Michael Shapiro's Blog, page 13

April 25, 2012

Anne Lamott on her baby having a baby

When my book A Sense of Place came out a few years ago I got compliments about being a good interviewer. But here’s the secret: I interviewed people — the world’s leading travel writers — who had something to say. I had a similarly delightful experience interviewing author Anne Lamott who recently published Some Assembly Required about her son Sam and his girlfriend having a baby when Sam is 19.

When my book A Sense of Place came out a few years ago I got compliments about being a good interviewer. But here’s the secret: I interviewed people — the world’s leading travel writers — who had something to say. I had a similarly delightful experience interviewing author Anne Lamott who recently published Some Assembly Required about her son Sam and his girlfriend having a baby when Sam is 19.

Here’s a link to my conversation with Annie as well as the full text of the story below.

Lamott on Letting Go

By Michael Shapiro

In 1993, Marin author Anne Lamott published “Operating Instructions,” a painfully honest account of the joys — and the trials — of single motherhood. Less than two decades after that book about her son’s first year, 19-year-old Sam announced that he and his girlfriend Amy were pregnant and intended to have the baby.

Lamott, whose devotion to keeping a journal began partly as a way to seek equilibrium in a tumultuous world, wrote extensively throughout her grandson’s first year.

In a phone conversation earlier this month, Lamott said, “My editor asked me if I would consider doing a sequel, writing about Sam and his new baby. I said, ‘Well, I think that would be exploitive,’ and the editor said, ‘Not if you didn’t exploit anyone.’”

She asked her son about creating a book together, she said, and “Sam loved the idea. His energy was really what got this book to happen.”

In keeping with Lamott’s other non-fiction books, “Some Assembly Required: A Journal of My Son’s First Son,” is comprised of lightly edited journal entries.

Much of the material is in its raw form or close to it, Lamott says. The editing is mostly shaping.

“You have to cut away your precious prose and find the core, the kernel that resonates,” she said. “It’s kind of like a treasure hunt.”

The book is filled with treasure; the insights from this seasoned writer can make readers laugh and cry on the same page. And Sam emerges as a remarkably self-aware young man in the email “interviews” with his mother.

He writes that “with Jax’s birth, Samland (where he lived as a free and independent teenager before the birth of his son) has been permanently breached. … Now it’s Sam-and-Jaxland.”

“We as parents have the illusions that we make our kids stronger, but they make us stronger,” he writes. That’s a remarkable insight for a college student who’s struggling to do his homework, salvage his relationship with his girlfriend and provide for his child. All before he’s old enough to legally drink.

Fortunately, he doesn’t turn to the bottle to cope; like his mother, he finds salvation in faith: “Sometimes when you’re a parent you’re hanging on by a pinkie finger, and you say to God, ‘Trusting you, Dude — I trust you have a plan for us.’”

That sounds a lot like a sentence Lamott might have written in “Operating Instructions,” until Sam refers to God as “Dude.”

Lamott appears Thursday in Sebastopol for an hour-long talk followed by a Q and A. She said she hopes Sam attends, too, but she’s not sure he’ll have time since they will just be returning from a tour together.

When Sam initially told Lamott he was going to be a father, her heart dropped as she realized his life would become “infinitely harder.”

But then she got excited about being a grandmother. After the baby was born, Lamott fell head-over-heels in love, but to her chagrin realized that grandparents are not in charge of much.

She writes about trying to accept that, and how it’s one more way she’s not fully in control of her life.

“Letting go is just not my strong suit,” she said. “There’s an old saying that everything we let go of has claw marks on it, and that was doubly true after I had a grandchild. You just have to let go thinking that it’s in any way your child or your business.

“And that just drove me crazy because I think I’m so old and wise, I’ve lived so much life. It’s their kid, but I just think I have such GOOD IDEAS in capital letters. It can make you have a crazy awful life if you let it.”

There’s abundant humor in “Some Assembly.” When Sam and Amy leave Jax with a babysitter instead of with her, a huffy Lamott writes: “I guess they just don’t care about the baby anymore. Otherwise they would have left him with me.”

Perhaps the ultimate challenge during her grandson’s first year was coming to terms with the deeper vulnerability she feels, a result of her bottomless love for the new member of her family.

She recalls years before hearing about the death of a grandson and saying how horribly sad that must be for parents. When Lamott became a grandmother, she realized she overlooked how endlessly painful the loss must have been for the grandparents as well.

“The thing about grandchildren is that they’re just like meat tenderizer; you’re so undefended against the love of a grandchild,” Lamott said.

“And yet that’s why we’re here, to open and soften. Grandkids are really grad school in being vulnerable.”

Michael Shapiro writes about entertainment for The Press Democrat. Contact: michaelshapiro@pressdemocrat.com.

March 26, 2012

Lily Tomlin rocks the house

These days Lily Tomlin’s character Ernestine, the gossipy telephone operator who used to parody the AT&T monopoly, works for an insurance firm, “denying health care to everybody.” She told me this during a phone interview in March, 2012, for a Press Democrat story. Tomlin was warm, funny and genuine in our conversation, just as she is on stage. For the full story, click here, or see the text below:

These days Lily Tomlin’s character Ernestine, the gossipy telephone operator who used to parody the AT&T monopoly, works for an insurance firm, “denying health care to everybody.” She told me this during a phone interview in March, 2012, for a Press Democrat story. Tomlin was warm, funny and genuine in our conversation, just as she is on stage. For the full story, click here, or see the text below:

By MICHAEL SHAPIRO

THE PRESS DEMOCRAT

Lily Tomlin hasn’t stopped taking shots at targets she feels deserve it. Remember her character Ernestine, the gossipy telephone operator who used to parody the AT&T monopoly by saying “We don’t care, we don’t have to; we’re the phone company.”

Today Ernestine works for an insurance firm, “denying health care to everybody,” Tomlin said during a phone interview this month from her home in Los Angeles.

And she fired away at recent Republican candidates for president.

Michelle Bachman said she attended Oral Roberts University after God told her to go to law school. This led Tomlin to quip: “Don’t you think if God told you to go to law school he’d have told you to go to Harvard?”

Tomlin said she’s not trying to make it personal.

“You’re not just going to take a flat-on cranial shot at somebody,” she said. The goal is “not to destroy them as an individual but kind of what they represent and how that impacts on our lives.”

But here’s the thing: whether or not you agree with Tomlin’s liberal politics, it’s hard not to like her, especially when seeing her live.

She has a knack for getting people on her side. When she winks or nods or gives you a deadpan look or sly smile, you feel like she’s connecting just with you.

“I talk about all of us on Spaceship Earth together trying to hack it,” she said. “I feel like we’re in the bomb shelter. We want to laugh in some way – we don’t want to sit there and be in misery. We’re all in this together.”

Tomlin, who grew up in a working-class neighborhood in Detroit, got an early break when she joined the comedy variety show, “Laugh-in,” in 1969.

That’s where she created Ernestine and the whip-smart little girl Edith Ann, who’d sit in a gigantic chair and often end her bits by saying “And that’s the truth!”

Her characters remain a key element of her 90-minute show, which she’ll bring to Santa Rosa’s Wells Fargo Center tomorrow night . There won’t be any huge chairs on stage, but Tomlin will play the characters with voice and body language, and there will be film clips of the characters on screen.

Tomlin, whom Time magazine once called “the woman with the kaleidoscopic face,” converses with her characters in an ongoing dialogue as the show progresses. She plans to allow time for a question-and-answer at the end of the show.

Tomlin’s resume ranges from Robert Altman classics like “Nashville” to 1980’s wildly popular “Nine to Five” with Dolly Parton and Jane Fonda.

More recently, Tomlin, 72, has appeared in “The West Wing,” “Desperate Housewives” and “Damages.”

She’s won four Emmy awards, two Peabody awards for her TV work, and a Grammy for a comedy album.

But it’s in front of an audience that she feels most alive. “Just the intimacy and being in a house in that moment with those people and somehow making it work on the stage,” she said.

She develops her shows with her life partner, the writer Jane Wagner, but she’s frustrated about Wagner not getting enough credit for her writing.

One line from the Wagner-penned show, “The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe,” is often used by Ted Koppel, who credits Tomlin for saying: “No matter how cynical you become, it’s never enough to keep up.”

Tomlin has contacted Koppel and asked him to credit Wagner, but she says it’s no use.

Asked if it’s a challenge to work so closely with her life partner, Tomlin said, “Of course it is – we overlap tremendously; that’s why we’re so close.”

They’ve been together since the 1970s when Tomlin lured Wagner to the West coast to help her produce a comedy album.

“I was crazy about her, and I was trying to get to live on the same coast because I wanted to be with her,” Tomlin said. “She was a little harder to get than I was.”

Though Tomlin doesn’t miss George W. Bush’s presidency, she does miss him as a comic target.

Back in 2004 she had some consoling words for him: Tomlin’s Ernestine called him and said: “You don’t have to worry about Senator Kerry – he just served in a war; you actually started one.”

March 3, 2012

Ballad of Pat Tillman, Metro newspapers

The football star–turned–soldier became the Pentagon’s poster boy, and when he was shot dead by U.S. Army Rangers, the military said he was killed by enemy fire. The deception, it turns out, was not an isolated incident, but part of a pattern of keeping the truth from the families of war casualties. I wrote this story in 2007 but the pattern persists to this day. The full 5,000-word story is below, or click here to read it at Metro’s site.

–

‘CEASE FIRE. Friendlies! I am Pat fucking Tillman, dammit,” shouted former pro football player turned Army Ranger Pat Tillman as a hail of bullets pierced the darkening Afghani sky. “CEASE FIRE! FRIENDLIES! I AM PAT FUCKING TILLMAN! I AM PAT FUCKING TILLMAN!”

On patrol in eastern Afghanistan at dusk on April 22, 2004, Tillman and his men hit the dirt, trying to escape swarms of artillery fire coming from the valley below. Tillman detonated a smoke bomb, hoping to signal to his comrades that they were shooting at U.S. troops, known in military parlance as “friendlies.” The firing stopped.

After a moment, Tillman, probably assuming he’d been recognized, stood up. Another barrage of bullets rocketed across the dusty canyon. Three of those bullets shattered Tillman’s skull, ending his life. Other bullets hit his body, with some of the shrapnel becoming embedded in his body armor. An Afghani soldier allied with U.S. forces was also killed, and two other soldiers were injured.

Tillman, lauded by military and government leaders for giving up a multimillion-dollar pro football contract, was America’s best known soldier. A San Jose native, Tillman grew up in the Almaden neighborhood and was a stand-out football player at Leland High School. He became the Pac-10 defensive player of the year at Arizona State University and then went pro with the NFL’s Arizona Cardinals.

Even before his death, Tillman was considered a model of self-sacrifice, integrity and decency, not just for his commitment to his country, but for his honesty, candor and conscientiousness. Which makes what the U.S. military told Tillman’s family about Pat’s death that much more appalling.

Tillman’s brother, Kevin Tillman, was part of the same 75th Ranger Regiment that Pat served, but the soldiers in his unit didn’t tell him how his brother died. Rangers were ordered not to say a word about the actual circumstances of his death.

“Immediately after Pat’s death, our family was told that he was shot in the head by the enemy in a fierce firefight outside a narrow canyon,” Kevin Tillman told the Congressional Committee on Oversight and Government Reform during a hearing April 24 entitled “Misleading Information from the Battlefield.”

Reading from his brother’s Silver Star citation, referred to in an April 30 internal Pentagon email as the “Tillman SS gameplan,” Kevin Tillman provided an abridged version of what the military said about his brother’s death: “Above the din of battle, Corporal Tillman was heard issuing fire commands to take the fight to an enemy on the dominating high ground. Always leading from the front, Corporal Tillman aggressively maneuvered his team against the enemy position on a steep slope. As a result of Corporal Tillman’s effort and heroic action … the platoon was able to maneuver through the ambush position … without suffering a single casualty,” Kevin Tillman stated at the hearing.

“This story inspired countless Americans, as intended,” but “there was one small problem with the narrative,” Tillman told the Congressional Oversight panel. “It was utter fiction.”

A Construction Of Lies

Kevin Tillman doesn’t believe the errors were “missteps” as stated in the Army Investigator General’s report, which was released in late March and is the most recent of several official inquiries into Pat Tillman’s shooting and its aftermath. The probes, all done by military investigators, have looked into the circumstances of Tillman’s death as well as the false statements about it.

“A terrible tragedy that might have further undermined support for the war in Iraq,” Kevin Tillman said, “was transformed into an inspirational message that served instead to support the … wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.”

Rep. Henry Waxman (D–Los Angeles), chair of the Congressional Oversight committee, said at the hearing: “The bare minimum we owe our soldiers and their families is the truth. That didn’t happen for the two most famous soldiers in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. For Jessica Lynch and Pat Tillman, the government violated its most basic responsibility. Sensational details and stories were invented in both cases.”

Waxman noted that “news of [Tillman's] fratricide flew up the chain of command within days, but the Tillman family was kept in the dark for more than a month. Military officials sat in silence during a nationally televised memorial ceremony highlighting Pat Tillman’s fight against the terrorists. Evidence was destroyed and witness statements were doctored. The Tillman family wants to know how all of this could have happened. And they want to know whether these actions were all just accidents or whether they were deliberate.”

Norman Solomon, author of the book War Made Easy, agrees with the Tillman family that Pat was used to promote the wars. “This was a perfect storm of idolatry from the Pentagon standpoint: a football hero sacrificing himself for patriotic reasons—it was central casting as far as the Rumsfeld gang was concerned,” he said. “The mythology was so wonderful that the facts were inconvenient and unnecessary.”

What’s astonishing is not just the lengths the Army went to create a fictional account, which included changing the testimony of soldiers who witnessed the friendly fire shooting and the destruction of evidence such as the burning of Tillman’s blood–stained uniform. It’s that this was not an isolated incident but rather part of a pattern of deception.

In recent months, several other families have pressed the military for details about their loved ones’ deaths, uncovering similar fabrications. These revelations, coming to light after soldiers’ relatives demanded details about their family members’ final hours, may represent a fraction of the military’s effort to conceal friendly fire or accidental deaths and injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan.

At the April 24 Congressional Oversight hearing, Lynch, portrayed in spring 2003 as the “little girl Rambo from the hills of West Virginia who went down fighting,” testified that the story the military told about her was a blatant lie. Lynch never fired a shot when her caravan was ambushed. After being severely wounded, she was kept alive by Iraqi doctors and nurses, who donated their own blood to keep Lynch alive.

Most shocking: according to sworn testimony during the Oversight Committee’s hearing, Lynch’s “rescue” from the Iraqi hospital was delayed by a day so that the Army could bring in camera crews. After stating Lynch was being held by hostile forces, the military waited 24 hours to rescue her so they could make a propaganda film.

Three South Bay Families Deceived

Suggesting the potentially broad scope of the military’s deception: Tillman was just one of three soldiers with South Bay (San Jose and Silicon Valley) roots killed in Iraq or Afghanistan during a two–month period whose families were lied to about their deaths.

Mountain View resident Karen Meredith lost her only child, Lt. Ken Ballard, on May 30, 2004, just days after the military disclosed that Tillman had died from friendly fire. Speaking at Ballard’s memorial service, an officer said Ballard’s heroics saved the lives of 60 men. Ballard was awarded the Bronze Star.

“The officer said how Ken fought and fought and fought to cover for two platoons so they could get back to base,” Meredith said. “Given his heroism, I questioned why Ken was not given the Silver Star [a higher honor than the bronze star]. He said the Silver Star was very rare. I didn’t trust them, but I was still grieving and thought I’d have time to think about that later. I vowed that Ken would get every award he deserved, so I started asking for the incident report.”

Fifteen months after Meredith’s son died, Lt. Col. John O’Brien, the head of the Army casualty division, visited her at her home. O’Brien told her that Ballard was killed by an accidental discharge of the unmanned M-240 machine gun on his tank.

“My life was in upheaval—I believed what I believed for 15 months,” Meredith said. “My heart was ripped open again.”

Nadia McCaffrey, whose son Patrick McCaffrey worked as a manager at a Palo Alto automotive shop, said she was told that her son, a member of the National Guard, was shot and killed by insurgents in an ambush. Patrick McCaffrey, 34, the father of two young children, died near Balad, Iraq, on June 22, 2004. It was two years later, Nadia said, that she learned her son was murdered by three Iraqis, including two Iraqi civil defense force soldiers McCaffrey was training.

Yet it was Pat Tillman’s tale that riveted the nation. Tillman was the essence of the young, idealistic and intelligent American. Strong in mind and body, a maverick who was willing to make the ultimate sacrifice, placing concern for his fellow Rangers above his own safety, Tillman was a loyal son, brother and husband. And he was a football star with rugged good looks. It’s no accident that he became, against his wishes, the poster boy for the Bush Administration’s wars.

Defying Gravity

Mary Tillman, a teacher at an Almaden (south San Jose) middle school, said her son Pat joined the Army because “the country was in danger, the country was in need, and football seemed trivial.” In a telephone interview with Metro Silicon Valley, she said her son believed in shared sacrifice and that the military should be made up of people all across society, not just those who needed a job.

“It was also an experience,” she added, saying Tillman was always seeking the exhilaration and understanding that came from placing himself in novel, uncomfortable or challenging situations. And, she said, he always sought to live passionately.

For Tillman, the football field was a place where he could express his exuberance. Paul Yllana, assistant principal at Leland High School, played football with Tillman at Leland in the early 1990s. Yllana said Tillman was the best player on the team and the key to its 1993 Central Coast championship.

“He was selfless even at 14 years old. He credited his teammates, coaches, he never took credit. He was our captain, our leader, the guy we followed,” Yllana said. “His emotion and drive fueled the rest of the team. I already saw his sense of commitment in high school: He worked harder and longer than anyone else, and he enjoyed it.”

Tillman had an “intense, emotional approach to the game,” Yllana said. Not only was he the defensive star, he was one of the team’s running backs. “He wasn’t physically enormous, but he could see and react so much faster than everybody else. He had incredible vision for a high school athlete.”

Yllana played running back in practice once: “I was a pretty good-sized guy—200 pounds in high school—and I see Tillman accelerating towards me. He had incredible closing speed,” Yllana said. “I’ve never been hit that hard in my life.”

Despite Tillman’s accomplishments in high school football, Yllana said most colleges weren’t interested in the “undersized” player (Tillman was 5–foot–11). “ASU took a chance and gave him their last scholarship, and he became Pac–10 defensive player of the year.”

But Tillman never let his commitment to football interfere with his pursuit of knowledge. He graduated from ASU in three and a half years with a 3.84 grade point average (virtually a straight–A student). The Arizona Cardinals selected Tillman with a seventh-round pick, making him the 227th player drafted.

“They gave him a shot because he’d played for ASU and was a ‘hometown kid,’” Yllana said. But it was a long shot; few seventh–rounders establish themselves in the NFL. After defying the odds and becoming one of the league’s better safeties, Tillman was offered a five-year, $9 million contract from the St. Louis Rams. He turned it down to remain loyal to the Cardinals, the team that gave him a chance.

“We told him the Cardinals would have matched the offer, and he said, ‘Really? Damn,’” said Joe Nedney, a kicker with the San Francisco 49ers who played with Tillman for Arizona in the late ’90s.

Nedney, who grew up in south San Jose, recalls Tillman had “long flowing hair and wore flip–flops and T-shirts and tattered shorts.” Rather than go out and buy a $50,000 truck with his signing money, Nedney said, Tillman rode a Schwinn Beach Cruiser bicycle to the practice field.

“He was the epitome of the California boy. But inside he was an extremely well-read and educated man,” Nedney said. “You could get into any conversation with him and he would hold his own. We used to joke that you have to do your homework before you spend time with Pat.”

Jared Schreiber, who befriended Tillman at ASU, said “it was impossible to sit down with Pat without getting into a great debate. Politics and religion, world events, he was so well-informed on issues, so capable of making other people interested. It was never about him or his own opinion,” said Schreiber, who serves on the board of the Pat Tillman Foundation. “It was about understanding what’s important and pursuing it with passion.”

Tillman also “thirsted for the adrenaline rush,” Nedney said. On a day off from football practice, some players and their wives were socializing when someone asked, “Where’s Pat?” Nedney said. “Right after that we saw two flip-flops and a T–shirt hit the ground—Pat’s up there on the roof.” A teammate tried to talk him down, but Pat vaulted into a long arcing leap, did a back flip and plunged into the pool.

“His wife, Marie, shrugged as if to say, ‘What you want me to do?’ He came up and gave a big ol’ ‘Whoo!’ and grabbed his beer,” Nedney said. “He was an adventure freak, always looking for something to defy gravity, logic and sanity.”

After the 9/11 attacks, Tillman began thinking about joining the military. He fulfilled his contract and completed the 2001 NFL season. In May 2002, Pat and his brother Kevin Tillman, a professional baseball player in the minor leagues, enlisted in the U.S. Army. The brothers completed Ranger Indoctrination later that year and served in Iraq in 2003 before being redeployed to Afghanistan.

Nedney wasn’t surprised when Tillman joined the military. “He was always searching for something meaningful. He talked to his wife, made a decision, and never looked back,” Nedney said. “Coach [Dave] McGinnis [Arizona's coach at the time] said, ‘You’re going to run into a media shitstorm,’ and Pat said ‘No, you are—I’m outta here.’ I thought he’d come back with bin Laden’s head in one hand and Saddam’s in the other.”

Though she’s hesitant to speak for her son, Mary Tillman said Pat opposed the war in Iraq. He joined the military to root out Al Qaeda, not to wage war on a country that had no connection to the 9/11 attacks, she said. Regarding Iraq, “Pat and Kevin felt there was no plan, no threat. It was really disturbing.”

The Day the Safety Died

On April 22, 2004, Tillman and his platoon were in southern Afghanistan, near the border with Pakistan, looking for Taliban insurgents. According to the Department of Defense Inspector General’s report, after a humvee had a mechanical problem, the soldiers split into two groups, Serial One and Serial Two. Pat Tillman was in the first group, which moved ahead of Serial Two. Kevin Tillman remained at the rear of Serial Two.

After Serial Two was fired upon by suspected insurgents, Serial One moved up the canyon to target the shooters. An Afghani soldier with Serial One began shooting over the canyon. Believing the Afghani was an insurgent, Serial Two soldiers began firing and killed him. Other Serial Two soldiers began shooting in the same direction, driving closer and continuing to fire after soldiers signaled they were “friendlies.”

That’s when Tillman detonated the smoke grenade, hoping his fellow soldiers would recognize him and his men. When the shooting stopped, Tillman probably believed they were identified, but a moment later another burst of fire shattered the Afghani evening.

“I noticed blood pooling up around me. I had thought that I was shot,” said Ranger Bryan O’Neal, who served alongside Tillman and may be alive today thanks to Tillman’s efforts. “I was on the ground, and so I started communicating with Pat, not realizing he had passed away, asking him if he was OK. And I had no response. There was a lot of blood everywhere, and I was starting to get really worried,” he told the House Oversight panel.

“When I could finally get my body to move, I stood up and turned around and looked at Pat, and he was slumped back on the ground, covered in blood,” O’Neal said. “And I went up to his position. I grabbed him and realized … that he had been shot in the head, and there wasn’t much left of him.”

At the age of 27, Patrick Daniel Tillman Jr., who had seemed as invincible on the battlefield as he’d been on the football field, was killed by American bullets. But that’s not what military commanders told the Tillman family.

‘Outright Lies’

Within hours of Tillman’s shooting, Army officers ordered the burning of his blood-soaked uniform and the destruction of his bullet-riddled body armor. Army spokesman Paul Boyce said soldiers had already determined that friendly fire caused Tillman’s death and burned his clothes and armor because they viewed these items as a biohazard.

Destruction of evidence in a case of friendly fire is a violation of U.S. military regulations. Soldiers also burned his journal, the IG’s report stated. “I’m angry they did that,” said Mary Tillman. The soldier who destroyed Tillman’s clothing, body armor and possessions said he was ordered to do so “to prevent security violations, leaks and rumors.”

When the soldier commented that the bullets that shredded Tillman’s body armor appeared to be American, he was told to “keep quiet and let the investigators do their jobs.” According to the Army Inspector General’s report, commanders cut off telephone and Internet communications at a base in Afghanistan and posted guards on a wounded member from Tillman’s Ranger unit. The Tillmans believe this was done to keep the wounded soldier from speaking with reporters and revealing what happened.

Though it’s Army protocol to notify the family as soon as friendly fire (also known as “fratricide”) is suspected, O’Neal (the soldier who was injured in the shooting that killed Tillman) testified before the House Oversight Committee that he was ordered by battalion commander Lt. Col. Jeffrey Bailey not to tell Kevin Tillman that fratricide appeared to be the cause of his brother’s death.

“Although some within the chain of command were aware of the suspicion that Cpl. Tillman died as a result of friendly fire, they did not publicly reveal this information because they wanted to ensure a thorough investigative process,” said Army spokesman Boyce. Several changes have been implemented to ensure more timely notification in suspected friendly fire cases, Boyce said.

Citing the Inspector General’s report, Rep. Waxman said that within 72 hours “at least nine military officials knew or were informed that Pat Tillman’s death was a fratricide, including at least three generals.” The IG’s report states that the “chain of command made critical errors in reporting Cpl. Tillman’s death.” But the Inspector General did not find a single instance of criminal negligence.

Waxman asked O’Neal, whose statement about the fratricide was changed in the documentation for Tillman’s posthumous Silver Star award, if it “troubles” him that “the Tillman family was kept in the dark” about Pat’s death for more than a month.

“Yes, sir, it does,” O’Neal said. “I wanted right off the bat to let the family know what had happened, especially Kevin, because I worked with him in the platoon. I knew that he and the family all needed to know what had happened. And I was quite appalled that when I was able to speak with Kevin, I was ordered not to tell him what happened, sir.”

“You were ordered not to tell him?” Waxman asked.

“Roger that, sir,” O’Neal replied, stating the order came from Bailey. “He basically just said, ‘Do not let Kevin know. He’s probably in a bad place knowing his brother’s dead.’ And he made it known,” O’Neal testified, “that I would get in trouble, sir, if I spoke with Kevin on it being fratricide.”

Ranger Spc. Russell Baer, who had seen Rangers shooting at Pat Tillman’s position, accompanied his friend Kevin Tillman from Afghanistan to the United States after Pat was killed. Baer was ordered not to tell Kevin Tillman that friendly fire was the probable cause of Pat’s death, according to the Associated Press. Baer followed orders and did not tell Kevin he’d seen Rangers firing toward Pat Tillman, but Baer later went AWOL. Testifying in one of the probes into Tillman’s death, Baer said, “I lost respect for the people in charge.”

Speaking at Tillman’s nationally televised memorial service on May 3, 2004, Navy SEAL Stephen White, who befriended Tillman in Iraq, spoke of Tillman’s bravery and heroism as he “took the fight to the enemy uphill to seize the tactical high ground,” repeating what Army commanders had told him: “Pat sacrificed himself so others could live.”

When White found out weeks later that the story he’d told the nation had been a lie, he felt “let down by my military,” he said at the Oversight hearing. “I’m the guy that told America how he died, and it was incorrect,” White said. “That does not sit well with me.”

Tillman’s father, Patrick Tillman, believes senior Army officers told “outright lies” about his son’s death. In 2005 he told the Washington Post: “All the people in positions of authority went out of their way to script this. They purposely interfered with the investigation, they covered it up. I think they thought they could control it, and they realized that their recruiting efforts were going to go to hell in a handbasket if the truth about his death got out,” the elder Tillman said.

“They blew up their poster boy.”

Incompetence Without Accountability

More than three years after Pat Tillman died, his family still has questions. They want to know why battlefield rules of engagement weren’t followed (rules that could have prevented Pat’s killing), why military and government leaders lied to them, who gave the orders to create the fictional account of Pat’s heroism, and why no one has been held accountable.

“Pat’s death is just a microcosm of what’s happening in this country: the lies, the spinning,” Mary Tillman said in a phone interview. “This exemplifies the way the [Bush] Administration handles everything. They’re incompetent, yet no one is held accountable. The documents were falsified—but who are these people? What are you going to do about it?”

Citing connections to the failed federal response to Hurricane Katrina and the debacle at the military’s Walter Reed hospital, Mary Tillman said, “There’s a lack of empathy on the part of the administration. It’s all lip service. There is no genuine appreciation for the suffering that’s taken place.” Rep. Waxman, chair of the House Oversight Committee, is continuing the probe into Tillman’s case and has sent letters to Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and to the White House counsel requesting communications about Tillman’s death.

Mary Tillman, a registered Republican, said “the personalities in office now are dangerous.” She believes former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, a “micromanager,” had to know before Pat’s memorial that her son was killed by friendly fire. Rumsfeld had written a letter to her son, she said, and was well aware of Tillman’s celebrity.

“He [Pat] was probably the most high-profile individual in the military at the time,” she said. “The fact that he would be killed by friendly fire and no one would tell Rumsfeld is ludicrous.”

Mary Tillman believes President Bush knew as well.

On April 28, 2004, six days after Pat died, White House speech writer John Currin sent the Pentagon an email asking for information about Tillman’s death for a speech Bush would deliver at the upcoming correspondents’ dinner. The next day, according to testimony at the Oversight Committee hearing, a P4 (high-priority) memo was sent to three top generals, including Gen. John Abizaid, then head of Central Command, stating it was “highly possible that Corporal Tillman was killed by friendly fire.”

Rep. Elijah Cummings (D–Maryland) said this memo “seems to be responding to inquiries from the White House—and here’s what it says, ‘POTUS, meaning President of the United States, and the Secretary of the Army might include comments about Corporal Tillman’s heroism [without mentioning] the specifics surrounding his death.’” The message, whose author wasn’t disclosed, expresses concern that the president and Rumsfeld could suffer “public embarrassment if the circumstances of Corporal Tillman’s death become public.”

When the president spoke at the correspondents’ dinner the following Saturday, “he was careful in his wording,” Rep. Cummings said at the Oversight hearing. “He praised Pat Tillman’s courage, but carefully avoided describing how he was killed. It seems possible that the P4 memo was a direct response to the White House’s inquiry. And if that is true, it means that the White House knew the true facts about Corporal Tillman’s death before the memorial service and weeks before the Tillman family was told.”

Though Mary Tillman has been frustrated by the Bush Administration’s resistance to her inquiries, the family has had some contact from the President. During a halftime ceremony in September 2004 to retire Pat Tillman’s jersey at an Arizona Cardinals game, a video of the president was shown.

“They (the Cardinals’ management) didn’t ask us if it was ok to broadcast the video,” Mary Tillman said, adding that thousands in the Arizona crowd booed Bush. “I was angry. It was just [the Bush Administration's] way of using Pat one more time—it changed the tone of everything.”

The Family From Hell

Perhaps the most revealing statements about the heartlessness of Tillman’s military superiors came from Lt. Col. Ralph Kauzlarich, who directed the first official inquiry into Tillman’s death. Kauzlarich said the Army did ballistics work and may know who shot Pat Tillman. “I think they know [who fired the shots that killed Tillman],” Kauzlarich said in an interview with ESPN. “But I never found out.”

With even greater callousness, Kauzlarich said of the Tillman family: “These people have a hard time letting it go. It may be because of their religious beliefs.” Noting that Kevin Tillman declined to have a chaplain say prayers over Pat’s body, Kauzlarich said: “When you die, there is supposedly a better life, right? Well, if you are an atheist and you don’t believe in anything, if you die, what is there to go to? Nothing. You are worm dirt.” Mary Tillman says she’d like nothing better than to let go. “I’d like for this to come to a conclusion so we can focus on the more positive aspects of Pat’s life,” she said. But she’s not going to move on until she gets the truth.

Norman Solomon, author of War Made Easy, applauds the Tillmans for their courage and perseverance in trying to uncover what happened to Pat.

“They’re tough, smart and not intimidated,” he said. From the Pentagon’s perspective, “the Tillmans have become the family from hell.” But overcoming a widely distributed and oft-repeated lie isn’t easy, Solomon said, because “first impressions are imprinted on people.”

As Mark Twain said more than a century ago: “A lie can get halfway around the world before the truth even gets its boots on.”

Pat’s Run

As the sun breaks through a layer of misty clouds on the last Sunday morning in April, thousands of runners gather on Via Valiente outside Leland High School for Pat’s Run, a fundraiser for the Pat Tillman Foundation, which supports youth engaging in projects for social change. The run draws soldiers, football players, war opponents and cheerleaders. There’s not a trace of political activism, just 5,000 amateur athletes united in their desire to honor Tillman’s memory and support the foundation.

At Leland’s field, renamed “Pat Tillman Stadium,” 15–foot–high burgundy balloon clusters spell out “Pat’s Run.” A quote from Emerson is posted at the finish line: “Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.” Some runners race to the finish, other push strollers or jog with their dogs over the 4.2-mile course (42 was Tillman’s football jersey number in high school and college).

After running the race, USMC Lt. Steve Cooney of Santa Rosa called Tillman “a strong American who died an honorable death fighting for his country.” Another soldier, Army reservist Michael B. of Santa Clara, who declined to give his last name, said he understood how friendly fire deaths can happen, “but if it were my family, I’d want them to know the truth.”

Melanie Corpus, a young woman from San Jose, had the Pat’s Run logo inked onto her cheek. She became tearful when speaking about Tillman, showing that Tillman touched people who didn’t know him personally. “He gave up everything,” she said. “He was just a beautiful person.”

Many who attended the run didn’t know the Tillman family has been deceived about Pat’s death. But some had read about the official mendacity: Jennifer Green of San Jose said she “liked Tillman even better” once she learned the truth about him. “He was a thinker, he read [Noam] Chomsky, he joined [the Army] for all the right reasons.”

Arizona State University student Mackenzie Hopman has enrolled as a Pat Tillman Scholar in ASU’s Leadership Through Action, an accredited one–year program created after Tillman’s death to encourage students to engage in community projects. She traveled from Tempe to be part of the run in San Jose.

Hopman became a Tillman Scholar because she was inspired by Tillman. “As Pat was walking down the long corridor of life, he had goals in mind: ASU, pro football, the military,” Hopman said. “There were doors on either side of this corridor, and instead of breezing past each door, he’d stop and peek inside and then run a few yards and leave it behind. He never lost sight of what was ahead of him and where he wanted to be. He was always there 150 percent, every day, every practice, every moment.”

Tillman “was honest and forthright and open from the get go,” she said. “I imagine that if he were to see his own situation he’d say, ‘Just be honest and let them know what happened.’” Tillman “didn’t need a [false] story about his heroic death,” Hopman added. “He lived a heroic life.”

After the adults run their course, hundreds of kids line up on the track surrounding Leland’s football field for a short (0.42–mile) run of their own. Charging across the starting line with the exuberance and enthusiasm that Pat maintained throughout his life, the kids race toward the finish.

Alex Garwood, Pat’s brother–in–law and executive director of the Tillman Foundation, ascends a podium to hand out trophies as U2′s “It’s a Beautiful Day” sweeps across the field.

“What a positive day,” Garwood says in an interview after the ceremony. “But we should not have to be doing this. Pat should be here.”

–

Michael Shapiro’s stories, which range from investigative reporting to travel topics, have appeared in the Washington Post, National Geographic Traveler and The Sun. He is the author of ‘A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives, and Inspiration.’ For more about Shapiro and his work, see www.michaelshapiro.net.

For more information: Pat Tillman Foundation, to learn more or donate: www.pattillmanfoundation.org. Department of Defense Inspector General Review of Matters Related to the Death of Cpl. Patrick Tillman: www.defenselink.mil/home/pdf/Tillman_.... Video of House Oversight Committee hearing “Misleading Information from the Battlefield”: http://oversight.house.gov/story.asp?...

Was Pat Tillman murdered? SF Chron.

Ballistics evidence suggests the bullets that killed NFL-player-turned-soldier Pat Tillman were fired from just 10 yards away. We know it was friendly fire — his mother believes it may not have been an accident. Here’s a review I wrote for the SF Chronicle of the book written by Tillman’s mother. To read it, click this link, or see the text below:

“Boots on the Ground by Dusk” by Mary Tillman with Narda Zacchino

Review by Michael Shapiro, June 15, 2008

You’ve most likely heard of Pat Tillman, the former NFL standout from San Jose who gave up his football career to enlist in the U.S. Army. And you probably know that in 2004, weeks after the Army told his family and the nation that Tillman died heroically in a firefight with the enemy in Afghanistan, the military acknowledged Tillman was killed by bullets fired by his fellow Army Rangers.

But what you may not know is that Pat’s mother, Mary Tillman, author of “Boots on the Ground by Dusk,” believes his April 22, 2004, death in a narrow Afghan canyon may not have been an accident. She thinks it could have been premeditated murder. And she has some evidence to back this up.

Mary Tillman has tenaciously and persistently investigated her son’s death since irregularities in the Army’s narrative began to surface almost immediately after her son died. One example: She learned the Army burned her son’s bullet-riddled body armor, a violation of policy, in what she believes was an attempt to cover up his death by “friendly fire,” an appallingly euphemistic term she deplores.

So it was with great anticipation one dives into “Boots,” eager to learn what Mary Tillman believes happened to her son. Written with former Chronicle Deputy Editor Narda Zacchino, the book opens with a heartrending scene of Mary sitting by a fire pit in her front yard, smoking and blowing out her “anger, frustration and sense of crippling loss.” Then she flashes back to childhood vignettes about Pat and his two brothers, Kevin and Richard. We see Pat climbing trees, questioning authority, and excelling at soccer, which give some clues to the man he’d become. But at times this seems a bit like a family slide show that goes on too long.

“Boots” jumps to May 2004 when Mary learns – from a reporter rather than from the military – that her son was killed by friendly fire. Her description of the tears spilling down her cheeks can bring tears to the reader’s eyes. We don’t just see this mother’s pain – we feel it. The next flashback chronicles Pat and Kevin’s post-9/11 decision to the enlist in the Army. Though the Tillman family has a long tradition of military service, Mary and her brother Mike fear “Bush’s cockiness and lack of empathy.” Mike says he’s proud of Pat and Kevin’s willingness to defend their country, but “I don’t want them fighting for this commander-in-chief.”

The shocker comes on Page 60, when, after a series of inconsistent briefings with senior military officials, Pat’s distraught brother Richard says, “I think my brother was f- murdered.”

Much of the rest of “Boots” segues from accounts of the family’s ordeal of trying to uncover information about Pat’s death to stories of Pat’s brashness.

“Boots” shows Pat graduating summa cum laude with a 3.86 GPA from Arizona State. He was a voracious reader whose appetite ranged from Thoreau to the Economist, from the Book of Mormon and the Koran (though he wasn’t religious), to Noam Chomsky and Bob Woodward’s “Bush at War.”

The undersized (5-foot-11) NFL player was so grateful to the Arizona Cardinals, which drafted him, that after becoming a successful safety he chose to stay with the team and turned down a much more lucrative $9.6 million contract from St. Louis. After fulfilling his contract with Arizona, he joined the Army.

Though he did not support the Iraq war and enlisted to serve in Afghanistan, Tillman was initially assigned to duty in Iraq. In “Boots,” Kevin, who served alongside him, recalls a time when Pat saw a frightened old man with “a look of terror” in his eyes. Pat shouts – in Arabic – “We will not harm you,” a testament to his compassion and ability to speak the local language.

Admirably, Mary Tillman doesn’t deify her son – her portrait is realistic and shows some of his faults, such as Pat’s impatience and involvement in a high school fight.

But “Boots,” called a “Tribute” in the subtitle, shows Tillman as the best of what a young American man can be: hard-working, honest, constantly striving to improve and willing to sacrifice everything in service to his country. Which makes the deceit surrounding his death that much more outrageous.

But was he murdered? Mary Tillman notes that spring 2004 was a disastrous time for the Bush administration with the failure in Fallujah and the Abu Ghraib torture scandal. “I wonder if it’s possible the ambush was staged,” she writes. “I wonder if Pat was killed (for PR reasons) on purpose.”

A July 26, 2007, Associated Press report revealed medical evidence stating it appeared Tillman was shot by an M-16 from much closer than originally reported: “a mere 10 yards or so away.” This could lend credence to the family’s belief his death wasn’t accidental.

Confoundingly, this evidence isn’t mentioned in “Boots,” which ends in September 2007, weeks after this report surfaced. Despite Mary Tillman’s best efforts, we may never know exactly how or why Patrick Daniel Tillman was killed. But the book’s conclusion would have been much more satisfying if this insightful woman shared what she now believes. {sbox}

Michael Shapiro is the author of “A Sense of Place” and wrote an investigative feature about Pat Tillman last year for a South Bay weekly newspaper. E-mail him at books@sfchronicle.com.

This article appeared on page M – 1 of the San Francisco Chronicle

Read more: http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/06/13/RVJ910U74N.DTL#ixzz1o8ACGP6h

February 29, 2012

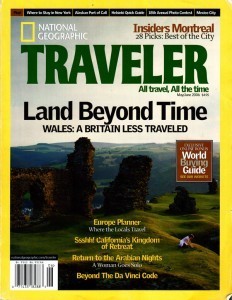

Somewhere Beyond Time: My cover story on Wales in Nat’l Geo Traveler

Jan Morris has been my mentor and a muse. When National Geographic Traveler asked me to travel to Wales to interview her and write about her corner of her beloved homeland, I leapt at the chance. I planned to meet Jan on my first day in Wales and have her set my itinerary, but she had other ideas.

The final version that appeared in NGT was trimmed slightly. One section that got cut was about a homey museum devoted to the Welshman David Lloyd George who steered Britain through one of its most difficult periods. Here’s the story:

By Michael Shapiro

“Come, I’d like to show you something,” says Jan Morris, the eminent Welsh author. We’re at the rustic Pen-y-Gwryd, a 200-year-old lodge clinging to the foothills of Mount Snowdon, Wales’ highest peak, where climbers Edmund Hillary, John Hunt, and others trained for 1953 Everest expedition. After a hearty lunch of steak pie and Guinness stout in the lodge’s Smoke Room, we walk under low ceilings past mullioned windows. The scent of wood smoke mingles with the aroma of fermented ales.

Look up, Morris says. Inscribed on the ceiling above us in thick black ink are the bold signatures of the climbers: E.P. Hillary, John Hunt, Charles Evans, and James Morris, then a reporter for the Times of London and the sole journalist on the 1953 Everest expedition. (Back then, Jan was called James, but we’ll get to that story later.) The climbers had returned to the lodge for reunions in the years after the famed 1953 expedition, the first to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain, and had left their marks on the lodge’s ceiling. Asked how high she’d climbed, Morris laughs and says, “It gets higher every year.” Thanks to Morris, who hustled down Everest the day the summit was reached and relayed an encoded message to the Times, news of this grand achievement reached Britain on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Look up, Morris says. Inscribed on the ceiling above us in thick black ink are the bold signatures of the climbers: E.P. Hillary, John Hunt, Charles Evans, and James Morris, then a reporter for the Times of London and the sole journalist on the 1953 Everest expedition. (Back then, Jan was called James, but we’ll get to that story later.) The climbers had returned to the lodge for reunions in the years after the famed 1953 expedition, the first to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain, and had left their marks on the lodge’s ceiling. Asked how high she’d climbed, Morris laughs and says, “It gets higher every year.” Thanks to Morris, who hustled down Everest the day the summit was reached and relayed an encoded message to the Times, news of this grand achievement reached Britain on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

I’d come to northwest Wales, to the region of Gwynedd, where Welsh is still widely spoken and where Welsh culture remains strong, to see Wales through Morris’s eyes. I hoped to trace Morris’s footsteps up Yr Wyddfa (the Welsh name for Mt. Snowdon, it means “grave of the giant”), to explore the imposing castles that ring the rugged Welsh coast, to see the great harbor town of Porthmadog and ride a 19th-century steam train to the slate quarries of Blaenau Ffestiniog, and to visit the whimsical Italianate village of Portmeirion, designed by Morris’s late friend, the architect Clough Williams-Ellis.

Most of all, I hoped that Morris could point me toward an understanding of how the tiny nation of Wales has survived – even thrived – with its language and culture intact, despite seven centuries of domination by England, its larger and more powerful neighbor to east. About the size of Massachusetts, Wales is a land of just 3 million people, surrounded by almost 60 million English, Irish, and Scots. Only about 200 miles long and as little as 40 miles wide, one can drive the length of Wales in less than a day and across it in a couple of hours.

* * *

Entering Wales by locomotive, I marvel at the mortarless stone walls and watch recently born lambs skip briskly across spring-green fields. Sheep, which have provided the Welsh with meat and wool for centuries, seem to cover almost every hillside and outnumber people in Wales by more than three to one. As the train heads up the west coast of Wales, tidy whitewashed houses dot the hills to the east and broad views of Cardigan Bay open to the West.

Embodying the warm hospitality of Wales, Morris has kindly invited me to visit her home in Llanystumdwy (the name means a holy place at a bend in the river) before our lunch at Pen-y-Gwryd. After rolling down the rutted driveway, Morris cuts the engine and I can hear the River Dwyfor sing sweetly nearby. Atop the thick-walled stone house is a creaky weathervane, a symbol of Jan’s dual Welsh and English ancestry: E and W mark east and west, G and D stand for Gogledd and De, the Welsh words for north and south.

Embodying the warm hospitality of Wales, Morris has kindly invited me to visit her home in Llanystumdwy (the name means a holy place at a bend in the river) before our lunch at Pen-y-Gwryd. After rolling down the rutted driveway, Morris cuts the engine and I can hear the River Dwyfor sing sweetly nearby. Atop the thick-walled stone house is a creaky weathervane, a symbol of Jan’s dual Welsh and English ancestry: E and W mark east and west, G and D stand for Gogledd and De, the Welsh words for north and south.

Morris, who turns 80 this year, has spent much of her life traveling, writing incisive books about Venice, Oxford, Sydney, Hong Kong, and Trieste, among other places. For the past several decades, she has always returned to this humble plot in remote northwestern Wales. In the early 1970s, Morris underwent a sex change operation and has since lived as a woman. She has remained with her partner Elizabeth, the mother of their four children, for more than 50 years.

We enter their home through an old stable door, which opens in upper and lower halves, and walk into a kitchen floored with Welsh slate. The next room is a long library with neatly organized bookshelves reaching from floor to ceiling. Upstairs over tea with Elizabeth, Jan, and their Norwegian forest cat, Ibsen, Morris and I get to talking.

“For me the essence of Wales is conflict,” she says. “It’s a constant struggle to keep Welsh culture alive” as more and more English families settle in Wales, bringing their habits with them. On the bright side, all Welsh schoolchildren today learn their mother tongue so knowledge of the Welsh language, one of Europe’s oldest, is on the rise. And though Wales remains part of the United Kingdom and is mostly governed from London, it recently formed its own national assembly.

“We have a nation-state,” Morris says. “I love the nation (of Wales) – it’s the state part of it I hate. I’m fed up with patriotism and nationality, but somehow we’ve got to preserve the culture,” she adds, noting that the Welsh word for Wales, Cymru, means comradeship. “I like the nature of Welsh civilization which is basically very kind, not ambitious or thrusting. It’s based upon things like poetry and music, which are still deeply rooted in this culture.” < note: Ok to cut these last 2 sentences are from A Sense of Place – or we could say these quotes came from ASOP.>

Before leaving I ask Morris about places to see and people to meet. She deftly sidesteps the question, but as we part she says, “Oh, you may want to look in on the Archdruid.” And then she bids me farewell with a wave and smile.

I find the Archdruid, Dr. Robyn Lewis, near the tiny town of Nefyn on the north coast of Wales’ Llyn peninsula. Lewis is the Archdruid of the National Eisteddfod, an annual cultural celebration dating to the 12th century that honors Wales’ top poets and prose authors. The weeklong festival, the most important cultural event in Wales, is filled with public performances of poetry and music, the arts that enliven the sometimes bleak Welsh days.

Somehow I imagine the Archdruid living in a low-slung cob hut surrounded by a circle of stones, but Lewis, who has lived in Nefyn since he was 3, resides in a contemporary home with sweeping views of the Llyn peninsula’s northern coastline. A stained-glass red dragon, the proud symbol of Wales, hangs in his front window, and hundreds of Welsh books line the walls. “I buy the Welsh books” to support local authors, Lewis says. “The English ones I get from the library.”

A distinguished author and retired judge, Lewis presided from 2002 to 2005 over the Gorsedd of Bards, a body composed of Wales’ literary lights responsible for the colorful Eisteddfod ceremony. Tall and lean but agile despite his advanced age, the bespectacled Lewis shows me an antique wooden chair almost as high as his ceiling, awarded to an Eisteddfod poetry winner in 1890. Lewis won the Eisteddfod award for prose in 1980, making him eligible to become an Archdruid. Three major awards are bestowed during the weeklong event: the literary medal is presented to the author of the best prose work; the crown goes to the composer of the best volume of poetry; and the great chair is awarded to the author of the best strict meter poem, a complex and distinctly Welsh type of poetry.

Rather than describe the Eisteddfod, Lewis plays a video of the 2003 ceremony, when Jan’s son Twm Morris (Twm, pronounced “Toom,” is Welsh for Tom) won the award for strict meter poetry. The silver-haired Archdruid, clad in a cream-colored robe with a golden breast plate and a sash emblazoned with red dragons, clasps a golden scepter and opens the proceedings. The bards file in wearing blue, green, or white robes and fill the stage. Two trumpeters sound a fanfare and the lights go down. Though Twm, seated in the audience, knows of his selection, the audience remains in the dark until a spotlight shines brilliantly on the winner. Twm stands, beaming, to receive his comrades’ wild cheers.

While Twm remains standing, the mistress of robes and four attendants in white nun-like attire proceed up the aisle to offer Twm his Eisteddfod robe. Unbeknownst to Twm, Lewis had arranged for Jan to serve as one of the attendants, and as she walks up the aisle Jan’s smile shines almost as brightly as the spotlight illuminating her son.

“Is there peace?” the Archdruid booms, adhering to tradition. “There is peace,” the audience responds. The Archdruid declares: “I now proclaim that Twm Morris has been chaired chief poet.” Twm takes his outsize chair as a young woman presents him with a horn of plenty and offers him the wine of welcome. A maiden offers a basket of flowers followed by a group of young girls dance. A massive sword, carried by a former rugby player (they’re the only ones strong enough to carry the sword, Lewis tells me) remains in its sheath, a symbol of peace. The ceremony closes with the national anthem. “That’s the Welsh anthem, ‘Land of our Fathers,’ not ‘God Save the Queen,’ ” Lewis says dryly as he switches off the video.

Like most Welsh citizens, Lewis is proud of his heritage. “You have one nation with 50 states – we have one state (the United Kingdom) with four nations (England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales),” Lewis says. And, though most of Wales’ castles were built by English invaders, Lewis is proud of the citadels that fortify the Welsh coast: “We’re very rich in castles – that meant it was quite a job to keep us down.”

Though Morris is only half Welsh by birth, Lewis is unrestrained in praising her contributions to Wales. “She expresses her Welshness through English and that gets to the English establishment. If I express it, no one takes much notice,” he says. “I wouldn’t hesitate to call her a genius.”

I hop into my rented VW Passat, a big car by Welsh standards, and drive a few miles up the coast. From the narrow main road, I turn down a skinny lane that plunges almost vertically towards the shoreline. At the base of the hill is Nant Gwrtheyrn, the Welsh language institute and heritage center. Once a thriving quarry town, Nant Gwrtheyrn was abandoned in the 1950s. In the early ’70s squatters turned the low-slung L-shaped complex of stone buildings into a commune. It’s not hard to see why: with lush green fields and awe-inspiring views of the frothing surf, Nant Gwrtheyrn’s aesthetic glories complement its splendid isolation.

Philip Jenkins, a 35-year-old rock musician from the Welsh capital Cardiff, told me he’d been hoping to enroll at Nant Gwrtheyrn for years but had to save money. After receiving a scholarship for half the tuition, he came to the institute. Speaking Welsh isn’t a necessity, but Jenkins wanted to learn his mother tongue. “I like the sound; I like the rhythm,” he said. “It was in my family a century ago. We’re pushing back against homogenization. People are looking to their roots.”

These roots go back to Wales’ remote Celtic past. Welsh “has changed in essence so little down the centuries,” Morris writes in The Matter of Wales, “that an educated Welshman can still read, without too much difficulty, the Welsh of the Middle Ages.” Noting the language’s importance, Morris writes: “Without it, it can be said, there would be no Wales by now, only another province of England.” And in A Writer’s House in Wales, she says: “The very existence of Welsh, still defiant after so many centuries of alien pressure, is a magic in itself, and those with ears to hear find in its very cadences … a beauty akin to the music of the spheres.”

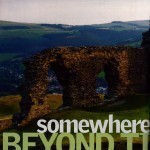

A few miles up the coast is Caernafon, the ancient walled city best known for its 13th-century castle. Built by King Edward I to quash ongoing Welsh rebellions against English occupation, the citadel juts like an iron fist into the Menai Strait. Composed of octagonal towers and serrated walls, the stronghold at Caernafon is a symbol of English dominion over Wales. Stone eagles, emblems of power, perch upon the castle’s battlements.

That evening I walk across the Afon Strait on the Aber bridge which rotates to let boats in and out of the harbor. A pair of white swans paddles through the inlet followed by five fluffy two-day-old chicks. “They were still in the egg Friday,” says Glyn Jones, a middle-aged man standing nearby. Gazing out at the lagoon, Jones extols the virtues of living in the Caernafon area: the easy pace, coastal fishing, neighborly warmth. But he laments that most young adults are heading to the capital, Cardiff, for work. English retirees and vacation-home buyers have driven up house prices in Wales, Jones says wistfully. “My friend’s daughter is a teacher and her husband is on the county council, but they can’t afford a mortgage.”

As darkness descends upon Caernafon, orange floodlights bathe the castle in a warm hue, softening its menacing facade. A swan flies so close I can hear the whoosh of its wings as seagulls squawk above. Two young men in Wellies climb into a rowboat — one doffs his cap as they motor under the bridge. The tide rises quickly, lifting a floating restaurant out of the tidal mud and providing a luminous reflecting pool for the castle. The ripples turn the castle’s reflection into a shimmering impressionist painting.

I drive on to Porthmadog, an old port town just seven miles from Morris’s home that serves as a convenient base for exploring her region of Wales. In the harbor, where a century ago tall-masted, slate-hauling ships were loaded round the clock, a few dozen pleasure craft bob up and down. I throw a windbreaker over my shoulders and walk along the Cob, an embankment crossing an estuary of the Glaslyn River. With views Mount Snowdon and its foothills, “This grand prospect is like an ideal landscape,” Morris writes in The Matter of Wales, “its central feature exquisitely framed, its balance exact, its horizontals and perpendiculars in splendid counterpoint. … It is the classic illumination of Wales.”

Morris’s book describes the remarkable skill of Welsh miners and quarrymen and the brutal hardships they faced. To see where they worked, I ride the Ffestiniog narrow-gauge rail that winds thirteen miles from Porthmadog to the slate quarries at Blaenau Ffestiniog. The four-car train is pulled along the two-foot-wide tracks by a 19th-century steam engine. Built in the 1830s to haul slate from the mountains to the coast, the Ffestiniog Railway is one Britain’s oldest railways.

During the trip’s first few miles we pass so close to people’s houses that I can see the photos on their nightstands. Next we ascend into woodlands graced with turquoise lakes. After the 75-minute ride to Blaenau Ffestiniog, we have just a few minutes to explore the old slate quarries – you can still see mountains of waste slate and the trails the men slid down at the end of their shifts.

The train’s driver, Paul Davies, rotates the engine for the return journey and invites me to ride up front with him. He tells me how the quarrymen would gather in “cabans,” typically small slate buildings, to play classical music, read poetry, and sing in choirs. “They may not have been formerly educated,” Davies says, “but the Welsh choirs were the stuff of legend.”

Back in Porthmadog, a television drama for Channel Four Wales is being filmed outside Y Llong (The Ship), a pub next to the hotel where I’m staying. The dialogue is in Welsh except for an expletive in English. “We don’t have any swear words – make love not war,” says Pat Hughes, the pub’s manager, as we watch the crew reshoot the scene. Pat tells me his countrymen had to protest to get a TV station that aired programs in Welsh. A Welshman named Gwynfor Evans went on a hunger strike in 1981 demanding the British government honor its promise to offer a Welsh-language TV channel, and Margaret Thatcher’s government caved. “The way we look at it, we’ve never been conquered,” Hughes says. “We’ve still got our language.”

A few miles down the road is the chimerical village of Portmeirion, designed by Welsh architect Clough Williams-Ellis, an old friend of Morris. Crowned by a belltower, the village, constructed from the 1920s through the 1970s to attract tourists, overlooks the estuary of the Dwyryd River. With buildings painted bright yellow, aquamarine, and terra cotta, Portmeirion is an uplifting contrast to the mostly colorless stone buildings of northern Wales. Morris calls it “a floating fantasy above the sea.” Portmeirion was the setting for the British cult drama “The Prisoner.” Soon after the short-lived series began airing in 1967, the number of visitors to Portmeirion jumped tenfold.

“It’s sort of a light opera approach to architecture,” says Robin Llywelyn, Clough’s grandson who serves as Portmeirion’s managing director. Llywelyn tells me his grandfather believed – like his half-Welsh colleague Frank Lloyd Wright – that architecture need not dominate the landscape; it could enhance it. “He never had a master plan,” Llywelyn says, which is clear from Portmeirion’s hodgepodge of styles and colors. But somehow this Willy Wonka-esque concoction of shops, villas, and cafés works, delighting young and old. Williams-Ellis was “always pleased to see kids enjoy it,” Llywelyn says. “Adults would want to know what it means. He’d say, ‘If I could have explained it in words, I wouldn’t have had to build it.’ ”

Beyond the village is a shady forest with trees imported from around the world and ponds dappled with lily pads. The fern-shrouded paths are brightened by magenta foxgloves. Coming around a bend, I stumble upon a dog cemetery; its heartfelt tributes – some in English, others in Welsh – are deeply moving. Says one little tombstone, “He gave us love, he gave us joy, he truly was, his father’s boy.”

Morris had mentioned that David Lloyd George, the Welshman who served as British Prime Minister from 1916 to 1922, grew up in her town, Llanystumdwy, so I returned there to visit the Lloyd George Museum. Located in the center of town, the museum honors this quintessentially Welsh leader: before he became prime minister Lloyd George fought for a “people’s budget” to ease the tax burden on the working class. In 1911 he proposed the National Insurance Act, laying the foundation for the social security reforms that transformed Britain during the 20th century. Taking power during the Great War, Lloyd George was hailed for leading Britain to victory, but his career deteriorated into acrimony over the partition of Ireland.

Part of the museum is the house where Lloyd George grew up with his uncle, a shoemaker. On a table are some old shoemaking tools – a photo of Abraham Lincoln hangs on one of the home’s thick stone walls. Iolo Wyn Edwards of the museum staff tells me that Lloyd George’s uncle admired Lincoln and imparted the American’s values to young Lloyd George, whose father had died when Lloyd George was just a year old. Just behind the museum, in the woods by the River Dwyfor, is Lloyd George’s grave. I enjoy a peaceful walk alongside the gently flowing river, the same stream that meanders by Morris’s home, until two military jets noisily slice the sky.

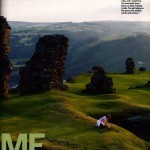

The last day of my trip, I awake to blue skies, a rarity in typically tenebrous Wales. I lace up my hiking boots and prepare to climb Mount Snowdon, Wales’ highest peak at 1085 meters. A mere foothill compared to the world’s great mountains, Snowdon offers a moderately challenging climb over rocky trails. I ascend the popular Pen-y-Gwryd track, a wide gravelly trail which begins steeply and then reaches a plateau with views of two deep blue lakes at the foot of a massif. After two hours of climbing, I approach Snowdon’s summit. At last I understand why Morris, who often writes of her “imagined” Wales, wouldn’t lay out my itinerary: She didn’t want to confine me to seeing her Wales. She wanted me to find my own.

From the empyrean summit of Snowdon I can see for miles and miles: to the west, the foothills bumping down to the Pen-y-Gwryd lodge; to the distant south, the bustling port town of Porthmadog; to the far north, the walled city of Caernafon and its citadel. The Llyn peninsula to the east is blanketed by clouds, but no matter: I can almost see the Archdruid in his Eisteddfod robes; I imagine Morris reading one of her son Twm’s poems in her library; I can envision young Lloyd George helping his uncle at his shoemaker’s workshop, hearing stories about a great egalitarian leader in a distant land called America.

Except for the first decade of the 1400s, the Welsh have lived under English rule for more than seven centuries. So many times the Welsh language and culture have seemed on the brink. With globalization and a cresting wave of English immigrants, the 21st century brings new threats to the rich heritage of Wales.

During my day with Morris I ask her if these are good times for Wales. “They’re better than they have been, but the more I think about it, the more concerned I become,” she says. “All we can do is keep smiling and keep fighting. We are always struggling.”

Morris raises the distinctly Welsh concept of hiraeth, an ineffable yearning. “We’re always longing for something,” she says, “but we’re not sure if it’s an ideal past or a better future.” Perhaps it’s this “perennial vision of a golden age, an age at once lost and still to come – a vision of another country almost, somewhere beyond time or even geography,” as Morris writes in The Matter of Wales, that gives the Welsh the strength and creativity to keep bucking the tide of history.

Michael Shapiro first met Jan Morris in 1992 at a travel writing seminar near San Francisco. “When I first met Jan she seemed like a visitor from another time,” Shapiro says. He interviewed Morris in Llanystumdwy for his book A Sense of Place: Great Travel Writers Talk About Their Craft, Lives, and Inspiration (Travelers’ Tales, 2004) which was briefly excerpted in National Geographic Traveler.

February 28, 2012

Sumptuous cuisine in Lima, Peru

Sometimes dream assignments get even dreamier. After asking “if I’d be willing” to go to Peru and take a cruise down the Amazon, my editor said something like: As long as you’ll be in Lima, try a few top restaurants and we’ll run a sidebar on Peruvian food, which is becoming globally recognized. So after spending four days on the Amazon, I spent three days in Lima restaurants and got so much good material that the sidebar became a full-fledged feature. Here’s an excerpt – :

Sometimes dream assignments get even dreamier. After asking “if I’d be willing” to go to Peru and take a cruise down the Amazon, my editor said something like: As long as you’ll be in Lima, try a few top restaurants and we’ll run a sidebar on Peruvian food, which is becoming globally recognized. So after spending four days on the Amazon, I spent three days in Lima restaurants and got so much good material that the sidebar became a full-fledged feature. Here’s an excerpt – :

The gigantic red dragon with pointy scales and sharp fangs stops me in my tracks. I spot the fiberglass monster clinging to the top of the wall at Madam Tusan, Chef Gaston Acurio’s newest Lima restaurant, in the fashionable Miraflores neighborhood. The defiant beast speaks volumes about Peruvian cuisine: proud, authentic, and announcing itself to the world.

Acurio, who created the internationally beloved seafood restaurant La Mar, is Peru’s best-known chef. Madam Tusan, perhaps his most daring restaurant, has been dishing out a fusion of Chinese delicacies and Peruvian accents since opening last May. Tusan, which means a person of Chinese descent born in Peru, is just one of many bright lights spicing up Lim a’s burgeoning culinary scene. As Peru’s chefs garner international acclaim for their culinary skills, they’re embracing fruits, vegetables, and spices from the Amazon and Andes, bringing the flavors of Peru’s jungle and coastal regions to the capital.

a’s burgeoning culinary scene. As Peru’s chefs garner international acclaim for their culinary skills, they’re embracing fruits, vegetables, and spices from the Amazon and Andes, bringing the flavors of Peru’s jungle and coastal regions to the capital.

Chefs like Acurio are newly crowned superstars at home and around the world – La Mar has spawned restaurants in San Francisco, Santiago, and Sao Paulo, and Acurio opened La Mar Cebicheria Peruana in New York in September.

Thanks to the global fame of Acurio and other Peruvian chefs, it seems like you now find a culinary academy on almost every Lima corner. Young Peruvians who used to venture off to Paris for kitchen training can now master their skills without flashing their passports. Some Europeans are even donning aprons in the city’s culinary classes, and a Lima food fair called Mistura draws hundreds of thousands of people from around the world each September to sample delicacies prepared by Peru’s top chefs.

Amazon cruising: A Ride in the Wild

I always thought if I ever floated down the Amazon it’d be in a dugout canoe on a shoestring adventure. But when the editor of a magazine for country club members asked me to join a luxe cruise, of course I went and had a fabulous time. The local guides were the highlight – and if you view the photo gallery, please note that the caiman was handled gently and returned to the riverbank unharmed. Here’s an excerpt from my story for Private Clubs magazine – for the full story, :

I always thought if I ever floated down the Amazon it’d be in a dugout canoe on a shoestring adventure. But when the editor of a magazine for country club members asked me to join a luxe cruise, of course I went and had a fabulous time. The local guides were the highlight – and if you view the photo gallery, please note that the caiman was handled gently and returned to the riverbank unharmed. Here’s an excerpt from my story for Private Clubs magazine – for the full story, :

“Vamos, cholo!” shouts our guide, Victor Coelho, to the skiff driver as we embark on an excursion down a remote stream in the Peruvian Amazon just after sunset. Soon, the skiff’s spotlight reveals a pair of gleaming crimson eyes in the undergrowth. Victor asks me to hold his legs as he goes belly down on the skiff’s bow, his arms reaching over the launch toward the riverbank.

With catlike reflexes, he pounces toward the shallows, where splashing and thrashing ensue. When Victor shouts and I pull back on his ankles, he leaps up, holding a yard-long creature above his head, its tail whipping furiously back and forth.

“Oh my God – it’s a black caiman,” he exclaims. “These are endangered – look at this!” Victor places one arm under the neck of the scaly creature, best described as a small alligator with teeth that could do some serious damage. “Want to hold it?” he asks. “Just put your hand under his neck and you’ll be fine.”

“Oh my God – it’s a black caiman,” he exclaims. “These are endangered – look at this!” Victor places one arm under the neck of the scaly creature, best described as a small alligator with teeth that could do some serious damage. “Want to hold it?” he asks. “Just put your hand under his neck and you’ll be fine.”

I recoil but then realize this could be a once-in-a-lifetime chance I shouldn’t pass up. I take the menacing-looking carnivorous reptile – following Victor’s handling instructions to a “T” – and pose for a snapshot, exultant that I didn’t let fear stop me from experiencing this transcendent moment. Victor then releases the caiman unharmed back into the wild.

February 27, 2012

Heavenly voices: How Ladysmith Black Mambazo went from dream to fame

I recently interviewed a founding member of the South African vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo who told me the band started as a dream – see excerpt below. The band plays March 2 at Napa’s Uptown Theater – here’s the excerpt:

Mambazo’s music, a hybrid of Zulu harmonies and gospel stylings, came to the group’s founder, Albert Shabalala, in a series of dreams in 1964.