Anthony Metivier's Blog, page 13

January 13, 2022

How Memory Works: A Guide Anyone Can Understand

Memory works like breathing and blinking:

Memory works like breathing and blinking:

You can control it to a certain extent and it operates entirely on autopilot, whether you’re paying attention to it or not.

How do we know?

Think about your home.

Did you have to work hard to learn the layout?

Probably not. You probably learned it automatically.

The alphabet, on the other hand, required exercises and repetition over weeks. Your teachers guided the process.

As an adult, you need to guide the memory process yourself when you want to learn new information.

Given that memory is both an automatic process and a tool we can use deliberately, how exactly does it work?

The answer is fascinating and comes with many clues that will help you improve it.

Let’s dig in.

How Does Human Memory Work? The 3 Main ProcessesScientists think that memory is built from processes that work together. These processes are:

EncodingStoringRetrievingEncodingEncoding takes place during and after information enters your brain through the senses.

Take the example of learning your home layout. In Human Spatial Memory: Remembering Where, the authors present a number of theories. One of them is that our brains remember spatial layouts by determining which objects are on top of other objects.

This approach suggests that you remember the location of the kitchen because the countertops and the stop stand on top of its floor. The tub is on top of the bathroom floor, etc. The brain then uses what is called its “coordinate system” to encode the information.

One theory of memory says that our brains track surfaces and what objects or on top of other objects in order to remember our environments.

When it comes to learning information like a language, we can deeply integrate with the process by using one of several forms of active recall.

How are Memories Stored In The Brain?In terms of storage, scientists think our spatial information may reside in the parietal lobe. They’ve reached this conclusion because damage to this area of the brain disturbs our spatial awareness.

Storage is a big topic because it’s not clear that information ever really stays put in the brain.

On the contrary, scientists have shown that information we’ve memorized moves around over time. Memory expert Dr. Gary Small likens this movement to how families might travel from homes around the world to gather at a Thanksgiving dinner.

RetrievalDr. Small’s analogy suggests that our memories are actually split apart and keep moving around in the brain. Then, when we retrieve the memories, they move to a single location so we can perceive them as something that feels whole.

And when our recall does not feel whole and complete, that’s because some parts of the memories did not make it to the party.

Here’s more detail on recall and retrieval with more details on where memories are stored.

How Are Memories Formed?People tend to think that long term memories take time to form.

However, scientists know this not to be the case. Not only can certain protein synthesis formations rapidly form long term memories, we also experience flashbulb memory.

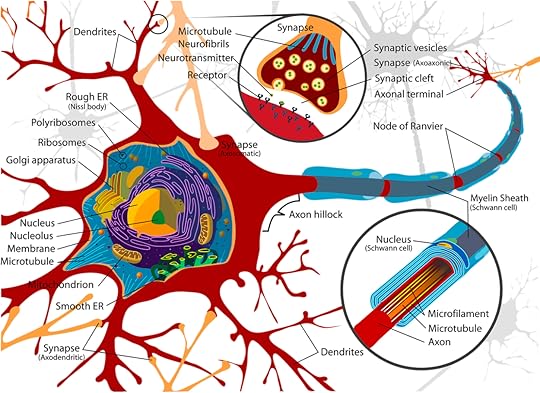

Either way, the direct answer to how memories form is neurochemical. It is literally the collaboration of existing brain structures working together to “connect.”

You can even see the process take place with your own eyes as neurons find one another and connect:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CJ3d1...

As memories connect, myelin wraps around the connections. The strength of any given memory appears related to the robustness of the connection itself, the strength of the myelin sheath and the length of the dendritic spines on the neurons.

Although the exact process of how memories are formed and stored is still not well-understood, scientist and memory expert David Eagleman claims in The Brain that every healthy brain has room for a zettabyte of information.

Where Are Memories Stored?As mentioned, memories are stored all over the brain. And the exact location changes.

This means that the most direct answer to the question is that our memories are stored in our synapses. They are literally stored in connections.

But there’s another way to think about the question.

Memories aren’t just stored in your brain.

They are stored in the brains of other people.

In books.

Movies.

Recorded music.

Library archives.

Our species has devised alphabets, words and grammars to help us encode knowledge in a variety of mediums. To focus only on the brain is missing the point.

But what remains the same is the focus on our memories being stored in the connections themselves.

As you read this post, you are connecting your brain to mine. My remembered knowledge about memory is flowing into your brain. And if you decide to engage with it deeply, this knowledge will become part of your knowledge-set.

If you don’t, the fact of your individual forgetting does not mean the information isn’t stored somewhere. It will still be right here on this page, located in the memory of multiple computers across the Internet.

We tend to think that memory is stored in our minds. In reality, it is stored in multiple locations and devices, if not in the connections between things themselves.

My suggestion is an example of abstract thinking about memory, and I’m confident that when you reflect on the point, you’ll agree that it’s true.

Ultimately, I think the most interesting type of memory involves new research suggesting that memories are not stored in synapses at all. Rather, they are stored in DNA and RNA.

This is new and emerging research that hasn’t been performed on humans yet, so has to be taken with a grain of salt. But it’s worth keeping an eye out for developments.

The Main Types of MemoryConfused by all the types of memory you find people talking about?

I don’t blame you. There are a ton of them.

Luckily, we can break them down into the three main types of memory. Then there are all the rest.

The biggest three are:

Sensory memoryShort-term memoryLong term memoryAfter that, memory scientists break the categories down into:

Episodic memoryAutobiographical memoryProcedural memoryWorking memorySemantic memoryIconic memoryVisual memoryContext-dependent memoryProspective memoryEchoic memoryImplicit memoryNon-declarative memoryExplicit memoryEidetic memoryIn addition, you’ll find special topics like:

Focused attentionCrystal and fluid intelligenceSynesthesiaHyperphantasiaSerotonin and memoryAmnesiaLong term memory lossStress and memory lossMemory disordersThe myth of photographic memoryConclusion: How to Improve Your Memory

Luckily, you can easily improve your memory.

The first step is to pay attention as much as possible.

Then, you’ll want to learn various techniques. The most important are:

The Memory Palace techniqueThe Major MethodThe Pegword MethodPAO SystemTo place the foundations of these memory improvement skills in your hands, grab this FREE Memory Improvement Kit:

The best part?

Once you have superior memory skills, it’s easy to remember all the different kinds of memory we discussed today.

It’s a real win-win for you and the world. The more we understand about how memory functions and what exactly it is, the more people can better navigate reality and lead more fulfilling lives.

So what do you say? Are you ready to live a life more connected to the information storage and retrieval device alive and well in your head?

December 22, 2021

Why Questioning Everything Is the Smartest Thing You Can Do

Do you want to know why questioning everything is the best policy in life?

Do you want to know why questioning everything is the best policy in life?

It’s because humans are prone to error, including the smartest amongst us.

In fact, there’s a principle called “the curse of knowledge” that highlights this problem.

A popular example of how this plays out in life is in the exchanges between Dr. Watson and Sherlock Holmes.

Holmes often points out how Watson doesn’t see the simplest things simply because he doesn’t question the details enough.

It’s not that Watson isn’t a smart guy. He’s a doctor, after all. But because questioning things is such a small part of his mental activity, he misses both the big picture and the granular details.

As a result, Holmes shines as an incredibly bright individual and Watson seems rather dim, despite his credentials.

If you’d like to learn how to question things with greater frequency so you can observe the world in-depth, stick around.

In this post, we’re diving deep into why you should always question everything and different ways to do it well.

Why Questioning Everything Is Critical to Great ThinkingThe ancient Greeks knew that asking questions was their best bet when it came to critical thinking.

A lot of people associate questioning as a tool introduced by Plato through the Socratic dialogues.

Although it’s true that Plato used the character of Socrates to highlight the use of questions to sharpen our thoughts, inquiry is much older.

The Pre-Socratics, for example, devised what is called Eleatic Philosophy.

Parmenides of Elea, from which Eleatic Philosophy gets its name, is sometimes considered the first of the Greeks to use questions to explore the nature of reality itself.

Here’s the most important point about these philosophers:

They preferred to use logic instead of their direct senses.

And this meant using language in particular ways.

In fact, a lot of their wording boils down to a kind of math though the use of syllogisms that help with thinking logically.

Here’s an example of a typical syllogism:

“All mammals are animals. All elephants are mammals. Therefore, all elephants are animals.”

To test the validity of this statement, the philosophers would use questions that remove their senses.

It might sound silly to us today, but put yourself in their shoes for a moment.

If you were to use purely your sense of touch to assess an elephant, you could conclude that this animal is a reptile based on its leathery skin.

So, before the Greeks developed classification systems, many of which we still use today, they needed to question everything in order to rule out errors that could mislead them.

Another way to look at the questioning process is to understand the difference between abstract thinking and concrete thinking. In each of these types of thinking, you use different kinds of questions to arrive at the truth.

The Dialectic ApproachSticking with the ancient Greeks, let’s look at Plato a little further.

One of Plato’s main contributions is called dialectical thinking.

Through the use of questions, it allows you to reason effectively by producing multiple ways of looking at just about any issue or problem.

It works because you use questions to examine your thoughts and the thoughts of others before, during and after arriving at conclusions.

In other words, the process of questioning never really ends.

This process is the core of the scientific method, in which nothing is ever “proved.” Instead, we use our scientific questions to help us produce evidence that either validates or invalidates our assumptions about the world and reality.

Without being able to ask and answer questions as an ongoing process, truth fizzles up quickly. And this is why Plato’s recording of the dialogues of Socrates is such an astonishing document.

Whether Socrates is right or wrong, what matters is the freedom to debate and keep questioning things.

Although the ancient Greek philosophers are very important, they weren’t alone in urging us to question.

The urge to question everything why as a repetitive practice is found in other ancient texts like the Upanishads.

These texts were influential in forming contemplative traditions like Advaita Vedanta.

In Advaita Vedanta, there is a process called “self enquiry” (Atma vichara).

In it, you use questions to explore reality as it appears to you.

For example, you can ask, “To whom is this experience happening?”

When you try to find the “inner I” or what some psychologists call the “ego” within the frame of your experience, you will probably struggle.

That’s because things like “I” and the notion of having an identity is fundamentally an illusion. It is one we maintain by failing to ask questions. Instead, we simply go with the flow.

Or we avoid questions out of fear, which is one of the messages you find in some religious traditions. For example, in the Book of Job, asking god to explain why suffering exists is strongly frowned upon.

The popularity of such restrictions is a bit puzzling, but a lot of psychoanalysis helps explain. And psychoanalysis itself uses a process of questioning to help people relieve the suffering that not asking questions creates.

How To Start Always Questioning EverythingIf you want to commit to a life of enquiry, bravo. I’m confident you’ll find it very rewarding.

In order to get started, consider the following steps:

One: Decide To Go All In And PlanOne of the biggest problems people face when they take on a new goal is that they’re not fully committed.

That’s just not going to work when it comes to committing everything. And the reason why should be clear:

We’re talking about everything.

So if you want to question just some things, some of the time, reconsider whether or not dialectical thinking is really something for you. It’s not about dabbling.

And because it’s not about dabbling, you’ll want to plan.

For that, let’s move on to the next step.

Two: Study Inquisitive People And Their TraditionsOne of the best ways to learn how to enquire deeply is to study those who have gone before you.

And a reading plan of the classic texts that are based around questioning everything is key. I’ve already mentioned a bunch from the Greek tradition, but here are some other suggestions.

Merely by reading the books and resources on this list, you should find yourself starting to question everything almost on autopilot as your brain starts mimicking the process.

Plato’s Republic Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics Ramana Maharshi’s Be As You Are Berkeley’s Three Dialogues between Hylas and PhilonousHeidegger’s The Question Concerning TechnologyList of unsolved problems in philosophyHoftstadter’s Gödel Escher BachSand Talk by Tyson YunkaportaHarris’ Free WillWeber’s Evolving Beyond ThoughtThe Victorious Mind (my book, building on Dr. Weber’s work)There are many other books to recommend, but these are some of the ones I’ve found most useful for training my mind to ask questions.

Not just any questions, but questions of the highest possible value.

You can apply the study of inquisitive people to any area, including finance. For example, studying the questions asked by investors like Warren Buffet can be incredibly rewarding.

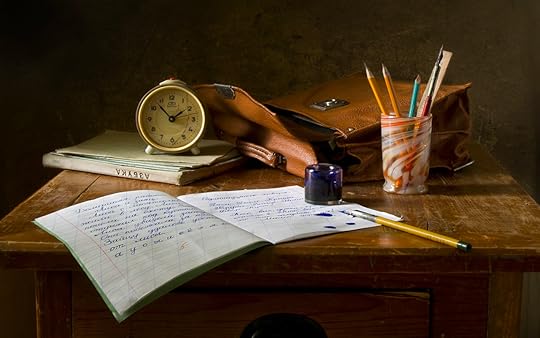

Three: Put Your Questions In WritingWe often resort to questioning things mentally.

However, getting our hands involved is a best practice due to the benefits of haptic memory. This form of memory involves physical touch and belongs broadly to sensory memory, which is readily exercised.

To practice questioning in writing, consider keeping a journal dedicated to this purpose.

Also, note that writing out answers to questions is part of the artistic process. In The Successful Novelist, David Morrell shares how he has used a process of questioning to help him derive the plots of very successful novels. He uses writing to flesh out answers to specific questions that draw out realistic plot points his readers love.

Four: Verbalize Your Questions With OthersJust as we benefit from processing our ideas physically through writing with our hands, processing questions with our mouths is a godsend.

Think about it:

Speech science reveals that at least 100 muscles are involved in speaking aloud.

Now, not everyone has interested parties to speak with, so get this:

You can still exercise all those muscles by asking yourself questions out loud.

I do this often and feel no shame in it. It’s a purposeful verbalization of my questions that not only generates better answers, but sometimes helps me improve the questions themselves.

This happens because I hear how sometimes I limit my wording, or miss the point. I cannot imagine perceiving these deficiencies in any other way.

Five: Review EverythingRe-reading books or re-taking courses is one of my favorite strategies for asking better questions.

In fact, at the time I’m writing this post, one of my projects involves trying to re-read as much of my university syllabi as possible from my first year to 2009 when I completed my Ph.d.

It’s a massive project, and I don’t pretend that I’ll be able to cover everything.

However, I’ve already noticed with the books that I’ve re-read so far that the quality of my questions have improved. They’ve done so by virtue of a kind of guiding meta-question:

These questions now have a powerful pair:

Who am I now as I read them again?What do I feel now?Where am I?What do I conclude now?What are the notable differences between then and now?

Although you might not take your re-reading strategy to the same lengths I am, the benefits of comparing and contrasting your experiences based on these questions is huge. I personally feel that this is one of the most strategic ways to enquire into many aspects of reality at the same time, so hope you’ll give it a try.

Question Everything Within ReasonAlthough I’ve presented questioning everything as a beneficial practice, moderation and discernment are required.

I imagine that you, like me, ultimately want freedom in life. This means that we can’t become a slave to needing to question everything all the time. Frankly, I doubt anyone could, even if they tried, certainly not without making themselves sick.

Rather, enquiry is best as a constant practice. This means that you work on it consistently, a mental strength initiative no different than the physical strength programs we apply to our bodies.

This means that some planning will be useful, and self-monitoring to make sure we aren’t going overboard.

And the best way to do that?

Using questions about how we’re going about questioning things, of course!

If you’d like a simple course that will help you remember to keep questioning yourself within reason, give this Free Memory Improvement Kit a try:

And let me know:

What questions are you going to ask yourself next?

December 15, 2021

How to Find The Main Points in an Article: A Simple Guide

The number one reason students struggle to find the main points in their reading is simple:

The number one reason students struggle to find the main points in their reading is simple:

You are being tested on your ability to figure out what they are and why they’re important.

Teachers worth their salt won’t give you the answers because to do so violates your ability to learn this skill.

Why is this true?

Because all of human progress relies upon unique and innovative solutions to problems.

And knowing how to find the key points in an article is something that is learned by doing.

Plus, content is not king in this regard.

Instead, context is god.

So you not only need to practice identifying what the key points are.

You need to justify in your own words why those points are so important.

Don’t worry, however.

I have tips for you that will help you improve your skills in this area.

Even if giving main points examples is beside the point, I will share some from my own reading.

I’ll teach you how I as a person with two MAs and a PhD earned those degrees by finding what’s important in my topic and justifying my decisions.

Ready to see A+ written all over your report cards and university transcripts?

Let’s get started!

What Is A Main Point?A main point has several aspects to it. For starters, we have:

What the author meantWhat the author actually said

Now, you might think that this is splitting hairs.

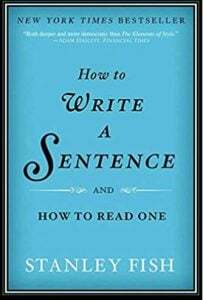

But as Stanley Fish put it, “the world is one thing, words another.”

Fish is the author of How to Write a Sentence: And How to Read One. A huge part of his point is that there’s a difference between what a person actually means and how words can be interpreted in many different ways.

There’s a word for this problem: Polysemy. We face it when “a single word, phrase, or concept has more than one meaning or connotation.”

Because many sentences have this issue, the main idea of a passage almost always requires interpretation in your own words.

And if you want to interpret really well, you need to give evidence to demonstrate why your take on the meaning of the passage is valid.

So we might as well face an uncomfortable truth:

To a certain extent, a main point is what you say it is plus what you can validate through argumentation.

Main Points In The ClassroomThe definition I’ve just given applies to all aspects of life, but might not be what a teacher in a classroom is looking for from you.

It may be that you need to give a specific answer. This is why I say that “context is god.” In order to pass a test or get an A+ on a paper, the right answer might not be in your control no matter how much evidence you provide.

I’ve personally suffered situations several times where in multiple choice exams, the wording of the question made it impossible to give the best possible answer.

That’s why I’m glad that I used to follow a few simple steps:

Read the textbooks thoroughly and answer any section or chapter quizzesTalk to my teachers to make sure I knew exactly what they were looking forGo through sample exams from previous yearsAttend study groups to discuss possible exam questions in advanceOnce in the exam setting, if I could not figure out what answer the person grading the exam considered correct, I took a detour.

I would handwrite on the exam that I could not give an answer in good faith. Then I would write on the back of one of the pages a full explanation of why I thought the question was worded poorly. Finally, I gave the answer in prose that I felt was correct.

Although I cannot advise you to do the same, this strategy saved my skin in several exams. I always passed and did complete most of my degrees with honors, something that would have been impossible if I followed the “rules.”

In my case, my main idea paragraphs (or what I sometimes called “paragrowls”) saved my skin many times.

The Best Way To Identify A Main Point

At the end of the day, the best way to know the main point is to question everything.

Ask yourself:

What is the author trying to tell me?What are the words the author uses?How is the topic introduced and concluded?What do any diagrams or illustrations tell me about the main points?What references to other research does the author make?What do commentators on the author say about the main points made by the author?Can I find where in the book or article those commentators drew their conclusions?

By asking and answering questions like these, in combination with the strategies I’ve shared for how I used to pass exams, you should feel confident that you can find the main points much easier now.

What Are Subpoints?Subpoints are easier to define.

Remember how I said that we need to validate our opinion about what counts as a main point?

Authors of books and articles need to do this too. And subpoints is how they do it.

A subpoint typically involves:

Giving an exampleProviding evidence in order to substantiate a claimParaphrasing another sourceQuoting a sourceAnalyzing a secondary textProviding a variation on a key pointPerforming historical or theoretical analysis on a main pointFor a quick example of a subpoint, just scroll up.

When I mentioned that I’ve passed all my exams so well that I’ve earned the highest degrees you can get at a university, that was a subpoint. It is providing evidence to support the claim that my strategy is valid.

I could actually make the claim even more valid by providing proof that I have a Ph.d., such as by giving you this link to the alumni page of York University’s graduate program in Humanities.

Are subpoints more important than the main points?

In many ways, yes. They are often the evidence that substantiates the main point. Or they provide the nuances or historical background that help explain what makes the main point important.

How to Find the Key Points in an Article in 3 StepsNow that we have defined main ideas and subpoints, let’s talk about some powerful ways to find them.

The following steps do not have to be followed in any particular order, though I do suggest always starting with the first one.

Step One: Know Your GoalAs I mentioned, a teacher or examiner may have a definition of what counts as the main point. I’ve given you some strategies for figuring that out.

All you have to do after determining what counts as a main point in your particular context is to read the books with that definition in mind.

If you’re completing a doctoral dissertation or writing a book like I often do, the burden is a bit heavier. Your goal is to have a research question before you start reading.

Answering this question, and any sub-questions you may have, is your goal.

Step Two: Keep Detailed & Moveable NotesBecause it’s not always possible to know the main idea of a story or scholarly book I’m reading, I take notes on cards.

I shared a detailed tutorial on how I do this in How to Memorize a Textbook.

As I discuss in that post, there are several benefits to taking notes on cards, but one of them is that you can constantly reshape your “deck of notes.”

The more you read, the more your idea of what counts as an important point might change, as will the subpoints you notice.

Keep in mind that subpoints don’t always have to come from the same source. As a former university professor myself, I can tell you that one way to make sure you get an A+ on your essays is to cross-reference several articles.

By doing this as much as possible in your writing and when answering exam questions, you’re demonstrating reflective thinking. This impresses your graders and will later impress hiring managers too.

Step Three: Test For ValidityOne of the best things you can do is test your assumption that a point is as important as it seems.

You can test the validity of what you’ve decided are the most important details in your reading by:

Checking introductions and conclusions again for confirmationLooking through the index for the terms you’ve selectedFollow-up reading online and in other booksAsking your teacher or professor if you’ve understood the reading correctlyTalking with others to see if they’ve reached similar conclusions

Ultimately, having your test, submitted assignment or the things you write yourself graded or scored by others is the ultimate validation. You need either the feedback of your teacher or comments from the court of public opinion to know if you’ve hit paydirt.

And that’s a very good thing. External validation is a huge part of how we grow.

Yes, it takes some courage and sometimes you might get things wrong. Being willing to admit that and then commit to improving in the future is the best response. And so long as you commit to doing that, you cannot lose.

A Final, Powerful Way To Find Main PointsThere’s an ancient technique for finding out what really matters in any given text.

It involves using a Memory Palace.

Basically, you memorize a few details, or entire quotes. Then, you analyze them from within memory.

By doing this, you’re able to consider them in a way that is much deeper than if they are only partially absorbed in your mind.

If you’d like to learn more about this technique, consider going through my Free Memory Improvement Kit:

This approach has helped me many times throughout the years, not only for academic goals, but also personal progress in other areas of life. I’m talking about health, mindfulness and professional matters.

Give it a try, and let me know:

What questions do you still have about identifying the main points in the texts that you’re reading? I love updating posts and answering questions in the comments.

And that’s another strategy you might consider:

Online discussion. It’s a great way to figure out what matters most to yourself and others.

December 8, 2021

Am I Naive? How to Tell (And Fix It)

We are all naive sometimes.

We are all naive sometimes.

And make no mistake:

That can be a very good thing in the right context.

Why?

Because the core of scientific, philosophical and personal progress requires the ability to see the world with fresh eyes.

By the same token, being naive can also be incredibly destructive.

It can force you to miss out on so many of life’s pleasures because it can make you:

Irrational when rationality is neededSkeptical when active participation is requiredEmotionally destructive when only reason can save the dayBut here’s the very good news:

When it comes to learning how to be less naive, the improvement process could not be simpler.

And this post covers how to increase your wisdom in precise terms.

Ready?

Let’s get S.M.A.R.T.E.R together!

(I’ll tell you what the acronym means later. I promise!)

Am I Naive? The Top Seven Signs of a Naive PersonScientists have shown that being naive is essential to our cognitive development as kids. We literally cannot tell the differences between things without allowing curiosity to help us distinguish the difference between things.

For example, as kids we scientifically test the world. We learn to avoid hot surfaces by being naive about what they are and how they harm us.

This means that the number one way to know if someone is being naive is pretty simple.

One: Lack of ExperienceIf you want to know how to stop being naive, ask this simple question every time an opinion floats to your mind:

Do I actually have the experience required to make my opinion valid?

Questioning everything in this way will instantly make you a smarter person. You’ll certainly stick your foot in your mouth much less often.

This is true because intelligent people ask questions – or at least acknowledge that a topic is in question – before making final statements about it.

But naive people?

Not so much. You can often tell by the speed of their answers that they simply lack the background knowledge required to give an intelligent response.

Two: Lack of Self-AwarenessSome people suffer from the Dunning-Kruger effect.

This takes place when a person is not smart enough to know that they aren’t educated in a particular topic area. It’s very destructive, and one need only look at the comments on various social media sites to see how rampant this problem is.

Three: Poor VocabularyDid you know that scientists have warned that the vocabulary of our young people is rapidly shrinking?

This connects to our first point about how experience helps us differentiate different things in the world.

We rarely do this through experience alone. Our language helps us process the experience and deepen it through communication with others.

But if we don’t know the words for objects and experiences, our ability to understand and connect them with other aspects of reality shrinks.

Four: GullibilityHaving a larger vocabulary has been shown to help you read faster, which helps you avoid being easily cheated or deceived. The more you know, the more you can know.

Yet, there are people out there who talk for hours about things like the Mandela Effect with zero evidence that it exists.

Watch out for people who misuse scientific-sounding terminology to take advantage of the gullible.

They don’t realize that other people exploit their lack of scientific literacy.

They do this by showing them ads to sell them products packed with other sensational material. Entire industries direct themselves at consumers with limited mental processing power.

Five: Lack of Critical Thinking SkillsNow, I don’t mean to put only a few people on the spot. Incredibly smart people also display gullibility from time to time.

Desperate health situations, lack of time to think and other situations can cause even people with very high IQ scores to blunder.

However, people with critical thinking abilities often realize their mistakes much quicker. Often, they’re able to reverse course before any significant damage has been done.

They can do this because they’ve had some training in critical thinking, like the kind you can get on this blog. Here are some resources if you’d like to beef up your brain so you can think through important issues faster and make fewer mistakes:

9 Critical Thinking StrategiesAnalytical ThinkingAbstract ThinkingConcrete ThinkingLogical vs. Rational Thinking14 of the Best Critical Thinking BooksSix: Lack of Willingness To ChangeThey say that the only constant is change. But one of the top signs of a naive person is inflexibility.

Nietzsche put it best when he said that asking someone else to change is like asking the entire universe to change. But isn’t that often what naive people do?

As I suggested in my TEDx Talk, which centered on a naive passage of my own life, we know that we can’t change others:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kvtYj...

But we can change ourselves.

So if you want to stop being so naive, make sure to check out the various ways that you can change yourself in the section below.

Seven: You Do Not Put Time Aside For ThinkingBelieve it or not, thinking is not a natural activity. We descend from animals and our autopilot instincts are geared for survival.

This means that thinking not only has to be learned, but in order to keep it sharp, it also has to be practiced.

A sure sign of a person being naive is when they say that they made a “snap decision.” Some people will even brag that they are “impulsive” or like to “rely on intuition.”

True, life sometimes forces us to make choices on the fly. We may have to listen to our gut.

But it’s never ideal and it’s naive to think so. As Chip and Dan Heath point out in their book, Decisive, much research shows that not taking a time to think things through harms us much more than we think.

Yet, societies around the world are so collectively gullible that we valorize impulsive celebrities and spend hours following the trainwrecks of their lives.

Luckily, you can avoid belonging to the herd, so let’s turn our attention to simple ways to get more experience, become more intelligent and enjoy reality at an increasingly mature level.

How to Stop Being Naive in Eight StepsFortunately, there are many ways to reduce gullibility and become an accurate thinker on a quest for constant improvement.

Let’s have a look at some of the best.

Step One: Take Time To Analyze Things ThoroughlySnap decisions are deadly. And once you’re in the habit of making them, it can be hard to change.

However, it actually doesn’t take that long to make intelligent decisions. But you do need to take the time it requires to think things through.

One model I love is the W.R.A.P. technique in Decisive. This approach applies to many situations where you will benefit from thinking things through. It works like this:

Widen your optionsReality testAttain distancePrepare to failTo give you an example, let’s say you hear about repressing your subvocalization from a so-called speed-reading expert.

Before you take this expert at his or her word and plunk down your hard earned cash on their training, you can widen your options by looking up what credible scientists say about this issue.

Then, you can reality test the person’s claims by seeing what they’ve accomplished in life with their approach.

Finally, you can take a break to get some distance between yourself and the topic and let your brain ruminate on autopilot through a process called diffuse thinking.

If you decide to go ahead and invest in the idea after taking time to deliberate, be willing to fail.

By the same token, you should accept that in some areas of self-education, it pays to fail. If you don’t go through a course or two created by charlatans, you risk not sharpening your BS-detection skills, which also requires you to prepare for failure.

In sum, taking time to think in a structured manner is a great way to suffer less from being naive in life.

Step Two: Take Personal ResponsibilityGullible people often avoid seeing how they steered themselves into harm’s way. But that’s an avoidance strategy and one that prevents you from growing.

Even worse, you can wind up trapped in learned helplessness. As researcher Martin Seligman has shown, it’s easy for humans to accept and even come to love the things that hold them back. But it’s also readily possible for anyone to learn to reject the limiting factors in our lives. Studies have shown that feel good dopamine increases when you take actions that increase your mental strength.

In order to become more resilient and learn from your naivety, you need to acknowledge its presence in your life, accept it and then plan to do better.

Getting some time on the calendar to study critical thinking or improve your memory through a program like the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass is a great way to do that.

Step Three: Reduce Screen Time & Mindless ConsumptionThere was a time when people thought that intelligence was fixed. But research that identified what has come to be known as the Flynn Effect showed that in the 20th century, people were in fact getting smarter and smarter in each and every generation.

This trend continued until recently, but now some researchers think that intelligence may be spiralling downwards. They even call this a reversal of the Flynn Effect in some areas of human knowledge and skill.

One explanation for why this downward trend is taking place is digital amnesia. As the Internet moves closer and closer to creating zero latency online environments, people become increasingly hooked to their devices. Indeed, the CEO of Netflix once said that their only competitor is sleep.

By spending more time reading books, even if you’re a slow reader, you’ll give your mind for reflective thinking that fast-paced online environments usually train your brain to avoid. They are designed to keep you clicking without thinking, whereas reading offline is all about connecting with the thoughts of others in a sustained way.

Step Four: Improve Your Vocabulary In More Than One LanguageA lot of people will tell you to travel to give you more life experience. But let’s face it: the beaches and areas of historical interest around the world are packed with as many naive people as your hometown.

A better way to gain world perspective is through language learning. This is because working with languages is what James Hordern calls knowledgeable practice.

The best part is that memorizing vocabulary is fast, easy and fun. I regularly review my copy of Word Power Made Easy to keep my English sharp and read in other languages at least 3-5 times per week.

Step Five: Design Your Own Long Term Learning ProjectsA lot of people randomly pile books into their Amazon shopping cart, or collect suggestions on Goodreads.

But savvy lifelong learners are curators of their knowledge. They may read broadly, but usually within highly concentrated areas of interest for dedicated periods of time.

I took so many courses at university, my brain has been trained to think in terms of semesters.

To this day, I search the Internet not for lists of the best books on a certain topic, but for university syllabi put together by experts. I try to find the biggest and most authoritative textbook on a topic that I can, and then read at least 2-3 of the books it discusses within.

This style of learning allows me to lean on the curation process of experts as I develop my own expertise. Then, when I throw in wildcard discoveries along the way, I automatically read them at a higher level and avoid falling into gullibility because a critical foundation for understanding the topic has already been established.

For any topic I’m studying, I seek to include books from at least these categories:

History of the topicTheory of the topicPractical applications of the topicCritical biographies related to the topicIf you seek the best possible books from each of these categories and spend 3-6 months focused on them and supplementary materials, you won’t be naive about that topic for long.

And stick with your reading plan. Remember: Variety definitely is the spice of life, but the truth in the cliche won’t help if you keep changing disciplines. You can dive deep into topics and connect them a lot better if you spend periods of focused time on fewer topics in more detailed ways.

The best part is that your focus will compound in value because you’ll have learned the meta skills of how to learn and see many more connections thanks to your depth of study.

Step Six: Carry A Notebook EverywhereI can think of few things that have helped me more than carrying a notebook 99.9% of the time.

Although it’s true I use memory techniques, there’s nothing better than working thoughts out on paper and planning with my hands. Plus, having a journal is very helpful for quickly creating Memory Palaces (a powerful tool for remembering things quickly).

Besides planning and keeping track of ideas that emerge, notebooks are great for self-assessment, gratitude journaling and generally expanding your mind.

Step Seven: Practice ObjectivityOne of the hardest things for chronically naive people is to realize that reality exists independent of their thoughts and opinions.

This mistake happens because they are primarily subjective when they would benefit from being objective thinkers.

No doubt about it, being objective is hard.

Fixing this issue starts by understanding that your brain practically forces you to be emotionally invested in everything you see and do. We are driven to navigate the world by the laws and forces of evolution in the same way that gravity holds us fast to the earth.

To become more objective despite having the chips stacked against you, you can make objectivity one of your first learning projects. Study the sciences of psychology, decision making and game theory. Make a concerted effort to become a philosopher.

As part of this project, build a network of people around you who can help stress test your ideas. I suggest joining paid groups rather than free ones. Whereas many of the free ones are filled with low quality posts that will trap you in naive thinking, a solid investment in a discussion group based around deep dives into challenging content will serve you very well.

If you’d like to be part of one of my upcoming groups, consider letting me know!

Step Eight: Know Your Personality TypeOne of my own experiences of being gullible revealed a lot to me about an area I’d never thought about in the context of investing.

For years, I’d been so focused on academic matters and later developing this blog, I had spent almost no time thinking about or studying the different ways I might retire one day.

Because I practice what I preach, I followed a lot of the steps I’ve discussed above. For example, I looked for the foundational books on investing and spent months focused on reading them thoroughly.

I also took courses and spent time with a topic expert to go over my plans.

He said something very interesting to me:

“If you invest in a way that goes against your personality type, you’ll always be miserable.”

I listened deeply to what this expert had to say about personality types when it comes to investing. I journaled about it in my notebook, talked with yet other people and these processes helped me make the right decisions. I know now that I avoided being gullible around a lot of decisions that so-called experts in the field call wise investing, but what actually amounts to uneducated greed.

This particular topic is not very interesting to me, but I’m glad I planned time for it and spoke directly with the experts themselves to help formulate my plans. To make sure you avoid the traps of naivety, I suggest you do the same.

You Don’t Have To Stop Being Naive 100%As I mentioned in the introduction, we benefit from keeping an open mind and cultivating curiosity.

By the same token, we don’t want to keep our minds so open that our brains fall out.

Instead, we want to strive to be what I call S.M.A.R.T.E.R or serious, mature and ready to embrace reality.

This is important because the wisest people amongst us know one thing to be true above all:

None of us know what we don’t know.

In fact, the most intelligent person alive is still shrouded by monumental ignorance. That person must be because the future is not and cannot be known. Plus, so much of the past was never recorded, and mountains of human knowledge that was preserved at one point has since been lost.

But we can learn to think logically and develop problem solving models. It just takes a willingness to get started and keep going.

And it helps to be able to remember the steps that we’ve discussed today. If you’d like help with that, please register for my FREE Memory Improvement Kit.

It will help you rapidly create and use the tools memory experts employ to help them learn faster and remember more.

And when you can do that, you can kiss being destructively naive goodbye. For good.

December 2, 2021

Deliberate Practice: How to Harness Its Power

Are you confused by the amount of advice related to deliberate practice?

Are you confused by the amount of advice related to deliberate practice?

I don’t blame you. After all, there are lots of different kinds of skills that require different kinds of practice.

Not only that, but some people use a different term: dedicated practice. You might also see it called intentional practice. These variations on the term only add more confusion.

But there is an easy way to understand this concept and I’ll give you examples to make everything that goes into proper practice crystal clear.

And if you’re wondering if you need a coach or not in order for deliberate practice to work, we’ll discuss that too.

At the end of the day, deliberate practice will work for you. It’s just a matter of getting the facts straight and learning how to plan.

Since informing yourself correctly is key to practicing well, I’m glad you’re here. Let’s dive in!

What is Deliberate Practice?The term is used often in sports science and is often defined as practicing according to specific steps or instructions.

Dedicated practice is planned, based on small component parts and improvement is meticulously tracked by capturing data. This data is then used for the individual person engaged in the practice to help them further improve by dialing down even deeper on key areas that require improvement.

For example, I study music and take courses online from Scott’s bass lessons. In one of his programs, Scott identifies 9 key areas of deliberate learning for musicians:

TechniqueFingerboard knowledgeAccompaniment skillsTheory and harmonyRepertoire and performanceRhythmic developmentChordal skillsSoloing and improvSight readingObviously, these areas don’t apply to all levels of skill, but the point is to break practice down into granular areas.

When it comes to how to memorize a song, for instance, you might dig even deeper into the theory component and study the modes.

You just have to self-identify where you need improvement the most and then make a plan to fill in the gaps. If you’re not able to spot these areas on your own, this is where a coach can be very impactful.

Deliberate Practice ExamplesWe’ve just discussed how a musician might break their practice down into several key areas.

This principle applies across multiple disciplines, so let’s have a look at a few.

Deliberate Practice in Language LearningOne of my favorite ways to apply this form of practice is learning new words and phrases in a foreign language. It works well at any stage, beginner, intermediate or advanced.

There are a few ways to apply deliberate practice theory to language learning.

First, you can make sure you hit the Big 5 skills in meticulously scheduled doses:

Committing new words and phrases to memoryReadingWritingSpeakingListeningBut another way you can apply this form of practice to language learning is in how you approach memorizing phrases and vocabulary.

For example, let’s say that you’re learning a sentence in German like “Das Blaue vom Himmel versprechen.” It literally means the blue promise from the sky to indicate a promise that cannot be fulfilled.

If you find you get stuck on such phrases, a simple way to practice it more efficiently and ease it into long term memory, involves breaking it into 2-3 parts.

Das blaue vomVom HimmelHimmel versprechenI tend to prefer starting in the middle and working on just two or three words in a loop. Then I add the end to create a longer loop before going back to include the beginning.

Incidentally, I adopted this approach from music, where it is very common for students to make the mistake of going back to the beginning of a song when they make a mistake. Instead, if you take a single bar and loop it in this exact same manner, you’ll help erase the mistake without having to replay the whole song.

This kind of laser-focused, purposeful practice helps make sure that you’re weeding out problem areas while allowing your brain time to process the whole.

Deliberate Practice in Painting And ArtWhen I taught film studies, we talked a lot about the “deep narrative” of a story, which is why my ears picked up when I read the artist Tanya J. Behrisch on the principle of “deep time” in art.

In brief, time spent in nature or plein aire vastly improves your technique. This is quite different than deep narrative techniques where filmmakers use an economy of means to create sometimes vast universes in your mind in just 2-3 hours.

The theory makes a lot of sense. For example, the more time you spend studying exactly how the light of the sun illuminates a particular shade of green on a specific kind of tree, the more likely you’ll be able to express it in ways that create both recognition and unexpected emotional impact.

How exactly do you practice deep time as an artist?

By actually using your exposure to nature to mix your paints and get them on the canvas. The artist’s sketchbook and consistent studies over time help create an observation loop as they track their progress over time. Artists can also detail the exact nature of their experiments and innovations for future reference.

As the artist Behrisch puts it, deep time is needed to learn what the environment being painted has to say. There is a physical dimension, according to Behrisch, that amounts to allowing the senses to take on the life of the environment in a way that directs the artistic choices of color, stroke, shade, perspective and other aspects of image creation.

SFU Morning by Tanya Behrisch, 2008.

Deliberate Practice in WritingI’ll never forget when Professor Leps remarked about Roland Barthes that he was a remarkable writer precisely because he wrote masterfully in so many different genres. He wrote theory, philosophy, criticism and addressed multiple disciplines.

Leps said this to a class I took at York University back in 1998 and her observation influenced me to write in as many genres as possible myself. Doing so has helped me improve as a writer for reasons we’ll discuss in a moment.

But in order to gain any level of skill in writing, one needs to develop several levels of understanding. Each needs intentional practice in order to grow one’s skills as a writer. Here are four that have been particularly important to me:

DictionGenreTheoryStructurePracticing diction comes down to style, the specific words you choose to use. This requires the practice of writing itself, but also observation of how you naturally write in comparison with your observation of others.

Genre, on the other hand, requires a study of situations and various kinds of plots. For example, there are at least two kinds of tragedy.

In one, the protagonist fails to recognize his or her errors. In another, the protagonist does have a moment of recognition, but only after it is too late for correction. It takes dedicated study and actual time spent writing within a genre to begin to spot these types. Otherwise, it’s all too easy to take a genre like tragedy for granted.

Theory will help you spot these structures with greater ease. But even understanding theory can take practice. But the more that you combine study with implementation, the deeper your understanding becomes and the better you’re able to practice the craft.

Writing is also a physical art. It requires consistency over long periods of time. The first draft of my latest book project took 44 days with a minimum or 2000 words per day. I did that while continuing to write for this blog, where each article averages out to between 1700 and 2000 words. Given that I’ve written over two dozen books and hundreds of articles, I can tell you that stamina is something you build through consistent practice. No one is gifted with it from on high.

As an example of how I trained my stamina, here’s a practice I still use to this day:

I have trained myself to write for as long as one of my favorite albums takes to play from beginning to end.

For years, most of the posts on this blog were written while listening to just one album. Because I find editing extraordinarily tedious, I typically will use a separate album. A book written while listening to Nevermore may be edited while listening to Lou Reed, for example.

“Entraining” your brain to write by listening to the same music during each session could be a powerful deliberate practice technique for you.

You don’t have to take my word for that training using intentional practice matters. Stephen King says as much in his own words in On Writing and also talks about writing to music. Likewise, I learned about the importance of writing consistently from Susan Swan, under whom I studied writing at York University.

But to be as clear as possible:

I treat writing an entire book very differently than I do writing for my blog. Whereas a blog post can be drafted in an afternoon, a book may take weeks, months or even years.

Furthermore, successful blogging has certain rules and principles in order to reach audiences who typically use search engines to find answers to questions.

Books, on the other hand, go much deeper and can use a variety of structures. For example, most of my books are like manuals. But when I wrote The Victorious Mind, I practiced combining the delivery of raw instruction with scientific journalism and autobiography. I took inspiration from books like Moonwalking with Einstein by Joshua Foer and Suzanne Segal’s Collision with the Infinite.

The point is that you need to practice the principles that are related to the genre and the structure you’re creating in while allowing theory to guide your diction.

Critical Thinking and Deliberate PracticeAs a final, briefer example, let’s look at critical thinking. This is an important skill that cannot develop without consistent practice.

As Becki Saltzman puts in in her LinkedIn Learning course, Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset, you need to create a practice routine that integrates this form of thinking into your daily life.

She shares that she poses one question to herself each day of the week. The question may cover:

Issues at workMedical decisionsSocietal debatesTrending ideasShe goes even deeper by dividing the kinds of questions she practices by day of the week:

Monday = a purpose question (is my purpose properly aligned?)Tuesday = an information question (what are the best resources I need to look at?)Wednesday = a question question (what am I failing to ask?)Thursday = a perspective question (what perspectives am I leaving out?)Friday = Assumption question (what assumptions have I left out?)Saturday = Concept question (how can I better clarify one of my ideas?)Sunday = Conclusion question (how can I find better evidence to support my ideas?)

But practicing critical thinking using this structure, Salztman promises outcomes that I believe are very true:

We will make fewer mistakes and achieve intellectual humility. In other words, this form of practice keeps us open to learning more because we acknowledge that we do not know what we do not know.

For more ways to practice in this area, check out these 9 critical thinking strategies.

Deliberate Practice in MeditationOne of my favorite ways to apply deliberate practice is in mindfulness and a style of concentration meditation that is a bit more robust than other traditions.

In addition to daily sitting, this approach involves memorizing and reciting Sanskrit from a particular philosophical tradition.

Then, throughout the day, when unwanted thoughts arrive, specific statements “neutralize” them.

When pleasant mental experiences arise, deliberate practice is used to strengthen the positivity. The specific statement I make is “deepen, deepen” while focusing on the pleasant aspect.

According to renowned meditation expert Shinzen Young, this process creates a positive feedback loop. In other words, the more you label the pleasant experiences, the more pleasant experiences you have to label.

In this same discussion with Young, Leigh Brasington called the outcome of this process “Ecstatic Meditation.” He gives instructions on how to practice in his book, Right Concentration.

For more exercises that help you practice meditation intentionally, please also consider reading The Victorious Mind.

According to Campitelli and Gobet in Deliberate Practice: Necessary But Not Sufficient, the success of deliberate practice may not come down to the amount of hours you spend on a skill. At least not entirely.

Looking at chess, they found that other factors were involved, such as:

General cognitive abilityThe age a person begins to practiceHandednessThe exact season of birth (due to exposure to viruses more or less prevalent during particular parts of the year)Don’t let these findings discourage you. The researchers focused strictly on chess, after all.

But I mention the research because knowledge can give you mental strength that leads to identifying issues and helping you find solutions.

Ultimately, the real reason deliberate learning works comes down to the neurochemistry of habit formation.

Some of the best and most accessible resources on the science behind how the brain helps you form positive habits are found in books like:

Atomic Habits by James Clear59 Seconds by Richard WisemanThe Talent Code by Daniel CoyleI’ve already given an example of how I’ve put this science to work in my own life. Whereas I never used to believe that I could write for a living, by simply committing to write 2000 words a day each and everyday, I completely rewired my brain. It’s now very difficult for me not to write at least that much in the same way some people crave exercise… or junk food.

I think you get the picture:

Repetition is what forms habit, good or bad. The trick is to focus on repeating the good things enough times that your brain chemistry takes over and you crave the repetition of the steps that lead to positive outcomes. Even if effort is involved, you will ultimately not have a hard time showing up to do what works.

And on those days when you still struggle, you’ll have metacognitive tools provided by intentional practice itself that will help you “troubleshoot” the issues and neutralize them.

How to Use Deliberate Practice to Master AnythingNow let’s get into the good stuff: Exactly how to apply deliberate learning to the skills you want to learn.

Although there’s no perfect way to order the exact steps involved, I’ve been practicing presenting information in logical order. But this is where learners sometimes get hung up:

You don’t necessarily have to execute anything in the exact order it’s presented. Once you have the bird’s eye overview, recreate the steps in the manner that makes the most sense for you. And if things don’t work out, come back to the training and start again. As you’re about to discover, reviewing your steps through critical observation is a huge component of your success.

Know the Key Components of the SkillAlthough a skill like archery might look like one swift moment when practiced by a pro, it’s actually the combination of multiple small moves.

In order to practice effectively, you need to identify those small moves and work out ways to practice them as independently as possible. In painting, it might be devising color mixing from outlining shapes. In music, it might be differentiating rhythm studies from learning the exact notes in a scale.

The more you can map the territory into its component parts, the easier it will be to navigate the whole.

To give you another example, in the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass, I help people focus on the Memory Palace technique first. Then we move into visualization skills related to association before linking them back to the initial technique. In this way, we establish one foundation at a time and then go back and strengthen that initial foundation through a process of review.

Plan Based On the ComponentsOnce you’ve identified all the different parts that are involved in a skill, create a plan of attack. As we saw with the critical thinking example, Saltzman spreads her practice across the entire week.

You can also refer back to the method of splitting things up that I shared in the music and language learning examples. Instead of tackling a whole piece, you can look at just parts of things on specific days.

For example, I often teach my serious memory students to prepare what they want to memorize early in the week, practice encoding it during the middle of the week, and then practice decoding the information during the end of the week.

Obviously, this particular suggestion can be modified in different ways. If you don’t want to split the sessions across an entire week, you can split them into morning, afternoon and evening. Experimenting to see what works best for you is the fastest way to settle on a strategy that provides consistent and substantial results.

Embrace DiscomfortThere’s a reason many experts say that you have to get outside your comfort zone. Taking action not only requires energy and focus, but you also can never be sure that the expenditure will pay off.

That’s why it’s important to let go of the outcome. Perfectionists have an especially difficult time doing this, and they often benefit the most when they’re finally able to let go of control. The reality is that no one can actually control anything that’s going to happen in the future, so the sooner you accept this unsettling fact, the sooner you’ll benefit from practicing without concern for how the session will go.

That said, you still need to monitor your practice. As you do, simply observe any discomfort. Label it, but do not judge it.

If you need help with this step, here are two questions you can ask if and when negative thoughts about your practice results arise.

Capture and AnalyzeWhen I taught at Rutgers, my boss Dr. Spellmeyer gave me one of the most useful tips I’ve ever encountered. He said to never make more than three corrections on an essay I was marking.

The reason why is that too much feedback overwhelms students and prevents them from perceiving the value of what you’re offering.

Since that time, I myself have asked my own teachers to limit their feedback to just three corrections, especially in language learning. This area in particular requires a lot of courage, especially when it comes to speaking practice. If you’re interrupted constantly while trying to speak, it can shatter your confidence.

For this reason, I suggest you apply the three-corrections rule to yourself as well. The catch is that in order to find areas for correction, you need to actually capture your practice.

Fortunately, that’s easy these days. Back when I started magic, I used to record myself with a camcorder, which meant having to hook it up to a TV in order to watch the footage. But these days, it’s easy to use my desktop, laptop or phone to get instant feedback.

Likewise, anytime you meet a tutor on Zoom, there’s a one-click process to get the session recorded. It’s easy to review the material multiple times so you can analyze your own errors.

Just don’t overdo it. Try to focus on only three things at a time and you’ll give yourself space to work on the big issues. You’ll have great mental clarity for the granular details on your second pass.

Work in 90-day BlocksAlthough I’m sure it’s influenced by all the years I spent attending semester courses at university, I think there’s a lot to be gained by practicing in 90-day blocks on particular skills.

For one thing, a lot of the neuroscience resources I shared above show that 90-days is a kind of sweet-spot for habit formation.

To help portion out these blocks of time, I have found The Freedom Journal useful. The best part about a tool like this is that after using it once or twice, your brain is well-trained to repeat the process without relying on an external device.

Rest Like A ProAs the cliche goes, all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.

This phrase is instructive because not all of us feel rested by sitting around doing nothing. Some of us get our rest by engaging in alternative activities that help us express our skills in different ways.

Alex Soojung-Kim Pang brings this point out in his book Rest. I took two of his suggestions to heart and combined them:

Take a sabbaticalApply your skills to something else entirelyI mentioned earlier that my latest book project took 44 days. But I didn’t mention that it was not about memory – at least not directly. I wrote a novel instead.

Although it still took energy and focus, I felt remarkably refreshed at the end of each writing period for the reasons Pang uncovered in his research. The skill of writing is being exercised, but in a completely novel way. This makes the activity as restful, if not moreso, than if I’d done nothing at all.

But whatever you do, it’s important to know what counts as restful for you. And it would be remiss if I didn’t point out that rest itself must be studied and practiced with intention and structure.

Miss Out on Intentional Practice At Your Own RiskAs I hope you can tell by now, you have every reason to practice with focused intention. There’s literally nothing to lose.

True, practicing in the ways we’ve discussed today requires setup and review. This process must also be repeated as you make your way on the path of mastery.

But isn’t this precisely what mastery is?

When I use the term “memory master” on this blog, what I mean is precisely that: the person who consistently practices their memory with no concern for the outcome.

Yes, there’s the paradox that we need to observe the outcome in order to improve over time. But life is full of contradictions, and learning to accept them is part of how we make progress. You can learn to let go of the outcome and analyze it all the same.

And if you’d like help with this process when it comes to memory improvement, give this FREE Memory Improvement Kit a try:

It will reveal the secrets of how everyone from ancient learners to contemporary memory athletes learn faster and remember more.

You’ll learn exactly what needs to be practiced and how to document your journey so you can improve your results over time.

And let me know in the comments:

What outcomes do you want and how willing are you to put the key characteristics of deliberate practice to work in your learning life on a scale of 1-10?

November 17, 2021

David Perell On Writing, Learning In Public And Why Spaced Repetition Sucks

David Perell is an author who helps people excel in what you might call the business of creativity.

David Perell is an author who helps people excel in what you might call the business of creativity.

And frankly, I think he’s a memory artist too.

For example, everything that has to do with writing winds up involving the most positive form of spaced repetition. It’s like the ultimate mnemonic device.

But it’s not traditional spaced repetition or rote learning.

It’s creative repetition.

But these matters aren’t the only reason I wanted to interview David.

I’m also interested in how he’s using technologies of today to educate people.

As the founder of Write of Passage, David helps people generate ideas systematically and transform them into living, breathing and published pieces.

He is doing this though cohort-based training programs online and has been generating incredible results for people who tired of ineffective writing methods.

If you’re interested in expressing yourself through writing and developing career-level chops, definitely check his program out.

As I often like to say, writing is the source of all wealth. I believe it is also a key source of memory too.

Enjoy this conversation and I hope to hear from you in writing soon!

November 11, 2021

How to Read a Book and Remember Everything

If you’re wondering how to read a book and remember everything like a professional scholar, this is one of the most helpful tips I can give:

If you’re wondering how to read a book and remember everything like a professional scholar, this is one of the most helpful tips I can give:

Sit down, open a book and read.

Of course, I have more secrets to share than just that.

But isn’t common sense powerful?

It is.

And it’s getting even more powerful as modern life creates more and more distractions and demands on our attention.

Of course, we can (and will) talk about different types of reading, like elementary, inspectional, analytical, and syntopical reading.

These are terms introduced by Mortimer J. Adler in his famous guide, How to Read a Book.

But these terms are useless if you don’t:

Schedule time to readRead according to demands of the genreRead based on clearly established goalsBe prepared with the appropriate tools for interpretation and analysisSo if you want to know the best way to read, I encourage you to explore ways to read.

That’s because there are multiple kinds of books.

And when you have a toolbox of strategies at your fingertips, you’ll be able to read faster, remember more and even better:

You’ll understand what you’re reading and become a person of knowledge and wisdom.

You’ll make connections on the fly and experience multiple a-ha moments of revelation.

Sound good?

Let’s get started!

The 4 Main Types of Reading (And Which Is the Best Way to Read a Book)What’s the point of reading?

There are several, including:

For school assignments and examsFilling in gaps left by traditional educationDeveloping personal wisdomSolving problemsExpanding mental awarenessSubstantial reflectionIdentifying or creating opportunities for yourselfResearch as a professionSpiritual goalsLeisureEach of these categories can involve multiple reading types.

Let’s start with the oft-cited types identified by Adler in How to Read a Book.

I’ll cover Adler’s main points, and after that, we’ll talk about how to read a book like a scholar so you can remember as much as you want.

Why should you care what I have to say about reading?

Well, I have a PhD, two MAs and am an author of many books. Most of those books involve tons of research.

I’ve also taught reading and writing at three universities around the world, including for Rutgers where the legendary Kurt Spellmeyer was my boss.

Oh, and I read every single day, completing 2-5 books a week on average. All kinds of books from fiction to philosophy, science and Zen.

You name the category, and I’ll probably have read something that belongs to it.

And if I haven’t, even if the category is crushingly complex, I’ll figure out a way to increase my IQ in that field to the best of my ability.

All right, enough about my street cred. Let’s get started with Adler’s four main types of reading.

One: Elementary ReadingAdler says that this reading type hardly goes past basic understanding.

You know what the words on a page say, and you can follow a basic plot.

However, I think we need to add a very important point.

Elementary reading is often directed reading.

You’re told to do it by a parent or teacher.

It’s the opposite of self-directed reading.

And that’s a big problem. As the authors of Balancing Principles for Teaching Elementary Reading argue, one core value matters above all.

Teachers and parents should strive to help kids want reading as part of their lives.

Why is this so important?

Because literacy demands are only going up as technology and automation increase.

Not only that, but critical thinking is so important to the success of all people.

In fact, there are 9 critical thinking strategies all people need, but if you only have elementary reading skills, you cannot develop them.

And no, you can’t expect so-called microlearning to help fill in the gaps if you’re an elementary reader.

Will inspectional reading get you there?

Let’s see.

Two: Inspectional ReadingFor Adler, inspectional reading is what most people now call skim reading.

Adler seems to confuse it with scanning, which is substantially different.

Don’t get me wrong.

There’s nothing wrong with inspectional reading. As the authors of Reading as a Perceptual Process have shown, words can be skipped while scanning a book without the reader necessarily losing comprehension.

However, the most interesting finding in the book is that how much you can still understand while inspecting a book may be linked to handwriting.

For example, they analyse “target scanning,” which is stronger in those with decent handwriting skills.

This means that if you never write by hand and are finding it difficult to grasp the meaning of books you’re skimming through using “speed reading” techniques, you might improve by practicing your longhand writing instead of typing.

Whether or not doing a lot of typing helps your “target scanning” for any kind of reading on screens is yet unknown.

But there are also aren’t a lot of people who have talked about inspectional reading from devices because digital books aren’t quite so easy to scan.

Either way you look at it, I’ve chosen to read from print instead of digital. The benefits are too profound, especially when you’re using memory techniques.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=er-k8...

Three: Analytical ReadingA lot of people worry that reading without understanding wastes time.

I disagree.

Rather, I read so that I might understand.

After all, if I already know what a book is going to cover… why bother reading it?

Well, Adler had an answer for that. He called it “superficial reading.” It’s technically part of inspectional reading, and not exactly the opposite of analytical reading.

For example, you might be perfectly justified to read superficially if you’re just looking a book over to see if it covers anything new or surprising.

But if you really want to dig deep into a book, you need tools of analytical thinking. Even if you’re familiar with the topic and the book is repetitive, you still need to perform what can also be called a “close reading.”

What’s involved?

A lot, frankly.

Genre

First of all, you want to understand the book’s genre or category.

Why is this important?

Because it will help you connect the book to other texts that directly relate to it or hold an important connection. Knowing the various fields of knowledge speeds up your pattern recognition.

Classifying texts by their type is so important, I created an entire course about it called Genre Frameworks.

Composition

You also need to understand how the book is put together.

This is called the form/content paradigm.

In other words, how a book is written forms part of its ultimate meaning.

For example, Plato’s Republic is a dialog. This formal aspect influences the meaning of the philosophical ideas in the text. They are discursive and combine objective and subjective reasoning in ways that only the dialog form can.

Aristotle’s philosophy, on the other hand, is presented in direct prose. It is argumentative and designed to convince you that his points are valid.

Paraphrase and Summary

Analytical reading isn’t just about reading.

Adler wants you to be able to restate the points in a book in your own words.

Developing generally involves writing about what you’ve read.

This is critical because A+ students get those grades by producing variations of assigned readings.

Think of it like music. If you know a scale, you can play it forwards and backwards. But you can also perform the scale in your own style.

I use the music metaphor because writing about what you’ve read should be combined with talking about it too.