both the undergraduate and graduate levels.

But if teaching how to lead has become ubiquitous, learning how to lead remains mysterious. Leadership has no body of knowledge, core curriculum, or skill set considered essential. And leadership has no license, or credential, or accreditation, or certification considered by consensus to be legitimate.

This explains the yawning gap between leadership and professions, such as medicine and law, and between leadership and vocations, such as hair-dressing and truck-driving, which also require demonstrable competence before people can practice.

In the past, leadership and teaching how to lead were considered the most consequential of all human endeavors. Confucius, for instance, saw himself primarily as an educator, especially though not exclusively as a teacher of leaders. He believed that only through study – a lifetime of study – would men be able to develop their minds and bodies, their characters and capacities, to lead wisely and well. Similarly, Plato’s Republic can be thought of as a treatise on education, an education for leadership. Such an education, Plato believed, took decades to complete. Only after half a lifetime of learning could a man aspire to be a great leader, a philosopher-king.

In the present, leadership is taught, and ostensibly learned, quickly and casually. With only one major exception – the military – leadership in America is assumed a skill that can be acquired in rather short order, in a course or during a semester, in executive programs or training sessions, in classrooms or on the job. Moreover, the distinctions among leadership education, training, and development are muddled. For example, the Harvard Business School (where I teach) states that its mission is “to educate leaders who make a difference in the world.” and “to train enlightened public leaders.” Stanford’s Graduate School of Business states that its mission is to “develop innovative, principled, and insightful leaders who change the world.” Who’s to say what the differences are? While all three of these institutions intend unmistakably to graduate leaders, their means to this end would appear, at least on the surface, to be different.

Learning to lead has become a commonplace, in each of the different sectors; in every type of institution and organization; and in higher education.

I argue that all three of these pedagogies – education, training, and development – are essential to learning to lead. You must be educated to lead. You must be trained to lead. You must be developed to lead. It’s no accident that in the few American leadership learning initiatives that can legitimately claim to be excellent – such as those in the military – all three are part and parcel of the pedagogical process.

The curricula of professional schools, such as schools of medicine and law, are structured so that students are educated before they are trained and developed. Medical students study anatomy before they undertake to cut. Law students study civil procedure before they undertake to litigate. Leadership schools, even leadership programs of limited scope, should be structured to do the same.

Ironically, this was the original idea. When business schools were first established in the US, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a good liberal arts education was assumed a prerequisite to a good management education. It’s why learning to manage shifted from learning only on the job to learning, ideally, in the academy.

This raises the question of what should leaders learn? Specifically, what should a good leadership education consist of? To this question obviously are many answers, which is why the content of any leadership program should be decided by collective conversation and, ultimately, consensus. For the present purpose I will provide just three suggestions that are intended to signal substance, not to be engraved in stone.

First, a good leadership education should introduce leadership learners to great ideas. Ideas that most obviously are in the great leadership literature. What exactly is the great leadership literature? It consists primarily of classics that either are about leadership, such as Machiavelli’s Prince, or acts of leadership in and of themselves, such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. The classics of the leadership literature are of high literary quality, and they clearly have had an enduring impact. They are also timeless – and universal. They are transcendent. They include works by philosophers, pedagogues, preachers, and practitioners such as John Locke and Mary Wollstonecraft, Max Weber and Sigmund Freud, Martin Luther King and Betty Friedan, Larry Kramer and Vaclav Havel.

Second, a good leadership education should introduce leadership learners to great research. Research that has made an enduring contribution to our understanding of leadership dynamics, for example, from social sciences such as psychology, sociology, and political science. Enormous amounts of important information relevant to leadership and followership are in the social science literature, for example in work generated by Kurt Lewin and Irving Janis on group dynamics; by Stanley Milgram and Hannah Arendt on obedience to authority; and by Max Weber, Edwin Hollander, and James MacGregor Burns on leader-follower relationships.

Third, a good leadership education should introduce leadership learners to great art. Art that clearly relates to issues of power, authority, and influence and that is in great literature – think George Orwell’s short story “Shooting an Elephant.” That is in great art – think Picasso’s Guernica. That is in great music – think Beethoven’s “Eroica” (originally written for Napoleon) or, for that matter, Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.” That is in great film – from Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will to Martin Scorsese’s Wolf of Wall Street.

Most leadership programs do not now provide much, if any, leadership education. But let the perfect not be the enemy of the good! Even a modest leadership education will provide grist for the leader’s mill – reason to think before rushing to act.

Featured image credit: Classroom School Desks by Wokandapix. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post Professionalizing leadership — education appeared first on OUPblog.

How do black holes shape the cosmos?

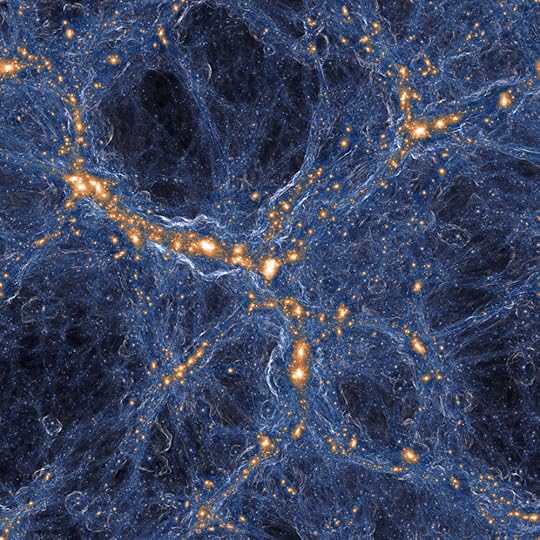

At the center of every galaxy is a supermassive black hole. Looking at the wider scale, is it possible that these gravity monsters influence the overall structure of our universe? Using a new computer model, astrophysicists have recently calculated the ways in which black holes influence the distribution of dark matter, how heavy elements are produced and distributed throughout the cosmos, and where cosmic magnetic fields originate. The project, “Illustris – The Next Generation” (IllustrisTNG) is the most ambitious simulation of its kind to date. By using supercomputers to explore the basic laws of physics, the simulations evolve a large piece of the Universe – roughly one billion light years across – from shortly after the Big Bang until the present day. Researchers use the simulations to study many of the outstanding puzzles of how our Universe, and the galaxies within it, came to be.

How do we make a realistic ‘Universe in a box’?

Our standard model for cosmology paints the picture of a Universe dominated by unknown forms of dark matter and dark energy. In order to test this scenario, we need precise predictions for how the night sky should appear. Because the light which reaches us arises from stars, diffuse gas, and accrete black holes, numerical simulations which directly evolve these three ‘baryonic’ (or normal matter) components, in addition to dark matter and dark energy, are crucial. These ‘hydrodynamical’ simulations, such as IllustrisTNG, have over the past few years become extremely powerful and predictive.

For instance, IllustrisTNG contains galaxies quite similar to the shape and size of real galaxies. The amount of stars in a given galaxy, how rapidly new stars are forming, and the balance between the ‘blue’ light of young stars and the redder light of old stars are all reasonable. For the first time, the detailed clustering pattern of galaxies in space has been shown to match large observational surveys.

We can also look at the most massive galaxies, which are thought to form through the collisions of numerous smaller galaxies. As these smaller systems are pulled together by the unrelenting attraction of gravity they are torn apart and scatter their stars in the vicinity of the massive galaxy. These “stellar halos” are hard to spot and are only now starting to be observed, and IllustrisTNG provides concrete expectations for their structure. “Our predictions can be quantitatively checked by observers,” describes Dr. Annalisa Pillepich (MPIA). “How well their properties agree provides a critical test for our current theoretical ideas of how galaxies form.”

Visualization of the intensity of shock waves in the cosmic gas (blue) around collapsed dark matter structures (orange/white). Similar to a sonic boom, the gas in these shock waves is accelerated with a jolt when impacting on the cosmic filaments and galaxies. Used with permission from ‘The IllustrisTNG collaboration‘.

Visualization of the intensity of shock waves in the cosmic gas (blue) around collapsed dark matter structures (orange/white). Similar to a sonic boom, the gas in these shock waves is accelerated with a jolt when impacting on the cosmic filaments and galaxies. Used with permission from ‘The IllustrisTNG collaboration‘.What do black holes have to do with the lifecycle of galaxies?

The most important and, often, irreversible stage in the lifecycle of a galaxy is when it “quenches” star formation, and is no longer able to convert interstellar gas into young, bright stars. Before this happens, star-forming galaxies shine brightly in the blue light of their young stars. After an abrupt change, whose exact physical mechanism and origin is still debated, the galaxy slowly fades away and joins the class of ‘red and dead’ systems. “IllustrisTNG clearly demonstrates that the only physical mechanism capable of extinguishing the star formation in these large galaxies are supermassive black holes,” explains Dr. Dylan Nelson (MPA). “These black holes release huge amounts of energy and drive ultrafast outflows of gas which can reach up to 10% the speed of light. The net result affects the entire stellar system of the galaxy, which can be billions of times larger than the comparably small black hole itself.”

What does it take to run a simulation like IllustrisTNG?

“It is noteworthy that we can accurately predict the influence of supermassive black holes on the distribution of matter out to large scales,” says principal investigator Prof. Volker Springel (HITS). “This is crucial for reliably interpreting many forthcoming measurements from large observational programs.”

To do so, the researchers developed a particularly efficient version of their highly parallel moving-mesh code AREPO and used it on the Hazel Hen machine at the High-Performance Computing Center Stuttgart – Germany’s fastest supercomputer. IllustrisTNG is the largest such project ever undertaken, and used 24,000 processors for more than two months to follow the simultaneous formation of millions of galaxies, producing more than 500 terabytes of data. The total time spent on the largest simulation so far was 35 million CPU hours, which would take 10,000 desktop computers roughly 1,000 years to accomplish. “Thanks to the German Gauss Centre for Supercomputing, we have been able to redefine the state of the art in this field,” explains Volker Springel. “Analyzing the new simulations will keep us busy for years to come, and it promises many exciting new insights into different astrophysical processes.”

Featured image credit: Rendering of the gas velocity in a thin slice of 100 kiloparsec thickness (in the viewing direction), centred on the second most massive galaxy cluster in the TNG100 calculation. Where the image is black, the gas is hardly moving, while white regions have velocities which exceed 1000 km/s. The image contrasts the gas motions in cosmic filaments against the fast chaotic motions triggered by the deep gravitational potential well and the supermassive black hole sitting at its centre. Public domain via The IllustrisTNG Collaboration.

The post How do black holes shape the cosmos? appeared first on OUPblog.

The OUP citizenship quiz

Far from fading into obscurity as the world moves towards a more interconnected and globalized future, the concept of citizenship is enjoying something of a renaissance. It is an almost constant feature in world news, as nations move to secure their positions by either welcoming or denying new citizens to cross their borders, and the contentious issue of citizenship for sale gains evermore traction.

Do you understand the issues surrounding citizenship in today’s world of increased migration and globalization? Do you know which countries disallow dual citizenship, or where citizenship rights are drawn along gendered lines?

Test yourself with this quiz, informed by The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship:

The quiz is also available online here.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Blank Map-World-noborders’ by E_Pluribus_Anthony*chris. CC0 Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The post The OUP citizenship quiz appeared first on OUPblog.

March 11, 2018

Sexuality and the Holocaust

When, at one point in 2008, Nancy Wingfield approached me with the idea that I should write a paper about prostitution in Theresienstadt, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. That was probably for the best, because before long, I was confronted with hostile, personal attacks from survivors, which demonstrated quite clearly how sensitive the topic was. It was no accident that Wingfield is a historian of sexuality rather than a Holocaust historian: as I found out, sexuality and the Holocaust, while a topic of immense public interest, is a field that makes people profoundly uncomfortable.

In 2016, Elissa Mailänder and I decided to address the intersection of sexuality and the Holocaust in a roundtable at the German Studies Association, which we later turned into a forum in German History with Doris Bergen, Atina Grossmann, and Patrick Farges. Our conversation took as a point of departure the Simon Watney’s statement, quoted in Dagmar Herzog’s History of Sexuality in Europe, about the “much of muchness” that sexuality bears. In sexuality, we can observe how society expresses and enforces its key cultural values; studying gender and sexuality gives us tools to examine the dynamics of unequal relationships and the stabilizing and destabilizing effects of intimacy. Illustrating the latter point, Bergen brought up the iconic moment in Gitta Sereny’s Into that Darkness, when it was Theresa Stangl’s providing of support and physical love that enabled her husband to carry on as commandant of two camps of Operation Reinhard.

To this day, when we speak about sexuality and the Holocaust, most will automatically zoom in on sexual violence against Jewish women. Thanks to the work of Herzog, Helga Amesberger, Regina Mühlhäuser, Birgit Beck, Robert Sommer, Monika Flaschka, and others, we are well informed about its prevalence, impact, and logic. In particular, Mühlhäuser’s study of both enforced and consensual relationships on the Eastern front set a high standard in theorizing and making sense of sexual violence. Today, sexual violence is an accepted part of study of the Holocaust, addressed in exhibitions as well as general Holocaust histories.

And yet, the implementation is frequently frustrating: often, sexual violence is employed to titillate the reader, or worse yet, as the clichéd “add women and stir.” Photographs of raped women are presented without any context, victims are mentioned as heaps of flesh, gang-raped in the last minutes of their lives. Elissa Mailänder showed how difficult, indeed impossible, it is to have empathy with people about whom all we learn about is that they were sexually assaulted, raising the key issue of historian’s ethics in writing about sexual violence.

“Studying gender and sexuality gives us tools to examine the dynamics of unequal relationships and the stabilizing and destabilizing effects of intimacy.”

These difficulties in addressing sexuality and gender stem from the fact that Holocaust studies still struggles with gender history being taken as a valid, central line of inquiry. To some collegues (usually men), there is still a notion of gender history as niche, of not being part of the “real questions” and “hard facts.” It is interesting, if sad, that some of this patriarchal bias repeats in queer history, which too often turns into gay men writing about gay men. A good example of the condescention towards the experience of lesbian women during Nazi Germany is the ongoing struggle to commemorate women persecuted as lesbians at Ravensbrück Memorial. Moreover, Samuel Huneke’s publicized recent article on lesbian women facing the Berlin Gestapo argued for “an unmistakable and thoroughgoing toleration of lesbianism in Nazi Berlin.” Huneke claimed to be the first one to work with these cases—disregarding the research by Ingeborg Boxhammer and Camille Fauroux . Boxhammer’s and Fauroux pioneering, painstakingly researched studies came to very different conclusions, demonstrating the manifold ways in which lesbians were endangered. Do we only take note of historical findings when presented by a male historian?

The key characteristic of queer history is in its innate subversivity: of reading sources against the grain, recognizing how the Holocaust changed gender norms, sometimes turning them upside down. In my work, I explore Jewish Holocaust victims who engaged in same sex desire, and the surrounding homophobia of the prisoner society. Cornelie Usborne works on the often exploitative relationships between German housewives and French forced workers and POWs, where the women coaxed the French into intimacy. Topics like these are steeped in stigma: understanding which sexual conduct generates shame and taboo is currently being heavily explored in research. Annette Timm’s edited collection on Ka-Tzetnik is a significant contribution to our understanding how postwar public sexualized the Holocaust. The work of the Czech American Holocaust survivor novelist Arnošt Lustig is waiting for a critical analysis.

When Marie Jalowicz Simon’s memoir of life in hiding came out, readers were captivated by her matter-of-factly depiction of bartering her survival for money, help, affection, and sex: recognizing that sex was a currency, and one currency among others, is key. Finally, and to come back to the beginning, historians of the Holocaust and Nazi Germany are still profoundly uncomfortable in analyzing prostitution beyond sexual violence. Only Zoe Waxman’s and Maren Röger’s books are two prominent recent examples. It is hard and sometimes confusing to recognize women’s agency in these usually enforced, violent situations. The subversive, explosive value of Jalowicz and Molly Applebaum’s accounts is that to a discerning reader, women’s choice, limited but legitimate, is there in plain light. With that, we can ask: what does it mean? Only then we can set out to understand the society brought about by the Holocaust.

Featured image credit: Birkenau-Auschwitz Concentration Camp by Ron Porter. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Sexuality and the Holocaust appeared first on OUPblog.

What is the future of the European Union?

The European Union (EU) is facing turbulent times. It is plagued by deep divisions over how to shape its future. Over half a century of integration has created a profound interconnectedness between the political, economic, and social fates of member states. At the same time, however, the fortunes of member states have started to diverge dramatically. The Eurozone crisis for example unmasked deep structural imbalances across the Union.

The political fault lines are widening. Today, they crosscut the continent from North to South on economy and austerity, and from East to West on migration and human rights. These developments have also left a mark on public opinion. Bruised by the Eurozone and refugee crises, large parts of the public have come to doubt the competence and integrity of their political and financial masters in Brussels and at home. Eurosceptic sentiment is on the rise. It is no longer a phenomenon tied to small segments of society, extremist political parties or specific economic cycles.

For a long time public opinion was viewed as largely irrelevant for the course of European integration. Elites could pursue further integrative steps with little regard for what the public wanted. Today, leaders in Brussels and Europe’s capitals are confronted with a new and challenging political reality: the unprecedented development of European governance has led to greater public contestation, yet at the same time the EU is more reliant on public support for its continued legitimacy than ever before.

What exactly do we mean by Eurosceptic public opinion? Is it the driver of recent Eurosceptic party success, or do national conditions and evaluations play a more important role? And finally, when does Eurosceptic public opinion have the ability to constrain the preferences of elites who shape jurisdictional choices in Europe? These are important questions for every student or observer of European politics.

Euroscepticism is not a stand-alone phenomenon. It is deeply rooted in and framed by people’s national experiences. Euroscepticism essentially boils down to a comparison between the benefits of the status quo of membership and those associated with the alternative state, one’s country being outside the EU. It takes shape in conversation with one’s national reference point, is there a viable alternative to membership? When people are more optimistic about their country’s ability to deliver, they become more Eurosceptic, and vice versa. This insight is important as it helps us understand why support for the EU remains relatively high in bailout-battered member states that have experienced some of the worst effects of the crisis, like Ireland or Spain, while Euroscepticism is on the rise in countries that have benefited enormously from the Single Market and/or the Euro, and weathered the crisis relatively well, such as Germany or the Netherlands. Yet, public opinion cannot be simply characterized as Eurosceptic or not. Rather it consists of different types. Distinguishing between these types is important as they translate into very different policy priorities, vote choices and preferences for EU reform.

The EU is more reliant on public support for its continued legitimacy than ever before.

Euroscepticism is such a diverse phenomenon precisely because the Eurozone and refugee crises have exacerbated structural imbalances within the EU and consequently made experiences with the Union more distinct than ever before. As the economic, political and social conditions of member states started to diverge further and further during the crisis, people’s national reference points also moved further apart.

The EU today is characterized by growing preference heterogeneity. There is an expanding rift between different types of sceptics within and across countries in terms of what they want from the EU. Some sceptics, especially within the North Western region, demand less intra-EU migration, while others, most notably in Southern and Central and Eastern European member states, wish to see more economic investment and employment programmes. This represents somewhat of a policy conundrum. Although it might be possible to strike a balance between these different demands by introducing some sort of transfer or debt reduction mechanism that would allow poorer economies to grow and thus depress the need for migration in the future, the fruits of such reforms would most likely only come to bear in the medium or long run. Given the importance of EU matters in domestic elections and for the re-election of national governments, current incumbents will most likely focus on their short-term political survival rather than medium- to long-term policy solutions.

So, how should the EU move forward? The growing preference heterogeneity suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach for addressing Euroscepticism is unlikely to be successful. One way for the EU to deal with different constituencies, might be to fully embrace the diversity within its borders and provide more differentiated and flexible policy solutions. Perhaps successful integration should not be defined as a form of harmonization or even homogenization, but rather be rooted in the principle of flexibility. A flexible rather than fixed end goal could prove a strong argument for the public to stick with the European project, even though it is fundamentally divided about what it wants from Europe.

Featured image credit: EU flags in front of the Berlaymont building, head office of the European Commission by Amio Cajander. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons .

The post What is the future of the European Union? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 10, 2018

Women in philosophy: A reading list

This March, in recognition of Women’s History Month, the OUP Philosophy team will be celebrating Women in Philosophy. The philosophy discipline has long been perceived as male-dominated, so we want to recognize some of the incredible female philosophers from the past including Simone de Beauvoir, Mary Wollstonecraft, and Hannah Arendt, plus female philosophers doing great things in 2018 like Martha Nussbaum, Clare Chambers, and Kate Manne.

Find these and more in our reading list below, highlighting recent works in the field of feminist philosophy and classic female philosophers. Visit our Women in Philosophy page for more book recommendations, along with free access to online products and journal articles focusing on female philosophers and feminist philosophy.

Women in Philosophy: What Needs to Change?, edited by Katrina Hutchison and Fiona Jenkins

Why are professional philosophers today still overwhelmingly male? Some assume that women need to change to fit existing institutions. Instead, this book offers concrete reflections on the ways in which philosophy needs to change to benefit from the important contribution that women’s full participation makes to the discipline.

Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, by Kate Manne

Down Girl is a broad, original, and far-ranging analysis of what misogyny really is, how it works, its purpose, and how to fight it. Kate Manne argues that misogyny should not be understood primarily in terms of the hatred or hostility some men feel toward women. Rather, it’s primarily about controlling, policing, punishing, and exiling the “bad” women who challenge male dominance. Down Girl examines recent and current events, showing how these events, among others, set the stage for the 2016 US presidential election.

The Social and Political Philosophy of Mary Wollstonecraft, edited by Sandrine Bergès and Alan Coffee

Bergès and Coffee bring together new essays from leading scholars exploring Mary Wollstonecraft’s moral and political philosophy, both taking a historical perspective and applying her thinking to current academic debates. Subjects include Wollstonecraft’s ideas on love and respect, on friendship and marriage, motherhood, property in the person, and virtue and the emotions, as well as the application for current thinking on relational autonomy, animal rights, and children’s rights.

Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher, by Edward J. Watts

Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher, by Edward J. Watts

Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher brings to life Hypatia’s intellectual and political triumphs, uncovers the unique challenges she faced as a female teacher in a man’s world, details the tragic story of her murder, and shows why her story has fascinated people for 1600 years.

Scarlet A: The Ethics, Law, and Politics of Ordinary Abortion, by Katie Watson

Twenty-one percent of American pregnancies end in abortion; although statistically common, and legal since 1973, abortion still bears significant stigma–a proverbial “scarlet A.” Fear of this stigma leads most of those involved to remain silent. This book brings abortion out of the shadows and invites a new conversation about its actual practice, ethics, politics, and law. Katie Watson lends her incisive legal and medical ethics expertise to navigate wisely and respectfully one of the most divisive topics of contemporary life.

Against Marriage: An Egalitarian Defense of the Marriage-Free State, by Clare Chambers

Against Marriage is a radical argument for the abolition of state-recognized marriage. Clare Chambers argues that state-recognized marriage violates both equality and liberty, even when expanded to include same-sex couples. Instead Chambers proposes the marriage-free state: an egalitarian state in which religious or secular marriages are permitted but have no legal status.

Diotima at the Barricades: French Feminists Read Plato, by Paul Allen Miller

Diotima at the Barricades argues that the debates that emerged from the burgeoning of feminist int ellectual life in post-modern France involved complex, structured, and reciprocal exchanges on the interpretation and position of Plato and other ancient texts in the western philosophical and literary tradition.

ellectual life in post-modern France involved complex, structured, and reciprocal exchanges on the interpretation and position of Plato and other ancient texts in the western philosophical and literary tradition.

Women and Liberty, 1600-1800: Philosophical Essays, edited by Jacqueline Broad and Karen Detlefsen

This volume offers a collective study of liberty as discussed by female philosophers, and as theorized with respect to women and their lives, in the 17th and 18th centuries. The contributors cover the metaphysics of free will, and freedom in women’s moral, personal, religious, and political lives. Women and Liberty, 1600-1800 brings attention to women’s neglected yet sophisticated contributions to numerous philosophical issues.

Featured image credit: Blue and Gold Cover Book by Negative Space. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Women in philosophy: A reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Ascending to the god’s-eye view of reality

Frank Wilczek famously wrote:

“A recurring theme in natural philosophy is the tension between the God’s-eye view of reality comprehended as a whole and the ant’s-eye view of human consciousness, which senses a succession of events in time. Since the days of Isaac Newton, the ant’s-eye view has dominated fundamental physics. We divide our description of the world into dynamical laws that, paradoxically, exist outside of time according to some, and initial conditions on which those laws act. The dynamical laws do not determine which initial conditions describe reality. That division has been enormously useful and successful pragmatically, but it leaves us far short of a full scientific account of the world as we know it. The account it gives—things are what they are because they were what they were—raises the question: Why were things that way and not any other? The God’s-eye view seems, in the light of relativity theory, to be far more natural … ascending from the ant’s-eye view to the God’s-eye view of physical reality is the most profound challenge for fundamental physics in the next 100 years.”

To explain “event X,” physicists generally start with events in the past of event X (initial conditions) that can be time-evolved via the laws of physics to give rise to event X. As Sean Carroll has pointed out, this use of initial conditions and dynamical laws to provide a time-evolved story is used throughout physics to include Maxwell’s equations of electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, special and general relativity, and quantum field theory. Appropriately, Lee Smolin has called this ant’s-eye explanation the “Newtonian Schema.”

The Newtonian Schema conforms well with our time-evolved perceptions (ant’s-eye view) since we remember the past and we want to predict the future. Mathematically, we can use our laws of physics in differential form to model this Newtonian Schema thinking. For example, consider a rock launched from a trebuchet (initial conditions) that subsequently smashes a castle parapet (event X). The rock’s trajectory would be a parabola according to Newton’s second law of motion, F = ma, i.e., force equals mass times acceleration. Gravity acting in the vertical direction supplies F for Newton’s second law in this case which results in a second-order differential equation in vertical position as a function of time (since acceleration is the second derivative of position with respect to time).

Image created by Michael Silberstein, W.M. Stuckey, and Timothy McDevitt. Used with permission.

Image created by Michael Silberstein, W.M. Stuckey, and Timothy McDevitt. Used with permission.

This second-order differential equation requires two pieces of information to render position as a function of time for the rock. If one chooses initial velocity and initial position, these two pieces of information would be called initial conditions. Choosing conditions at the beginning of the motion and asking what happens per the laws of physics reflects the fact that we remember the past, not the future, so in general, we want predictions, not retrodictions.

This ant’s-eye approach works well to provide explanation consistent with our time-evolved perception, i.e., “things are what they are because they were what they were,” but the ant’s-eye approach can leave us asking, “Why were things that way and not any other?” As long as we can account for the initial conditions, e.g., we built and loaded the trebuchet, our ant’s-eye explanation works well.

Unfortunately, there are situations in physics where the initial conditions are inexplicable, e.g., conditions at the Big Bang. In quantum mechanics, we have the delayed choice experiment where what we would expect to be the explanans (experimentalist’s choice of experimental configuration) occurs after what we would expect to be the explanandum (experimental outcome). In these cases, the ant’s-eye view of reality creates mystery; however, the God’s-eye view easily resolves the mysteries created by the ant’s-eye view.

In the mathematical formalism associated with the God’s-eye view, one casts the laws of physics in integral form rather than differential form using the “action.” The action is the integral of the Lagrangian (kinetic energy minus potential energy) from the beginning of the trajectory (where our rock is launched) to the end of the trajectory (where the parapet is smashed). The trajectory that makes the action minimal or maximal with respect to nearby trajectories is the trajectory that actually exists in spacetime. This is called the “principle of least action” and demanding that it be satisfied instant by instant gives rise to the differential form of our laws of physics (F = ma for our rock). Appropriately, this God’s-eye approach is what Huw Price and Ken Wharton call the “Lagrangian Schema.”

Per the God’s-eye view of reality:

“There is no dynamics within space-time itself: nothing ever moves therein; nothing happens; nothing changes. In particular, one does not think of particles as moving through space-time, or as following along their world-lines. Rather, particles are just in space-time, once and for all, and the world-line represents, all at once, the complete life history of the particle.” — Robert Geroch.

Since spacetime is “once and for all,” the Lagrangian Schema explanation of the events in spacetime needn’t be restricted to time-evolved storytelling compatible with our ant’s-eye experience. God’s-eye explanation resides in spatiotemporal patterns per “global constraints,” such as the principle of least action, whereby the goal is “spatiotemporal self-consistency.” Accordingly, the present needn’t be explained by the past alone; rather the past, present, and future co-explain each other in the God’s-eye view. Initial conditions that are inexplicable per the ant’s-eye view are now explicable and the requirement of strict causal ordering is dismissed as an unnecessary limitation created by our ant’s-eye bias.

As Ken Wharton points out,

“When examined critically, the Newtonian Schema Universe assumption is exactly the sort of anthropocentric argument that physicists usually shy away from. It’s basically the assumption that […] the computations we perform are the same computations performed by the universe, the idea that the universe is as ‘in the dark’ about the future as we are ourselves.”

Until we physicists can discard our self-imposed anthropocentric constraints resulting from our ant’s-eye bias, we will not rise to Wilczek’s challenge and ascend to the God’s-eye view of reality.

Featured image credit: ‘Tracked Milky Way’ by Adrian Pelletier. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Ascending to the god’s-eye view of reality appeared first on OUPblog.

All the president’s tweets

It seems long ago now, but in his victory speech in 2016, Donald Trump promised to unite us as a nation. He finally has, at least around one issue: nearly seven of every ten Americans wish he would stop tweeting from his personal account. According to a recent Quinnipiac poll, that even includes a majority of Republicans. Melania, who says that she abhors the negativity and bullying of social media, said on 60 Minutes that she rebukes her husband all the time for his tweets. But she accepts that in the end “he will do what he wants to do.”

Of course he will. Mr. Trump sees social media as a source of power, a way of fighting back. And his tweets reach an audience of 43 million, according to twitteraudit. Only half of them are real, but he still has about as many actual viewers as the ABC, CBS, and NBC evening news programs combined. That gives the president a formidable weapon, which he uses to lash out at the mainstream media and present his own version of “reality.” He ridicules his critics, praises his allies, and boasts of his accomplishments. Twitter lets him dominate news cycles, bypass the “failed” media and redirect journalists’ focus, all while stoking his base. And he can do it all very quickly, without impediments by fact-checkers.

But Twitter also may serve a more personal purpose for the president. He told Playboy in 1990 that he typically wakes up at four in the morning with “controlled neuroses,” which he described as a “tremendous energy level” and “an abundance of discontent.” Many of his early morning tweets today display that same restless energy and aggrieved discontent. The metadata of his Twitter account show that during the campaign and in the first months of his presidency, Mr. Trump sent many tweets between five and nine am, using an Android phone. One study found that his early morning tweets were angrier and more inflammatory than ones sent later in the day on an iPhone, presumably by his staff. He still sends nearly 40% of his daily tweets during those hours, especially while Fox and Friends is on the air.

Mr. Trump’s early morning tweets contain attacks like “The media is going crazy. They totally distort so many things on purpose” and conclude with exclamations like “FAKE NEWS!” The most common words in those tweets include “badly,” “crazy,” “weak,” and “dumb.”

If tweets are speech, the president has learned to speak Twitter as a second language.

Mr. Trump’s tweets are often impetuous, denigrating, and simple in substance and style. That makes Twitter the ideal instrument for him, says communications scholar Brian L. Ott. By its nature, Twitter fosters those very qualities, says Ott. It presents no barriers to instant publication and so lends itself to impulsivity. Its impersonality promotes incivility. And its 280-character limit doesn’t allow for complexity.

The linguist John McWhorter calls tweets “fingered speech”; more a form of casual speaking than of writing. Mr. Trump seems to get that instinctively. He tweets as if he’s talking straight to the individual reader, sometimes asking direct questions to create a sense of intimacy. He uses language everyone can understand. (One study showed that he prefers words at a third- or fourth-grade level.) He often tweets in sentence fragments. He capitalizes words for emphasis. And he’s masterful at concluding messages with fragmentary outbursts like “Very dishonest!” or “Sad!” That suits his goals perfectly, because people often retweet messages that are both emotional and morally judgmental.

Some observers argue that this style comes naturally to the president, since his tweets reproduce his public speaking habits. But to some extent the opposite is true. The syntax of Mr. Trump’s ad-libbed campaign speeches was often so self-interrupting and disjointed that transcribers couldn’t punctuate his sentences (so they used lots of em dashes). The linguist Geoffrey Pullum examined a very long passage in one of Mr. Trump’s speeches and found no sentence structure at all. In the president’s tweets, by contrast, the brief format seems to impose syntactic restraint. He‘s a long way from being “the Ernest Hemingway of 140 characters,” which he claims somebody said he is. But his sentence structure is often simple and clear.

In his punctuation, the president sometimes follows the common practice on social media of omitting commas where we would expect them, as in this tweet: “Do you think the three UCLA basketball players will say thank you President Trump?” He often uses comma splices where he should use periods, as in this unwittingly ironic tweet giving advice to the media: “Be nice, you will do much better.” But in many tweets he gets the commas right, showing that he knows the formal rules. And though he uses exclamation points a lot, he generally doesn’t write them in clusters, as is the frequent practice on social media. Nor does he deploy them simply to express sincerity or warmth, as many young people do in digital messages. Instead, he uses exclamation points in the traditional way: to show emphasis or strength, or to mark the imperative mood, as in “Do not worry!”

If tweets are speech, the president has learned to speak Twitter as a second language, though with a Standard English accent. And he uses its conventions to enormous effect. By his own admission, his style is often outrageous. But it’s far more deliberate than it may seem.

Featured image credit: Social media apps by Jason Howie. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post All the president’s tweets appeared first on OUPblog.

The illegal orchid trade and its implications for conservation

When most people think of illegal wildlife trade, the first images that spring to mind are likely to be African elephants killed for their ivory, rhino horns being smuggled for medicine, or huge seizures of pangolins. But there is another huge global wildlife trade that is often overlooked, despite it involving thousands of species that are often traded illegally and unsustainably. Orchids are perhaps best known for the over 1 billion mass-market pot plants traded internationally each year, but there is also a large-scale commercial trade of wild orchids for food, medicine and as ornamental plants. This is despite the fact that all species of orchids are listed by the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), which regulates and monitors the commercial trade of wild plants and animals that may be threatened by exploitation. Whilst CITES discussions often focus on elephants and other charismatic mammals, orchids make up over 70% of all of the species listed by the Convention.

Composition of the CITES Appendices, showing the large proportion of orchids within the species listed by the Convention Vector images courtesy of the Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

Composition of the CITES Appendices, showing the large proportion of orchids within the species listed by the Convention Vector images courtesy of the Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.To highlight the problems associated with the illegal and unsustainable orchid trade, a review paper was published in December 2017 by an international team of authors from the IUCN Orchid Specialist Group’s Global Trade Programme. This paper provides the first global overview of the orchid trade, drawing attention to not only its diversity but also the conservation problems associated with it. For example, the trade includes species traded as:

Medicinal orchids

Various different orchid species are used in traditional medicines in several countries and on a lot of different scales, including on a commercial level in some cases. For example, the stems and tubers of several species are used in Traditional Chinese Medicine, in products to improve general health condition as well as in medicines for specific problems. Similarly, South Asian Ayurvedic medicine uses at least 94 species of orchids in various medicinal preparations. In addition, orchids are used globally in various health products, including in bodybuilding supplements sold in Europe and the USA.

Edible orchids

Many people will have eaten orchids without realising, due to the countless products in international trade that contain the seeds of artificially propagated Vanilla orchids. However, this legal trade is only one example of orchids being used as ingredients in food and drink. One example is the trade in chikanda, a cake made from the ground tubers of terrestrial orchids and consumed in several countries in Central and East Africa. Another product made from the ground tubers of terrestrial species is salep, which is used as an ingredient in hot drinks and ice cream and consumed mainly in Turkey and neighbouring countries.

Ice cream made from orchids in Turkey. Photo credit: A Hinsley (Author).

Ice cream made from orchids in Turkey. Photo credit: A Hinsley (Author).Ornamental orchids

Orchids have been grown as ornamental plants for several thousand years, most commonly for their attractive flowers but also for their scent, patterned leaves or unusual growth habit. In Victorian Europe the ornamental trade was characterised by obsessive collectors suffering from orchidelirium (also known as orchid fever) that led them to pay huge sums for rare or unusual species. Whilst the majority of ornamental orchids traded internationally today are cut flowers and plants grown in greenhouses, there is still a large-scale commercial trade in wild, often illegally-collected plants. Harvesting for illegal trade is a particular problem in Southeast Asia, where species such as Canh’s slipper orchid (Paphiopedilum canhii) have been driven to extinction due to collection for international trade.

Whilst diverse, all of these trades have been linked to over-harvesting, causing decline and loss of species from the wild. In addition, the nature of the trade presents significant challenges to conservationists trying to regulate and monitor the trade. These include the direct threat from many different types of illegal harvest and trade, rapidly shifting patterns of consumer and supplier behaviour, the huge number of orchid species in trade that make identification difficult, and the fact that very little is known about the ecology of traded species, or how threatened they are in the wild. Finally, whilst the illegal trade in animals may get a lot of attention from the public, from conservation organisations and from policy makers, plants are often not seen as a priority, resulting in little funding being devoted to research or action to address the unsustainable trade

To address these challenges, the authors of the paper recommend that the conservation community should focus on conducting further research on trade dynamics and the impacts of collection for trade; strengthening the legal trade of orchids whilst developing and adopting measures to reduce illegal trade; and raising the profile of orchid trade among policy makers, conservationists and the public.

Featured image credit: Orchid by manfredrichter via Pixabay .

The post The illegal orchid trade and its implications for conservation appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers