Waiting for the wait to stop*: My writing process

*—any time I get to quote a song by Joe Pernice, I’m gonna do it. Fair warning.

Thanks to a nod by David Abrams, author of the fine comic war novel Fobbit and an all-around awesome fellow, today I’m going to take part in a blogging exercise that has been making the rounds for a while now. I’ll chat a bit about the highly unscientific, often maniacal, regularly confounding process that leads to the writing I do. The idea here is to answer four questions, then pass the baton to some more writers so they can hold forth on the topic. It’s been a lot of fun reading some of the entries that have come before me, so I’d urge you to first check out David’s entry from last week, then follow that back to Kim Barnes, who tagged him, and so on. Go ahead. My answers will be here when you come back.

Oh, you’re ready now? Onward …

1. What are you working on?

As ever, I have my hands in several pots at once. My forthcoming novel, The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter, is set for a September 30th release, so I’m busy doing several things in preparation for that: revamping my website (the version you’re looking at today will soon go away), writing essays for blog visits the week of the book’s release, preparing promotional materials, etc. I also have a thriving freelance business as a copy editor and graphic designer, and those duties ebb and flow, depending on the time of year and my writing commitments.

About that last bit …

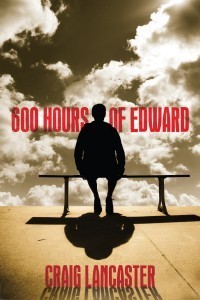

Earlier this year, I got well down the road on what I hope will be the third novel featuring Edward Stanton, the character at the heart of my novels 600 Hours of Edward and Edward Adrift. That project, I’m sorry to say, is on hiatus while I give it some more time in the incubator that is my strange brain. There’s not much more I can say about that without saying entirely too much. And that also pretty well describes what I can reveal about the idea that has pushed to the forefront of my thoughts. To speak of it at any length now would tarnish the energy that is causing the idea to peck insistently at my frontal lobe, demanding to be released onto the page.

Earlier this year, I got well down the road on what I hope will be the third novel featuring Edward Stanton, the character at the heart of my novels 600 Hours of Edward and Edward Adrift. That project, I’m sorry to say, is on hiatus while I give it some more time in the incubator that is my strange brain. There’s not much more I can say about that without saying entirely too much. And that also pretty well describes what I can reveal about the idea that has pushed to the forefront of my thoughts. To speak of it at any length now would tarnish the energy that is causing the idea to peck insistently at my frontal lobe, demanding to be released onto the page.

2. How does your work differ from others of its genre?

I’m not even sure I have a genre. My work falls into that great, wide grouping I’d call “contemporary fiction.” It occasionally gets labeled as literary fiction, but I’m entirely too self-effacing to call it that. What I try to do is write good stories—stories with big hearts that reflect the many dimensions of being human. I figure if I achieve that, I can leave it up to the marketing geniuses to find the audience, which is really what we’re talking about when we invoke the word “genre.” I will say that life is both comedic and dramatic, and my work often incorporates both. It also leans heavily to one side or the other, depending on the story. But I’ve never sat down and said, “I’m going to write a funny story” or “I’m going to write a harrowing story.” It just sort of happens.

3. Why do you write what you do?

This is the cop-out answer of all cop-out answers, but it’s also the truth, so I’ll have to go with it: Because I can’t imagine writing anything else. Back in the early 2000s, when I worked at a big newspaper in California, I got into a minor argument with one of my co-workers, a dispute so insignificant that I can’t even remember the spark or my particular position. But I’ve always remembered what that co-worker said to me, as she contended that I was missing her point by a wide margin. “Goddammit, Lanky,” she said, invoking a nickname that didn’t make the trip with me to Montana, “you get people more than anybody I know. Why don’t you get this?” It’s stuck with me because when I finally wrote my first novel, in my late thirties, I realized what she meant. I write to understand. I write because I want to know why people do the things they do—or, just as vexing, why they don’t do what they should—and if I can’t always find satisfactory answers out in the world, I can search for them on the page. That’s why I write. So thanks for that, Amy.

4. How does your writing process work?

With the exception of 600 Hours of Edward, which came in a 24-day writing torrent and was conceived in a single day, I’ve found that what I need more than anything is time. Time to develop an idea. Time to let it sink into my head and marinate a bit. Time to walk around, not really paying attention to my surroundings, while I build out possible avenues to explore. Time to let the idea push aside every other notion that’s competing for space in my head. Once it starts pressuring me to get out, that’s when I know it’s time to write.

And when I commit to a project, I’m an everyday writer. Usually in the morning, after my wife goes to work. Sometimes late at night, if other duties have taken up too much of my day. I’m not a word count guy or a time clock guy. I work for as long as I’m staying engaged, and as long as I feel like I’m writing in a tight, active, interesting way. If I feel the wheels go wobbly, I’ll switch gears and work on something else, or duck out for lunch with my Dad. Whatever. I try to leave each day’s work in a place where I can pick up the thread the next day, and I begin each writing session by editing what I wrote the day before. That serves to drive me back into the narrative and bring the words back to the fore.

Because of this discipline, I tend to draft rather quickly—three months at the most, generally. Of course, at that point I’m not nearly done. Revisions, my favorite part of the process, can take months more, depending on how cleanly I captured the story the first time around.

For me, it all comes down to vision—how well I see the way forward. I’m not talking about knowing every twist and turn; I never know that. I’m talking about feeling the pulse of the story and knowing that if I keep pushing ahead, good things will happen. When I turned in my initial draft of Hugo Hunter, my editor read it and sent it back to me with some suggested alterations. As soon as I talked to him, I could clearly see (a) he was right and (b) how I could get there. He asked me how long I’d need. I said, “Fewer than twenty days, I think.” He didn’t believe me, but that’s how it came to pass. I’m fortunate when it works out that way.

So that’s it from me. Please bookmark the following blogs and check out these writers’ thoughts on their processes next week:

The author of Adventures in Yellowstone and the forthcoming The Yellowstone Stories is a fifth-generation Montanan and, like me, a lapsed newspaperman. His work has appeared in such publications as the Big Sky Journal, Montana Quarterly and the Pioneer Museum Quarterly.

Helene is a writer and entrepreneur. Her wide-ranging interests include pottery, knitting, travel, cooking, running and painting. She also claims me as her favorite author, but you should give her a pass on that.

The Billings, Montana-based writer holds forth at a blog called Don’t Quit Your Day Job, even though he did. He’s the author of the science-fiction books Rhubarb and Legitimacy, two books that fill me with considerable cover envy.