Anthony Metivier's Blog, page 12

March 22, 2022

How to Overcome a Memory Block (Guide From a Memory Expert)

My worst mental block happened back in 2008 while giving a lecture.

My worst mental block happened back in 2008 while giving a lecture.

I was standing behind the podium when a huge panic attack burst inside my chest.

Although I’m usually very good at remembering what I want to say, when I want to say it… during that moment, I found myself speechless.

I had no idea what I had just been talking about and couldn’t find the thread needed to get myself back on track.

Embarrassed beyond belief, I dismissed the class and retreated home. I decided I would never be caught cold like that again.

Fast-forward to February 2020. I made a small error while delivering a TEDx speech.

Using the techniques you’re about to discover, I rapidly recovered because I not only had the thread firmly in my hands. But overcoming mental blocks under pressure has become my speciality.

Are you ready for all my best tips?

Great! Let’s get started!

What is a Mental Block?Mental blocks can be defined in a few different ways. I think Tobore Onojighofia Tobore gets the definition best when he relates the sudden inability to focus and remember to a failure of learning and mental representation.

Tobore gives us an important way to think about it because mental blocks can happen to anyone, no matter how skilled or experienced they might be.

There are also levels of mental blocks a person can experience.

For example, think of the difference between writer’s block, when the person can’t write at all, and writing a bad book.

An experienced author should know better than to produce second-rate work, yet even Stephen King has admitted in On Writing that he’s capable of producing a dud. He may not have been blocked from writing altogether, but something in his brain failed to remember what makes a story great.

Likewise, a student can show up to an exam and often remember enough to answer the questions. But they might struggle to recall the nuances that make the difference between a C+ and an A.

Tobore thinks that it boils down to the strength of your neuronal connections and their resistance to disruption.

If Tobore is correct (and I think he is), this means that the typical explanations for why we experience mental blocks are incorrect.

Typically, we’re told that we experience them when we’re:

OverwhelmedTiredStressedUnrestedAlthough these states certainly can contribute to poor focus and an inability to access memory (stress in particular), they are not strong explanations.

We know this because many people who play Jeopardy, act on stage or give speeches face all of these factors and yet still perform well. Athletes also have to access procedural memory under grueling conditions, so it just doesn’t make sense that these oft-cited factors are to blame.

I know from personal experience that they aren’t to blame because I often perform perfectly well despite suffering all of the above issues, including chronic pain.

So if we can’t point the finger at those issues, what factors do reliably explain our mental blocks when we have them?

One: Lack of PreparationMost people experience blocks because they simply haven’t prepared themselves thoroughly enough.

They may have skimmed or scanned books instead of reading them thoroughly. This prevents the brain from forming enough connections to frame a complete enough picture. Instead of a study foundation, you wind up with sand that easily blows away in the wind.

When I had my panic attack in front of the lecture hall, I was still a rookie. A huge part of my problem was that I hadn’t put a lot of thought into how I was going to end the lecture. I was okay up until the close and thought I could wing it. But I was wrong and that led to me experiencing a massive mental block.

Two: Lack of PracticeAs a professor, I’ve marked hundreds of exams and essays.

It’s easy to spot the work of students who have put in the practice and those who have not.

When I myself had field exams and a dissertation defense to pass before getting my Phd, I practiced each and every one. It was as simple as getting friends to test me and following the rules around what is called dedicated pactice.

Performance-wise, when I gave my TEDx Talk, I wasn’t feeling all that well. But it didn’t matter because I’d practiced reciting the talk multiple times. I’d even memorized it and written it out by hand three times to make sure I knew it inside and out.

That way, no matter how tired, overwhelmed or stressed I felt, I knew I could rely on memory consolidation alone both in terms of the procedural memory of delivering the talk and semantic memory of the words and phrases.

Three: Communication ChallengesSome people have congenital issues or brain disease. For example, some people might suffer from aphasia and need to be trained to rely on formulaic speech patterns. But because the flows of normal speech are not necessarily tidy, people with these issues can quickly find themselves blocked.

Although you could interpret such situations as “overwhelm,” it is a very specific kind of overwhelm based on the fact that parts of the brain have been impaired.

Looking back at the panic attack I had in the lecture hall, it happened during a time when I did a lot of drinking. This left my brain dehydrated and because I privileged alcohol over nutritious food, it’s little wonder I couldn’t even innovate a conclusion to my talk that day.

It’s easy to get caught like a deer in headlights when a mental block arises. Instead of easing your way out of it, you wind up doubling down on the symptoms. This happens because your brain focuses on the problem instead of possible solutions.

Options include:

Taking a few deep breathsGetting a drink of water and/or a snackTaking a walk or stretchingIf you’re in an exam, you might be pleasantly surprised by how generous your examiner might be if you need to take a break. But if you hyper-focus on the problem, you might not even think about asking.

In the case of my lecture, I could have easily excused myself for a moment and used a few breathing routines I knew to bring myself back to center. I was too involved in the panic attack itself to even think about pursuing this possible solution.

You might doubt that taking a few deep breaths will help. However, studies have shown that there’s a relationship between breathing and memory formation.

Five: Negative PatternsRelated to focusing on the mental block itself, it’s easy to repeat negative thoughts that make the problem worse.

For example, students often tell themselves during exams, “I don’t know this!” They repeat the statement like a mantra instead of moving on to the next question and coming back to where they’re blocked.

Even as a person experienced at speaking and taking multiple exams, that day in the lecture hall, I found myself repeating, “I’m freaking out!”

Although it can be good to acknowledge whatever state you’re in, you need to label it as fear, not participate in the fear. This is an important finding of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), which reveals that people are often more afraid of the fear itself than they are of the consequence of failing or looking silly because they forget what they were going to say.

Research in this area is relatively new, but some researchers have found that practicing giving public talks in a virtual reality environment can help people with public speaking anxiety learn not to get into such mental downward spirals just as well as CBT. Such findings substantiate Tobere’s argument that mental blocks ultimately come down to the strength of memory consolidation at the cellular level because strong neural connections help prevent falling into the spiral in the first place.

How to Overcome Any Memory Block in 9 StepsNow that you know what really causes mental blocks, let’s look at removing them on demand. These suggestions will work no matter how overwhelmed or stressed you might find yourself.

Do they require extra effort?

Sure.

But at the end of the day, it’s usually the absence of effort that leads to the problem in the first palace.

And since you’re here, you obviously want to be a top performer. Let me share my best solutions, earned from the trenches of having suffered myself from mental blocks.

If some of my solutions seem quirky, it’s because things like getting enough sleep or chatting with friends just weren’t options for me.

Plan Ahead and Finish EarlyI suffered anxiety for many decades, not just during my first years as a university professor.

As an undergrad, one of my go-to strategies for making sure I got top grades involved discovering what would be required of me as far ahead as possible.

To do this, the moment I knew what courses I would be taking, I would email my professor and ask for the course syllabi. They weren’t always willing to give them ahead of the class start day, but often enough they would.

Then, I would get the exam and assignment dates on my calendar and start reading. In courses where I had to wait for the start to get this information, I would immediately add those dates.

Because I usually worked at least one, but sometimes two or more jobs while studying, I reduced my stress and overwhelm by starting the essay assignments early. When professors were receptive to it, I would hand them in early as well and try to get advance feedback. That way I could improve them before the due date and get even better grades.

This might seem over the top, but the top grades I earned helped in earning scholarships that kept my student debt as low as possible. As a result, I had much less stress.

Customize the QuestionsIn my last year as an undergrad, I was required to complete a fourth year level course in Romantic literature.

I loved the topic, but for some reason, the professor was hard on me. When I asked for an alternative assignment to giving an oral presentation because I was still getting used to shaking from lithium I had to take, he made me spend my precious study time getting a letter to prove that I had the issue. And he wouldn’t accept the letter from my doctor. He wanted it from a counselor at the university’s Behavioral Sciences department.

When I finally got the alternative assignment, he made me read Goethe novels that were 3x longer than the material I would have read for the oral assignment. This meant that I had less study time for the final exam in the course.

During the final exam, I was unprepared for an entire question on a play called Cain by Lord Byron. Rather than leave the question blank and accept a zero for such a huge portion of the exam, I scratched out the question. In its place, I wrote, “Explain the difference between Coleridge and Wordsworth’s approaches to Romanticism.”

I’d relied on this tactic a few times before and thought for sure that this particular professor would still give me a zero. But as things turned out, I passed the course with an A.

Learn and Practice Depth RelaxationI have been interested in meditation since high school. But it wasn’t until my PhD years that I really got into practicing it seriously. And as part of my research into friendship, I took a course to become a certified hypnotherapist, largely to explore the role of persuasion in friendship.

In the hypnotherapy program, I learned to relax myself deeply on demand. The guided visualizations I learned to create for myself were golden. I still struggled with panic attacks from time to time, largely because I still drank and would sometimes show up unprepared, but overall, I enjoyed a much more relaxed life.

One thing that I’ve found tremendously helpful is to relax while studying. Like Pavlovian conditioning, it seems to help bring the feeling of relaxation back when drawing upon the material. Although not entirely scientific, the advantage this brings possibly relates to what is called context dependent memory.

One reason we experience memory blocks that we can’t get out of is that we simply don’t have a wide enough frame of reference.

But by expanding what we know through effective reading strategies, we’re less likely to get blocked in the first place. Our minds will find related topics to discuss or near-substitutes.

All people get mentally blocked, but if you watch enough smart people give talks or interviews, you’ll notice that they are expert at finding detours when the perfect answer doesn’t immediately come to mind.

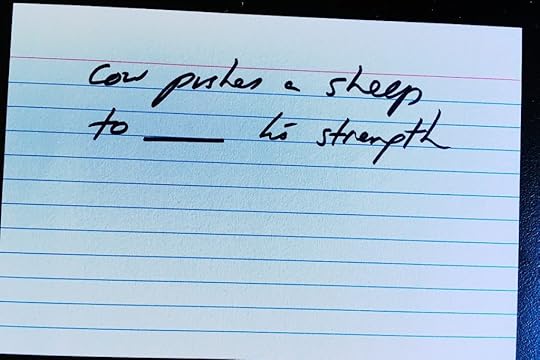

And the best speakers of all will use rhetorical devices. For example, they’ll say, “I’ll get back to this in a moment, but let me first talk about _____.” Often, when an expert uses a phrase like this, it’s because they’re buying time.

Place the Focus ElsewhereAlthough I’m a memory expert, I sometimes can’t find the word or reference I’m looking for. When this happens, I simply call a spade a spade and say, “It will come back to me.”

Usually, simply by being willing to admit what’s going on in my mind and focus for a moment on something else, the original thought I was looking for pops up on its own.

Consult the AlphabetSometimes when I can’t find the names of people I’m looking for, I choose a simple strategy instead of getting frustated.

It happened to me today, for example. I was thinking about Dan Harlan, and for some reason, his last name just wouldn’t come to me.

Why?

Well, I was tired. Hungry. And frankly, I had no particular big reason why I needed his name at that moment.

Nonetheless, I’m a person who works on my memory, so I wanted to remember it.

One of my favorite tactics to nudge such information out of memory is to simply run through the alphabet. Like this:

Dan A…?Dan B…?Dan C…?Etc.I actually went past H without getting it, but it wasn’t much further before his last name popped into my mind.

The next step is to use memory techniques, which we’ll discuss next.

Use Memory TechniquesThat said, if you use the Memory Palace technique effectively, such mental blocks will happen to you much less frequently.

The trick is to use the technique properly. It’s a real skill and like other skills, can only serve you to the extent that you master it. If you need help learning to use it, register for this FREE COURSE:

In it, I’ll guide you through a number of simple exercises and steps to follow so that you have multiple Memory Palaces.

Here’s a simple use case:

To make the name Dan Harlan stronger so I get it more immediately the next time, he is placed in a Memory Palace. In this case, it’s a building I’m aware of in Harlem, New York.

I imagine him standing out side of this location with a giant harpoon. I choose this image because harpoon has the Harlan sound in it.

Then I have him harpooning a LAN Internet device with a Lando sticker on it (the character from Star Wars) in that location. After visiting this association a few times, Dan Harlan’s name should come back with much greater ease in the future.

Use Other Accelerated Learning TechniquesThere’s a vast world of tactics you can use in addition to memory techniques. You can learn to read faster and mind map, to take just a few examples.

However, don’t be a dabbler. None of these techniques will help much if you don’t pay them their due. And that’s why the next point is so important.

Practice ThoroughlyAs I mentioned above, I’ve spent a lot of time practicing for exams and presentations.

When it comes to practice, the amount of time you practice usually isn’t as important as what you practice during the time you have.

Plus, you have to think deeply about the exact area you need practice in. How you practice for taking tests will be different from practicing to give a speech or to perform a magic trick.

Know what the masters in your field practice and model them so that you know you’re maximizing the time you have at your disposal.

By getting out there and taking the exams or giving speeches from memory, you’ll give yourself important frames of reference. If you don’t make mistakes, it’s hard to see what to improve.

Develop the Right AttitudeIn The Positive Mental Attitude Pocketbook, Douglas Miller talks about having “firelighters.”

These help you stop mental blocks and get back on track. They include:

Avoiding limiting descriptions of yourself, (i.e. I’m a failure)Find the source of the problemEvaluate the situation from a broad perspectiveDon’t let one failure derail you completelyExpect future successEach of these points have helped me tremendously. Whereas I used to repeat negative phrases about myself compulsively, now I recite Sanskrit phrases I’ve memorized instead. Instead of thinking the smallest failure is the end of the world, I zoom out and think of all human and cosmological history and how my life is merely a speck in the grand scheme of things.

And regular readers of this blog might find this surprising, but I not only expect future success. I expect and embrace future failure too.

I know that mental blocks are coming, but I keep moving forward anyway. Case in point:

At the very end of my Read with Momentum program, I was tired after seven hours of live streaming. I probably shouldn’t have tried a memory demonstration, but I believe in taking my best shot anyway.

Names had come up, and to help answer some questions for Robert, I pulled up a software used by some memory competitors.

Now, I actually didn’t do that bad when I typed out the names, but I made a critical error. I was so hyper-focused on encoding the names that I didn’t pay attention to the faces on the screen. But instead of getting blocked by this obvious failure, I opened a new tab and typed out what I remembered anyway.

I fully expect that if I’m going to continue this work, I’ll wind up making “errors” like this in the future. It’s just part of what’s involved in memory as an art, craft and science.

But if you have the right attitude and expectations, you’ll always learn from whatever happens. And in the future, you can use those past experiences as “firelighters,” as Miller calls them.

Say GoodBye To Memory BlocksWe’ve talked about a lot of circumstances in which you can experience a mental block or temporary memory loss.

A subtheme throughout today’s tutorial is that life itself is a kind of exam.

When you treat it that way, and always show up prepared to do your best, you’ll do so much better.

As a final thought, I would suggest that you be willing to let go of the outcome. As I often tell my memory students in the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass, you have to be like a samurai. You have to be prepared to execute one final perfect move, even with your head cut off.

In the memory demonstration that failed, I did my best to squeeze in one more name than I thought I could.

Although I wasn’t able to place the names next to the faces, the names I did recall were mostly correct. And I had one syllable for one last name that I hadn’t even mentioned during the demonstration.

True, the demonstration was far from perfect. But the one last move, the one I made while admitting my head had been cut off, produced an audible gasp.

But it was only possible for me to have the guts to make such a mistake in front of so many people because I am willing to let go of the outcome.

And if you want to stop mental blocks from holding you back, I suggest you cultivate this skill too. When you do, you’ll develop the reinforced mental representations Tobore’s research has discovered. In other words, the more you practice being your best possible self, the easier it will be for that person to emerge, fully knowledgeable and perfectly capable, even when the chips are down.

So what do you say? Are you ready to treat life itself like an exam and show up with your best possible attitude?

March 17, 2022

Mental Stimulation: Everything You Need to Know About Brain Health

Did you know that you can use mental stimulation to cause new brain cells to grow and connect?

Did you know that you can use mental stimulation to cause new brain cells to grow and connect?

It’s true. The process is called neurogenesis and anyone can do it.

But you might lack confidence when it comes to understanding and using the techniques.

And I can’t blame you. Tinkering with your brain can feel scary.

But rest assured. I do it all the time, as do millions of others around the planet.

It’s safe, healthy and really does boost your brain.

So if you’re ready for a simple explanation of the science and a list of fun steps to follow, let’s get started.

What is Mental Stimulation?Think about the difference between your brain and your mind.

You’ve probably seen documentaries where surgeons use electrodes to stimulate parts of the brain. Sometimes touching a part of the brain causes the patient’s limbs to move. Other times, they might think they are smelling toast.

This is the difference between stimulating the brain’s connection to the body and its connection to mental imagery. Whereas brain stimulation that causes muscle movement is physical, stimulation that triggers a mental experience is mental stimulation.

Do the two types of stimulation ever combine?

In a word, yes.

One of the scientific terms for the physical aspect of brain stimulation is called “neuromodulation.” As Clement Hamani and his co-authors show in Neuromodulation in Psychiatry, manipulating physical brain structures has a long, and sometimes troubling history.

For example, gamma knife radiation, normally used to treat lesions and tumors, has been used experimentally to treat obsessive compulsive disorder. Some positive results have been seen in how such patients think and behave. But there have also been some not so positive outcomes as well.

However, this is not what we usually mean by mental stimulation. Usually what we mean are topics like the ones categorized by John Clement in Creative Model Construction in Scientists and Students: The Role of Imagery, Analogy, and Mental Simulation:

Using your imagination to mentally simulate experiences like using image streamingConducting thought experimentsUsing analogiesThinking philosophicallyReasoning through problems objectively and subjectivelySpatial reasoningPlaying a musical instrumentThe Impact of Mental StimulationThe benefits of such activities can increase creativity, memory, productivity, consistency, decision-making and goal completion.

Mental activity is key in each of these areas. As the co-authors of The Wise Advocate show, thinking in particular ways helps improve brain structures. It also helps new neural pathways form, helping people lead themselves and others much better.

Plus, you’ll also feel sharper when you stimulate the brain. The question is, what kinds of activities do this effectively and efficiently?

Let’s have a look at some of the best.

As we dive into this list, please beware of other lists that talk about improving your blood sugar, cholesterol or other aspects of physical health. While all of those things are good in themselves, to get the benefits of brain stimulation, we need to engage in mental exercises.

Authentic mental activities will stretch you. If they don’t, they’re probably not stimulating enough.

To make sure you’re getting proper levels of challenge, make sure that the activities you choose to get mentally stimulated involve:

Learning or relearningReasonable complexityVariationFrequent engagementIf you’re missing any of these criteria, make sure to include them in for a good brain workout.

One: Learn a LanguageOne of the most proven ways to increase what is called “cognitive reserve” is to study a foreign language.

What is cognitive reserve?

It is robust brain health that people free from Alzheimer’s and Dementia show in old age. It’s well-known that keeping your brain active throughout life, but especially in old age helps increase this aspect of mental fitness.

Some studies I’ve discussed in my post on bilingualism show that learning just one language can provide up to 32 years of cognitive reserve.

Luckily, learning a new language provides a range of challenges, and is also really fun.

Two: Study MusicMusic provides a similar level of challenge as language learning. There are at least as many ins-and-ands you’ll stretch your brain to accommodate.

Whether it’s learning the key signatures or the names of the notes for each string on a guitar, your brain will benefit.

Keep in mind that you don’t have to learn an instrument. Studies have shown that even just regular singing stimulates the brain so much, people who do it recover better from surgeries than those who don’t.

Plus, you can also stimulate your brain by learning about the history of different musical styles, along with the biographies of great composers and musicians.

Three: Long Form ReadingMany people graze in their reading. They dip in and out of things.

But long form reading stimulates your brain much more profoundly when you read:

Multiple books on the same topicA variety of books by the same author so your mind can build a paracosmSeveral books that compare and contrast topics to expand your perspectiveThere are many other reading strategies, but the three listed above are some of my favorites.

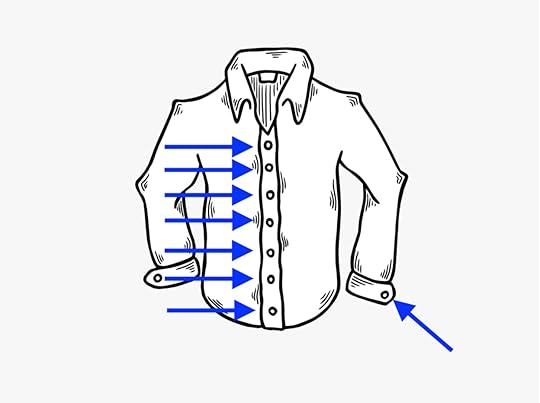

Four: NeurobicsIf aerobic exercise gets your lungs and heart to change their normal resting pattern, neurobics changes the normal patterns of your brain.

A simple example is changing your route to and from work. It can even be just a simple detour down a street you’ve never explored that awakens your brain.

Or, you can:

Brush your teeth using your non-dominant handUnlock your door with your eyes closedLearn to recite the alphabet backwardsFive: Brain ExerciseBrain exercise is controversial. Tons of companies have created apps that claim they will help keep your brain sharp.

However, as I discussed with Dr. Christine Till, there’s little to no evidence that they have any effect.

That said, there are a number of mentally stimulating brain exercises you can engage in that will stretch your figural memory. For example, you can imagine taking different letters of the alphabet apart and reorganizing them in unique ways.

Six: Puzzles and GamesSolving puzzles is very stimulating.

But I don’t mean crossword puzzles, where the temptation to cheat is strong.

I’m talking about physical puzzles that require you to complete a picture. For the strongest possible challenge, choose densely colored abstract images to work on.

When it comes to games, check out my list of the best adult brain games.

Many types of meditation are fantastic. But the most stimulating tend to involve chanting and mudras.

To get started, I suggest learning Kirtan Kriya. It’s good for reducing stress while improving concentration and memory.

For greater levels of challenge, memorize chants like the kind I discuss in my book, The Victorious Mind.

If you need help memorizing long chants, it’s also great mental stimulation to use a Memory Palace. You can ultimately tie this form of meditation back to language learning, such as by memorizing a book of chants in another language.

Eight: Develop Your Critical Thinking SkillsIn a world filled with so much gullibility and strife, it’s easy to stand out just by being a reasonable person.

But how do you get started if you’re currently struggling with falling for bad ideas and disinformation?

Here’s a simple exercise that Lisa Mendelman rightly argues sounds simplistic, but is incredibly effective.

As you read, circle the concepts and the images authors use to try and persuade you. For example, in this section, you might circle the word “strife.”

This in itself will help you think more critically. But to take it to the next level, start questioning while reading. Ask questions like:

According to whom?What’s the evidence?Who benefits if this claim is true?This kind of real-time reflective thinking is incredibly stimulating – and beneficial.

Can You Really Boost Your Brain?As we’ve seen, this is not really the right question. What we need to do is stimulate our minds.

Or course, there’s a time and a place for stimulating the physical brain, ideally with physical exercise.

But when it comes to stimulating the mind so that it really does get a boost, we need to challenge it.

I’ve shared a bunch of powerful activities on this page, and you can rest assured that your intelligence is not fixed. You even stand to improve your IQ if you set goals around learning and complete them.

For some people, the real challenge is going to be taking on the challenge in the first place.

And no doubt. Modern life is hectic. Many of us are tired. Digital amnesia has frazzled our brain and Johan Hari has gone deep into how and why this has happened in his book Stolen Focus.

But if you’re stuck, there are always options.

One of those options is memory training. It is perhaps the most stimulating option of them all because it works out multiple levels of your memory.

Get my FREE MEMORY IMPROVEMENT KIT now if you’re interested:

The mental stimulation you’ll receive in this course includes stimulation of your:

Spatial memoryProcedural memoryAutobiographical memoryEpisodic memoryShort term or working memoryLong term memoryVisual memoryProspective memory… and much, much moreAll you have to do is dive in and get started.

It truly is up to you. All you have to do is take that first step.

So what do you say?

Are you ready for some authentic mental stimulation? Stimulate yourself now by saying yes and I can’t wait to read your progress reports.

In case it hasn’t already leapt to your mind, engaging in correspondence is yet another powerful way to invite more mental stimulation into your life. All the more so when you’re taking on the challenge of expressing your experiences of taking on more challenges.

March 9, 2022

How to Remember What You Study (Almost Without Trying!)

Want the best way to study and memorize?

Want the best way to study and memorize?

Without all the pain and hassle of boring scientific explanations that are themselves hard to understand?

You’re in luck.

I’ve sat for some of the most competitive exams that exist over eleven years of university.

Despite many personal challenges, I managed to get my Ph.d. and have picked up many other certifications along the way.

I’ve even used what you’re about to discover to help me learn languages and earn certifications for both German and Mandarin.

So whatever you’re studying, I’m qualified to help you get some quick wins.

Ready?

Let’s dive in!

How to Remember What You Study Fast: 10 Quick-Win StrategiesLater, I’m going to give you a more robust strategy that will take you approximately one weekend to learn.

But we’re going to start with some powerful strategies that you can start applying today.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-95LB...

One: Get Your Mindset SortedNegativity is a major reason that so many people fail.

They play a little story repetitively through their minds about how “hard” everything feels.

Instead of focusing on the task at hand, they visualize the stress of the exam and the consequences of failure.

This is not helpful.

The alternative?

Relaxation and deliberately letting go of the outcome.

Simply being willing to fail if that’s what was going to happen was the number one strategy that helped me most before and during the toughest exam of my life.

Sound hard?

It isn’t really when you have mental strength exercises to guide you.

Even if mindset isn’t a problem for you, it’s useful to focus on the positive.

Two: Take Intelligent BreaksMany people force themselves to study for hours at a time.

You cannot expect to succeed by doing this – at least not many of us can.

Personally, I love studying for long periods at a time, but I do take plenty of breaks.

I get up, walk around, drink plenty of water and practice the next tip. It’s one of the simplest ways to help you study and remember.

During your breaks, you can also spend time on relaxation, meditation and breathing exercises.

Three: Switch Things UpThe special technique I use as part of taking breaks is to read other kinds of books.

They can be either related or unrelated to the topic at hand.

The point is to switch things up so that your brain has time to percolate the ideas you’re learning and make unexpected connections.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3U34n...

You don’t have to follow any particular pattern, but an easy way to take action with interleaving is to have three books at all times.

Switch from book one to book two and then book three on a loose pattern.

Don’t “try” to recall different elements or connect them. Just plow forward and enjoy the benefits of what your mind will do for you on autopilot.

This is one simple strategy where the “let go of the outcome” attitude is really important.

Four: Use Your HandsWe often hear about different note taking and mind mapping techniques.

Although neither of them are the best way to study and memorize, they’re great because of how they get the hands involved.

But scientists have shown that the deliberate use of gestures helps you learn.

You can also use your fingers to learn different ideas.

For example, take an example of abstract thinking you want to learn.

Name the concept out loudPress your thumb and pointer finger togetherFocus on mentally “linking” the idea to the connection between thumb and fingerTake 2-3 deep breaths as you focusRevisit the connection throughout the dayThis simple technique can be used in combination with gestures.

True, it’s hard to imagine how it will scale to help you remember dozens of ideas. But give it a try. If you can make it work for one idea, you can reuse the technique to help you remember dozens.

I used to struggle to understand charts and graphs. This is because I’m easily overwhelmed by too much information displayed on a page that isn’t text.

Then Tony Buzan gave me the idea of re-drawing those charts and graphs with my own hand.

While taking a few minutes to manually reproduce information charted out visually, I was able to explain to myself their meaning.

I’ve since used this technique to help me remember harder vocabulary in various languages that other memory techniques for some reason could not penetrate.

Six: VerbalizeWhen I was struggling to understand various aspects of French philosophy, I read it out loud.

Back then, iPhones were still a daydream. I recorded myself reading into a micro-cassette recorder.

Then, I would listen back to the recording while reading the book.

You might think, “That sounds time-consuming!”

It isn’t.If you’re spending time reading and failing to comprehend the material, that’s 100% consuming time you

cannot get back.

But narrating material and then listening back to it in a way that captivates your mind so information can integrate into memory?

That’s just smart learning.

People love their spaced-repetition apps.

Yet, so many fail to show positive results despite spending hundreds of hours using them.

Worse, they might be able to answer correctly on the app. But in the real world?

No such luck.

This is because spaced-repetition must involve active recall in order to be truly effective.

To get more out of each and every card or slide in your app, do this:

Add multisensory associations to the informationNever show yourself the answer until you’ve tried to recall the information through associationBe suspicious of the answers you give the app (in other words, be honest)Recall information even when the app isn’t asking you to learnFor example, let’s say you’ve got a list of medical terms.

Rather than have “edema” on one side of the card and the definition of the other, try this:

Imagine a famous person named Ed and an emu or someone named Emma swelling up with fluid. Hear the sound of them stretching. Feel it physically, as if it were your own body. Imagine the emotions involved and focus on what the situation would look like.

You might even write out this scenario on the card instead of the word or the definition. When you try to recall the word, treating it like a puzzle to solve will help your brain create connections.

A faster and more physical way to do this is by using physical index cards. Learn more by reading my how to memorize a textbook post.

One of the quickest wins of all is to keep moving.

The best part is that moving from spot to spot while you’re studying not only helps your memory. It’s an easy way to incorporate taking breaks and getting a bit of physical fitness.

There are at least three ways to approach this principle:

In your homeOn campusAround townWhile at home, pick 2-3 locations you can tackle your study materials. For example, your room, the kitchen table and the back porch. Deliberately switch things up over twenty minutes or so.

On campus, have a few different spots in the library. Move to a cafe and look for empty lecture halls or classrooms you can park in to read a chapter or two.

Now that I have a Ph.d., I don’t have the benefit of a campus anymore. But I still cart my books around with me for my current research projects. I read at the beach, in front of stores while my wife is shopping, on the bus, etc.

Nine: Use Those LocationsAlthough it’s beneficial to move around, you can get even more bang for your buck by turning those locations into Memory Palaces.

This technique is more robust and will take at least a weekend to learn thoroughly.

To use it, turn any location into a mental reference tool.

If one of your study spots is the kitchen, use the walls to create associations and hold in place.

For example, instead of placing the “edema” example we used before on a card in SRS software, you can mentally project it onto a wall.

There are a few ins-and-outs to learn, so if you’d like more info, please grab my FREE Memory Improvement Kit:

Ten: Make It A GameA lot of learning apps try to “gamify” the learning process.

I think they’re heading in the right direction.

However, I think they’re missing a piece of the puzzle.

It relates to the mindset issue we mentioned at the beginning.

Anything can be a game if you simply decide to make it one.

And the best games we play are the ones we design ourselves.

My personal philosophy around the best designed games is simple:

Only play the games that you are happy and willing to play again and again.

Voluntarily.

At the end of the day, those kinds of games are easy for me to define:

They involve tons of variety and plenty of options for flexibility and personalization.

As for rewards, sure. They can be useful.

But for the best possible results, make playing the game itself a reward. Not even the toughest topics will ever seem boring to you again.

If you’re still asking that question, chances are you haven’t turned learning into a game you can win.

So to sum up:

Work on your mindsetTake breaks properlyUse interleavingGet your hands involved in multiple waysCopy hard graphs you cannot understandVerbalize and recordUse spaced-repetition correctlyChange your location frequentlyMaximize the locations by using the Memory Palace techniqueMake learning a gameEven if you pick just 2-3 of these tips and get started with them, your ability to remember what you study will quickly soar.

So what do you say?

Are you ready to get more out of your study sessions? This set of tips truly is the best way to study and remember fast.

Let me know in the comments and enjoy the blessings of knowledge!

March 3, 2022

The Surprising Difference Between Philosophy and Psychology

Although philosophy and psychology have always been intertwined, the surprising difference you’re about to discover is incredibly valuable to understand.

Although philosophy and psychology have always been intertwined, the surprising difference you’re about to discover is incredibly valuable to understand.

You see, there are a lot of simplistic discussions about philosophy vs psychology.

For example, some people will say things like:

Philosophy studies wisdom while psychology studies the soulPhilosophy and psychology both study humans and how they behaveWhereas philosophy leads to one set of career options, psychology leads to anotherPsychology can observe behavior in laboratory settings, but philosophy cannotAlthough there is some truth to some of those statements, frankly, they’re all missing the most important point.

So if you’re a lifelong learner and ready to solve the riddle, let’s dive in.

What’s the Difference Between Philosophy and Psychology? 4 Things to KnowBoth philosophy and psychology are rich fields that involve many branches. Arguably, philosophy gave birth to psychology, and there’s a simple way to demonstrate why this is true.

Let’s look at this simple fact first and then explore other things you need to know about the differences between these two fields.

One: Philosophy Is What We Use When We Don’t Have A ScienceTechnically speaking, psychology is a science. There are many kinds of psychological sciences, ranging from cognitive neuroscience to the study of personality, forensic psychology and more.

In order to study aspects of the human mind related to cognition, performance at work, development from childhood into adulthood, etc, psychologists use tools of observation, measurement, analysis and scientific writing.

But when we have questions about the nature of existence for which no such scientific tools exist, we use philosophy. This is not to say that philosophy cannot be scientific. Much of the best philosophy draws upon all the science the philosophy has on hand.

However, it would be ridiculous to say that anyone has tools to measure concepts like infinity.

Yet, we still manage to think about the infinite in a variety of ways despite not having a science of infinity. You don’t even have to understand mathematics particularly well to arrive at certain conclusions about this aspect of reality. This is why philosophy is important.

When I say that philosophy gave birth to psychology, I am pointing to the fact that most of our records show that philosophy predates psychology. People seem to have been asking questions about the nature of reality somewhat before they were asking about the nature of the mind.

Two: Philosophy Combats Confusion, Psychology Creates ItThis point might have you scratching your head.

Why on earth would psychology create confusion?

It absolutely does because it is a science.

Science is a tool that allows us to ask hypothetical questions and then produce evidence that either confirms or denies our hypotheses.

There’s going to be confusion along the way any time science is correctly performed.

Philosophy, on the other hand, looks at confusing data or stimuli and tries to make sense of it. Indeed, this is precisely why we have the philosophy of science.

Because philosophy is concerned with truths about reality and science is concerned with providing evidence that helps clarify the validity of our questions, this difference between the two fields is essential. Science is much more concerned with validation than it is with truth, and that is why science must constantly test and retest.

And make no mistake. If you thought that science was about truth, this is simply not the case. In fact, there is something called the reproducibility crisis. An extraordinary number of studies that scientists have assumed give us an accurate picture of the world do not work when other scientists try to produce the same results.

If we did not have philosophy to try and help us figure this out, we would be in big trouble indeed.

Three: Philosophy Has Multiple Methods, But Science Boils Down To Just OneAlthough science is of course incredibly complex, it ultimately has just one method: the scientific method, or empiricism. Our claims are valid when they can be reproduced.

There are a lot of ins-and-outs to the scientific method, such as falsifiability. This is an important principle, so please look into it.

Philosophy, on the other hand, does not rely on falsifiability. It might refer to it, but more often than not, philosophers rotate problems through a variety of philosophical methods. For example, an individual philosophy might look at a given problem through the lenses of:

Ontology and metaphysicsEpistemology Related fields like psychoanalysis, economics, sociology and other disciplinesIndeed, a philosopher does not need to be a Marxist (or even a Marxoid) in order to benefit from wondering how such a person would try to solve a particular problem.

Likewise, a philosopher can provide incredibly useful ways of looking at things by simply wondering how a psychoanalyst would answer a question that has arisen either personally, regionally or on the world stage.

One problem we face in today’s world is that many scientists now use social media to share their views. Many people take those views to be scientifically valid because they are coming from scientists.

Doing so causes us a lot of heartache because those scientists are in fact being philosophical. But when you know the definition of philosophy, you know it’s possible to be philosophical without actually being a trained philosopher.

As a result, often their philosophical views are much weaker than they would be if they had as many methods as a trained philosopher typically uses.

Four: Philosophy Broadens And Deepens, Psychology Explains How That’s PossibleAlthough there is a field called philosophy of mind, often it tries to account for differences between mind and matter. It is highly speculative about where the mind ends and matter begins and vice versa.

But overall, philosophy’s main role is to help us broaden and deepen our understanding of reality, truth and answer the hard questions for which no science yet exists that can help us. As soon as a science emerges, philosophy tends to let it do its work and then help make sense of the data.

What makes psychology so exciting is how it works to tell us how it’s possible for the three pounds of brain matter in our skulls to produce philosophical thoughts in the first place. Psychology is literally the psychological study of how the many parts of this one organ called the brain collaborate together to create the experiences of thinking, using language to communicate and complete goals in competitive environments.

Certainly, philosophers have done a lot to help us learn how to cope with adversity. But psychology, not philosophy, is behind the development of pharmaceuticals. Many of them have been incredibly helpful for people around the world. And when ethical issues arise, philosophy is there to help us work out what is right.

Psychology vs. Philosophy: How Are They They Same?As we’ve seen, there are several critical differences that make philosophy and psychology very different.

Yet, there is at least one way that they are the same:

They both combine many sub-disciplines.

They are also able to work together.

And the surprise ending I’ve been leading us toward all along?

It is this:

These days, you really cannot be a philosopher without understanding as much about psychology as you possibly can.

One would hope that psychologists would also be guided by philosophy, particularly in the realm of ethics. But let’s call a spade a spade. It is in no particular way necessary to know about philosophy in order to engage in psychology. Sadly, many people aren’t even aware of what philosophy really is.

But philosophers must be aware of psychology and that is because philosophy deals with the nature of reality. Science has evolved to become a very key part of reality indeed, and its importance is only growing.

In order to ensure that psychology helps humanity flourish and doesn’t drown it in psychiatric pills or what Jerry Muller calls the Tyranny of Metrics, it’s imperative that we all practice philosophy at its highest level.

This means that we must practice free inquiry. We must keep our critical thinking skills sharp. We must be able to reflect deeply on how psychology affects our individual experiences and our global culture.

The ability of philosophy to help make sense of what psychology tells us about the human brain and how it produces our experience of mind should never nudge psychology out of the way.

Rather, we must use our philosophical skills to help us understand what is empirically justified in psychology. And as philosophy continues to evolve, we as sophisticated philosophers must recognize the limits of philosophy when it cannot be empirically justified.

When well-used, philosophy’s many methods bolster psychology’s main scientific method. And at the end of the day, the earliest philosophy on record points us to precisely this quest.

As discussed in A Companion to African Philosophy, the Ancient Egyptian philosophers talked about tep-heseb, or the “correct method.” They believed that correct thinking was possible. In other words, that thinking can and should be correct.

In that regard, our best philosophers and psychologists of today surely agree.

And if you’d like to remember everything we discussed today, please consider grabbing my FREE Memory Improvement Kit:

I have combined the best of the philosophy of memory and the psychology of memory in this program to help you learn faster and remember more.

So what do you say?

Is the difference between psychology and philosophy clearer to you now?

I hope you can see that we don’t have to think in terms of psychology vs philosophy. Although they cannot be evenly weighted in any meaningful way, as the Ancient Egyptians indicated, they can be combined in ways that support “correct thinking” for one and all.

February 23, 2022

The 15 Main Thought Processes and How to Improve Them

Wouldn’t it be great if there was an ultimate list of thought processes?

Wouldn’t it be great if there was an ultimate list of thought processes?

A definitive resource you could bookmark and refer to whenever you want to sharpen your thinking?

I thought so too, and that’s why I decided to create one.

Who am I to care so much about thought processes and talk about them in-depth?

Well, I taught an advanced critical thinking course for years at a university.

And I personally practice many types of thought as I continue to absorb many philosophical traditions from around the globe.

So if you want multiple thought process examples and sure fire ways to improve your thinking, let’s dig in.

What Are Thought Processes?According to researchers, a thought process can be both conscious and unconscious. In fact, your mind can be processing more than one thought at the same time.

For this reason, the exact definition of a thought process is simple:

It is being engaged with the stuff of thought.

The fact that many of your thoughts are outside of your awareness is cause for concern. Although many positive types of thought process stimulate our creativity and problem-solving capacities, Daniel Kahneman’s work has shown us to be at the mercy of many cognitive biases.

Cognitive bias is any of a wide number of thought processes that cause us to take shortcuts. We distort reality and make irrational decisions as a result.

For this reason, it’s a very good idea to become familiar with as many thought processes as possible.

Types of Thought Processes (with Examples)As an exercise, don’t just read the following list passively. Try to think of a time you’ve either thought these ways yourself, or observed others involved in these thinking processes.

For best results, write your personal examples and observations down.

Also, reflect on whether or not each thought process is positive, negative, neutral or more than one of these options at the same time.

One: Associative ThinkingBeing able to see how one thing connects to another is an important skill. In healthy children, the ability to think in terms of association begins early. Most of us get better at it as we age because more life experiences creates pattern recognition.

For example, we often relate things we see in life to mythological patterns. You might associate someone with King Midas if they’re greedy, or say that a Pandora’s box has been opened. These are kinds of associative thinking stimulated by pattern recognition.

It doesn’t have to be Greek myths either. Since 1999, it’s been very common for people to respond to certain events in the age of the Internet by saying, “It’s just like in The Matrix.”

Freud famously asked his patients to engaging in free association, leading to many new psychological therapies and procedures, such as the Rorshach test.

And association is widely used. Creative people frequently allow themselves to follow random trains of thought in order to come up with interesting and unique ideas. Students use mind mapping and association is a key mnemonic strategy.

Two: Abductive ThinkingThis form of thinking involves drawing conclusions based on observations. It is also called inferential reasoning and Sherlock Holmes provides the most well-known examples. Real life detectives use it as well.

A simple way to think about this thought process is that you’re arriving at a conclusion without having the full picture. If you arrive at a crime scene and find a knife covered in blood, you can reasonably conclude that it is the murder weapon. But you don’t actually know – you’re inducing the conclusion.

Note that many people mistake this kind of reasoning with deductive thinking. So let’s look at that next.

Three: Deductive ThinkingDeductive thinking is often formulaic. It usually involves an “if this then that” structure. For example, you can deduce that if you don’t get on the freeway before rush hour, it will take you longer to get home.

Unlike induction where you are drawing a conclusion from an incomplete picture, you do have a complete picture of how traffic works on the highway.

Deductive reasoning is typically easier to test when there is an abundance of evidence. There are three main types to master:

SyllogismsModus ponensModus tollensTo help yourself further, check out these critical thinking book recommendations.

Combined, inductive and deductive thinking form what we tend to think of as logical or rational thinking.

Four: Social ThinkingWe tend to think of ourselves as individuals.

Nothing could be further from the truth!

Humans share a variety of languages, and when you think about it, none of the words or phrases belong to any individual. Rather, we collaborate on the continuous evolution of this communication tool.

We’re increasingly using the Internet to communicate using our languages as well. Students use it to study together, which means thinking together to help one another achieve goals.

We can also think about transpersonal thinking in this regard. When we realize that the role of the individual isn’t all that it’s made out to be, we’re able to transcend the ego and resolve ourselves into the great river of life.

Sound abstract? Never fear. We’ll be tackling that kind of thinking next.

Five: Abstract ThinkingTo think abstractly is to literally pull away from an idea or concept.

We just did that by thinking about how language is not owned by any individual person, even if it is experienced in personal ways.

This is an “abstract” thought precisely because we’re pulling back from the individual and looking at the entire species.

This is a nuanced thought process, so you can read more about abstract thinking with other examples if you’re interested.

Six: Concrete ThinkingConcrete thinking involves ideas that are directly related to material reality. For example, you might think about how things feel and make comparisons and contrasts in your mind.

An orange and an apple feel more similar to one another than an orange and the handle of a shovel, for example.

Talking about rain “pounding” is another example.

Seven: Analogical ThinkingAnalogical thinking involves making comparisons and assuming that when something is true for one thing, it is also true for the other.

We can use them well, such as when we say that an argument is going in circles. If the same points keep coming up again and again, they really do feel like they are on a loop.

But analogies often fall apart because things are rarely as similar as they seem. Watch out anytime you hear someone saying, “it’s like x.” Although the comparison they are about to make sense on the surface, all too often the connection winds up being facile.

Eight: Analytical ThinkingAnalysis literally involves taking things apart.

For example, when a Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass participant comes to me with a problem they’re trying to solve, I analyze what they’re saying by looking for the individual components.

That’s not to say I don’t also take the problem as a “whole.” Rather, analytical thinking takes as a basic premise that everything is built from parts.

In philosophy, the notion of deconstruction is an analytical process that reveals how many of our most cherished truths were built over time. It is an innovation on what Nietzsche called genealogical thinking.

A simple way to get better at this form of thinking is to practice observation and questioning literally everything.

Nine: Linear ThinkingLinear thinking is all about structure and following a particular process.

But that doesn’t make it boring.

In fact, Triz is one of the most interesting collection of tools for linear thinking on the planet. It’s also incredibly inventive.

Nonlinear thinkers are sometimes thought to use fewer structures, or purposefully introduce randomness.

For example, the German band Einstürzende Neubauten create new songs by drawing ideas and roles from a hat. Although the singer might not be a world class drummer, if he selects a slip that requires him to play percussion while composing a new song, he will.

Although this form of creativity looks like it is nonlinear and “outside the box,” it’s also procedural and linear in its own way. If we “deconstruct” the notion of linear thinking by using analytical thinking, we might find that there really is no such thing as nonlinear thinking at the end of the day.

Ten: Reflective ThinkingMaking time to contemplate is incredibly important.

It’s simple and easy to practice and there are many powerful reflective thinkers you can draw inspiration from.

Simply put, find a place to sit, pour your thoughts out onto paper and use analytical thinking to sort, sift and screen through the material of your mind.

It’s perfect for helping yourself make better decisions and expand your mind.

Eleven: Counterfactual ThinkingWe often think of alternative histories as the stuff of fiction. Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle is a common example.

However, it’s very useful to think about what could have happened in our everyday lives.

For example, sometimes when I’m feeling down, I create a “counterfactual” image of what my life would be like if I’d never completed my Ph.d.

I happen to know a few people who didn’t finish. The thought of working at an ice cream parlor like one failed PhD I know makes me grateful for everything in my life – especially because the accomplishment led to me writing this blog.

Let’s look at the opposite of this kind of thinking next. It’s also very useful.

Twelve: Speculative ThinkingIf counterfactual thinking involves imagining alternative scenarios in the past, speculative thinking involves running through two or more possible future outcomes.

One simple exercise for thinking through your future is Dan Sullivan’s “dangers, opportunities, strengths” routine.

By asking yourself questions around these three core areas, you can imagine a practical path forward for your future.

You can also use the journaling exercise I share in this video about how to think correctly about the path to mastering your memory:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5k7ho...

Thirteen: Decisive ThinkingWhen it comes to the future, you’ll never get there without being able to make decisions.

One of my favorite problem solving models is found in Decisive by Dan and Chip Heath. It’s called the W.R.A.P. technique:

Widen your optionsReality testAttain distancePrepare to failUsing step-by-step decision processes like this can always be considered “heuristic thinking,” because you’re making using the tool a rule of thumb.

I’ve connected this technique with a much older tool called ars combinatoria that you might want to become acquainted with on your quest to master multiple thought processes.

Fourteen: MetacognitionEver heard of Zen?

It’s a fairly radical philosophy that helps you realize that the present moment is all we really have – and since it’s slipping by so quickly, the notion that we have it at all is an illusion.

In order to realize this fact and hold onto the realization so that you can experience lasting mental peace, the great masters of meditation use metacognition.

To become a master yourself, you just need to cultivate an awareness of the operation of your own thoughts and a meta-level awareness of how the thoughts about your thoughts operate too.

I’m a big fan of this form of thinking and wrote about a powerful process in my book, The Victorious Mind.

You could also call this form of thinking, “mindfulness thinking.”

Fifteen: Skeptical ThinkingI’ve saved the most important form of thinking for the end. And I want you to use it on everything I’ve just said.

Why?

Because one of the most powerful things you can do is to question the validity of the claims people make.

Think for yourself.

Do your own research.

Test.

If you don’t, you risk being naive.

Of course, you don’t want to go overboard. It’s also useful to be curious and allow certain things the benefit of the doubt from time to time.

This is where you want to use your discernment, which is where practicing all of the skills on this page will really come in handy over time.

How to Improve Your ThinkingThe best way to experience significant gains in your thinking abilities is to complete critical thinking exercises.

On top of that, you’ll want to improve your:

Reading strategiesReading comprehensionVisualization skillsMemory Palace skillsBut above all, you want to set aside time for studying great thinkers and time for practicing thinking.

It just takes commitment and consistency.

And the best part?

You now have new ways to think about how you might increase your commitment and consistency by using tools like analytical thinking and speculative thinking to become the architect of your future.

So what do you say?

Are you ready to enjoy multiple types of thought?

Dive in!

February 17, 2022

What Is Philosophy? A Life Changing Answer

A major problem with philosophy is that just about every philosopher has a different definition of what they do as a philosopher.

A major problem with philosophy is that just about every philosopher has a different definition of what they do as a philosopher.

This is sad because it turns a lot of people off who would otherwise benefit tremendously from exploring the art, science and craft of philosophy.

So let’s simplify things by looking at the two ways philosophers define the field first.

Descriptive (what philosophy is) Prescriptive (what philosophy should be)Once we realize that people rotate between these two categories of definition, everything will become much clearer.

Ready?

Let’s dive deeper into the wonderful realm of philosophy!

What Is Philosophy? The Simple AnswerThe most direct philosophy definition I’ve ever seen is that philosophy tries to make sense of existence. And more than merely make sense of it, know that the sense we make is true, or at least accurate. Typically, this is done through the use of reason, though there are many other philosophical tools.

Now, you might be wondering…

Why doesn’t science take all of this up?

The problem is that science is a tool that helps us gather evidence to validate or invalidate our ideas about the world. But existence itself? We don’t even know what being is or have the tools needed to study whatever existence is. And until we do, we’ll need philosophy.

Now, within existence, we find many ideas, concepts, people and objects. They all seem to exist in different ways. Yet, they are bound by a major similarity. They exist.

Philosophy tries to figure out the what, why and how of existence, or what some philosophers call Being with a capital B. Then, they work on figuring out what that knowledge about being tells us about how we should live in the world.

Now, because existence is quite complex, philosophy has split up into many different types and categories. We’ll talk about several of these in a moment.

But I mentioned above that many philosophers talk about what philosophy should be by way of defining it.

An Alternative Philosophy DefinitionOne classic example is found in What is Philosophy? By Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. They say that philosophy should be the creation of concepts.

This is a prescriptive definition rather than the descriptive one I gave above.

The book gives examples that show how philosophers define philosophy only by creating concepts. Plato created the concept of the Idea which later influenced Descartes’ notion of cogito.

In this way of thinking, philosophy is something that influences the production of conceptual responses to previous ways of doing philosophy.

You could then say that philosophy is almost like a living thing, evolving along with the human species. This co-evolution is just one of many reasons why philosophy is so important.

And here’s the point:

If philosophy is subject to evolution, then we should do all we can to help it evolve in a positive way.

What Philosophy Is NotWhat does philosophy mean?

Another way to get at the answer is to look at what philosophy isn’t. And that means looking at people who pretend to be philosophical, but aren’t.

In a work of philosophy called The Sophist by Plato, we find three key definitions of the kind of person who fails to hit the mark of creating new concepts and properly answering the questions of existence.

First, Plato points out that many people sound philosophical when in fact they’re just playing around with words. If you’ve done any amount of reflective thinking in your life, you might have wound up doing a bit of wordsmithing yourself, as have I. But that doesn’t mean what we came up with was properly analytical.

Second, Plato noticed that Sophists used tools of persuasion to win arguments. These people weren’t really concerned with the truth about existence. They just wanted to come out on top in the discussion. As a result, technique was more important to them than accuracy.

Finally, Plato felt that these people who only appeared to be doing philosophy lacked modesty. Rather than admit or even seek the limits of their knowledge, they pretended to know-it-all. Doing so is inherently un-philosophical.

With these counter-examples in mind, we can say that to be properly philosophical, you need to:

Use clear language, or at least use language for the goal of creating clarityDon’t switch your analytical tools and rhetorical style just to win an argumentBe humble and remain conscious of the limits to your present understandingAs a result, as you use philosophical thinking to pursue the truth, you will truly expand your mind.

Philosophy Throughout Time And PlaceUnfortunately, it’s all too common for people to think only of philosophy in terms of specific times and places.

For example, some people focus exclusively on Continental Philosophy or only Ancient Greek Philosophy.

But as Bryan van Norden points out in his book, Taking Back Philosophy, many cultures have used philosophy to determine what existence is and use that knowledge to decide how best to live in the world.

The more you know about philosophy throughout the ages and around the globe, the better you’ll be able to formulate your own concepts as Deleuze and Guattari say that we should.

Styles of PhilosophyOne of the things that makes philosophy exciting is that it comes in many different styles.

Philosophers like Plato, Hume, Bruno and many more wrote dialogs, for example. While reading them, you can imagine various characters working through the ideas.

Other books might use aphorisms or use language in ways that illustrate the point the author is trying to make.

For example, one of Friedrich Nietzsche’s points was there really aren’t any truly coherent philosophical systems. He used puns, poems and an aphoristic style to drive home the point. He also made his philosophy visually resemble the surviving fragments of the Pre-Socratic philosophers he so admired.

Likewise, Jacques Derrida explained his theories of deconstruction, the metaphysics of presence and the trace by writing in ways that showed them in action. In other words, he wasn’t merely talking about the concepts. He was doing them.

Although this frustrated many readers, Derrida was engaged in exactly what Deleuze and Gauttarri claim philosophers must do: invent concepts.

The 11 Subfields of Philosophy (And Why They’re Important)I mentioned that philosophy is subdivided in many ways.

Let’s look at some of the most important.

One: LogicLogic can be defined in a few ways.

First, it can refer to a particular form of argumentation. Thinking logically can help you solve problems through discussion with others, or even on your own.

Logic is also about the best possible forms of inference. As Graham Priest puts it, the norms around how we use inference change over time. There are rival theories that compete with one another over what is the exact best ways to use logic.

Two: MetaphysicsTa meta ta physica literally means “the ones after the ones about physics.”

When Aristotle used this term to differentiate his work on physics, he was referring to the fact that humans have things to discuss for which there is no scientific process.

Whereas it is possible to think concretely about many aspects of the world, topics like being require abstract thinking. Thus, we can think of metaphysics as a kind of mental activity more than a science. It is a means of trying to make sense of things that science cannot yet account for.

Another way of thinking about metaphysics is that it is a means of working out what is real. For example, if you’ve ever tried to work out whether or not infinity is possible, you’ve engaged in metaphysical thinking. No one can physically hold infinity in the palm of their hand, so we’re forced to think about it abstractly and without the benefit of physical evidence that we can examine.

Three: EthicsEthics is a branch of philosophy that helps us define and improve our moral principles. Whereas some thinkers believe that morality is subjective, others believe that it is objective.

The difference matters because if people are free to believe that the definition of morality is up to them, they might make hideous decisions. But if there is a concrete means of determining what truly does lead to the most good for the most people, we can consider our obligations around implementing laws that help produce such good for the majority.

Jeremy Bentham’s felicific calculus was one interesting attempt at working out a way of measuring pleasure and happiness to help determine the moral status of different human activities.

This type of philosophy focuses on the nature of knowledge. What does it mean to know things? What kinds of things can be known? And how do we know that we know them?

Epistemology looks at the limits of knowledge as well, and can be tremendously humbling.

Five: Philosophy of MindPhilosophy of mind brings together many other fields. As William Jaworski puts it, the field brings together five areas of study together with metaphysics and epistemology:

Mind and bodyConsciousnessMental representationPsychology and neuroscienceAction theoryIn this field, there tend to be two styles: monism and dualism. Whereas monism posits that there’s only one kind of thing that makes up our being, dualists argue that there are at least two kinds of properties. Monists suggest that everything is ultimately mental and dualists think there is at least the mind and the physical, material world, perhaps more.

There’s nothing particularly new about this argument. Ancient Indian philosophy, particularly Advaita Vedanta, features many discussions about monism vs. dualism.

Is it the job of science to arrive at the truth?

Some people say yes. Others, like myself, argue that science is merely a tool that helps us validate ideas and what counts as truth is always contingent. We can always run our experiments again and produce new data that may change the conclusions science has helped us produce.

Some people have created terms for these two different philosophies of science. As James Ladyman puts it in his book, Understanding Philosophy of Science:

“Scientific realism is the view that we should believe in the likes of electrons, whereas scientific antirealism is the view that we should stop believing in the truth of scientific theories and content ourselves with believing what they say about what we can observe.”

Personally, I don’t think of myself as an anti-realist whatsoever. In fact, I’m very much a Realist, even if a quirky one.

But I don’t think Ladyman means anything negative by using this term. What is a philosophy of science like mine best called? I would perhaps call it Scientific Contingency Realism. Such a term helps reflect the positive choice to acknowledge that science can always produce new data that always has at least the potential to change what we thought was once true.

Seven: Political PhilosophyWhen I started university, I was in Political Science. I read Plato’s Republic and had a career as a politician in mind.

However, I quickly needed to pivot into English Literature in my second year. After interviewing a politician for the school newspaper, I quickly realized that he was a tyrant. I worried that if I continued, I would become one too.

Why is this a problem?

Because political philosophy is a risky business. It’s all about the difference between political ideals and the way the world really works. As Joseph Chan puts it in Confucian Perfectionism, political philosophy almost always has an ideal in mind because:

“Any form of political theorizing that lacks an ideal is like a ship embarking on a voyage without a destination, and political theorizing that is insensitive to the constraints of reality is like a ship on rough seas without competent navigation.”

Can you see the problem here?

We don’t actually know what reality is. That’s why we still have philosophy in the first place.

Yet, politicians are that unique breed of person who thinks reality has been understood and that’s another reason I needed to get out of the Political Science program immediately. In some ways, political philosophy makes too many assumptions to really be considered a philosophy at all.

(Note: No shade to Chan, by the way. It’s a good book and he readily admits that his definition is bound to be controversial.)

Eight: Legal PhilosophyLegal philosophy has more redeeming value in my mind. This is because the law is used to help restrain and correct the overreach of the politicians.

As Matthew Kramer shows in What is Legal Philosophy?, determining what counts as evidence in a trial requires a theory of knowledge or epistemology. There are also many moral dimensions to be considered that science cannot yet answer.

Nine: Business PhilosophyBusinesses face many issues, from ethics to what you might call a philosophy of performance.

How do you keep morale high? How do you respond to mistakes? What’s right and wrong with respect to the bottom line and how do you know?

In many cases, the science of business can tell you a lot about what’s going to be the most profitable way to answer those questions. But focusing on profit doesn’t always lead to longevity in the market.

Ten: Personal PhilosophyIn many ways, each of us are like mini-businesses. Or at least, we’re all like entrepreneurs.

Even if you don’t have a business, you invest in your health, your education, your psychological well-being. And whenever you invest, you’re expecting a return.

Many philosophical questions arise as a result. And as Nietzsche reminds us, there’s a lot of truth out there. But we don’t always know when it’s a good idea to act just because we know that something is true. On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense goes through such issues.

To craft your own personal philosophy can be quite a challenge. That’s why I’ve been working on something to help you.

Eleven: Philosophy of MemoryI’ve often argued that the quality of our lives is directly linked to the quality of our memory abilities. After all, the ways that we act in the world rely on what we can recall on demand when we need to act or make decisions.

Even our ability to ride a bicycle well relies on the strength of our procedural memory.

To this end, I’ve started a new book, my most challenging book yet. You can get a sample chapter called The Primacy Effect if you’d like.

Part of the concept of a philosophy of memory I’m creating suggests that we need a personal philosophy of performance that exercises our memory holistically.