Michael Shapiro's Blog, page 7

August 8, 2016

Sweet home Chicago: Blues, baseball and barbecue, Inspirato, Summer 2015

Sometimes, if you’ve worked with an editor for a while, she approaches you with an assignment. And occasionally she opens the door to your dream story. When my editor at Inspirato suddenly had an opening for a feature and asked me to pitch a story about Chicago, I sent in essence a three-word reply: “Blues, baseball, barbecue.” Ultimately I got the assignment and wrote about my favorite aspects of the City of Big Shoulders.

Chicago is one of the country’s great cities for blues, baseball and BBQ.

Here’s the PDF, with plain text below: Chicago: Blues, baseball and barbecue

Sweet Home Chicago: Blues, baseball and barbecue

By Michael Shapiro

I worked hard, pretty damn hard, to get to Chicago for the first time. I was cycling across the country, from west to east, with a group raising funds for global hunger relief, and we didn’t have a day off between Salt Lake City and the Windy City. With each pedal push across Nebraska, Iowa and finally Illinois, Chicago – with its famed barbecue joints, soul-satisfying blues music, and the jewel that is Wrigley Field – I got a little closer.

The “City of Big Shoulders” as poet Carl Sandburg called Chicago, did not disappoint. As luck would have it, my hometown San Francisco Giants were in town to play the Cubs at Wrigley on July 17, 1986, and when a Cubs official heard we were riding across the country, (I think our police-escorted entrance into town made the local news), he promptly offered us free tickets above third base.

Walking to Wrigley for the first time made me feel like a kid with off-the-charts anticipation. There it all was: the big red sign out front reading “HOME OF CHICAGO CUBS,” the ivy-covered outfield walls, the classic green scoreboard with analog clock on top, and the buildings beyond the bleachers where people picnicking on rooftops watched the games for free.

“What makes Wrigley Field unique to me is the location. It’s a neighborhood ballpark that suddenly appears amid the brownstones,” says Carrie Muskat, author of Banks to Sandberg to Grace: Five Decades of Love and Frustration with the Chicago Cubs. “If you go to a game and have a sense of baseball history, Wrigley is even more special,” adds Muskat, who covers the Cubs for MLB.com. “Babe Ruth played there; Ernie Banks wanted to live there. And someday, the Cubs might win a World Series there.”

Wrigley Field has been showing its age, but that’s part of its charm, and a new Jumbotron installed this year adds 21st-century technology to the creaky yard. Mark Gonzales, who covers the Cubs for the Chicago Tribune notes that baseball is “deep-rooted” in Chicago and that loyalty is passed down through the generations. “You can always sell hope, and hope remains strong with the Cubs.”

That hope is captured in Norman Rockwell’s 1948 painting The Dugout. It focuses on a slump-shouldered bat boy with dejected Cubs players sitting in the dugout behind him. Above are several jeering fans, but there’s one smiling kid, thrilled just to be at the game. That’s the symbol of the true Cubs fan.

My 1986 visit to Wrigley was a day game, a couple of years before the ballpark installed lights. I soaked up sun and suds, cheering as my favorite pitcher, Vida Blue, hit a home run and pitched the Giants to victory. Welcome to Chicago.

A human-scale park (not a stadium) that holds about 40,000 people, Wrigley opened in 1914, and, astonishingly, the Cubs haven’t won a World Series in the century they’ve played there. Their last championship came in 1908. The closest they’ve come in recent years was in 2003 when they were five outs away from reaching the World Series. A fan interfered with a foul ball that may have been caught; then the floodgates opened. The Cubs lost that game and the next, ending their season.

Across town two years later, however, the Chicago White Sox won the World Series, and South Side fans, including an Illinois senator who’d be elected president in 2008, rejoiced.

* * *

Chicago knows how to celebrate. “This is possibly the last city in the world where you can see blues seven nights a week,” says Marc Lipkin, a spokesman for Alligator Records, a Chicago blues label. He ticks off the city’s famed blues clubs: Kingston Mines, B.L.U.E.S. on Halsted, Rosa’s Lounge, and Buddy Guy’s Legends, which opened in 1989. Guy typically plays a series of dates at his club in January. At other times of the year, if he’s not touring, Guy often joins whoever is on his stage for an impromptu jam. “To see Buddy at his own club is spectacular,” Lipkin says.

People in this traditionally blue-collar city have worked hard and danced into the wee hours at clubs featuring some of the best blues music in the country. It’s music that comes from the Deep South, songs meant to ease hardship and bring joy.

“When people from the South got to Chicago, they electrified,” says Ed Williams, a Chicago native and bluesman known as Lil Ed. “Electrified blues gave people a lot of feeling – that’s what made Chicago blues so special. And it was up-tempo too. The south blues was slow. In Chicago we started to put a little buff on it.”

Williams, the nephew of the late blues legend J.B. Hutto and front man for Lil Ed and the Blues Imperials, laughs easily and smiles often. “Musicians like to see people have fun, so blues is not all about just cryin’ and woo-woo-in’ and talkin’ about my baby’s gone, but a lot of blues is about gettin’ up and shakin’ your tailfeather,” he says. “Most people that’s got the blues, they’re looking for a way out. If you give them that way out through music, that helps them along because people don’t want to be miserable all the time, they want to be happy.”

In the 1930s and ’40s, when the acoustic Delta blues of Muddy Waters and Willie Dixon moved north to Chicago, the musicians plugged in “to compete with the volume level of the city,” says Alligator Records’ founder Bruce Iglauer. “You couldn’t play an acoustic guitar under the L tracks and expect to be heard.”

Iglauer calls Chicago blues the “toughest, hardest-edged, most visceral style of electric blues, because it grew out of the acoustic Delta blues sound which was the hardest, most rhythmic, most intense of the blues styles around the country. So Chicago, being a rough, tough city, nurtured a rough, tough blues sound.”

* * *

Billy Branch, a blues harmonica player who played with Willie Dixon in the late 1970s and early ’80s, believes most people don’t understand how much Chicago blues influenced rock music since its beginnings. He calls Dixon “one of the most influential musical composers of modern times,” but says that he’s not as well known as he should be. “You look at all these Led Zeppelin records and Rolling Stones songs, most of their early music was covers, including a few Willie Dixon songs. That’s not common knowledge to the general public.”

Branch hopes to spread awareness about Dixon’s contributions at this year’s Chicago Blues Festival (June 12-14), a free event held in Grant Park. “We are bringing back many of the musical players that are still around that played with Willie,” Branch said, but “that’s not a lot.”

Dixon and fellow blues legend Muddy Waters were born in 1915. The City of Chicago is honoring the centennial of their births at this year’s blues festival, says city spokeswoman Mary May. Some sources say Muddy Waters, whose real name is McKinley Morganfield, was born in 1913, but no definitive records exist. “Muddy said he was born in 1915 and that’s the date on his tombstone,” which is good enough for the city, May says.

Two of Muddy’s sons will be part of the tribute, she says, and Buddy Guy will headline the festival. The setting is ideal, she adds, with views of Chicago’s skyline and Lake Michigan. And because it’s free, some people who can’t go to blues clubs can enjoy the music.

Branch notes that Muddy Waters defined the Chicago blues sound in the mid-20th century, and that it’s this sound that so many rock bands sought to emulate. He recalls that Jagger and Richards named their band after Muddy’s song “Rollin’ Stone” and in 1981 came to Chicago’s Checkerboard Lounge to pay homage to him and serve as his backing band.

Gospel and soul singer Otis Clay, who like so many others journeyed to Chicago from the South as a youth, says blues isn’t the only roots music in Chicago. “When they talk of Chicago as being the blues capital of the world, it’s hard to say that without thinking of it as the gospel capital.” Clay says blues has borrowed heavily from gospel, the music of Southern churches. “You’ve got to follow that path from the South,” Clay said. “When they brought the blues in here, they brought the gospel as well.”

The transcendent gospel singer Mahalia Jackson came to fame in Chicago, Clay recalls. Chicago disk jockey and oral historian Studs Terkel was credited with “discovering” Mahalia because he played her records on his radio show, but he dismissed that, noting that she was filling black churches and concert halls in the city before most white people had heard of her.

Ultimately, Clay says, good music is good music, whether it’s soul, gospel or blues. “So when people start defining this music, it’s not an easy thing to do, I wouldn’t even try to do it. You know, if you like it, good.”

Alligator’s Lipkin says that even people who think they don’t like the blues change their minds when they come to Chicago. “When somebody says, ‘I don’t like blues’ and you put them in front of a live blues band, they will leave that club a blues fan. It almost never fails.”

* * *

The blues scene in Chicago has certainly changed since the days when Muddy and Dixon played to predominantly black audiences, and Buddy Guy and Junior Wells jammed at the now-defunct Theresa’s.

“I do feel something has been lost,” says Alligator Records founder Iglauer. “When I used to go to blues clubs on the south side or the Westside, the people in the audience and the people on the stage were basically the same people. They all shared a culture. Most had grown up in the South; they were working-class people, and they were sharing a style of music they have been listening to their whole lives. They had an ownership of the music. Even if they didn’t play it, it was their music.”

The scene has changed, but the muscular vitality of Chicago blues is as strong as ever, Iglauer adds. “Now the musicians are presenting the music to the audience, but luckily the best musicians put so much emotion into their performances that even if you didn’t grow up with the blues, which I certainly didn’t, you can feel the emotion coming off the stage. You can feel the honesty of the music.”

In sharp contrast to big arena shows, at blues halls you can get close to the performers. At B.L.U.E.S., “you can sit three feet from the stage,” Iglauer says. “At Kingston Mines you can sit 12 feet from the stage. At Legends, if you get a good table you can put your feet up on the stage. It’s music that is right there. The music is not showbiz; Chicago blues is the opposite of slick.”

Which is a fitting way to describe the barbecue and soul food that gives Chicago’s cuisine its distinctive flavor. This is down-home food, meant to satisfy hard-working people without breaking the bank.

Soul food and barbecue have been “hugely important in keeping Southern traditions alive,” says Adrian Miller, author of Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time. “What we understand as soul food is really the immigrant cuisine of the African-Americans who left the South. They did what any other immigrant group does: you land in a new place, and you try to re-create home.”

Otis Clay offers this advice for finding good soul food: “If it’s a soul food restaurant, it’s gotta have a woman’s first name.” The soul singer said he used to eat at Edna’s or Alice’s several times a week. Although their namesakes have passed on, Clay says, “sometimes I still go back; they left good recipes. They’re still going well.”

Miller agrees. “After eating my way through the country, I think Chicago has the best soul food scene outside of the South. What’s special about Chicago is that it’s a close approximation of what people were eating in the South.”

He also appreciates the barbecue options and says the city’s iconic dish is rib tips. Decades ago rib tips, which can be tough and chewy, were so unpopular that meatpackers would trash them or sell them for pennies per pound, so they became a staple for those with limited means. Today they’re a delicacy.

At Lem’s Bar-B-Q on the city’s South Side, manager Lynn Walker can spare only a minute to talk – she’s busy making sure the boisterous crowd that’s already arrived at the restaurant at 5 p.m. is getting fed.

What makes Lem’s ribs and tips so special? “It’s the sauce,” Walker says, “and the seasoning. They’re smoked, and you can feed your family with them.” Then Walker turns away to serve the next customer in the squat brick building with the big neon sign. Ribs and tips, because they’re not naturally tender, need to cook for a long time. But what once seemed like a curse turns out to be a blessing, as the slow cooking infuses the meat with smoky flavors.

Barbecue has come a long way from its roots as affordable meat. Carson’s, founded in 1977, elevated barbecue to fine dining “when no one else was doing that,” says Carson’s owner and operator Dean Carson. He says Chicago is a “great food town” especially for meat. “Everything went into Chicago alive, and everything left Chicago butchered to parts everywhere and unknown,” he says, recalling the town’s role in meat processing. “Chicago is a meaty town in all ways.”

And like all the best barbecue purveyors, Carson’s has a credo: “We stand firm in this: We do not boil or steam our ribs in any way; we do not bake them; we do not marinate them. We do not put a dry rub on them – those are euphemistic words for chemical tenderizer. End of story.”

Carson notes that ribs aren’t cheap anymore. You can pay as much for a plate of ribs as for a steak, but the lines out the door at his restaurant show many people are happy to spend the money.

I ask the owner to recommend his signature meal: “Cornbread, coleslaw, slab of ribs, au gratin potato,” all made on the premises, he says. When I ask about sauces, Carson stops me. “I got one sauce. I always think that if I go to a restaurant and they have eight different kinds of barbecue sauces that they don’t have one good one,” he says. The bill for this abundant feast is $25 and worth every penny.

* * *

With so many great chefs and bluesmen having passed, some may wonder if the traditions that have given Chicago such visceral vitality can live on. Muddy, Mahalia and Willie are long gone, yet traditions are being kept alive by Chicago stalwarts such as Lil Ed, Otis Clay and Buddy Guy, and so many others who learned from the masters.

Blues players and the people who put out their records are confident the music will endure because it keeps changing with the times. Lipkin, the spokesman at Alligator Records, notes that artists such as Lil Ed are “playing the blues the way it’s supposed to be played,” writing lyrics that are “meaningful now.” To this day, Lipkin adds, Chicago blues remains “a sound that will make the hair on the back of your neck stand up.”

Lil Ed himself remains optimistic about the future of Chicago blues: “A lot of people say that the blues might die away, but I think blues, all blues, will last forever,” he says with a smile. “You know why I say that? Because everybody has the blues, and the blues is going to be here all our lives. Even the young generation has got the blues. It’s something that will never go away.”

Then Lil Ed ends on a hopeful note. “You might be sad today, but the grass is always greener on the other side.”

— end —

BLUES CLUBS IN CHICAGO

Buddy Guy’s Legends

700 S. Wabash

(312) 427-1190

Chicago’s reigning blues kings brings top acts to his club and sometimes joins them on stage. The menu features Cajun-style soul food.

B.L.U.E.S.

2519 N. Halsted

(773) 528-1012

This intimate club focuses on Chicago blues icons including John Primer; locals get in free on Tuesday nights.

Kingston Mines

2548 N Halsted St.

(773) 477-4646

A Chicago tradition since 1968, Kingston Mines has two stages featuring continuous (but not simultaneous) music until 4 a.m.

Rosa’s Lounge

3420 W. Armitage Ave.

773-342-0452

rosaslounge.com

Opened by an Italian blues lover in 1984, Rosa’s carries on the tradition of classic blues lounges.

House of Blues

329 N. Dearborn, Chicago, IL 60654

312) 923-2000

National touring acts such as Gregg Allman and local blues musicians take the stage here. Their gospel brunch on Sundays features some of the city’s most talented singers.

—

BARBECUE AND SOUL-FOOD RESTAURANTS

Carson’s Ribs

612 N Wells

312-280-9200

Near Chicago’s Magnificent Mile, Carson’s offers generous plates of ribs at fair prices.

Lem’s Bar-B-Q

311 E 75th St,

(773) 994-2428

lemsque.com

For a taste of Chicago’s rib tips and other down-home fare, there’s no place like Lem’s, on the South Side.

Smoque

3800 N Pulaski Rd # 2,

(773) 545-7427

With perfectly smoked ribs, brisket and pulled pork, Smoque doesn’t rely on sauce for flavor.

County Barbeque, a DMK restaurant

1352 West Taylor St.

312.929.2528

dmkcountybarbeque.com

With craft spirits at the bar and rib tips on the menu, enjoy down-home food in an upscale setting.

Alice’s Restaurant

5461 W Division St.

(773) 921-1100

(no website)

One of the city’s historic soul-food eateries, Alice’s has kept the old recipes alive.

Guess who’s slicing your sturgeon, NYC’s ethnic food, Inspirato, Spring 2015

It’s no secret that many of the cooks making New York City’s best ethnic food didn’t grow up eating smoked salmon or corned beef sandwiches. On the upper east side I found two Chinese brothers selling fantastic sturgeon and the guys making the pastrami at Pastrami Queen on Lexington near 78th came from the Guatemalan pueblo of Solola. As an aside, it’s one of my favorite places there and when I told one of the chefs at Pastrami Queen that I’d been to his hometown he smiled as if to politely say “yeah, right.” Then I mentioned that Solola’s market days are Tuesday and Friday and that the village near Lake Atitlan is one of the few places in Guatemala where men still wear the traditional colorful clothing – his grin widened in recognition.

Immigrants Kenny and Danny Sze trained at Zabar’s and now run their own smoked-fish emporium on NYC’s upper east side.

—

Here’s the story in PDF form; from the Spring 2015 issue and in text below: Inspirato_Spring 2015_MS_NYC food

—

By Michael Shapiro

“There’s a lot to learn and the world is getting smaller,” says renowned chef David Bouley as he presides over an eight-course tasting menu at Brushstroke, his elegant Japanese restaurant in lower Manhattan. The chef who transformed French cuisine at his namesake Bouley restaurant has made an even greater leap by studying the culinary sensibilities of Japan.

“Hopefully we can indulge in the benefits and learn to share them,” he says. “And if we can find other cuisines that can help us without losing our own identity, then it’s all good stuff.”

Connecticut-born, French-trained chef and restaurateur Bouley opened Brushstroke in 2011 after years of study at Japan’s Tsuji Culinary Institute. Featuring seasonal tasting menus known as kaiseki, Bouley and his chefs (he oversees Brushstroke but doesn’t cook there) employ classical Japanese techniques to devise food that’s healthy, flavorful and aesthetically pleasing. The autumn menu included a kabocha and butternut squash soup, Alaskan rock fish, and smoked duck breast.

“I didn’t shift cuisines,” says Bouley. “I contribute what I think Americans are interested in, … so I’m sort of an editor. I work with them in terms of my indigenous ingredients and my techniques, and together we’ve been able to build almost a new cuisine.”

Bouley is just one of many restaurant owners and cooks inspired by the food of another culture. New York is a city of immigrants, so maybe it’s not surprising that the hands-on owners of the sturgeon shop on New York City’s Upper East Side are Chinese brothers from Hong Kong – and that the general manager of a century-old smoked fish emporium on the Lower East Side is from the Dominican Republic.

Or that the restaurateur behind one of the city’s most highly acclaimed sushi restaurants comes from an Italian-American background. Or that the brother and sister cooking Southeast Asian-influenced Cajun food in lower Manhattan are Jewish.

New York, after all, is a melting pot when it comes to dining. But what’s remarkable about so many of those bringing another culture’s food to the city’s tables is how open-heartedly and passionately they’re embracing their adopted cuisines, what they’re learning from them, and how they’re creating dishes that are refreshingly innovative.

At Tsuji, Bouley studied everything from the proper way to kill fish to the health benefits of using fermented foods. “I’ve always been a French-trained chef who works from raw ingredients,” Bouley says. “If I can enhance the raw ingredients, I can build a better experience for my customers.”

Which is exactly what Julie and Will Horowitz, the brother and sister from White Plains (30 miles north of Manhattan), are doing at Ducks Eatery [no apostrophe in Ducks], a homey, brick-walled restaurant in a single-story building in the East Village.

They come from a family tradition of cooking: their maternal grandfather was a fisherman on Long Island (“we source all our seafood from out there”), and their grandmother was a French-trained chef. Their paternal great-grandparents owned a delicatessen in Harlem.

“Just being here feels very powerful because we are reliving our family’s legacy,” says Julie, the GM and co-owner. The siblings still have their great-grandfather’s pastrami knife, “so every time we cook a brisket or pastrami, (for a special event) we slice it with his knife.”

What makes Ducks’ menu special is rooted in what Will calls “heritage techniques” – drying, curing, fermenting, pickling, smoking and aging – used at delis for generations. They merge these approaches with the flavors of the places they’ve traveled, especially New Orleans and Southeast Asia.

There’s spicy brisket jerky, Rocky Point oysters with jalapeno mignonette, and Yakamein soup (brisket and clams with sora noodles) [note: “sora” is correct – *not* soba] “which I believe is Creole for the ultimate hangover cure,” Julie says. Every week there’s a crawfish boil with Cajun spices. For dessert, how about a New Orleans favorite with an urban edge: beignets with dark chocolate espresso sauce.

“People who have eaten here are taken aback by how we look and what our background is,” says Julie, who’s 28 but doesn’t look old enough to drink. “Will (who’s 32) and I enjoy the shock element.”

Recently a customer from Memphis who said he smoked his own meat ordered the hickory-smoked St. Louis ribs. “There’s always the fear of ‘This isn’t authentic, what are you thinking, Yankee?’ ” Julie says. But the customer was happy, and “for the most part, we have really great feedback.”

Enthusiastic praise also greeted Alessandro Borgognone when he opened Sushi Nakazawa in the West Village in 2013. An Italian American, Borgognone had spent years working at Patricia’s, his family’s Italian restaurant in the Bronx. Then he saw the 2011 documentary, Jiro Dreams of Sushi, about Jiro Ono, an exacting Tokyo sushi chef in his eighties who earned three Michelin stars.

Borgognone emailed Ono’s deputy, Daisuke Nakazawa, and two weeks later got a call back. Nakazawa was interested in opening a restaurant in New York, “but first he had to get to know me as a person,” Borgognone says.

“My background is: If you have a great idea, I’d say, ‘come on, let’s do it.’ He wanted to know how many kids I have, the kids’ age, where they went to school, what they like to do for fun, and what I did for fun. He had to get to know me as a person before he would entertain the idea of going into business with me.”

By getting to know one another, as people and through food, the two men found that in cultural and culinary ways they weren’t far apart.

The main goal is very similar,” Borgognone says, “creating something that’s going to be perfect.” Sushi is “very different from a plate of spaghetti, garlic and oil, but again it’s very similar. Italian cuisine is very simple and minimalistic, and the simpler you are the better.”

Which echoes Borgognone’s and Nakazawa’s approach to sushi: “The fish is really the highlight, and the rice. It’s buying the best ingredients that we could find in order to make it perfect.”

While Nakazawa strives for perfection in his sushi creations, Borgognone has the same goal for the restaurant’s service and ambiance. “I paint every three months,” he says in his strong New York accent. “We keep it crisp; we keep it clean.”

Brash and confident, Borgognone, 34, says running a Japanese restaurant is shaping him not just as a businessman but as a person. “Instead of being a hotheaded Italian, I’ve learned you get more bees with honey,” he says.

Borgognone he feels a strong kinship with the Japanese way of relentlessly seeking to be the best. “They’re not content with just being good,” he says. “They are looking for perfection. And I think it’s rubbing off on me, not settling. Never settle.”

A similar attitude has made Sable’s the place to go for smoked salmon, sturgeon and pickled herring on the Upper East Side. Brothers Kenny and Danny Sze came from Hong Kong to New York City as teenagers and went right to work at the legendary Zabar’s on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where they learned how to select, trim and slice smoked fish.

“At Zabar’s, we started at the bottom,” Kenny says, but soon Kenny became manager of the appetizer department, a post he held for 12 years. “Zabar’s was like college for us. All the old-timers from Eastern Europe were there; now they’re all gone or retired. They taught us how to make pickled herring, whitefish salad, chopped liver, chicken soup with matzo balls.”

Danny felt the Upper East Side didn’t have a great place for the kind of smoked fish and caviar beloved by the city’s Jewish community. “I knew I was good, and that if I opened my own place it would be a success,” Kenny says. The Sze brothers have endeared themselves to their customers by giving out tastes and peppering conversation with the occasional Yiddish phrase, such as Chag Sameach (Happy Holiday).

Sable’s has now been open for a quarter century. “We’ve got to be good,” Danny says. “All our customers here are mavens; we have probably 80 to 90 percent Jewish customers. If we’re not good, forget it.”

He’s right. As the old joke goes: “What do waitresses ask their customers at delis on the Upper East Side? Is anything alright?”

Photos of celebrity customers paper the walls. “Rodney Dangerfield would come in here and say, ‘Hey, how come no taste for me? I don’t get no respect.’ He would stay and schmooze for a while,” Danny says. “Mayor (Ed) Koch was a regular customer too.”

On the Lower East Side, where so many Jewish immigrants landed a century or more ago, a similar story has unfolded at Russ & Daughters. Founded in 1914, the smoked fish counter on Houston Street has been owned by the same Jewish family for more than a century.

Yet the man whom Niki Russ Federman, the fourth-generation co-owner, calls “the soul of Russ & Daughters” is Herman Vargas, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic. In 1980, when he was 18, Vargas started there by washing dishes and peeling onions. He didn’t expect to stay too long – he’d come to the U.S. to get an engineering degree – but found the family atmosphere akin to the communal feeling he enjoyed in the Dominican Republic.

Soon Vargas moved up to work the counter selling everything from pickled herring to whitefish to rugelach. A regular customer came in, saw Vargas and asked to speak to the manager. “Now you have Puerto Ricans working here? What does a Puerto Rican know about schmaltz herring and smoked salmon?” the man said. In the ’80s, Vargas says, “anyone in New York who spoke Spanish was considered Puerto Rican.”

That customer “turned to me and says, ‘Wait on me? Not in a million years.’ I was like, wow, how will I break the barrier to let people know that I really want to serve them? … I made a conscious decision not to allow rejection be a hindrance.”

Vargas noticed that the manager greet customers by saying: “Vos makht ir, yid?” (“How are you doing?” literally: “How is a Jew doing?”). Vargas would take a little pad and phonetically write down, Vos makht ir, yid.

“So when a customer would come in, I’d say, ‘Vos makht ir, yid?’ And the guy just cracked up laughing. He says, what is this, a Puerto Rican speaking Yiddish? And he would say, ‘Can you cut lox?’ And I would say, ‘Well, if I can speak Yiddish, I can certainly cut lox.’ ”

Vargas practiced the art of cutting smoked salmon very thin because, “I knew it was important for people who wanted the maximum amount of slices out of every pound, and also some people believe that the thinner you cut it the better it tastes.”

Word on the street was Vargas was so skilled that you could read the New York Times through his smoked salmon slices. Calvin Trillin, who wrote about Russ & Daughters for The New Yorker, has a character in his novel, Tepper Isn’t Going Out, called Herman the Artistic Slicer.

And there are so many more stories: Italian-Brazilian restaurateur Marco Moreira became a celebrated sushi chef in the 1980s when just about every sushi chef was Japanese. He opened the sushi restaurant 15 East and also runs Tocqueville.

Moreira has just returned to his roots, having opened a sleek Brazilian eatery called Botequim at the Hyatt Union Square last September. [2014] “I am a Brazilian, non-Brazilian guy learning to make Brazilian cuisine,” Moreira says. “Now that I’m opening a Brazilian restaurant, I feel like a foreigner.”

Leonardo Vasquez left Guatemala twenty years ago and landed in Queens at a deli called Pastrami Queen that has since moved to Manhattan’s Upper East Side. A Puerto Rican manager taught Vasquez how to cook pastrami, corned beef and other Jewish delicacies, Vasquez says. “He could tell us in Spanish how to make matzo ball soup.”

Vasquez, 38, has spent more than half his life working at Pastrami Queen and makes some of the best pastrami and knishes in New York. “So famous the knishes … we sell them every day, so many,” he says. “The pastrami, same thing.” But don’t ask for the recipe. “We don’t give it away,” he says with a smile. “No way.”

And then there’s Marcus Samuelsson, the Ethiopian-born, Swedish-raised chef whose restaurant and bar, Red Rooster, serves African American comfort food and has helped reinvigorate Harlem. Like many great chefs and immigrants, Samuelsson’s ambitions seem boundless.

After tremendous success at New York’s Aquavit, Samuelsson moved to Harlem and spent three years learning about the neighborhood, its culture and culinary traditions. He won a Top Chef Masters competition, and in 2010 opened Red Rooster, which has brought countless people from other parts of the city and beyond to Harlem.

“You have to have a deeper interaction with the city,” Samuelsson said on NPR’s Fresh Air. “If you can connect the city, you can really change the footprint of dining.”

And maybe even the way people see the world.

— end —

Michael Shapiro is the author of A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives, and Inspiration. He writes about travel and food for magazines including National Geographic Traveler. Raised in New York, he discovered smoked salmon when he was three years old on the first day of a family vacation in Florida and ordered “pink fish” every morning for the rest of that trip.

Guess who’s slicing your sturgeon, NYC food story, Inspirato, Spring 2015

It’s no secret that the cooks making some of New York City’s best ethnic food didn’t grow up eating smoked salmon or pastrami sandwiches. On the upper east side I found two Chinese brothers selling fantastic sturgeon and the guys making the pastrami at Pastrami Queen on Lexington near 78th came from the Guatemalan pueblo of Solola. As an aside, it’s one of my favorite places there and when I told one of the chefs at Pastrami Queen that I’d been to his hometown he smiled as if to politely say “yeah, right.” Then I mentioned that Solola’s market days are Tuesday and Friday and that the village near Lake Atitlan is one of the few places in Guatemala where men still wear the traditional colorful clothing – his grin widened in recognition.

Immigrants Kenny and Danny Sze trained at Zabar’s and now run their own smoked-fish emporium on NYC’s upper east side.

—

Here’s the story in PDF form; from the Spring 2015 issue and in text below: Inspirato_Spring 2015_MS_NYC food

—

By Michael Shapiro

“There’s a lot to learn and the world is getting smaller,” says renowned chef David Bouley as he presides over an eight-course tasting menu at Brushstroke, his elegant Japanese restaurant in lower Manhattan. The chef who transformed French cuisine at his namesake Bouley restaurant has made an even greater leap by studying the culinary sensibilities of Japan.

“Hopefully we can indulge in the benefits and learn to share them,” he says. “And if we can find other cuisines that can help us without losing our own identity, then it’s all good stuff.”

Connecticut-born, French-trained chef and restaurateur Bouley opened Brushstroke in 2011 after years of study at Japan’s Tsuji Culinary Institute. Featuring seasonal tasting menus known as kaiseki, Bouley and his chefs (he oversees Brushstroke but doesn’t cook there) employ classical Japanese techniques to devise food that’s healthy, flavorful and aesthetically pleasing. The autumn menu included a kabocha and butternut squash soup, Alaskan rock fish, and smoked duck breast.

“I didn’t shift cuisines,” says Bouley. “I contribute what I think Americans are interested in, … so I’m sort of an editor. I work with them in terms of my indigenous ingredients and my techniques, and together we’ve been able to build almost a new cuisine.”

Bouley is just one of many restaurant owners and cooks inspired by the food of another culture. New York is a city of immigrants, so maybe it’s not surprising that the hands-on owners of the sturgeon shop on New York City’s Upper East Side are Chinese brothers from Hong Kong – and that the general manager of a century-old smoked fish emporium on the Lower East Side is from the Dominican Republic.

Or that the restaurateur behind one of the city’s most highly acclaimed sushi restaurants comes from an Italian-American background. Or that the brother and sister cooking Southeast Asian-influenced Cajun food in lower Manhattan are Jewish.

New York, after all, is a melting pot when it comes to dining. But what’s remarkable about so many of those bringing another culture’s food to the city’s tables is how open-heartedly and passionately they’re embracing their adopted cuisines, what they’re learning from them, and how they’re creating dishes that are refreshingly innovative.

At Tsuji, Bouley studied everything from the proper way to kill fish to the health benefits of using fermented foods. “I’ve always been a French-trained chef who works from raw ingredients,” Bouley says. “If I can enhance the raw ingredients, I can build a better experience for my customers.”

Which is exactly what Julie and Will Horowitz, the brother and sister from White Plains (30 miles north of Manhattan), are doing at Ducks Eatery [no apostrophe in Ducks], a homey, brick-walled restaurant in a single-story building in the East Village.

They come from a family tradition of cooking: their maternal grandfather was a fisherman on Long Island (“we source all our seafood from out there”), and their grandmother was a French-trained chef. Their paternal great-grandparents owned a delicatessen in Harlem.

“Just being here feels very powerful because we are reliving our family’s legacy,” says Julie, the GM and co-owner. The siblings still have their great-grandfather’s pastrami knife, “so every time we cook a brisket or pastrami, (for a special event) we slice it with his knife.”

What makes Ducks’ menu special is rooted in what Will calls “heritage techniques” – drying, curing, fermenting, pickling, smoking and aging – used at delis for generations. They merge these approaches with the flavors of the places they’ve traveled, especially New Orleans and Southeast Asia.

There’s spicy brisket jerky, Rocky Point oysters with jalapeno mignonette, and Yakamein soup (brisket and clams with sora noodles) [note: “sora” is correct – *not* soba] “which I believe is Creole for the ultimate hangover cure,” Julie says. Every week there’s a crawfish boil with Cajun spices. For dessert, how about a New Orleans favorite with an urban edge: beignets with dark chocolate espresso sauce.

“People who have eaten here are taken aback by how we look and what our background is,” says Julie, who’s 28 but doesn’t look old enough to drink. “Will (who’s 32) and I enjoy the shock element.”

Recently a customer from Memphis who said he smoked his own meat ordered the hickory-smoked St. Louis ribs. “There’s always the fear of ‘This isn’t authentic, what are you thinking, Yankee?’ ” Julie says. But the customer was happy, and “for the most part, we have really great feedback.”

Enthusiastic praise also greeted Alessandro Borgognone when he opened Sushi Nakazawa in the West Village in 2013. An Italian American, Borgognone had spent years working at Patricia’s, his family’s Italian restaurant in the Bronx. Then he saw the 2011 documentary, Jiro Dreams of Sushi, about Jiro Ono, an exacting Tokyo sushi chef in his eighties who earned three Michelin stars.

Borgognone emailed Ono’s deputy, Daisuke Nakazawa, and two weeks later got a call back. Nakazawa was interested in opening a restaurant in New York, “but first he had to get to know me as a person,” Borgognone says.

“My background is: If you have a great idea, I’d say, ‘come on, let’s do it.’ He wanted to know how many kids I have, the kids’ age, where they went to school, what they like to do for fun, and what I did for fun. He had to get to know me as a person before he would entertain the idea of going into business with me.”

By getting to know one another, as people and through food, the two men found that in cultural and culinary ways they weren’t far apart.

The main goal is very similar,” Borgognone says, “creating something that’s going to be perfect.” Sushi is “very different from a plate of spaghetti, garlic and oil, but again it’s very similar. Italian cuisine is very simple and minimalistic, and the simpler you are the better.”

Which echoes Borgognone’s and Nakazawa’s approach to sushi: “The fish is really the highlight, and the rice. It’s buying the best ingredients that we could find in order to make it perfect.”

While Nakazawa strives for perfection in his sushi creations, Borgognone has the same goal for the restaurant’s service and ambiance. “I paint every three months,” he says in his strong New York accent. “We keep it crisp; we keep it clean.”

Brash and confident, Borgognone, 34, says running a Japanese restaurant is shaping him not just as a businessman but as a person. “Instead of being a hotheaded Italian, I’ve learned you get more bees with honey,” he says.

Borgognone he feels a strong kinship with the Japanese way of relentlessly seeking to be the best. “They’re not content with just being good,” he says. “They are looking for perfection. And I think it’s rubbing off on me, not settling. Never settle.”

A similar attitude has made Sable’s the place to go for smoked salmon, sturgeon and pickled herring on the Upper East Side. Brothers Kenny and Danny Sze came from Hong Kong to New York City as teenagers and went right to work at the legendary Zabar’s on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where they learned how to select, trim and slice smoked fish.

“At Zabar’s, we started at the bottom,” Kenny says, but soon Kenny became manager of the appetizer department, a post he held for 12 years. “Zabar’s was like college for us. All the old-timers from Eastern Europe were there; now they’re all gone or retired. They taught us how to make pickled herring, whitefish salad, chopped liver, chicken soup with matzo balls.”

Danny felt the Upper East Side didn’t have a great place for the kind of smoked fish and caviar beloved by the city’s Jewish community. “I knew I was good, and that if I opened my own place it would be a success,” Kenny says. The Sze brothers have endeared themselves to their customers by giving out tastes and peppering conversation with the occasional Yiddish phrase, such as Chag Sameach (Happy Holiday).

Sable’s has now been open for a quarter century. “We’ve got to be good,” Danny says. “All our customers here are mavens; we have probably 80 to 90 percent Jewish customers. If we’re not good, forget it.”

He’s right. As the old joke goes: “What do waitresses ask their customers at delis on the Upper East Side? Is anything alright?”

Photos of celebrity customers paper the walls. “Rodney Dangerfield would come in here and say, ‘Hey, how come no taste for me? I don’t get no respect.’ He would stay and schmooze for a while,” Danny says. “Mayor (Ed) Koch was a regular customer too.”

On the Lower East Side, where so many Jewish immigrants landed a century or more ago, a similar story has unfolded at Russ & Daughters. Founded in 1914, the smoked fish counter on Houston Street has been owned by the same Jewish family for more than a century.

Yet the man whom Niki Russ Federman, the fourth-generation co-owner, calls “the soul of Russ & Daughters” is Herman Vargas, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic. In 1980, when he was 18, Vargas started there by washing dishes and peeling onions. He didn’t expect to stay too long – he’d come to the U.S. to get an engineering degree – but found the family atmosphere akin to the communal feeling he enjoyed in the Dominican Republic.

Soon Vargas moved up to work the counter selling everything from pickled herring to whitefish to rugelach. A regular customer came in, saw Vargas and asked to speak to the manager. “Now you have Puerto Ricans working here? What does a Puerto Rican know about schmaltz herring and smoked salmon?” the man said. In the ’80s, Vargas says, “anyone in New York who spoke Spanish was considered Puerto Rican.”

That customer “turned to me and says, ‘Wait on me? Not in a million years.’ I was like, wow, how will I break the barrier to let people know that I really want to serve them? … I made a conscious decision not to allow rejection be a hindrance.”

Vargas noticed that the manager greet customers by saying: “Vos makht ir, yid?” (“How are you doing?” literally: “How is a Jew doing?”). Vargas would take a little pad and phonetically write down, Vos makht ir, yid.

“So when a customer would come in, I’d say, ‘Vos makht ir, yid?’ And the guy just cracked up laughing. He says, what is this, a Puerto Rican speaking Yiddish? And he would say, ‘Can you cut lox?’ And I would say, ‘Well, if I can speak Yiddish, I can certainly cut lox.’ ”

Vargas practiced the art of cutting smoked salmon very thin because, “I knew it was important for people who wanted the maximum amount of slices out of every pound, and also some people believe that the thinner you cut it the better it tastes.”

Word on the street was Vargas was so skilled that you could read the New York Times through his smoked salmon slices. Calvin Trillin, who wrote about Russ & Daughters for The New Yorker, has a character in his novel, Tepper Isn’t Going Out, called Herman the Artistic Slicer.

And there are so many more stories: Italian-Brazilian restaurateur Marco Moreira became a celebrated sushi chef in the 1980s when just about every sushi chef was Japanese. He opened the sushi restaurant 15 East and also runs Tocqueville.

Moreira has just returned to his roots, having opened a sleek Brazilian eatery called Botequim at the Hyatt Union Square last September. [2014] “I am a Brazilian, non-Brazilian guy learning to make Brazilian cuisine,” Moreira says. “Now that I’m opening a Brazilian restaurant, I feel like a foreigner.”

Leonardo Vasquez left Guatemala twenty years ago and landed in Queens at a deli called Pastrami Queen that has since moved to Manhattan’s Upper East Side. A Puerto Rican manager taught Vasquez how to cook pastrami, corned beef and other Jewish delicacies, Vasquez says. “He could tell us in Spanish how to make matzo ball soup.”

Vasquez, 38, has spent more than half his life working at Pastrami Queen and makes some of the best pastrami and knishes in New York. “So famous the knishes … we sell them every day, so many,” he says. “The pastrami, same thing.” But don’t ask for the recipe. “We don’t give it away,” he says with a smile. “No way.”

And then there’s Marcus Samuelsson, the Ethiopian-born, Swedish-raised chef whose restaurant and bar, Red Rooster, serves African American comfort food and has helped reinvigorate Harlem. Like many great chefs and immigrants, Samuelsson’s ambitions seem boundless.

After tremendous success at New York’s Aquavit, Samuelsson moved to Harlem and spent three years learning about the neighborhood, its culture and culinary traditions. He won a Top Chef Masters competition, and in 2010 opened Red Rooster, which has brought countless people from other parts of the city and beyond to Harlem.

“You have to have a deeper interaction with the city,” Samuelsson said on NPR’s Fresh Air. “If you can connect the city, you can really change the footprint of dining.”

And maybe even the way people see the world.

— end —

Michael Shapiro is the author of A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives, and Inspiration. He writes about travel and food for magazines including National Geographic Traveler. Raised in New York, he discovered smoked salmon when he was three years old on the first day of a family vacation in Florida and ordered “pink fish” every morning for the rest of that trip.

May 1, 2016

Washington Post: Dylan Thomas’s Wales

I’ve long felt a kinship with Wales, perhaps because it’s where one of my favorite writers, Jan Morris, lives. Recently I had the chance to stay overnight and tour Dylan Thomas’s boyhood home in Swansea. Then I visited his other homes in Laugharne and New Quay. After the story ran in the Washington Post, I received a letter from a NY-based former embassy officer who helped Dylan clear customs on his last trip to America.

Below is the full uncut story, or click the link above for the slightly shorter version that ran in the Post — the letter is at bottom:

In Search of Dylan Thomas:

Seeking the elusive poet whose words brought Wales to the world

“This is not a museum,” says Annie Haden, the vivacious Dylan Thomas enthusiast who has restored the Welsh poet’s childhood home in Swansea, an industrial city on Wales’ south coast. “I’m the oldest thing in this house!”

About 60 years old, Annie, who tells me to call her by her first name, is displaying some Welsh hyperbole – she’s not the oldest thing in this loving memorial of Wales’ best-loved English-language poet. There’s a typewriter from the 1920s, colorful drawings based on phrases from Thomas’ poetry, antique copper kettles, even oblong filament lightbulbs that looked like something fashioned by Thomas Edison.

But she’s right – it’s not a museum. Annie, who has spent years refurbishing Thomas’s first home, is intent on making this a living breathing house, a place where the writer’s admirers can eat, drink, recite poetry, play music, and stay the night.

But she’s right – it’s not a museum. Annie, who has spent years refurbishing Thomas’s first home, is intent on making this a living breathing house, a place where the writer’s admirers can eat, drink, recite poetry, play music, and stay the night.

“Would you like a drink?” she asks me. “It is a Thomas house after all.”

The nation of Wales is gearing up to celebrate the centennial of Thomas’ 1914 birth so I thought I’d explore the coastal homes where he wrote and found solace, the beaches that made his spirit soar, and perhaps a favorite pub or bookstore. Like many of his countrymen, I appreciate Thomas’ work, though I can’t say I fully comprehend it all. I’m hoping that visiting places that shaped and inspired him will give me a deeper understanding of the artist and his words.

Thomas, who died before his 40th birthday, is often remembered as much for his excessive drinking and womanizing as for his art, but his poems, including “Do not go gentle into that good night” which he wrote for his dying father, have stood the test of time.

* * *

“And I fly over the trees and chimneys of my town, over the dockyards, skimming the masts and funnels … over the trees of the everlasting park … over the yellow seashore and the stone-chasing dogs and the old men and the singing sea. The memories of childhood have no order, and no end.” –Dylan Thomas, Reminiscences of Childhood

Located in the Uplands suburb of Swansea, Dylan Thomas’ birthplace is a handsome Edwardian two-story house on the steep part of Cwmdonkin Drive. Out front attached to the white stucco facade is a simple round plaque reading: “DYLAN THOMAS, A man of words, 1914-1953, was born in this house.”

I arrive on a rainy afternoon a few hours after touching down at London’s Heathrow; the brick-red tiles in the entryway are so worn they’re noticeably bowed. “We didn’t want to restore it because it’s part of the history of the house,” Annie says.

She puts a polished copper kettle on the stove. The time between the great wars, when young Dylan grew up, Annie says, was an “era when people never got rid of stuff like old copper kettles. People see relics and say, ‘My gran had one of those.’ That’s what brings ’em right in.” As we talk over tea about the home’s restoration, I can tell Annie loves words as much as Thomas did. “I’m a stripper,” she says, pausing for effect “and scrubber of wood.”

We climb a wide and time-smoothed wooden stairway to the upper floor and peer out the window of the back bedroom. Annie recalls Thomas’ poetic phrase about “ships sailing across rooftops.” In the bedroom once shared by Dylan’s parents, she points toward a row of houses, the Bay of Bristol in the distance. Because of the sloping hill down to the sea, it appears that boats bob atop Swansea’s roofs. “You get it,” Annie says, “when you see the view.”

In Dylan’s little room, illuminated by an antique gas lamp, a collectable copy of “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” sits on a small table. Lines from that book are painted on the walls. Annie asks if I notice anything. I read the lines and ask if one might have a mistake. She brightens and says there’s not just one mistake but several “because there’s nothing more empowering for a child than to say to an adult, ‘you’ve got it wrong.’ ”

In Dylan’s little room, illuminated by an antique gas lamp, a collectable copy of “A Child’s Christmas in Wales” sits on a small table. Lines from that book are painted on the walls. Annie asks if I notice anything. I read the lines and ask if one might have a mistake. She brightens and says there’s not just one mistake but several “because there’s nothing more empowering for a child than to say to an adult, ‘you’ve got it wrong.’ ”

She looks me up and down and asks, “How tall are you?” I tell her 5-5. “Well then, you’re a half inch taller than Dylan.” I concede I’m really 5-4-and-a-half. She seems pleased that I’m the same height as her beloved bard.

“I know Dylan,” she says. “I’m his mother now.” Then Dylan’s mother retreats to the kitchen to bring out lamb “that’s come nine miles to be with us tonight,” fresh pastry-crusted salmon from the nearby River Tawe, potatoes and a divine bottle of French Cotes du Rhone. Later she’ll top off the feast with a fresh-baked rhubarb-fruit tart.

I suggest the house is a labor of love, but Annie is quick to correct me. “It’s a labor born of frustration,” she says. “This boy of ours hasn’t been acknowledged and he should be.”

Annie says I can choose where I’ll sleep and invites me to stay in Dylan’s tiny boyhood room. But the room is barely bigger than the single bed so I opt for the guest room at the front of the house, which young Dylan called the “best room.”

Overlooking Cwmdonkin Park, where Dylan’s legs and imagination ran free, the spacious best room has a fireplace and brass candlesticks, a sink with a pitcher for wash water, a photo of Dylan and his wife, and a little crib. A book of Thomas’ poems waits on the nightstand.

* * *

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light. …

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

His parents’ first language was Welsh, but Dylan was raised speaking English so he would not sound working class, Annie says. Dylan took elocution lessons to get rid of his Welsh accent and read poems in the bathroom to train his voice because he realized it’s “not just what you say but how you say it.

Many of Wales’ early and modern poets write in a strict-meter form of Welsh, but Thomas became internationally known because he wrote so eloquently in English. Yet it was Thomas’ undeniable, intrinsic Welshness that gave his poetry so much strength, Annie says. “The meter and structure is old Welsh in form and the English loved it.”

Annie tells me that Thomas wrote hundreds of poems in this house, with his greatest output coming between the ages of 16 and 20. He worked in the morning and drank late, Annie says. Unfortunately Thomas couldn’t hold his alcohol, perhaps because he’s now believed to have been a diabetic, so he became a “performing monkey,” she says.

“Obnoxious behavior became his calling card. In London he was a performer. That’s not creative, and it’s tiring. He had to keep coming back and recharging here – not just this house, this town,” she says. “He’d say when he was on the train to London (that) he wasn’t going to England, he was leaving Wales. He was leaving his heart, he was leaving his safety.”

Like a protective mother, Annie denies that Thomas was an alcoholic. There’s “such a lot of work of such high quality that alcoholism is not considered.” I refrain from listing all the great writers who overindulged in alcohol. Annie refills my glass with Cotes du Rhone and I ask about Thomas’ most famous poem, “Do not go gentle into that good night” written as Dylan’s father, a frustrated poet, lay dying.

“Listen to it from a child’s point of view,” Annie says. “His father wouldn’t give Dylan the words he needed like ‘well done’ or ‘I’m proud of you.’ The work between father and son wasn’t finished.”

Keri Finlayson, a poet and frequent visitor to No. 5 Cwmdonkin Drive, tells me that young Dylan sat upstairs and listened to the sounds of voices floating up through the vents of his two-story home. “I like thought of words flowing around static objects,” she says. “I think of the boy in this tiny room, or in the bath learning to project” his voice.

Annie tidies up the kitchen, shows me how to turn up the heat, then bids me goodnight. I’m alone in the room where Dylan Thomas was born, his words on the nightstand for company.

The next morning I stroll along the lush byways of Cwmdonkin Park, where a dead tree standing more than 30 feet high has been carved into the shape of a pencil to honor the bard who grew up across the street.

The next morning I stroll along the lush byways of Cwmdonkin Park, where a dead tree standing more than 30 feet high has been carved into the shape of a pencil to honor the bard who grew up across the street.

At Swansea’s Dylan Thomas Centre, a stone’s throw from the Bristol Channel, are photos of long lists of words Thomas compiled as he wrote. He placed scrolls of rhyming words before himself like an artist’s palette, selecting just the right shade for the meaning he wished to convey.

Audio recordings play in corners of the center. As I listen I understand that, similar to James Joyce, the best way to comprehend Thomas is to hear his work read aloud, ideally in his own voice.

Thomas’ work has been called “thrillingly incomprehensible” but I can hear what the Welsh call hiraeth, an ineffable longing, and it all starts to make sense. Read aloud, Thomas’ poetry becomes music. Which makes me think that Bob Dylan, who took his name from the Welsh bard, is his natural heir: a musician who turns songs into poetry.

Now that most of Swansea’s industries have declined, the city no longer harbors the smokestack stench of Dylan’s time, but still I’m eager to explore the places to which he escaped as a teen. He called his bohemian group of friends the Kardomah Gang – they took their name from the café where they gathered.

In summer, the ruffians would camp out for a week or two by Rhossili Bay, drinking in the fresh air, clear night sky and copious amounts of ale and whiskey. Today the place attracts ice-cream-cone-toting families who hike among the bleating sheep on the lush green bluffs, gazing out at the broad crescent of sand and a pair of islands called Worm’s Head, accessible by a land bridge for less than an hour at low tide.

* * *

“When I think of that concentrated muttering and mumbling and intoning, the realms of discarded lists of rhyming words, the innumerable repetitions and revisions and how at the end of an intensive five hour stretch (from 2-7) prompt as clockwork, Dylan would come out very pleased with himself saying he had done a good days work, and present me proudly with one or two or three perhaps fiercely belaboured lines.” –Caitlin Thomas, Dylan’s wife

When Thomas was 23 he left the sanctuary of his family’s Swansea home and moved to another seaside abode, a place he called the Boathouse in Laugharne (pronounced Lahrn) overlooking Wales’ west coast. Walking up a stone path on a drizzly morning, I first arrive at his “word-splashed hut” perched like a bird’s nest on a cliff above the sea.

The converted shed where Thomas created some of his best work was exposed to Wales’ tempestuous storms and crashing ocean sounds. The room remains a churning sea of manuscripts, discarded drafts of verse, empty cigarette packs and literary journals.

Farther up the stone path is the house where Dylan, his wife Caitlin and their children lived. It feels like a small ship, with low doorways (five and half feet high, just enough for Thomas). The house been converted into a homey museum, called The Dylan Thomas Boathouse at Laugharne. In the parlor is a grand radio from the 1930s. While Thomas was traveling – to London, New York or Paris – his children would gather round the radio and listen to their father recite his poetry and stories on the BBC.

At the front desk I meet Maggie Richards, who grew up in Laugharne in the 1950s. She tells me Thomas’ play for voice, “Under Milk Wood,” which has been called “Ulysses in 24 hours,” was based mostly on Laugharne. Thomas changed the name to Llareggub, which spelled backwards is Buggerall. The first performance of the play in Laugharne was in 1958, she says.

“That’s how I got interested as a small child – I used to go and see these,” Richards says. After a time the community stopped performing the play, but the Laugharne Players re-grouped in 2006. “We’re doing it again this August,” says Richards, who directed the play in 2009, “but if half the players can’t be there, it might be a one-woman show.”

The scent of baking draws me to the basement kitchen where two young women are making bara brith, a lightly sweet Welsh bread. I ask about it and they cut me a slice to taste, on the house. Walking back down the rain-slickened path, I head to Brown’s Hotel which housed one of Thomas’ favorite pubs. He spent so much time there he gave the pub’s phone as his contact number, but the hotel was closed for renovations.

Nearby is Corran’s Books in a weathered stone building with a bright blue door. Owner George Tremlett, author of a biography of Caitlin Thomas, says Laugharne is where Dylan Thomas matured as a writer.

“His early work wasn’t very good” Tremlett says. “It was here that he found whatever it was he needed to make the mix.” What made this town so right for Thomas? It’s an egalitarian town, Tremlett says. “The rich man counts for very little here. And it’s very easy going – I think that fitted him like a glove.”

“His early work wasn’t very good” Tremlett says. “It was here that he found whatever it was he needed to make the mix.” What made this town so right for Thomas? It’s an egalitarian town, Tremlett says. “The rich man counts for very little here. And it’s very easy going – I think that fitted him like a glove.”

In his last years Thomas and his family moved to New Quay, a seaside resort that has created the Dylan Thomas Trail, a set of sights related to the poet. Number 8 is May’s Designs where the owner, a young ebullient woman named May Hopkins, has painted Thomas quotations on the walls. “When one burns one’s bridges,” reads a Thomas line, “what a nice fire it makes.” Another says: “He who seeks rest finds boredom, he who seeks work finds rest.” Says Hopkins: “That’s up for the girls who work here so they can take the hint.”

The shop sells driftwood, paintings, and photos of Dylan and Caitlin. Hopkins is proud that Thomas lived in her town. “I do like his work,” she says, “but I don’t understand a lot of it.”

I walk along a concrete pier and look out to the “fishing-boat-bobbing sea” that inspired Thomas in his last years. A lone bottlenose dolphin gracefully arcs above the water, a seal clasps a silver fish that flaps in vain.

* * *

“It is the measure of my individual struggle from darkness toward some measure of light.” –Dylan Thomas’ “Poetic Manifesto”

Before leaving Wales I attend a lunch with Thomas’ granddaughter, Hannah Ellis, who says that Dylan “clearly had a very happy childhood.” However his world was shattered in February 1941 after the German blitz leveled much of Swansea, leaving 230 dead and 7,000 people homeless in mid-winter. “Our Swansea is dead,” he writes in “Return Journey,” a BBC radio play. The play isn’t simply an elegy for his hometown, Ellis said, it’s his attempt to rebuild Swansea with his words.

Like Annie Haden, Ellis believes her grandfather hasn’t received the recognition he deserves. She hopes the upcoming centennial celebrations will change that and introduce a new generation to his work. “When I tell someone I’m Dylan Thomas’ granddaughter,” Ellis says, “I don’t want them to say ‘Who?’ ”

After almost a week in Dylan Thomas’ Wales, I have a much better sense of the poet, but there’s one last place I feel compelled to visit: the stately National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth, where some of Thomas’ possessions remain. I sit with a curator, with the delightfully Welsh name of Ifor Apdafydd, in a high-ceilinged room. Apdafydd shows me a map of downtown Swansea that Thomas drew, a betting slip with odds on horses, a Pan American airline ticket, and a letter to his uncle thanking him for a gift and praising the Disney movie Dumbo.

The curator then unwraps a leather wallet containing Thomas’ passport. “Can I hold it?” I ask. Apdafydd hesitates, then consents. I slowly turn the yellowed pages and see stamps for France, Italy, and Iran, where Thomas traveled in 1951 to write a script for the Anglo Iranian Oil Company.

Then there’s the final stamp: a New York entry into the U.S. in 1953, where, five days after allegedly boasting he’d knocked back “eighteen whiskeys, a record,” Thomas died at St. Vincent’s Hospital.

Then there’s the final stamp: a New York entry into the U.S. in 1953, where, five days after allegedly boasting he’d knocked back “eighteen whiskeys, a record,” Thomas died at St. Vincent’s Hospital.

After that last stamp, the better part of the passport is blank, no mark of a return to Britain. I survey the grand room in this house of words that Thomas helped build. “So many empty pages,” I say in a low voice as a wave of sadness washes over me. “So many pages left unfilled.”

——————————–

Shortly after this story appeared in the Washington Post in August, 2013, I received this letter:

Dear Mr. Shapiro,

I enjoyed reading your article in today’s Washington Post and I have a bit of relevant information to add to it. If you still have access to his passport I’m pretty sure you’ll find my signature at the bottom of his U.S visa and there is a little story connected with it.

At the time I was a new vice consul at the American Embassy in London. I happened to be passing through the reception area of the visa section when I encountered a noisy confrontation between one of the reception clerks and a man who looked like an impoversihed hobo. The clerk was demanding that the visitor go away and I overheard their conversation. When I understood that the shabby visitor was actually Dylan Thomas, I immediately invited him to my office and issued him an American visitor’s visa. Unfortunately, his visit to America ended in tragedy but I retained an abiding interest in his poetry.

Edward

April 12, 2016

Vancouver leads Canada’s sustainable seafood movement, Spring 2016

Chef Ned Bell of the Four Seasons’ YEW restaurant, buys sustainable fish at Vancouver’s wharf. Photo by Michael Shapiro

Though most of humanity doesn’t realize it, our survival depends on our oceans. During the past couple of centuries we overfished and polluted oceans to the point where many species are on the verge of collapse. But most of us love wild seafood and have no intention of curtailing our appetite. That’s why the sustainable seafood movement is essential. In the U.S. it’s been led by the Monterey Bay Aquarium; the Canadian counterpart is the Vancouver-based Seafood Watch but the true stars of the movement there are the top chefs who insist on serving fish whose stocks are not depleted. Last fall I spent a few days in Vancouver tracing sustainable seafood from fishing boats to markets to the city’s finest restaurants.

Here’s the PDF of my story for Inspirato, which appeared in Inspirato magazine. Click:

April 2, 2016

Seeing Yosemite through a blind man’s vision, Alaska Beyond, April 2016

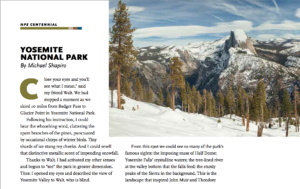

Screen shot of first page of essay in Alaska Beyond. Click on PDF below to read the full story.

“Close your eyes and you’ll see what I mean,” says my skiing companion Walt as we traverse the 10-mile trail to Yosemite’s Glacier Point. My friend Walt is legally blind, unable to see the grandeur of Half Dome and the park’s other landmarks. But on that day in February 2009, he showed me that there are many ways of seeing, feeling and sensing the park’s majesty. When my editor at Alaska Beyond (Alaska Airlines’ inflight magazine) asked me to write an essay for a special feature last April to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the National Park Service, skiing with Walt was the first thing that came to mind.

Here’s the PDF of this short essay: Yosemite essay

April 1, 2016

CritBit wins top prize on ‘Top Inventor’ reality show

CritBit wins top prize on Top Inventor reality show

BY FRANK FARKAKTE

DISASSOCIATED PRESS

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) — A wearable device called the CritBit has earned Petaluma inventor Michael Shapiro $1 million on the Turner reality show “America’s Greatest Makers.”

The device, about the size of watch, can be worn on one’s wrist or belt. It contains language software programmed to recognize criticisms and emits a small beep when a critical comment is uttered. It has a vibration setting for the hearing impaired.

A prototype of the new CritBit. The device recognizes and tallies criticism uttered by its wearer.

The CritBit tallies the number of criticisms uttered in a day, week, month or year.

“So many of us are critical to our friends, co-workers and especially our spouses, but we don’t always realize it,” said Shapiro, a resident of Petaluma, Calif. “The goal of the CritBit is simply to make us aware of when we’re being critical.”

“America’s Greatest Makers” was sponsored by Intel, and is being televised on Turner Broadcasting channels nationwide.

Intel CEO Brian Krzanich will present the prize to Shapiro on the air in May. The show promoted Intel’s “Make it Wearable” challenge to showcase makers inventing wearables and smart connected consumer devices powered by Intel Curie technology.

Shapiro said he doesn’t have a technology background but worked with Dragon Speech Recognition engineers after coming up with his idea.

FitBit, which makes wearable devices that track the number of steps taken in a day, initially threated to sue Shapiro for copyright infringement but now is in talks to acquire the CritBit.

“I’m thrilled,” Shapiro said, “not just to win the $1 million prize but to get this idea out there so we can live in a less critical world. When I tried the prototype the first day I tallied 69 criticisms – I couldn’t believe it.”

Added his wife, who declined to give her name: “I could.”

Asked what he plans to do with the $1 million prize, Shapiro said, “I’m finally going to be able to buy that big house in Sonoma County. Or small house. Or make a down payment. I don’t know, maybe after taxes I’ll just pay off some debts and get one of those new $35,000 Teslas.”

Then he added: “Housing in this county is so damn expensive.”

His CritBit emitted a small beep.

March 11, 2016

Global Soul: Chilean author Isabel Allende at home in SF Bay Area, 2016

Ever since I read The House of the Spirits in the 1980s I’ve adored Isabel Allende. She’s a natural-born storyteller, warm-hearted and insightful with a wicked sense of fun. I had the opportunity to interview her for my 2004 book of interviews with writers, A Sense of Place. I was elated last year when a magazine asked me to write about her adopted home, the San Francisco Bay Area, and how Allende has found her place so many mile from home. Ultimately this story is about Allende and her remarkable ability to transcend tragedy.

The PDF of the story from Inspirato magazine is just below, the text follows beneath the PDF:

Inspirato Magazine_Spring 2016_Isabel Allende

GLOBAL SOUL

Best-selling Chilean author Isabel Allende, now at home in the San Francisco Bay Area, transcended tragedy to touch the hearts of millions of readers worldwide

By Michael Shapiro

Halfway through an hourlong talk to a group of aspiring writers last August, Chilean author Isabel Allende was asked: “If you were a character in an Isabel Allende novel, where would you put yourself?”

Without missing a beat the petite writer said: “First of all, I would have long legs, I would be beautiful, I would be stunning, and smart, very strong and independent. What was the question?”

“Location: where would you be?”

“In bed with someone,” she shot back. “It doesn’t matter the town.”

Isabel Allende, photo by Mary Ellen Mark, 2015

Hanging on the beloved author’s every word, the audience in Marin County (just north of San Francisco) erupted in laughter. And just about everyone who asked her a question that day at Book Passage, a bookstore in Corte Madera, addressed her simply as “Isabel” as if they were talking to an old friend.

The arc of Allende’s life could be the story of one of her novels. Born into a family of Chilean diplomats, she spent her first years in Peru. As a young child she returned to Chile, grew up in her grandfather’s spectral home, became a journalist, married young and had two kids. Then her world fell apart.

Her father’s cousin, Salvador Allende, had been elected president of Chile in 1970, but on Sept. 11, 1973, during a brutal right-wing coup, he shot himself, choosing to die rather than be captured. The dictator Augusto Pinochet seized power and, after several people she knew disappeared, Isabel fled Chile with her husband and two young children in 1975 and settled in Venezuela.

Yet Allende’s most difficult days were years ahead. In her immediate future was fantastic success. As her grandfather neared death, she began writing a long letter to him, and kept writing after he died. Allende showed the letter to her mother, and though the matriarch was appalled that her daughter would reveal the family’s secrets, even as fiction, she encouraged her to publish a book.

That letter was the basis for Allende’s first novel, The House of the Spirits, published in 1982. Initially rejected by several Spanish-language publishers, the magically realistic book first came out in Argentina and fast became an international bestseller. In 1993, it was made into a film starring Meryl Streep and Antonio Banderas.

“I started a letter for my grandfather almost knowing that he would never be able to read it, a spiritual letter – it was a letter to myself really,” Allende told David Frost in a televised interview. “I wanted to tell him that I remembered everything he ever told me, and he could go in peace because it would not be lost. I think The House of the Spirits was like a crazy attempt to recover everything I had lost — my country, my family, my past, my friends — and put everything together in these pages. It was something I could carry with me and show to the world and say, ‘This is what was; this is my world.’ It gave me a voice. Incredibly it was a success from the beginning and allowed me to continue as a writer.”

In 1987, Allende came to the San Francisco Bay Area on a book tour and fell in love at first sight, with the place and with an attorney, William Gordon, who’d attended one of her readings. He lived in San Rafael, in the heart of Marin County. Allende married Gordon the following year and made a home in the Bay Area.

“I have been living in Marin County for 27 years, and I love it,” she told me last fall. “Who wouldn’t? There is water, hills, trees and trails everywhere and good weather. This a place of innovation, diversity, young energy and visionary creativity.”

There was a time when Allende, 73, never thought she’d find a place that felt like home. “I have always been a foreigner,” she said, “first as daughter of diplomats living briefly in different countries, then as a political refugee and now as an immigrant.” In her 2003 memoir, My Invented Country, she writes: “Until only a short time ago, if someone had asked me where I’m from, I would have answered, without much thought, Nowhere.”

There was a time when Allende, 73, never thought she’d find a place that felt like home. “I have always been a foreigner,” she said, “first as daughter of diplomats living briefly in different countries, then as a political refugee and now as an immigrant.” In her 2003 memoir, My Invented Country, she writes: “Until only a short time ago, if someone had asked me where I’m from, I would have answered, without much thought, Nowhere.”

But that’s changed. In our recent interview, she said: “I came here as an immigrant with a sense that I didn’t belong anywhere and somehow here I found space, privacy; I feel very safe. There is nothing extraordinary about being an immigrant here.”

Allende is now an American citizen. “My roots are in Chile, but I have found my home in the Bay Area, where my son, my daughter-in-law, my grandchildren and most of my friends live, and where I have written 18 books. I hope to spend the rest of my life in this wonderful place.”

Her time in Marin, however, hasn’t been all sunsets and Chardonnay. In the early 1990s, her daughter, Paula, was stricken by a rare disease and spent a year in a coma before dying in her mother’s arms at age 29. Allende says her memoir about that year, titled Paula, is her most deeply felt book and has had the greatest resonance with readers.

“It forced me to go inside,” Allende told me years ago when I interviewed her for my book, A Sense of Place, a collection of interviews with writers. “I’m a very out-there person; I’m into the story,” she said. “The whole experience of the death of my daughter and writing a book forced me to go on a journey into myself, which in a way was a threshold for me. I left behind my youth with that experience. That was the year that I turned 50. It was like throwing everything overboard in very deep ways.”

Paula was “an exercise in memory and love” and cathartic to write, Allende said. “That’s the book that was written with tears. It was so raw that people connect to it as a form of honesty.” Though she cried while writing every page, Paula wasn’t painful to write, she said. “It was so healing; it was wonderful.”

In an on-stage conversation last November in San Rafael, Allende said, “It seems as though Paula is still touching people throughout the world. She is still present and will always be present, which adds beauty and richness to my life.”

Elaine Petrocelli, owner of Book Passage, said Allende’s presence, in the store and throughout Marin, has been transformational. “Isabel first came to speak at Book Passage almost 25 years ago. That night, something profound changed in my life and in the life of our store,” Petrocelli said. “By example she teaches kindness, forthrightness, commitment, giving and laughter. Each book she writes is so elegantly crafted that the reader is unaware of the work that brought the story to life. Her characters are so real that they remain with us long after we close the book.”