Anthony Metivier's Blog, page 17

February 24, 2021

11 Benefits of Critical Thinking That Rapidly Improve Your Life

Can you guess how many benefits of critical thinking you’ll enjoy along your journey of mental mastery?

Can you guess how many benefits of critical thinking you’ll enjoy along your journey of mental mastery?

The number is huge and here’s why:

The value of learning to think critically compounds over time.

In fact, the more you practice, the more positive outcomes you’ll experience.

So let’s dive into these benefits and point out some tips that you probably haven’t applied before.

The best part?

We’ll exercise our critical thinking skills as we go as I demonstrate a few ways I’ve used critical thinking myself.

Why Is Critical Thinking Important?See what I just did there?

I asked a question to demonstrate the first major benefit.

Asking and knowing why something matters helps you:

Place it in contextLearn about its historyUnpack and analyze its partsFor example, we know that human civilization only really starts going when people started to think.

And that probably only became possible because our ancestors discovered how to irrigate land for farming.

Although human history is obviously more complex than that, it’s also pretty simple: If you don’t have to spend all your time hunting and foraging for food, you can rest and think more.

The more you can rest and think, the more you can think about maximizing your free time, which is ultimately what gave rise to the Internet we’re using to communicate with each other now.

This means that more free time and better communication between people make critical thinking so important.

Why?

Because the better you get at thinking critically, the more free time and better communication you will enjoy.

11 Incredible Benefits Of Critical ThinkingThe following list of the benefits you can expect from thinking more critically are in no particular order of importance.

But that doesn’t mean they can’t be ordered. You can benefit a great deal by thinking through which of these benefits you feel are the most important. Use ordering as a means of practicing your objective reasoning skills.

One: Critical Thinking Gives You Practice In Multiple Disciplines

Want to be able to think faster?

Use “mental rotation.”

When I was in university, and even to this day, I used this critical thinking skill.

Here’s how it works:

Let’s say you are given a problem to solve, such as inner city poverty.

It’s a huge benefit when you can look at the problem from several perspectives, rather than just one. For example, you can mentally rotate through:

Political perspectivesPsychological perspectivesBiological perspectivesEthnographic perspectivesHistorical perspectives Economic perspectivesEthical perspectivesEtc.The critical thinking benefits of “rotating” through these perspectives happen because they exercise your thinking skills. As your perspective grows, you can spot more possible options for the next benefit.

Think of “mental rotation” like a moving windmill of possible mental models you can move through while enjoying the benefits of critical thinking.

Two: Avoid Unnecessary ProblemsThe more perspectives you have, the more models you can mentally navigate. These models (like the ones listed above) help you imagine different outcomes.

Essentially, you enable yourself to create multiple versions of the W.R.A.P. technique taught in the training on ars combinatoria, an early critical thinking tool you might want to explore. It’s just one of several critical thinking strategies you’ll want to learn.

Of course, not all problems are avoidable, and it would not be appropriate to think critical thinking will create some kind of friction free paradise.

But although some decisions will always create new issues, you can seriously reduce the negative impact of those decisions in advance simply by thinking things through with the widest variety of mental tools you can find.

Three: Brain ExerciseYou get brain exercise from critical thinking for a few reasons.

When you shift through multiple perspectives, you’ll be promoting cognitive switching. Research shows that this mental movement is the healthy equivalent of walking for your heart and lungs. Only in this case, the benefits are directed at your brain.

In this case, you’ll be getting even more benefits thanks to how critical thinking gets used in conversations. For example, a fit brain is much more likely to use objective reasoning and avoid the traps of subjective reasoning.

Here are more brain exercises I think you’ll enjoy.

Four: Personal Time ExpandsNow, we’ve talked about how critical thinking was used to help entire societies expand their free time. This works at the individual level too.

For example, if you run an online business and want more free time, nothing will help you faster than applying critical thinking skills to how you can release yourself from certain tasks.

If you’re a student, you can learn techniques like interleaving, just one way of several authentic ways to read faster.

But, if you don’t have critical thinking skills to help cut through the rubbish and pseudoscience out there, you could wind up losing time instead of gaining it.

Five: Communication And Your Use Of Language Improves

Conversations become so much more beneficial when you can use multiple forms of critical thinking in real time.

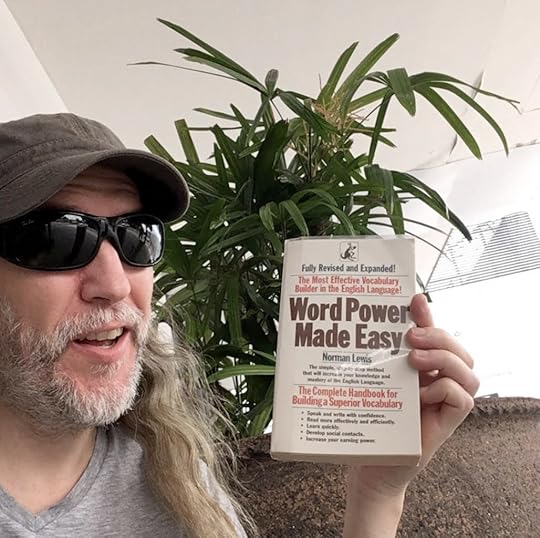

Like any area of skill, you will learn new vocabulary when you study critical thinking.

New words directly lead to improved language abilities.

Plus, you’ll gain a sense of which kinds of words and phrases to use in which contexts.

Linking thinking with better use of language has always been part of the memory tradition we discuss on this blog. It goes back at least as far as 90 BCE where it was codified in Rhetorica ad Herennium.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X3rts...

Six: Scientific Living Improves Health

When you use your mind well, you’ll be able to make much better decisions related to your health.

For one thing, instead of always taking your doctor’s word for it, you’ll learn to understand the math behind their decisions and decide just how much it applies to you.

This relates to the use of language as well. For example, how many people know that “doctor” is the Latin word for “teacher.”

Using critical thinking can help you correctly assess the roles of people in your life, such as knowing that “doctor” means “teacher.”

If you start to think about your own medical professionals in this light and treat them as the starting point for educating yourself, you’ll probably make much better health decisions.

Plus, when you know word origins like this, an important skill for critical thinkers, you’re able to think faster on your feet.

That is very beneficial for our text major set of benefits:

Seven: Catch Yourself In ConversationsHow many times have you found yourself in a loop of self punishment after saying something you regretted?

According to psychoanalysts like Robert Langs and Robert Haskell, we “encode” unconscious ideas in how we speak.

Now, some critics think these thinkers were reaching after hidden meanings that aren’t there. Although it is true that some of the evidence presented by both is questionable, at least in Langs’ case, he was protecting the identities of his clients.

I feel that Langs has compelling ideas and one of the issues he faces is simply that his theory attempts to account for criticisms leveled at it. As a result, there is a history of people going on the attack rather than having a decent conversation about the topic.

And that’s said because if Langs is even remotely correct, we could all stand to reduce a lot of unnecessary problems from our lives by holding our tongues in advance, rather than feeling badly about the innuendo encoded in our speech later.

Eight: Intellectual Honesty IncreasesI give the Langs example because the contemporary world is filled with bad actors willing to criticize theories or ideas they haven’t fully explored or tried.

That leads to intellectual dishonesty and it harms many people.

But if you’re willing to admit that you haven’t looked at something enough to think critically about it, you do everyone a favor. You also save yourself a huge amount of time and energy because you don’t have to backtrack, watch your back or have part of your brain monitoring the environment for threats created by a lack of integrity.

Nine: Critical Thinking Promotes IndependencePeople who fail to acquire the advantages of critical thinking never experience as much independence as they could.

Obviously, we always want to consult others. That need is never going to go out of fashion.

But there are many situations in life where we simply don’t have the luxury of getting a second opinion. And when that happens, we want to be able to rely upon ourselves.

The problem is… what if you can’t remember how to use the tools of critical thinking?

Don’t worry. I’ve got you covered.

Once you can remember the critical thinking tools and perspectives you’d added to your mental toolkit, you can use the same Memory Palace technique to train yourself to use them almost on autopilot.

Ten: Better CareerWho enjoys the best jobs on the market?

The people who can think on their feet and consistently make great decisions.

Not only that, but they’re able to accomplish other lifestyle goals a lot faster because they have great careers.

Think about it. When you have a great job, you’ll enjoy:

Better salaryGold standard health insuranceRetirement packagesCompany perks like travel expenses and a carNicer offices to work inCloser access to higher level colleaguesThe pleasures of contributing more, etc.Eleven: Everyone Becomes A Better Citizen Of Planet EarthOf course, you don’t have to be (or even want to be) a top level employee or executive manager.

Improved critical thinking benefits everyone. Think of our entire planet as “Team Together” and make sure you bring your best game.

You can enjoy the benefits of contributing to your fellow humans no matter what roles you choose in life.

Merely by learning the importance of critical thinking and applying it in daily life, you will be helping other people.

How Many More Benefits Do You Want?As you can probably tell, there’s a fair amount of crossover between these benefits.

And that means you can expect a lot more than eleven benefits as you practice critical thinking in your daily life.

I know because I taught a fourth year Critical Thinking course for several years as a professor.

I saw many students experience all of the benefits on this page and more.

If I were to sum it up in one word, it would be that they flourished.

This means that they were more than happy. They enjoyed an abundance of positive rewards, and all because they took a bit of time to learn how to think better.

So what do you say? Are you ready to start practicing your thinking skills? Let me know in the comments section and together we can contribute so much to the world.

February 17, 2021

Objective vs. Subjective Reasoning: Everything You Need to Know

Have you ever made a decision, only to realize you could have been more objective and less emotional?

Have you ever made a decision, only to realize you could have been more objective and less emotional?

It happens to people all the time, and that’s usually because they don’t have decision parameters.

In other words, they don’t have systems of thought that help them use objective reasoning.

That’s important, because it’s definitely not something that happens on autopilot.

This point is also important:

It’s not that subjective reasoning or emotional reasoning is bad. Objective reasoning is not some kind of superhero force of good battling the dark forces of subjectivity.

But without placing our subjective experiences and ideas within the context of as much pure objectivity as possible, we rob ourselves of important opportunity.

What opportunity?

The opportunity to harness the power of context. Moreover, we want to enjoy the fullest possible field of context so that we can successfully weigh all of our options before making critical decisions.

What Is Objective Reason? A Working DefinitionObjective reason goes beyond decision-making and your overall critical thinking strategy skill stack. Being able to reason objectively also helps you understand history, psychology and many other topics much better.

And when you can reason through any topic using multiple layers of reasoning, you’ll remember more as you understand the contexts at play much better.

When defining objectivity, we need to look at standards of thinking. In other words, we want our definition to include:

LogicImpartiality and balancePractical mattersTheoretical mattersTime for deliberationPsychological biases that interfere with objectivity

Objective reasoning involves a balancing act of several elements, including logic, data and awareness of many cognitive biases.

In a phrase, objective reason is a mental thought process that requires logical consideration of a situation or topic that is informed of the possibility for distortion from subjective bias.

For example, people using objective reasoning will be:

Highly self-aware of their mindsAware of a variety of tools for analysisInformed about the role of science and data in making good decisionsWilling to take time for research and deliberationWhat Is Subjective Reasoning?People using subjective reasoning tend to either avoid or not know about the importance of objective tools, theories and the need for scientific data.

Data is a key part of learning to reach reasonable conclusions.

Instead, they rely upon their personal opinions, experiences and tastes. If they think outside of their personal context, they will tend to refer only to other people they know.

For example, they will say, “I don’t know anyone who has had this experience,” and allow that small, personal data set influence their decisions.

By contrast, an objective reasoner will say, “Although I don’t know anyone who has this experience, I’ll do some research to find out what scientific studies exist so I can expand my awareness.”

This form of reasoning is objective because it looks to the external world for information rather than relying solely on the individual’s first-person experience and ideas.

Is Objectivity Even Possible?Good question.

The answer is yes.

However, we need to realize that the tools of science and data appear in the human brain’s of individuals. This creates the fact that each and every person experiences everything subjectively.

This fact does not mean that we as individuals cannot use objective reasoning to access facts that are true regardless of our subjective opinions and experiences.

We just need to be aware of the fact that we all experience cognitive biases. In fact, we need them to survive.

We just need to be aware of the fact that we all experience cognitive biases. In fact, we need them to survive.

For example, humans are biased for evolutionary reasons critical to our survival. But in the modern world, researchers like Daniel Khaneman have shown many ways we can avoid some of the traps of subjective reasoning and become objective where it is useful to do so.

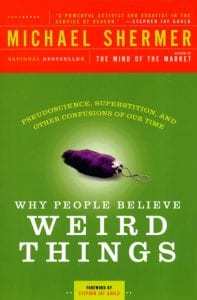

In addition to learning about cognitive biases, it is useful to also study game theory books and texts on critical thinking. Why People Believe Weird Things by Michael Shermer is one of my favorite critical thinking books of all time. You Are Not So Smart is a close second.

How To Be Objective In Your DecisionsNow that we have a working definition of objective reasoning, let’s dive into some tips that will help you use objectivity to make better decisions.

I’ll share even more of my favorite books along the way.

One: Keep Learning About The Differences Between Objective and Subjective ReasoningNow that you’re here, the journey has just begun. And it’s very important you keep studying this topic.

Here’s why:

It’s nice to learn about things, but that doesn’t mean you will completely understand them, let alone remember the key points.

To really benefit from developing objectivity in ways that will benefit you for life, find books that will teach you:

The history of reasoningCultural/geographical differences that influence reasoning (like proxemics)Philosophical issuesPsychological issuesDecision making books related to specific topics (business, family, health, etc)It’s a great journey and the more you learn about this topic, the more you can learn about it as your brain makes deeper connections over time.

Two: Practice Objective Reasoning FrequentlyOn top of educating yourself, the key to making objective decisions well is practice.

The great thing about many objective reasoning tools is how they can be deployed almost anywhere.

Practice involves a few components:

The decision to startOngoing analysis of your thought processesLearning to identify and separate your subjective reasoning impulsesCreating distance and delay between your subjective ideas before making decisionsAnalyzing your own subjectivityPerforming needed deliberation and/or researchStress-testing your conclusions by imagining various outcomesMaking the decision and following up with “postmortem” analysisI realize this sounds like a lot of steps, but in many situations, it takes just a short while to go through the process.

In fact, during earlier periods of history, people frequently used a mental tool called ars combinatoria to help them with critical decision making.

Three: Use Writing

Writing is a key tool of reasoning.

They say that the pen is mightier than the sword. It seems to help us think better too.

There are a number of ways to use writing to help you make objective decisions. For example, you can:

List the pros/cons of a decisionCreate a to-do list for people you can consultBrainstorm some research resources to search throughMind map a series of possible outcomes after making a decisionEmail yourself a written version of your thought-processesFour: Discuss Frequently With A Variety Of PeopleMany people say that you are the average of your five closest friends.

I’m sure there’s some truth to this statement, but I wouldn’t rely on it.

Instead, try to have conversations with as many people as you can, of all ages and all stations of life.

Frequent discussion with people from all walks of life stimulates more reasoning abilities.

This is important because you’ll build your pool of perspectives based on lived experience.

And because there will be a large number of positive and negative experiences, you’ll have a stronger “radar” for what might be better for you. Plus, you’ll have a better sense of what kinds of decisions to avoid.

Remember O.T.E. as one of the most powerful resources you can have: Other People’s Experience.

Five: Talk To YourselfEckhart Tolle does a great job of pointing out how we drive ourselves insane with inner dialogue in The Power of Now.

However, that doesn’t mean all dialogue is bad.

Just as writing and speaking with others helps you gain an objective set of perspectives, you can also benefit a great deal by using your inner monologue.

Asking yourself targeted questions leads to better decisions.

I personally like to ask a lot of “if?” questions. For example:

If I make this decision, what will be gained?If I don’t make this decision, what will be lost?You can also ask questions that help determine how you are behaving around a situation. For example:

Am I making this decision in order to win? Am I making this decision in order to avoid a loss?Sometimes when you frame things in this way, you’ll notice that you may well be trying to avoid a loss, only to notice that the loss is quite small compared to what you could gain.

But without asking yourself such questions, you’ll never know.

Six: Schedule Critical Thinking Sessions

Scheduling time for thinking is key to developing your reasoning skills.

If you want to get sharp at using objective reasoning to make better decisions, you need to practice.

Why wait until you’re forced to make a decision to use your skills?

Every day, you have the opportunity to set aside some time to journal and go over the decisions you face now and in the future.

For example, I like to journal frequently during morning walks. I find a bench and spend 20-30 minutes going over the decisions I’ve either already made or need to make in writing.

Using a journal to contextualize my subjective reasoning and arrive at objective conclusions has helped me make many better decisions in life.

There are many ways to journal during these sessions. You can:

Use pros vs cons listsDescribe possible outcomesCreate to-do lists for completing research and due diligence projectsMind mapBrainstormTest motivations and rationalesThe important thing is to create the time and space for deep reflection.

Seven: Create Clarity Around Your Motives and IntentionsWe’ve all heard the advice that you need to “know your why.”

However, this statement is a bit misleading and will potentially weaken you.

Is “knowing your why” as important as people make it out to be?

Here’s what I mean:

Is just one “why” really enough?

If you’re making any kind of serious decision, you probably want to have at least five reasons why you’re doing something.

Not only that, but try this alternative reasoning exercise:

List out at least as many reasons “why not.” By completing this step, you create a set of counterarguments that can help you avoid decisions that may prove destructive.

Another way to get great clarity around decisions in an objective way is to use the W.R.A.P. model taught in Decisive by Chip and Dan Heath:

Widen Your OptionsReality testAttain distancePrepare to fail

The W.R.A.P. formula is easily remembered and incredibly powerful for elevated decision-making.

This easily remembered formula is very useful for avoiding errors and generating reliable ideas and possible paths to solutions you likely wouldn’t find in any other way.

Eight: Create BenchmarksOnce you have your “why” in order and have applied W.R.A.P. it’s important to set benchmarks.

These are specific milestones on the way towards your goal. They matter because many goals take a long time to reach and need to be broken down into smaller tasks.

Benchmarks also help you make decisions along the way, so it’s useful to schedule in regular periods of review so you can pivot or augment a certain process when and where needed.

Nine: Create Metrics For MeasurementAs you make decisions and execute on them, you’ll want to have a means of knowing whether or not you were successful.

It’s often said that you can’t manage what you don’t measure, but I think we need to go a step further.

It’s important to measure results in order to reveal clues for attaining more progress in the future.

We need to become aware of the benefits and potential cons of measurement. For example, we can wind up getting so involved in gathering and analyzing data that we wind up in collector’s fallacy.

So as useful as metrics certainly are for testing the validity of the decisions we’ve made, it’s important to cultivate and maintain an awareness of the potential traps in data. This is one of the core points of The Tyranny of Metrics, which anyone interested in objective thinking would do well to read.

Ten: Explore Other Kinds Of Objective ThinkingIn addition to the W.R.A.P. formula, referring to other thinking models is one of my favorite things to do.

For example, the Triz principles have many useful processes that can get you thinking in multiple ways.

Although something like Triz applies to design and engineering, it will still be beneficial. Thinking through such principles, you expand your perspective and can look at your area of expertise with greater objectivity through another lens.

Eleven: Revisit Your Assumptions Frequently

Again, objectivity is something that you experience from within your subjective mind.

This means that no matter how objective you may think you’ve become, your objectivity can still go stale or become corrupted.

One great way to ensure you keep sharp is to develop a regular rereading strategy.

We also change as we age, so it only makes sense to revisit our thinking, ideally by going through the same sources that formed our thought processes in the first place..

Plus, the world is always transforming too.

How To Remember The Steps Involved In Objective ReasoningNow, you might have noticed the nuance involved in developing reasoning skills that will last for life.

But the good news is that you can remember everything quickly.

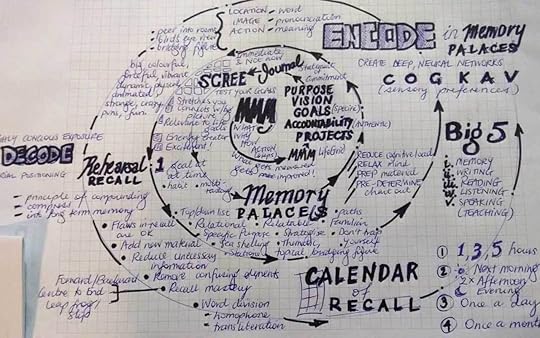

To do that, I recommend learning the Memory Palace technique.

With it, you can take something like the W.R.A.P. model and rapidly remember everything.

You can also create a mnemonic calendar to help you remember to show up and practice the skills we’ve talked about today, like journaling.

Anyone Can Develop, Maintain And Improve Their Objective ThinkingIdentifying your cognitive biases and learning about logical fallacies are admirable learning projects.

It’s just important to understand that the task is never done.

To be truly objective, you not only need to make sure you nurture yourself with multiple viewpoints and learn to be a solid researcher.

You need to continually revisit the process in order to compensate for change.

Your subjectivity won’t go away either, so it’s important to develop the ability to contextualize it amongst the multiple factors that go into being an individual with a sense of self.

Above all, practice making decisions with these tools frequently. Analyze the results of the decisions and allow the data to help guide future choices you make.

None of this should be a chore. Quite the opposite!

Once you have the steps involved honed into habits, it’s all fun, rewarding and helps you live as a better citizen of planet earth.

It’s a win-win for everyone involved.

February 10, 2021

How to Retain Information Quickly: 11 Surprisingly Powerful Tips

If you want to know how to retain information quickly, we can boil the process down to one simple term:

If you want to know how to retain information quickly, we can boil the process down to one simple term:

Strategic repetition.

Now, I realize you’ve come to this blog about memory techniques to get rid of repetition.

I’m sorry. That’s not how it works.

We always need to repeat what we want to remember. In fact, why remember something at all if you don’t need to repeat it?

The key differences with strategic repetition vs. rote repetition are these. Strategic repetition is always:

FunCreativeSkills boostingScientifically provenEven if some repetition will always be necessary for learning, it doesn’t have to be painful. And you often won’t have to repeat nearly as much if you get it right.

So if learning how to retain knowledge in ways that are engaging and stimulating strikes you as a good thing, stick around. On this page, we’re taking a deep dive into ways to retain information that you’re going to love.

Why Can’t I Retain Information? The Surprising TruthIt’s not IQ.

It’s not genes.

It’s not laziness.

The reason why most people can’t retain information is that they simply haven’t trained themselves to do it.

We can take it a step further:

People who can’t learn quickly and recall information on demand not only fail to use memory techniques. They haven’t trained their procedural memory so that they use them almost on autopilot.

You cannot “mind read” books. Use proper study and memory improvement techniques instead.

You see, anyone can learn about memory techniques. But without practicing them consistently enough so they become second nature, all that information is just data.

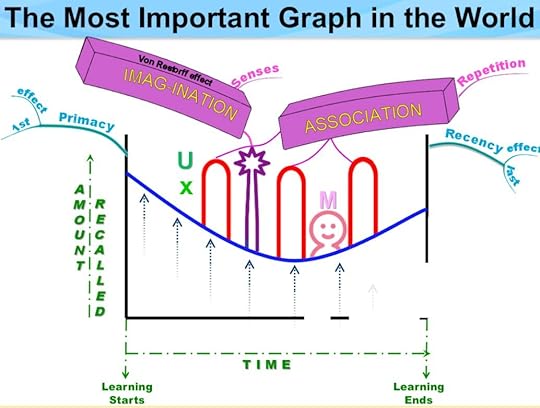

The science here is very simple. We’re basically looking at four kinds of brain processes that you just need to link together:

Encoding information strategically using elaborative encodingDecoding information strategically using active recallSerial positioning with the primacy effect and recency effectsHabit formation so that you start using the strategies automaticallyWe’ll pick up each of these scientific matters in greater detail as we go along. With each tip I’ll share, you’ll discover simple ways to harness the power of each principle.

How to Retain Information Quickly: 11 Proven Tips1: Use Exaggerated AssociationsThe fancy, scientific term for using exaggerated association is “elaborative encoding.”

But you might be wondering… what is an association?

Good question. It’s one of the most powerful mnemonic devices you can use.

Basically, you’re going to look at the target information and find something you can connect to it.

For example, if you need to memorize someone’s name, you’ll look at the first couple of letters. When I met someone with the complex name Gangador Dianand, I just thought about a “gang” first.

Next, I associated that sound with a rap band known to dress as gang members. Then I had them bang on a door.

Using a rap band as a mnemonic device while studying helps you retain information in a fun and engaging way.

That’s the association part. The elaborative encoding part is when you imagine those gang members larger than life and hear the sound of that banging extremely loud. (In your imagination, of course.)

It’s this process of exaggerating the association that makes it so memorable. And that’s what helps with the next tip.

2: Use a Memory PalaceWhen you want to retain info, you need to revisit it.

And after exaggerating an association, the best way to rapidly remember something is to know where you stored it in your memory.

Enter the Memory Palace.

This special mnemonic device is just a mental recreation of a building you’re familiar with and can easily bring to mind.

Here’s an example:

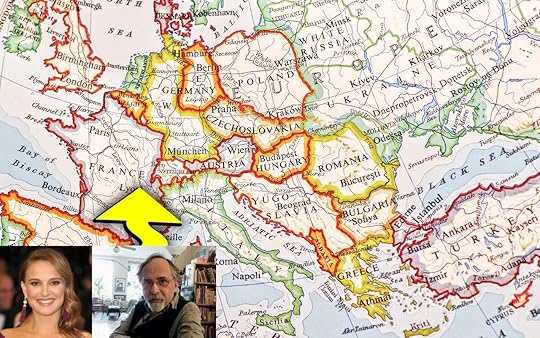

Let’s say you need to memorize some details on a map. If you use Natalie Portman and Art Spiegelman to memorize that Spain and Portugal share a border.

First, you exaggerate an interaction between them. Then you place that association in a room.

Later, to practice what memory neuroscientists like Boris Konrad call “active recall,” you revisit that area in the room and simply ask yourself:

What was happening there?

If you’ve made the association exaggerated enough, your two characters should come to mind and the letters in their names should trigger the target information.

3: Test Yourself StrategicallyIn order to properly benefit from active recall, it’s important that you test yourself.

Unfortunately, a lot of people cheat. They try recalling the information for a second or two, and then give up, exposing themselves to the answer.

That’s called rote repetition. It’s painful, boring and rarely helps with retaining information. You want to use the best possible mnemonic strategies instead.

However, if you have a journal or piece of paper in front of you and the target information is nowhere in sight, cheating is impossible.

Then, when you write out what you memorized using exaggerated association, you get the benefits of active recall.

Even if you make mistakes, you’ll still train your memory to work better. Over time, you’ll get stronger and stronger.

A lot of people “force” themselves to get through one book at a time.

I have a PhD, two MAs and a BA and I can tell you this:

I never do this.

Instead, I take many breaks while reading or taking courses and strategically “interleave” my study material.

This term means that you take breaks often and switch things up. By reading more than one book at a time, you switch from a focused state to the “diffuse mode,” which gives your brain space to remember more.

The research on this goes back at least as far as Karl Duncker who wrote a book about the psychology of productive thinking back in 1935.

More recently, Barbara Oakley has featured contemporary data that substantiates these findings in her famous course, Learning How to Learn.

(Dr. Oakley’s course is also a printed guide and one of the 3 best speed reading books in the world.)

5: Use Proper Reading TechniquesI just mentioned speed reading, but be careful. There’s a lot of garbage you’ll come across in that world.

For example, most of what you’ll read about reducing subvocalization is a farce. Worse, skimming vs scanning strategies are usually poorly understood.

The broad strokes of learning how to read faster boil down to this:

Have goals, missions and systems that help you frame and stick with a focused reading programLearn to use “priming”Extract information strategically (see How to Memorize a Textbook)Use memory techniques to recall the informationMake sure you test yourself using the active recall strategy discussed above (without cheating)6: Improve Your Reading Comprehension SkillsThe first way to understand better is to change your definition of comprehension.

Many people get frustrated and toss their hands up in the air the instant they don’t understand something.

This is an incorrect approach because we read challenging material so that we might understand better. Without challenge, there is no growth.

Instead, learn the best reading comprehension strategies and practice them consistently. For example, I used to look up on charts and grafts and give up on them completely.

By redrawing charts and grafts, you not only improve memory retention, but also comprehension.

Now, I draw them with my own hand to understand them better. This step is essential because not only do I understand them better. I also remember more.

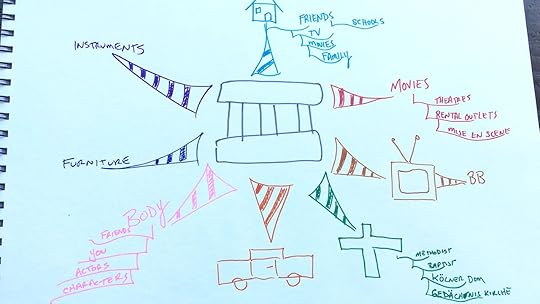

7: Mind MapMind mapping helps you retain information, especially when you revisit your mind maps strategically.

For example, Phil Chambers has given the excellent suggestion that you revisit each mind map at least ten times. Leave a Roman Numeral each time you do so you can remember where you are at in the revisiting sequence.

But… what is mind mapping? Put simply, it’s a graphical means of simplifying key ideas using colors, images and keywords.

Let’s say you want to memorize words in a foreign language. A mind map is a great way to do it. I rapidly retained information about cooking in German, for example:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3I7h9...

Here are more mind map examples you can model.

Mind mapping works as one of the best ways to retain information if you optimize it for that purpose. So I suggest using the Phil Chambers tip I just shared to make that happen.

Mind mapping is an incredible wait to retain more information quickly.

8: Write SummariesWe know that we need active recall to remember quicker and with greater longevity. But we also need to percolate information and make connections.

Writing summaries is one of the best ways to do that. And it doesn’t have to take long.

I suggest keeping a notebook just for summaries of your reading. Commit at least half a page for each book you read and pour out what you remembered in at least 2-5 sentences.

With a small amount of practice, this incredibly simple habit will be the portal to remembering a lot more, much faster. And the best part is that it helps with making connections between different books you read as well.

9: Discuss with othersAs with summarization, a great way to practice active recall is to speak with others about what you’re reading.

Frankly, I’m puzzled by why people would read anything they weren’t going to have conversations about. But it happens.

If you’re having trouble remembering what you read, join discussion forums. Go to meetup groups. Or just run past the ideas from what you’re reading with friends.

Frequent discussion is key if you want to absorb more information and maintain it in your memory.

If you really can’t find others to converse with, speak the key points out loud, either to a pet or to yourself in the shower. The point is to verbalize what you’ve read in your own words. This helps you remember much faster and without a ton of repetition.

10: Meditate Your Way To Better MemoryIt might seem like meditating is far flung from improving your memory.

However, many studies show just how profound meditation is for concentration and focus. Others show how people of many different ages experience improved recall from just four short meditation sessions per week.

Add yoga to the mix for more scientific proof that these traditions prove the best way to retain information without having to learn a bunch of memory techniques.

11: Study Your Personal Rhythms To Maximize ThemI know a guy who used to beat himself up for not being a morning person.

In When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing, Daniel Pink reveals the conclusions from over 700 studies.

It turns out that only 15% of the population performs well during the morning.

Finding your best time of day is highly personal. Explore with a spirit of experimentation.

This means that a huge percentage of people would learn better at different times of day, including later in the evening. In fact, some people remember far more when they study before bed.

How do you find out?

Experiment and track your results.

If you’re willing to keep a journal for a few weeks, you can work out your optimal times for learning and choose them.

Of course, there’s a catch. (Isn’t there always?)

Your best times of day can and probably will change as you age or as factors around you evolve.

This means you’ll want to keep testing and journaling while being willing to pivot throughout your life.

The Ultimate Tip For Retaining InformationAnother word for the willingness to pivot is “flexibility.”

Flexibility is the key to improving memory retention.

When you combine all the tips I’ve shared with you today, your memory is going to be incredibly flexible. And it will always trend towards higher and higher levels of improvement, even as you age.

Since most of us want to be lifelong learners, this should be an issue.

Keep practicing the approaches I’ve shared on this page. The more you explore, the more you’ll discover even more interesting and powerful ways to make learning easier and fun.

After all, the more you can remember, the more interesting and fun things become. And the more you learn, the more you can learn. That’s thanks to the power of connection, which is truly the most rewarding memory technique we’ve got.

So what do you say? Are you excited to get out there and learn more using enhanced memory abilities?

February 2, 2021

How to Think Faster And Avoid 9 Mistakes You Don’t Know You’re Making

When someone asks you a question, how long does it take to come up with an answer?

When someone asks you a question, how long does it take to come up with an answer?

Depending on the situation, your answer might range from “pretty fast” to “way too long!” If you’re like many of my readers, you would like to learn how to think faster.

Today, we’ll stress test the idea of thinking faster with good old Ulysses Everett McGill from the Coen brothers movie O Brother, Where Art Thou? — otherwise known as Dapper Dan.

Dapper Dan thinks he’s sharp. Thinks on his feet. Gets him and his fellow escaped convicts out of trouble… right?

Not so fast! As much as Dapper Dan might believe himself to be a quick thinker, he’s just not as smart as he thinks. Or as smart as he wants everyone else to believe.

Here’s one of the big problems with the desire to think faster: a lot of people want to have faster thinking because they’re concerned about how they look to others. They’re not so worried about accuracy of thinking — they just want to “think fast.”

So instead of going down the Dapper Dan road of quick (but mistaken) thinking, let’s look at how to process information faster AND more accurately.

Here’s what this post will cover:

Why Do You Want to Think Faster?WRAP Your Way to Faster Thinking9 Factors That Slow ThinkingThink Fast! 4 Ways to Improve Your SpeedQuestions to Ask for Faster Thinking9 Tips to Help You Think FasterBook RecommendationsHow to Be a Quick ThinkerReady to learn how to think faster? Let’s get started.

One of the very first questions you should ask yourself is, “Why?”

Knowing your “why” is important, as is knowing your “why not.”

Are you interested in accuracy, or are you motivated by the Dapper Dan approach? The problem with the latter is that it tends to lead you into trouble.

Even if you know the movie O Brother Where Art Thou? you might not know it’s an adaptation of The Odyssey. Looking back at the ancient Greek epic poem, you’ll notice that Ulysses wasn’t that intelligent of a fellow, but boy could he talk the talk.

Ulysses seduced people into thinking he was a lot smarter than he was in reality, and it got him into a lot of trouble (including needing to take a trip to the underworld to try to get himself out of trouble).

One of the important things we learn from The Odyssey is how to make better decisions by not being like Ulysses. We learn how not to “Dapper Dan” our way to bliss and pretend we’re smart.

Instead, we can learn how to think faster in a legitimate way.

So after you decide whether you want speed (Dapper Dan and Ulysses) or accuracy (the Magnetic Memory approach), list out why you want to think faster.

Do you want to look better to others? Or do you have tangible performance needs, like:

Time limits on your examsHigh demands of your sports teamA decision-based professionRather than worrying about what someone else thinks about the grades you get, focus more on getting good grades later on. A good grade’s function is to qualify for more opportunities to study for additional qualifications (if that’s what you want).

It’s the opportunity to learn more and become progressively smarter over time.

Let’s quickly look at our other examples. If you’re able to think fast on the field, you perform better. And if you’re in a decision-based profession – like a doctor or lawyer – you want to be able to think faster on your feet and think accurately.

The vital part is combining and following those avenues of connection to create stable landing pads in the future. It’s not about the speed — it’s about the landing and how hard or soft it is based on the integrity of the thoughts you’ve compiled along the way.

Now you know why you want to think faster, let’s take a look at a model of decision-making that can help you get there.

Rather than the Dapper Dan approach to thinking, I prefer to think slower, more thoroughly, and W.R.A.P.

But what does W.R.A.P. mean? Earlier this year, I read the book Decisive by Chip and Dan Heath, on Olly Richards’ recommendation.

In Decisive, the authors talk about how to make better decisions, faster and more accurately. In their model, W.R.A.P. stands for:

Widen your optionsReality testAttain distancePrepare to failEver since I read the book, I’ve been using the W.R.A.P. formula for everything I do in my life. I think I’ve been good at a version of that throughout my life, but once I memorized it in one of my memory palaces, I’ve been using it ever since.

Next, let’s look at some of the factors that might be holding you back.

You’ve decided you want to think faster and more accurately. But what if hidden factors are standing in your way?

Let’s break down nine things that might hold you back from quick thinking.

1. Lack of PreparationOne of the factors that slows down thinking is not understanding how to prime.

But what is priming? In a nutshell, it’s a phenomenon where you respond differently to a stimulus based on how you experienced that stimulus previously. The stimuli are often at least conceptually related.

I listened to a presentation by Damien Patterson when he talked about this amazing way he used to pass exams in school. Then he went on to immediately denigrate his approach by saying, “this isn’t the most scholarly way of doing things.”

I went up to him during a break in his presentation and had a quick conversation with him. I told him he should congratulate himself for doing what speed reading experts call priming.

I made him aware that it was a major industry that teaches people how to read faster — and that’s why he got top grades instead of the more diligent students.

Those other students were fumbling around and not using proper learning skills. They didn’t have the thoroughness of accelerated learning techniques to get their studying done right the first time.

When people don’t prepare properly and invest in accelerated learning techniques (like priming), it slows down their ability to learn. And even for the people who do, another factor that slows their thinking – and the value they get out of the material – is that they aren’t thorough about taking the course.

2. An Overflowing CalendarHow many people do you know who schedule time just to think?

The answer is probably none (or not many). But this is one of the essential factors that will help you think faster.

Let me ask another question: have you had your thinking time today?

This is not a hypothetical question. Have you literally checked off the box on your to-do list that says, “Yes, I did my thinking time.”?

If not, this is a problem. If you want to speed up your thinking – really accelerate it – schedule some thinking time.

At the end of the day, if you’re not making time to think, you’re not going to be able to practice it.

3. Substance AbuseMuch like the engine of a vehicle, the human body is not made to run on junk.

Smoking, drinking, and other types of substance use and abuse will severely slow your thinking. By keeping your body clean and efficient, it’s able to use the fuel you give it.

For example, if you drink, you make the liver work harder to process out the alcohol. And if you smoke, it’s like clogging up the air filters in your car’s engine.

Instead, keep your machine running clean.

4. Mental and Physical InjuriesSimilarly, other kinds of injuries also impact your ability to think faster.

Back at the beginning of 2020, I hurt my shoulder. It took me a while to get back to the gym, and while I was working through the injury it impacted my thinking speed.

Harvard Health shared findings showing that “moderate-intensity exercise can help improve your thinking and memory in just six months.” There are both direct and indirect impacts: physiological changes as well as indirect action on the brain itself.

Both physical injury and brain injury can slow thinking. When I developed bursitis in my shoulder, I noticed a dramatic reduction in my memory capacity. I did a podcast interview and made a mistake in one of my memory demonstrations.

Now, this might not seem like a big deal to some of you, but I very rarely make mistakes when it comes to memory. I’m sure it came from the injury because I was very slow and foggy at the time.

Once I could get through physical therapy and get back to the gym, I felt so much sharper. It was like night and day.

5. Behavioral Health IssuesDepression is also a significant contributor to delayed thinking.

Many people who suffer from depression report symptoms of “brain fog” as part of their experience. This cognitive dysfunction can mess with your thinking speed and your reaction time, memory, and executive functioning.

But it’s not just depression that can be an issue. Medications can also slow your thinking, as can normal aging.

6. Poor NutritionThink back to the car analogy we used earlier. Proper nutrition is like giving your vehicle the right type of fuel so it can run smoothly.

When you consume too much sugar, dairy, wheat, and other allergens, it’s terrible for your brain and your speed of thinking.

No one diet will work for everyone, so part of your research into how to think faster will involve trying out elimination diets, rotation diets, and just generally experimenting to see what type of foods make you feel (and perform) your best.

I personally cleaned up my dietary act. I got rid of the booze, wheat, sugar, dairy… and my life changed. My brain got so much sharper. So much faster. And my memory improved, too.

I know we can’t make everyone do the same, but I’ll spend the rest of my life trying to convince you why it’s so important.

7. A Lacking LexiconThis one might surprise you: many people can’t think faster because they don’t have a large enough vocabulary.

When I interviewed Jesse Villalobos – a Magnetic Memory student – on my podcast, he basically said he loves that I use big words because it helps with his thinking.

Coming back to the idea of speed reading, there’s new research debunking it. Studies show that the only way to read faster is to have a more extensive vocabulary and significant knowledge of the field.

I dig deeper into the idea in this post about speed reading.

8. An Excess of EdutainmentA lot of people ask me, “Wheres the meat?”

But what does M.E.A.T. mean? Here’s how it breaks down:

MeaninglessEdutainmentAbsurdlyThrivingIt seems to be thriving a lot more on the internet. Instead of aiming to deepen their knowledge on a subject, people think, “Oh, I just want to look for short videos that are all cut up and spread across a couple of hours, so I don’t have to focus or concentrate or engage with the knowledge.”

Don’t be one of those people.

9. Digital AmnesiaI think the kingpin of all of these factors is digital amnesia.

I can’t tell you how often viewers will tell me they wish I made shorter YouTube videos. But if they took a second to look around, there are plenty of shorter videos on the Magnetic Memory Method YouTube channel.

They’re already showing signs of digital amnesia because if they can’t find short videos from me, then there’s something going on with their field of perception. They’re looking on devices that hide half the content.

And this is not how intelligent people go about studying things. You need the largest possible screen so you have the biggest field of perception possible — this is how to eliminate digital amnesia.

The smaller your field of perception, the less room you have for the seeds of detail that grow into knowledge.

Here’s where the Dapper Dan effect comes back in: “I look cool because I have my tiny little device.”

My advice? Get away from the influence of this small device as much as you can. The convenience is killing so many people and ruining their brains. It’s also destroying their ability to see information in context.

It’s Drama Theory 101.

The shorter the content you consume, the more often you have to “turn on the engine.” If you constantly stop and start the engine of content, you end up with cognitive drain.

But what can you do instead? Train yourself to sit and pay attention! Grab your pen and paper, and go through our notetaking training:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U64aw...

One of the biggest challenges we face in our quest to think faster is the accumulation of the nine factors above.

So instead of letting them slow down your thinking, let’s look at what you can do instead.

We’ll get more into how to incorporate the W.R.A.P. approach to faster thinking, but first, let’s tackle an important way to make sure everything you’re learning sticks.

1. Implement ImmediatelyThe first thing to do as you’re learning how to think quicker is to speed up your implementation.

One easy way to do this? Immediately after you read this post, put all of the recommended books into your online cart at your favorite book retailer and hit submit.

Why? Because you’ll follow the speed of implementation rule — every minute that goes by where you don’t take action, it gets less and less likely you ever will.

This will guarantee you never think as fast as you want because you’ll never get to the next stage. Instead, speed of implementation is a principle for thinking faster because it helps you make decisions as quickly as you can.

And my strong recommendation is to only read in physical form, especially books that contain any kind of information of substance.

For example, if you see a recommendation from a reliable source telling you what to do to fix a problem, don’t overthink it. Get your priorities straight, and then follow the advice within 5 minutes of getting it.

Then, when the book arrives, read the whole thing right away.

2. Get S.M.A.R.T.E.R.Earlier in this post, I mentioned my friend Damien Patterson. He believes in L.U.C.K. — which comes from one of his books.

LearnUsingCorrectKnowledgeAnd by using this correct knowledge, we get S.M.A.R.T.E.R.

SeriousMatureAbsolutelyReadyToEmbraceRealityThe reality is, 6-minute video clips are not going to help you think faster. Instead, they train you to think within a small field — and you cannot expect to think faster if you reduce the field in which thinking happens.

You have to expose yourself to longer forms of content to see “thinking out loud” demonstrated and think along with it.

I get frustrated with so-called education “experts” who praise the “snippetization” of content because it gets more people through to the end of courses. But who cares how much content you get through if it’s eroding your ability to think coherently and consistently across time?

In the real world, you need to demonstrate and capitalize on your ability to focus and concentrate.

If not, reality will smack you, and you’ll hit the ground so hard you don’t know what hit you. Your brain is rotting every minute. We’re all dying. It’s just a fact of being alive, and recognizing that fact is part of having good critical thinking strategies. And you can accelerate the death of your brain by constantly exposing it to snippets of content.

Or you can increase your attention span by giving your brain longer content to focus on! You know which of those approaches I recommend.

3. Exercise Your BrainTo accomplish this increased attention span, you need brain exercise.

One way to get brain exercise is by thinking as correctly as possible — to do the best you can in the moment. Do it regularly, frequently, and in a way that my mentor Tony Buzan would.

He says, “follow the rules and the rules will set you free.”

To me, what it means to be free is to study Frequently with Relevant information that improves your life in a spirit of Experimentation and Entertainment.

That’s where memory techniques come in. Practice frequently with relevant information that isn’t compressed and squished into 6-minute snippets. Find longer content that allows you to think out loud — all in the spirit of implementation (and in an entertaining way).

4. Set Aside “Thinking Time”No matter what condition you face – be it trauma to the brain or body – thinking must be practiced.

But we all know how busy life can be. How do you set aside time to think, with all the other things you have going on?

Let’s take a look at a few different approaches.

Digital FastingYou have to actually set time aside, not just think about it or promise to do it. And one great approach for setting aside time to think is to do a digital fast.

There are two kinds of digital fasting:

1. Walkabout Digital Fasting

For this walkabout, you will leave your house with no device whatsoever. Maybe you take a small journal to write in. But the most important thing is to physically separate yourself from technology.

You might go to a cafe or your favorite park. Choose somewhere that you can do nothing but think. You can also choose to bring along a physical book to read during your fast.

You might consider what to think about on your digital fast, or you can allow yourself time to think about other things as well.

The most important thing is to set aside time for U.S.S.R., or Uninterrupted Silent Sustained Reflection.

2. Creating Digital Borders

I used to avoid Instagram completely. But I finally figured out a way to enjoy the platform without getting trapped in it. Here’s how. (You can learn more about this approach in Nir Eyal’s book Indistractable.)

I open Instagram one time per day, or less often. I have a time limit set (there are apps and phone settings that will limit the amount of time you can spend, and I recommend using them) and don’t go beyond it.

I curate my feed so I only see posts about language learning, philosophy from the stoics, and other knowledge-based content.

I go in, I fart around, post what I want to post, and then leave for the day. And the dopamine spike I get from using the platform is more significant than if I was always in there refreshing.

It’s a bigger payoff because I’ve earned it.

This is a weaker form of digital fasting than totally avoiding digital content, but it can help ease you in.

JournalingI love journaling because it’s a fun way to digital fast.

I really like Yanik Silver’s Cosmic Journal. It’s a beautiful art object that involves randomness exercises within a structure.

Rather than getting your dose of randomness from digital sources, you can get it in a way that’s compelling and directs your thoughts in different ways.

And even if you don’t choose a specific guided journaling practice, just spending time with your thoughts and writing them down is also excellent.

Mind MappingAnother technique I highly recommend is Tony Buzan’s Radiant Thinking.

I’m still a student of mind mapping myself, but radiant thinking looks like this:

It radiates out of a central image and also radiates internally — and arrows point around from different topics.

Mind mapping is a way to train yourself to think faster, but you need to set time aside to do it. That’s why mind mapping is such a great way to get in your digital fasting time. It’s a win-win.

This past year, I’ve done so much mind mapping that people might think I’m a little weird. I go out with these giant pieces of paper and a big stack of colored pencils. And I don’t care what people think because I’m not Dapper Dan-ing myself.

Instead, I’m focused on just the outcome, not confusing activity with accomplishing. Just focusing purely on how activity leads to accomplishment, and making sure those activities lead to accomplishment.

Feynman TechniqueAnother way to think faster is to learn the Feynman Technique.

This video shows how to apply an advanced version of the technique:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D_JJc...

You need to craft the best possible approach that makes sure your activity leads to accomplishment. You want to avoid the Dapper Dan problem and the confusion of activity-as-achievement.

Now that you have these four ideas in your head let’s look at how you can create a system that helps you ask better questions.

As you get deeper into your quest for learning how to process information faster, you’ll want some heavy-duty techniques.

The following will help you create a little system in your head that enables you to ask better contextual questions.

Contextual AwarenessFrom the time we are young, we’re taught to ask the 5 Ws (and 1 H):

WhoWhatWhereWhenWhyHowAs you learn how to think faster, you should always have these contextual questions in your mind. There’s a little bit more finesse with the “who” part, but some of the others are relatively simple.

Let’s break down two examples, using “what” and “when.”

What?Ask the following questions:

What is it?When was it created?What is its size?What are its dimensions?What are its parameters?What function does it have?Where was it created?When?We don’t just want to ask “When?” but we want to ask “When” in terms of “What is the actual history by which our understanding of it was built?”

So you don’t want just to say, “Well, they built this particular device in 1812.” Instead, you want to go much deeper — you want to think about the story that tells how we know that history.

For example, let’s take the Industrial Revolution.

First, we need to know when it was generally said to come into existence. But we also need to know what the prevailing tendencies were before its inception that enabled it to thrive? What’s the genealogy?

This would also include the key players. If you want to examine the development of schools, you need to look at education for the previous 100 years.

By incorporating the 5 Ws (and 1 H) as you read, as you have discussions, and as you build up your ability to think faster, the questions will help you finesse out what matters.

This will help you ask the best possible questions to think better and faster. It’s not about the conclusion. It’s about the quality of the questions.

Next, let’s examine the other kind of awareness you want to practice.

Benefit AwarenessThis type of awareness is like “Who?” plus.

When you’re talking about who created something or who said something, ask yourself, “To what benefit?”

Who gets the benefit? Whom does this serve?

As Michel Foucault stated, the definition of power is the ability to conduct the conduct of others. Or, similarly, William S. Burroughs said, very brilliantly, that control seeks to control control.

When you seek the truth, take a moment to check if someone fought long and hard to make that thing true for their benefit. This is a problem amongst scientists because they sometimes base conclusions upon who benefits — but it’s not a problem with science.

Science doesn’t have these problems because science is a tool. It’s the collection of evidence that either confirms or denies a hypothesis. And it helps us make better hypotheses so we can better confirm or deny our ideas about things.

You always want to understand that many people can’t embrace reality because they’re not smart enough yet. This is why it’s vitally important to be S.M.A.R.T.E.R. (Serious Mature and Ready To Embrace Reality).

Benefit awareness will help you cut through the noise and think faster.

And with enough awareness, you can have the best of both worlds. You can have useful philosophical thinking tools and avoid your own cognitive biases.

If you’re stuck in Dapper Dan mode, worried about how people perceive you, then it will be more challenging. But if you’ve got the Dapper Dan problem in check, you’re already ahead of the game.

If you need more help, I put together a special audio presentation called “How to Think” that you should enjoy.

Finally, let’s look at nine different recommendations that will help you with quick thinking.

Before we dive in, a word to the wise: using just one of these tips will help you learn how to be a quick thinker, but you’ll get even more out of this post if you start to combine them.

Which one(s) will you choose?

1. Start a long-term thinking projectThe first tip is to have both a long-term project and a memory vision statement. Not sure how that vision statement should look? Here’s a video that will help:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MFz31...

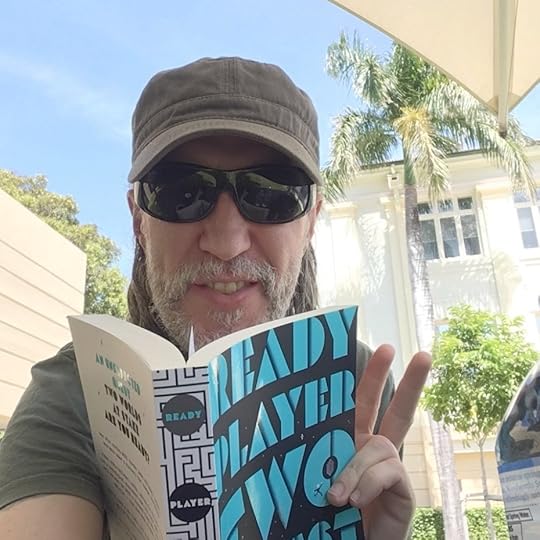

My current long-term project is to understand Hermeticism and memory tradition. I’ve been reading many books as part of the project, including Frances Yates’ book Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition.

For your long-term project, I recommend no fewer than 10 or 15 books on a particular subject.

These learning projects help with thinking faster because the bigger your field of vision and understanding is, the more the seeds of knowledge have room to grow.

To take action on this tip, watch the video above, and create your own learning vision statement.

The next tip helps you both think out loud and experience thought in action.

Online discussion groups are okay (especially right now), but when it’s safe again, go and meet other people in the real world. You’ll see thinking out loud demonstrated to you and observe your own thinking out loud in the context of the people hearing you.

Coming back to the idea of the short 6-minute videos, you’ll get a small portion of the organic action (where soundwaves manipulate the physical structures of your inner ear) but it’s just not the same as being together with people.

Sitting together and discussing, picking up interrupted conversations, it’s all part of the extended thinking that you must practice to think faster.

I try to be a part of a discussion group once a week, and I notice that my thinking is sharper and my mind is more vivid when I do. It has a lot to do with the chemicals created when our brains are with other brains.

To take action on this tip, find an in-person or online discussion group around your topic of choice.

3. Meditate every dayMeditation is a great way to think faster, especially if you memorize a text and make it part of your meditation. What text you choose is up to you.

I also meditate in silence, but my preference is to meditate by reciting texts (especially verses in Sanskrit).

This is very powerful because your meditation allows you to concentrate for an extended time and in a way that produces semantic and echoic material. The muscle memory in your mouth is now linked together with the production of thought.

Instead of fighting against ideas, allow them. I spent a decade fighting my thoughts, and then I learned how to sit just to sit — it’s so much better to let the ideas that come up just flow.

I’ll often meditate with a journal or a piece of paper. That way, when a thought arises, I can write it down and then let it go.

And I also find that you get much more focus at the beginning of meditating on a particular text. After a while, a text’s focus power tends to wear out a bit.

To combat this, you can either pick up new material or recite the text in a different order each time. When you rotate your texts, everything gets primacy and recency in the serial positioning and helps them not wear out as fast.

To take action on this tip, choose a single short text to recite during daily meditation.

You want to track your dreams. But why?

You’ll focus on whether you can trigger greater awareness of the present moment by remembering your dreams. When you remember your dreams with more accuracy, depth, and volume, it exercises your memory.

You want to be able to 1) remember your dreams, and then 2) increase the depth, duration, and volume of recall, which triggers lucid wakefulness.

As you begin to practice recalling your dreams in a dedicated manner, you’ll start to realize that the distinction between lucid dreaming and dream recall may be suspect. And you may begin to become more aware of when you’re daydreaming.

Being in a fantasy is being in a fantasy, whether you’re awake or asleep.

But is there a difference between sleep dreaming and wakeful dreaming? The distinction is that our wake-time fantasies tend to be a lot more about the past we think happened, an alternate version of the present, or something about the future.

If you start to track your dreams and associate them with your dreams scientifically, you’ll want to learn proper associative thinking with dreaming. You can also begin to examine your dreams to see if and how anxieties may manifest in your dreams.

To take action on this tip, keep a journal beside your bed and make it a point to write down every dream you remember as soon as you wake up.

5. Incorporate diffusionAnother great way to think faster is just to let things go or let them percolate.

Here are some of my favorite approaches to practicing diffusion:

Go for a walkPractice digital fastingTake cold and hot showersApply your skills in other areasTake a philosophy courseWrite fictionCold showers are a great tool to increase your discipline. And by switching over to using your skills differently, you can give your brain a break. If you write a lot about non-fiction topics, take a break by switching over to fiction. Change up your mode.

In all these cases, thinking speeds up because you’re practicing thinking in different ways.

I highly recommend reading Alex Pang’s book Rest, where some of these ideas came from.

To take action on this tip, pick one of the tasks above and practice diffusion independently.

Another tip for thinking faster is to be aware of your body. Charisma on Command has a great YouTube video about how to think 10x faster under pressure that I suggest you watch.

That video includes one great tip about how to send a signal to your body so things slow down and calm down so you can think.

When a lot of people get stressed, they start to clamp up. But this just causes your brain to get paralyzed — if you can relax instead, it will help you think faster (and better).

To take action on this tip, pay attention the next time you get stressed. Do you get tense? If so, take a deep breath and see if you can relax instead.

7. Avoid analysis paralysisThis post has been a fun way to learn how to think better… think, think, think, think. But there’s a trap we need to learn how to avoid.

You don’t want to get into analysis paralysis. That’s what happens when you overthink something and mentally rotate it one thousand ways and never take action.

So how do you get out of analysis paralysis? The first step is to acknowledge the issue, revisit W.R.A.P., and then segment your decisions.

Have you widened your options too much? Have you reality tested for too long? Have you attained too much distance? Do you need to get closer?

And if you find yourself overthinking your Memory Palaces, here’s a video about how to fix it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_RJZx...

To take action on this tip, give yourself a deadline to make whatever decision is in front of you.

8. Just get startedThis tip is sometimes easier said than done. But you have more time than you think — because many people treat time incorrectly. They make it a problem when it could be the solution.

You accrete value over time when you practice thinking (and carve out the time to do so). The value comes when you’re consistent.

To take action on this tip, think F.R.E.E. (frequent practice, relevant thoughts, with experimentation and entertainment).

9. Create the Rhizomatic EffectFinally, use memory techniques to create what’s called the Rhizomatic Effect.

Rhizomes are the roots that run deep and interconnect plants of a similar species. Ideas and memories can be thought of in the same way: interconnected and self-replicating.

When you use everything you learned here today, you will end up with aha moments that just happen. “Aha! This connects with that. And that connects with that.”

Do you think you could think faster if you could connect things in your memory? You bet! You want your thinking to be decentralized so it can spontaneously come up with great ideas all the time, from all over the place.

That’s what a good memory palace network can do for you if you use one and fill it with good stuff.

To take action on this tip, start to practice all the information included in this post. There’s no instant formula for success, but with consistent practice, you’ll begin to have those aha moments.

As Magnetic Memory Method readers know, no comprehensive post would be complete without a list of some of my favorite books on the topic.

I’ve mentioned each of the books below in this post. Here’s a bit more about each one and why I recommend them as you learn how to think faster.

Decisive — Chip & Dan HeathI mentioned earlier that this book is where I learned the W.R.A.P. model (Widen your options, Reality test, Attain distance, and Prepare to fail).

This book will help you make better, faster, and more accurate decisions. Remember, it’s a model I’ve used ever since I read the book.

As the authors say, “Decisive offers fresh strategies and practical tools enabling us to make better choices. Because the right decision, at the right moment, can make all the difference.”

Indistractable — Nir EyalIf you would like to know more about controlling your attention and choosing the things that are going on in your life, get yourself a copy of this book.

It’s a quick and fun read, as well as being science-based. It even has a cool device in the back that I highly recommend.

The author asks, “In an age of ever-increasing demands on our attention, how do we get the best from technology without letting it get the best of us?”

I also interviewed Nir for the podcast, where we discussed how to create an indistractable life (and techno-panic-free focus). The interview is a masterclass in how to remove distractions.

Decoding Your Dreams — Robert Langs, MDI spent a lot of time with the author of this book and read a substantial percentage of the books he wrote.

This book talks about dream interpretation in a way that’s not commonly discussed. Rather than a giant index of “what it means when you dream about falling off a cliff,” it gives you a means of testing why you respond to your dreams in the way you do.

This book teaches that, “Dreams — once you learn how to interpret them — are actually an extraordinarily reliable commentary on the way you live your life… you can make sense of the inner truth concealed in your dreams.”

The Victorious Mind — Anthony MetivierI would be remiss not to mention my book that covers how to stay focused. The Victorious Mind helps you learn to free your mind and master your memory.

The book blends detailed step-by-step instructions with scientifically proven practices, including how to craft and use your own Memory Palace to help you think quicker.

If you want to learn how to think faster and dig deeper into what we covered today, this book will set you along your way.

Ready to think faster, today and every day?

With the information you learned today, you can avoid the Dapper Dan trap and think fast (and accurately). Rather than flailing around and using flashy tricks to get yourself out of trouble, you can think on your feet and do what’s best for you and your memory.

You know why you want to think faster, how to avoid the nine factors that slow down your thinking, four ways to improve your thinking speed, as well as the nine tips we just covered.

So what’s next?

Now it’s time to put what you learned into action. You can’t do everything at once, but practice the speed of implementation rule and put at least one thing into use right now.

And if you want to learn more about how to think faster, pick up your copy of The Victorious Mind and permanently kick Dapper Dan mentality to the curb.

January 28, 2021

What Is Ars Combinatoria? A Detailed Example Using A Memory Wheel

Ars combinatoria is a mental technique that helps with both memory and decision making. The term means the art or technique of combination and is very powerful.

Ars combinatoria is a mental technique that helps with both memory and decision making. The term means the art or technique of combination and is very powerful.

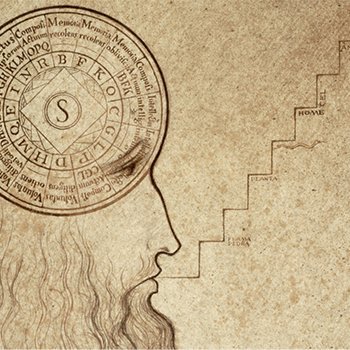

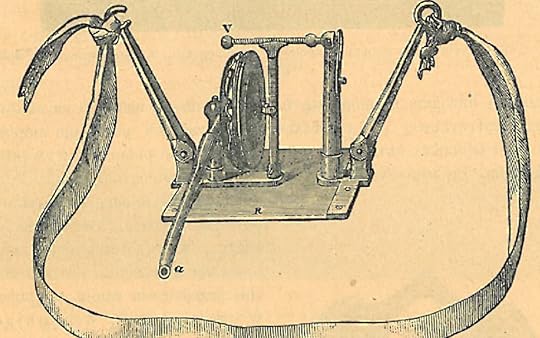

Sometimes called a “thinking machine,” here’s briefly how it works:

You compress larger ideas down into individual letters. These letters are then either referred to purely mentally. Or, as you’ll see, they can be placed on a “memory wheel.”

For example, the letter B might help you compress the word and concept of beneficence. There may be other letters related to B that unpack other large ideas, and the user may need to follow a logical order. Everything depends on the users goals.

To make this technique as clear as possible, including its uses for decision-making, I’ll share a very simple example on this page using a contemporary thought strategy known as W.R.A.P.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0cYDm...

Ars Combinatoria: A Short HistoryThe technique likely originates with Ramon Llull, a philosopher who lived between 1232 and 1316.

Ramon Llull

Its influence is strongly felt and most usefully expounded by the Renaissance memory master, Giordano Bruno.

Note: Sometimes people mistake Bruno’s astronomical diagrams for memory wheels. It’s important to understand that his attempt to help us visualize an infinite universe based on finite solar systems does not necessarily relate to his theories of knowledge and memory.

Although using this critical thinking strategy may involve a “memory wheel,” using one is not strictly necessary. You could also use a traditional Memory Palace.

The point of using such a technique?

Ars combinatoria provides rapid mental access to pre-existing mental content you can use to either follow a process or arrive at optimized conclusions.

Two example memory wheels that use ars combinatoria.

How to Apply The Ars Combinatoria to Your Learning JourneyThe first step is to have a goal.

For example, when Ramon Llull devised the technique, he wanted instant access to information needed to persuade people to adopt Christianity. Since books were heavy and difficult to transport and people are skeptical, it was important to deliver reasonable arguments based on deep familiarity with doctrine.

And Llull didn’t just want this rapid access for himself. He wanted a specific pattern of reasoning to flourish in the minds of many evangelists. That way, his convictions stood a stronger chance of spreading far and wide.

In Giordano Bruno’s case, Bruno adopts some of the ideas from Llullian ars combinatoria, but applies them more to what we might now call “self help” concepts.

Perhaps the best book to read for clarity on this is Bruno’s The Seal of Seals. You can listen these conversations with translator Scott Gosnell for more information:

Scott Gosnell Talks About Giordano Bruno

Scott Gosnell On Giordano Bruno And The Composition Of Images