Michael Shapiro's Blog, page 12

August 10, 2012

Self-publishing tips

I’m on a panel at Book Passage today on self-publishing. The two main ways to go about this are: produce a print book or publishing an e-book. Both have their advantages. For an art or photography book, there’s no substitute for print. But e-books have the potential to reach all corners of the globe without a physical distribution network. You don’t have to chop down trees, secure warehouse space, or take returns. But here’s the thing: whenever I write a book I want to support the bookstores that have nurtured my career, most of all Book Passage – so my goal is to find a way to do e-books that include independent stores.

I’m on a panel at Book Passage today on self-publishing. The two main ways to go about this are: produce a print book or publishing an e-book. Both have their advantages. For an art or photography book, there’s no substitute for print. But e-books have the potential to reach all corners of the globe without a physical distribution network. You don’t have to chop down trees, secure warehouse space, or take returns. But here’s the thing: whenever I write a book I want to support the bookstores that have nurtured my career, most of all Book Passage – so my goal is to find a way to do e-books that include independent stores.

Following are some links that could be useful for those interested in self-publishing.

1. For inspiration, read this account in WaPo about Nyree Bellville. She’s a close friend of my wife and hit bottom professionally a couple of years ago when her publisher cut her loose. So she self-published and hasn’t looked back.

2. For nuts and bolts, this guide from CNET has 25 tips on self-publishing both bound and e-books. Among the overarching suggestions: have a clear goal for your book. Niche books “with a well-defined topic and a nice hook” do best. There’s practical advice here too, such as create your own ISBNs and become your own publishing house. You can buy sets of 10 ISBNs at a discount; buying in bulk saves money. And hire a copy editor and possibly a book doctor, nothing turns away readers like a poorly edited book. Finally design a cover with a central graphic element so it looks good small.

3. CNET’s guide to the leading publishing platforms, including Smashwords, Bookbaby and Scribd, can help you decide which platform is best for your book. Naturally you can place the book on several platforms.

And here are some general tips about e-publishing:

Study the market: Know who your competitors are. See who’s at the top of your niche and figure out how they got there. Did they do promos?

Know your strengths: Are you good at social media, graphics, uploading? Figure out what you can do and where you need to hire help.

Series work: Self-publishing builds on itself. One book may or may not do well, but you can build momentum with a series.

Distinguish yourself: It’s a crowded field – your book needs to stand out, either for it originality, writing quality, or approach.

Covers are key: E-books are judged by their covers – you want to stand out and make it look good when it’s the size of a postage stamp.

Keep evolving: Unlike in print, e-books can be updated. If a book isn’t selling well, try a new cover or add updated text.

Have fun with it: This is a brave new world and offers unprecendented opportunities to share your work. So produce the best work you can and keep promoting it so others can enjoy it.

June 6, 2012

Wild About Kenya: Safari story for Private Clubs magazine

When an editor asks if you’d be “willing” to go to Kenya on a safari led by an outfitter known as among the best — if not the best — in Africa, it doesn’t take long to blurt out yes. And that’s how I ended up celebrating my birthday with a group of new friends with an outdoor champagne breakfast in a meadow with a view of Mt. Kenya. And that was just how it started. After a visit to a chimpanzee reserve and seeing wild rhinos, that birthday ended with a party in William Holden’s suite at the Mt. Kenya Safari Lodge.

For the rest of the story, at least the part that could be published, or read text below. Note: my story appeared in the March-April 2012 issue of Private Clubs magazine, which goes to members of a country club association. In the magazine the photos were by friend and colleague Kevin Garrent, but I took the photos in the text below.

Wild About Kenya, Again

Here’s why safari fans are migrating back to this eye-popping East Africa animal kingdom.

BY MICHAEL SHAPIRO

It’s afternoon and we’re now in the heart of Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve, in the northern Serengeti. I’m astounded by all I’m seeing as our Micato tour group explores this East African terrain in an open-air Land Rover. A parade of elephants stomps across the dun-colored plain, giraffes nibble the tops of 20-foot acacia trees, and hundreds of zebras trot across the landscape. As we drive deeper into the Mara, it gets even better: Wildebeests congregate by the thousands. They’re preparing for the world’s largest land migration, when 1.5 million of them thunder south across the Serengeti into Tanzania annually, a jaw-dropping phenomenon unique to East Africa each fall.

It’s a spectacle once again piquing the curiosity of adventure-minded sightseers. Beginning in the 1990s, when southern Africa’s popularity soared as new luxury resorts like Singita grabbed an ever-larger share of the safari market, East Africa became an afterthought for some travelers. Violence that followed Kenya’s disputed 2007 election led to a further dip in tourism, but those numbers have rebounded as the country has stabilized, with more than 1 million visitors and better than 10 percent growth in recent years. With this steady increase has come the high-dollar renovations of remote safari clubs and historic hotels, making those properties more luxurious and Kenya more appealing and poised for a comeback.

But the country’s big draw remains this animal-rich national reserve, situated in southwest Kenya on the Mara River. Unlike the smaller reserves in southern Africa, this park seems endless; at about 600 square miles, there’s no way we can see all of it in the three days we’ll spend here.

Back at our base, the riverside Fairmont Mara Safari Club, our wildlife viewing continues: Submerged hippos groan and crocodiles slosh through the water, in an uneasy detente. A bee-eater, an iridescent green and scarlet bird about the size of a robin, snatches an inch-long yellow bee out of the air and lands on a branch, expertly yanking out its stinger before consuming it.

The river surrounds the hotel’s 51 canvas-walled rooms on three sides. These “tents” don’t match Singita for spaciousness and opulence, but they’re well-appointed with their four-poster pillow-top beds and verandas overlooking the river. As inviting as the rooms are, nothing can top the nonstop show of cavorting hippos and the round-the-clock intimate connection with nature one feels on the banks of the Mara.

At dusk, we head out in Land Rovers to the hotel’s boma, a communal circle deep in the forest, where locals in indigenous dress entertain us with tribal Kenyan music around a blazing campfire. A sumptuous buffet and well-stocked bar have been set up in the bush – the feeling is heady and transcendent. I’d had high hopes for this trip to the Mara, and already these almost unrealistic expectations have been exceeded.

On a hot-air balloon ride the next morning, we can see for miles. Elephants and zebras cast long shadows, creating Escherlike patterns on the land. At a reserve for white rhinos, we watch young bulls spar, horn against upturned horn, from just 15 yards away. There’s no fence, so when these three-ton animals start rumbling toward us, we scamper down the hill as wardens place their bodies between the rhinos and us.

Back in our Land Rover, we traverse the savannah and hear a report crackling over the radio: A leopard is feeding in a tree a few miles away. From a distance, we see a herd of Jeeps circling a tree – the leopard is up in the branches with an eviscerated white goat poached from a nearby Maasai village. The leopard feeds on the carcass, then hops down, its stomach distended, to rest on the ground.

Years ago, this leopard would probably have fallen prey to vengeful Maasai hunters; today the Maasai understand that big cats keep the tourists coming, our guide tells us. Now that the Maasai are compensated for lost livestock and share in tourism revenue, our guide says there’s a good chance hunters won’t kill that leopard – one more sign of change in ever-evolving East Africa.

NAIROBI – GATEWAY TO KENYA AND THE MARA

Some safari tours quickly leave Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, for the remote regions, but our Micato group spends a full day exploring the city and environs with our guide George Omuya. “South Africa is like a European country,” Omuya says as we drive through Nairobi. “To see the real Africa, you have to come to East Africa.” He’s speaking not just of the city but of the seemingly boundless Maasai Mara.

Four urban attractions you’ll want to see:

1. David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, an orphanage for baby elephants and rhinos in Nairobi National Park where dozens of the animals slurp milk from big upturned bottles and cavort through an enclosed mud pit. More than 120 have been reared here; more than half have successfully returned to the wild. On our visit, a toddler elephant with reddish mud caked on her back approaches me and lets me place my hand on her head. Her skin feels rough and bristly. “She don’t do that much,” says a handler. “She’s just starting to trust people again.” I ask the handler the elephant’s name. “Murka” he says. “They killed her mama. We found Murka with a spear 10 inches deep in her head.”

2. Giraffe Manor, a majestic 10-room lodge inside a private animal sanctuary. Wild Rothschild giraffes come around when hungry, which is most of the time since they eat about 140 pounds of food daily. Some members of our group place marble-size food pellets between their lips and get a soft kiss as a giraffe claims its treat. Not me; I put some pellets in my palm and feel the velvet nuzzle of the giraffe’s muzzle as she delicately takes the food.

3. Karen Blixen’s modest stone farmhouse, where the Out of Africa author lived from 1914 to 1931. In the writer’s study, I saw her antique Corona typewriter and imagined her gazing out at the rolling Ngong Hills and conjuring tales of romance inspired by the landscape. That’s when it hit me: It’s the hills and the visions of what’s beyond them that made Out of Africa so rich. Stepping on this hallowed soil made me feel I’d landed in this evocative place.

4. The Mukuru slum, a densely packed city within a city of mud streets, storefront vendors, rundown churches, smoky fires, stray cats, junkyard dogs – and hundreds of thousands of people. At a complex operated by AmericaShare (a nonprofit founded by Micato Safaris), an oasis in this sodden slum, you’ll find a basketball court funded by a young safari-goer’s bar mitzvah money, a computer center where kids learn tech skills, and a library full of books.

NANYUKI – A SPELLBINDING SAFE HAVEN FOR RHINOS AND CHIMPS

At a Nairobi airstrip, the loud chop of the propeller signals it’s time for our tour group’s departure. We board the 12-seater and fly about a half-hour north to Nanyuki, near the equator. Home to reserves that work to preserve threatened species, the Nanyuki region is an ideal place to witness Kenya’s efforts to preserve endangered wildlife.

We settle into the storied Fairmont Mount Kenya Safari Club, a sprawling French colonial hotel and cottage complex that straddles the equator. In the hotel’s courtyard, where proud peacocks strut, we stand with one foot in the northern hemisphere, the other in the southern.

Sunrise brings a crystal-clear view of towering Mount Kenya, Africa’s second-highest peak (after Kilimanjaro). We ride horses for an hour through lush meadows to a champagne breakfast in a clearing.

Later, driving through the protected Ol Pejeta Conservancy, we see black rhinos lumber across green fields. The rhino population had been decimated due to hunting for their horns, used for sword handles in Yemen, but slowly they’re making a comeback.

Opened in agreement with the Jane Goodall Institute, among others, the Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Ol Pejeta is home to dozens of chimps that suffered unspeakable cruelty before being rescued. We watch them swing through the trees; some come to the fence seeming to greet us. I’ll long remember the intelligence and apparent resignation I saw in those chimps’ eyes.

ESSENTIALS

Best time to go: July to October is best for game viewing. About 1.5 million wildebeests arrive in the Maasai Mara National Reserve in late spring and early summer of each year; they stay until fall, when they migrate south again.

Tour outfitter: Micato Safaris outfits bespoke trips to Kenya and Tanzania. The company is known for its personal touch; co-founder Jane Pinto greets arriving clients at their hotel, and she and her husband Felix invite all their tour groups to their home for lunch or dinner. 800-642-2861; micato.com

Lodging: In the last few years, $35 million in renovations have helped add to the luxury level of these Fairmont hotels.

• In Nairobi, the historic Fairmont Norfolk dates back to 1904 and has counted President Theodore Roosevelt among its many guests. Besides 165 rooms, the hotel now sports achic new wine bar; a sleek steakhouse; an opulent tea room that conjures visions of early 20th-century Africa; and an open-air restaurant under a conservatory-style roof. Head to its spa for a full range of refreshing services. Rates from $329. 800-441-1414; fairmont.com/norfolkhotel

• The Fairmont Mount Kenya Safari Club, a French colonial hotel on the equator at the base of Mount Kenya, has 120 rooms in cottages, villas, and suites. Its amenities include a nine-hole golf course. Actor William Holden founded the club in the 1950s and would retreat there to get away from the Hollywood scene. Club members once included luminaries such as Winston Churchill, Bing Crosby, Lord Mountbatten, and John Wayne. Rates from $535, including two game drives per day. 800-441-1414; fairmont.com/kenyasafariclub

• Get cozy and comfortable in luxurious tent cabins at the Fairmont Mara Safari Club in the Maasai Mara National Reserve. Its 51 tent cabins overlook the Mara River, with its hippos and crocs. All units come with private bathrooms and some have outdoor showers. Rates from $499. 800-441-1414; fairmont.com/marasafariclub

June 1, 2012

Hugh Laurie’s in the house

Usually when an actor takes the stage to play music it’s mediocre at best. But Hugh Laurie can really play piano and has assembled a top-shelf band from New Orleans. I profiled Laurie in advance of last Tuesday’s show in Napa, which was superb. Here’s my story from The Press Democrat, below:

Hugh Laurie plays guitar and piano, and sings standards with his New Orleans blues band.

Hugh Laurie is in the house

By Michael Shapiro

The Press Democrat

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

After listening to British actor Hugh Laurie’s rollicking album “Let Them Talk,” a gumbo of New Orleans blues styles, one has to ask: What can’t Laurie do?

You know him as the acerbic diagnostician, Dr. House, on the TV show “House.” And you may have sensed he could play piano during those snippets of the show when Laurie taps the keys.

But did you know Laurie was a champion rower in his youth? His father was an Olympic gold-medal-winning oarsman, and Laurie was on track for the Games before mononucleosis laid him low.

While a member of the Cambridge Footlights, an amateur acting troupe that has launched many careers, Laurie met and dated actress Emma Thompson. They remain good friends.

He then turned his talents to sketch comedy, gaining fame as half of the Fry and Laurie team with his close friend Stephen Fry.

The release of “Let Them Talk,” with guest musicians including soul singer Irma Thomas, keyboardist Dr. John and Welsh vocalist Tom Jones, puts Laurie on the musical map. Listening to the album is like a steamy stroll through the French Quarter on a sweltering summer night.

“Let Them Talk,” released last year, has reached the top of the Billboard blues chart and is a Gold record in the U.K. Laurie’s piano-playing has garnered favorable reviews, though there are moments when his voice sounds thin and reedy.

On the PBS show “Great Performances” Laurie, who has battled depression, said he’s drawn to the blues because the music evokes feeling.

“Blues can bring out in me every single human emotion,” Laurie said, “or at least every emotion that I know of. ‘Let Them Talk’ is an odyssey — my destination is the holy city of New Orleans.”

Laurie plays piano on “After You’ve Gone,” sung by his longtime hero, Dr. John, a highlight of the album.

“I played the piano for Dr. John — I can’t believe I’m saying that sentence,” Laurie said on the PBS show. “I’ve worshiped Dr. John, I mean really worshiped Dr. John, for as long as I can remember, and for me to be actually playing while he sings … I left the studio that day and I got into my car and actually wept.”

It wasn’t just Laurie’s appreciation of Dr. John, however, that led him to play piano.

“I tended to favor the piano over the guitar because it stays in one place, which is what I like to do,” he says on his website. “Guitars appeal to the footloose, the restless. I like sitting a lot.”

So what’s a British actor — don’t be fooled by the American accent he uses on “House” — doing headlining an album of New Orleans blues classics?

“I was not born in Alabama in the 1890s. You may as well know this now,” writes Laurie, 52, on the album’s website. “I’ve never eaten grits, cropped a share, or ridden a boxcar. … Let this record show that I am a white, middle-class Englishman, openly trespassing on the music and myth of the American south.”

He goes on: “If that weren’t bad enough, I’m also an actor: one of those pampered ninnies who hasn’t bought a loaf of bread in a decade and can’t find his way through an airport without a babysitter.

“Worst of all, I’ve broken a cardinal rule of art, music, and career paths,” he says. “Actors are supposed to act, and musicians are supposed to music. That’s how it works. You don’t buy fish from a dentist, or ask a plumber for financial advice.

So why listen to an actor’s music?

His simple answer: he loves the blues with all his heart, provenance be damned.

“The blues have made me laugh, weep, dance. New Orleans was my Jerusalem,” he says, noting that the music fills him up.

“I could never bear to see this music confined to a glass cabinet, under the heading Culture: Only To Be Handled By Elderly Black Men. That way lies the grave, for the blues and just about everything else.”

While working on “Let Them Talk,” Laurie didn’t know if the album would succeed, but said in a YouTube video: “If it touches some people and leads (them) down the road that has given me so much pleasure in my life, then that will be a very great honor.”

Michael Shapiro writes about entertainment for The Press Democrat. Contact him at via his site: www.michaelshapiro.net

May 29, 2012

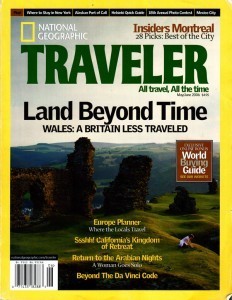

Somewhere Beyond Time: Jan Morris’s Wales in National Geographic Traveler

Jan Morris has been my mentor and a muse. When National Geographic Traveler asked me to travel to Wales to interview her and write about her corner of her beloved homeland, I leapt at the chance. I planned to meet Jan on my first day in Wales and have her set my itinerary, but she had other ideas.

The final version that appeared in NGT was trimmed slightly. One section that got cut was about a homey museum devoted to the Welshman David Lloyd George who steered Britain through one of its most difficult periods. Here’s the story, from the May/June 2006 issue of National Geographic Traveler:

By Michael Shapiro

“Come, I’d like to show you something,” says Jan Morris, the eminent Welsh author. We’re at the rustic Pen-y-Gwryd, a 200-year-old lodge clinging to the foothills of Mount Snowdon, Wales’ highest peak, where climbers Edmund Hillary, John Hunt, and others trained for 1953 Everest expedition. After a hearty lunch of steak pie and Guinness stout in the lodge’s Smoke Room, we walk under low ceilings past mullioned windows. The scent of wood smoke mingles with the aroma of fermented ales.

Look up, Morris says. Inscribed on the ceiling above us in thick black ink are the bold signatures of the climbers: E.P. Hillary, John Hunt, Charles Evans, and James Morris, then a reporter for the Times of London and the sole journalist on the 1953 Everest expedition. (Back then, Jan was called James, but we’ll get to that story later.) The climbers had returned to the lodge for reunions in the years after the famed 1953 expedition, the first to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain, and had left their marks on the lodge’s ceiling. Asked how high she’d climbed, Morris laughs and says, “It gets higher every year.” Thanks to Morris, who hustled down Everest the day the summit was reached and relayed an encoded message to the Times, news of this grand achievement reached Britain on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Look up, Morris says. Inscribed on the ceiling above us in thick black ink are the bold signatures of the climbers: E.P. Hillary, John Hunt, Charles Evans, and James Morris, then a reporter for the Times of London and the sole journalist on the 1953 Everest expedition. (Back then, Jan was called James, but we’ll get to that story later.) The climbers had returned to the lodge for reunions in the years after the famed 1953 expedition, the first to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain, and had left their marks on the lodge’s ceiling. Asked how high she’d climbed, Morris laughs and says, “It gets higher every year.” Thanks to Morris, who hustled down Everest the day the summit was reached and relayed an encoded message to the Times, news of this grand achievement reached Britain on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

I’d come to northwest Wales, to the region of Gwynedd, where Welsh is still widely spoken and where Welsh culture remains strong, to see Wales through Morris’s eyes. I hoped to trace Morris’s footsteps up Yr Wyddfa (the Welsh name for Mt. Snowdon, it means “grave of the giant”), to explore the imposing castles that ring the rugged Welsh coast, to see the great harbor town of Porthmadog and ride a 19th-century steam train to the slate quarries of Blaenau Ffestiniog, and to visit the whimsical Italianate village of Portmeirion, designed by Morris’s late friend, the architect Clough Williams-Ellis.

Most of all, I hoped that Morris could point me toward an understanding of how the tiny nation of Wales has survived – even thrived – with its language and culture intact, despite seven centuries of domination by England, its larger and more powerful neighbor to east. About the size of Massachusetts, Wales is a land of just 3 million people, surrounded by almost 60 million English, Irish, and Scots. Only about 200 miles long and as little as 40 miles wide, one can drive the length of Wales in less than a day and across it in a couple of hours.

* * *

Entering Wales by locomotive, I marvel at the mortarless stone walls and watch recently born lambs skip briskly across spring-green fields. Sheep, which have provided the Welsh with meat and wool for centuries, seem to cover almost every hillside and outnumber people in Wales by more than three to one. As the train heads up the west coast of Wales, tidy whitewashed houses dot the hills to the east and broad views of Cardigan Bay open to the West.

Embodying the warm hospitality of Wales, Morris has kindly invited me to visit her home in Llanystumdwy (the name means a holy place at a bend in the river) before our lunch at Pen-y-Gwryd. After rolling down the rutted driveway, Morris cuts the engine and I can hear the River Dwyfor sing sweetly nearby. Atop the thick-walled stone house is a creaky weathervane, a symbol of Jan’s dual Welsh and English ancestry: E and W mark east and west, G and D stand for Gogledd and De, the Welsh words for north and south.

Embodying the warm hospitality of Wales, Morris has kindly invited me to visit her home in Llanystumdwy (the name means a holy place at a bend in the river) before our lunch at Pen-y-Gwryd. After rolling down the rutted driveway, Morris cuts the engine and I can hear the River Dwyfor sing sweetly nearby. Atop the thick-walled stone house is a creaky weathervane, a symbol of Jan’s dual Welsh and English ancestry: E and W mark east and west, G and D stand for Gogledd and De, the Welsh words for north and south.

Morris, who turns 80 this year, has spent much of her life traveling, writing incisive books about Venice, Oxford, Sydney, Hong Kong, and Trieste, among other places. For the past several decades, she has always returned to this humble plot in remote northwestern Wales. In the early 1970s, Morris underwent a sex change operation and has since lived as a woman. She has remained with her partner Elizabeth, the mother of their four children, for more than 50 years.

We enter their home through an old stable door, which opens in upper and lower halves, and walk into a kitchen floored with Welsh slate. The next room is a long library with neatly organized bookshelves reaching from floor to ceiling. Upstairs over tea with Elizabeth, Jan, and their Norwegian forest cat, Ibsen, Morris and I get to talking.

“For me the essence of Wales is conflict,” she says. “It’s a constant struggle to keep Welsh culture alive” as more and more English families settle in Wales, bringing their habits with them. On the bright side, all Welsh schoolchildren today learn their mother tongue so knowledge of the Welsh language, one of Europe’s oldest, is on the rise. And though Wales remains part of the United Kingdom and is mostly governed from London, it recently formed its own national assembly.

“We have a nation-state,” Morris says. “I love the nation (of Wales) – it’s the state part of it I hate. I’m fed up with patriotism and nationality, but somehow we’ve got to preserve the culture,” she adds, noting that the Welsh word for Wales, Cymru, means comradeship. “I like the nature of Welsh civilization which is basically very kind, not ambitious or thrusting. It’s based upon things like poetry and music, which are still deeply rooted in this culture.” < note: Ok to cut these last 2 sentences are from A Sense of Place – or we could say these quotes came from ASOP.>

Before leaving I ask Morris about places to see and people to meet. She deftly sidesteps the question, but as we part she says, “Oh, you may want to look in on the Archdruid.” And then she bids me farewell with a wave and smile.

I find the Archdruid, Dr. Robyn Lewis, near the tiny town of Nefyn on the north coast of Wales’ Llyn peninsula. Lewis is the Archdruid of the National Eisteddfod, an annual cultural celebration dating to the 12th century that honors Wales’ top poets and prose authors. The weeklong festival, the most important cultural event in Wales, is filled with public performances of poetry and music, the arts that enliven the sometimes bleak Welsh days.

Somehow I imagine the Archdruid living in a low-slung cob hut surrounded by a circle of stones, but Lewis, who has lived in Nefyn since he was 3, resides in a contemporary home with sweeping views of the Llyn peninsula’s northern coastline. A stained-glass red dragon, the proud symbol of Wales, hangs in his front window, and hundreds of Welsh books line the walls. “I buy the Welsh books” to support local authors, Lewis says. “The English ones I get from the library.”

A distinguished author and retired judge, Lewis presided from 2002 to 2005 over the Gorsedd of Bards, a body composed of Wales’ literary lights responsible for the colorful Eisteddfod ceremony. Tall and lean but agile despite his advanced age, the bespectacled Lewis shows me an antique wooden chair almost as high as his ceiling, awarded to an Eisteddfod poetry winner in 1890. Lewis won the Eisteddfod award for prose in 1980, making him eligible to become an Archdruid. Three major awards are bestowed during the weeklong event: the literary medal is presented to the author of the best prose work; the crown goes to the composer of the best volume of poetry; and the great chair is awarded to the author of the best strict meter poem, a complex and distinctly Welsh type of poetry.

Rather than describe the Eisteddfod, Lewis plays a video of the 2003 ceremony, when Jan’s son Twm Morris (Twm, pronounced “Toom,” is Welsh for Tom) won the award for strict meter poetry. The silver-haired Archdruid, clad in a cream-colored robe with a golden breast plate and a sash emblazoned with red dragons, clasps a golden scepter and opens the proceedings. The bards file in wearing blue, green, or white robes and fill the stage. Two trumpeters sound a fanfare and the lights go down. Though Twm, seated in the audience, knows of his selection, the audience remains in the dark until a spotlight shines brilliantly on the winner. Twm stands, beaming, to receive his comrades’ wild cheers.

While Twm remains standing, the mistress of robes and four attendants in white nun-like attire proceed up the aisle to offer Twm his Eisteddfod robe. Unbeknownst to Twm, Lewis had arranged for Jan to serve as one of the attendants, and as she walks up the aisle Jan’s smile shines almost as brightly as the spotlight illuminating her son.

“Is there peace?” the Archdruid booms, adhering to tradition. “There is peace,” the audience responds. The Archdruid declares: “I now proclaim that Twm Morris has been chaired chief poet.” Twm takes his outsize chair as a young woman presents him with a horn of plenty and offers him the wine of welcome. A maiden offers a basket of flowers followed by a group of young girls dance. A massive sword, carried by a former rugby player (they’re the only ones strong enough to carry the sword, Lewis tells me) remains in its sheath, a symbol of peace. The ceremony closes with the national anthem. “That’s the Welsh anthem, ‘Land of our Fathers,’ not ‘God Save the Queen,’ ” Lewis says dryly as he switches off the video.

Like most Welsh citizens, Lewis is proud of his heritage. “You have one nation with 50 states – we have one state (the United Kingdom) with four nations (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales),” Lewis says. And, though most of Wales’ castles were built by English invaders, Lewis is proud of the citadels that fortify the Welsh coast: “We’re very rich in castles – that meant it was quite a job to keep us down.”

Though Morris is only half Welsh by birth, Lewis is unrestrained in praising her contributions to Wales. “She expresses her Welshness through English and that gets to the English establishment. If I express it, no one takes much notice,” he says. “I wouldn’t hesitate to call her a genius.”

I hop into my rented VW Passat, a big car by Welsh standards, and drive a few miles up the coast. From the narrow main road, I turn down a skinny lane that plunges almost vertically towards the shoreline. At the base of the hill is Nant Gwrtheyrn, the Welsh language institute and heritage center. Once a thriving quarry town, Nant Gwrtheyrn was abandoned in the 1950s. In the early ’70s squatters turned the low-slung L-shaped complex of stone buildings into a commune. It’s not hard to see why: with lush green fields and awe-inspiring views of the frothing surf, Nant Gwrtheyrn’s aesthetic glories complement its splendid isolation.

Philip Jenkins, a 35-year-old rock musician from the Welsh capital Cardiff, told me he’d been hoping to enroll at Nant Gwrtheyrn for years but had to save money. After receiving a scholarship for half the tuition, he came to the institute. Speaking Welsh isn’t a necessity, but Jenkins wanted to learn his mother tongue. “I like the sound; I like the rhythm,” he said. “It was in my family a century ago. We’re pushing back against homogenization. People are looking to their roots.”

These roots go back to Wales’ remote Celtic past. Welsh “has changed in essence so little down the centuries,” Morris writes in The Matter of Wales, “that an educated Welshman can still read, without too much difficulty, the Welsh of the Middle Ages.” Noting the language’s importance, Morris writes: “Without it, it can be said, there would be no Wales by now, only another province of England.” And in A Writer’s House in Wales, she says: “The very existence of Welsh, still defiant after so many centuries of alien pressure, is a magic in itself, and those with ears to hear find in its very cadences … a beauty akin to the music of the spheres.”

A few miles up the coast is Caernafon, the ancient walled city best known for its 13th-century castle. Built by King Edward I to quash ongoing Welsh rebellions against English occupation, the citadel juts like an iron fist into the Menai Strait. Composed of octagonal towers and serrated walls, the stronghold at Caernafon is a symbol of English dominion over Wales. Stone eagles, emblems of power, perch upon the castle’s battlements.

That evening I walk across the Afon Strait on the Aber bridge which rotates to let boats in and out of the harbor. A pair of white swans paddles through the inlet followed by five fluffy two-day-old chicks. “They were still in the egg Friday,” says Glyn Jones, a middle-aged man standing nearby. Gazing out at the lagoon, Jones extols the virtues of living in the Caernafon area: the easy pace, coastal fishing, neighborly warmth. But he laments that most young adults are heading to the capital, Cardiff, for work. English retirees and vacation-home buyers have driven up house prices in Wales, Jones says wistfully. “My friend’s daughter is a teacher and her husband is on the county council, but they can’t afford a mortgage.”

As darkness descends upon Caernafon, orange floodlights bathe the castle in a warm hue, softening its menacing facade. A swan flies so close I can hear the whoosh of its wings as seagulls squawk above. Two young men in Wellies climb into a rowboat — one doffs his cap as they motor under the bridge. The tide rises quickly, lifting a floating restaurant out of the tidal mud and providing a luminous reflecting pool for the castle. The ripples turn the castle’s reflection into a shimmering impressionist painting.

I drive on to Porthmadog, an old port town just seven miles from Morris’s home that serves as a convenient base for exploring her region of Wales. In the harbor, where a century ago tall-masted, slate-hauling ships were loaded round the clock, a few dozen pleasure craft bob up and down. I throw a windbreaker over my shoulders and walk along the Cob, an embankment crossing an estuary of the Glaslyn River. With views Mount Snowdon and its foothills, “This grand prospect is like an ideal landscape,” Morris writes in The Matter of Wales, “its central feature exquisitely framed, its balance exact, its horizontals and perpendiculars in splendid counterpoint. … It is the classic illumination of Wales.”

Morris’s book describes the remarkable skill of Welsh miners and quarrymen and the brutal hardships they faced. To see where they worked, I ride the Ffestiniog narrow-gauge rail that winds thirteen miles from Porthmadog to the slate quarries at Blaenau Ffestiniog. The four-car train is pulled along the two-foot-wide tracks by a 19th-century steam engine. Built in the 1830s to haul slate from the mountains to the coast, the Ffestiniog Railway is one Britain’s oldest railways.

During the trip’s first few miles we pass so close to people’s houses that I can see the photos on their nightstands. Next we ascend into woodlands graced with turquoise lakes. After the 75-minute ride to Blaenau Ffestiniog, we have just a few minutes to explore the old slate quarries – you can still see mountains of waste slate and the trails the men slid down at the end of their shifts.

The train’s driver, Paul Davies, rotates the engine for the return journey and invites me to ride up front with him. He tells me how the quarrymen would gather in “cabans,” typically small slate buildings, to play classical music, read poetry, and sing in choirs. “They may not have been formerly educated,” Davies says, “but the Welsh choirs were the stuff of legend.”

Back in Porthmadog, a television drama for Channel Four Wales is being filmed outside Y Llong (The Ship), a pub next to the hotel where I’m staying. The dialogue is in Welsh except for an expletive in English. “We don’t have any swear words – make love not war,” says Pat Hughes, the pub’s manager, as we watch the crew reshoot the scene. Pat tells me his countrymen had to protest to get a TV station that aired programs in Welsh. A Welshman named Gwynfor Evans went on a hunger strike in 1981 demanding the British government honor its promise to offer a Welsh-language TV channel, and Margaret Thatcher’s government caved. “The way we look at it, we’ve never been conquered,” Hughes says. “We’ve still got our language.”

A few miles down the road is the chimerical village of Portmeirion, designed by Welsh architect Clough Williams-Ellis, an old friend of Morris. Crowned by a belltower, the village, constructed from the 1920s through the 1970s to attract tourists, overlooks the estuary of the Dwyryd River. With buildings painted bright yellow, aquamarine, and terra cotta, Portmeirion is an uplifting contrast to the mostly colorless stone buildings of northern Wales. Morris calls it “a floating fantasy above the sea.” Portmeirion was the setting for the British cult drama “The Prisoner.” Soon after the short-lived series began airing in 1967, the number of visitors to Portmeirion jumped tenfold.

“It’s sort of a light opera approach to architecture,” says Robin Llywelyn, Clough’s grandson who serves as Portmeirion’s managing director. Llywelyn tells me his grandfather believed – like his half-Welsh colleague Frank Lloyd Wright – that architecture need not dominate the landscape; it could enhance it. “He never had a master plan,” Llywelyn says, which is clear from Portmeirion’s hodgepodge of styles and colors. But somehow this Willy Wonka-esque concoction of shops, villas, and cafés works, delighting young and old. Williams-Ellis was “always pleased to see kids enjoy it,” Llywelyn says. “Adults would want to know what it means. He’d say, ‘If I could have explained it in words, I wouldn’t have had to build it.’ ”

Beyond the village is a shady forest with trees imported from around the world and ponds dappled with lily pads. The fern-shrouded paths are brightened by magenta foxgloves. Coming around a bend, I stumble upon a dog cemetery; its heartfelt tributes – some in English, others in Welsh – are deeply moving. Says one little tombstone, “He gave us love, he gave us joy, he truly was, his father’s boy.”

Morris had mentioned that David Lloyd George, the Welshman who served as British Prime Minister from 1916 to 1922, grew up in her town, Llanystumdwy, so I returned there to visit the Lloyd George Museum. Located in the center of town, the museum honors this quintessentially Welsh leader: before he became prime minister Lloyd George fought for a “people’s budget” to ease the tax burden on the working class. In 1911 he proposed the National Insurance Act, laying the foundation for the social security reforms that transformed Britain during the 20th century. Taking power during the Great War, Lloyd George was hailed for leading Britain to victory, but his career deteriorated into acrimony over the partition of Ireland.

Part of the museum is the house where Lloyd George grew up with his uncle, a shoemaker. On a table are some old shoemaking tools – a photo of Abraham Lincoln hangs on one of the home’s thick stone walls. Iolo Wyn Edwards of the museum staff tells me that Lloyd George’s uncle admired Lincoln and imparted the American’s values to young Lloyd George, whose father had died when Lloyd George was just a year old. Just behind the museum, in the woods by the River Dwyfor, is Lloyd George’s grave. I enjoy a peaceful walk alongside the gently flowing river, the same stream that meanders by Morris’s home, until two military jets noisily slice the sky.

The last day of my trip, I awake to blue skies, a rarity in typically tenebrous Wales. I lace up my hiking boots and prepare to climb Mount Snowdon, Wales’ highest peak at 1085 meters. A mere foothill compared to the world’s great mountains, Snowdon offers a moderately challenging climb over rocky trails. I ascend the popular Pen-y-Gwryd track, a wide gravelly trail which begins steeply and then reaches a plateau with views of two deep blue lakes at the foot of a massif. After two hours of climbing, I approach Snowdon’s summit. At last I understand why Morris, who often writes of her “imagined” Wales, wouldn’t lay out my itinerary: She didn’t want to confine me to seeing her Wales. She wanted me to find my own.

From the empyrean summit of Snowdon I can see for miles and miles: to the west, the foothills bumping down to the Pen-y-Gwryd lodge; to the distant south, the bustling port town of Porthmadog; to the far north, the walled city of Caernafon and its citadel. The Llyn peninsula to the east is blanketed by clouds, but no matter: I can almost see the Archdruid in his Eisteddfod robes; I imagine Morris reading one of her son Twm’s poems in her library; I can envision young Lloyd George helping his uncle at his shoemaker’s workshop, hearing stories about a great egalitarian leader in a distant land called America.

Except for the first decade of the 1400s, the Welsh have lived under English rule for more than seven centuries. So many times the Welsh language and culture have seemed on the brink. With globalization and a cresting wave of English immigrants, the 21st century brings new threats to the rich heritage of Wales.

During my day with Morris I ask her if these are good times for Wales. “They’re better than they have been, but the more I think about it, the more concerned I become,” she says. “All we can do is keep smiling and keep fighting. We are always struggling.”

Morris raises the distinctly Welsh concept of hiraeth, an ineffable yearning. “We’re always longing for something,” she says, “but we’re not sure if it’s an ideal past or a better future.” Perhaps it’s this “perennial vision of a golden age, an age at once lost and still to come – a vision of another country almost, somewhere beyond time or even geography,” as Morris writes in The Matter of Wales, that gives the Welsh the strength and creativity to keep bucking the tide of history.

Michael Shapiro first met Jan Morris in 1992 at a travel writing seminar near San Francisco. “When I first met Jan she seemed like a visitor from another time,” Shapiro says. He interviewed Morris in Llanystumdwy for his book A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives, and Inspiration (Travelers’ Tales, 2004) which was briefly excerpted in National Geographic Traveler.

May 15, 2012

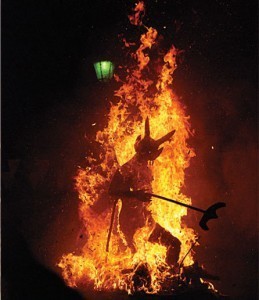

Burning the devil in Guatemala – American Way magazine

To spark the holiday season, Guatemalans roast an effigy of the devil. I wrote about the spectacle for American Way, AA’s inflight magazine. Here’s how the story starts:

To spark the holiday season, Guatemalans roast an effigy of the devil. I wrote about the spectacle for American Way, AA’s inflight magazine. Here’s how the story starts:

The flames rise 30 feet into the air, casting a lurid glow on spectators’ faces. The burning effigy gives off a villainous stench, its acrid smoke engulfing the plaza. Bomberos (firefighters) watch nervously as thousands of Guatemalans howl and rejoice, stamping their feet and jumping into the air to get a better view of the demise of el diablo.

Sparks drift toward the Esso station nearby; the conflagration illuminates a sign above the pumps that reads “No fumar.” It’s classic Guatemala: You can’t smoke, but you can soak a papier-mâché demon with gas and light it on fire.

May 8, 2012

River a Mile Deep: An unguided Grand Canyon rafting adventure, WorldHum

It’s not easy to find the right home for a 6,000-word story about rafting the Colorado River in the wake of John Wesley Powell. A civil war vet, Cpt. Powell and his party made the first descent of the Colorado through the Grand Canyon in 1869. Our trip was more planned and comfortable than Powell’s, but after a few days in the Canyon we started to have similar emotional reactions to being deep in the Canyon. This story has appeared in The Best Travel Writing 2011, published by Travelers’ Tales, and in the iPad zine Overnight Buses. On Worldhum it includes lots of evocative photos and three videos, the fullest treatment of the story. Click here to read the story on WorldHum.

Our boat captain, Owen Edwards, in the calm water as we drift toward Lava Falls.

.

River a Mile Deep: My Grand Canyon rafting adventure in WorldHum

It’s not easy to find the right home for a 6,000-word story about rafting the Colorado River in the wake of John Wesley Powell. A civil war vet, Cpt. Powell and his party made the first descent of the Colorado through the Grand Canyon in 1869. Our trip was more planned and comfortable than Powell’s, but after a few days in the Canyon we started to have similar emotional reactions to being deep in the Canyon. This story has appeared in The Best Travel Writing 2011, published by Travelers’ Tales, and in the iPad zine Overnight Buses. On Worldhum it includes lots of evocative photos and three videos, the fullest treatment of the story. Click here to read the story on WorldHum.

Our boat captain, Owen Edwards, in the calm water as we drift toward Lava Falls.

.

May 6, 2012

Frank Lloyd Wright’s humble experiment in Scottsdale, Ariz.

After seeing what FLW did with the Guggenheim, I expected his desert home to be outrageous and astonishing. Of course it wasn’t – the low-slung building fit perfectly with their desert surroundings. Following is my story on the witty and enormously talented architect, who showed flashes of ego throughout his life but who always knew how to design building that worked with their environs. For the story in the June 2o12 of Perceptive Travel, click here.

A HUMBLE PALACE:

Frank Lloyd Wright’s modest experiment in the Arizona desert

By Michael Shapiro

As a kid in New York, I was dazzled by the city’s soaring buildings: the towering Empire State, the wedge-like Flatiron, the art deco Chrysler with its menacing gargoyles. But the building that made perhaps the deepest impression was the Guggenheim Museum. On Fifth Avenue, across the street from Central Park, the museum’s architecture is like nothing else in New York. It doesn’t rise angular and mighty over the city and dominate the skyline; its rounded front, only a few stories above the street, seductively invites you in to explore its spiraling curves.

The Guggenheim’s design doesn’t so much shout, “Look, pay attention to me!” Rather, its confidence seems to say: “I know who I am and I don’t care what you think. I don’t have to fit in with the crowd.” When first seeing it, I felt a surge of curiosity, a sense that anything’s possible. I later learned that the Guggenheim’s first curator and director, Hilla Rebay, said to its architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, “I want a temple of spirit, a monument!

So on a recent trip to Arizona, celebrating the centennial of its statehood this year, I spent a day with Frank Lloyd Wright. Not literally of course – he died in 1959 at the age of 91 – but by visiting his home, Taliesin West, in Scottsdale and meeting with one of his students from the 1950s.

* * *

I set out from the Arizona Biltmore, where Wright’s art deco-esque blocks are a central design element, on a clear crisp March morning. From the Phoenix hotel, I drove about a half hour to see Taliesin West and to meet Arnold Roy, a student in Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship starting in 1952. The suburban sprawl gave way to gloriously open desert landscapes of muscular saguaros, graceful ocotillo and stout barrel cacti.

I didn’t expect anything palatial, but I thought I’d find structures among the saguaros that reflected Wright’s monumental ego. He famously said, in a 1957 interview with CBS’s Mike Wallace, “I’ve been accused of saying I was the greatest architect in the world, and if I’d said so I don’t think it would be very arrogant.” Then there’s the story, perhaps apocryphal, of Wright stating his occupation during a trial as “the world’s greatest living architect.” The judge asked how he could say such a thing. Wright’s reply: “I’m under oath.”

However the low-slung buildings on the 500-acre desert property are the epitome of humility, hugging the ground as part of the desertscape, seemingly not protruding from the land but receding into it. Just as the Guggenheim perfectly reflected the wildly experimental modern art of mid-century New York, Taliesin West ideally complements the tawny desert surrounding Wright’s home.

Perhaps his most earthy structure, the one that best highlights his ingenuity, is this refuge in the foothills of Arizona’s McDowell Mountains that served as his home for the last 22 years of his astonishingly productive life. Wright, whose mother’s ancestors came from Wales, named Taliesin after a 6th-century Welsh poet.

At Taliesin West, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, Wright created buildings that were “a grace to the landscape,” as he said, “rather than a disgrace.” He designed his buildings to grow “organically” out of the land and felt the built environment should be an extension of the natural world and a way to embrace our shared humanity.

Beginning in the mid-1930s when Arizona had been a state for less than a quarter century, Wright would travel each December from his home in Wisconsin to the then-remote Sonoran Desert outside Scottsdale. After Wright endured a bout with pneumonia in 1936, his wife Olgivanna urged him to spend winters in the salubrious desert climate. From 1937 on, the couple made annual migrations to his new home.

“I was struck by the beauty of the desert,” Wright said, “by the dry clear sun-drenched air, by the startling geometry of the mountains. The entire region was an inspiration and strong contrast to the pastoral landscape of our native Wisconsin. And out of that experience a revelation came for the design of these buildings.”

* * *

Lean, with a close-cropped white beard and lit up with the alacrity of a man who loves his work, Arnold Roy greeted me in one of the corridors that frame the land. Roy, now 80, still lives on the property and serves as an archivist for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

“I met Frank Lloyd Wright at the Plaza Hotel (in New York) while he was working on the Guggenheim,” Roy told me. “He said, ‘Go out West and we’ll try you out.’ That was the start of my architecture career.”

Like Wright’s other students during Taliesin’s early days, Roy spent his eight-year apprenticeship at Taliesin West in a canvas tent. It had been tent-dwelling students who’d built Taliesin’s 40,000 square feet from the ground up during the final two decades of Wright’s life.

“He was 70 years old when he came to Taliesin,” Roy said as we sipped tea. “There was nothing here, he was shy on cash, the apprentices were eager but that’s all you could say about them. And they built this place – by hand.”

Fellow architects derided Wright’s school as a Tom Sawyer-like scheme for extracting work from students and having them pay for the privilege. But Wright, inspired by Olgivanna, who had studied with the mystical teacher Gurdjieff, felt students learned by doing, and that they could absorb knowledge by being in the presence of a master.

Roy heartily agreed saying that just watching the fastidiously dressed Wright work was a lesson in itself. He said Wright could fully conceive a complex building before putting it to paper. And while Roy suggested that Wright enjoyed having admiring students around, he didn’t run the program for the money.

“I paid for that first year and Frank Lloyd Wright gave me seven years of scholarship. He was very generous,” Roy told me. But that didn’t mean Wright was forgiving or soft. He was “looking for people who were serious. If you didn’t pull your weight, he’d tell you to pack up right away.”

And though his students camped in the desert, Wright expected them to dress well for formal events such as recitals on the property. Wright’s acceptance letter to the fellowship told new students to bring “a sleeping bag and the tuxedo.”

* * *

To build the walls of much of Taliesin West, Wright employed “desert rubble masonry” composed of rocks found on the property, filled in with mortar made of local sand.

“That’s about as organic as you can get,” tour guide Char Burrows said later that day as we explored the property. “Frank Lloyd Wright was a green builder long before the term was ever applied to architecture.” The stones were called one-man or two-man rocks, she said, depending on how many people it took to lift them. The boulders used in the base of the walls were three-man rocks.

The desert rubble glowed golden in the afternoon sun as Burrows led a group of about 20 into Wright’s office and told us he completed a third of his 1100-plus commissions in the last decade of his life. He often said his religion was Nature, “with a capital N,” she said, and in Taliesin West’s early years Wright prohibited the use of glass windows, preferring canvas to soften the stark desert light.

Later, in a 2010 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, I read an essay by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, who studied under Wright. Taliesin’s fortress-like walls stood in sharp contrast to the airy, billowing textile ceilings, he said. When Wright began building his desert home, he had no heat, no plumbing and not much money. Pfeiffer writes that Taliesin’s living spaces reflect Wright’s limited budget, but “even when creating humble, camp-like spaces, Wright’s architectural genius is always evident.”

As our tour continued into a breezeway between buildings, two-foot triangles at the base of the roof cast diamond shadows on the walls and floor. “He called these ‘eye music’,” Burrows said, and believed the canvas tents and window coverings looked like sails on ship bobbing on a desert ocean. The view looks west toward Camelback Mountain – Wright was furious, Burrows said, when power poles were installed and marred his desert vista.

In the residential wing, which opened to the public in 2004, is Wright’s bedroom. It’s small, almost cramped, with Scandinavian furniture that looks as if it could have come from a mid-century Ikea. I found it surprising that this renowned architect had such a low-ceilinged bedroom, but Wright believed in “compression release” making some spaces small and others expansive to give the sensation of opening up into the natural world.

The Kiva Room, a place for ceremonies, has the feel of a sacred Native American chamber. With floor lights and recessed lighting, which Burrows said Wright invented, the Kiva Room stayed cool during the sweltering desert summers. In the music pavilion is a display of Froebel blocks, a childhood toy that inspired Wright’s love of geometry.

The sloping Cabaret Room, where films were shown and recitals held, is another display of Wright’s wizardly. It stays cool because it’s partly underground. Dinner was served on tables that folded down when the performance started and the acoustics were nearly perfect. The Wrights sat in back so they could overhear what guests up front were saying. “If they weren’t nice,” Burrows said, “they didn’t get invited back.”

There was Wright’s confidence with a dash of attitude. Yet Wright was humble enough to know he didn’t have all the answers, that his ideas shouldn’t be the last word. During Wright’s 22 years at Taliesin West, the modifications never stopped. Returning each winter, Pfeiffer said, Wright would make changes and say, “I’m seeing it with a fresh eye.”

Late in his life, Pfeiffer recalled, Wright said to his students “Boys, what I’ve done here is a charcoal sketch. It’s up to you to finish it when I’m gone.”

–

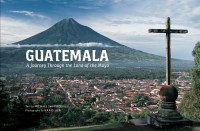

Michael Shapiro is author of “A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives, and Inspiration” and wrote the text for the pictorial book, “Guatemala: A Journey Through the Land of the Maya.” He has won the Travel Classics contest for best story about Arizona for the past three years. Contact him via www.michaelshapiro.net.

–

Sidebar on Arizona Biltmore: Many believe it was Frank Lloyd Wright who brought the Arizona Biltmore to the Southwest; in reality it was the Biltmore that lured Wright. The already famous architect traveled from the Midwest to Arizona in 1928 to consult, for a handsome fee of course, with his one-time apprentice draftsman, Albert Chase McArthur, on the design of the Biltmore.

McArthur wanted to use a version of Wright’s art deco-esque blocks, described by Wright’s wife, Olgivanna, as “abstracts inspired by cacti.”

McArthur believed – erroneously – that Wright had a patent on the design and offered to pay Wright $10,000, a prodigious sum back then, to use the textured blocks for the facade of the Biltmore. The venerable architect accepted the fee, never disabusing McArthur of the notion that he’d patented the blocks’ design.

–

IF YOU GO

Taliesin West celebrates its 75th anniversary as Arizona marks its centennial in 2012. Frank Lloyd Wright’s desert home will mark this milestone with programming ranging from symposiums and concerts to special events and enhanced tours. For updated information about programs and tours, held from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily. 12621 N Frank Lloyd Wright Blvd., Scottsdale, Ariz., 480-860-2700, www.franklloydwright.org.

The Arizona Biltmore, a Waldorf Astoria hotel, is one of Arizona’s first resorts and retains the mark of Frank Lloyd Wright. 2400 E. Missouri Ave., Phoenix, Ariz., 800-950-0086, www.arizonabiltmore.com.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Humble Desert Palace

After seeing what FLW did with the Guggenheim, I expected his desert home to be outrageous and astonishing. Of course it wasn’t – the low-slung building fit perfectly with their desert surroundings. Following is my story on the witty and enormously talented architect, who showed flashes of ego throughout his life but who always knew how to design building that worked with their environs. For the story in the June 2o12 of Perceptive Travel, click here.

A HUMBLE PALACE:

Frank Lloyd Wright’s modest experiment in the Arizona desert

By Michael Shapiro

As a kid in New York, I was dazzled by the city’s soaring buildings: the towering Empire State, the wedge-like Flatiron, the art deco Chrysler with its menacing gargoyles. But the building that made perhaps the deepest impression was the Guggenheim Museum. On Fifth Avenue, across the street from Central Park, the museum’s architecture is like nothing else in New York. It doesn’t rise angular and mighty over the city and dominate the skyline; its rounded front, only a few stories above the street, seductively invites you in to explore its spiraling curves.

The Guggenheim’s design doesn’t so much shout, “Look, pay attention to me!” Rather, its confidence seems to say: “I know who I am and I don’t care what you think. I don’t have to fit in with the crowd.” When first seeing it, I felt a surge of curiosity, a sense that anything’s possible. I later learned that the Guggenheim’s first curator and director, Hilla Rebay, said to its architect, Frank Lloyd Wright, “I want a temple of spirit, a monument!

So on a recent trip to Arizona, celebrating the centennial of its statehood this year, I spent a day with Frank Lloyd Wright. Not literally of course – he died in 1959 at the age of 91 – but by visiting his home, Taliesin West, in Scottsdale and meeting with one of his students from the 1950s.

* * *

I set out from the Arizona Biltmore, where Wright’s art deco-esque blocks are a central design element, on a clear crisp March morning. From the Phoenix hotel, I drove about a half hour to see Taliesin West and to meet Arnold Roy, a student in Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship starting in 1952. The suburban sprawl gave way to gloriously open desert landscapes of muscular saguaros, graceful ocotillo and stout barrel cacti.

I didn’t expect anything palatial, but I thought I’d find structures among the saguaros that reflected Wright’s monumental ego. He famously said, in a 1957 interview with CBS’s Mike Wallace, “I’ve been accused of saying I was the greatest architect in the world, and if I’d said so I don’t think it would be very arrogant.” Then there’s the story, perhaps apocryphal, of Wright stating his occupation during a trial as “the world’s greatest living architect.” The judge asked how he could say such a thing. Wright’s reply: “I’m under oath.”

However the low-slung buildings on the 500-acre desert property are the epitome of humility, hugging the ground as part of the desertscape, seemingly not protruding from the land but receding into it. Just as the Guggenheim perfectly reflected the wildly experimental modern art of mid-century New York, Taliesin West ideally complements the tawny desert surrounding Wright’s home.

Perhaps his most earthy structure, the one that best highlights his ingenuity, is this refuge in the foothills of Arizona’s McDowell Mountains that served as his home for the last 22 years of his astonishingly productive life. Wright, whose mother’s ancestors came from Wales, named Taliesin after a 6th-century Welsh poet.

At Taliesin West, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, Wright created buildings that were “a grace to the landscape,” as he said, “rather than a disgrace.” He designed his buildings to grow “organically” out of the land and felt the built environment should be an extension of the natural world and a way to embrace our shared humanity.

Beginning in the mid-1930s when Arizona had been a state for less than a quarter century, Wright would travel each December from his home in Wisconsin to the then-remote Sonoran Desert outside Scottsdale. After Wright endured a bout with pneumonia in 1936, his wife Olgivanna urged him to spend winters in the salubrious desert climate. From 1937 on, the couple made annual migrations to his new home.

“I was struck by the beauty of the desert,” Wright said, “by the dry clear sun-drenched air, by the startling geometry of the mountains. The entire region was an inspiration and strong contrast to the pastoral landscape of our native Wisconsin. And out of that experience a revelation came for the design of these buildings.”

* * *

Lean, with a close-cropped white beard and lit up with the alacrity of a man who loves his work, Arnold Roy greeted me in one of the corridors that frame the land. Roy, now 80, still lives on the property and serves as an archivist for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

“I met Frank Lloyd Wright at the Plaza Hotel (in New York) while he was working on the Guggenheim,” Roy told me. “He said, ‘Go out West and we’ll try you out.’ That was the start of my architecture career.”

Like Wright’s other students during Taliesin’s early days, Roy spent his eight-year apprenticeship at Taliesin West in a canvas tent. It had been tent-dwelling students who’d built Taliesin’s 40,000 square feet from the ground up during the final two decades of Wright’s life.

“He was 70 years old when he came to Taliesin,” Roy said as we sipped tea. “There was nothing here, he was shy on cash, the apprentices were eager but that’s all you could say about them. And they built this place – by hand.”

Fellow architects derided Wright’s school as a Tom Sawyer-like scheme for extracting work from students and having them pay for the privilege. But Wright, inspired by Olgivanna, who had studied with the mystical teacher Gurdjieff, felt students learned by doing, and that they could absorb knowledge by being in the presence of a master.

Roy heartily agreed saying that just watching the fastidiously dressed Wright work was a lesson in itself. He said Wright could fully conceive a complex building before putting it to paper. And while Roy suggested that Wright enjoyed having admiring students around, he didn’t run the program for the money.

“I paid for that first year and Frank Lloyd Wright gave me seven years of scholarship. He was very generous,” Roy told me. But that didn’t mean Wright was forgiving or soft. He was “looking for people who were serious. If you didn’t pull your weight, he’d tell you to pack up right away.”

And though his students camped in the desert, Wright expected them to dress well for formal events such as recitals on the property. Wright’s acceptance letter to the fellowship told new students to bring “a sleeping bag and the tuxedo.”

* * *

To build the walls of much of Taliesin West, Wright employed “desert rubble masonry” composed of rocks found on the property, filled in with mortar made of local sand.

“That’s about as organic as you can get,” tour guide Char Burrows said later that day as we explored the property. “Frank Lloyd Wright was a green builder long before the term was ever applied to architecture.” The stones were called one-man or two-man rocks, she said, depending on how many people it took to lift them. The boulders used in the base of the walls were three-man rocks.

The desert rubble glowed golden in the afternoon sun as Burrows led a group of about 20 into Wright’s office and told us he completed a third of his 1100-plus commissions in the last decade of his life. He often said his religion was Nature, “with a capital N,” she said, and in Taliesin West’s early years Wright prohibited the use of glass windows, preferring canvas to soften the stark desert light.

Later, in a 2010 issue of the Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly, I read an essay by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, who studied under Wright. Taliesin’s fortress-like walls stood in sharp contrast to the airy, billowing textile ceilings, he said. When Wright began building his desert home, he had no heat, no plumbing and not much money. Pfeiffer writes that Taliesin’s living spaces reflect Wright’s limited budget, but “even when creating humble, camp-like spaces, Wright’s architectural genius is always evident.”

As our tour continued into a breezeway between buildings, two-foot triangles at the base of the roof cast diamond shadows on the walls and floor. “He called these ‘eye music’,” Burrows said, and believed the canvas tents and window coverings looked like sails on ship bobbing on a desert ocean. The view looks west toward Camelback Mountain – Wright was furious, Burrows said, when power poles were installed and marred his desert vista.

In the residential wing, which opened to the public in 2004, is Wright’s bedroom. It’s small, almost cramped, with Scandinavian furniture that looks as if it could have come from a mid-century Ikea. I found it surprising that this renowned architect had such a low-ceilinged bedroom, but Wright believed in “compression release” making some spaces small and others expansive to give the sensation of opening up into the natural world.

The Kiva Room, a place for ceremonies, has the feel of a sacred Native American chamber. With floor lights and recessed lighting, which Burrows said Wright invented, the Kiva Room stayed cool during the sweltering desert summers. In the music pavilion is a display of Froebel blocks, a childhood toy that inspired Wright’s love of geometry.

The sloping Cabaret Room, where films were shown and recitals held, is another display of Wright’s wizardly. It stays cool because it’s partly underground. Dinner was served on tables that folded down when the performance started and the acoustics were nearly perfect. The Wrights sat in back so they could overhear what guests up front were saying. “If they weren’t nice,” Burrows said, “they didn’t get invited back.”

There was Wright’s confidence with a dash of attitude. Yet Wright was humble enough to know he didn’t have all the answers, that his ideas shouldn’t be the last word. During Wright’s 22 years at Taliesin West, the modifications never stopped. Returning each winter, Pfeiffer said, Wright would make changes and say, “I’m seeing it with a fresh eye.”

Late in his life, Pfeiffer recalled, Wright said to his students “Boys, what I’ve done here is a charcoal sketch. It’s up to you to finish it when I’m gone.”

–

Michael Shapiro is author of “A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives, and Inspiration” and wrote the text for the pictorial book, “Guatemala: A Journey Through the Land of the Maya.” He has won the Travel Classics contest for best story about Arizona for the past three years. Contact him via www.michaelshapiro.net.

–

Sidebar on Arizona Biltmore: Many believe it was Frank Lloyd Wright who brought the Arizona Biltmore to the Southwest; in reality it was the Biltmore that lured Wright. The already famous architect traveled from the Midwest to Arizona in 1928 to consult, for a handsome fee of course, with his one-time apprentice draftsman, Albert Chase McArthur, on the design of the Biltmore.

McArthur wanted to use a version of Wright’s art deco-esque blocks, described by Wright’s wife, Olgivanna, as “abstracts inspired by cacti.”

McArthur believed – erroneously – that Wright had a patent on the design and offered to pay Wright $10,000, a prodigious sum back then, to use the textured blocks for the facade of the Biltmore. The venerable architect accepted the fee, never disabusing McArthur of the notion that he’d patented the blocks’ design.

–

IF YOU GO

Taliesin West celebrates its 75th anniversary as Arizona marks its centennial in 2012. Frank Lloyd Wright’s desert home will mark this milestone with programming ranging from symposiums and concerts to special events and enhanced tours. For updated information about programs and tours, held from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. daily. 12621 N Frank Lloyd Wright Blvd., Scottsdale, Ariz., 480-860-2700, www.franklloydwright.org.

The Arizona Biltmore, a Waldorf Astoria hotel, is one of Arizona’s first resorts and retains the mark of Frank Lloyd Wright. 2400 E. Missouri Ave., Phoenix, Ariz., 800-950-0086, www.arizonabiltmore.com.

May 1, 2012

Hugh Laurie’s in the house: concert preview for The Press Democrat

Usually when an actor takes the stage to play music it’s mediocre at best. But Hugh Laurie can really play piano and has assembled a top-shelf band from New Orleans. I profiled Laurie in advance of last Tuesday’s show in Napa, which was superb. Here’s my story from The Press Democrat, below:

Hugh Laurie plays guitar and piano, and sings standards with his New Orleans blues band.

Hugh Laurie is in the house

By Michael Shapiro

The Press Democrat

Wednesday, May 23, 2012

After listening to British actor Hugh Laurie’s rollicking album “Let Them Talk,” a gumbo of New Orleans blues styles, one has to ask: What can’t Laurie do?

You know him as the acerbic diagnostician, Dr. House, on the TV show “House.” And you may have sensed he could play piano during those snippets of the show when Laurie taps the keys.

But did you know Laurie was a champion rower in his youth? His father was an Olympic gold-medal-winning oarsman, and Laurie was on track for the Games before mononucleosis laid him low.

While a member of the Cambridge Footlights, an amateur acting troupe that has launched many careers, Laurie met and dated actress Emma Thompson. They remain good friends.

He then turned his talents to sketch comedy, gaining fame as half of the Fry and Laurie team with his close friend Stephen Fry.

The release of “Let Them Talk,” with guest musicians including soul singer Irma Thomas, keyboardist Dr. John and Welsh vocalist Tom Jones, puts Laurie on the musical map. Listening to the album is like a steamy stroll through the French Quarter on a sweltering summer night.

“Let Them Talk,” released last year, has reached the top of the Billboard blues chart and is a Gold record in the U.K. Laurie’s piano-playing has garnered favorable reviews, though there are moments when his voice sounds thin and reedy.

On the PBS show “Great Performances” Laurie, who has battled depression, said he’s drawn to the blues because the music evokes feeling.

“Blues can bring out in me every single human emotion,” Laurie said, “or at least every emotion that I know of. ‘Let Them Talk’ is an odyssey — my destination is the holy city of New Orleans.”

Laurie plays piano on “After You’ve Gone,” sung by his longtime hero, Dr. John, a highlight of the album.

“I played the piano for Dr. John — I can’t believe I’m saying that sentence,” Laurie said on the PBS show. “I’ve worshiped Dr. John, I mean really worshiped Dr. John, for as long as I can remember, and for me to be actually playing while he sings … I left the studio that day and I got into my car and actually wept.”

It wasn’t just Laurie’s appreciation of Dr. John, however, that led him to play piano.

“I tended to favor the piano over the guitar because it stays in one place, which is what I like to do,” he says on his website. “Guitars appeal to the footloose, the restless. I like sitting a lot.”

So what’s a British actor — don’t be fooled by the American accent he uses on “House” — doing headlining an album of New Orleans blues classics?

“I was not born in Alabama in the 1890s. You may as well know this now,” writes Laurie, 52, on the album’s website. “I’ve never eaten grits, cropped a share, or ridden a boxcar. … Let this record show that I am a white, middle-class Englishman, openly trespassing on the music and myth of the American south.”

He goes on: “If that weren’t bad enough, I’m also an actor: one of those pampered ninnies who hasn’t bought a loaf of bread in a decade and can’t find his way through an airport without a babysitter.

“Worst of all, I’ve broken a cardinal rule of art, music, and career paths,” he says. “Actors are supposed to act, and musicians are supposed to music. That’s how it works. You don’t buy fish from a dentist, or ask a plumber for financial advice.

So why listen to an actor’s music?

His simple answer: he loves the blues with all his heart, provenance be damned.

“The blues have made me laugh, weep, dance. New Orleans was my Jerusalem,” he says, noting that the music fills him up.

“I could never bear to see this music confined to a glass cabinet, under the heading Culture: Only To Be Handled By Elderly Black Men. That way lies the grave, for the blues and just about everything else.”

While working on “Let Them Talk,” Laurie didn’t know if the album would succeed, but said in a YouTube video: “If it touches some people and leads (them) down the road that has given me so much pleasure in my life, then that will be a very great honor.”

Michael Shapiro writes about entertainment for The Press Democrat. Contact him at via his site: www.michaelshapiro.net

Michael Shapiro's Blog

- Michael Shapiro's profile

- 3 followers