Craig Lancaster's Blog

June 25, 2017

THE SUMMER SON: The Book That Came Back

The Summer Son, Craig’s second novel, came out in early 2011 and has been a hardy book, indeed. It was a Utah Book Award finalist, has been translated into French and German editions, and has been a steady seller for most of its life.

And now, it’s out in a newly edited second edition. The new release, put out by Craig’s imprint, Missouri Breaks Press, includes a hardcover version and full e-book versions (the original e-book was available only for Kindle).

Below, from the foreword of the new edition, Craig talks about the book and its new life.

It would be giving too much credit to publishing to call it a journey. In my experience, it’s more like a gantlet, an endurance test, the often unpleasant but necessary thing that happens once you’ve written a book and have the audacity to believe that someone not related to you might want to read it.

Some years ago, this book—my second—got published. Some very nice, accomplished people at a big, worldwide company saw some merit in it and invested the time and money to bring it into the marketplace. Press releases were written. Authors I admire were kind enough to say nice things about it. Book review outlets told their readers about it.

In its sixth and seventh months of release, when I might have expected The Summer Son to coast on that initial burst of attention, it instead tanked. In two months, it sold twenty-six copies. Total. All formats, all territories.

I figured my career, barely even begun, was a goner. I was quite certain there would never be another book. That’s what publishing can do to you. It makes you crazy with this notion that you somehow can or should take responsibility for things that are clearly not your province. Writers are healthiest, I think, when they’re doing the work to the best of their ability, interacting with their readers, and living their fuller lives outside the bubble. Publishing, on the other hand, is the bubble.

As it turned out, the summer of 2011 didn’t have the last word on The Summer Son, or on me. The book has been like a journeyman infielder; it’s persisted, done its job, and carved out a place on the team. At this writing, it’s sold upward of 70,000 copies worldwide, a respectable number. And now, in this version you’re holding, it’s coming around again.

Earlier this year, I asked the original publisher of The Summer Son, Lake Union Publishing in Seattle, to revert the English-language rights back to me. It’s a mature book, one that doesn’t really fit Lake Union’s editorial mission anymore, and I think it may yet have another chapter, so to speak.

Of all my books—there are eight now—this is the one I always thought I might do a bit differently if given the chance. Nothing big. The story is strong enough, the structure is sturdy enough, and readers have responded emotionally to it. I didn’t want to mess up anything good. I just wanted to do some scalpel work. Call it a director’s re-cut, if the cinematic metaphor works for you.

So allow me to present The Summer Son, the remake. If you stick around past the ending, there’s an essay about my family, which might give you some insights into how fact informed fiction here, and where it deviates.

I give my workshop students the following equation: memory + experience + imagination = fiction. I’ll leave it to you, dear reader, to wonder about the proportions.

Craig Lancaster

Billings, Montana

June 2017

December 11, 2016

My old Kentucky home

In January 1993, I threw an overnight bag into the backseat of my Chevrolet Citation and set out from Texarkana, Arkansas, where I lived, for Owensboro, Kentucky, where I hoped to be living soon.

I was 22 years old, on the brink of 23, into my third year as a newspaper copy editor, cocky as all hell, and pretty damn depressed. The job back in Texarkana had been sliding sideways for a while, had never really been much fun to begin with (outside of some co-workers whom I loved), and was coming to its end, one way or another.

The general look of me in the early 1990s. I’m glad the mullet is gone. I wish it hadn’t taken the hairline with it.

The previous summer, I’d butted heads with the editor and the general manager. On a slow news day, I’d built a sports-section centerpiece around Magic Johnson and his impending return to the NBA after an abrupt retirement in December 1991. The next morning, the general manager had left a clip of the centerpiece in my mailbox along with a note: “Magic Johnson is an immoral HIV carrier and our readers don’t care about him.” The editor hadn’t backed me up. I began looking for a new job almost immediately, while hanging on as best I could to the one I had. Some months of waiting and hoping had led me to that long car ride to Kentucky.

The Owensboro Messenger-Inquirer, where I’d be interviewing, was at the time one of the finest small newspapers in America—well-written, formidably staffed, beautifully designed. Pretty much everything the paper back in Texarkana was not. I was up for a job that split my duties between copy editing the sports section and the local/state section. I wanted it. Bad.

I was also hedging my bets. The same day I interviewed in Owensboro, I drove to Carbondale, Illinois, and talked to editors at the Southern Illinoisan about a job in sports. I was near certain I’d be leaving Texarkana expeditiously. I just wasn’t sure where I was headed.

Within 24 hours of my return to Arkansas, I had offers in hand from both papers. The Messenger-Inquirer offered $380 a week, the Southern Illinoisan $410. Both were well above what I was making in Texarkana, so I couldn’t and wouldn’t complain. In a display of wisdom I wouldn’t always replicate in my career, I accepted the offer in Owensboro. Never have I been so happy to tell a boss I was leaving than I was that day in Texarkana. My recollection is that he wasn’t terribly broken up by the news, either.

*****

I’m a third-generation newspaper journalist, so I know a little something about this. It’s a hard way to make a go of it in life, and it’s getting harder all the time as the business model for advertising-driven journalism dries up. I left the business in 2013, happy that I could do so of my own volition but fretting almost daily for the future of well-reported news. My hopes haven’t exactly been buffeted in the years since; see our recent presidential election and the flourishing of propaganda for a sad reminder of the fix we’re in.

Here’s what good newspapers demand of their journalists: a broad education, the ability to absorb and aggregate information, to ask pointed questions and receive informative answers, to write well quickly, and to do all of that within the strictures of daily deadlines. It’s not easy, and the pay for those skills—any one of them being much more lucrative in the open market—is historically bad. For a long time, newspapers have counted on employees having a certain love, a certain sense of duty, that supersedes the crappy pay.

For a long time, I obliged.

In Owensboro, Kentucky, as much as anywhere I ever worked, it was easy to do so.

*****

The Ohio River at Owensboro.

I lived and worked in Owensboro for about 18 months, before a (comparatively) big paycheck called me up to a bigger paper where I had only a fraction of the enjoyment.

Owensboro, you see, was special.

On the copy desk alone, there were a half-dozen colleagues right around my age, single like me, hardworking and hard-playing, the best and the brightest in that town. For most of my stay, I shared an apartment in a subdivided old mansion with one of my night crew buddies. Another one lived across the hall. Still another downstairs, directly below our unit. The one non-journalist in the place, an older lawyer, hated us. Hated our hours and our exuberance. Now, 23 years on, I’d probably be more inclined to agree with his take on things. Then? Fuck him. We were having a ball.

In a Facebook age, all of those friendships I made back then have been nurtured and recalled. Heen. Lovett. Cindy. Biv. The Toddler. Noelle. Newton. Hunter. Ben and Berry and Keith, old man riverpark, the one who keeps on keeping on.

You ever dream of returning to younger days? I do. And when I do, I usually dream of Owensboro.

*****

I tell my fiction students that there’s a formula for good novel writing. It doesn’t have anything to do with plot twists or the introduction of tertiary characters or unreliable narrators.

I tell my fiction students that there’s a formula for good novel writing. It doesn’t have anything to do with plot twists or the introduction of tertiary characters or unreliable narrators.

Here it is: memory + experience + imagination = story.

When I started writing Julep Street, back in 2013, I was thinking a lot about my memories of my time in Owensboro and the experiences I had there. In Carson McCullough, the abruptly turned out newspaper editor who follows some of his darkest impulses, I had a vehicle for my imagination. What if I’d stayed in Owensboro? I liked it there, the city and the job, and I might have hung on at the paper long enough to meet someone, settle down, buy a house. And what if I’d stayed long enough to see the newspaper business sour there, same as it has most everywhere else, and I’d felt trapped by all the things I’d been too lazy to pursue when times were better? What if I’d found myself at the end with nothing much to show for the journey?

I don’t know, man. It might have been a hell of a story.

July 23, 2016

It’s here: EDWARD UNSPOOLED

This morning, perhaps as people slept, e-readers quietly updated with Edward Unspooled, marking the official release date of my sixth novel—and the third featuring Edward Stanton and his family and friends.

Every release day is equal parts pleasure and anticipation. It’s the payoff for the long months of writing and rewriting and editing and formatting. And it’s the jumping-off point for the hope that the book will connect with the hearts and minds of readers.

Every release day is equal parts pleasure and anticipation. It’s the payoff for the long months of writing and rewriting and editing and formatting. And it’s the jumping-off point for the hope that the book will connect with the hearts and minds of readers.

This book has been especially gratifying for a few reasons. First, it showed up unexpectedly (more on that at the link above). Second, for the first time since my short-story collection was first released I decided to publish this independently. I hired an editor to work with me, a cover designer to make this book fit seamlessly with its predecessors, an e-book designer and an audiobook reader. It checked all of my creative boxes, and that was important to me.

Most important, I held true to my guiding intention: I wrote the best book I could. If this book is our first meeting, or you’ve been with Edward right along, or you’ve followed me into the other fictional crevices I’ve explored, that’s how I keep the trust with you. I give my best effort. I’m grateful for you.

Thanks for reading.

To get your copy

Paperback: Available at Amazon.com or by order through your favorite bookseller.

Signed paperback: You can buy it through my online store.

Kindle: Available at Amazon.com.

Audiobook: Coming soon through Amazon.com, Audible and iTunes.

June 2, 2016

High Plains Book Awards

The news came out yesterday that This Is What I Want is a finalist in the fiction category of the 2016 High Plains Book Awards. It’s my third finalist designation—the previous ones were for Quantum Physics and the Art of Departure in 2012 (short stories) and 600 Hours of Edward in 2010 (winner in the First Book category)—and I’m as flabbergasted and grateful as I was the first time.

Perhaps even more flabbergasted this time, since This Is What I Want came out last July and promptly…well, did not much of anything. It got some nice reviews, colleagues said some lovely things—and, again, I’m nothing but grateful—but the book just sort of settled into a corner. My wonderful friend Richard S. Wheeler, the six-time Spur Award winner and epitome of grace, gave me some advice years ago that serves me well every day. Write the best book you can, he said, and then surrender your expectations. If you’re at it long enough, books that you expect to fly will, instead, fall, and books that confound you will soar.

Perhaps even more flabbergasted this time, since This Is What I Want came out last July and promptly…well, did not much of anything. It got some nice reviews, colleagues said some lovely things—and, again, I’m nothing but grateful—but the book just sort of settled into a corner. My wonderful friend Richard S. Wheeler, the six-time Spur Award winner and epitome of grace, gave me some advice years ago that serves me well every day. Write the best book you can, he said, and then surrender your expectations. If you’re at it long enough, books that you expect to fly will, instead, fall, and books that confound you will soar.

Damned if he isn’t right. Neither This Is What I Want nor its immediate predecessor, The Fallow Season of Hugo Hunter, has found readers the way I hoped they would. But I’m at peace because they were the best books I could write when I wrote them, because they’ll be around a long time and still have the chance to connect, because I’ve been extraordinarily fortunate by any measure, because I’m not owed anything, because I still get to do this thing I love, because there will be another book, and because I’m blessed to have this book in the company of the 36 other finalists across the High Plains Book Awards categories.

The winners will be announced October 8 at a banquet in Billings. I’ll be in New England on my honeymoon.

I’ve already won.

February 17, 2016

Landscapes

Sunset in Wyoming. Photo by Elisa Lorello.

We were maybe twenty miles west of Billings, Montana, when we topped a hill and the land fell out before us, plains running in a soup bowl to the next plateau, the purple-blue sky a canopy fastened to the horizons at 360 degrees. Elisa drew in a breath and said, “I never get used to it. It never gets old.”

I knew what she meant. She’s been looking at the American West for a few months. I’ve been looking at it my whole life.

“You know what?” I said. “It never gets old for me, either.”

I wanted to tell her more, about the hundreds of miles yet to come. About the Bighorn Mountains that would grace our next gas stop, the great emptiness of Wyoming, the Front Range, Pike’s Peak, the Spanish Peaks. Colorado, a corner of New Mexico, and then the vast maw of Texas, on to the suburb I’ll always call home.

But there would be time enough for that, an unfurling at 70 or 80 mph.

I held her hand. She looked out the window. I watched the road. And everything else.

***

As we peeled off the miles ahead, we did talk about it some. She told me about growing up on Long Island, how vast space made her look for the water, because that’s the only place she ever saw it. Montana, she said, seemed unfathomably huge: the open space, the snow-streaked Crazy Mountains, the distance of the horizon. And the sky. Always the sky.

Her boundless wonder at this place that she has startlingly come to call home made me smile. I tried to tell her I had an equivalent in her part of the world, when I’d climb the stairs out of the darkness at Penn Station and alight on the sidewalk and New York—at once so familiar because of pop culture and so foreign because, well, just because—would assimilate me. Breathtaking, every time.

We batted those concepts between the seats of my Toyota, deconstructed them and examined the individual parts, and then we settled on a way of looking at our disparate perspectives.

“They’re the landscapes of our minds,” I said, borrowing and repurposing the subtitle of Ivan Doig’s This House of Sky. “Mine is here. Yours is there.”

She nodded and smiled at me knowingly. And we get to share them with each other.

***

We approached Casper, Wyoming, after dark. An hour earlier, in the waning light, I’d helped her find antelope beyond the fencelines. But now, the city twinkling, beckoning at the foot of Casper Mountain, we rode quietly even as my mind stormed. Memories—some clear, some faded, some composite—came to me, and I wondered how I’d construct the stories for Elisa and make the case that I’m both a son of this place and a fugitive from it.

I showed her my first home, a little cracker box in the roughed-up town of Mills. I lived there till I was three. I returned to it every summer through age eight. It’s a place of nostalgia and youthful longing. I’m also dead certain, as sure of this as anything ever, that the greatest gift I ever received was removal from it. I’m the son of an oil man, and a good deal of my self-image is tangled up in that. I’m also the son of a suburban mom and stepfather, and almost everything that informs who and what I am and what I do is touched by that. Casper is genesis. North Richland Hills (and beyond) is realization.

It’s hard to explain. I’ve been trying all my life, and I haven’t figured it out yet.

***

I’m trying to collect these runaway thoughts from a hotel room in Trinidad, Colorado, as Elisa lies next to me and unwinds by watching The Odd Couple. One more day of driving awaits us. More to see. More to talk about. More to take apart and put back together.

It occurred to me, as we covered the final few miles before calling a night, that these sojourns into the West are essential to how I maintain contact with the past and how I shape the dreams I send out ahead of me. I rarely feel so alive, so a part of the world, so connected to my country as when I sit quietly and take it in.

What a privilege to see it, through my own eyes again and through hers for the first time.

February 9, 2016

Duaine’s Last Rites

This article originally ran in the Winter 2015 edition of the Montana Quarterly, a magazine with which I’ve had a long association, first as a frequent contributor and now as a member of the masthead (design director). If you’re a Montanan (present or in absentia), love Montana, or are simply interested in the culture and issues of the American West, I highly recommend that you become a subscriber. It’s a great magazine.

IT’S MID-OCTOBER 2014, and in my grief over a love gone bad, I’ve pointed my car west, toward Seattle. I’m headed there because my best friend has told me to come, using the kind of language you reserve for someone you care about when you don’t recognize him anymore and are scared of what he might be thinking. “Goddammit, just get in your car and come here,” he’s told me, and so that’s what I’m doing.

It’s late morning, and I’m west of Spokane, about to lurch into the hypnotic sameness of central Washington, when I remember the name of a town I’ve only read about, the resting place of an uncle I never knew, a connection to the father whose story I’ve spent much of my adult life trying to reconstruct.

I pull over, and I punch “Creston” into my GPS program, and the satellites tell me I can get off at the next exit and start working my way north and east. A few miles ahead, I leave the interstate and make my way into the lonely corners and igneous-rock outcroppings of northern Washington.

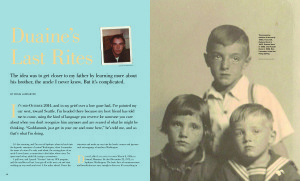

The Lancaster children in the early 1940s. From left: Delores (1937-2000), Duaine (1936-1972) and Ronald (1939-).

DUAINE LEROY LANCASTER was born March 8, 1936, in Conrad, Montana. He died December 22, 1972, in Spokane, Washington. The basic facts of commencement and benediction are easy enough to discover. It’s everything in the middle—who he was, what he sounded like, whether he was generous or mean, if he preferred dogs or cats—that’s harder to get at.

His younger brother, my father, likes to tell of the time he smashed Duaine in the face with a two-by-four, a stealth attack undertaken while Duaine’s hair was being cut by their mother. When I ask Dad why he did it, he says, matter-of-factly, “Because he rubbed cow shit in my face.” It’s a funny story only if you imagine it as a cartoon, and only if you don’t know the larger context. The young lives of Duaine and Ron Lancaster, and of their sister, Delores, were unspeakably harsh. Their stepfather, Dick Mader, kept them in line with beatings. I’ve heard the story from a cousin about Dad showing up on her doorstep, his back flayed by Dick’s whip, on one of his many unsuccessful runaway attempts. Duaine, she says, had it even worse, being the oldest.

I have one photo of the siblings together, taken in the early 1940s. There is no mirth in their faces, no childlike wonder. It’s haunting, and over the years I’ve learned enough about their lives to know why.

Duaine and Delores are gone, and Dad, now 76, doesn’t part with words or emotions easily. When I ask him what he remembers about his brother, he says, simply, “Duaine was all right.”

I take the same question to my mother, whose life has been untangled from those of the Lancasters (save me) for 42 years, and I get an answer steeped in violence.

“I remember that when we went to Kalispell for Dick’s funeral”—this would have been 1966, four years before I was born—“Ron and Duaine got into a fistfight during the wake.”

ONCE I REACH CRESTON, I’m there perhaps a half-hour. I see not a single soul. The cemetery sits on gently sloping hillside, and there the interment directory tells me that if I walk a few yards down from where I’ve parked, I should find Duaine’s plot.

Instead, I locate the neighboring headstones and an unmarked patch of yellow grass where Duaine’s resting place is supposed to be. My mind flashes on a picture I have somewhere at home, a pile of graveside roses. Dad took that, or maybe Mom did. After Duaine was struck by a panel truck while working on a survey crew in Idaho, Dad had shut down his drilling business, and he and Mom had traveled from their home in Wyoming to Spokane to keep vigil at the hospital. Weeks went by—“I learned to love crossword puzzles, sitting in that hospital,” Mom says, 43 years later—and then Duaine died. A few days after that, my folks went to Creston to see him into the earth on December 28, 1972. Near as I can tell, nobody on our side of the family has ever been back.

Now I’m here, and no one passing this spot would have any evidence of Duaine’s life, and I’ve never felt so alone.

DUAINE HAD FIVE CHILDREN—sons Ricky, Russell and Robby, and daughters Melinda and Shelly. I’d known their names for a long time; my curiosity about this unconnected family of mine far predates my spur-of-the-moment swing to their father’s gravesite. But try as I might, in this Internet age when you can learn seemingly anything about anybody, I hadn’t been able to track them down. By the time Duaine died, his family had scattered. The boys and Melinda were in Oklahoma City with their mother, Myrna. Shelly, married young and with her own life and new last name, was in Green Mountain Falls, Colorado.

And then, in a single afternoon, what and who I know changed. My Aunt Delores’ daughter Vickie came to Billings to see Dad, and we compared our meager family notes. A single surname—that of Duaine’s widow, Myrna, after her second marriage—emerged from deep in Vickie’s memories. A short online search led to Myrna, back in Montana after decades away, and a line on all of her children. My cousins. That Myrna didn’t recognize my name when I introduced myself hardly seemed notable. I knew hers and I knew Duaine’s, and thus we had a place to start our conversation.

I have much to tell these people. About how pulling at strings on the Internet has led me to other people who knew Duaine. About what I know of his family of origin, the bits and pieces I’ve put together over the past 20 or so years, and the large gaps that remain in the puzzle. About the old man who lives upstairs from me, the last living sibling of their father.

About how I’d like to know them, because they connect to Duaine, and Duaine connects to my father. About how I’m desperate to find those links, because I know that when Dad’s gone, I won’t have my father anymore, just as they haven’t had their father for most of their lives.

AFTER A THERAPEUTIC WEEK IN SEATTLE, I come home to Billings with the idea that I’ll get a headstone placed for Duaine, that perhaps I can do this one small thing to mark that he was here and he mattered. A nice man at Strate Funeral Home in Davenport, Washington, pulls the record and tells me that I can get a free headstone from the government on account of Duaine’s Marine Corps service, which I don’t even know about.

I put in the paperwork with the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, claiming Duaine on behalf of Dad, and weeks later I have more fodder for the paper trail. Duaine went into the service on November 13, 1953, as a 6-foot-tall, 165-pound private and was discharged under honorable conditions a little more than three months later, on February 27, 1954, for an undisclosed medical reason. It’s not much of a service record, but it’s enough to get him a grave marker and a certificate of commendation from President Barack Obama. The present-day events roll out slowly, as we head into winter and a new year. The headstone is ordered, and etched, and placed, and in spare moments here and there, I keep talking to Dad and digging away online.

I’VE HAD A CRINKLED, yellowing copy of Duaine’s Great Falls Tribune obituary for a couple of decades; it sits in a photo album along with the two grainy, at-a-distance shots I have of him from his adult years. It wasn’t until I received a different obituary, from someone who knew Duaine at the end of his life, that I came across a revelatory detail about our family. Among the listed survivors are the ones I always knew about and one whose story was a long time in completing. The obit I was given lists a Fred Lancaster—father to Duaine, Delores and Dad—as a survivor, but there’s no other information, like where he lived. That’s because no one knew the answer.

Fred Seath Lancaster’s grave, in Madras, Oregon.

Fred last shows up in the family story in the mid-1950s, after Dad ran away from his mother and stepfather’s dairy farm near Simms, Montana—this time for good—and reconnected with him. Fred saw Dad into the Navy and then went on his way, and it wasn’t until I did an online search of the Social Security Death Index in the late 1990s that we discovered what happened to him. He moved to Oregon, married a woman named May Belle, and died in June 1970. In December 1972, Fred was listed as a survivor of Duaine, but he wasn’t. He was already more than two years gone, and no one knew.

This kind of casual grasp of relation shows up again and again in our family. We know names, but we don’t know each other, or we know different stories. When Dad’s mother, Della, died in 1978, I felt nothing. I didn’t know her. Dad didn’t love her, except, perhaps, for the way any boy wants to love his mother, even when she shuts him out. I’ve learned enough about Della to know that she didn’t mitigate Dick Mader’s violence toward those kids, and in some cases she even abetted it. Hardship and pain bind some people; in the case of Dad and his siblings, they simply ran away from each other and toward their own destinies once they got the chance. Sentimentality wasn’t a luxury they could afford.

But then I talk to my newfound cousin Shelly on the phone, and she has warm memories of Dick and Della Mader and none of her own father. She tells me to keep her father’s certificate from the president. It wouldn’t mean anything to her, she says.

Duaine Lancaster and Roberta Bonnalie. (Photo courtesy of Debbie Henson)

IT’S JUNE 26, 2015, and I’m in Spokane again, sitting at a table in Arend Hall on the Whitworth University campus. The woman I’ve found online, Debbie Henson, works here. She’s the daughter of a woman named Roberta Bonnalie, who’s six years dead. Roberta was Duaine’s girlfriend at the end of his life.

I’ve talked to Debbie on the phone a couple of times, trying to explain who I am and why I’ve come calling about this man she knew when she was 12 years old. In person, she’s friendly, if a bit nervous, same as I am.

I ask her if Roberta loved him, and if she thinks they’d have married had Duaine lived.

“I think so, yeah,” she says.

I ask Debbie if Duaine was good to her and her older brother.

“He spoiled us,” she says. “He bought us a pool table. It’s still in my house.”

She gives me a CD, her fulfillment of my request for pictures of Duaine and Roberta. I thank her, and after some more small talk, I leave. I’m due in Creston that afternoon, to see Duaine’s place of rest one more time.

It will be late that night, hours away in Olympia, Washington, when I pop the CD into my laptop and see my uncle in a way I never have before—in full color; asleep; shirtless on a couch; opening presents with Roberta at Christmas. The moments are candid, revealing. They show a human being, not a concept.

In Duaine’s face, though, I still see the little boy from the old photograph. I see my father. I see their sister. I see their mother.

I see everything I know about them, and I’m left with gratitude for that and frustration for the fact that so much still eludes me.

WE ALL WANT CONNECTION. It’s a human desire. And in my case, with an aging father whose life has been so heartbreaking in so many ways, I feel a powerful compulsion to learn what I can while he’s still here. So many people are already gone and have taken their stories with them that I can be frantic about preserving what’s left. I try to delude myself sometimes into thinking that the effort is for him. But it is, at its heart, a selfish endeavor. I want stories that I can touch when I can no longer slip my arm across his shoulders.

I know that time is coming.

But it’s more than mere desire for connection. I try to honor my father and his family because so little is known to me, and because the vagaries of chance are so strong with us. I’m a Lancaster not because I was born naturally into it. I was adopted at birth, placed with my parents because a scared University of Washington undergrad saw no way to keep me, because Ron Lancaster and Leslie Johnson happened to be at a party on the Billings Rimrocks on the same night, met, ran away together, married, were unable to conceive a child and, late in a marriage that wasn’t very good, tried to mend their torn lives with a baby.

The Lancasters aren’t my blood. But make no mistake: they are my people.

I ROLL INTO CRESTON at midafternoon, and at once I’m turned around. Part of this is circumstance, and part is intention. Nine months earlier, after a snap decision to come here in the throes of despair, I was pulled in from the west by my GPS application, and by chance I was deposited where I wanted to be. This time, I’ve come with purpose, direct from Spokane, and I’m turned around. I’m looking on the wrong side of town for the cemetery, and at last I have to stop in at the post office. I’m happy to see a friendly face on this bright day, and I’m eager to see Duaine’s resting spot with a fresh perspective—on him, on my father, on my own life. The words “life goes on” are hackneyed; the actual going on is profound.

I ROLL INTO CRESTON at midafternoon, and at once I’m turned around. Part of this is circumstance, and part is intention. Nine months earlier, after a snap decision to come here in the throes of despair, I was pulled in from the west by my GPS application, and by chance I was deposited where I wanted to be. This time, I’ve come with purpose, direct from Spokane, and I’m turned around. I’m looking on the wrong side of town for the cemetery, and at last I have to stop in at the post office. I’m happy to see a friendly face on this bright day, and I’m eager to see Duaine’s resting spot with a fresh perspective—on him, on my father, on my own life. The words “life goes on” are hackneyed; the actual going on is profound.

Once oriented and back at the cemetery, I take my girlfriend’s hand, and we walk down the row toward Duaine. Even now, I can see it, the simple new marker with the concrete bunting.

I stand there and gaze down at the spot. I clench Elisa’s hand ever tighter. I wish for inspired words, but they come out banal instead. “Well, Uncle Duaine, here you are.” I look around. There’s no more loneliness, no more heartache. It’s a beautiful day, clear and hot, mountains hugging the horizon in the distance. If he must rest, this is a good spot.

Elisa and I walk back to the car, hand in hand. A working vacation awaits us in Olympia and Seattle and Portland. Several days later, we’ll be in Madras, Oregon, and I’ll see Fred Lancaster’s grave for the second time in my life. The story I’ve been trying to unearth will have a little more heft now. There’s still so much to discover, and I can hope for time enough to get to it.

But right now I also have my own living to do.

To see how this story looked in printed form, click here.

January 21, 2016

The education of a charmless man*

A women’s group here in Billings, one dedicated to education and scholarship, invited me to speak at their gathering this week. Here’s what I had to say:

My name is Craig Lancaster, and I’m a proud resident of Billings—it will be 10 years this June—and an active member of the community that groups like yours seek to strengthen. So I would like to say, first, thank you for inviting me here today, and second, thank you for all of your efforts toward bolstering education. As I tell you a bit about myself and my work, I hope you’ll see that we have many interests in common.

Thanks to my first novel, 600 Hours of Edward, being used in lesson plans here in Billings, I get invited a fair amount to talk in high school classrooms. When I open things up for questions, invariably this one pops up: How did you decide to write novels? And this is always a hard thing to answer, because I think the person asking it hopes that I’ll be able to identify one key mentor or one galvanizing moment that set me in this direction, and that’s simply not the case. Who I am—professionally and personally and psychologically—is the sum of my experiences and influences, along with dashes of such untamed things as serendipity and loss. Every time I write a novel, and I’ve published five now, I mine experiences, conversations, things I’ve pondered, losses I’ve suffered, my imagination. I couldn’t tell you in what proportions or how it all comes together. Indeed, it’s always a surprise when it does work. And when it doesn’t—when some idea I had simply doesn’t have the legs to blossom into a fully realized story—I’m usually not terribly upset. If anything, I’m baffled that failure to materialize doesn’t occur more often.

So this is what I say to the student who asks me the question, in a less artful way because I’m answering off the cuff rather than reading from prepared remarks. And then I add this next little bit, because I think it’s important:

Portrait of the author as a young man. Also, his sister.

I grew up in a house that had shelves, and on those shelves sat books. And I had parents who read those books, and who encouraged me to read any book I could get my hands on. From the time I was born until I could take over the chore myself, I was read to. I was shown things. I was taught how to do anything that interested me, and if something interested me that my parents couldn’t teach, they could find someone who could handle the job. Perhaps my DNA is arranged in a way that made me naturally curious, but the safer bet would be that my parents’ nurturing encouraged and rewarded boundless fascination. And I can think of no better basis for an engaged life, let alone a career as a novelist, than that.

That, my friends, is education where the rubber meets the road. It has nothing to do with getting up, eating your breakfast and carrying your books off to school. It’s being geared toward lifelong learning. There’s not a day that I fail to be thankful for having the parents I did, who pointed at the horizons and told me I could chase any of them.

Now …

In my mid-40s, while still being buoyantly grateful for all of that, I’ve also had a hard reckoning with how privileged I’ve been. I was born into a middle-class, educated family that was able to pass those benefits on to me. I’ve never wondered where my next meal is coming from—obviously!—and never dealt in any serious way with poverty. I was born white and male, which in this country is pretty much two-thirds of the cultural trifecta. None of this requires my apology or guilt, but it does command my attention to the fact that I’ve had a relatively easy go of it. When I moved into adulthood, I did so with an education, career prospects and a built-in support system, and thus my inevitable failures have been mostly fleeting and easily recovered and learned from.

When I think about education today, I wonder about and worry for those who start from a disadvantaged place. Our history as a nation tells us that education is the great leveler and the most reliable means of movement from one economic class to another. So how do we get access to education for those who need it most, those who didn’t grow up surrounded by books, who aren’t sure what they’re eating later today, whose families don’t support their dreams—indeed, those who might not have families at all, or who might not even see in their lives a reason to dream? When I was a child, I took a big bite out of the public education that my community provided. My time in college was spent in an era when I didn’t have to mortgage my future earnings to attend a university. I don’t have the expertise to advise anyone on how to improve education and expand opportunity; I’m not in that arena, fighting that good fight. My participation is at the resident level. I vote for school levies. When an English teacher here in town asks me to come talk to her kids, I do it. Because you either support the culture you wish to live in or you don’t. There’s no in-between.

My interest in this isn’t purely civic-minded, mind you. There’s a lot of selfishness involved. I write books as my primary source of income. I hope to write more, and I hope to see them published and read. And while I have artistic notions about what I do, I also have purely financial ones. A diminished reading public would, at some juncture, translate into a diminished appetite for what I do, and I would have to find something else.

So, please, allow me to say something on behalf of what I do and why I do it. From the earliest age I can remember, writing was something I knew I wanted to do, in some form or another. I’d be loath to call myself a natural—the more I do this, the more I see my flaws rather than my strengths—but the orderliness of words and sentences and paragraphs always made intuitive sense to me. The rhythms of language, the inexplicable ways of American English spelling—these things enchanted me.

As I grew up and moved outside my comfort zones—other cities, other states, other friends—I began to see the power of stories. This happened first as a journalist, where I took seriously Finley Peter Dunne’s observation that newspapers “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” In my late thirties, I embarked on my career as a novelist, where I try to capture everyday people in crisis or transition, where the suggestion of future change is perhaps more important than the actual demonstration of it. Destinations bore me. Journeys, on the other hand, thrill me. And what I learned from writing fiction is that I could take my own questions and hesitations—whether about relationships or the better manner of living or God or anything else—and work them out on the page. That other people could then read those words and find their own stories or provoke their own questions. This is powerful stuff. And it has happened, fundamentally, not because I write, but because I read. Because I’ve always read, or always had someone who read to me. That’s where it started. That’s where I find fuel even today. And it’s where I’ll replenish myself tomorrow.

*—thanks, and perhaps apologies, to Blur.

January 1, 2016

Onward into 2016

Most years at this time, I write a little piece in this space about the year gone and the year ahead. Call it a natural byproduct of the job; putting things into some kind of perspective—good, bad or otherwise—is what I do.

The problem today is that 2015 was just too big, too transformative, to distill into something appropriately compact. So I’d like, instead, to focus on a singular moment that I think was both the undeniable low point of the year and the point at which it all began to turn.

It was early March, and I’d gone to my regular appointment with my counselor, Jane, whom the world would lose just a few months later. The depths to which I’d sunk were evident on my face, and I brought along a dear friend as a witness, someone who could tell Jane that I really wasn’t as crazy as I felt.

Jane didn’t need any such affirmation. She took one look at me and said “This is a very big day for you.”

Indeed, it was. That afternoon, all the things we’d been working on together began to fall into place. I started to see how the boundaries I’d always eschewed could actually bring order to my life and funnel me toward the outcomes I valued. (For more on boundaries—what they are and how they work—allow me to commend to your attention this article by Mark Manson. It’s powerful stuff.) I learned how to speak up for the things I need, and how to keep from steamrolling other people and their boundaries. Some weeks later, when the better tools for living were firmly entrenched, I said to Jane, “How stupid I am that I couldn’t have figured this out on my own?” And she said something I’ll never forget: “Given what society demands of men, you couldn’t have possibly known until you were in your forties.” In other words, when I’d had the wreckage of a career and a marriage behind me and finally came around to the notion that maybe there’s a better way.

There’s something deeper, for all of us, than work and productivity and the overt roles that get imposed by social order. Jane helped me find that deeper something, and things rolled out from there. I stabilized my life. I found love again. I began to envision what I’d like to do in the days I have left, while leaving plenty of room for the vagaries of life that make it so interesting. I’m certainly not saying that I’ve found the secret to flawless living. Shit, no. I make a lot of mistakes. In the past year, I torpedoed some friendships as I tried to find my footing after divorce. I wish I hadn’t been so clumsy and stupid. But I also needed to be clumsy and stupid as I tried to find my way. It’s a hard thing to untangle.

Still, as I bid you a happy New Year, I’m tacking in the right direction. I see the road more clearly. I’m trying to live in gratitude and generosity.

Thanks for reading.

October 10, 2015

Connie Sullivan, November 1, 1948-September 30, 2015

My best friend’s mother died. I was fortunate to know her and love her as if she were my own. Before she left us, Connie asked me, through her daughter Cass, to deliver her eulogy. I’ve had no greater honor in my life, and no honor I so fervently wished I wouldn’t have to accept. I share the eulogy here because everyone should have been as blessed as I was to know and love her.

* * * * *

I’ve been considering this day for a while now. In some small way since Connie got sick and we learned it was terminal, although it was hard to imagine such an occasion a few days after her diagnosis, when Connie was sitting in my living room, drinking beer and eating food and futilely cheering on Manny Pacquiao in the latest fight of the century. I’ve considered it in bigger ways since her daughter Cass brought me to my knees by asking me to do this. And although in the days since we lost Connie my heart has occasionally been troubled and my memories are at a sometimes painful pitch, I can’t see my way clear to being entirely solemn about this. I’d like to talk today about Connie and about what she meant to us, and I’d like to do so in the manner she favored. Directly. Honestly. With love and humanity and realism, and maybe just a bit of cheekiness.

Because isn’t this just the way life plays both ends against the middle? Here we are, in loving congregation and shared sorrow, wondering what can possibly be fair about giving her back to the universe now, when so many of us have so much time left to miss her. It’s hard not to think that way, hard not to wonder how she could be so full of joy and life and energy and then be gone. That, of course, is vanity. Selfishness. And I believe Connie would tell us so. Still, we need not apologize for it. We’re here on this mortal coil, and that’s what we do with the human capacity we’ve been given. We look at the clock and take measure of what time it is, and we fixate on whether we’re getting our fair share of whatever it is we think we deserve. Our sweet Connie has been given release beyond time and want. May God bless her. And may God have mercy on us.

A handful of times in my life, I’ve met someone and known, in that very moment, that I’d walk the path ahead with her until one or both of us left it. It happened the first time I met Cass Sullivan, who was my BFF before I even knew what the hell a BFF is. I mean, WTF? And it happened again when I met Cass’ mama. In Connie, and in her husband, Pat, I found many of the reasons my friend Cass is such an extraordinary soul, and I found so much more than that. I came to love Connie in a way that feels very much like the love I hold for my own mother.

On Connie’s last big night on the town, I sat next to her at the Rex. Cass and Terri and Holly and Uncle Mick and Aunt Janna formed a cocoon around her, while Uncle Joe played the piano nearby. We drank beer, as would be expected of that particular crowd. Connie leaned in and said she had one thing she wanted me to convey when the time came. This, by the way, was something that came to mark her final days with us: list-making and instructions and thank-yous and ends neatly tied together. She didn’t want to leave anything undone.

So Connie leans over, and I lean over to meet her with my selfish wish that I’d never have to tell you about this. She says, “Be sure to let them know that one of the things I’m proudest of is being an activist in the Sixties.” She said that horrible spring and summer of 1968, when we lost Martin Luther King Jr. and RFK to assassins’ bullets, pointed her toward social justice. I suspect it’s no accident that this coincided with her meeting Pat and starting a family. Connie wasn’t a sloganeer or a billboard for her convictions. She just lived them, and she and Pat raised up a family marked by that same independence of thought and generosity of spirit. Connie was the kind to make a difference in her own time and in the decades to come.

Connie took another draw on her beer and then she added something. She didn’t want me to make this message overtly political and alienate anybody. (Full disclosure: As she said this, she used a very bad word to describe folks of a certain political persuasion—not yours, so relax—and then she laughed, and what could a guy do but laugh with her?) Alienation wasn’t her thing, anyway. She lived right and true, and she didn’t leave damage in her wake. To know her was to know where she stood, with no margin for misinterpretation, and to do so while having your own space to stand. That, my friends, is human dignity both exercised and conveyed.

In Connie’s final days, we all had to grapple with the idea of going on without her. On this, I’m going to speak only for myself, as I wouldn’t presume to speak for anyone else. In parting, she offered even more gifts from a life abundant in them. Whether it’s a failing of spirit or intellect, I’ve been around a long time without coming to peace with what I believe about what lies beyond this life. Connie, I think, pointed in a direction I can get behind. In her waning hours, she spoke of those who, I believe, gathered at the gate of the hereafter and beckoned her in. Her mother. Her son-in-law, Jimmy, whom she well loved. She spoke of flowers and light, and I believe she let the rest of us know that it was going to be OK, that she was headed somewhere filled with love and comfort. I believe that’s true. I believe it’s the only explanation that brings sense to the whisper of time we spend here. What I have now, and perhaps didn’t have before, is faith. So thank you, Connie, for that. The only way to know for sure is to take the trip, and we all bought our ticket when we arrived. May we all someday find it to be so, just as surely as we have faith that Connie has already alighted to such a place.

Here’s what I know for certain: We—that is, the physical us—are all the same things, moondust and a handful of ordinary elements. We share atoms with everything and everyone who has ever been. In that sense, there’s a certain comfort that Connie, and anyone we’ve ever known or loved, has never really left, and can never really leave. In the years to come, when I hug Delaney or Holly or shake hands with Pat or James or clink beers with Cass, Connie will be there. The part of her that belongs to the earth will be there.

But our atomic selves have that quality of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. We are dust, it’s true, but only until we open our mouths, or share our vulnerabilities, or offer our love. When we laugh. God, what I wouldn’t give to hear Connie cackle one more time, that volcanic joy that shook through you and any room she was in. When those things happen, our souls reveal themselves. That’s when we transcend our elemental building blocks. And when we miss Connie, that’s what we miss. Her soul. Her warmth and wisdom and beauty and laughter and strength and just enough crassness to keep things fun. May we take comfort in each other, and in our memories of this extraordinary woman and the dignity with which she lived every breath. May we be ever thankful for the time we had with her and the richness our lives gained because she was here.

Thank you for loving her. Congratulations on being loved by her. You’ve—we’ve—never been so fortunate.

October 8, 2015

The view from here

So here’s where I cop to a fetish with modern technology: I love the feature on Facebook that allows you to look at your posts from a given day—say, Oct. 8—through the years. It is, usually, a delightful way of reliving moments big and banal and inscrutable. You find out how funny you were. Or how sad and forlorn. You get to slap your forehead and say, “Has it really been (fill in the blank) years since that happened?” The arcs of relationships are right there, at your fingertips. It’s a strange thing to have a digital inventory of artifacts from a dead marriage, for example. Before Facebook, you had to pull out musty photo albums for such experiences.

These days, I’m picking through year-old posts a bit gingerly. It won’t be long before they head to a dark place—the darkest place I’ve ever been, where my circumstance and my involvements with other people came to a horrible confluence. Perhaps I’ll write of it someday. More likely, I’ll do what fiction writers tend to do and plow it into story, where I can find the answers through proxy characters. You know, change the names and the details to protect the innocent and the insignificant.

But here’s the thing about touring old darkness: What I see is not so much the shadows as the coming of the light. It’s a faint, far-off glimmer, imperceptible to me then but part of a larger story now.

I just came back from a whirlwind trip to L.A. with my love, Elisa Lorello. It was, in many ways, the capstone of the season that brought us together and cast us both in a new direction, together. She’s back in New York now, gathering her things. I’m in Montana, preparing for her arrival. We’ll start 2016 together, in the same place, ready to extend our story to new horizons. Gratitude abounds.

It would be cliche to say Elisa pulled me out of the darkness. She didn’t. Rather, with the support of many friends whom I’ll never be able to properly thank—Elisa included—I emerged from that place prepared for what was next. It’s a small distinction, but an important one. I had to get right with myself before I could be right with anyone else.

Lesson learned. More lessons to come. Bring them on.