Craig Lancaster's Blog, page 14

July 6, 2011

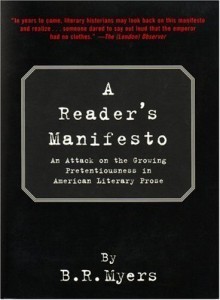

Another Page: 'Bound Like Grass'

One of the more remarkable books I've read in the past few years is this memoir, by Great Falls writer Ruth McLaughlin. In it, she details the story of her family's struggle — ultimately unsuccessful — to survive on homesteaded land in the northeastern corner of Montana.

One of the more remarkable books I've read in the past few years is this memoir, by Great Falls writer Ruth McLaughlin. In it, she details the story of her family's struggle — ultimately unsuccessful — to survive on homesteaded land in the northeastern corner of Montana.

The impressive cover endorsements, from the likes of Mary Clearman Blew and Judy Blunt and William Kittredge, are both on-point and yet somehow lacking (and I say this not to denigrate those who praise McLaughlin's book but rather as an attempt to feebly underscore just how original and striking the book really is).

Clearman Blew: "… Ruth McLaughlin refutes the romantic myths that have distorted our view of the agrarian past."

Blunt: "Her voice is quiet, authentic, and respectful, even as she asks the hard questions and explores the hard truths."

Kittredge: "These lives are absolutely American, and profoundly significant."

All true, undeniably so.

Still, I struggled for a long time to put my finger on what, exactly, so captured me in the pages of McLaughlin's book, and I may still fall short of a full answer. Here's my best attempt: She writes so unblinkingly, without sentiment or equivocation, and yet so evocatively that I was propelled through the pages, knowing in my bones that McLaughlin was offering authenticity and whole-hearted examination of her life and the lives of those who lived alongside her, and yet never once did I see the storyteller's strings. To read this book is to move into every corner of the human heart — not because you're manipulated into doing so, but because that's where McLaughlin's clear-eyed and confidently voiced writing takes you.

Twice, I've heard McLaughlin read from this book — already a Montana Book Award winner — and each time, she chose an early chapter titled "Hunger." There is much to consider there. Here's a taste, where she contrasts her eating habits as a young woman, on her own for the first time, with her memories of the farm:

I ate what I wanted after work and gained weight. I found a store that carried fat red franks, and downed three or four at once. I bought half gallons of ice cream that I spooned from the box, huddled in bed to keep warm; I'd never had more than two scoops at once on top of Jell-O. Trembling from cold, my lips and tongue numb, I stopped just short of finishing the carton.

I could finally have all the ice cream that I wanted, I could turn bright red from franks (my brother maintains that the nitrates from our years of processed meat will keep us pink in our coffins long past death). But neither restored my depleted self as had my grandmother's bath lunch.

Montanans who write memoirs often see their books compared, for good or ill, against Ivan Doig's This House of Sky. A longtime devotee of Doig's, I haven't found much merit in those comparisons. Until now. Ruth McLaughlin's book stands well with that masterpiece, and on its own.

July 5, 2011

Progress Report: 7/5/11

Not a lot to say …

I'm off to Sidney, Montana, this weekend for the Sunrise Festival of the Arts. The last time I was there for the festival, two years ago, I met a ton of nice folks and sold a lot of books. Hoping for more of the same.

I've started a new long-form project. That's all I'm gonna say …

Some very, very good news that I'll be revealing later. I'm such a tease.

Hope you had a wonderful Fourth!

July 4, 2011

Once More, With Feeling: 'The Star-Spangled Banner'

Take it away, Jimi …

Have a happy Fourth, everyone!

July 1, 2011

The Word: Extortionist

The drill: Each week, I ask my Facebook friends to suggest a word. I then put the suggestions into list form, run a random-number generator and choose the corresponding word from the list. That word serves as the inspiration for a story that includes at least one usage of the word in question. This week's contribution is courtesy of Leon Unruh. For previous installments of The Word, click here.

He took a sip off the longneck and handed the bottle to her. She lifted the cold glass to her forehead and held it there a few seconds before taking a gulp of her own.

"Crazy hot," she said.

"Yeah."

They leaned against the hood of his pickup, which sat heavy on its wheels, the back of it filled with the things that he'd held out of the yard sale three days earlier.

"When're you leaving?" she asked.

"Early. Get on down the road. Shut 'er down early."

She handed the bottle back. "No chance you'll stay on a bit?"

"No." He took a swig.

"Don't backwash that thing, mister."

He tilted his head to her, his cheeks bubbled up, holding the beer. She was grinning at him. He swallowed and handed the last of it over to her.

"You've had my spit in your mouth before."

She drained the last of it. "Boy, you are romantic." She leaned toward him, putting her shoulder into his bare right arm. He lifted his arm and she wriggled in, close enough to smell the day's work on him. He wrapped her up, pulled her in tight.

"You want me to stay tonight?" she asked. She pressed her chin against the chambray.

"You want to?"

"I do."

"It's just a sleeping bag on the floor. House is empty."

"I know. It's okay."

"I'm leaving early. Won't get much sleep."

"You already said. I'm not thinking of sleep."

*****

Afterward, she lay her head on his chest and listened as his heartbeat wound down to a normal rhythm.

"I'm gonna miss this," she said.

"We said we weren't talking about that." His words rumbled in his chest, leaving her with an odd sense of stereo – the unadulterated sound entering the ear exposed to the open air, the more guttural, interior version coming through the other.

"We're not. Not really."

"Then what're we talking about?" He sat up a bit, propping himself on his elbows. Rousted from her resting spot, she sat and faced him, the sheet she'd wrapped herself in falling to her waist.

"Nothing. I just …"

"What?"

"I don't know. I guess I didn't believe you were really gonna go back. I mean, I know you said you were, but … well, I just thought you'd decide to stay."

He sat up fully, pulling in his knees. He dropped his head and kept it there awhile. She pulled the sheet back up and draped it over her shoulders, covering her breasts.

"Look," he said, "I never led you on about anything."

"I know."

"I appreciate everything you've done for Mom. I couldn't have managed all of this without you, and this thing, I never expected it …"

"Neither did I."

"But it's done. She's gone. I've closed down the house. It's time for me to go."

"I know."

"So what are we talking about?"

She looked down at the carpet. "I just thought I … You know, when I came back here, I knew I'd never leave. I was hoping you might feel the same way. I thought I could be honest with you, that's all."

"To make me feel guilty?"

"No."

"What, then?"

She looked up at him. "Because you made me feel safe enough to say it. Because I think …"

"What?"

"I think I love you."

"Love? This isn't love."

"It might be for me. You don't know."

"So, what, I'm supposed to say I love you back?"

"No."

"What am I supposed to say, then?" For the first time, there was bark in his words, aggressiveness, anger. It frightened her.

"Whatever you want to say."

"You're an emotional extortionist, you know that? We talked about this. We said it wouldn't be weird."

"It doesn't have to be weird."

"It's already weird!"

She stood and wrapped herself tight in the sheet that smelled like him, like her, like them. "I'm going to go. I'm sorry. I shouldn't have said anything." He reached for her leg, but she backed up out of his reach. "I'm sorry. I'm sorry about your mom. She was a great lady. I'm sorry. I'm really sorry."

She turned and ran for the door in short steps. He watched her go.

*****

He groped in the dark, found the watch and pressed the light button on the side. Two twenty-one a.m. He pushed himself off the spread-out sleeping bag, his back scolding him. He rolled up the makeshift bed and tied it off. He slipped silently into a T-shirt and his jeans, patting the front pockets and finding the outline of his wallet and keys.

In the cab of the pickup, he fired up a Marlboro. He blew a cloud of smoke and watched through the rearview mirror as it diffused.

The engine turned over, and he set the truck in gear. At the bottom of the driveway, he turned right, under a street lamp spraying the asphalt in sullen yellow, and he remembered a night, thirty-odd years earlier, right around this time of year, when he and the girl next door ran circles under that light, catching moths in a Mason jar. He remembered, and he wondered what home would look like tomorrow, when he got back to it.

June 30, 2011

Grab Bag: The Dead Father and the Faux Faulkner Competition

By Jim Thomsen

One recurring feature on my Facebook page is called "What Do You Think Of This Sentence?" I'll then pluck a sentence that caught my eye from whatever I'm reading at a given time—a newspaper, a magazine, a website, a novel, an instruction manual, whatever—and share it with my 800-some Facebook friends. They'll usually snark on it, and usually they're there to be snarked upon.

Craig and I are prolific pouncers-upon of purple prose—mangled metaphors, swirling similes, tiresome tautologies, etc.—that exalts sentence craft over story craft in storytelling. But we probably feel more strongly than most about such things, and usually such Facebook threads get ten to twenty responses before getting lost underneath whatever other crap I've posted on top of it.

Then came last Thursday night, June 23. I posted the following sentence, which came from an anthology of short fiction I've been periodically picking through.

"My father died, and a heavy tether between us was cut, dropping away like a wet rope freed from my waist."

I posted this after ten in the evening, a time when my Facebook traffic usually drops off a cliff, and Craig jumped right on it by suggesting that the sentence should end at cut. He followed with this Onionesque gem.

Publishers Weekly Starred Review. "This spare, parched allegory reveals much about fathers and sons and the many ways in which they go sideways, generation upon generation."

Well, that got me to thinking about how reviewers praise novelist Cormac McCarthy, and inspired me to take a look at "my father died" through McCarthyesque eyes:

"My father died, and I was no longer the son of my father, and I stared and I listened and the horses of my father thundered like echoes of distant cannons across the desert hills, a bloodbeat and blessing and featherbeating and wingwhipping, and the sound of my elegiac grief trailed behind them like the mist of bone and the cry of sinew and the musculature of centurions."

If you're a McCarthy fan and you were offended by that parody, you're welcome.

Craig came right back over the top with a poignant paean to Papa Hemingway:

"My father died. It happened in his study. He built it in 1920. He died in it in 1943. In between, I went to war. Times were hard."

Hemingway is one of Craig's literary heroes. And now that sacred cows were legalized for slaughter, I went straight for the throat of one of my icons, Stephen King:

"My dad did the Buffalo Shuffle off the mortal coil, ayuh, and good fucking riddance to bad trash, that one. I mean, he wasn't that horrible, really, but I didn't need him to show this sonny boy where the bear shit in the buckwheat. And I thought about that as I lit a Lucky Strike in the lovely spill of evening light as it split the coming night down the alley between LeMaire's Luncheonette and an Arby's that had gone tits up sometime during the second Clinton Administration."

And then Craig topped me with a direct slap at the Southern-fried sophistries of Rick Bragg:

"My daddy died, gave up the ghost, kicked the bucket, went to collect his heavenly pension, and danged if anyone knew what we was gonna do then. Momma, of course, carried herself proud. We may have been poor, but we was prideful poor, the only way momma would have it, as she told us that night after giving us a belly full of collard greens."

Having more of a genre bent, my response move was a hack at the world's most successful hack, James Patterson:

"My father died, and my wife was getting ready to go to the funeral with a Juicy Coutoure bag on her arm when a rapist in a ski mask slipped behind her. He placed the sharp metal blade of a knife against the smoothness of her throat and said, "Don't move, bitch, or I'll cut you." Alex Cross burst through the doorway, .38 in hand, and said, "Not this time, Soneji." Cross fired twice and Soneji disappeared in a hail of glass until the next book."

And I followed up with an uninspired swipe at Tom Clancy:

"When my father died, I stood at the helm of an MXPX-3800 manual auxiliary console aboard a CSN&Y 93000 Czologosz-Class U.S. Navy submarine, directing Spy Ops from CenCom through AirSeaSkyDirtSpace Unified Command, my finger near the integrated dual trigger-lock mechanism for twenty-six SSXY 3212 Blaupunkt phelgmtanium-cluster-tipped maxi-nuclear warheads."

And then I just went nuts with this knife-thrust at Dean Koontz:

"My father died and I gazed into pools of blood. My head pounded as strange lights flickered through the darkness of the attic. A premonition came over me: That I was cursed, from this day forward, to make untold millions writing essentially the same book twice a year. And even as my screams rose and caught in my throat, I knew there would be no escape. They would not allow. They. The unseen things in the night. The others. The watchers. The bringers. The HVAC installers. All ran together in my fevered dreams like rivers of cold, twisted hate …."

Actually, I think that one pretty much was dead-on. Craig weighed in again with a masterly stab at the eminently stabbable William Faulkner:

"My father did not feel weak, but he died just the same, luxuriating in the vicissitudes of the flesh, that supremely souciant state of being in which love, honor, cherish neither exist nor erode — the accumulations of the seconds and hours and epochs to which a body, any body and all bodies, must hew to the demands of the earth and the heavens, no longer supplicant but instead mendicant to the vagaries of time's rapprochement."

And I tossed a rhetorical harpoon at Herman Melville:

"O! My father has passed! Come ye, Starbuck and Stubb, tarry not in yer sorrow. Damn you, but he is God's true prince from the empire of the world's hustings, and I am game for his crooked jaw, as I am for the whale that vexes me from the Cape Of Mediocre Hope to the apogee of the Orkneys. He pleaseth me in his countenance and in his form, and I shall make him spout black blood until he rolls fin out, much as I shall roll Ishamel's darling half-breed in the naked slumber of his beth belowdecks. O Queequeg! He shall be laid with iron rails, whereon my soul is grooved to run. Over unsounded gorges, through the rifled hearts of mountains, under torrents' beds, unerringly I boff! Naught's an obstacle, naught's an angle to the iron way! Or something."

Craig then took an affectionate poke at Larry McMurtry:

"My father died halfway between Dodge City and Ogalalla, a damn sight away from any town that was worth a piss on the prairie. Fortunately, the problem of where to plant him was solved one afternoon when we ran into a party of buffalo soldiers with a mule team who had relieved the tedium of travel by getting drunk. They were generous men, and they took my father's body and considerately let it ride in the wagon."

Then we took our first request from a mutual friend following the exchange, and Craig accepted the challenge of Mock John Irving:

"My father detested many things, but what he detested most was dying; this struck most of us as a curiosity, as Herman Bellblather hadn't died before, as he was, right up to the moment he did perish, quite alive. Nevertheless, my father considered dying the sort of endeavor that required more time and effort — endless amounts of both — than he found himself willing to expend. It was this belief in the superfluous nature of death that kept him from buying a proper coffee pot for the entirety of his life, something he surely must have considered as the heart attack took him away for good."

I didn't have much parodic gas left in the tank, but burned what vapors I had on Don DeLillo:

"My father died. And all I could think to do was go shopping. So I went to the Price Garroter down the street and filled my geometrically pleasing shopping cart with franks and beans and greens and creamed corn and corn oil and motor oil and soy milk even though I didn't drink soy milk and tortillas and ranch dip and Tide With Extra White Brighteners and Waffle Crisp and Quaker Instant Oatmeal Because It's The Right Thing To Do and Stay Free Panti-Liners With Wings That Draw Away Wetness and Hefeweizen Apricot Asparagus Abalone Winter Summer Wheat Berry Hop Beer because if I'm happy and I know it I should clap my hands right and I crawled into the child seat of the cart and cried and cursed the obscure absurd postmodern comic irony of it all, inaccessible only to me and to The New York Times Book Review and the judges of the National Book Award, and my father was still dead."

Craig then closed out the manic run with a sendup of that dirty old bastard Philip Roth:

"During the war years, in Newark, my father died. His was a magical name on our street, even to those whose blood ran back to the Prince Street ghetto days. Upon his passing, he bequeathed to me a watch of intricate parts and inimitable reliability, a watch constructed by Sol Schwarzheim, who was known in Newark for two things. The rugged beauty of his timepieces and his penchant for swimming at the shore."

Brilliant. And yet, so many writers, so ripe for parody, have been left unpunctured here. I mean, no Raymond Carver? No John Steinbeck? Elizabeth Gilbert? Charles Bukowski? Jhumpa Lahiri? (Okay, I've never read Lahiri, but if The New York Times Review Of Books loves her so much, there must be something there to make fun of.)

So, never having been ones to voluntarily shut off the snark valve, Craig and I will open the floor.

One, give us the name of an author you'd like to see us parody. One of us will take it on.

Or two, feel free to add your own author parody here.

(We should also hasten to point out that we love authors. Love them. We are them. This isn't about swamping anybody's boat; it's about celebrating the other side of the truism that there is magic in words—in this case, the magic being that nobody is too big and important for some good, clean fun.)

June 29, 2011

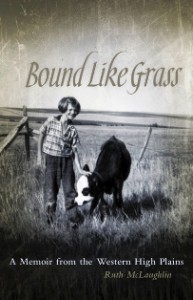

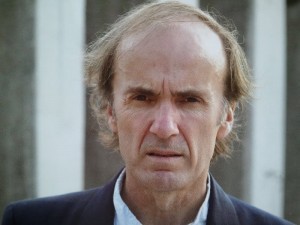

Another Page: 'A Reader's Manifesto'

This book is what I've been reading for the past few days. It's not a new book; just new to me. And it entered my view at a time when I've really been struggling with some of the things I read, things that have received near-universal acclaim but leave me cold, never allowing me to slip out of my own world and into the realm of the characters on the page because the prose is so stultifyingly self-conscious. As I tend to come from a Potter Stewart-like sensibility about the merits of literature — I know what I like when I see it — I thought that B.R. Myers' book might coagulate some of the thoughts I've been entertaining.

Did it succeed? Well, it sounds like a copout, and maybe it is, but yes and no.

Oh, where to begin:

First, the book is not at all falsely billed. If you use a word like manifesto in your title, you better come packing stridency and a take-no-prisoners approach to your topic. B.R. Myers certainly does. With a subtitle of "An Attack on the Growing Pretentiousness in American Literary Prose," Myers' words live up to his stated objective. It's definitely an attack, and there's definitely pretentiousness in some quarters of literary prose in this country.

Second, the very things that validate the title — the relentless takedown of some of America's best known and most highly regarded literary writers, the gleeful pounding of preeningly precious prose — are the things that give a more moderate reader pause. At several junctures, Myers attempts to crawl a bit too deeply into these writers' heads, ascribing to them an intentionally deceptive approach to writing that sends things a bit too deep into conspiracy-theory land for my taste.

A good example of this is Myers' examination of this selection from the E. Annie Proulx novel Accordion Crimes:

She stood there, amazed, rooted, seeing the grain of the wood of the barn clapboards, paint jawed away by sleet and driven sand, the unconcerned swallows darting and reappearing with insects clasped in their beaks looking like mustaches, the wind-ripped sky, the blank windows of the house, the old glass casting blue swirled reflections at her, the fountains of blood leaping from her stumped arms, even, in the first moment, hearing the wet thuds of her forearms against the barn and the bright sound of the metal striking.

Myers writes: "The last thing Proulx wants is for you to start wondering whether someone with blood spurting from severed arms is going to stand 'rooted' long enough to see more than one bird disappear, catch an insect, and reappear, or whether the whole scene is not in bad taste of the juvenile variety."

That's a step too far for me. I'm happy to talk about the merits of the sentence, and Myers' criticisms strike me as sound and reasonable, but I'm simply not willing to say what Proulx does or does not want from me or that she was quite deliberately trying to draw my attention away from the questions Myers poses. And that's the thing: Myers does this continually in the book, with each of the writers he goes after.

The book focuses its takedowns on five authors: Proulx (oh, how Myers delights in tearing into her, even holding up a book's dedication to withering criticism), Don DeLillo, Cormac McCarthy, Paul Auster and David Guterson, dropping them, respectively, into categories of "evocative," "edgy," "muscular," "spare" and "generic literary." The first four, you might well note, are some of the most common adjectives in reviews of literary work.

Where Myers succeeds most thoroughly is in the sheer number of pretentious passages he unearths, demonstrating convincingly that the perception of deep literary value is often nothing more than a trick of the light, a way of arranging the words to achieve a tonal effect that, when deconstructed, reveals little.

Here's one from McCarthy, a snippet that employs the "andelope," a word made up by Myers that denotes "a breathless string of simple declarative statements linked by the conjunction and":

He ate the last of the eggs and wiped the plate with the tortilla and ate the tortilla and drank the last of the coffee and wiped his mouth and looked up and thanked her.

Myers writes: "… the unpunctuated flow of words bears no relation to the methodical meal that is being described. Not for nothing do thriller writers save this kind of breathless syntax for climactic scenes of violence. … And why does McCarthy repeat tortilla? When Hemingway writes, 'small birds blew in the wind and the wind turned their feathers' ('In Another Country,' 1927) he is, as David Lodge points out, using wind in two different senses, and creating two sharp images in the simplest way possible."

That's good stuff.

The book teems with examples like that, with level-headed, sensible explanations of why such affectations often are pointless. And Myers certainly is correct when he says that such pretentiousness is multiplying as newer writers, who genuflect at these altars, commit similarly errant prose in their own work. The evidence is out there, on bookstore shelves, for anyone who cares to look for it.

Here again, though, I end up feeling a bit hinky about endorsing Myers' findings to the point of zealotry. I'm reminded of conversations with friends — some of which I've detailed previously — who like this kind of writing. I don't think they like it because they've been brainwashed or they're unable to see the merits in more workmanlike prose. They simply like what they like, and in the end, isn't this true of all of us? (That brings to mind another conversation I had a couple of years ago with a high school friend, who was arguing vociferously for the objective standard of good art, while I was taking, as I'm wont to do, the more populist approach. He got a bit angry with me, and I responded with this: "You're just pissed off because I refuse to tell Britney Spears fans that they're wrong." That seemed to lighten the mood, if not settle the dispute.)

In the latter part of the book, Myers deals directly with critics of the original Atlantic article that became the basis of the book. He defends himself well — and rather seems to enjoy it, so much so that I'm a little worried he'll find this piece and tell me that I'm a two-bit hack clown. Luckily, I've been called worse.

Finally, he wraps up with "Ten Rules for 'Serious' Writers." For me, this was the most disappointing part of the book, juvenile and predictable. Here's a taste:

I. Be Writerly: Read aloud what you have written. If it sounds clear and natural, strike it out. This is the whole of the law; the rest is gloss.

Coming at the end of a long, fascinating piece as they do, these rules smack of taunting and repetition. I really wish Myers had left them out; if any reader comes across them ripe to be swayed, he will more likely be turned off.

In total, though, it's a worthwhile, illuminating read. Myers brings out the long knives and carves up a lot of writing, and regardless of where you stand, his points are so learned and well-argued that it's worth considering what he has to say. I came away from the book with a clearer mind about what I've been reading lately but also with the motivation to better acquaint myself with the work of those authors Myers attempts to slaughter. A good example: I've not read Paul Auster, and I found myself enjoying many of the selections of his that Myers was holding up to ridicule. I also remembered, even as I guffawed at some of the McCarthy criticism, that I found No Country For Old Men and The Road — the only two McCarthy titles I've read — artful and moving. Same with Proulx, who for whatever flaws Myers might have exposed has written some breathtaking stories.

In other words, I emerged from the pages of Myers' book with respect for its message and with my own sensibility, however flawed, still intact.

June 28, 2011

Progress Report: 6/28/11

Confession time: I have nothing to report.

The short-story collection that has taken up the bulk of my time for the past year is finished and delivered to my editor.

Ed Kemmick's book is mostly out the door.

I've done a couple of library gigs — Ronan (Montana) on June 16th and Columbus (Montana) a week later.

Next week begins my summer festival season:

July 9: Sunrise Festival of the Arts in Sidney, Montana.

July 23: Joliet Jamboree in Joliet, Montana.

August 6: Madison Valley Arts Festival in Ennis, Montana.

August 20: Manhattan Potato Festival in Manhattan, Montana.

Until tomorrow …

June 27, 2011

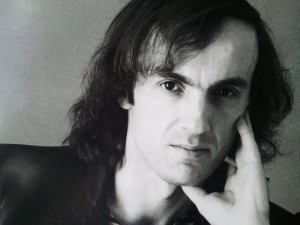

Once More, With Feeling: An Interview With Paul Roberts of Sniff 'n' The Tears

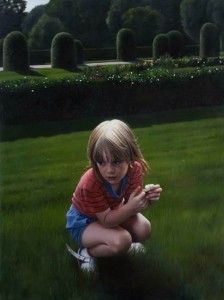

Paul Roberts, 1978

By Jim Thomsen

Last week, I rhapsodized about one of my favorite pop-rock bands, Sniff 'n' The Tears. But I was really giving mad props to just one person: Paul Roberts, the band's founder, singer, songwriter and sole constant since the British group came together in 1977. I've always been a fan of auteur types, artists who take control their own universe—sometimes by force—and make their art better for keeping it as undiluted as possible. I also admire artists who work for the sake of the art—and the craft—and aren't obsessed with stardom. (When Roberts got burned out on music from time to time—he's recorded one album per decade since the early Nineties—he turns to his second artistic career as a gallery-quality painter who created the Sniff album covers.) Roberts qualifies on all scores.

And so it was a pleasure to find that the Somerset, Great Britain, resident—now sixty-two and a father of three grown daughters—was willing to answer some questions via e-mail for our benefit.

Enjoy a visit with the man who brought the insanely catchy "Driver's Seat" into the world. (And I should hasten to add that the new Sniff album, Downstream, which was released just this spring, is an accessible, absolutely wonderful collection of grown-up pop-rock gems. If you need a touchstone, I can safely say that if you like Dire Straits and Mark Knopfler's solo recordings, you'll find much to relate to and admire in this self-produced, self-released, under-the-radar delight.)

Q: Why a new album, after eleven years away ? Do you, in your sixties, feel any particular urge to round up a group of friends and hit the road?

A: I make the records because I love doing it, I don't have unrealistic expectations for them but there are enough "Sniff" fans to make it worthwhile. As for touring, I would love to, but the demand would have to be there for promoters etc to get behind it.

Q: How often did you tour America with the band, and what are your memories of those days? Who did you open for, and were you received and treated well? Or were there some memorable bad times? Did touring tend to bring the band together or expose the personal differences among members?

A: We did one two-and-a-half-month-long American tour in 1979. The first half of the tour we supported Kenny Loggins and the other half, Kansas. On that tour only (guitarists) Loz Netto and Mick Dyche remained from the original band; Chris Birkin and Alan Fealdman had left. Chris had his own band and didn't want to commit to Sniff now that success beckoned and Alan literally did not want to give up his day job which I believe he still has. Drummer Luigi Salvoni did not want to do the tour and was opposed to our new manager, Bud Prager, (who was instrumental in Foreigner's success), who he felt was steering the band in the wrong direction.

In retrospect, I think he was right, but … we had a great time on tour and everybody got along fine, but in hindsight it would have been far better to have done a club tour. Bud felt we'd reach more people playing coliseums with Kansas but that goes back to the generic pop fodder argument. Now I think it's better to play to an audience, however small, that is in to you.

Q: In listening to the Downstream lyrics, your thematic concerns seem to be more about the outside world — sometimes in torn-from-the-newspaper way, and sometimes in an appreciating-the-wonder-of-the natural-world way. Whereas in the first four Sniff albums, your concerns seemed proportionately more about the worlds between men and women. What does that say about the Paul Roberts of, say, 1978, as opposed to the Paul Roberts of today?

A: When you're young, relationships are what occupy your mind, everything else is secondary. When the turmoil of raging hormones is behind you, you worry about what kind of world your children have to deal with. A more reflective state of mind.

"Buttoning The Red Dress," an oil-on-canvas painting by Paul Roberts

Q: Why do you think Sniff 'n' the Tears didn't sustain the commercial success portended by the breakthrough of "Driver's Seat"? Was it about how the music didn't fit into the music of the moment between 1978 and 1982? Was it about band stability? About label promotion and distribution? About your experiences on the road? Or was it about what was going on with you on a personal level?

A: I have never contemplated making music which "fitted in" with the times. I try and do what comes naturally, and work with musicians who complement that. In the music business, there are a lot of things that can go wrong and I would say it takes a huge amount of focus and determination to circumnavigate the pitfalls. We were unlucky in a number of areas and maybe not determined enough in others.

Q: After four albums in five years, you were without a record contract at the end of 1982. At that point, what were your thoughts about what to do with the rest of your life? Did you want music as much as painting, still, as viable careers? Or did you maybe think about packing it all in, in your mid-thirties then, and go somewhere completely different and do something completely different?

A: Chiswick were a small independent label who had done well out of licensing the band worldwide but they were not equipped to promote us properly themselves. So by the time we got to "Ride Blue Divide", the last contracted album, believe me, there was no desire to continue working with them. I'd say that Love/Action (the band's third album, released in 1981) was the one that should have changed our fortunes but we had been coerced into using a "producer" which Bud Prager felt had been lacking on the first two albums and going for a more produced sound. I don't think it worked. It's the album which to me sound most dated. It was time to take a raincheck, and that's what we did.

Q: How would you describe yourself as a bandmate vs. a bandleader?

A: My main reason for wanting a band was for that interaction and consistency but I also I wanted my songs to be central to the concept.

"The Holly Walk," an oil-on-canvas painting by Paul Roberts (2007)

Q: My theory about why Sniff 'n' the Tears wasn't a bigger radio/commercial sensation is this: The songs, like your singing voice, seems to exist in a middle register of emotion, lacking the anthemic soaring or the pumped-up dance-floor urgency of the biggest hits of the time. Your music, like your voice, doesn't wail or rip or shred. They're songs that simply lope along in second or third gear with great shimmery competence, complementing the comparative dryness of your vocal style, but they don't grab listeners by the throat in the way that, say, The Clash did. Or Journey. Or just about anybody who was "big" then on the radio.

A: You mention The Clash and Journey; I remember two of the biggest bands at the time were The Eagles and Fleetwood Mac, not to mention Tom Petty. One of my favourite bands ever would be Little Feat, who as far as I know never had a hit. Music is a broad church; I wasn't plotting how to storm the charts, I just wanted to do music that I could feel proud of in my own way. Dire Straits had a second album failure but came back with a strong third album. In my opinion, that's what we failed to do.

Q: It certainly wasn't a function of the catchiness of the songs, or their arrangements or musicianship, in my opinion, because deep album cuts like "Roll The Weight Away" or "The Game's Up" or "Steal My Heart" or "The Thrill Of It All" or "5 & Zero" float unbidden into my forebrain as often, if not more, than "Driver's Seat" … but they do so in a sneak-up-on-me sort of way. I see them as subtle delights, rather than overt ones. What do you think?

A: The industry in those days was, and probably still is, geared for mega-success. A lot of the music I love is not that obvious, but there is room for it. Bud Prager, our manager, at the time also managed Foreigner. (He) believed that unless you made music that appealed to teenage boys in the Midwest, you could never hope to sell twelve million albums … which he seemed to think was the point. I never thought that was the point. I hoped that if I made good enough music that there would be enough people out there to build a sustainable career. For me, Tom Petty has done that. So has Paul Simon, JJ Cale, Tom Waits and many others. If something grows on you, it will stay with you for longer.

Q: I remember you saying not too long ago in an interview that Sniff 'n' the Tears suffered early on in the public consciousness by being compared to Dire Straits and the London pub-rock scene. But Downstream has many songs that sound … well … Knopfleresque. (The opening guitar licks on "Black Money," for instance, sound like Mark Knopfler was sitting in on the recording session.) Have you grown more at ease with those parallels, however unfair they might have seemed at the time, given that your second, third and fourth albums went in move of a New Wave direction that Dire Straits never touched?

A: What had happened was that we had in fact recorded Fickle Heart (Sniff's first album, recorded in 1977 and released in 1978) before Dire Straits' first album. In fact, me and (guitarist) Mick Dyche ran into (original Dire Straits drummer) Pick Withers and were discussing this with him in Wardour Street when we were mastering and they were still recording. Unfortunately Chiswick's distributor then went bankrupt and they didn't finalise their deal with EMI for another year, so we found ourselves being accused of following in the path of Dire Straits. (As they say in the movies, any similarity is purely coincidental.) I never really thought the comparison bore too much scrutiny, but we were both laid-back muso-ish bands in the days of the three-chord thrash. New Wave was a meaningless description even then. All it described were the bands that had more to offer than attitude and haircuts.

Q: What have you been doing, for the most part, since the late 1980s, after your pair of solo albums? You seemed to take yourself off the regular-recording path. Has it been all painting, or have you been doing other work? Concentrating on your family? Traveling? Finding other artistic pursuits?

A: We made an album, No Damage Done, in 1992 and then toured Germany and Benelux. (Jim's note: I actually overlooked this album since Allmusic.com doesn't list it in its database, nor did I see it on Sniff's Amazon page. Apparently, it was an import-only album. I'm glad Paul alerted me to it, for it was like Christmas for me—a "new" Sniff album to enjoy!) I might re-release it as I think I probably now own the rights. I have, of course, also been painting and enjoying seeing my children grow up.

Q: How would you describe your relationship with "Driver's Seat"? A lot of artists tagged as "one-hit wonders"—and, sadly, that's how America probably sees you since I believe that it's the only song that got real airplay here—tend to resent being defined by the one song that gets cemented to their names. They tend to say, "You know, I wrote and recorded a lot of other good songs, too, you know. Hello?"

A: I've always felt that if you had to be a one-hit wonder, then "Driver's Seat" was a pretty good song to be remembered by. People still love it. It's not cheap or cheesy or formulaic. It's got a great energy. Of course, there are other songs I'm proud of, but what the hell. I would never not play "Driver's Seat."

Q: If somebody wrote a book about your life, or if you wrote a memoir, what do you think it should be called?

A: What Next?

Paul Roberts, 2011

Jim Thomsen is a freelance writer and manuscript copyeditor who lives near Seattle. His clients have included well-known crime authors Gregg Olsen, M. William Phelps and J.D. Rhoades. He is at work on The Last Ferry of the Night, a literary crime novel, among other projects, but he could always use more work to pay the bills. Reach him at thomsen1965@gmail.com.

June 24, 2011

The Word: Phlegmatic

The drill: Each week, I ask my Facebook friends to suggest a word. I then put the suggestions into list form, run a random-number generator and choose the corresponding word from the list. That word serves as the inspiration for a story that includes at least one usage of the word in question. This week's contribution is courtesy of Kathy Price (the second word she's chosen!). For previous installments of The Word, click here.

Eddie Dorsett was a dumb kid. Nobody could dispute it. More than that, Eddie Dorsett was a fat, slothful, whining, shilly-shallying, phlegmatic zero of a kid, the lowest of the third-graders for certain and a prime contender for the lowest of the entire Rutherford Hodges Elementary student population, no small dishonor. In the fall of seventy-eight, you could argue, Hodges Elementary was overrun by layabouts, hoods in training, crumb factories, carpet rats and crackers, and Eddie Dorsett, the sniveling little shit, was one of them. Maybe the worst of them.

So it was not without reservation that I stepped between Eddie and Mike Brill that October before Brill could blacken Eddie's other eye.

"Leave him alone."

Brill, the tallest kid in our class but one whose constitution wouldn't allow him to take on anyone but the weakest kids, stopped his advance on Eddie. "What's it to you?" he said. His cohorts – wingmen, I guess you'd call them today – looked at Brill and each other, uncertain what to do. I'd counted on that. If the three of them had been capable of rubbing together two cogent thoughts, they easily could have given me the ass-kicking they intended for Eddie.

"Just leave him alone, Mike," I said. "He hasn't done anything to you."

Brill stepped backward, something else I'd counted on, as he tried to save face. "It must be save-a-dork week. Or join-a-dork week. You joining up with the dorks, Rodney?" His slope-headed sycophants laughed and slapped Brill on the back, even as they walked backward with him.

I didn't say anything to that. I just kept my fists clenched, all the message the likes of Mike Brill needed. He threw a couple more sneers at me for good measure, and soon enough, he was on the other side of the recess yard, tormenting Roger Prager, who probably deserved it.

I turned to Eddie, still on the ground where he'd fallen into a defensive posture like the pill bugs I'd spent much of the summer crushing between my fingers.

"Get up," I said. "He's gone."

Eddie flopped onto his back, sat up and then scrambled to his feet, looking for all the world like a miniature version of Boss Hogg in Tuffskins.

"Thanks for that," he said. "Nobody ever stuck up for me before."

I didn't even look at him as I walked away. "Don't mention it."

*****

The fat little fucker mentioned it. Somebody did, anyway. Mrs. Dorsett came by the house that night with Eddie in tow. (Mr. Dorsett — whose existence could be divined by the malformed mound of genetic material standing in our living room but who'd never been seen by me or anyone I knew — was out of town, his wife said.) She had these enormous pillows of fat hanging from her upper arms, and they became cellulitic metronomes, moving in time as she swung those fleshy stubs of hers around, excitedly telling my folks what I'd done for her boy.

Mom stood next to me and patted me on the head as Mrs. Dorsett unspooled the account of the thing. She got key details wrong, most notably that Eddie was backed into a corner rather than cowering in the dirt.

"Did you hit that boy, Rodney? Did you give him what for?" Dad asked.

"No."

"Too bad. Sometimes with a boy like that, a punch in the nose is the only thing that will get through."

I looked at Mrs. Dorsett and she was nodding, and it was only by the grace of my upbringing that I didn't ask her why she was nodding at me when she should have been stuffing that good advice into the ears of her idiot son.

"Well, I'm just so sorry about what those awful boys are doing to Eddie," Mom said, reaching out and patting Mrs. Dorsett's doughy arm.

I looked at Eddie and he had half a finger jammed into his nostril.

*****

The next morning, Mom laid it out for me.

"The Dorsett boy is going to start spending the night over here a few nights a week."

I spat out my toast. "What? Why?"

"That family is in a bad way, and we can help. His mom got an offer to work the night shift at the hospital, and Eddie's dad is gone a lot, so he's going to stay here."

I looked at Dad. He tugged the sports page higher, covering his face.

"Why us? Doesn't she have family?"

"I'll tell you why, young man. First, no, she doesn't have family here in town. Second, we do not turn our back on neighbors in need. And third, you're friends with the boy. You can help him."

"I'm friends with him?" I looked again at Dad. He shook the paper but made no signal that he'd be joining the conversation. "I'm not friends with that freak."

"Rodney!"

"Well, I'm not. I can't believe you're doing this." I shoved back from the table and slipped behind Dad, breaking into a full-on sprint for my bedroom.

*****

That night, I lay in bed, staring into the gray darkness at the bunk above me, now occupied by the smelliest kid I knew. Holy hell, it was bad, like the stench of my father's loafers and full diaper battling it out for airspace.

"Rodney?"

"What?"

"Will you be my best friend?"

I closed my eyes and bit my upper lip.

"Well, will you?"

I opened them. "How many friends you got?"

"Well … I guess, just you, pretty much."

"Well, Eddie," I said, with the resignation of a condemned eight-year-old, "I guess that makes me your best friend." The mattress above me, protuberant from Eddie's ample ass, jiggled happily.

"Thanks, Rodney."

"Don't mention it."

"Rodney?"

"Look, Eddie, let's just go to sleep, okay?"

"Okay." He shifted in bed and the mattress morphed above me.

"Rodney?"

"What?"

"You're not mad at me, are you?"

"No. Go to sleep."

"Okay."

I waited, eyes open. Ten minutes. Fifteen. Twenty.

Finally, blessedly, came the sound of slumber. Naturally, Eddie snored, but under the circumstances, I was more than willing to accept that.

"No, I'm not mad at you," I whispered into the darkness. "I just think you're a P-U-S-S-Y."

June 23, 2011

Grab Bag: Notes on a Poem

I really don't want to make a huge deal about my poem, Eastward Ho, that was recently published by The Montucky Review. I certainly never expected to publish a poem; I know how bad most of my attempts at the form truly are. But now that an editor has seen something in the work, my wife, Angie, suggested that I give a little background on it.

So here goes …

I spent my first summer in Montana drinking beer and making stupid faces. Pretty much how I've spent every summer since.

I wrote it in the early fall of 2006, just months after I'd moved to Montana from California to start my life here with Ang. I'd made the trip here that June with a bit of money in the bank, and I figured I could float along for the better part of a year, if I had to, without finding full-time work. As it turned out, I was in town less than a month before something opened up at The Billings Gazette, and so I was back on the job fairly quickly.

The poem, whether it's obvious or not, was the result of some conflicting feelings I had about my situation — personal and professional. Between the time I started my career in earnest in the early '90s and the time I came to Montana, I'd been married to my work — pouring my energy and my passion into journalism. When I came to Montana, that changed. I still enjoy working with words and designing pages and the thrill of a big breaking story, and I still hold myself to a high standard of work, but my arrival here was driven, at least in part, by the sudden realization, at age 36, that work would never love me back. And I now had someone in my life whom I'd never let in before, someone who would love me back.

That was the dynamic at work as I wrote the poem, the letting go of a job as the most important thing in my life and the embracing of another human being in that role. Marriage has not been easy, mostly because I'm not an easy person, but this I can say with all conviction: I've never regretted the trade.