Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 243

March 22, 2014

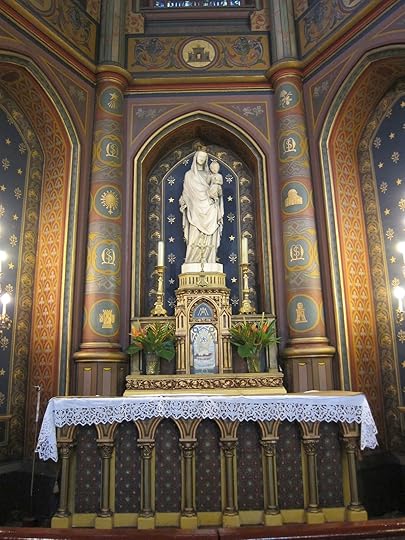

Sunday Mass with the Cardinal Archbishop of Paris

Last Sunday we were in Paris and attended Mass in the Extraordinary Form of the Latin Liturgy of the Roman Rite at St. Eugene-Sainte Cecile--and so did the Cardinal Archbishop of Paris, Andre Vingt-Trois. He was visiting the parish and had said the 9:45 a.m. Ordinary Form Mass. The 11:00 a.m. Extraordinary Form Mass was a Solemn High Mass with two deacons assisting the pastor. The Archbishop gave the homily for the Transfiguration Mass of the second Sunday of Lent.

St. Eugene-Ste. Cecile has offered Mass in both the Missal of 1962 (Extraordinary Form) and the Missal of 1969 (Ordinary Form) since 1984--it is "Une paroisse en deux liturgies". As we noted in 2012 when we attended the 11 a.m. Mass, the congregation is large and is a good mixture of young and old.

The outstanding Schola Sainte Cecile honored the presence of the Cardinal Archibishop with a rousing chorus of "Ad Multos Annos" after the pastor made his announcements before the conclusion of Mass. Throughout the liturgy, they sang some beautiful hymns and the Ordinary parts of the Mass. They provide copies of the programme for the Mass and of hymns to be used throughout "Careme". You can hear excerpts of their music and even the entire Mass here. Their diligence and devotion to the music for the 11:00 a.m. Mass for each Sunday is magnificently demonstrated on their blog. During our experience of the Mass, one of the sensory highlights was the choir chanting "O Salutoris Hostia" immediately following the Consecration. The processional hymn was Audi benigne Conditor; during the Offertory we sang Christe qui lux es et dies, and the recessional hymn was Attende Domine.

After Mass, we took a few pictures (my husband used both his Fuji X-100 Rangefinder and his Canon S-100):

Published on March 22, 2014 22:30

March 21, 2014

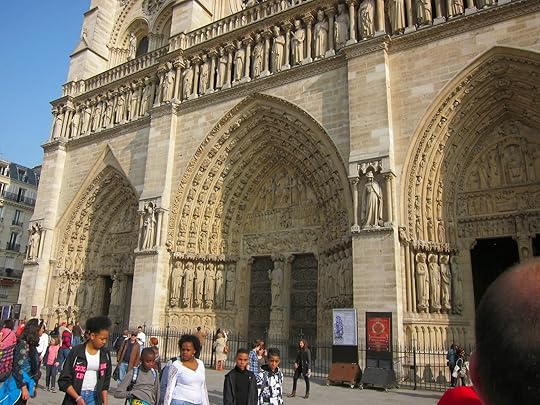

Report on the Veneration of "La Sainte Couronne d'Epines" at Notre Dame

As I had planned, I did attend the Veneration of the Crown of Thorns at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris last Friday. I rode the free Metro from the station near our apartment to Bastille on Line 8 and transferred to Line 1 for Hotel de Ville. Walking across that parvis, I crossed over the Seine to the Ile de la Cite! I was so happy to see the facade of that great church, with all the crowds gathered in front of it, and the queue for entry moved quickly. I was a little late and came into the service about 10 minutes after it started. Lots of walking up and down stairs transferring from line 8 to line 1 in that Bastille station!

The Chevaliers du Saint Sepulcre a Notre Dame de Terre sainte served as ushers for the service while the organist and a cantor led the congregation in psalms and hymns. The gentlemen of the order were resplendent in long white capes and white gloves, while the ladies wore long black capes and gorgeous black lace mantillas. They were quite busy seating latecomers like me and shooing away tourists and photographers. Between the hymns and psalms, which included Bishop Fortunatus' Vexilla Regis and the Ave Regina Caelorum, a priest gave reflections on the theme "Tout est accompli"--It is finished, one of Jesus' Seven Words from the Cross.

Other ladies carried baskets with prayer cards. Eventually, the section I was seated in joined the procession for veneration. Many in the congregation left immediately after veneration, but I stayed through the end, when the Crown was carried in procession out of the nave. The Chevalier who served as thurifer perfumed the air down the aisle with huge swings of incense. It was a very moving and solemn service.

Published on March 21, 2014 22:30

March 20, 2014

Josephine at the Musee du Luxembourg

I apologize for the lack of blogging since last Friday, but somewhere over North America or the Atlantic Ocean, my little netbook malfunctioned--it worked fine Thursday morning, March 13, but wouldn't locate my profile when we arrived in our rented Paris apartment Friday morning, March 14! On Saturday, March 15, we made use of the free Metro (more about that in another post) to attend this exhibition on the life and times of Josephine Bonaparte at the Musee du Luxembourg, described here by parisvoice.com: One of France's most remarkable First Ladies, Josephine, is the subject of an exhibition at Paris' Musée du Luxembourg. On the occasion of the bicentenary of her death at Malmaison in 1814, the exhibition revisits through paintings and many personal items Josephine's life and times.

I apologize for the lack of blogging since last Friday, but somewhere over North America or the Atlantic Ocean, my little netbook malfunctioned--it worked fine Thursday morning, March 13, but wouldn't locate my profile when we arrived in our rented Paris apartment Friday morning, March 14! On Saturday, March 15, we made use of the free Metro (more about that in another post) to attend this exhibition on the life and times of Josephine Bonaparte at the Musee du Luxembourg, described here by parisvoice.com: One of France's most remarkable First Ladies, Josephine, is the subject of an exhibition at Paris' Musée du Luxembourg. On the occasion of the bicentenary of her death at Malmaison in 1814, the exhibition revisits through paintings and many personal items Josephine's life and times.Josephine de Beauharnais was the first wife of Napoleon I, which made her the first Empress of France. She was born in Martinique and married at sixteen to Viscount Alexandre de Beauharnais. These were tumultuous times for France. During the Revolution's Reign of Terror she was thrown into prison along with her husband who was guillotined. She narrowly escaped death owing to Robespierrre's timely fall.

Bonaparte, then only a twenty-six-year-old general, fell for her charms and married her in 1792, less than five months after their first meeting. She rose up with him as wife of the First Consul after the coup d'etat of 18 Brumaire (1799). She became the first Empress of France, crowned by Napoleon in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris (1804).

She did not bear Napoleon any children; as a result, he divorced her in 1810 to marry Marie Louise of Austria. She withdrew to Malmaison where she pursued her interests in the arts and gardening, most notably cultivating and hybridizing roses. Through her daughter, Hortense, she was the maternal grandmother of Napoléon III.

The exhibition illustrates Josephine's tastes and influence on French decorative arts showing some of her luxurious furnishings, tableware, elegant dresses and jewels. The exhibition includes many portraits including a large painting of her by Prud'hon on loan from the Louvre and another one by Gros from the Musée Masséna in Nice.

We enjoyed the exhibition, which as the article above notes, displayed many artefacts, furniture, fine porcelain, sculpture, etc. One of the most famous paintings about the Empress Josephine was not included in the exhibition because, I presume, its size precluded its display in the Luxembourg's gallery setting:

(Jacques-Louis David's The Coronation of Napoleon, from Wikipedia commons). The gift shop did feature postcards of this huge painting in the Louvre (32.1 foot by 20.4 ft). I bought the Dossier de L'Art magazine about the exhibition because it had many good photographs of artefacts we found interesting and beautiful. The lady in the coat check asked us if we had enjoyed the exhibition, and we said yes. My husband commented on how sad it was that Napoleon had divorced Josephine because she could not or had not borne him an heir. She commented in reply that "He was not a very nice man." Mark responded, "Well, at least he didn't cut off her head, like Henry VIII!" I have taught him well.

(Jacques-Louis David's The Coronation of Napoleon, from Wikipedia commons). The gift shop did feature postcards of this huge painting in the Louvre (32.1 foot by 20.4 ft). I bought the Dossier de L'Art magazine about the exhibition because it had many good photographs of artefacts we found interesting and beautiful. The lady in the coat check asked us if we had enjoyed the exhibition, and we said yes. My husband commented on how sad it was that Napoleon had divorced Josephine because she could not or had not borne him an heir. She commented in reply that "He was not a very nice man." Mark responded, "Well, at least he didn't cut off her head, like Henry VIII!" I have taught him well.

Published on March 20, 2014 22:30

March 13, 2014

On Today's Itinerary: The Crown of Thorns

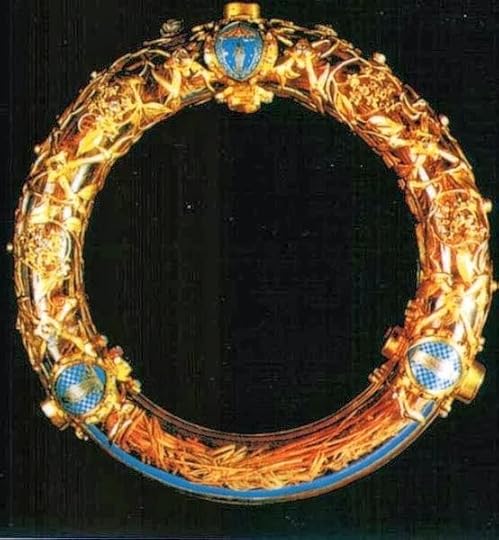

At 3:00 p.m. (15:00) today, I hope to be in Notre Dame Cathedral for the Veneration of the Crown of Thorns, held every Friday during Lent:

The relics of the Passion presented at Notre-Dame de Paris include a piece of the Cross, which had been kept in Rome and delivered by Saint Helen, the mother of Emperor Constantine, a nail of the Passion and the Holy Crown of Thorns.

Of these relics, the Crown of Thorns is without a doubt the most precious and the most revered. Despite numerous studies and historical and scientific research efforts, its authenticity cannot be certified. It has been the object of more than sixteen centuries of fervent Christian prayer.

Saint John tells that, in the night between Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, Roman soldiers mocked Christ and his Sovereignty by placing a thorny crown on his head (John 19:12).

The crown housed in the Paris cathedral is a circle of canes bundled together and held by gold threads. The thorns were attached to this braided circle, which measures 21 centimetres in diameter. The thorns were divided up over the centuries by the Byzantine emperors and the Kings of France. There are seventy, all of the same type, which have been confirmed as the original thorns.

That is, of course, assuming that flights from home to DFW to CDG and transportation to our apartment have all gone smoothly. This blog will definitely be more French than English for awhile.

A tout a l'heure!

Image credit: from Wikipedia commons under a Creative Commons license.

Published on March 13, 2014 22:30

March 11, 2014

"Bad Religion" and "Dangers to the Faith": Book Review, Part Two

I read Ross Douthat's Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics last month and then followed it up by reading Al Kresta's Dangers to the Faith: Recognizing Catholicism's 21st-Century Opponents. The two books are related, as both authors examine the Church's competition for what to believe, how to pray, how to live, and how to think. Douthat tells a story, tracing a history of change and secularization and focusing on a handful of heresies--teachings about Christianity that over-emphasize one doctrine or another and thus distort Christian orthodoxy (using a Mere Christianity view). Kresta writes about 14 opponents of the Catholic Church divided into four groups: Abusers of Spirituality and Revelation; Abusers of Science and Reason; Abusers of the Past and Future, and Abusers of Wealth and Power. Douthat's book is a narrative to be absorbed and analyzed, with a conclusion that emphasizes personal action; Kresta's is is a compendium of information to be consulted and used as a reference for refutation and argument. As I reviewed Bad Religion yesterday, today I focus on Dangers to the Faith.

To begin, I think I should note that Al Kresta has interviewed me a few times on his radio program; he and Nick Thomm even reached out to me to set up an interview on site at the Catholic Writers Guild Conference. Nevertheless, neither he nor OSV sent me a review copy or asked for my opinion. I bought my copies of both Bad Religion and Dangers to the Faith at Eighth Day Books. I have also listened to Al Kresta's program often and was more familiar with his way of reasoning and presenting his arguments than I was with Douthat's--in fact, although I've heard of Douthat and seen and heard interviews on broadcast media, this was the first work of his I'd read. Reading Dangers to the Faith is like listening to Al Kresta: his story-telling method; his way of presenting his side of the argument and deflating the other side's argument--they come through clearly here. His voice is unmistakable on the printed page.

As Kresta presents the 14 dangers to the Faith, he quotes extensively from the sources of the dangers' founders and exponents. Each chapter is dedicated to a specific danger, outlining its tenets and contradiction of Catholic Truth, and then describing arguments against it. The book does not have an index, but it does have pages of notes so you have the sources and resources for further reading. I saw Mr. Kresta on Raymond Arroyo's The World Over program and he commented that these 14 dangers are all abusers of goods. They take something good, like understanding nature through the scientific method, and twist it so that the scientific method becomes the only way to understand life. In that way, these abusers of goods resemble Christian heretics, who take some aspect of the truth, for example, Christian teaching on Who Jesus is and over emphasize it like the Arians or the Monophysites. In a way, both Kresta's "abusers of goods" and Douthat's "heretics" are narrow minded and limited: they cannot see the complexity of reality and so try to manage it by bringing reality down to their level. It may be difficult to understand the relationship between Faith and Reason or how Jesus could be True God and True Man, but it's better to try and fail than to adopt an unrealistic minimalization of the truth so you can handle either truth.

In addition to commenting on the voice so evident in these chapters, I'd like to mention the tone: Kresta is always charitable, sometimes a little exasperated, but never demeaning or disparaging. He speaks of these "enemies" with love, because he wishes they knew the truth. Using the example of Oprah Winfrey's encounter with the Dominican Sisters of Mary, Kresta demonstrates how much she knew something great and good was there--she just didn't recognize Who was there.

Kresta achieves his goals in helping his readers "know and love the faith" and "love the mission field" (from the Introduction). I did find the subheads, used not just for sections but for paragraphs, rather distracting, and I do wish the book had an index. Dangers to the Faith is an excellent resource and reference. Kresta ends his book just as Douthat did: with a call to sanctity for all Catholics as the best apologetic argument we can make.

Published on March 11, 2014 22:30

March 10, 2014

"Bad Religion" and "Dangers to the Faith": Book Reviews, Part One

I read Ross Douthat's Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics last month and then followed it up by reading Al Kresta's Dangers to the Faith: Recognizing Catholicism's 21st-Century Opponents. The two books are related, as both authors examine the Church's competition for what to believe, how to pray, how to live, and how to think. Douthat tells a story, tracing a history of change and secularization and focusing on a handful of heresies--teachings about Christianity that over-emphasize one doctrine or another and thus distort Christian orthodoxy (using a Mere Christianity view). Kresta writes about 14 opponents of the Catholic Church divided into four groups: Abusers of Spirituality and Revelation; Abusers of Science and Reason; Abusers of the Past and Future, and Abusers of Wealth and Power. Douthat's book is a narrative to be absorbed and analyzed, with a conclusion that emphasizes personal action; Kresta's is is a compendium of information to be consulted and used as a reference for refutation and argument.

In Bad Religion, Douthat starts (in Part I) from a time in the mid-twentieth century when the Catholic Church (in the person of Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen), the mainline Protestant churches (Reinhold Niebuhr); the evangelical/fundamentalist churches (Billy Graham), and the African-American Christian churches (Martin Luther King, Jr) each presented an effective, persuasive, and cohesive vision of Christian orthodoxy. Within the limits of their Reformation driven divisions, they were agreed upon the influence Christianity should have on culture. Douthat highlights the Civil Rights movement as the case study of that unity and effectiveness.

But then it all fell apart: secularization and accommodation to the cultural and moral shifts of the 1960's and 1970's weakened the prophetic voice of Christianity in America. Douthat particularly examines the decline of the Catholic Church in the wake of the Second Vatican Council--the decline in vocations, Mass attendance, orthodoxy and orthopraxy--although he also analyzes the revival of Catholicism during the pontificate of Blessed John Paul II, and the many Catholic organizations, colleges, and publications that drove that revival. I have often heard comments that when the history of the Catholic Church in twentieth century America is written someday, Mother Angelica's EWTN will be commended for its influence--but Douthat does not mention it in this book. He analyzes the alliance between Catholics and Evangelicals at the same time noting the separation between Catholics and mainline Protestant churches, both centering around social issues like abortion, the definition of marriage, and the place of religion in public discourse.

In Part II he examines four heresies (and here he and Kresta overlap in both the heresies/dangers they highlight): the campaign to displace the New Testament with the Gnostic gospels and an alternative view of orthodox doctrine about the Incarnation of Jesus; the popularity of the Prosperity gospel; New Age spirituality; and over identification of Christianity with the American nation and republic (Christian Nationalism). All four present versions of Christian teaching that are more attractive than Christian orthodoxy because they reduce the moral and spiritual demands of religion for anyone who wants to follow Jesus. For example: instead of "pick up your cross", bear sufferings in unity with Christ, and observe poverty of spirit and material possessions, the Prosperity gospel says enjoy life now, see your wealth and comfort as signs of God's favor, expect great things now. Just like the Gnostic gospels, the Prosperity gospel cannot face the real example of suffering and redemption held out by the true Good News. But they seem easier and less demanding, just like the other two heresies--until you realize that they do nothing to help you face the real sorrows and joys of human life (that's my interpretation, not necessarily Douthat's). If, like Elizabeth Gilbert, you base your current and eternal happiness on the realization of "the God Within", you have a pretty weak foundation: fallible, mortal, self-serving and ultimately ineffective. (Kresta is particularly effective with his analysis of New Age spirituality.)

Finally, I appreciate Douthat's concluding remarks about what Christians need to do if they want to see Orthodoxy thrive again, because he focuses on what you and I can do. He cites G.K. Chesterton's comment from The Everlasting Man that the Church should have died at least five times before in its two thousand (2,000) year history--but didn't. His suggestions focus on knowing what Christians believe, knowing the reasons for our hope so we can express it, and living according to those beliefs and reasons are better than any master plan--well, I guess they are the Master's plan! He also encourages Christians to avoid syncretism as they work together on certain issues, to be true to their own community's beliefs, and he quotes Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, before he became pope: "The only really effective apologia for Christianity comes down to two arguments, namely, the saints the Church has produced and the art which has grown in her womb." (from The Ratzinger Report). Therefore, Douthat says, be saints and artists!

Table of Contents

Prologue: A Nation of Heretics

Part I Christianity in Crisis

1 The Lost World

2 The Locust Years

3 Accommodation

4 Resistance

Part II The Age of Heresy

5 Lost in the Gospels

6 Pray and Grow Rich

7 The God Within

8 The City on the Hill

Conclusion: The Recovery of Christianity

Notes

Acknowledgments

Index

More on Dangers to the Faith: Recognizing Catholicism's 21st-Century Opponents tomorrow.

Published on March 10, 2014 22:30

St. John Ogilvie, SJ

According to this CNA story, Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI encouraged devotion to St. John Ogilvie in February of 2010, before his visit to Scotland and England in September that year--then mentioned him again at the Mass at Bellahouston Park in Glasgow the day of his arrival:

According to this CNA story, Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI encouraged devotion to St. John Ogilvie in February of 2010, before his visit to Scotland and England in September that year--then mentioned him again at the Mass at Bellahouston Park in Glasgow the day of his arrival:March 10 is the liturgical memorial of Saint John Ogilvie, a 16th-and 17th-century Scotsman who converted from Presbyterianism to Catholicism, served as a Jesuit priest, and died as a martyr at the hands of state officials. St. John was executed for treason, refusing to accept King James I’s claim of supremacy over the Church. Pope Paul VI canonized him in 1976, making him Scotland’s first canonized saint for several hundred years [since 1250!]

In February 2010, during a visit to Rome by the Scottish bishops’conference, Benedict XVI asked the bishops to promote devotion to St. John Ogilvie among priests – since the Jesuit martyr had been “truly outstanding in his dedication to a difficult and dangerous pastoral ministry, to the point of laying down his life.” Later that year, during the Scottish segment of his U.K. visit, the Pope again encouraged priests to look to the saint’s “dedicated, selfless and brave” example.

The Jesuit Vocations website in Great Britain describes his early life and conversion:

John Ogilvie was born in 1579 and brought up in the Calvinist tradition. He was six or seven years old when Mary Queen of Scots died on the scaffold. He grew up as a child in a Scotland which had rejected her, and with her the old faith of his fathers. At the age of twelve he crossed to the continent in pursuit of education. But travelling in Europe broadened his mind, and he decided to become a Catholic, ending up at a Jesuit college in Austria. A year later, in 1599, he entered the Jesuit novitiate, and followed the normal Jesuit programme of noviceship, philosophy, and school teaching, in Vienna, before he was ordained in Paris in 1610.

After his capture in Glasgow, he endured great tortures:

The archbishop hit John Ogilvie in the face and said, "you are over bold to say your Masses in a reformed city," to which the Jesuit, replied, "You act like a hangman, not a bishop, in striking me." He was then beaten up by the archbishop's men, and taken off to prison and interrogation, but he never lost his spirit.

The cell they put him in stank, his feet where weighed down, and he was tortured before being taken to Edinburgh to appear before a council appointed by King James I of England (James VI of Scotland). There he was tortured by sleep deprivation for nearly ten days until December 22, but still refused to divulge names of those he had worked with or lived with. So he was sent back to prison in Glasgow, where he managed to write an account of what had happened to him since his arrest, and have it smuggled out and sent to his Jesuit superior.

His final interrogation was in January, when King James who considered himself a theologian and had taken an interest in the case, had devised some questions for him, the answer to which must be either the denial of the pope's supremacy and the assertion of the king's in religious matters, or must condemn him for treason. John Ogilvie replied that only the pope, and not the king, had power in religious matters, and also that the pope could both excommunicate and depose the king. When the king read these responses he gave orders that John was to be tried on March 10 and executed if he would not change.

At 11 a.m. at Tollbooth in Glasgow John went on trial for high treason. He was found guilty by lunchtime, and executed at 4 p.m. He kissed the scaffold as he went, and spent some time in prayer, then was pushed off the ladder Since he did not die immediately, the hangman pulled on legs to finish the agony. Unusually, and despite the sentence he had been given, his body was not quartered but buried in a criminal’s graveyard.

The CNA story offers these further details of his execution:

Attempts to ply John with bribery – in exchange for his return to Protestantism, and his betrayal of fellow Catholics – continued even as he was being led to his execution. His own defiant words are recorded: for the Catholic faith, he said, he would "willingly and joyfully pour forth even a hundred lives. Snatch away that one which I have from me, and make no delay about it, but my religion you will never snatch away from me!"

Asked whether he was afraid to die, the priest replied: “I fear death as much as you do your dinner.” St. John Ogilvie was executed by hanging on March 10, 1615.

As a last gesture before his hanging, St. John had tossed his Rosary beads into the crowd where they were caught by a Calvinist nobleman. The man, Baron John ab Eckersdorff, later became a Catholic, tracing his conversion to the incident and the martyr’s beads.

A prayer for the courage to imitate St. John Ogilvie:

God our Father, fountain of all blessing, We thank you for the countless graces that come to us in answer to the prayers of your saints. With great confidence we ask you in the name of your Son and through the prayers of St John Ogilvie to help us in all our needs.

Lord Jesus, you chose your servant St John Ogilvie to be your faithful witness to the spiritual authority of the chief shepherd of your flock. Keep your people always one in mind and heart, In communion with [Francis] our Pope, and all the bishops of your Church.

Holy Spirit, you gave St John Ogilvie light to know your truth, wisdom to defend it, and courage to die for it. Through his prayers and example bring our country into the unity and peace of Christ’s kingdom. Amen.

Published on March 10, 2014 00:08

March 9, 2014

Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk Born

The surname Howard comes up often on this blog, and just like any other post on the Howard family, our challenge today is to keep all the people named Thomas, Henry, Elizabeth, Anne, Margaret, and Mary straight, not to mention the Earls, Dukes, and Lords so that the whole story makes sense and we can understand the impact of all these relationships and plots!

The surname Howard comes up often on this blog, and just like any other post on the Howard family, our challenge today is to keep all the people named Thomas, Henry, Elizabeth, Anne, Margaret, and Mary straight, not to mention the Earls, Dukes, and Lords so that the whole story makes sense and we can understand the impact of all these relationships and plots!Here goes:

Today's Howard was born on March 10, 1536. He was the grandson of Thomas Howard, the 3rd Duke of Norfolk, who was uncle to two of Henry VIII's consorts, Anne Boleyn (Elizabeth Howard married Thomas Boleyn) and Catherine Howard (Edmund Howard's daughter).

The 4th Duke of Norfolk's father was Henry Howard, the Earl of Surrey, who was executed just days before Henry VIII died. Thomas Howard the 4th thus succeeded to the family title when his grandfather died in 1554. His mother, by the way, was Frances de Vere of Oxford.

John Foxe, the great Protestant martyrologist and hagiographer, was a teacher of today's Thomas Howard. Howard and his brother Henry Howard, lst Earl of Northampton were under the care of their evangelical aunt, Mary Howard FitzRoy, Duchess of Richmond and Somerset, widow of Henry FitzRoy, Henry VIII's only recognized illegitimate son. Howard continued to patronize Foxe, but Howard also began to involve himself in political efforts to promote Catholicism in England. (His brother Henry would be known as a crypto-Catholic and fall out of Elizabeth's favor.) Note that when Thomas Howard the 3rd was released from the Tower of London at the beginning of Mary I's reign he told John Foxe to find new employment.

Thomas Howard the 4th married thrice and the fourth marriage he attempted got him into big trouble, to say the least. His first wife was Mary FitzAlan, heiress to the Arundell estates. Their son was Philip Howard, 20th Earl of Arundell and Catholic martyr/saint. (Mary died after his birth in 1557.)

His second wife was a widow-heiress, Margaret Audley (Lady Jane Grey's first cousin). Their eldest son, another Thomas Howard, later 1st Earl of Suffolk, was one of Queen Elizabeth's admirals in the battle against the Spanish Armada and survived to serve James I for many years. The younger son was William Howard, who would be imprisoned as a Catholic by Elizabeth I like his half-brother Philip.

His third wife was another widow, Elizabeth Leyburne Dacre, whose first husband was Thomas Dacre, 4th Baron Dacre. Elizabeth Leyburne's family were recusant Catholics. By her first marriage she had three daughters and Thomas Howard the 4th arranged marriages between her three daughters and his three sons after her death in 1567:

Anne Dacre married Philip Howard (their son was named Thomas)

Elizabeth Dacre married William Howard

Mary Dacre married Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk (and died soon after)

Thomas Howard the 4th's sister Jane was married to Charles Neville, 6th Earl of Westmoreland, a Catholic peer in the North of England. Neville joined Thomas Percy, the 7th Earl of Northumberland in the Northern Rebellion against Elizabeth I in 1569.

Jane Howard Neville encouraged her brother to marry the former Queen of Scotland who was now Elizabeth's prisoner or guest, having sought refuge in 1568, hoping for assistance in regaining her throne. But Elizabeth first wanted to find out if Mary was at all implicated in the murder of Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. So by November of 1569, Mary's position was precarious--and this idea of the Earl Marshall of England marrying the Catholic threat to Elizabeth's throne, while the North of England was rebelling, led to Thomas Howard the 4th's imprisonment in the Tower of London.

At the same time, of course, Mary, the ertswhile Queen of Scot was still Elizabeth's most likely successor, since she had rejected the claims of the Grey family. Since Elizabeth was not married, and did not seem likely to be married, any discussion of or action that might influence the succession was very dangerous, as the surviving Grey sisters, Catherine and Mary, found out when they married without Elizabeth's approval.

In the meantime, of course, the Northern Rebellion had fallen apart; Percy and Neville had fled to Scotland and Elizabeth's retribution on the rebels was proceeding apace. Evidently, imprisonment in the Tower somehow led Thomas Howard the 4th to greater designs against Queen Elizabeth. Upon his release he became involved in the Ridolfi Plot of 1570 which aimed at executing the Queen and placing Mary, Queen of Scots (and her consort, Thomas I, King of England?) on the throne. The plot was discovered by Elizabeth's spy network and Thomas Howard the 4th was executed for treason on June 2, 1572. His lands and titles were forfeit to the throne, of course.

His son Philip Howard, however, would succeed to his maternal grandfather's title, the Earl of Arundel, when Henry FitzAlan died in 1580--but he ended up dying in the Tower of London, perhaps just because Elizabeth feared a Howard in exile, supported by the Pope and Catholic monarchs. Nevertheless, Elizabeth restored Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk to the blood in 1584 and he served her in various offices and efforts, including the trial of Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex, but ended up leaving office under James I in some disgrace. Thomas Howard the 4th's youngest son, William Howard became a Catholic in 1584, lived in retirement and recusancy in Naworth Castle, Cumberland and died in 1640.

Published on March 09, 2014 22:30

March 8, 2014

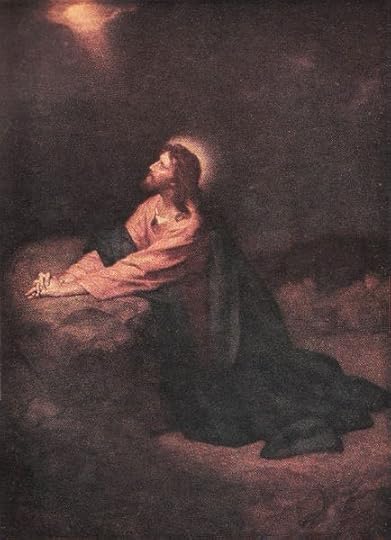

St. Thomas More's "The Sadness of Christ"

According to Seymour Baker House in the 29th volume of

Renaissance and Reformation

(2005), St. Thomas More wrote De Tristitia Christi/The Sadness of Christ as "A Martyr's Theology of Assent". You may access the .pdf of the article from that link. As House unfolds his thesis, he notes that More's exegesis of Jesus's Agony in the Garden serves as a preparation for martyrdom, if not for himself, for those who follow after him.

According to Seymour Baker House in the 29th volume of

Renaissance and Reformation

(2005), St. Thomas More wrote De Tristitia Christi/The Sadness of Christ as "A Martyr's Theology of Assent". You may access the .pdf of the article from that link. As House unfolds his thesis, he notes that More's exegesis of Jesus's Agony in the Garden serves as a preparation for martyrdom, if not for himself, for those who follow after him. As I am reading The Sadness of Christ this Lent, I have been meditating on the long passage in which More considers distractions during prayer. He calls out their danger and he reflects on how incredibly inappropriate they are to the situation. More describes how we can dress up for Holy Mass--thinking we are honoring God through our attire--and then contradict that thought by cleaning our finger nails, picking our noses, thinking about many other things, and forgetting where we are entirely in the course of the Mass. He contrasts those distractions to the serious position we are in as suppliants to Almighty God, to whom we owe everything and on whom we depend for everything.

In one crucial passage, he asks the reader to imagine what would happen if a subject went before a mere human king and asked for pardon. Suppose the subject was accused--and was guilty of--treason and faced mortal death. Would he go before the monarch and while pleading for mercy, act distracted and unconcerned? Would he "yawn, stretch, sneeze, spit without giving it a thought, and belch up the fumes of [his] gluttony"? Of course not: he would be attentive, respect the office and person of the monarch, and pray for his mercy!

More then goes on to show that Jesus gave us a pattern of prayer to follow, culminating in the Agony of the Garden: praying intensely, body and soul, reverent and devoted to God His Father.

In Seymour Baker House's article on De Tristitia Christi (More wrote this Tower Work in Latin), he comments on the controversy over interpretation of Christ's Agony in the Garden vis-a-vis the mystery of His Person: True God and True Man, the Divine Second Person of the Trinity incarnate, with a human nature, human will (and Divine nature and Divine will). Did Jesus really fear the suffering and torture He faced and death on the cross?

I remember writing about how John Colet and Desderius Erasmus debated that mystery when I studied Erasmus as an undergraduate. Colet took the line of St. Jerome and other Fathers that this sorrow was not for His own death, but for the coming destruction of Jerusalem. Erasmus agreed with St. Cyril of Alexandria that this sorrow and fear was appropriate for Jesus to express, just as He endured the temptations of Satan in the dessert after praying and fasting for 40 days. He endured temptation without giving in, of course, just as He endured fear and sorrow and remained obedient to His Father's will.

More on St. Thomas More's De Tristitia Christi next Sunday.

Illustration: Christ in Gethsemane by Heinrich Hofmann.

Published on March 08, 2014 22:30

March 6, 2014

Virtually Restoring St. Augustine's Abbey

The Kent School of Architecture will virtually rebuild St. Augustine of Canterbury's Abbey:

Architectural Visualisation students were treated to an insight into the past when English Heritage visited the school to talk about the nearby St. Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury. The archaeological site is the subject of the students’ latest project, Virtual Cities, which redirects techniques and skills typically used to visualise prospective architectural proposals, to reanimate the past.

The project will see students rebuild the Abbey to its former glory prior to the suppression by King Henry VIII in the 1530s. The virtual model is designed to be fully navigable, allowing audiences the chance to experience the abbey complete with interpretations of the interior spaces and decoration.

Howard Griffin, Programme Director of the MA Architectural Visualisation courses said, “This is an exciting collaboration between the School of Architecture and English Heritage. Our students have the chance to work with archaeological experts in recreating the past. Much of the learning students are engaged with on this course is aimed at visualising the future. However, we can use these same processes and skills to recreate the past as well. Using real-time games technology allows audiences to navigate their way through a space in a way which cannot be achieved with simple computer animation.”

The project presents new challenges to the students, who ordinarily can rely on accurate architect’s drawings as a source of information. Most of the Abbey and outer buildings were destroyed and little evidence remains of large parts of the site. Collections Curator at English Heritage, Rowena Willard-Wright explained, “This project will be like building a jigsaw puzzle, but with only 3 pieces remaining.”

The first stage of the St. Augustine Abbey project is due to be completed by spring, with additional work and detailing to be completed later.

The ruins of St. Augustine's Abbey are a UNESCO World Heritage Site under the care and maintenance of the English Heritage organization. The last abbot was John Essex and he and his monks surrendered the abbey to Henry VIII's commissioners on July 30, 1538, ending almost one thousand years of monasticism on that site (940 years). Henry VIII took over the site to build himself a palace. More on the history of the monastery here.

Image credit: Wikipedia commons.

Published on March 06, 2014 22:30