Anthony Metivier's Blog, page 15

July 7, 2021

How To Learn The Law: A Discussion With David Freiheit (a.k.a. Viva Frei)

Are you struggling to learn the law?

Are you struggling to learn the law?

If so, you might be excited to learn that even the world’s top professionals and legal experts never stop learning it.

After all, it’s always changing. And there’s a ton to keep up with.

Or maybe you, like me, just find the law fascinating.

The logic – or sometimes, lack of logic – stretches your mind. It keeps you sharp, and there are always tons of new names and terms to learn.

Well, I find the law fascinating, and have been interested in it for many years.

I’ll save the strange and mysterious story of how I once almost went to law school after making a court appearance of my own.

That’s because today I want to share with you a conversation I had with my favorite online legal vlogger… or Vlawger as David Freiheit likes to call his incredible legal analysis vlawgs on a channel called VivaFrei.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6wUdm...

I’ve been following David for a few years now, and it’s been amazing to watch how his channel has grown to include multiple platforms, including a collaborative community I belong to myself called Viva Barnes Law with Robert Barnes.

In this conversation, you’ll learn about the importance of:

HistoryTheoryAnalysisPracticeBalanceI find the work David’s doing education, inspirational and something well worth paying attention to, especially in our day and age.

Enjoy this episode and let us know if you have any question about learning the law!

July 5, 2021

Rote Learning: The Last Guide You’ll Need to Read

Are you confused about rote learning?

Are you confused about rote learning?

Some people swear by it.

Others who use memory techniques worry about “falling back on rote” despite having better tools for learning.

They even get dramatic about this worry, calling rote repetition…

“Drill and kill.”

What gives?

And how specifically is learning by this deadly form of repetition defined?

We’ll get into everything on this page so that you can make an informed decision about how to learn based on science, not opinion.

What Is Rote Learning?At its core, rote learning is defined as repeated exposure to information you want to learn without thinking about what you’re repeating.

It is almost the direct opposite of what scientists call active recall, a technique that engages all the senses.

(I’ll give you a detailed example of how to conduct multi-sensory learning at the end of this article.)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vL8Rh...

You’ll see people caught in a rut of lifeless repetition when they:

Flip through flashcardsUse spaced repetition softwareMentally repeat the same informationYou may have engaged in some of these behaviors yourself.

What makes the behaviors “rote” is literally going through the repetitions without any further level of engagement.

According to Carla Hannaford in Smart Moves: Why Learning Is Not All In Your Head, part of the success of the drug ritalin is easily explained. It helps students put up with the tedious nature of repeating information without any kind of multi-sensory engagement.

In other words, societies have preferred drugging children instead of tackling the real problem of making learning fun.

Rote Learning ExamplesBut is repetition itself bad?

Absolutely not.

For example, you can repeat prayers and engage deeply with their meaning. I’ve done this myself with Sanskrit text drawn from the Ribhu Gita for years. Each time I practice is deeply rewarding. In fact, it gets better and better the more I repeat the same material.

I also repeated my TEDx Talk several times for practice giving the speech. This is a great example of when rote repetition makes sense.

Finally, it’s really important to repeat songs if you want to commit lyrics to memory. Repetition is also a huge part of ear training, and general instrumentation a form of rehearsal musicians sometimes call “dedicated practice.”

Rote repetition can be good for ear training.

The examples of rote learning that give it a bad name include things like:

Spelling drillsMultiplication tablesCramming for examsMentally repeating names, dates or factsFlashcards for learning foreign languagesUsing appsBecause these forms of repetition can be quite brutal in how they create boredom, I.C. McManus and Peter Richards call any memory gains they create “incidental learning.”

In each case, there are alternatives. For example, you can use the pegword method to assign a dynamic shape or figure to each letter of the alphabet. This simple set of associations makes learning spelling much more fun and interesting.

When it comes to the multiplication tables, you can combine something like the Major System with rhyming or story and the method of loci to make learning the entire set engaging and immersive.

In language learning, Dr. Richard Atkinson has shown just how poorly rote learning works in comparison to the mnemonic strategies shared on this blog.

Rote repetition is normally a source of frustration. It doesn’t work well because the lack of multi-sensory engagement with personalized points of reference fails to stimulate enough of the brain.

Here’s something interesting: In experiments that have been successfully repeated by scientists around the world, Atkinson demonstrated that rote learners were successfully able to recall vocabulary from lists at a rate of 28%.

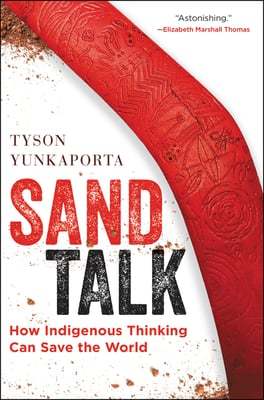

By contrast, those who used techniques like the Memory Palace showed a retention rate of 88% or better. Dr. David Reser and Tyson Yunkaporta recently showed even better results by incorporating some Aboriginal memory techniques into a follow-up experiment.

What would you prefer?

Sticking with rote learning and recalling only around 28% of what you learned correctly?

Or do you prefer what more meaningful learning and comprehension techniques offer?

Rote Learning Vs. Meaningful LearningYou might be wondering why these success rates matter so much. After all, it sounds like it really only comes down to time spent.

Looking only through the lens of time, you might conclude that if you only get 28% correct, all you have to do is go back and spend more time on the material.

Not so.

You’re also losing out on critical thinking benefits by doubling-down on rote memorization.

As Linda Jakobson has shown in her book, Innovation with Chinese Characteristics: High-Tech Research in China, societies that grow up with rote recall tend to have poor critical thinking skills.

Although it’s common for children to learn Chinese characters by rote, this learning practice has been shown to stunt critical thinking abilities.

This is tragic because problem solving requires the ability to “mentally rotate” information through multiple angles.

The absence of rote repetition in other cultures may be one reason why places like parts of Europe and the United States thrive and promote individualism and freedom.

Historically, a learning technique called Ars Combinatoria was much more prevalent. This approach promoted a form of learning sometimes called “inner writing,” a means of “creative repetition” that relied upon deep and meaningful engagement for the learner.

Meaningful learning might include tactics like:

Guided discoverySensory learningPhysical engagement with learning materials (such as through mind mapping)Social experiencesCombining writing with speakingCombining listening with speaking, such as through debateDeveloping highly personalized learning plansBenefits Of Rote LearningSo far, everything we’ve said makes rote learning look pretty bad.

However, we’ve already seen that rote practice is a must in areas of learning like music, giving speeches and spiritual goals.

When used in the correct context, rote can help learners achieve incredible goals. Playing a musical instrument is one such example.

Although rote learning reduces critical thinking when required of children, there may be some contexts where it can be helpful for certain types of adults.

For example, Po Li Tan’s research has suggested that adults who grew up as rote learners might still benefit from it.

Other research has shown that individualized learning plans can themselves fall into rote that has not benefited students in places like Sweden.

At the end of the day, each individual has to decide what is right for them and cultivate radical honesty. Sometimes engaging in rote learning gives you the benefit that you’re engaged in some kind of activity.

But if the activity of what some people call “over-learning” doesn’t actually lead to accomplishment, then the benefit of doing something for the sake of doing something is an illusion.

Disadvantages of Rote LearningThere are many disadvantages, most of which are easily avoided.

First, rote learning usually does not ask you to think about what you’re learning. It’s focused entirely on repetition itself.

This focus not only makes it boring, but you lose out on the benefits of thinking you could receive by engaging with the information in a deeper way.

Line rote also treats the brain like a “linear library.” You miss the benefits of what I often call the “rhizomatic effect” you experience when using a Memory Palace Network to produce new knowledge based on information you’ve engaged with deeply.

Your mind is not a library. Avoid treating your memory in a linear fashion.

You also lose tons of time that could have been spent enjoying using your mind and imagination.

Finally, rote repetition prevents you from experiencing the benefits of having memorable conversations with others.

The Alternative To Rote LearningIs rote learning effective?

To a certain extent, yes.

And in some areas, rote rehearsal is absolutely necessary, including when you’re using memory techniques.

However, repetition should always be “creative repetition.”

A simple way to reduce the amount of repetition needed and always ensure that you deeply immerse yourself in what you’re learning is to use KAVE COGS or what we call the Magnetic Modes in the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass.

To take a simple example of how I learned something very quickly with a minimum of repetition, let me refer to my Sanskrit meditation project.

In learning a word pronounced like “tesham,” which means “unto them” or “for those,” I didn’t repeat it over and over again.

No.

Instead I looked at the “tes” part of the word and imagined Nikola Tesla driving a Tesla over a Christmas ham. He did it for those who are always devoted to reality itself, which is the main meaning of the entire line I was learning.

A simple, but engaging mnemonic image like a Tesla driving over ham makes memorizing a word fast, easy and less likely to need rote repetition.

Then, I went through KAVE COGS to drive home the sound and meaning:

Kinesthetic – Feeling myself driving the car as if I were TeslaAuditory – Hearing the sound of the engine roaringVisual – Imagining what this scene looked likeEmotional – Experiencing Tesla’s intention to help the devotedConceptual – Reflecting on the meaning of the text and who Tesla wasOlfactory – Smelling the hamGustatory – Tasting the hamSpatial – Thinking about the size of the car and the hamBy engaging deeply with the word in this way, I learned it immediately and never forgot it after one pass.

I’ve memorized more Sanskrit than I ever thought possible doing this, the same technique I learned to use when memorizing the names of all my students within minutes when I was a professor.

So if you’re sick of boring, old and uninteresting methods of rote memorization, why not give this free course a try?

Memory techniques are scientifically proven and indescribably fun. All you have to do is get started.

So what do you say?

Are you ready to rev the engine of your mind and get some real learning done for a change?

June 30, 2021

How to Learn Something New in 6 Easy Steps

Let me compliment you on wanting to learn something new.

Let me compliment you on wanting to learn something new.

In a world of indifference, so few people take action, let alone search for how to take action.

Then there’s the question of what to learn. This can itself be quite challenging because there are so many options out there.

Well, on this page we’ll simplify everything by talking about how to learn a variety of things. Not all skills are learned the same way, after all.

And to start eliminating the confusion about how to learn, let’s boil things down to a simple formula:

S.I.P.

StudyImplement PracticeOnce you pick what you want to learn, you study to find out the steps involved. Then you implement those steps, followed by practice to improve your execution.

With this process in mind, let’s get started.

Why You Should Learn Something NewOne word:

Longevity.

Learning things literally promotes cellular growth in your brain. It also strengthens the neural connections you already have.

If you go the language learning route, some studies in bilingualism report up to 32 years in brain fortification. This benefit means that your brain gets protected from diseases like Alzheimer’s and Dementia.

Other reasons you’re right to say, “I want to learn something” include:

Getting a raise or promotion (like Jesse Villalobos)Winning a competition (like James Gerwing)Speaking a language in another countryStudying effectively so you can pass an examSpending time offline to fend off digital amnesiaImprove your reasoning abilities

To put it another way:

If you want to continue learning for the rest of your life, always learning something new is the best way to keep your mind and memory short.

And the more you know, the more you can know.

How to Learn Something New: A Proven 6-Step ProcessNow, we’ve seen that to learn we need to take it one S.I.P. at a time.

But what are the exact steps?

There will always be nuances for different things you want to learn. But generally, here’s what you need:

Step One: A VisionBefore planning anything or buying books, it’s useful to sit down and imagine the desired outcome.

For example, if you want to learn how to improve your memory, you can craft a memory improvement vision statement.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFz31...

The reason it’s important to do this is that it helps you know your “why.” That way, when certain parts of the journey get tough, you’re able to keep pushing through.

And never give up when you’re challenged. No doubt, obstacles can create resistance. But it’s when we push through challenges that growth occurs. This cannot happen if you quit.

Crafting a vision statement also helps you test through your conviction. There’s often a difference between what we want and what we’re actually willing to do.

When spending some time on your vision, you can dodge a lot of speeding bullets. You can also think through various alternatives.

Pro tip: If you don’t like linear prose, one great way to craft your vision statement is through mind mapping.

Step Two: Plan WiselyAfter testing your conviction by crafting a vision statement, it’s time to plan.

In this step, you’ll set aside time to research what you want to learn.

During this phase, you’ll identify books, courses and key experts who can help you achieve your vision or desired learning outcome.

Then, you’ll chart out when you’re going to go through those materials or meet with the expert trainers who can help you.

Pro tip: If you struggle to plan and schedule your time, getting help from a coach can be a game changer. There’s no shame in lacking discipline and knowledge in this area.

So if you have a vision but struggle to plan and implement, find someone who can help you make it happen. Life Coach Spotter has a great guide that can help you find the perfect person.

Step Three: Define The ProjectI’ve already talked about spending some time identifying your books and courses.

This should help you define the scope of the project.

To do this, state how much time you’re going to spend and how much material you want to get through.

For example, when I started my Art of Memory learning project, I devoted six months to it. I committed to reading one book on the topic per week and at least two articles.

By giving your learning commitments definition in terms of both scope and duration, it’s so much easier to achieve specific goals.

You can even create certain milestones. For example, if you’re learning about a topic that has multiple authors writing about it, pick one author. Read just their major works as a milestone before moving on to the next author.

Step Four: Plan To FailSounds weird right?

Not at all.

As I mentioned, there will be challenges when learning anything. And that’s why we need to have a plan for what to do when those challenges arise.

The choices you make can be quite simple. For example, when I reach a point of frustration, I almost always take a walk. “Go for a walk,” is my auto-pilot mantra and it helps refresh the mind.

I also like to have “attitude adjusters.” Many of my journals come with motivational quotes printed on each page. I follow lots of positive quote Twitter and Instagram accounts and motivational speakers. Constantly fueling positivity helps so much.

Step Five: Take Effective Notes And Keep A Learning JournalThere are so many approaches to note taking. It can be frustrating trying to find the best option.

At the end of the day, I suggest you experiment with a few different styles. Combine what you find works best with the Memory Palace technique for best results.

Keeping a journal is important too. Here’s why:

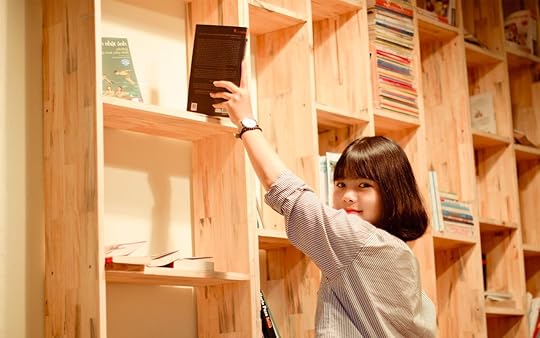

Learning is a lot like art.

And artists always sketch in journals.

They do this not just to practice. They do it so they can look back and see just how far they’ve come.

Instead of always filling your journal with notes about what you’re learning, try this instead:

Fill your journal with the questions you have along the way. Then work at answering them.

When you look back, you’ll find that you’ve grown incredible, and the Q&A process with yourself will have paid many dividends.

By the way, this process of asking yourself questions and working to answer them is called The Feynman Technique. It’s just one of 28 ways I’ve compiled in How to Study Effectively.

Step Six: The Big Five Of LearningFinally, it’s important to integrate everything. For that, we pull all the big guns together:

ReadingWritingListeningSpeakingMemorizationBasically, this process means that you deeply integrate what you’re learning through ample discussion and follow-up in multiple ways.

For example, to integrate what you’re learning, a discussion group helps you reflect on your own thoughts while appreciating the varying viewpoints of others.

Writing, as we’ve seen through journaling, helps you identify and answer any questions you have.

And memorizing makes sure that everything you learn remains for the long term.

What New Things Should You Learn?If you’re not sure what to learn, here’s a master list of suggestions. It’s possible to pick up skills in each of these in a single lifetime.

But as always, it helps to focus on just one skill at a time. Keep the lesson above about scope and definition in mind when choosing what you want to learn.

Typing

“All wealth comes from writing.”

That’s a quote I heard a long time ago, and I believe it’s true.

Whether it’s writing books and articles or just an effective networking email, it helps if you can do it quickly.

If you don’t know how to type, I’d suggest starting with this foundational skill.

LanguagesI’m a big believer that everyone should speak at least one other language. It’s not only good for your brain, but hugely beneficial for your wallet.

As reported in the BBC, knowing at least one other language can add more than six figures to your wealth every four years.

The best part is that it’s incredibly easy to learn any language, even without leaving your home.

EconomicsUnderstanding exactly how money makes the world go round is hugely beneficial.

It not only helps you earn and save more. It helps you avoid mistakes and reduces your stress about market changes.

Marginal Revolution is a leading blog that aggregates links from around the net relating to economics. You can learn a ton just from following its links and book recommendations.

NumeracyIf you’ve ever wanted to start a business, you’ll need to know at least something about math.

Knowing your numbers is also useful for:

AccountingInvestingStatisticsProgrammingAnd that’s just to name a few areas.

One fun and easy way to make math fun and exciting is to learn Chisanbop.

Music

What can be more pleasing than being able to pick up an instrument and accompany yourself as you sing a song?

There’s another benefit:

When you know how to memorize a song, singing produces healing chemicals in your body. Playing an instrument exercises your brain, which means that bringing them together is even more beneficial.

DrawingI used to hold the limiting belief that I could not draw.

But I wanted to and within a year was stunned by the progress I’d made.

Riven Phoenix has a great course on drawing the human figure I highly recommend. It’s helped a lot with my visualization skills tool.

PsychologyLearning how and why your mind operates helps you enjoy life a lot more.

There are many mental models to discover, not to mention sorting out your cognitive biases.

Knowing about psychology also boosts your ability to think in a reflective way. Mulling over topics is fine, but doing so with knowledge of how your mind functions boosts the entire process.

Survival Skills And Bushcraft

Sure, few of us will wind up lost in a forest or stranded in the desert.

But you never know, do you?

If you’re casting about for something to learn, these skills will keep you prepared for even the most unlikeliest of events.

Podcasting And Video Course CreationEveryone has to run errands and most of those people are listening to either music or podcasts while doing them.

Why aren’t you the one in their ears?

Simple:

You haven’t learned podcasting yet.

I’ve been running a podcast since 2014 and have hardly missed a week. If you want to learn from me about how to do it, check out my course, Branding You. It’s been a bestseller on Udemy since it was released in 2015.

SEO And BloggingLearning how to rank posts on page one of Google is an art, craft and science.

You can turn it into a career or just do it for fun.

But the name of the game either way is to have an audience.

And that’s where learning to write for both humans and the search engines come in. It’s a great learning project and one I highly recommend.

Here’s why:

It makes you a better writer overall. When you can learn to reach people through both search engines and peaking their interest once they’ve found you, those skills apply to:

BooksSpeechesPodcast episodesYouTube video scriptsOnline course contentGive this skill a try!

Public SpeakingWhen I wrote this TEDx Talk, I had no idea it would reach over one million people.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kvtYj...

But it did, and having taken a course on public speaking helped.

I’m not the greatest speaker, but I’m glad I spent the time learning how to present.

If you’re worried you’ll forget your presentation, please don’t be. Here’s how to memorize a speech (and deliver it without sounding like a robot).

The LawThe vast majority of people can’t read the law that governs them. That means they can’t participate in shaping the rules they follow.

But even just a little knowledge of the law can go a long way. It helps you communicate with your representatives better, for one thing. And you can keep them more accountable in the first place, something obviously not enough people do.

It sounds cliche, but we all need to be the change we want to see in the world. Remember: Gandhi was a lawyer first. This background was a key part of his civil rights activism.

LogicIf you do start learning the law, you’re going to get logic as part of the package.

But you can also learn it as a topic and skill on its own.

Why bother?

A few reasons:

Reasoning through whether arguments are objective or subjective is a valuable skillYou can persuade others more effectivelyLearning logic is a major intellectual achievementYou’ll spot fallacies fast and avoid devastating problemsYou’ll become clear and precise in many areas of your lifeThe media becomes easier to interpret, freeing you from irrational beliefsAnd that’s just for starters. I highly recommend learning all that you can about logic. Here are some critical thinking exercises to help you get started.

NetworkingOf course, all of the above suggestions will be of limited use if you don’t have anyone to share your skills with.

That’s why learning to become a well-connected person is an important skill to learn.

Of course, “networking” isn’t necessarily the right word for it. Often people associate it with business-types trying to find new clients.

As Jennie Gorman puts it, “netweaving” is the alternative. In this approach, you’re there to give to others, not to figure out how you can benefit.

And when you’ve learned something new, being in a position to give is exactly where you’ll be.

Best Websites to Visit to Learn Something NewNow that you have some ideas in mind, here are a few suggested websites for learning new skills.

Obviously, there are thousands of choices out there. To help narrow it all down, don’t forget to craft your vision, define your plan and take some notes on which resources you want to investigate further.

Learning How To Learn ResourcesLearning How to LearnHow to Study EffectivelyLanguage Learning ResourcesI Will Teach You A LanguageFluent in 3 MonthsBest language learning softwareInternet Writing, Podcasting And Course Creation ResourcesSmart BloggerNeil PatelCreating Valuable Video Content That SellsMusic ResourcesMusic theoryFret Fury (guitar)PianoCourse Aggregators (Various Resources)UdemySkillshareLinkedIn LearningThis Free Masterclass Can Help You Learn New Things FastAt the end of the day, every learning goal places huge demands on your memory.

But that doesn’t mean you have to struggle.

In fact, there’s a special way to approach learning using an ancient tool. We’ve already mentioned it above.

If you’d like a free course that takes you through the fundamentals, learning to master your memory first is a great idea.

To get started, just let me know where to send you Memory Palace Mastery. It’s four free videos with three worksheets in the form of a Memory Improvement Kit:

So now, what do you say?

Are you ready to go out there and learn something new?

I hope you feel more empowered and focused now than just casting about to learn stuff.

I hope you have the tools to bring laser focus to the learning topics you choose so that you can truly soar.

June 23, 2021

What Is Active Recall and Does It Help You Remember?

Have you heard the hype about active recall, but still feel skeptical?

Have you heard the hype about active recall, but still feel skeptical?

Or maybe you’ve heard the latest “learning guru” say that this recall method is better than the Memory Palace technique.

If that statement has gotten your hackles up, I can’t blame you.

After all, the Memory Palace, when used correctly, is active recall and self testing all rolled into one.

So where does the confusion come from?

Should you use Anki instead of one of the ancient memory techniques?

Are there exercises for improving active recall?

Well, if you want information to “stick” permanently, then stick around. We’ll get into the answers to these questions in-depth on this page.

What Is Active Recall?Here’s the best scientific definition I’ve found so far:

Active recall is a personalized recall strategy that involves variety.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Um9S6...

In other words, spaced repetition software might help you use active recall. But it can only help you and pales in comparison to what personalization with variety can do for you.

And that’s where the memory techniques taught on this blog come in.

Here’s what I mean with an example:

This morning I learned 态度 (tàidu). It’s Mandarin for “attitude” or “manner.”

To use active recall and spaced repetition to rapidly place the sound and meaning of this word into my long term memory, I followed these steps:

Memory PalaceElaborative encodingRevisiting the Memory PalaceElaborative decodingSpeaking practice in a sentenceWritingReadingListeningTechnically, the “active recall” part happens only during the attempt to recall the information.

However, we know from memory athletes like Boris Konrad, that active recall is a lot easier when you use personal associations to “encode” information. He’s a neuroscientist too, so his views are very valuable.

If you have difficulties with coming up with associations, consider learning how to image stream the Magnetic Memory Method way.

Retrieval PracticeAnother way of looking at the recall part is to use the term “retrieval practice.” When I recall the association I made in the Memory Palace for this word, I’m practicing one level of retrieval. Speaking and writing the word are other levels. Pulling up the meaning when hearing the word through listening is yet another level.

The reason retrieval practice at multiple levels helps your brain form memories faster is simple. The more levels of recall you engage, the faster your brain makes multiple connections.

This has been called the “levels of processing model” and works for just about everyone. People with schizophrenia may struggle, however, no matter how much active recall they perform.

Does Active Recall Really Work?In a word:

Yes.

The real question is:

Are you doing it?

And if you’re doing it, are you doing it in a deep or shallow way?

If you’re using Anki or some other flashcard app and not using elaborative encoding, then that is a passive and shallow way to engage with what you’re learning.

But if you at least make personalized associations for each and every piece of information, your recall rates will soar.

In order for active recall to work, your associations need to be personalized and varied. You are a living being, not a programmable computer, so if you use software, always personalize how you use it.

(Side note: There is a place for passive memory training, and it is shared by Dr. Gary Small. It’s very powerful for its intended purpose.)

Why Active Recall Works In Any LanguageOne of the key researchers to know about is Dr. Richard Atkinson. He has shown 88% retention rates for those who use elaborative encoding. That’s compared to 28% recall for those who don’t.

Here’s more on retaining information efficiently.

You can also learn more about why features of human language make this process work, and see it reproduced for students with different mother tongues. For example, Dr. Horst Sperber has reproduced these research findings for German speakers with ease.

In other words, the language you speak doesn’t matter. It’s your strategy with this recall method that makes all the difference.

So the question isn’t really whether or not these techniques work. The question is:

How do you make sure you are always using active recall in a deep way?

Active Recall Strategies While StudyingThe trick is to learn how to encode quickly, place the associations you make into Memory Palaces and then remember to decode using active recall.

Luckily, all of this can be “automated” through habit formation.

Step One: Have Your “Palette” PreparedThe first habit to develop is having enough Memory Palaces and then thinking of them as you learn.

To get started with this, make sure you have enough of them. My free course will help you:

When I’m encoding, it takes just a second to think of the Memory Palace for a word like 态度 (tàidu).

Since its core meaning is “attitude,” I thought about a lecture hall where I’d seen Margaret Atwood give a lecture.

Attitude and Atwood share a core sound. And if you’ve ever seen her speak, you know that she’s definitely a woman with an interesting attitude about many topics.

Step Two: Have Your Encoding Materials PreparedA word like 态度 (tàidu) can be broken down into pieces: tài and du.

If you use the Magnetic Memory Method, you’ll have associations ready to go based on the alphabet. I just thought about Attwood wearing a tie made of doodoo.

Here’s more on using a “Magnetic Alphabet” to rapidly encode information:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=caCUF...

Step Three: Elaborate All Of Your AssociationsFast associations generally aren’t enough. You need to elaborate on them in a multi-sensory way.

We do this through a process called KAVE COGS. Each of the letters stand for one of the “Magnetic Modes.”

Let me take you through the process with 态度 (tàidu) as an example.

Kinesthetic: Physically feeling the weight of this tie on Atwood’s neck.Auditory: Hearing the sound of her voice having a bad attitude about the situation.Visual: Thinking about what the scene looks like.Emotional: Experiencing her disgust at having a tie made of doodoo.Conceptual: The fact that Atwood is an author is a concept itself, but I add on the idea that her next book is called “Attitude” and is about someone forced to wear a tie made out of doodoo.Olfactory: The smell of the tie is all too easy to imagine.Gustatory: So is the taste – yuck!Spatial: This is where you spend a second thinking about the sizes of things involved in the association. In my imagination, this tie is rather tiny.With practice, using KAVE COGS should take only seconds.

For a simple exercise, try to remember that a sound like tai (as in Thai food) and du mean attitude in Mandarin Chinese.

Encoding with highly personal experiences like eating particular kinds of foods makes active recall much easier.

Come up with your own multi sensory associations and then after five minutes, see if you can bring each association back to your mind.

Step Four: Purposefully Bring Back The AssociationThere’s no cookie cutter answer for how to do this.

Memory expert Dominic O’Brien suggests the Rule of Five, but I’ve never found a specific description of how he does it.

Myself, I make sure to just start recalling the information.

When I’m learning Chinese, I use new words and phrases in conversations with my wife.When I’m learning history, I pepper the facts into my writing and conversations.I recall in the shower.I practice active recall while walking. I apply the recall method in a journal I use for testing. I keep using active reading to instil the source material of the information.I continue listening to relevant audio and visual programs.Etc.The important point is that recall happens in multiple formats and locations. It really helps that some of the active recall takes place out on walks, for example.

Step Five: Use Recall RehearsalThe absolute best way to use active recall is by following patterns that maximize the primacy and recency effects. These are the laws of memory that help us build mental connections faster and ensure that they last.

This process also harnesses the serial position effect and the Von Restorff Effect.

There are 5 key patterns for using active recall with a Memory Palace. Please make sure you use them all.

To use it, you mentally travel in your Memory Palace using different patterns. On each station of the Memory Palace, you use active recall to decode your associations and bring back the target information.

Here are the patterns:

Beginning to endEnd to beginningMiddle to endMiddle to beginningSkip the stationsIf you keep your Memory Palaces small, or at least segment them, you’ll find this process easy and fun to do. And it’s incredibly effective too.

Step Six: Use QuestionsWhen revisiting the Memory Palaces, exactly how to trigger recall can be a silent process. You can simply bring the location to mind and let the association you created replay.

But sometimes things don’t start up so smoothly.

And that’s where I suggest you learn to use a simple “decoding” question.

What was happening there?

If this question doesn’t help you start recalling the information, then you can start self testing using KAVE COGS.

What was the kinesthetic association I made?What was the auditory association? What was the visual association? Etc.Usually, you won’t have to ask many of these questions. And the questions are a great “cheat detector” that expose when you’ve tried to take shortcuts by not using all of the Magnetic Modes built into KAVE COGS.

When that happens, just add them in. This will probably fix the problem and improve your rate of recall quickly.

Step Seven: Develop More Advanced ApproachesAs you develop with these skills, you’ll want to be able to encode while reading.

Usually, I extract the information from books I’m studying onto cards. I taught this process in How to Memorize a Textbook.

But if you want to practice a skill that releases you from this, you can turn each page into a mini-Memory Palace on its own.

You can do this by developing a 00-99 PAO, which is a variation on the pegword method.

Let’s say that you encounter a fact. For example, I’m currently reading Adam Zamoyski’s Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth.

To remember that Napoleon was born in Corsica, I use 09 because it’s on page 9 that I encounter this fact.

My image for 09 is Brad Zupp driving a Saab. To elaborate this image to recall “Corsica” I imagine him throwing an apple core about the window. I place this image not in a traditional Memory Palace, but at the top of the page.

Later, when I want to remember that Napoleon was born in 1769 and died in Longwood in 1821, I can add these facts to the middle and the bottom of the page.

Using mnemonic devices to help with active recall is great for facts like historical dates, people and locations.

Then, when performing active recall, I have page 9 to easily refer back to as the “palette” where I “painted” the associations.

Although this technique is a bit more advanced, it does not mean you can skip Recall Rehearsal. You just wind up using it a different way as you mentally revisit the pages of the books and your associations in them.

Why Mastering Active Recall Is A MustAs we’ve seen, the Memory Palace technique is a great way to use Active Recall.

To call it an alternative to flash cards and spaced repetition software would be a mistake.

Or better said, it’s the other way around. Leitner boxes, Anki, Quizlet and other programs are the modern alternatives to this ancient technique.

But do they work as well?

They certainly can, provided you engage deeply with the elaborative encoding steps I’ve shared with you today. However, I’m confident you’ll find they work even better if you strengthen your spatial memory using the Memory Palace technique.

In sum, here’s the takeaway to remember:

Active recall studying throughout the day is totally possible. You just need to set up your memory systems.

But it’s technically not to be called “active recall” if you’re not making highly personal associations that help you recall.

And you need to be reading, writing, speaking and listening in ample doses to make sure you’re actively recalling through multiple channels of your mind.

So what do you say? Are you ready to approach active recall and spaced repetition in a new way?

June 16, 2021

Aboriginal And Indigenous Memory Techniques with Tyson Yunkaporta

Are you curious about the memory techniques used in the ancient world?

Are you curious about the memory techniques used in the ancient world?

I’m talking about aboriginal memory techniques in Australia.

But also a lot more.

For example, it’s possible to learn about all sorts of indigenous tools for learning and retaining information used by people around the world.

If this sounds interesting to you, you’re in luck.

In this episode of the Magnetic Memory Method Podcast, I sat down with Tyson Yunkaporta, an author and educator who has shared these techniques with many groups of people.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R_–IA...

Tyson’s a huge fan of both the Aboriginal memory techniques and the Memory Palace, so I think you’re going to love how we discuss all the techniques we go over in this discussion.

As the author of Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save The World, Dr. Yunkaporta is an incredible teacher.

I found this book compelling, useful and the main mnemonic device taught in the book is an obvious win for social change and healing global issues.

As Tyson expresses in this interview, the time for “memory wars” (and all kinds of other wars) is over.

We simply don’t have time for them anymore.

And to help you be part of the solution in your culture, you need to widen your context and bring that back into your community.

Here are just some of the memory techniques you’ll discover in this discussion:

Real places and objectsRelationalHaptic connectionsRiddles and wordplayThe Night skySonglinesPlace and maps of placeSymbols and imagesRhythm and rhymeRepetitionSongRude languageStoriesMessage sticksIn sum, if you were to put these mnemonics into play, you’d be using them as a “way of life.”

For more on the scientific study that inspired this “yarn,” please see my discussion with Dr. David Reser:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UkDgT...

I also recommend you supplement this video with Brilliant Miller’s interview with Tyson:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JCzlg...

Lynne Kelly and her books The Memory Code and Memory Craft comes up in this interview, so if you’d like to catch up with me and her, please see:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jim_c...

Finally, here’s The “Memory Wars” recording with Dr. Reser and Dr. Yunkaporta.

We talk about a number of mnemonic devices in this interview, so please be prepared to write them down. Songlines are part of a larger set that people used who had a ton of knowledge they needed in order to survive.

Make sure you supplement your own survival by digging as deeply as you can into the wide range of techniques history around the world has to offer. And apply the information you acquire to helping the world become a better place.

Thanks for being part of the memory world at large and talk soon!

June 9, 2021

10 Types of Synesthesia (Examples, Causes, and Symptoms)

With so many types of synesthesia out there, it can be hard to understand exactly what it is.

With so many types of synesthesia out there, it can be hard to understand exactly what it is.

That’s why it’s important to look at the word itself first:

It shares a root with anesthesia. This word means “no sensation.”

“Syn” means that something is joined or coupled together. Thus, synesthesia means the joining or coupling of two or more sensations.

And because many different kinds of sensations can be joined, that’s why there are so many synesthesia types.

On this page, we’ll go through the definitions of each one. You’ll discover specific examples and interesting tidbits from scientific research.

That way, you can leave with the fullest possible understanding of this condition. You might even be able to invoke it too using a resource I’ll share below.

Let’s get started.

The 10 Types of Synesthesia (with Examples, Causes, and Symptoms)In his book on the topic, neurologist Richard E. Cytowic states that approximately 4% of the population experience some form of synesthesia.

Exactly how long people experience their synesthesia is unknown, but many seem to drift in and out of it.

In Wednesday Is Indigo Blue: Discovering the Brain of Synesthesia, Cytowic and his co-authors David Eagleman and Dmitri Nabokov found that evolutionary pressures may shape when and for how long a synesthesia condition affects people.

The condition also tends to be unidirectional. As they point out, a person might experience the letter J as blue. However, seeing blue does not cause them to think about the letter J or experience “J-ness.”

Most forms of synesthesia belong roughly to what some people call “Projection Synesthesia.” That is, something in the brain causes their minds to project senses that aren’t there for the rest of us. Often they tend to involve colors.

So with these aspects in mind, let’s dig into as many types of synesthesia as we can.

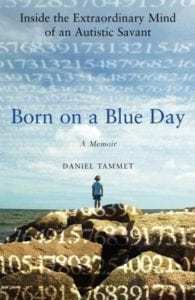

One: Colored Days of the WeekHere’s how Daniel Tammet discusses his birthday:

“I was born on January 31, 1979 — a Wednesday. I know it was a Wednesday, because the date is blue in my mind and Wednesdays are always blue.”

In his book, Born on a Blue Day: A Memoir of Aspergers and an Extraordinary Mind, Tamet says that Tuesday is a “warm color” and Thursday is “fuzzy.”

This lack of specificity for some days of the week should remind us of the consistency issue raised by Cytowic. Or it’s possible that some days have substances for Tamet rather than colors.

Is this the same as associating numbers with colors. Not necessarily. For that we need to learn more about our next type.

Two: Grapheme Color SynesthesiaWhen you see or think about the letter “A,” does it have a color? For some people it does. Likewise with numbers.

Some people will read letters and numbers and see them as colors. Others with grapheme color synesthesia will see letters and numbers as black marks on white paper but think about them as colors.

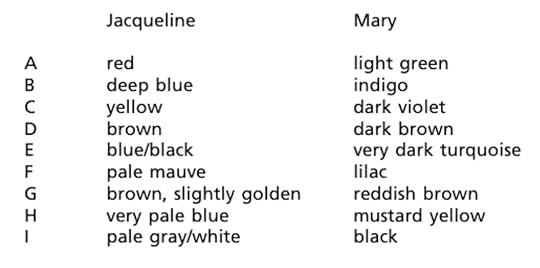

In The Frog Who Croaked Blue: Synesthesia and the Mixing of the Senses, Jamie Ward gives a list of letter-color associations from two research participants.

It is interesting that different people experience these letters in different ways. This suggests just as much nurture in the development of this form of synesthesia as nature.

Three: ChromesthesiaChromesthesia, or colored hearing, means that the individual experiences colors connected with sounds.

Researchers have found that sounds can trigger more than colors as well. A person with this condition might hear music and experience shapes, landscapes or textures.

Composers who may have drawn upon this type of synesthesia include Franz Liszt and Jean Sibelius.

Four: Ordinal Linguistic PersonificationIn this manifestation of synesthesia, the individual will experience numbers, days, months and multiple kinds of words and things as if they were people.

For example, the word “camping” might be experienced as having a gender and a tendency towards grumpiness. A stick on the street might seem to the individual as a happy young man.

In many ways, this synesthesia condition is a lot like how kids play with objects to keep themselves entertained.

Five: Mirror TouchImagine you see two people across the street shaking hands. But you don’t just see it. You feel it as if you were the one shaking hands. That’s what is meant by Mirror Touch synesthesia.

In a two-year study by Charlotte A. Chun and Jean-Michel Hupé, these researchers found that many kinds of people with synesthesia experience this form. There was no way to predict which kinds of people might have this kind, but they did see some indication that French people were more likely to experience grapheme color synesthesia.

Six: Spatial Sequence SynesthesiaThere are at least two parts to Spatial Sequence Synesthesia, sometimes called “Number Form” synesthesia.

First, the person experiences numbers units as having distinct locations. For example, take an organizational unit like a calendar. Instead of thinking of February conceptually as a group of days, the person will experience it bound up with a location, or as if it had the qualities of a location.

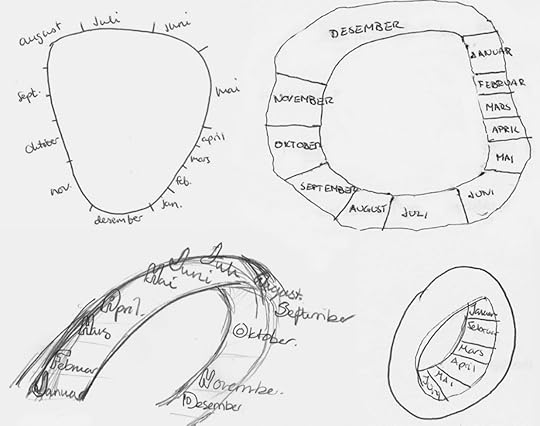

Mark Price and Jason Mattingly give an example of calendar drawings in Automaticity in sequence-space synaesthesia.

Second, this unit will be experienced with references to other numbers, themselves located in space.

Jamie Ward asked a test participant to draw how she was experiencing Spatial Sequence Synesthesia.

As you can see, the participant not only has the numbers represented where they appear in space. She has indicated how she can rotate her point of view around their location.

Another point:

Part of experiencing this form of the condition might mean that people experience numbers “floating in space at a fixed distance from their body.”

Seven: Auditory-Tactile SynesthesiaAlso called “Sound-Touch Synesthesia,” this form of the condition means that common sounds create physical sensations in the listener. These are typically described as “tingling” and may be intense enough to deeply disturb the individual.

Studies in people with thalamic lesions have shown that this part of the brain might be responsible for both physical and sound sensations. This area of knowledge is one place where knowing how to remember the cranial nerves could also be helpful because they contribute to some of our ability to perceive physical and auditory sensations.

Eight: Lexical-Gustatory SynesthesiaImagine tasting the words of this article as you read it.

That’s exactly what would be happening to you now if you had lexical-gustatory synesthesia.

Researchers have found that amongst the few people who experience this condition, the experience is very intense but lacking in quality. Brain scans show that the parts of the brain involved in emotions light up, which may explain the magnitude of these experiences.

Sound-gustatory is much the same. However, in this case, the sense of taste is triggered by noises and auditory modulations in the person’s environment.

We’ve talked about taste. What about smelling colors?

This too is something that happens to people with synesthesia, but seems much less common than some of the other types.

Although subjective feelings are involved in each of these, it’s hard to say if any of them amount to emotional synesthesia as a type on its own. More research needs to be done, some of which is being uncovered by those investigating our next type.

Nine: Misophonia SynesthesiaPeople with misophonia can be triggered to rage by everyday sounds.

Researchers have not been able to find out much about it. Some conclude that many people fail to report their symptoms for fear of being stigmatized.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, ASMR has been all the rage over the past few years. Videos featuring all kinds of mundane sounds of racked up millions, if not billions of views on YouTube hoping to induce “auto sensory meridian response.”

These are pleasant tingling sensations that come from listening to sounds like whispering voices, tapping, blowing bubbles or chewing gum.

Ten: IdeaesthesiaOf these two images, which would you name Booba and which Kiki?

Most native English speakers will name the image on the left Kiki and the image on the right Booba.

Why?

Because hard-K sounds are conceived as being similar to sharp angles. Softer B-sounds are generally perceived as more like the rounded drawing to the right. According to Derren Bridger, marketers have long known about this tendency and used it to help dream up product names.

Much more research needs to be done on this branch of synesthesia. It’s not yet clear if colors are also involved in how people might experience these conceptual approaches to linking sounds with shapes in a conceptual way.

Can You Give Yourself Synesthesia?I don’t think so. And I hope you never harm your brain or develop a lesion that might come with unwanted effects just to experience synesthesia.

However, you certainly can increase your ability to experience the world in a multi sensory way.

To give this a try for yourself, go through this hyperphantasia guided meditation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uAz3_...

In the meantime, I hope this rundown of the many different types of synesthesia helped you out.

If there are any I missed, please pop them into the discussion area so we can all learn about them. And if you’d like to be able to memorize all of these different terms we discussed today, check out my FREE Memory Improvement Kit today:

June 2, 2021

Better Than The Memory Palace? A Discussion With Dr. David Reser

Tell me if this sounds like clickbait?

Tell me if this sounds like clickbait?

“Ancient Australian Aboriginal Memory Tool Superior to ‘Memory Palace’ Learning”

I mean, I thought so too.

Must be click bait.

I grew even more concerned when Dominic O’Brien tweeted a Neuroscience article and added this statement:

“In short, Link or Story Method combined with Journey Method provide the optimum learning strategy.”

With all due respect to Dominic and acknowledgement of his great accomplishments and wonderful books, this is not precisely what the Neuroscience article says.

Nor is it what the full study says.

Neither the media report or the study even contain the word “Journey.”

An Opportunity For The “Pause” ButtonNow, because I’m human too, I decided not to battle about this on Twitter. As you know, Angry Birds just ain’t my schtick.

In fact, I simply retweeted Dominic’s statement with a link to the original study.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UkDgT...

And with sincere humility, let me offer this:

For a memory expert to… shall we say… shape what a study says by promoting it with a quasi-branded term like “Journey Method” should be a wake up call to the human and humanness in us all.

Because as educators, it’s normal to get excited by anything in the world of science that validates what we’ve been saying all along. I’m sure in haste I’ve done something like that too, and in this fast paced world, probably will again.

All the more reason that we must be on our guard and seek to go beyond the headlines and the tweets.

To temper ourselves so that we can truly learn from the research, and hopefully improve how we teach and learn, while avoiding getting territorial in ways that risk placing borders on the wonder.

Territorialism Over TerminologyBecause frankly, I noted a small tremor of territorialism in myself at the idea that something could be better than the Memory Palace.

And that happened to me even though I often remind you that this term is just a word for location-based mnemonics, and nothing more.

Knowing that there must be more to this study than anyone could hope to convey in a tweet, I read the full paper myself. And to get even more detail, I reached out to Dr. David Reser at Monash university.

As a neuroscientist with interests in attention, consciousness and many aspects of education, Dr. Reser is the head author on the study that several dozen people have emailed me about since the story broke.

What Does The Study Actually Say?First off, it’s important that you read it yourself.

The study is called:

It turns out, the medical and health education setting matter a great deal. And there are several more nuances that make this study very, very interesting.

For example:

A particular story was important to the studyStudent preparedness and preexisting learning experiences may be key to learning fasterHaving a teacher in the learning space with the students was importantThe Aboriginal approach is shown to have helped the individuals remember the order betterMore research on long term comparisons with the Method of Loci and the Aboriginal technique are requiredThese are just my tentative bullet points for the time being.

Frankly, Dr. Reser is so good at explaining the science, I really hope you’ll dive into the full conversation.

This Actually Could Be “Better” Than The Memory Palace TechniqueFor now, I’m happy to say this:

If all of us educators and students can get on the same page, share these findings around and collaborate with those members in the Aboriginal community who hold knowledge we should be very excited about…

Why then, there might just be something many magnitudes of better, better than whatever you want to call the memory techniques you currently use.

But we do have to pay the price of attending to accuracy.

With care and accuracy in mind, I’m grateful Dr. Reser spent this time with us to discuss the study, the nature of its implications and what we all can do to learn, explore.

Links To Dr. Reser

Please spend some time on the reading, share your thoughts in the comments.

And if you’re new to the Magnetic Memory Method blog, please get subscribed because I’m hoping to record a follow-up interview with Tyson Yunkaporta soon.

If you, like me, care about the memory tradition and our quest for the truth about what really works, you’re not going to want to miss a thing.

May 26, 2021

How To Stop Losing Things: 6 Proven Tips

If you want to stop losing things, you’re probably tired of the standard advice.

If you want to stop losing things, you’re probably tired of the standard advice.

Sure, tips like getting more organized, reducing clutter and always placing things in a designated spot make sense.

But everyday life does not make sense. Sometimes we put things down and can’t remember where we put them.

So what really works?

Well, if you’re sick of constantly losing things, you’re in luck.

On this page, we’ll go through some proven memory techniques you can use. They’ll help you remember where you placed things even when you cannot follow the standard advice.

How to Stop Misplacing ThingsFirst, we need to start getting more specific.

Instead of “things,” we need to start using the actual names for what we want to stop losing.

And the topic of naming leads us to our first major tip.

One: Say Names And Locations Aloud

If you have to set your keys down, say aloud, “keys on the counter.”

This will reinforce the action and help your brain label both the object and the location.

If you tend to forget whether or not you locked the door, saying aloud “locked” will help. It’s so much easier to remember what you’ve said aloud compared to what you’ve done physically.

Rest assured, there’s no shame in this. I’m a memory expert and I say “locked, locked, locked” in my mind almost every time I go out. It eliminates the worry that I might have forgotten to do so.

Two: Make A FistLet’s say you set your glasses down on a table.

Rather than simply walk away, close your fist as if you still have your glasses in your hand.

You can combine this technique with saying the object and the location as you walk away.

This physical sensation will help you carry the memory with you. Later, you can think back to your fist and where you made this gesture. This action will help lead you back to the location.

I suggest you squeeze vigorously. Don’t make this a passive action. Put some drive into it.

Also, if you’re leaving one room to go find scissors and don’t want to forget before you reach the kitchen, make a fist. By pretending you’ve got the scissors in your hand before leaving the room, you’ll remember what you were seeking.

Three: Make Multi Sensory AssociationsNext time you put your wallet down, imagine hearing a massive explosion – just as if you’d dropped a bomb.

Let your imagination soar by making it as loud as possible.

Include a visual flash of light. Feel the ground rumble. Think to yourself, my wallet just blew up the kitchen counter.

Add some emotions, like shock at the explosion.

Follow these simple steps and misplacing things will be difficult for you from now on.

Four: Use RhymesWe’ve already talked about using names. But there are more ways we can use language to help us remember objects and their locations.

Let’s say you have difficulties finding important books on your shelves.

Instead of arranging everything alphabetically (which is not a bad idea), you can remember where books are like this:

My important bookie-wookie is next to Stephen King-a-ling.

Silly, right?

That’s exactly the point. It makes it easier to remember where you stuck that book you always keep misplacing.

People ask me all the time, Why do I keep losing things? I even lose my car at the shopping mall!

I would too if I didn’t use memory techniques.

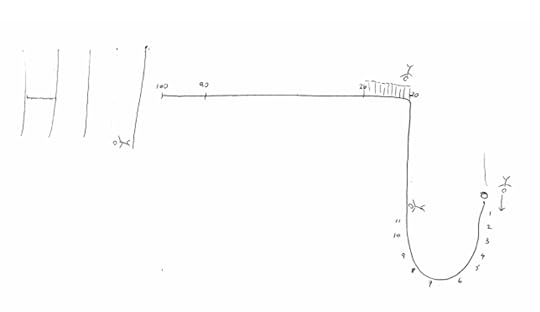

Two of the most powerful for finding your vehicle in parking lots are:

The Major SystemThe Pegword MethodBasically, they help you assign an image to each digit from 0-9 and to every letter of the alphabet.

Then, if you park in B4, you’ll be able to imagine a bee attacking a sailboat. Since “bee” starts with the letter ‘b’ and 4 looks a bit like a sailboat, remembering this location will be a breeze.

Just as imagining your wallet dropping like a bomb needs some multi sensory visualization, you want to enhance this kind of association.

When I use this technique, it’s not the bland idea of a bee attacking a sailboat. It’s a full-scale Hollywood movie with emotions, sounds, intensity and energy.

The trick is to spend a bit of time creating these systems and practicing them. Luckily, they’re easy, fun and provide incredible brain exercise. And when you add the multi sensory aspects, the location of your car leaps instantly to mind.

If you feel a little unusual doing this in the beginning, don’t stress about it. With a small amount of practice, creating associations like this will become second nature.

Six: Turn Your Home Into A Memory PalaceIf you can assign a memorable image to a parking spot, you can do the same thing in your home.

Let’s say you’ve developed your skills with the pegword method. You can then assign a letter and object to each room.

Let’s say you call your bedroom “A” and imagine a grouchy apple lives in it. If you take your watch off in your bedroom, you can think about the grouchy apple complaining about it.

By combining the alphabet with the Memory Palace technique, you will never forget where you placed your items again.

Because the apple is your image for the bedroom, you’ll remember the location. After all, it’s memorably absurd for an apple to be grouchy about you leaving your watch on the bedside table.

If you assign ‘b’ to your living room with Batman, there are all kinds of possible ways to have him interact with your glasses, keys, wallet or anything else you want to remember as you set it down.

If you want to learn more about the Memory Palace technique, check out this free course:

There are many more ways to use your home to remember information. I hope you’ll check it out.

These Tips Will Prevent You From Saying, “I Always Lose Things”You now know how to use associations to remember where you placed important objects.

The benefits of removing this problem from your life include:

Saved timeReduced stressImproved memoryThe more you practice these techniques, the stronger your memory will become.

Of course, the standard advice about reducing clutter and creating reminders for yourself still has its place.

But because life can get incredibly hectic, your best bet is to become a “Warrior of the Mind,” and make using association a habit.

As always, the best app on the planet is the software you’re running in your head. Please use it, and if I can help you further in any way, just post below and I’ll get back to you a.s.a.p.

Don’t worry – I haven’t missed (or lost) a comment yet! 🙂

May 19, 2021

What Is Prospective Memory? Everything You Need to Know

[image error]Prospective memory is fascinating. Your entire future relies on it working well.

Why?

Well, let me ask you this:

How do you know that in the future you will remember to remember?

To test our ability to remember the need to remember in the future, researchers S. L. Penningroth and W.D. Scott asked a bunch of university students the following question:

“Imagine that your friend has asked you to make a call tomorrow morning to provide a personal recommendation for a full-time job. You must wait until morning to call because that is when the potential employer will be in the office.”

As Beatrice G. Kuhlmann discusses in the excellent book of essays, Prospective Memory, different students listed different strategies. To remind themselves of this future event, they might remember to make the call by:

Mentally rehearsing the call Using an app for notificationLeaving a note where they would be sure to see itSetting a specific time to make the callThese are all examples of metacognition that helps us remember future intentions. Without both intention and metacognition, we are all at risk of some serious prospective memory failure.

That’s why being able to remember to do things and perform actions in the future is so critical.

Let’s look more at this important type of memory and make sure you understand its importance, how to preserve it and even how to make it better. That way you can stop missing so many appointments and forgetting to do the things that matter.

Prospective memory is literally defined by remembering to do things in the future. This means that it is primarily linked to tasks.

Attending a classGoing to an appointmentCompleting a task at work on timeTaking medicationRemembering to pack a lunchThe Two Main Prospective Memory TasksThere are at least two kinds of tasks that prospective memory influences:

Time-based tasksEvent-based tasksTaking medicine at a particular time of day is a time-based task because it happens at a specific time. Another example would be baking. If you warm the oven for 10 minutes before putting the cookies inside, that task is time-based and your prospective memory operates in accordance. You can also think about these kinds of tasks in relation to procedural memory.

By contrast, event-based tasks involve some kind of cue in your environment.

If you see a grocery store on your way home, this might remind you that someone in your family asked you to pick up some apples or tea. In other words, this kind of prospective memory comes to mind when something you see, hear or feel cues you to think about the task.

Seeing a grocery store can trigger your memory that you need to do some shopping.

How Do Researchers Study Prospective Memory?In order to analyze how people engage in prospective memory tasks, researchers create models. They do this by finding volunteers to participate in research studies that involve time-based or event-based tasks.

For example, S.J. Gilbert devised a study testing how people “offload” their future tasks. By creating a model of how people behave, he noticed an interesting difference in leaving reminders for yourself that you might recognize:

“I might write the details of an appointment on a piece of paper, which reminds me of where I need to go, but only after I have remembered that I need to go somewhere and consulted this record.”

In other words, making a note about an appointment in the future is no guarantee that you will remember to look at the note. You might even be confused by notes that you left for yourself. Thus, the implication of this study is that:

We often need more than written remindersWe need to be very clear about the written reminders we do leave for ourselvesWhat Does A Model Of Prospective Memory Look Like?They’re pretty fascinating, actually!

A typical model of prospective memory shows that there’s a process that is divided into three categories:

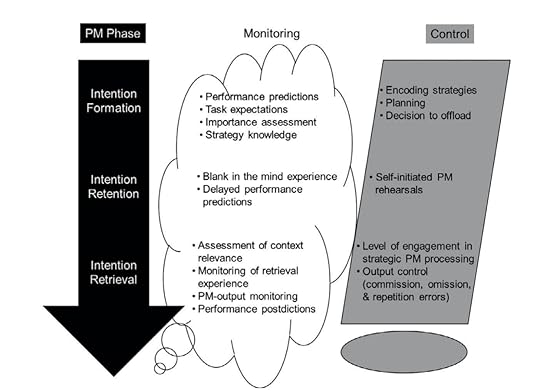

A simple model of prospective memory showing three phases with several steps in each. From the book, Prospective Memory (Current Issues In Memory).

Prospective memory, which involves:Intention formationIntention retentionIntention retrievalMonitoring, which involves:Predictions, “Will I remember this?”Experiencing blanks, “What was it I needed to do?”Assessing your memory for any reminders you might have left, “Didn’t I write the time down?”Control, which involves:Consciously using encoding strategies (like using a Memory Palace)Consciously reminding yourself about the task (rehearsal)Correcting for any errors (checking that an appointment was 4 p.m., not 4:30)Does Prospective Memory Worsen With Age?The answer depends on the nature of the experiment. Some have shown that older individuals do just as well as younger people. Others show that there can be issues, especially in cases where Alzheimer’s is present.

Here’s an example from Dr. Dawn McBride discussing a study that reveals the difference between younger and older individuals:

https://player.vimeo.com/video/529860739

(McBride, D. (Academic). (2016). What is prospective memory? [Video]. SAGE Knowledge.)

“In a study we conducted in my lab a few years ago, we compared prospective memory for older adults, people who are 55 or older, and younger adults, college students.

What we asked them to do was a common everyday task. We gave them a postcard and asked them to mail it back to us after a particular period of time had passed. In other words, a time-based task. Some subjects were asked to mail it the next day. Some, two days later. Some, five days later. All the way up to a month later.

We asked the subjects not to use any reminders. Like, not to put it up on their refrigerator to remind them, not to put it in their calendar, not to set an alarm, anything like that. Because we wanted to know how good their prospective memory was without any of these reminders.

We sent the subjects off, asked them to mail back the postcard without these reminders. And then we compared the performance for the older adults, those who are over 55, and the college-age students. And what we found is that, over time, the longer the period of time was before they were supposed to mail it back, the college students’ performance declined.

[image error]

So if it was the next day, they did pretty well with the task. We got most postcards back on time. But if it was a month later, we got very few of the postcards back for the college students.

The older adults, however, did really well at this task. They in fact, almost all of them, sent the postcard back on time, even if it was a month later.

However, what we found is that, even though we asked them not to use external reminders, the older adults did in fact tend to use external reminders, based on a questionnaire that we sent to them after the study had ended. So in this particular study, we showed that older adults do actually perform prospective memory tasks very well, but they rely a lot on external reminders to do those prospective memory tasks.”

Note: In case you haven’t observed this point for yourself already, the older participants in the study either did not pay attention to the guidelines, or forgot to follow them.

Prospective Memory ExamplesPablo Picasso reportedly said, ““What one does is what counts. Not what one had the intention of doing.”

This is important because examples of prospective memory are really examples of intentions people have for the future. The key difference is whether or not they successfully remembered to do what they intended.

[image error]

Why is this important?

Simple:

The more goals you complete, the better your retrospective memory becomes. In other words, you enjoy going through your past so much more because you can be proud of all that you accomplished.

With that point in mind, here’s a list of examples from prospective memory psychology textbooks:

Setting a New Year’s resolutionJoining a pre-scheduled fitness program at the gymBuying a concert ticket and remembering to attendTaking out the trash in time for collectionPaying a bill on timePre-planning a reaction (if x happens, I will respond with y)Watering plants on a scheduleRemembering a birthday or anniversaryReturn borrowed books to a libraryFollow safety procedures (pilots, ship’s captains, etc.)Can You Improve Your Procedural Memory?Yes. And you do this by improving on what scientists call “implementation intentions.”

As Anna-Lisa Cohen and Jason L. Hicks point out in their book, Prospective Memory: Remembering to Remember, Remembering to Forget, “ implementation intentions can create habit-like behavior.”

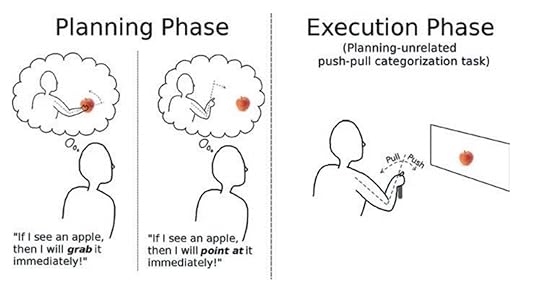

They suggest that it is possible to create plans with an “if-this-then-that” structure broken into two phases:

Planning phaseExecution phase

The planning and execution phases of prospective memory. From the book, Prospective Memory: Remembering to Remember, Remembering to Forget.

Basically, you need to add clarity to what you’re doing to strengthen the link between perception and action. With enough focused attention and repetition, you will be able to practice the habit of being clearer in a way that promotes better procedural memory in the future.

We’ve already seen an example of this above:

Instead of writing cryptic notes to yourself, like “4.p.m.” you want to include as much information as you can: Specific names, dates, locations and the purpose of the reminder.

You can also memorize future events using a “Mnemonic Calendar.”

Memory expert Jim Samuel helps senior citizens remember to take medication by helping them turn their homes into a Memory Palace.

For example, if you have to take a certain medication on Monday, this day of the week can be linked to your kitchen sink. If you imagine a giant moon in the sink and visualize it swallowing that pill, every time you enter the kitchen, you can think about this and it will help you remember:

To check what day it isIf it’s Monday, to take the medicationYou can have these mental reminders all throughout your home. To learn more about this technique, check out:

Remember To Do Things: It’s Life Or DeathAs you’ve seen, prospective memory is pretty clear once you get into the details.

Whether you’re an airline pilot or someone enjoying your retirement, you need to be able to remember future events.

All in all, being able to remember what to do and when to do it is what makes us human. And the quality of our lives really do come down to how we’re able to perform both in the now and in the near and distant future.

Obviously, science is not done studying this form of memory. But it’s pretty clear that intention is the key to improving it and there are some quick wins I’ve shared with you today.

So what do you say? Is your future looking brighter now that you know the ins-and-outs of this form of memory?

May 12, 2021

Anterograde vs Retrograde Amnesia: A Simple Guide

[image error]Amnesia is a tricky term to understand because it is used in so many ways.

For example, it has become popular to talk about “political amnesia” to explain the “crisis of memory” in various parties. Movies and streaming series also often feature characters suffering some form of memory loss and calling it “amnesia.”

But using the term amnesia in these ways muddies the waters of an already complicated topic.

So let’s bring some light to the field of forgetting as we explore retrograde vs anterograde amnesia in full, including some specific case studies from scientific literature.

Anterograde vs Retrograde Amnesia: What’s the Difference?The difference is found in the prefixes.

Something that is anterior is situated in front of another object or event.

“Retro” as many of us know, refers to the past.

Therefore, anterograde amnesia refers to having difficulties forming memories after amnesia sets in.

Retrograde amnesia, on the other hand, refers to experiencing issues with accessing memories before the onset of amnesia.

Let’s dig a bit deeper and look at some specific examples. That way you can truly learn the difference between retrograde and anterograde amnesia.

What Is Anterograde Amnesia?Christopher Nolan’s Memento, released in the year 2000.

According to clinical neuropsychologist Sallie Baxendale, this movie’s representation of anterograde amnesia is fairly accurate. As she explains:

“The film documents the difficulties faced by Leonard, who develops a severe anterograde amnesia after an attack in which his wife is killed. Unlike in most films in this genre, this amnesic character retains his identity, has little retrograde amnesia, and shows several of the severe everyday memory difficulties associated with the disorder. The fragmented, almost mosaic quality to the sequence of scenes in the film also cleverly reflects the ‘perpetual present’ nature of the syndrome.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vS0E...

“Perpetual present” is a key term here because people suffering anterograde amnesia cannot lay down new memories.

Why does this happen?

Traditionally, scientists have thought that anterograde amnesia is likely caused by something interrupting the consolidation of new memories. Here’s how Dr. Michaela Dewar puts it in her contribution to the excellent book, “Cases of Amnesia: Contributions to Understanding Memory and the Brain”:

“During consolidation, new fragile memories become increasingly resistant to disruptions.”

Dr. Dewar’s research at Heriot Watt University’s Memory Lab suggest that more rest can help people suffering from anterograde amnesia.

[image error]Research findings from Dr. Dewar’s Memory Lab project on distinguishing retrograde and anterograde amnesia.

Exactly what it is that interrupts consolidation remains unclear. Dewar suggestions it could be: