Oxford University Press's Blog, page 269

March 20, 2018

The forgotten history of free trade: the Medici dynasty and Livorno

The Medici had everything, almost. They got immensely rich as bankers during the fifteenth century. As patrons of the arts they assembled some of the finest collections in Italy. They placed two scions on the papal throne as Leo X and Clement VII. They won political control over the city of Florence—first as informal rulers and, after 1530, as hereditary dukes. The Medici lacked only one thing to render their earthly felicity complete: they lacked a port city.

The Medici dynasty had big ambitions for their little state, and they turned to the malaria-ridden village of Livorno to realize them. The alchemically-inclined Francesco I (r. 1574-87) began the process of planning a new port in Livorno. His brother Ferdinando I (r. 1587-1609) put aside his cardinal’s cap to take up the grand duchy when Francesco died, perhaps by poison. It was Ferdinando who turned Livorno into “one of the most famous places for trade in all Christendom,” as one English merchant put it.

But, what did a Mediterranean port city mean during the long seventeenth century?

In an earlier age, commercial powers such as Venice had tried to control trade, with violence if necessary; they sought to capture commerce for their own ports and deny their rivals access to the richest routes. But such designs were increasingly out of place by the sixteenth century. The expansion of global trade and the entrée of new powers such as the Dutch and the English made the pursuit of monopoly in the Mediterranean a fruitless endeavor. A program of hospitality toward people and goods was a more profitable avenue for commercial expansion.

Ferdinando I de’ Medici. Uffizi Gallery by Polo Museale Fiorentino. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ferdinando I de’ Medici. Uffizi Gallery by Polo Museale Fiorentino. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In 1591, Grand Duke Ferdinando invited foreign merchants of any religion or nationality to settle in his port of Livorno. There they would enjoy security of person, property, and conscience—unlike elsewhere in Europe, where rulers enforced religious orthodoxy throughout their territories, and happily seized the assets of merchants when it suited their interests. Such policies earned Livorno a reputation as “a continuous fair of foreigners,” recalling the freewheeling fairs of the Middle Ages.

The Medici grand dukes also relaxed rules governing goods. In most cities during the Middle Ages, wares were subject to high taxes and a welter of bureaucratic controls—international trade occurred under strict supervision. By contrast, merchants in Livorno enjoyed a package of incentives for the warehousing, transit, and exchange of their wares. These measures culminated in a decree in 1676 that eliminated import/export dues entirely. The 1676 reform instantiated the principle that trade was to be taxed only for the provision of commercial services; that is, only to defray the cost of infrastructure such as harbor and warehouse facilities. “You know exactly what you have to pay, you pay it, and you’re done,” wrote one admirer,” without those annoying inspections that one so often finds in other places.”

Its provisions for hospitality toward merchants and goods made Livorno into Europe’s earliest and greatest free port. The low costs of doing business in Livorno put it at the center of long-distance commerce in the Mediterranean; it became the key entrepôt between northwestern Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Livorno exerted a powerful model in the region and beyond. By 1730 virtually all Italian ports were free ports of some kind, and they also spread to the Baltic and the Caribbean isles.

Free ports lowered ethno-religious and fiscal barriers to trade. They constituted surprising pockets of free trade in a commercial landscape dominated, at least in theory, by mercantilist restrictions on the movement of people and commodities. The reality was much messier than mercantilist fantasy envisioned.

Enlightenment economists were eager to enlist the free port into their arguments about the virtues of free trade. Adam Smith for one believed that “Brittain should by all means be made a free port, that there should be no interruptions of any kind made to foreign trade, that … all duties, customs, and excise should be abolished, and that free commerce and liberty of exchange should be allowed with all nations and for all things.” But free trade in a port city turned out to be something of a different beast than free port for the nation, and the free port dropped out of liberal discourse in the early nineteenth century.

Montesquieu dubbed Livorno “the policy masterpiece of the Medici,” punning on the dynasty’s fame as patrons of the arts. Like any masterpiece, Livorno’s influence is felt both everywhere and nowhere. It is in the principle of taxation solely for commercial services and in the conviction that restrictions on trade ought to be reduced to the bare minimum consistent with national security. And it is present in a more sinister mode in the modern special economic zone, where capitalism reigns untrammeled from social and environmental considerations. The grand duke of Tuscany believed that Livorno was “the key of my states”: and it is also one of the keys to that ambivalent world we call modernity.

Featured image credit: Castello del Boccale, Livorno by Etienne (Li). CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The forgotten history of free trade: the Medici dynasty and Livorno appeared first on OUPblog.

How did the plague impact health regulation?

What do we think of when we hear the word “plague”? Red crosses on boarded-up doors? Deserted medieval villages? Or maybe the horror film-esque cloak and mask of a plague doctor?

Unsurprisingly, the history of plague and its impact on health regulation is more complex and far-reaching than many assume. This extract from the Textbook of Global Health looks at the medical and environmental legacy of pandemics, which range from the Plague of Justinian, to the infamous Black Death and beyond.

For the most part, scientific ideas, technologies, and practices in medieval Europe trailed those of other societies, particularly in the Islamic world, where influential advances were made in such areas as astronomy, surgery, theories of disease-transmission, mind-body connections, and medical institutions. European healing involved a combination of local wisdom (e.g., knowledge of medicinal herbs passed down from generation to generation and among lay practitioners, including midwives who apprenticed with other wise women) and a hierarchy of town-based practitioners, such as apothecaries, barber-surgeons, and university-trained physicians.

It was during the Middle Ages that hospitals and religious orders dedicated to healing were established in Europe, partly to care for crusaders returning from Church-sanctioned military campaigns to recapture Palestine from Muslim control. Some institutions, such as St. Bartholomew’s in London, founded in 1123, still function today, as does Santa Maria Nuova in Florence. From about the 13th century on, secular hospitals were also founded in many larger European cities, though there was continued importance of the complementary role of the healing of the body and the healing of the soul.

Other changes were afoot that would test sanitary localism and Europe’s backwardness. As rival leaders fought for land and power (needing ever greater resources for these exploits), and merchants became interested in the riches and resources of faraway places, travel and commerce gradually increased, with microbes as companions. The congested towns of late medieval Europe were typified by poor sanitation and hygiene in comparison to some contemporary civilizations elsewhere, such as the Aztec Empire, and thus became loci of epidemic disease.

A physician wearing a 17th century plague preventive. CC-BY-4.0 via Wellcome Collection.

A physician wearing a 17th century plague preventive. CC-BY-4.0 via Wellcome Collection.Plague is among the earliest documented pandemics, with two great outbreaks bracketing the Middle Ages. The first, known as the Plague of Justinian, struck in 542 CE, decimating populations throughout Eurasia. The second pandemic began with the Black Death in 1347 and lasted until the late 17th century. It was the most destructive epidemic in the history of humankind, which resulted in an estimated 100 million deaths (almost one quarter of the world’s population, especially striking Asia, Europe, and the Middle East).

Surmised to have originated in wild rodents (probably in Central Asia), whose habitats were disrupted by a mix of human invasion, expansion of farming lands, and new trading patterns, what became known as the Black Death traveled by land and water along the Silk Road. It reached the Black Sea in 1346. By 1348 it had spread northward to Russia, westward to Europe, eastward toward China, and south-westward to the Middle East.

Although its cause was unknown, plague’s suspected communicability led to the earliest attempts at international disease control. In 1348, believing that plague was introduced via ships, the city-state of Venice adopted a 40-day detention period for entering vessels (a policy soon copied by Genoa, Marseille, and other major ports) after which the disease was believed to remit. This practice of quarantine—from the Italian word for forty—was minimally effective in stopping plague. Quarantine’s stricter counterpart, the cordon sanitaire—a protective geographic belt barring exit of people or goods from cities or entire regions—would also be used frequently in succeeding centuries. In 1423 Venice established the first lazaretto, a quarantine station to hold and disinfect humans and cargo. Its island location was emulated by other cities across the world.

Because the Black Death’s initial appearance preceded the formation of nation-states, sanitary efforts in the 14th century were adopted and implemented by municipal authorities with little coordination. While word of disease spread through travelers, initially there was no official system of notification or cooperation between city-states. However, by the 15th century many Italian towns and cities established plague boards, sometimes made into permanent public health boards, charged with imposing the necessary measures at times of outbreak. This precursor to international health authority, though local, rapidly developed a cooperative dimension through frequent correspondence between the plague boards.

Portrait of Girolamo Fragastoro. CC-BY-4.0 via Wellcome Collection.

Portrait of Girolamo Fragastoro. CC-BY-4.0 via Wellcome Collection.Over time, new ideas evolved around plague’s communicability, justifying ever-stricter quarantine measures. In 1546, the Veronese physician-scholar Girolamo Fracastoro revived ancient notions of contagion in his tract on plague transmission, theorizing that “seeds of disease” could be spread either through direct contact or by dissemination into the atmosphere.

Though the virulence of plague lessened somewhat in the 15th century, subsequent visitations worsened. In 1630–1631, plague killed one quarter of the population in Bologna, one third in Venice, almost half in Milan, and almost two-thirds in Verona. A scant generation later, half of the inhabitants of Rome, Naples, and Genoa succumbed to the plague of 1656–1657.

Plague, of course, was not the only deadly or epidemic ailment of the Middle Ages and early modern period. Smallpox, diphtheria, measles, influenza, tuberculosis, scabies, erysipelas, anthrax, trachoma, leprosy, and nutritional deficiencies were also rife. Less familiar today, mass hysteria in a climate of superstition led to outbreaks of dancing mania (St. Vitus Dance). Ergotism, arising from fungal contamination of rye, killed or disabled large numbers of people in dozens of epidemics between the 9th and 15th centuries.

Spurred on by more stringent sanitary enforcement during plague years, concepts of cleanliness and sanitation gradually took hold in Europe’s cities. Through increasingly forceful legislation and public awareness, announced via the printing press (c. 1440) and town criers, urban centers began to approach the hygienic standards reached by the Roman Empire more than a millennium earlier. Influenced by neo-Hippocratic ideas on the link between health and ‘airs, waters and places,’ health boards and many local governments took on more rigorous control of street cleaning, disposal of dead bodies and carcasses, public baths, and water maintenance. By the 18th century, cities began to employ, fitfully, a new environmental engineering approach to epidemic disease, which emphasized preventive actions including improved ventilation, drainage of stagnant water, street cleaning, reinternment, cleaner wells, fumigation, and the burial of garbage.

Even before the plague fully retreated, a new economic system began to develop that would irrevocably shape worldwide patterns of disease and eventually lead to international health measures and institutions.

Featured image credit: A street during the plague in London with a death cart and mourners by Edmund Evans. CC-BY-4.0 via Wellcome Collection .

The post How did the plague impact health regulation? appeared first on OUPblog.

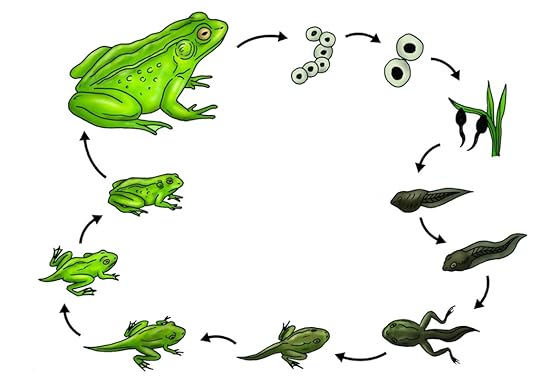

The science behind the frog life cycle [interactive guide]

Most of us remember learning the life cycle of a frog when we were young children, being fascinated by foamy masses of frogspawn, and about how those little black specks would soon be sprouting legs. That was a while ago, though. We think it’s about time that we sat you down for a grown-ups’ lesson on the life cycle of a frog.

Frog eggs face a plethora of challenges from the moment they are laid. Eggs laid openly in water are subject to desiccation if the water level drops, and are in danger of being eaten by fish and various aquatic insects. Several species have adapted to these challenges by depositing their eggs on vegetation above water, or in or above water in tree holes. These new-borns face challenges too however, as upon hatching many of these tadpoles must drop into the water below in order to complete their development. This is only the beginning of their journey to adulthood, however, as these eggs will soon develop into tadpoles, before metamorphosing into adults.

Click on each stage of the frog’s life cycle in order to learn some of the science behind one of nature’s most fascinating transformations.

Thinglink background image: Frog life cycle by Siyavula Education. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Thinglink background image: Frog life cycle by Siyavula Education. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Featured image credit: ‘Perereca-macaco – Phyllomedusa rohdei’ by Renato Augusto Martins. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The science behind the frog life cycle [interactive guide] appeared first on OUPblog.

Arranging The Lark Ascending for small string ensembles

I discovered the violin and piano version of The Lark Ascending in my youth, and I still remember how much I loved playing the violin part, unaccompanied. I was impressed by the programmatic transformation of the underlying poem as well as the liberating setting of the pentatonic scale and transcendent cadenza. Even then, I was already thinking of adapting this wonderful work for a different instrumentation.

Nowadays, The Lark Ascending is one of the most important and best-known compositions of Ralph Vaughan Williams (12 October 1872 – 26 August 1958). Originally composed for violin and piano in 1914, the work was inspired by a poem of George Meredith, a hymn to the song of the skylark written in 1881. In 1920, Vaughan Williams adapted his piece for violin and orchestra. This version was premiered in 1921, and today is one of the most popular classical pieces worldwide.

My personal goal when arranging other composers’ works is to achieve a strict authenticity. It´s an arranger’s main challenge. Every composer possesses a unique idiosyncrasy of style, instrumentation, and structure. In my opinion these individualities must be completely understood before starting an arrangement. Therefore, the first step here was to structurally compare the original version for violin and piano with the later version for violin and orchestra. Interestingly, Vaughan Williams created a piano part that translates very naturally into string writing. He used full-sounding wider intervals for the bassline and put the higher music lines into the corresponding overtone range, making the sound generally richer. He used the same principles when creating his orchestral version, adding wind instruments to expand the acoustic colour without changing the overall effect.

So how does one adapt an arrangement of a full orchestral score for just four or six strings? The answer is: to analyse the shape and structure of the main musical idea and try to re-compose the work in the composer’s own style — as if he himself had originally composed it for string quartet or string sextet. That means bringing the characteristic sounds of those instruments into focus by carefully adapting the original score.

Figure 20 from The Lark Ascending score for string quartet – triangle effect. Used with permission.

Figure 20 from The Lark Ascending score for string quartet – triangle effect. Used with permission. When arranging an orchestral work, the most difficult task is to convince the audience that all the original music lines have been included, even though some material has been intentionally omitted. Sometimes this is necessary to ensure that the new instrumentation creates the right effect without losing the authenticity of the original. To achieve that, however, subtle additions can be needed. These must always be structurally derived from the analysis of Vaughan Williams’s own orchestration principles.

To give a descriptive example: there is a section of trills of the solo violin in the middle part of the composition accompanied by a triangle (Allegro tranquillo, figure 20). Often percussion instruments are just omitted in arrangements, especially when they are unpitched like the triangle. But in this special case the triangle has a significant meaning within that music sequence. It’s an important rhythmical marker that represents a concluding off-beat contrasting with the trills of the solo violin. Every listener who knows the orchestral version of The Lark Ascending remembers the triangle, at least subconsciously. The importance of the triangle becomes evident as soon as it’s omitted. It sounds as if something is missing. So how to translate the sound of a bright, unpitched percussion instrument into one played by a strictly tonal stringed instrument? I decided to imitate the course of the sound when a triangle is struck. Put simply, the sound is initially strong but short-lived, followed by a quiet high-pitched final sound. To represent the initial strike, I therefore combined a pizzicato harmonic on the cello with a high-pitched harmonic on one of the upper strings.

I think the unique aspect of both arrangements is the new balance between solo violin and accompanying strings. The reduced accompaniment allows a fresh focus on the subtle tone colours and phrasing of the solo violin and results in a new kind of performance never heard before.

I have always been an admirer of Vaughan Williams‘s music. Arranging The Lark Ascending has been a privilege which has allowed me to pay a small, humble tribute to Vaughan Williams’s extraordinary and beautiful composition.

Featured image credit: Instrument by musik-tonger. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Arranging The Lark Ascending for small string ensembles appeared first on OUPblog.

March 19, 2018

Nuclear warfare throughout history: World War II [timeline]

With the dropping of the atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki during the Second World War, the nature of military conflict was changed forever. The nuclear arms race that ensued between the United States and the Soviet Union escalated throughout the twentieth century, limited by “Deterrance,” a policy of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD). In the timeline below, we trace the evolution of nuclear warfare and the role it played in World War II, with content pulled from Armageddon and Paranoia: The Nuclear Confrontation since 1945.

Featured image credit: TrinityColorLargeRestored by Jack Aeby of the Special Engineering Detachment, Manhattan Project, Los Alamos, 1945. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons .

The post Nuclear warfare throughout history: World War II [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

To be a mother and a scientist

Years ago, while researching my book Women Scientists, I asked famous women scientists to name the greatest challenge in their life. Almost without exception, they noted the difficulty of adjusting their family obligations and their work. Chemist Rita Cornforth, wife and colleague of the Nobel laureate John W. Cornforth, said: “I found it easier to put chemistry out of my mind when I was at home than to put our children out of my mind when I was in the lab.” The famous MIT professor Mildred Dresselhaus, often called “the queen of carbon science,” complained that with four children, it was impossible to get to work before 8:30 a.m., but her supervisor wanted her to be at work by 8 a.m. “The people who were judging me were all bachelors.” Similar examples in my interviews abound. I am not unfamiliar with this issue myself, having been a practicing scientist and mother of two (now adult) children.

It bothered me that so few women make it to the top of their profession in most STEM fields, so I have worked to spotlight these women and to provide role models for those young women who are considering science as a profession for themselves, but who are apprehensive about the potential sacrifices they might have to make in their family lives. When I talked about the difficulties with the first female full professor of chemistry of the University of Tokyo, I asked her if she could wish for anything—like in a fairy tale—what it would be? She hesitated, but after clarifying that she could ask for anything, however outrageous, she revealed her dream of having a family to accompany her (most brilliant) career in science.

Most of my interviewees were young in the early and middle part of the 20th century, when it was not common for a woman to work. This meant that day-care facilities were almost unheard of, and families had to organize childcare for themselves. More recently, there has been an increasing awareness of the unacceptably small number of women in STEM fields. I have been following this and it saddens me to see how slow the improvement has been. This is in spite of the fact that there are more and more initiatives trying to change the situation. The European Union publishes data on different aspects of women in STEM fields; there is a thick booklet every third year, titled “She figures.” The latest set of data, She Figures 2015, shows that the number of women going from the undergraduate to the PhD level has slowly increased, from 31percent to 37 percent. Then, there is a strong decrease, gradually becoming steeper through the assistant, associate, and full professor level, which stood at 13percent. Significantly, the curve starts to drop exactly at the time when PhD women are getting a job and start having children. The numbers did not improve more than just a few percentage points during the past decade or so.

“I found it easier to put chemistry out of my mind when I was at home than to put our children out of my mind when I was in the lab.”

Various countries try to alleviate the situation in different ways. In the USA, there is a project called ADVANCE, that’s main objective is to focus on work-family concerns. In the European Union, there is the TRIGGER project with similar objectives and approach. The Horizon 2020 program is the biggest program ever in the EU for research and innovation, with special emphasis on gender equality, although the work-family concerns are not explicitly stated there. Another current program is EFFORTI, a program for promoting gender equality in R&D. The programs seem to be elaborate and complicated, and for me it is not clear how progress will be measured.

There are different ways to ease the lives of women who have to cope with the double pressure of family and work. Institutional day care centers are among the most important incentives, both because they provide high-quality care and the children stay close to their parents. The possibility of flexible working hours as well as the option to take work home may further lighten the burden of reconciling the two competing timetables. For a certain period, allowing the mother to work part-time is another possibility. A few years ago, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences introduced an equal opportunity program for young women with children. This allows them to work on their higher doctorates two years longer than otherwise possible, and they might have other flexible arrangements as well. These are just a few of the approaches to bring young women scientists closer to “equal opportunity” in academia.

Some of my interviewees told me how their children reacted to their parents being scientists, for example to their talking about work at the dinner table. Some hated it, but there were others who felt proud. Their friends even envied them for getting to have interesting conversations at dinner. There were children, who experiencing how their parents loved what they did for a living, could not imagine other jobs for themselves than becoming scientists.

Featured image: Laboratory by jarmoluk. Public domain via Pixabay .

The post To be a mother and a scientist appeared first on OUPblog.

A visual history of the New York Crystal Palace [slideshow]

When New York’s Crystal Palace opened its doors in 1853, it quickly became one of the most endeared and celebrated landmarks in the city’s history. But five years later, the building was completely gone—engulfed in flames and reduced to a heap of smoldering debris. The following slideshow of photographs from The Finest Building in America recapture the sensation and spectacle behind the New York Crystal Palace: a building that mattered so much to antebellum Americans and New Yorkers, yet was never rebuilt.

Designs for the Crystal Palace: Sir Joseph Paxton

In the summer of 1852, the Association sponsored a competition for the design of a glass and iron building to rival the original Crystal Palace. The committee disqualified a plan sent in from London by Joseph Paxton himself because its elongated shape was wrong for the planned location in Reservoir Square. Paxton’s plan for the Crystal Palace in New York envisioned a structure 600 feet long and 200 feet wide but similar in appearance and construction to its Hyde Park counterpart. A London paper observed, “The design is, on the whole, remarkable for its simplicity and practicability, and is another proof of Sir Joseph Paxton’s great skill in this department of art.”

Image courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.

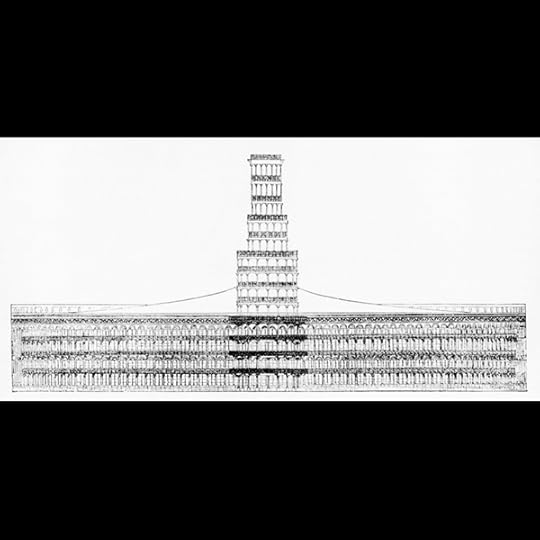

Designs for the Crystal Palace: James Bogardus

James Bogardus, a New York contractor who had already started to build with iron, sent in a plan for a circular building with a suspension roof that resembled the Roman Coliseum. Its base consisted of a huge circular hall, 400 feet in diameter, ringed by a four-story self-supporting cast-iron exterior wall. At its center was a thirteen-story, 300-foot-high cast-iron circular tower, inside of which was a steam-powered elevator that would carry visitors up to an observatory at the top. Linked chains from the tower supported the sheet-iron roof of the hall. Scientific American campaigned hard for Bogardus, claiming that his design was “superior in all its details to the London Crystal Palace. . . . It is so planned that none of the braces and binders, which so disfigured the interior of Paxton’s great work, will be required; it will be simple, yet beautiful and grand—a design original and unique, one worthy of our country . . . and it will never leak.”

Image courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.

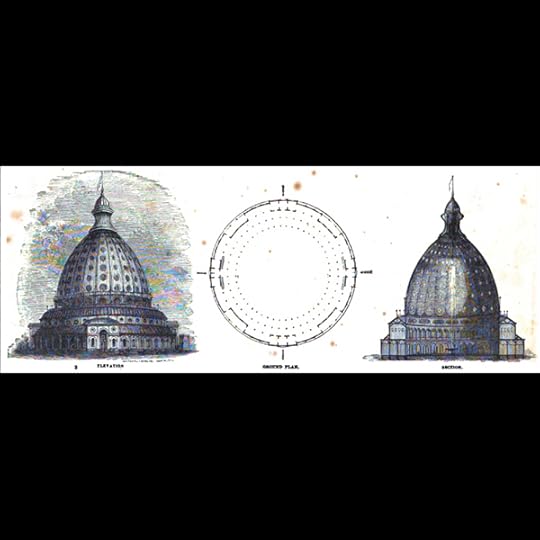

Designs for the Crystal Palace: Andrew Jackson Downing

A plan by Andrew Jackson Downing (submitted just prior to his death in a steamboat explosion), failed to pass muster because it used too much wood and canvas and not enough glass and iron, as stipulated by the city. Pictured above is Downing’s vision of a Crystal Palace for New York—a design “of great novelty and bold conception,” even though the dome was constructed of wood and canvas.

Image courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.

Designs for the Crystal Palace: Carstensen and Gildemeister

In August 1852 the committee chose a proposal from Georg Carstensen and his partner Karl Gildemeister. Carstensen reasoned, if the New York Crystal Palace were to be compared favorably with its London counterpart, it must rely on “the charms of novelty and originality, and thus escape the stigmatizing ridicule of being a miniature imitation of something much superior.” Pictured is a section of the original design, adopted in 1852. Note the grand staircases leading from the first floor to the basement, the large central fountain, and the entrance next to the Croton Reservoir on the right-hand side—none of which was ever built.

Image courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.

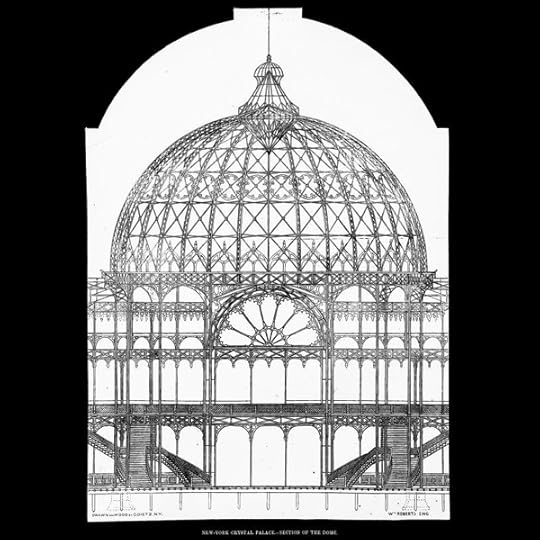

Carstensen and Gildemeister: the central dome

Recognizing the shortcomings of Reservoir Square, Carstensen and Gildemeister proposed an octagonal iron and glass building “mostly on the Venetian style” but in the form of a Greek cross capped by a central dome section showing the bracing and, on top, the lantern or cupola. “To our untravelled countrymen it may be a instructive example of the beauty and fine architectural effect of which this structure is capable.”

Image courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.

Carstensen and Gildemeister: foundation and interior

Because the square sloped down from east to west, they would first have to construct a two-foot-wide stone foundation wall that rose from ground level near the Reservoir to just over seven feet in height on the Sixth Avenue side of the Square. This foundation, plus freestanding interior piers of brick and stone, supported the floor joists as well as 190 slender cast-iron columns bolted to heavy baseplates. As in Paxton’s Crystal Palace, the exterior columns were cast hollow to carry rainwater from the roof. Pictured are the prefabricated cast-iron panels that formed the walls of the New York Crystal Palace.

Image courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.

The Latting Observatory

The Latting Observatory, the brainchild of a local inventor/hustler named Waring Latting, began construction directly opposite the Crystal Palace in March of 1853. It had dawned on Latting that he could make money by charging people to climb hundreds of feet for a panoramic view of the city below, plus suburban towns and villages in New Jersey, Westchester, Queens, and Brooklyn. Pictured is the Latting Observatory, with the 42nd Street entrance to the Crystal Palace on the far right.

The Latting Observatory, the brainchild of a local inventor/hustler named Waring Latting, began construction directly opposite the Crystal Palace in March of 1853. It had dawned on Latting that he could make money by charging people to climb hundreds of feet for a panoramic view of the city below, plus suburban towns and villages in New Jersey, Westchester, Queens, and Brooklyn. Pictured is the Latting Observatory, with the 42nd Street entrance to the Crystal Palace on the far right.

Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The Crystal Palace and gas lamps

It was often pointed out that the Crystal Palace eventually boasted almost as many gas lamps as the rest of the city combined. When the lights were turned on, the effect was magical. Said Putnam’s with eerie prescience: “if the roof of the Palace were all of glass, the space it occupies would, at night, look from a distance, like a conflagration.”

Image courtesy of Columbia University Libraries.

The Atlantic Cable

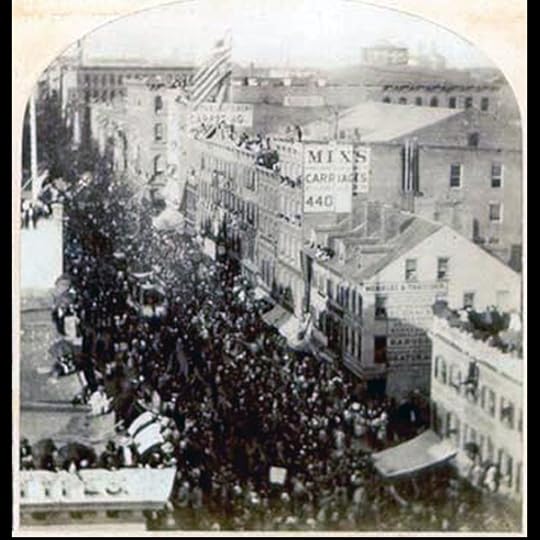

By 1858 the Crystal Palace remained standing on Reservoir Square, forlorn and slowly falling apart for lack of proper maintenance. On September 1, 1858, it was pressed into service as the northern terminus of a huge procession celebrating completion of the Atlantic Cable between England and America. “Cable fever runs wild” in New York, wrote the Times, describing hotels overflowing with guests and sidewalks thronged with excited visitors from town. Those people with tickets filed into the Crystal Palace for entertainments and speeches extolling the cable as well as the wondrous benefits it would bring. No American city has ever witnessed a more “picturesque display,” boasted the Times. They said it was “the greatest event of the age.”

Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Destruction of the Crystal Palace

On 5 October, the Crystal Palace burned to the ground. Lithographers and engravers tried to convey the magnitude of the disaster with scenes of billowing smoke and raging flames and crowds of onlookers rushing back and forth. Overshadowed by the back and forth over whether or not an arsonist caused the 1858 fire is the more arresting question of whether the Crystal Palace was prudently or competently built to begin with. Early in 1853, drawing attention to repeated delays, Scientific American had reprinted an article from the New-York Sun alleging that “The engineers and architects are at loggerheads; much of the material has to be fitted after it reaches the ground, beams being found too long, and girders too short.”

Pictured is a tribute of the Crystal Palace fire by Currier & Ives—the view from Sixth Avenue. Just before the dome collapsed, the flames burned through the halyard attaching a large American flag to the cupola. Along with panels of tin from the roof, the flag floated off into the sunset.

Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Featured image credit: “Burning of the New York Crystal Palace, on Tuesday Oct. 5th, 1858. During its occupation for the annual fair of the American Institute” scanned by the New York Public Library (Image ID: 1659236). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A visual history of the New York Crystal Palace [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

March 18, 2018

How Trump is making China great again

Over the last year, scholars, pundits, and policymakers interested in China have rhetorically asked whether US President Donald Trump will make President Xi Jinping’s China “great again.” There is now mounting evidence that the answer to that question is “yes.” Since his inauguration, there are a number of ways in which Trump has contributed to China’s rise, and Xi Jinping’s tightening grip on power.

To begin with as we, and others have suggested elsewhere, Trump is making China great again by withdrawing from global responsibilities so that space is left for Xi’s China to step into. Trump’s ‘America First’ policy has involved announcements of withdrawal from international responsibilities and agreements, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), UNESCO, the Paris Agreement on climate change, and UN talks on migration. He has threatened to withdraw from the Iranian nuclear deal, a free-trade agreement with South Korea, and NAFTA.

At the same time, Xi’s China has pursued the opposite policy, investing in exactly the kinds of overseas initiatives that built America’s global influence, including foreign aid and investment, overseas security, and education. The ‘Belt and Road Initiative’ – China’s massive connectivity project and Xi’s flagship foreign policy – has fortuitously emerged in this newly opened space.

This new leadership is not simply a question of filling the gaps left by US withdrawal. Instead, the Belt and Road Initiative exemplifies a new Chinese bid for world leadership, where networked capitalism and the Chinese national unit fuse to reinforce Chinese government narratives which portray China as the new trailblazer of global capitalism—thus illustrating and justifying a new Sinocentric order in East Asia and beyond.

The Chinese Party-State has long sought to convince the world, and the Chinese population, that Chinese leadership offers the world a better and more harmonious alternative to American power politics. With Trump in power, that suggestion is beginning to look a lot more credible to a lot more people around the world. As was recently argued, the US-led liberal international order is in crisis under the Trump presidency, which has little room for soft power. In that space, Xi is actively suggesting that China provides ‘a new option for other countries.’

The Chinese Party-State has long sought to convince the world, and the Chinese population, that Chinese leadership offers the world a better and more harmonious alternative to American power politics.

In this way, Trump is contributing to making China great again by taking on the role of the “bad” and “selfish” hegemon that enables Chinese leaders to portray their country as the better alternative.

What we haven’t discussed is the extent to which Trump is simultaneously helping Xi’s nationalist project by recognising China and its leadership as not opposite, but the same. On numerous occasions, Trump has identified China as protectionist, nationalist, and self-serving, rather than as a champion of international democracy and win-win cooperation. The remarkable thing is that he has done so approvingly.

When Trump visited Beijing in November 2017, he provided Xi with a fantastic propaganda opportunity by repeatedly praising the supreme leader of the China Party-State. In an address to business leaders in Beijing, joined by Xi, he blamed the ‘unfair’ trade deficit between the two countries on previous US leaders, and suggested that taking advantage of others, as he implied China had, was a good thing:”After all, who can blame a country for being able to take advantage of another country for the benefit of its citizens? I give China great credit.”

When President Xi recently declared that he was seeking to abolish the limit on presidential terms in China (which he now has), Chinese and international media made much of Trump’s (apparently joking) comment on lifetime presidency, that “I think it’s great. Maybe we’ll want to give that a shot someday.” In China, such apparent endorsement from the US President will give a modest boost to Xi in this controversial move for increased power. Most of all, it will make clear that the US President will not present an obstacle to this move from one-Party rule to one-person rule.

Whether this endorsement of Xi’s power-grab leads to ultimate Chinese ‘greatness’ is of course questionable. There are ample reasons to think that this move may make China less stable, as opposed to more, in both the short and the long term. For now though, Trump has added to the ways in which he is supporting Chinese nationalism, expansionism, and assertiveness on the world stage.

Featured image credit: ‘President Donald J. Trump and First Lady Melania Trump, joined by President Xi Jinping and First Lady Peng Liyuan, applaud and thank the performers at a cultural performance at the Great Hall of the People, Thursday, November 9, 2017, following a State Dinner in their honor, in Beijing, People’s Republic of China’, by Andrea Hanks. CC-BY-3.0 via The White House .

The post How Trump is making China great again appeared first on OUPblog.

“Alas, poor YORICK!:” death and the comic novel

Tragedy provokes sorrow and concludes with downfall and death. Comedy elicits laughter and ends happily. Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy is one of the funniest novels of world literature. But does the work, overshadowed by death, end happily? Can death and comedy mix? “Everybody dies. If you are going to take that badly, you’re doing it wrong. So you have to take it as a joke.” The sentiments of the celebrated Spanish cartoonist Antonio Fraguas, Forges, who died on 22 February 2018, might echo those of Sterne, whose own death took place 250 years ago on 18 March 1768.

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759-67), is a rare comic novel that doesn’t shy away from death. Contemporaries recognized Parson Yorick, the novel’s benign country clergyman, as a fictionalized version of the Reverend Laurence Sterne himself. In Tristram Shandy, Yorick—who takes his name from the dead jester in Shakespeare’s most famous tragedy Hamlet—dies before the midway point of the first of Sterne’s nine volumes. His death is marked by Hamlet’s familiar words, “Alas, poor Yorick!” inscribed on a marble slab—and a black leaf that speaks eloquently of the mystery of what lies beyond the grave.

Yorick himself was resurrected. Enjoying the fame Tristram Shandy brought him, Sterne performed the role of the good-natured parson in London society—at least when he wasn’t “Shandying” it (as he often was). And Yorick survived his earlier demise to become the central figure of A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy, published on 27 February 1768, less than three weeks before Sterne’s death.

Classical literature kept tragedy and comedy well apart. In sixteenth-century Italy, Giraldi Cinthio introduced the idea of la tragedia di lieto fine or tragicomedy. Yet, however subdued their conclusions, tragi-comedies end well. In the eighteenth century, by contrast, Henry Fielding thought comedy and death should keep their distance. So, he asked, in the preface to Joseph Andrews: “What could exceed the absurdity of an author, who should write the Comedy of Nero, with the merry Incident of ripping up his Mother’s Belly?”

The eighteenth century wasn’t short on savage humour. Is there anything in English to equal Swift’s A Modest Proposal in this regard? Still, funny as that work is, in parts, it is hard to think of Swift’s saeva indignatio as comic fiction—even if the French surrealist André Breton used it to open his Anthologie de l’humour noir.

Sterne, however, plays with death throughout Tristram Shandy. After Yorick, we hear of the death of Tristram’s brother Bobby, his mother Elizabeth, and even the much-loved Uncle Toby. The Story of Le Fever is an extended and much admired sentimental rendering of the gallant soldier’s dying.

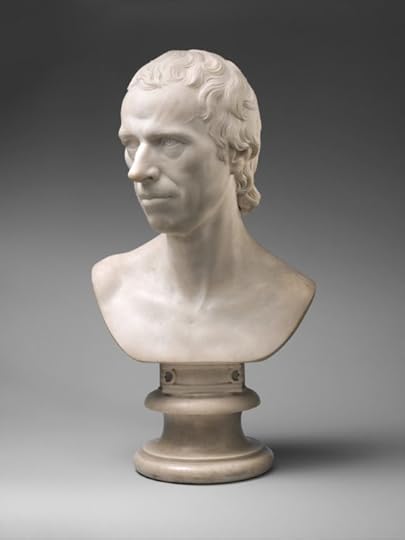

Joseph Nollekens (British, London 1737–1823 London) Laurence Sterne (1713–1768), first modeled 1765–66 British Marble; H. (with socle) 21-3/4 in. (55.2 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, John T. Dorrance Jr. Gift, in memory of Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll, 1979 (1979.275.2). CC0 1.0 Universal via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Joseph Nollekens (British, London 1737–1823 London) Laurence Sterne (1713–1768), first modeled 1765–66 British Marble; H. (with socle) 21-3/4 in. (55.2 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, John T. Dorrance Jr. Gift, in memory of Elinor Dorrance Ingersoll, 1979 (1979.275.2). CC0 1.0 Universal via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.The novel’s comic play with death is, however, anything but cynical—for Sterne himself had long suffered from pulmonary tuberculosis. In the first chapter of Volume VII, Death comes to call. The consumptive Tristram—another self-representation of the author—is buoyed up by his animal spirits:

DEATH himself knocked at my door____ye bad him come again; and in so gay a tone of careless indifference did ye do it, that he doubted of his commission_______

“There must certainly be some mistake in this matter,” quoth he.

Tristram intends to lead Death a dance, galloping, “without looking once behind me to the banks of the Garonne; and and if I hear him clattering at my heels______I’ll scamper away to mount Vesuvius … “(TS, VII, i). Sterne determined likewise, travelling rapidly south to the warmth of Naples. It was to little avail and the correspondence of his final years is punctuated by references to the inexorable progress of his illness.

Sterne’s response was to confront death by laughing at it, writing defiantly: “I brave evils et quand Je serai mort, on mettra mon nom dans le liste de ces Heros, qui sont Morts en plaisantant; [and when I am dead, my name will be placed in the list of those heroes who died in a jest].” His words recalled an allusion in Tristram Shandy to the Emperor Vespasian whose final words, Suetonius wrote, were: “If I am not mistaken I am going to be a god.”

Where else in fiction do we find so dogged a pursuit of comedy in the face of death? Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five is often very funny but the firebombing of Dresden—which the author experienced as a prisoner-of-war—has not persuaded many readers to consider it comic fiction. Terry Pratchett’s Mort, José Saramago’s As Intermitências da Morte, or George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo might suggest themselves but for most readers any list of comic novels about death is likely to be short.

Perhaps only Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 matches Tristram Shandy in suggesting fiction might be comic and deadly serious at the same time. As we eventually learn, Yossarian’s anguish results from his discovery of Snowden’s secret—around which the narrative circles obsessively—that “man [is] matter.” Sterne’s novel is always funny, its seriousness only occasionally overt:

Time wastes too fast, and every letter I trace tells me with what rapidity Life follows my pen; the days and hours of it, more precious, my dear Jenny! than the rubies about thy neck, are flying over our heads like light clouds of a windy day, never to return more_____every thing presses on …

_____Heaven have mercy on us both!

Yet true to the facetious tendencies that enliven Sterne’s writing, the following chapter is memorably short:

CHAPTER IX

NOW, for what the world thinks of that ejaculation_____I would not give a groat.

Is this, as F. R. Leavis once had it, “Irresponsible (and nasty) trifling”? Are death and comedy necessarily to be kept apart? In the British Independent, the obituarist Oliver Holmey wrote of Forges, that “To him, life was a comic strip, and so was death” (1 March 2018). Many years previously, a young Kenneth Tynan, making a name as the foremost drama critic of his day, asked rhetorically: “If tragedy is worth a death, why not comedy too?”

Why not?

Featured image credit: The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman by Laurence Sterne first London edition. Used with permission.

The post “Alas, poor YORICK!:” death and the comic novel appeared first on OUPblog.

Landmark moments for women in philosophy [timeline]

This March, the OUP Philosophy team are celebrating Women in Philosophy. Throughout time, women have had to fight for their place in history, academia, and the philosophy discipline. Women have made hugely significant contributions to both philosophy and academia as a whole and we believe it is crucial to look back at the landmark achievements of women in their work and recognize their importance.

To honour their contributions, we will be highlighting women and their achievements in the field of philosophy all throughout Women’s History Month.

Browse our interactive timeline of some of the most empowering moments in the history of women in philosophy. For more of our Women in Philosophy Month content, check out #WomenInPhilMonth on Twitter.

Which female achievements in academia would you add in? Let us know in the comments.

Featured image: Nine Living Muses of Great Britain by Richard Samuel. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Landmark moments for women in philosophy [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers