Once More, With Feeling: An Interview With Paul Roberts of Sniff 'n' The Tears

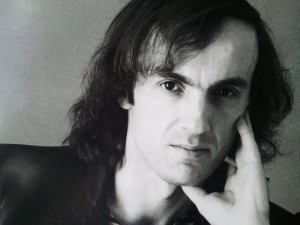

Paul Roberts, 1978

By Jim Thomsen

Last week, I rhapsodized about one of my favorite pop-rock bands, Sniff 'n' The Tears. But I was really giving mad props to just one person: Paul Roberts, the band's founder, singer, songwriter and sole constant since the British group came together in 1977. I've always been a fan of auteur types, artists who take control their own universe—sometimes by force—and make their art better for keeping it as undiluted as possible. I also admire artists who work for the sake of the art—and the craft—and aren't obsessed with stardom. (When Roberts got burned out on music from time to time—he's recorded one album per decade since the early Nineties—he turns to his second artistic career as a gallery-quality painter who created the Sniff album covers.) Roberts qualifies on all scores.

And so it was a pleasure to find that the Somerset, Great Britain, resident—now sixty-two and a father of three grown daughters—was willing to answer some questions via e-mail for our benefit.

Enjoy a visit with the man who brought the insanely catchy "Driver's Seat" into the world. (And I should hasten to add that the new Sniff album, Downstream, which was released just this spring, is an accessible, absolutely wonderful collection of grown-up pop-rock gems. If you need a touchstone, I can safely say that if you like Dire Straits and Mark Knopfler's solo recordings, you'll find much to relate to and admire in this self-produced, self-released, under-the-radar delight.)

Q: Why a new album, after eleven years away ? Do you, in your sixties, feel any particular urge to round up a group of friends and hit the road?

A: I make the records because I love doing it, I don't have unrealistic expectations for them but there are enough "Sniff" fans to make it worthwhile. As for touring, I would love to, but the demand would have to be there for promoters etc to get behind it.

Q: How often did you tour America with the band, and what are your memories of those days? Who did you open for, and were you received and treated well? Or were there some memorable bad times? Did touring tend to bring the band together or expose the personal differences among members?

A: We did one two-and-a-half-month-long American tour in 1979. The first half of the tour we supported Kenny Loggins and the other half, Kansas. On that tour only (guitarists) Loz Netto and Mick Dyche remained from the original band; Chris Birkin and Alan Fealdman had left. Chris had his own band and didn't want to commit to Sniff now that success beckoned and Alan literally did not want to give up his day job which I believe he still has. Drummer Luigi Salvoni did not want to do the tour and was opposed to our new manager, Bud Prager, (who was instrumental in Foreigner's success), who he felt was steering the band in the wrong direction.

In retrospect, I think he was right, but … we had a great time on tour and everybody got along fine, but in hindsight it would have been far better to have done a club tour. Bud felt we'd reach more people playing coliseums with Kansas but that goes back to the generic pop fodder argument. Now I think it's better to play to an audience, however small, that is in to you.

Q: In listening to the Downstream lyrics, your thematic concerns seem to be more about the outside world — sometimes in torn-from-the-newspaper way, and sometimes in an appreciating-the-wonder-of-the natural-world way. Whereas in the first four Sniff albums, your concerns seemed proportionately more about the worlds between men and women. What does that say about the Paul Roberts of, say, 1978, as opposed to the Paul Roberts of today?

A: When you're young, relationships are what occupy your mind, everything else is secondary. When the turmoil of raging hormones is behind you, you worry about what kind of world your children have to deal with. A more reflective state of mind.

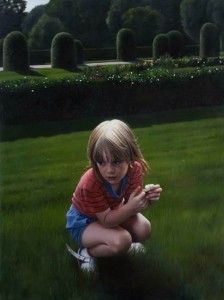

"Buttoning The Red Dress," an oil-on-canvas painting by Paul Roberts

Q: Why do you think Sniff 'n' the Tears didn't sustain the commercial success portended by the breakthrough of "Driver's Seat"? Was it about how the music didn't fit into the music of the moment between 1978 and 1982? Was it about band stability? About label promotion and distribution? About your experiences on the road? Or was it about what was going on with you on a personal level?

A: I have never contemplated making music which "fitted in" with the times. I try and do what comes naturally, and work with musicians who complement that. In the music business, there are a lot of things that can go wrong and I would say it takes a huge amount of focus and determination to circumnavigate the pitfalls. We were unlucky in a number of areas and maybe not determined enough in others.

Q: After four albums in five years, you were without a record contract at the end of 1982. At that point, what were your thoughts about what to do with the rest of your life? Did you want music as much as painting, still, as viable careers? Or did you maybe think about packing it all in, in your mid-thirties then, and go somewhere completely different and do something completely different?

A: Chiswick were a small independent label who had done well out of licensing the band worldwide but they were not equipped to promote us properly themselves. So by the time we got to "Ride Blue Divide", the last contracted album, believe me, there was no desire to continue working with them. I'd say that Love/Action (the band's third album, released in 1981) was the one that should have changed our fortunes but we had been coerced into using a "producer" which Bud Prager felt had been lacking on the first two albums and going for a more produced sound. I don't think it worked. It's the album which to me sound most dated. It was time to take a raincheck, and that's what we did.

Q: How would you describe yourself as a bandmate vs. a bandleader?

A: My main reason for wanting a band was for that interaction and consistency but I also I wanted my songs to be central to the concept.

"The Holly Walk," an oil-on-canvas painting by Paul Roberts (2007)

Q: My theory about why Sniff 'n' the Tears wasn't a bigger radio/commercial sensation is this: The songs, like your singing voice, seems to exist in a middle register of emotion, lacking the anthemic soaring or the pumped-up dance-floor urgency of the biggest hits of the time. Your music, like your voice, doesn't wail or rip or shred. They're songs that simply lope along in second or third gear with great shimmery competence, complementing the comparative dryness of your vocal style, but they don't grab listeners by the throat in the way that, say, The Clash did. Or Journey. Or just about anybody who was "big" then on the radio.

A: You mention The Clash and Journey; I remember two of the biggest bands at the time were The Eagles and Fleetwood Mac, not to mention Tom Petty. One of my favourite bands ever would be Little Feat, who as far as I know never had a hit. Music is a broad church; I wasn't plotting how to storm the charts, I just wanted to do music that I could feel proud of in my own way. Dire Straits had a second album failure but came back with a strong third album. In my opinion, that's what we failed to do.

Q: It certainly wasn't a function of the catchiness of the songs, or their arrangements or musicianship, in my opinion, because deep album cuts like "Roll The Weight Away" or "The Game's Up" or "Steal My Heart" or "The Thrill Of It All" or "5 & Zero" float unbidden into my forebrain as often, if not more, than "Driver's Seat" … but they do so in a sneak-up-on-me sort of way. I see them as subtle delights, rather than overt ones. What do you think?

A: The industry in those days was, and probably still is, geared for mega-success. A lot of the music I love is not that obvious, but there is room for it. Bud Prager, our manager, at the time also managed Foreigner. (He) believed that unless you made music that appealed to teenage boys in the Midwest, you could never hope to sell twelve million albums … which he seemed to think was the point. I never thought that was the point. I hoped that if I made good enough music that there would be enough people out there to build a sustainable career. For me, Tom Petty has done that. So has Paul Simon, JJ Cale, Tom Waits and many others. If something grows on you, it will stay with you for longer.

Q: I remember you saying not too long ago in an interview that Sniff 'n' the Tears suffered early on in the public consciousness by being compared to Dire Straits and the London pub-rock scene. But Downstream has many songs that sound … well … Knopfleresque. (The opening guitar licks on "Black Money," for instance, sound like Mark Knopfler was sitting in on the recording session.) Have you grown more at ease with those parallels, however unfair they might have seemed at the time, given that your second, third and fourth albums went in move of a New Wave direction that Dire Straits never touched?

A: What had happened was that we had in fact recorded Fickle Heart (Sniff's first album, recorded in 1977 and released in 1978) before Dire Straits' first album. In fact, me and (guitarist) Mick Dyche ran into (original Dire Straits drummer) Pick Withers and were discussing this with him in Wardour Street when we were mastering and they were still recording. Unfortunately Chiswick's distributor then went bankrupt and they didn't finalise their deal with EMI for another year, so we found ourselves being accused of following in the path of Dire Straits. (As they say in the movies, any similarity is purely coincidental.) I never really thought the comparison bore too much scrutiny, but we were both laid-back muso-ish bands in the days of the three-chord thrash. New Wave was a meaningless description even then. All it described were the bands that had more to offer than attitude and haircuts.

Q: What have you been doing, for the most part, since the late 1980s, after your pair of solo albums? You seemed to take yourself off the regular-recording path. Has it been all painting, or have you been doing other work? Concentrating on your family? Traveling? Finding other artistic pursuits?

A: We made an album, No Damage Done, in 1992 and then toured Germany and Benelux. (Jim's note: I actually overlooked this album since Allmusic.com doesn't list it in its database, nor did I see it on Sniff's Amazon page. Apparently, it was an import-only album. I'm glad Paul alerted me to it, for it was like Christmas for me—a "new" Sniff album to enjoy!) I might re-release it as I think I probably now own the rights. I have, of course, also been painting and enjoying seeing my children grow up.

Q: How would you describe your relationship with "Driver's Seat"? A lot of artists tagged as "one-hit wonders"—and, sadly, that's how America probably sees you since I believe that it's the only song that got real airplay here—tend to resent being defined by the one song that gets cemented to their names. They tend to say, "You know, I wrote and recorded a lot of other good songs, too, you know. Hello?"

A: I've always felt that if you had to be a one-hit wonder, then "Driver's Seat" was a pretty good song to be remembered by. People still love it. It's not cheap or cheesy or formulaic. It's got a great energy. Of course, there are other songs I'm proud of, but what the hell. I would never not play "Driver's Seat."

Q: If somebody wrote a book about your life, or if you wrote a memoir, what do you think it should be called?

A: What Next?

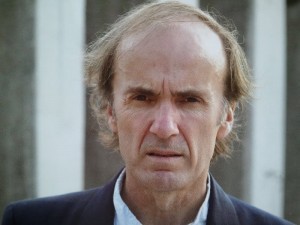

Paul Roberts, 2011

Jim Thomsen is a freelance writer and manuscript copyeditor who lives near Seattle. His clients have included well-known crime authors Gregg Olsen, M. William Phelps and J.D. Rhoades. He is at work on The Last Ferry of the Night, a literary crime novel, among other projects, but he could always use more work to pay the bills. Reach him at thomsen1965@gmail.com.