Craig Lancaster's Blog, page 4

June 26, 2014

Waiting for the wait to stop*: my writing process

*—any time I get to quote a song by Joe Pernice, I’m gonna do it. Fair warning. Thanks to a nod by David Abrams, author of the fine comic war novel Fobbit and an all-around awesome fellow, I’m going to take part in a blogging exercise that has been making the rounds for a while now. I’ll chat a bit about the highly unscientific, often maniacal, regularly confounding process that leads to the writing I do. The idea here is to answer four questions, then pass the baton to some more writers so they can hold forth on the topic. It’s been a lot of fun reading some of the entries that have come before me, so I’d urge you to first check out David’s entry, then follow that back to Kim Barnes, who tagged him, and so on. Go ahead. My answers will be here when you come back. Oh, you’re ready now? Onward …

1. What are you working on?

As ever, I have my hands in several pots at once. My forthcoming novel, The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter, is set for a September 30th release, so I’m busy doing several things in preparation for that: revamping my website, writing essays for blog visits the week of the book’s release, preparing promotional materials, etc. I also have a thriving freelance business as a copy editor and graphic designer, and those duties ebb and flow, depending on the time of year and my writing commitments.  About that last bit … Earlier this year, I got well down the road on what I hope will be the third novel featuring Edward Stanton, the character at the heart of my novels 600 Hours of Edward and Edward Adrift. That project, I’m sorry to say, is on hiatus while I give it some more time in the incubator that is my strange brain. There’s not much more I can say about that without saying entirely too much. And that also pretty well describes what I can reveal about the idea that has pushed to the forefront of my thoughts. To speak of it at any length now would tarnish the energy that is causing the idea to peck insistently at my frontal lobe, demanding to be released onto the page.

About that last bit … Earlier this year, I got well down the road on what I hope will be the third novel featuring Edward Stanton, the character at the heart of my novels 600 Hours of Edward and Edward Adrift. That project, I’m sorry to say, is on hiatus while I give it some more time in the incubator that is my strange brain. There’s not much more I can say about that without saying entirely too much. And that also pretty well describes what I can reveal about the idea that has pushed to the forefront of my thoughts. To speak of it at any length now would tarnish the energy that is causing the idea to peck insistently at my frontal lobe, demanding to be released onto the page.

2. How does your work differ from others of its genre?

I’m not even sure I have a genre. My work falls into that great, wide grouping I’d call “contemporary fiction.” It occasionally gets labeled as literary fiction, but I’m entirely too self-effacing to call it that. What I try to do is write good stories—stories with big hearts that reflect the many dimensions of being human. I figure if I achieve that, I can leave it up to the marketing geniuses to find the audience, which is really what we’re talking about when we invoke the word “genre.” I will say that life is both comedic and dramatic, and my work often incorporates both. It also leans heavily to one side or the other, depending on the story. But I’ve never sat down and said, “I’m going to write a funny story” or “I’m going to write a harrowing story.” It just sort of happens.

3. Why do you write what you do?

This is the cop-out answer of all cop-out answers, but it’s also the truth, so I’ll have to go with it: Because I can’t imagine writing anything else. Back in the early 2000s, when I worked at a big newspaper in California, I got into a minor argument with one of my co-workers, a dispute so insignificant that I can’t even remember the spark or my particular position. But I’ve always remembered what that co-worker said to me, as she contended that I was missing her point by a wide margin. “Goddammit, Lanky,” she said, invoking a nickname that didn’t make the trip with me to Montana, “you get people more than anybody I know. Why don’t you get this?” It’s stuck with me because when I finally wrote my first novel, in my late thirties, I realized what she meant. I write to understand. I write because I want to know why people do the things they do—or, just as vexing, why they don’t do what they should—and if I can’t always find satisfactory answers out in the world, I can search for them on the page. That’s why I write. So thanks for that, Amy.

4. How does your writing process work?

With the exception of 600 Hours of Edward, which came in a 24-day writing torrent and was conceived in a single day, I’ve found that what I need more than anything is time. Time to develop an idea. Time to let it sink into my head and marinate a bit. Time to walk around, not really paying attention to my surroundings, while I build out possible avenues to explore. Time to let the idea push aside every other notion that’s competing for space in my head. Once it starts pressuring me to get out, that’s when I know it’s time to write. And when I commit to a project, I’m an everyday writer. Usually in the morning, after my wife goes to work. Sometimes late at night, if other duties have taken up too much of my day. I’m not a word count guy or a time clock guy. I work for as long as I’m staying engaged, and as long as I feel like I’m writing in a tight, active, interesting way. If I feel the wheels go wobbly, I’ll switch gears and work on something else, or duck out for lunch with my Dad. Whatever.

I try to leave each day’s work in a place where I can pick up the thread the next day, and I begin each writing session by editing what I wrote the day before. That serves to drive me back into the narrative and bring the words back to the fore. Because of this discipline, I tend to draft rather quickly—three months at the most, generally. Of course, at that point I’m not nearly done. Revisions, my favorite part of the process, can take months more, depending on how cleanly I captured the story the first time around.

For me, it all comes down to vision—how well I see the way forward. I’m not talking about knowing every twist and turn; I never know that. I’m talking about feeling the pulse of the story and knowing that if I keep pushing ahead, good things will happen. When I turned in my initial draft of Hugo Hunter, my editor read it and sent it back to me with some suggested alterations. As soon as I talked to him, I could clearly see (a) he was right and (b) how I could get there. He asked me how long I’d need. I said, “Fewer than twenty days, I think.” He didn’t believe me, but that’s how it came to pass. I’m fortunate when it works out that way.

So that’s it from me. Please check out these writers’ thoughts on their processes:

The author of Adventures in Yellowstone and the forthcoming The Yellowstone Stories is a fifth-generation Montanan and, like me, a lapsed newspaperman. His work has appeared in such publications as the Big Sky Journal, Montana Quarterly and the Pioneer Museum Quarterly.

Helene is a writer and entrepreneur. Her wide-ranging interests include pottery, knitting, travel, cooking, running and painting. She also claims me as her favorite author, but you should give her a pass on that.

The Billings, Montana-based writer holds forth at a blog called Don’t Quit Your Day Job, even though he did. He’s the author of the science-fiction books Rhubarb and Legitimacy, two books that fill me with considerable cover envy.

June 5, 2014

Waiting for the wait to stop*: My writing process

*—any time I get to quote a song by Joe Pernice, I’m gonna do it. Fair warning.

Thanks to a nod by David Abrams, author of the fine comic war novel Fobbit and an all-around awesome fellow, today I’m going to take part in a blogging exercise that has been making the rounds for a while now. I’ll chat a bit about the highly unscientific, often maniacal, regularly confounding process that leads to the writing I do. The idea here is to answer four questions, then pass the baton to some more writers so they can hold forth on the topic. It’s been a lot of fun reading some of the entries that have come before me, so I’d urge you to first check out David’s entry from last week, then follow that back to Kim Barnes, who tagged him, and so on. Go ahead. My answers will be here when you come back.

Oh, you’re ready now? Onward …

1. What are you working on?

As ever, I have my hands in several pots at once. My forthcoming novel, The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter, is set for a September 30th release, so I’m busy doing several things in preparation for that: revamping my website (the version you’re looking at today will soon go away), writing essays for blog visits the week of the book’s release, preparing promotional materials, etc. I also have a thriving freelance business as a copy editor and graphic designer, and those duties ebb and flow, depending on the time of year and my writing commitments.

About that last bit …

Earlier this year, I got well down the road on what I hope will be the third novel featuring Edward Stanton, the character at the heart of my novels 600 Hours of Edward and Edward Adrift. That project, I’m sorry to say, is on hiatus while I give it some more time in the incubator that is my strange brain. There’s not much more I can say about that without saying entirely too much. And that also pretty well describes what I can reveal about the idea that has pushed to the forefront of my thoughts. To speak of it at any length now would tarnish the energy that is causing the idea to peck insistently at my frontal lobe, demanding to be released onto the page.

Earlier this year, I got well down the road on what I hope will be the third novel featuring Edward Stanton, the character at the heart of my novels 600 Hours of Edward and Edward Adrift. That project, I’m sorry to say, is on hiatus while I give it some more time in the incubator that is my strange brain. There’s not much more I can say about that without saying entirely too much. And that also pretty well describes what I can reveal about the idea that has pushed to the forefront of my thoughts. To speak of it at any length now would tarnish the energy that is causing the idea to peck insistently at my frontal lobe, demanding to be released onto the page.

2. How does your work differ from others of its genre?

I’m not even sure I have a genre. My work falls into that great, wide grouping I’d call “contemporary fiction.” It occasionally gets labeled as literary fiction, but I’m entirely too self-effacing to call it that. What I try to do is write good stories—stories with big hearts that reflect the many dimensions of being human. I figure if I achieve that, I can leave it up to the marketing geniuses to find the audience, which is really what we’re talking about when we invoke the word “genre.” I will say that life is both comedic and dramatic, and my work often incorporates both. It also leans heavily to one side or the other, depending on the story. But I’ve never sat down and said, “I’m going to write a funny story” or “I’m going to write a harrowing story.” It just sort of happens.

3. Why do you write what you do?

This is the cop-out answer of all cop-out answers, but it’s also the truth, so I’ll have to go with it: Because I can’t imagine writing anything else. Back in the early 2000s, when I worked at a big newspaper in California, I got into a minor argument with one of my co-workers, a dispute so insignificant that I can’t even remember the spark or my particular position. But I’ve always remembered what that co-worker said to me, as she contended that I was missing her point by a wide margin. “Goddammit, Lanky,” she said, invoking a nickname that didn’t make the trip with me to Montana, “you get people more than anybody I know. Why don’t you get this?” It’s stuck with me because when I finally wrote my first novel, in my late thirties, I realized what she meant. I write to understand. I write because I want to know why people do the things they do—or, just as vexing, why they don’t do what they should—and if I can’t always find satisfactory answers out in the world, I can search for them on the page. That’s why I write. So thanks for that, Amy.

4. How does your writing process work?

With the exception of 600 Hours of Edward, which came in a 24-day writing torrent and was conceived in a single day, I’ve found that what I need more than anything is time. Time to develop an idea. Time to let it sink into my head and marinate a bit. Time to walk around, not really paying attention to my surroundings, while I build out possible avenues to explore. Time to let the idea push aside every other notion that’s competing for space in my head. Once it starts pressuring me to get out, that’s when I know it’s time to write.

And when I commit to a project, I’m an everyday writer. Usually in the morning, after my wife goes to work. Sometimes late at night, if other duties have taken up too much of my day. I’m not a word count guy or a time clock guy. I work for as long as I’m staying engaged, and as long as I feel like I’m writing in a tight, active, interesting way. If I feel the wheels go wobbly, I’ll switch gears and work on something else, or duck out for lunch with my Dad. Whatever. I try to leave each day’s work in a place where I can pick up the thread the next day, and I begin each writing session by editing what I wrote the day before. That serves to drive me back into the narrative and bring the words back to the fore.

Because of this discipline, I tend to draft rather quickly—three months at the most, generally. Of course, at that point I’m not nearly done. Revisions, my favorite part of the process, can take months more, depending on how cleanly I captured the story the first time around.

For me, it all comes down to vision—how well I see the way forward. I’m not talking about knowing every twist and turn; I never know that. I’m talking about feeling the pulse of the story and knowing that if I keep pushing ahead, good things will happen. When I turned in my initial draft of Hugo Hunter, my editor read it and sent it back to me with some suggested alterations. As soon as I talked to him, I could clearly see (a) he was right and (b) how I could get there. He asked me how long I’d need. I said, “Fewer than twenty days, I think.” He didn’t believe me, but that’s how it came to pass. I’m fortunate when it works out that way.

So that’s it from me. Please bookmark the following blogs and check out these writers’ thoughts on their processes next week:

The author of Adventures in Yellowstone and the forthcoming The Yellowstone Stories is a fifth-generation Montanan and, like me, a lapsed newspaperman. His work has appeared in such publications as the Big Sky Journal, Montana Quarterly and the Pioneer Museum Quarterly.

Helene is a writer and entrepreneur. Her wide-ranging interests include pottery, knitting, travel, cooking, running and painting. She also claims me as her favorite author, but you should give her a pass on that.

The Billings, Montana-based writer holds forth at a blog called Don’t Quit Your Day Job, even though he did. He’s the author of the science-fiction books Rhubarb and Legitimacy, two books that fill me with considerable cover envy.

April 4, 2014

I’m looking at you, Bozeman, Missoula, Ronan, Dillon

I always have a good time reading in Ronan. This is from my 2010 visit there to read from my debut novel, 600 HOURS OF EDWARD. (Photo by Jim Thomsen)

For various reasons owing mostly to a career that I no longer have, I didn’t do much traveling with Edward Adrift when it came out last year.

Starting Tuesday, April 8, I aim to rectify that. I’ll be hitting the road for a four-gig tour of western Montana independent bookstores and libraries, where I’ll read from and talk about Edward Adrift and will even include a sneak-preview reading from my next novel, The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter (release details still to come). Here’s where I’ll be, hoping to see old friends and make some new ones:

Tuesday, April 8: At the Country Bookshelf, 28 West Main Street, Bozeman, MT. 7 p.m. www.countrybookshelf.com

Wednesday, April 9: At Shakespeare and Co., 103 South 3rd Street West, Missoula, MT. 7 p.m. www.shakespeareandco.com

Thursday, April 10: At the Ronan Library District, Ronan, MT. 6:30 p.m. www.ronancitylibrary.org

Friday, April 11: At The Bookstore, 26 North Idaho Street, Dillon, MT. 5 p.m. www.dillonbookstore.com

March 28, 2014

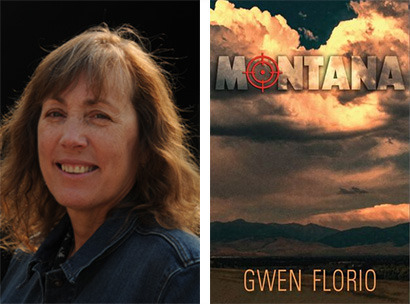

Q&A: Gwen Florio

Newspaper people exist in a small world, which is how I felt as though I knew Gwen Florio even before I met her. We spent a number of years working for the same newspaper company. She was at the Missoulian, I was 350-some miles east at The Billings Gazette. She was a reporter. I spent most of my time on the copy desk, and editing her stories was how I grew familiar with her and her writing. When she chucked the newspaper career and became a full-time novelist, I can’t say I was surprised. I was doing the same thing.

Her first novel, MONTANA, let readers get to know Lola Wicks, a seasoned foreign correspondent who has been pulled back to the States against her wishes. Told to take some time off, she heads to Montana and lands in the middle of a murder mystery that is very personal to her.

Next up is DAKOTA, which puts Wicks back in the cross-hairs, this time in the booming Bakken oil formation. The new book releases March 21 from The Permanent Press.

In the midst of an active touring schedule, Florio was kind enough to answer a few questions …

Q: DAKOTA comes on the heels of MONTANA, a novel that has garnered fine reviews and introduced us to journalist Lola Wicks. What do you want people to know going into this one?

Q: DAKOTA comes on the heels of MONTANA, a novel that has garnered fine reviews and introduced us to journalist Lola Wicks. What do you want people to know going into this one?

That Lola is back, and as bullheaded as ever. When she gets her teeth into a story, she can’t let go, even when specifically warned away. It takes place amid the social upheaval of North Dakota’s Bakken oil fields, a situation I found absolutely fascinating.

Your protagonist is a female journalist. You, of course, were a longtime, award-winning newspaper reporter. The inevitable question: How much of Lola is you?

One of the great pleasures about writing fiction is that you can create a protagonist who shares some of your own characteristics, and then make her so much better! For instance, I was never a full-time foreign correspondent. I just “parachuted” into situations for a few weeks and then came home. Lola is the seasoned correspondent I wish I’d been. As I’ve often remarked, she’s also taller, thinner and younger, which annoys the heck out of me. Sometimes I think that’s why I put her in such awful situations.

Why do you think so many reporters make the successful transition to fiction? And what caused you to think, OK, it’s time for me to leave the beat behind and focus my energy on books?

Because they got tired of a regular paycheck and health benefits? Seriously, most reporters I know are avid fiction readers, so it makes sense that they’d like to write novels. And, because they write daily, the prospect of writing a novel is probably not as daunting to reporters as to other people. Finally, that crack about a paycheck and health insurance actually was part of the impetus to finally give fiction a full-time go: As the field of journalism became more and more tenuous, with near-daily reports of layoffs and other cost-cutting measures at newspapers, it seemed silly to hang on to a job I felt as though I inevitably were going to lose, anyway. I also waited until I had a two-book contract before I left, so the leap wasn’t completely quixotic.

You’ve been traveling a lot and meeting readers in support of your first book. What has been the best moment you’ve experienced? Did anything surprise you?

A couple of things: Traveling around Montana, something the day job left little time for. Giving readings and doing research is a great way to see the state. Last summer, we drove out to the Bakken for research on DAKOTA, and then back along the whole Hi-Line, something I’ve wanted to do ever since I moved to Montana. It was worth the wait. Even more, it’s been great to connect with people who love books, and with other writers. I’ve met people, like you, whose work I’ve admired from afar. That’s much fun. The biggest surprise? The fact that readings in the smallest towns sometimes attract the biggest and most engaged audiences. That makes it doubly fun for me, because the smaller towns are the places I most enjoy going.

What led you to writing as a career?

I’ve always loved to read. I grew up in a very rural area without a lot of other kids around, so I just read and read and read. I was an English major in college (more reading) and got into journalism when my dad not-so-subtly suggested that I might need to channel all of that reading and writing into a job.

OK, you’re at home, working on a manuscript. What does a day of work look like?

I’m at my laptop no later than 9 a.m., a big change from when I used to slide into work a minimum of 10 minutes late each day (we won’t talk about all the unpaid overtime each night). When I had the day job, I shot for 500 words a day. When I first started writing full time, I upped that to 1,000, and recently started working on 1,500 to 2,000 a day. A daily total is important to me—it harkens back to my daily journalism deadline, so feels familiar, and it also helps me get through the hell of a first draft. Afternoons are for blogging (not often enough), setting up readings, and keeping track of the surprising amount of minutiae that goes along with this business. One more thing: I have a rule about not writing in my jammies. I have to be showered and dressed, more or less presentably, before I start work. Finally, when I’m deep into revisions, I often work well into the night. I’m not much fun to be around then.

How do you hone a project? Do you have a critique group or trusted early readers?

I’ve been a member of two terrific writing groups (Rittenhouse Writers’ Group in Philadelphia and 406 Writers in Missoula) over the years, and they’re really helpful, especially with short stories. Novels are a different animal, and I’m still feeling my way with them. On the advice of my agent, I hired an outside editor for MONTANA (Judy Sternlight; can’t say enough good things about her) and turned to her again for DAKOTA, and hope to do so with subsequent novels. I’m also a member of an online group of four women formed after last year’s Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers convention in Denver. That’s really helpful.

What lies beyond DAKOTA? Can you give us a glimpse into your next project?

WYOMING! And then, ARIZONA and UTAH. Seriously, my publisher did me a favor when he named the book MONTANA by giving me a theme of sorts. As long as people, please God, are interested in following Lola around, I’m going to keep sending her from one state to the next. It’s fun trying to figure out a plot that’s thematic to each place.

If you’re not writing, what interests fill your time?

For many, many years, writing took up all my spare time. I’m still getting used to the fact that I actually have personal time on evenings and weekends now. For starters, I’ve gotten reacquainted with my sweetie, a huge benefit. He comes along on my book research trips, so we’ve had fun exploring remote parts of North Dakota and Wyoming. I started running a couple of years ago, completing one marathon and three half-marathons so far. If my knee cooperates, I’ll shoot for at least one half-marathon this year. The training gets me outdoors on trails around Missoula, something that—even in the worst of weather—I just love. And, I can’t spend too much time in Glacier. Oh, and reading. Lots of reading. Never enough time for that.

March 16, 2014

Plotting vs. pants-ing

With all necessary apologies, I’m going to talk a bit here about process. If that topic bores you as much as it does me (ordinarily), you won’t hurt my feelings by going somewhere more fun on this great wide Web.

You might like this place better.

If you’re sticking around, you’ve been warned, etc., etc.

Some months ago, I started a new manuscript. In short order, about eight double-spaced pages in, I put it down. Extensive work on another project—a partial teardown-and-rebuild, then a developmental edit—interceded, and I figured I could get back to the new manuscript when things were less frantic around here.

That opportunity came a week ago, and I’ve spent several hours with it every single day. In that time, the manuscript has grown: from eight pages to 102 (as I write this—with more writing scheduled for later tonight, who knows where it will be when I succumb to sleep).

This is unusually fast progress for me. In fact, it’s happened only two other times, and both of those were stories involving the same main character who is occupying my time now. I’m not trying to be coy here. It’s another Edward story.

I can’t explain why this character and his situations reveal themselves to me in such an expeditious way, when everything else can be such a struggle (see: my earlier mention of the teardown-and-rebuild). I can’t explain it, but I also don’t question it. To do so would show a lack of gratitude, and I’m endlessly grateful.

Part of the reason stories can be slow in coming lies in how I approach the work. I’ve tried plotting, but it doesn’t work well for me. I end up deviating from the plot, and if I’ve taken the time to write out notes before beginning the story, I feel compelled to revise my notes, which means I’m working on multiple documents simultaneously, and all of this serves to drive me out of the mental place where I can just let the narrative come as it may. If all of this sounds hopelessly artsy-fartsy (technical term), please believe me that I used to think so, too, long before I wrote fiction and I thought that writers who droned on about process were in danger of disappearing into their own nether regions. Now I’m one of them. Whatever.

What does work for me is putting a character on the page, giving him/her a nudge, and then following wherever he/she goes. Yes, sometimes those travels contradict the sense and sensibility of something that has come earlier, but hey, that’s why we revise. Yes, sometimes those journeys hit a dead end and the story dies. And yes, sometimes those characters travel to a place where the story is completed, but in a way that’s so unsatisfying that I wouldn’t dream of letting anyone else read it.

A friend of mine, novelist Taylor Lunsford, made a simple declaration when we were talking about this: “You’re a pants-er.”

“Huh?”

“You fly by the seat of your pants.”

Well, yeah.

So there it is. I’m a pants-er. I’m not going to apologize. I’m not going to dedicate myself to reform. I’m just going to grab every available minute until this story spins itself out.

I can’t wait to see what happens next.

January 12, 2014

Take me back to Sotogrande

On Jan. 9, the last full day of my visit to my hometown in Texas, I made an odd request of my folks.

“Will you ride with me out to Sotogrande and see if we can find our old place?”

We have only two “old places” in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. The most notable is the house we moved into when I was four years old, where my mother and stepfather raised four kids, where they outlasted every neighbor we had until, in early 2013, they up and moved to a new place a stone’s throw from my old high school.

7025 Crabtree Lane in North Richland Hills, Texas, the house where I grew up. This photo is taken from Google Street View.

And then there’s Sotogrande, the apartment complex where my stepfather, Charles, lived when he fell in love with my mom and moved us down from Casper, Wyoming, to live with him. At that time, forty years ago, it was one of the swankiest places you could live in the cluster of humanity known as the Mid-Cities. It adjoined a nine-hole golf course, had lots of swimming pools and boasted a nice set of tennis courts. It wasn’t hard to understand the appeal to Charles, a divorcee and father before Mom and I came along.

Of course, time brings changes. I hadn’t seen Sotogrande in twenty years or so. It’s undergone a few facelifts, and the name I knew it by is now a relic, replaced by “Westdale Hills,” a change for the worse, if you ask me. It’s a little rough around the edges. A friend tells me there’s a bit of a crime problem there.

Time had gone to work on us, too. For a while, we couldn’t find the damn apartment. We drove in and out of cul de sacs. We stared at informational signs. And then, finally, something clicked for Mom. From the backseat, she said, “Turn in here,” and there it all was. On our right, the swimming pool where we whiled away summer days. Dead ahead, the sidewalk where I learned to ride a bike. And there, on the corner, the steep flight of steps to our door, No. 116.

Our cul de sac at Sotogrande. The pool is at the top of the frame. Our apartment was on the opposite corner.

Charles likes to tell a story about me from that short time we all lived at Sotogrande. In 1973-74, he was still trying to make inroads with a little boy who would come to consider him both best friend and role model. One night, he called me in for dinner, and I came shooting up the stairs and through the front door.

“What are we having?” I asked.

Charles leaned down, scrunched his nose and said, “Liver and onions.”

“Woohoo!” I said. “My favorite!”

I don’t remember this, but it’s become family lore, right along with “a guuuuumbaaaaaall machine!” (don’t ask) and “that’s not just unbelievable, that’s incredible” (really, don’t ask). As we looped through the parking lot, it wasn’t hard for me to imagine the little boy I was bounding in front of my eyes and tearing up the stairs, just another day in a life that was undergoing remarkable change in those years.

Part of that change lay in the designs my folks had for their own lives. By the end of 1974, we’d be ensconced in that three-bedroom house on Crabtree Lane. In early 1976, my sister, Karen, joined us. Another two years brought my brother Cody. Keith, the older stepbrother I’d received by way of marriage, lived with us for stretches. A neighborhood thick with kids and single-family homes made more sense than a small two-story apartment.

So why was it so important for me to see Sotogrande on this visit?

In part, it was just the character of the entire trip. I visit my part of Texas irregularly—sometimes it’s a year between visits, sometimes a year and a half, sometimes just a few months—and every time I’m back I have to account for the rapid way in which it changes. Transformation happens where I live, too, but I can deal with that, as I assimilate it day by day. When I’m in North Texas, on the other hand, I have to play catch-up. Open spaces get gobbled up and stores and houses and schools are spit out in their place. The contours of roads I thought I knew change, sometimes drastically. On this trip, I spent hours in my rental car, sometimes with a friend but often alone, looking for traces of the familiar amid transformations. Sometimes I found it. Sometimes I just shook my head and tried to remember a different, younger time.

Sotogrande, though, was more than that.

You see, I have so many memories of my short time there. The first dog I loved, a stray dachshund we named Sniffer, was found there. I learned to navigate a relationship with a brother after being an only child. I saw my mom grow happy and contented. I found a man who was willing to raise me as his own flesh and blood, and let me tell you, that’s a remarkable thing.

Sotogrande gave birth to my earliest strung-together memories. Everything before it exists in whispers of recollection. I knew I loved my dad back in Wyoming. I knew he lived in Casper after we were gone. Little snippets of recall remain in my head, but they unravel quickly, and they’re out of order. Sotogrande, on the other hand, represents a real era in my life, a period both lived and remembered.

I enjoyed seeing it again.

November 23, 2013

Now available: Slump Buster

I just put up a short story, SLUMP BUSTER, in the Kindle store.

This piece originally appeared in the Spring 2013 issue of The Montana Quarterly (a publication you should read if you don’t already). When I wrote it, back in December of last year, I figured it was a one-off. I had this little idea about a broken-down boxer trying to come to grips with a bleak future.

Funny how things work …

The main character in the story, a fighter named Hugo Hunter, is now the title character of the novel I just finished, THE FALLOW SEASON OF HUGO HUNTER. No word yet on when that book is coming out, but in the meantime, you can get to know Hugo a little bit by downloading this story. It’s 99 cents in the U.S. Kindle store, and a proportional price elsewhere. If you have a Prime membership, you can read it for free. Can’t beat that.

September 25, 2013

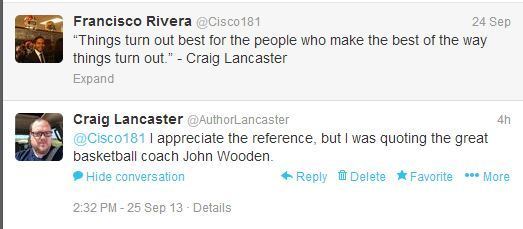

It’s a great line, but I didn’t come up with it

Something curious has happened in the past several weeks.

Three or four times now, I’ve searched for my name on Twitter—yeah, I’m that guy—and I’ve come across posts that look like this:

“Things turn out best for people who make the best of the way things turn out.”—Craig Lancaster

Uh, no. John Wooden. No, seriously, he really said it.

Because I’m such an accuracy freak—blame journalism; I’m trying to break the habit—I feel compelled to publicly set the record straight, as I did several hours ago. To wit:

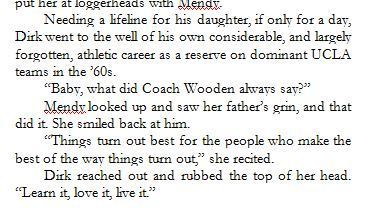

I know how this happened. I wrote a collection of short stories, Quantum Physics and the Art of Departure. I don’t talk a lot about this book, but I’m really proud of it. The first story, Somebody Has to Lose, is about a teenage basketball phenom and her coach, and the tangled mess that results when a town loses its mind over sports. The phenom’s father is, fictitiously, a former player on Wooden’s UCLA teams, and he has drilled this quote into his daughter’s consciousness. It’s a small part of a long story, but it’s obviously struck a chord. Not surprising. The original Wooden quote struck a chord with me.

Here’s what it looks like in print:

Once more, for the record:

It’s a great line.

But I didn’t come up with it.

John Wooden did.

August 28, 2013

100K

When it comes to the book business and how I comport myself, I’m a man of guiding principles:

1. Write what’s in my heart, not what I calculate to be the quickest route to sales, notoriety, etc.

2. Connect with readers, not other authors.

3. Don’t get in back-and-forths with critics. They have their role, I have mine.

4. Don’t yammer on about sales figures.

For much of my novel-writing career, still in its adolescence, No. 4 has been easy to honor. There wasn’t much to say. Beyond that, trumpeting one’s sales has generally struck me as unseemly, unless it’s for educational purposes (see J.A. Konrath, who has been transparent about how his life and career have been changed by self-publishing) or some truly remarkable threshold has been met.

I hope the latter is the case here, as I deviate from my self-imposed rigor.

Because of the vagaries of sales numbers—this month’s sales could be eroded by next month’s returns—I won’t know exactly when I cross this threshold, but sometime in the next week, I should reach 100,000 books sold since my first, 600 Hours of Edward, was originally released in October 2009.

In some significant ways, it’s no big deal. I haven’t spent a day on any of the big bestseller lists. My books aren’t released with big multimedia marketing campaigns. I haven’t managed to keep an entire publishing division afloat with any single title. And, hey, it took me four releases in almost four years to accumulate those numbers. (And that doesn’t even get into sales numbers being a poor arbiter of book quality. We’ve all known crap books that sold in crazy quantities and wonderful books that never found an audience.)

On the other hand …

Before 600 Hours came out, I never expected to sell one book, let alone 100,000. In the years since that first release, some remarkable things have happened. I’ve been able to write more books and leave my job, dedicating myself full-time to being a professional author. I find now, at 43 years old, that I am what I dreamed of being back in high school: a self-sustaining, satisfied, working-man author. That was the aim when I started. Not awards (although they’re definitely nice). Not being the toast of the tastemakers (not bloody likely, ever). I just wanted to be a guy who put in the work and made a living.

That’s the significance of the sales, that I’m there and can now dream bigger. More, that’s the significance of all the people who’ve been so kind to buy the books, read them and tell their friends. My gratitude is bottomless.

To mark the occasion and to say thank you, I’m doing some giveaways over at my author page on Facebook. Among the goodies:

The chance to lend your name to a character in the novel I’m currently writing and receive a signed first draft of it.

Signed copies of all four books.

A coffee date with me. (Obviously, if you don’t live in Billings, Montana, or Montana at large, I’ll probably just send you a coffee card, which is the better prize anyway).

Follow the link above and comment on the giveaway post on my Facebook page. That’s all it takes.

August 21, 2013

Working blue

I woke up this morning to this online review of 600 Hours of Edward.

The salient bit:

If not for the swearing it would have received five stars and been one of the best books I’ve read lately hands down. As it is I don’t feel I can recommend it to my children or friends…unfortunate.

I don’t hear this often, but I do hear it. And I feel bad every time. First, it’s a missed opportunity to bring a reader fully into my work. More than that, I hate it when my own reading experiences pull me in two irreconcilable directions, so I have no wish to leave others with that feeling. It might have been more satisfying for this reader to have hated everything about the book. It certainly would have left things less muddled.

I have a policy about not responding directly to critics in an online forum, a stance that—so far—has kept me from gaining notoriety for all the wrong reasons. That policy goes hand in hand with a general sense of gratitude I have toward those who spend time with what I’ve written and take the initiative to share their thoughts. This is walk-the-talk stuff. You can’t bask in the five-star reviews and take them as confirmation of your literary genius and then turn a blind eye to those who find flaws in your work and present their case in a coherent way.

So instead of rebutting this review—because it’s a well-presented, well-spoken opinion and thus needs no rebuttal—I’d like to instead talk about why blue language appears in my novels and why, even if I wanted to, I cannot keep it out.

The stories I write are given birth by my imagination, but the characters inhabiting them are dumped out into a world that’s very real to me. Edward Stanton, the protagonist of 600 Hours of Edward and its followup, Edward Adrift, in particular inhabits a place I know well. He lives in Billings, Montana, where I live, and shops at the Albertsons on 13th and Grand, where I shop. His house is modeled on a dwelling I once lived in, and it’s situated at an address (a made-up number on a very real street) a block away.

And in this world, bad things happen and intemperate things are said. I have an intellectual responsibility, when I write of this place, to reflect it as I find it. This isn’t something I think about overtly—there’s not a message above my computer that says “remember your intellectual responsibility.” Instead, it’s an interior compass that guides me as I go, that assesses each paragraph and each quotation and asks this fundamental question: Is this true to the story? If it is, it stays.

And let me be clear: Even gratuitousness can be true. I once spoke to a library group about my second novel, The Summer Son, and was challenged on both the language and the violence in it. The reader asked why I felt compelled to present it in such a graphic way. That novel took place against the backdrop of another world I once knew well, that of oil rig workers and their itinerant lives. My response was that I presented that world as it presented itself to me. Impasses were addressed not with the high language of a diplomat but with the raw anger of hardened men. Where language wouldn’t do, fists would. I said I couldn’t see any other way to show it. And I can’t. And I won’t. This is where differing sensibilities have to be given respect. And sometimes, as in this case, the author and the reader simply can’t find a way across the street to one another.

One last thing: The balancing factors of ugliness and crudity are grace and elegance. Just as it would be irresponsible of me to present a world where no one curses or kills someone, so, too, would it be irresponsible to show a place where the light never gets in. I’m fundamentally a hopeful guy, and so the work I do bends toward that hope. In the end, I have to think that carries more weight in the work than the battered world in which the characters live.