Stephanie A. Mann's Blog, page 242

April 1, 2014

Jacques le Goff, RIP

According to

The Guardian

, historian Jacques le Goff has died:

According to

The Guardian

, historian Jacques le Goff has died:The historian Jacques Le Goff died in Paris on Tuesday aged 90, his family told newspaper Le Monde.

Over a long and influential career in academia and public broadcasting, Le Goff transformed views of the middle ages from a dark and backward time to a period that laid the foundations for modern western civilisation.

He was a leading proponent of "new history" – the shift in historical research from emphasis on political figures and events to mentality and anthropology. . . .

His many books included works on middle age intellectuals, bankers and merchants, a biography of King Louis IX and a seminal work on the introduction of the concept of purgatory.

"By transforming our view of the middle ages, you have changed the way we deal with history," Le Goff was told when awarded the prestigious Dr AH Heineken prize for history in 2004, whose jury described him as "without doubt the most influential French historian alive today".

I think that Le Goff's views of the middle ages were certainly shared by and articulated very effectively by Christopher Dawson in England and the USA, through his research on the spiritual tradition (Christianity) that infused Western Civilization. And Regine Pernoud's Those Terrible Middle Ages! also helped strip away the darkness imposed on the Middle Ages by the Enlightenment. But in popular thought (if that's not a contradiction in terms) the Middle Ages is still the dark, benighted, superstitious (that is, Catholic) era between the brightness of Greece and Rome and the rebirth of that brightness in the Renaissance (witness the EU's proposed constitution, which skips the era entirely!). Perhaps the fact that Le Goff was an agnostic helped his argument for the Middle Ages prevail in academia!

One of Le Goff's most influential books was The Birth of Purgatory, translated by Arthur Goldhammer for The University of Chicago Press:

In The Birth of Purgatory, Jacques Le Goff, the brilliant medievalist and renowned Annales historian, is concerned not with theological discussion but with the growth of an idea, with the relation between belief and society, with mental structures, and with the historical role of the imagination. Le Goff argues that the doctrine of Purgatory did not appear in the Latin theology of the West before the late twelfth century, that the word purgatorium did not exist until then. He shows that the growth of a belief in an intermediate place between Heaven and Hell was closely bound up with profound changes in the social and intellectual reality of the Middle Ages. Throughout, Le Goff makes use of a wealth of archival material, much of which he has translated for the first time, inviting readers to examine evidence from the writings of great, obscure, or anonymous theologians.

His most recently published book is about The Golden Legend, published by Princeton University Press: In Search of Sacred Time: Jacobus de Voragine and The Golden Legend:

It is impossible to understand the late Middle Ages without grasping the importance of The Golden Legend, the most popular medieval collection of saints' lives. Assembled for clerical use in the thirteenth century by Genoese archbishop Jacobus de Voragine, the book became the medieval equivalent of a best seller. By 1500, there were more copies of it in circulation than there were of the Bible itself. Priests drew on The Golden Legend for their sermons, the faithful used it for devotion and piety, and artists and writers mined it endlessly in their works. In Search of Sacred Time is the first comprehensive history and interpretation of this crucial book. Jacques Le Goff, one of the world's most renowned medievalists, provides a lucid, compelling, and unparalleled account of why and how The Golden Legend exerted such a profound influence on medieval life.

In Search of Sacred Time explains how The Golden Legend--an encyclopedic work that followed the course of the liturgical calendar and recounted the life of the saint for each feast day--worked its way into the fabric of medieval life. Le Goff describes how this ambitious book was carefully crafted to give sense and shape to the Christian year, underscoring its meaning and drama through the stories of saints, miracles, and martyrdoms. Ultimately, Le Goff argues, The Golden Legend influenced how medieval Christians perceived the passage of time, Christianizing time itself and reconciling human and divine temporality.

Authoritative, eloquent, and original, In Search of Sacred Time is a major reinterpretation of a book that is central to comprehending the medieval imagination.

Published on April 01, 2014 22:30

March 31, 2014

The Queen and I, Part II: Book Review

Beth von Staats reviews my book on her blog:

Supremacy and Survival, How Catholics Endured the English Reformation is a triumph of comprehensive brevity. In a mere 149 pages, Stephanie A. Mann tackles head-on and convincingly from a Roman Catholic point of view the Henrican and Protestant Reformations of England and later Great Britain, beginning the with way of life of Roman Catholics living prior to Henry VIII’s decision to annul his marriage to Catalina de Aragon straight through to the British Roman Catholic Emancipation of the 19th century and beyond. Just how does Mann pull off this seemingly impossible feat? Stephanie A. Mann is a educator, and like any great teacher, she sticks to the facts, points to the obvious and allows her reader to absorb what for many will be a true enlightenment. Our English historical heroes were not as religiously tolerant as we thought. Our English historical villains were not so condemnable as we were led to believe. They never taught us any of this in history class or Sunday School. Who knew?

What's different about this review is that Beth comes from a historical fiction community that has Anne Boleyn as its heroine. If you are interested in Tudor dynastic history, you know that Anne Boleyn is a crucial figure. She can also be a controversial figure: either the heroine of the era or the terrible villainess of English history--as Hilary Mantel (and others have said something similar) wrote in The Guardian in 2012, "Anne Boleyn is one of the most controversial women in English history; we argue over her, we pity and admire and revile her, we reinvent her in every generation. She takes on the colour of our fantasies and is shaped by our preoccupations: witch, bitch, feminist, sexual temptress, cold opportunist." In summary: Anne Boleyn fascinates many for many reasons--and of them has been her reputation as a reformer, with evangelical (Lutheran) sympathies.

One might expect that my book, with its focus on what Catholics suffered during and after the English Reformation, could be seen as an attack on Anne Boleyn or even an attack on English Protestantism as it developed. But I think throughout Supremacy and Survival, I practiced charity toward all the historical personages, not ever attacking their persons--sometimes weighing their actions in a balance of justice and pointing out general inconsistencies--but never naming anyone a villain or villainess. My thesis about the English Reformation has been tested, based as it is on the work of great scholars like Eamon Duffy, Christopher Haigh, et al--and when I read Alister McGrath's Christianity's Dangerous Idea: The Protestant Revolution (San Francisco: Harper One, 2007), I was more assured I had it right. That's why I appreciate this review so much: it is not only fair to my thesis, but argues for readers to be open to my argument--and to some of its implications.

As Beth concludes in her review:

If you are looking for an apologetic view of English and Welsh history, you will not find it in Supremacy and Survival, How Catholics Endured the English Reformation . If you are Anglican or even if another Protestant denomination, you may find some of what Stephanie A. Mann teaches unsettling. Read the book anyway. Learn English history through the eyes of of the Roman Catholic experience. You will hear the voices of English and Welsh Roman Catholics, hundreds martyred for their faith alone, clear and strong — and for many of you, perhaps for the first time. Hear them roar.

Published on March 31, 2014 22:30

March 30, 2014

What Did Thomas More Mean in "Utopia"?

Stephen Smith looks at Thomas More's Utopia in The Wall Street Journal, in its weekly Masterpiece column:

For some, "Utopia" provides a witty education in human nature for citizens and leaders, especially those who want to be "well and wisely trained." For others, "Utopia" heralds the glorious liberty of communism to come, or so the makers of Moscow's Memorial Obelisk thought when they engraved More's name there in 1918. In More's own words, Utopia is "a truly golden book, no less profitable than delightful," but what kind of education does this book really offer? While the word "Utopia" has long been shorthand for any ideal world, a careful reading of More's book offers a complex, and better, view.

Born in London in 1478, More distinguished himself in family life and friendship, in professional work and politics. Called by Erasmus "the only true genius in England," More published "Utopia" in Latin in 1516. He then entered King Henry VIII's service, and eventually became Lord Chancellor. During his maturity, the drama of Henry's divorce and the Reformation engulfed England. A supporter of neither, and a defender of English law, ancient liberty and the Catholic faith, More resigned his public office in 1532 after a controversial tenure. Later imprisoned, he was convicted of treason and sentenced to death in 1535. His last words—"I die the king's good servant, and God's first"—attest that he had served his old friend Henry with integrity throughout the storms.

Smith, a professor in English Literature at Hillsdale College, provides a summary of the conversation at the heart of Utopia and then concludes:

Surprisingly, "Utopia" concludes not with a cross-examination of Raphael, but with More thinking to himself that Utopia sounds "really absurd," a point often missed by those who wish to embrace its radical policies. Unsure that Raphael can "take contradiction in these matters," More decides to lead him to dinner instead. For Raphael, Utopia is over, and he may have placed himself beyond the reach of friendship, though More's charity creates hope. For readers, we are left with the challenge of responding to Raphael's claims and examining the sources of our own thoughts and first principles—and indeed, the clarity of our own self-knowledge. For Thomas More, his truly golden meditation on service and Utopia would meet its end only years later, alone atop a scaffold on Tower Hill.

Read the rest here. That last paragraph reminded me of Pope Benedict XVI's address to Politicians, Diplomats, Academics and Business Leaders in Westminster Hall, City of Westminster, on Friday, September 17, 2010:

In particular, I recall the figure of Saint Thomas More, the great English scholar and statesman, who is admired by believers and non-believers alike for the integrity with which he followed his conscience, even at the cost of displeasing the sovereign whose “good servant” he was, because he chose to serve God first. The dilemma which faced More in those difficult times, the perennial question of the relationship between what is owed to Caesar and what is owed to God, allows me the opportunity to reflect with you briefly on the proper place of religious belief within the political process. . . .

And yet the fundamental questions at stake in Thomas More’s trial continue to present themselves in ever-changing terms as new social conditions emerge. Each generation, as it seeks to advance the common good, must ask anew: what are the requirements that governments may reasonably impose upon citizens, and how far do they extend? By appeal to what authority can moral dilemmas be resolved? These questions take us directly to the ethical foundations of civil discourse. If the moral principles underpinning the democratic process are themselves determined by nothing more solid than social consensus, then the fragility of the process becomes all too evident - herein lies the real challenge for democracy.

Published on March 30, 2014 22:30

March 29, 2014

Marie de Medici, Arthur Rimbaud, and Les Filles du Calvaire

On our way from the Hotel de Ville to the Luxembourg Gardens a couple of weeks ago, we passed by some familiar sights and also saw some things for the first time. We walked across the parvis of the Hotel de Ville from the metro, and then across the bridges over the Seine to the Ile de la Cite and to the Left Bank, stopping at Le Depart de St. Michel as we always do, this time for a couple of cafe cremes. After enjoying some people watching on that busy corner, we started down Blvd. St. Michel.

On our way from the Hotel de Ville to the Luxembourg Gardens a couple of weeks ago, we passed by some familiar sights and also saw some things for the first time. We walked across the parvis of the Hotel de Ville from the metro, and then across the bridges over the Seine to the Ile de la Cite and to the Left Bank, stopping at Le Depart de St. Michel as we always do, this time for a couple of cafe cremes. After enjoying some people watching on that busy corner, we started down Blvd. St. Michel.We took a little jaunt off St. Michel to the Place St. Andre des Arts and then headed down Rue Danton to Blvd. St. Germain, pausing to notice the statue of Danton proclaiming "Il nous faut de l'audace, encore de l'audace, toujours de l'audace!

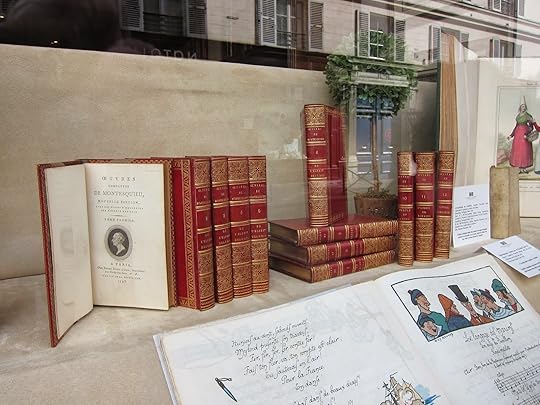

A left turn on Rue de Seine/Rue de Tournon gave us an opportunity for some window shopping: shoes and books:

A left turn on Rue de Seine/Rue de Tournon gave us an opportunity for some window shopping: shoes and books:

Finally reaching Rue de Vaugirard, we ducked into the Jardins du Luxembourg on our way to lunch at a cafe we've been to before, and visited the Medici fountains, with bronze Polyphemous discovering Acis and Galatea:

After lunch, we returned to Rue Vaugirard. Walking toward the Musee du Luxembourg, we saw the entrance to the Convent of the Filles du Calvaire, the congregation founded by by Antoinette of Orléans-Longueville in 1617 in Poitiers. This convent was built in 1625, and Marie de Medici's initials and face are featured prominately on the door and above the entrance:

Les Filles du Calvaire, according to the

Catholic Encyclopedia

, were founded for more strict observance of the Benedictine Rule after Antoinette had worked to reform the famous Abbey of Fontevrault. This famous double monastery was the site of the graves of Henry II, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Richard I and other English royalty--but their bodies were desecrated during the French Revolution when the monasteries--like the convent at the Palais du Luxembourg--were suppressed in 1792. After we toured the Josephine exhibit at the Musee du Luxembourg--and that was a very appropriate venue for the exhibit because she was held in the Palais du Luxembourg while it served as a prison during the French Revolution--we decided to ride a taxi back to Hotel de Ville for an easier trip back to the apartment. On the way to the taxi stand in front of St. Sulpice, we saw this poem of Arthur Rimbaud, "The Drunken Boat"/"Le Bateau Ivre" drawn on the wall along Rue Ferou:

Les Filles du Calvaire, according to the

Catholic Encyclopedia

, were founded for more strict observance of the Benedictine Rule after Antoinette had worked to reform the famous Abbey of Fontevrault. This famous double monastery was the site of the graves of Henry II, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Richard I and other English royalty--but their bodies were desecrated during the French Revolution when the monasteries--like the convent at the Palais du Luxembourg--were suppressed in 1792. After we toured the Josephine exhibit at the Musee du Luxembourg--and that was a very appropriate venue for the exhibit because she was held in the Palais du Luxembourg while it served as a prison during the French Revolution--we decided to ride a taxi back to Hotel de Ville for an easier trip back to the apartment. On the way to the taxi stand in front of St. Sulpice, we saw this poem of Arthur Rimbaud, "The Drunken Boat"/"Le Bateau Ivre" drawn on the wall along Rue Ferou:

I who trembled, to feel at fifty leagues' distance

The groans of Behemoth's rutting, and of the dense Maelstroms

Eternal spinner of blue immobilities

I long for Europe with it's aged old parapets!

I have seen archipelagos of stars! and islands

Whose delirious skies are open to sailor:

- Do you sleep, are you exiled in those bottomless nights,

Million golden birds, O Life Force of the future? -

But, truly, I have wept too much! The Dawns are heartbreaking.

Every moon is atrocious and every sun bitter:

Sharp love has swollen me up with heady langours.

O let my keel split! O let me sink to the bottom!

If there is one water in Europe I want, it is the

Black cold pool where into the scented twilight

A child squatting full of sadness, launches

A boat as fragile as a butterfly in May.

I can no more, bathed in your langours, O waves,

Sail in the wake of the carriers of cottons,

Nor undergo the pride of the flags and pennants,

Nor pull past the horrible eyes of the hulks.

It is amazing how much beauty and history we find on any walk in Paris: I guess that's why we keep going back! All photos (C) Mark U. Mann, 2014.

Published on March 29, 2014 22:30

March 28, 2014

English Colonies in the New World

From the archives of

History Today

, how the Tudors (and the Stuarts) passed up the opportunity to colonize the New World:

From the archives of

History Today

, how the Tudors (and the Stuarts) passed up the opportunity to colonize the New World:But the English crown was not itself prepared to invest either men, material or money in such overseas enterprises. Henry VIII’s ambitions began and ended in France; the youthful Edward reigned for too short a time; Mary could not act so as to upset her Spanish husband; Elizabeth disguised parsimony as prudence; while James I signed a peace treaty with the nation’s colonial rival. Given such state disinterest, America remained peripheral to English policy while paramount for the Spanish purse.

Given a free hand, neither did English adventurers ever match the horizon-stretching deeds awarded to them on paper. Cabot, granted a continent, ventured inland “the shooting distance of a crossbow” before retreating to his ship. So, 150 years later, no Englishman had settled beyond the reach of the tide and all looked to the waterways for their succour: none had broken out from their beachhead to make the land their own.

In contrast to Spain, England did not find the New World a source of wealth and gold--except when English pirates seized gold from Spanish ships. Also, the English colonists did not export religion--rather they sought freedom from England's state church:

Given a religious homogeneity at home, Spain also exported Jesuits to proclaim and convert natives, often brutally, to the one true faith. By contrast, although every English Royal Charter included a paragraph on the need to spread the gospel, few English missionaries sailed to North America.

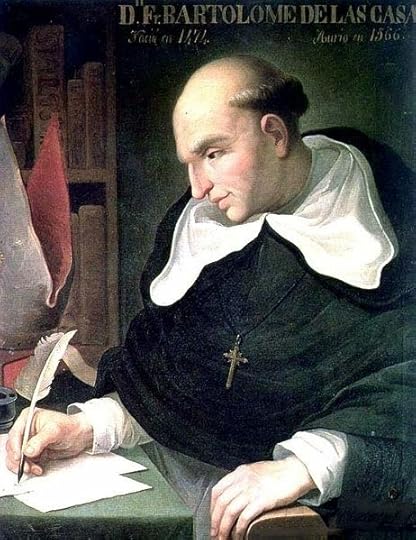

[That little dig, "often brutally" is an automatic anti-Jesuit response--since the topic is North America, I think the author should have included consideration of French Jesuit missionaries. Even Francis Parkman admitted that the French missionaries respected and treated the native Americans well. I don't think Blessed Junipero Serra is known for brutality toward the natives, nor Father Kino--and the author certainly forgets that Spain sent Dominican and Franciscan friars too! It certainly means the author ignored the great Bartolomé de las Casas, O.P., "Protector of the Indians", who protested against Spanish colonists' abuse of the natives. Those words "often brutally" just betray sloppy anti-Catholicism, in my opinion.]

[That little dig, "often brutally" is an automatic anti-Jesuit response--since the topic is North America, I think the author should have included consideration of French Jesuit missionaries. Even Francis Parkman admitted that the French missionaries respected and treated the native Americans well. I don't think Blessed Junipero Serra is known for brutality toward the natives, nor Father Kino--and the author certainly forgets that Spain sent Dominican and Franciscan friars too! It certainly means the author ignored the great Bartolomé de las Casas, O.P., "Protector of the Indians", who protested against Spanish colonists' abuse of the natives. Those words "often brutally" just betray sloppy anti-Catholicism, in my opinion.]

Indeed, the New World was seen as a place to despatch (sic) those, either Catholic or dissenting who, irritatingly, held to a doctrine deemed false. The export of such nonconformists began with the voyage of Mayflower in 1620 and reached a climax during the reign of Charles I, when thousands crossed the Atlantic to Massachusetts to escape from the persecution being instigated by Archbishop Laud. A similar exodus was to take Catholics to Maryland and Quakers to Pennsylvania.[Please see my article on Maryland here--I would say that the Catholics were not so much "despatched" as allowed to emigrate because of George Calvert, Lord Baltimore's past loyalty to James I.]

These people could not consider themselves to be sojourners; they had no future other than in the New World. However difficult life became, they had to make it work to survive because there was no going back. Their loyalties were to their community and they made their own laws to ensure that they could live and survive together. From rules, such as the Mayflower Compact, democracy in America was born. Thus, ironically, the future of the English New World was assured by those who arrived carrying the curse rather than the blessing of the court.

Although the phrase ‘British empire’, coined in 1577 by John Dee, gives the impression that Britannia wished to set her bounds ever wider for the glory of crown, country and the Protestant creed, the actuality is very different. The early argument for overseas settlement was, in truth, based around finding a passage to Cathay; discomforting Spain; settling indigent or criminal elements; monopolising the distant fishing grounds; searching for precious metals and resettling loyal but non-Anglican groups.

While all of these aims could claim to be in the national interest, the crown, apart from granting charters, remained aloof, while the overweening desire of those masterminding the venture was self-aggrandisement. Success was never certain and came about not through a deliberate far-sighted policy, but through a series of inter-locking accidents from which the English emerged as the survivors.

Read the rest here. So, although Elizabeth I is pictured in the Armada Portrait with her hand upon the globe of the earth to symbolize England's international power, she, like her Tudor predecessors, was not a great colonist or supporter of exploration of the New World (dare I say she was insular?). Image credit.

Published on March 28, 2014 22:30

March 27, 2014

Sunday Evening at St. Ambroise

In search of some coffee, something sweet, and some people watching, we walked down the street to Rue Voltaire on Sunday during our Paris visit, and found L'Eglise de St. Ambroise:

St. Ambroise was built between 1863 and 1868 and was consecrated on December 7, 1910. I'm not sure why there was such a gap between construction and consecration--the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune and its aftermath?--but it was consecrated on the patron saint's feast day (St. Ambrose of Milan)! The architect, Theodore Ballu, also designed St. Trinite and led the reconstruction efforts on Tour St. Jacques. Inside, we found beautiful stained glass and one most wonderful side chapel:

As you might suppose, there were stained glass windows depicting St. Augustine of Hippo, St. Ambrose's most famous convert, and St. Monica. The chapel dedicated to Our Lady contained beautiful stained glass windows (and there a matching chapel dedicated to St. Joseph):

Finally, my husband took this artistic shot of the shadows and the sunset (please note all these photographs are (C) Mark U. Mann, 2014):

We did find a cafe on the corner next to the church and enjoyed some treats and lots of people watching. There was a couple and a friend, I presumed, sitting and chatting at one of the cafe tables while their little girl played with a little plastic doll with long yellow hair. She kept dunking the doll in her glass of water--I'm not sure what she was trying to get out of the doll with such torture. We watched one family wheel their luggage by our table and go down the steps of the St. Ambroise metro (line 9). The father lagged behind, checking on something in the pocket of his suitcase while the mother and daughter waited at the top of the steps. Perhaps they'd been visiting relatives in the area and were heading off to Gare de Lyon for a train ride on the TGV home in the south of France? Other families rose up from the metro, and walked by the cafe with babies in carriages, dogs on leashes, and children in hand, going home after their Sunday excursions. Eventually we walked back to our apartment after experiencing an early Sunday evening in a Parisian neighborhood--nary a word of English around us.

St. Ambroise was built between 1863 and 1868 and was consecrated on December 7, 1910. I'm not sure why there was such a gap between construction and consecration--the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune and its aftermath?--but it was consecrated on the patron saint's feast day (St. Ambrose of Milan)! The architect, Theodore Ballu, also designed St. Trinite and led the reconstruction efforts on Tour St. Jacques. Inside, we found beautiful stained glass and one most wonderful side chapel:

As you might suppose, there were stained glass windows depicting St. Augustine of Hippo, St. Ambrose's most famous convert, and St. Monica. The chapel dedicated to Our Lady contained beautiful stained glass windows (and there a matching chapel dedicated to St. Joseph):

Finally, my husband took this artistic shot of the shadows and the sunset (please note all these photographs are (C) Mark U. Mann, 2014):

We did find a cafe on the corner next to the church and enjoyed some treats and lots of people watching. There was a couple and a friend, I presumed, sitting and chatting at one of the cafe tables while their little girl played with a little plastic doll with long yellow hair. She kept dunking the doll in her glass of water--I'm not sure what she was trying to get out of the doll with such torture. We watched one family wheel their luggage by our table and go down the steps of the St. Ambroise metro (line 9). The father lagged behind, checking on something in the pocket of his suitcase while the mother and daughter waited at the top of the steps. Perhaps they'd been visiting relatives in the area and were heading off to Gare de Lyon for a train ride on the TGV home in the south of France? Other families rose up from the metro, and walked by the cafe with babies in carriages, dogs on leashes, and children in hand, going home after their Sunday excursions. Eventually we walked back to our apartment after experiencing an early Sunday evening in a Parisian neighborhood--nary a word of English around us.

Published on March 27, 2014 22:30

March 26, 2014

The Queen and I: A Supremacy and Survival Interview

Beth von Staats, owner and administrator of the Queen Anne Boleyn Historical Writers blog and I got in contact because of one of her posts on the English Historical Fiction Writers, on Elizabeth Barton, the Holy Maid of Kent. we exchanged comments and then emails about the Catholic martyrs of the English Reformation, and why Elizabeth Barton hasn't been included among those beatified or canonized. We discussed some other aspects of the English Reformation, and Beth offered to interview me for the QAB blog.

Beth von Staats, owner and administrator of the Queen Anne Boleyn Historical Writers blog and I got in contact because of one of her posts on the English Historical Fiction Writers, on Elizabeth Barton, the Holy Maid of Kent. we exchanged comments and then emails about the Catholic martyrs of the English Reformation, and why Elizabeth Barton hasn't been included among those beatified or canonized. We discussed some other aspects of the English Reformation, and Beth offered to interview me for the QAB blog.Here is that interview, which Beth illustrated with excellent portraits from the Tudor era to the nineteenth century. I enjoyed answering all of her questions, and was particularly happy to address this major issue about the reign of Mary I and the efforts of Reginald Cardinal Pole to re-establish the Catholic Church in England:

7. I was fascinated by your accounting of Mary Tudor’s and Archbishop Reginald Pole’s attempted counter-reformation. Can you share with readers and browsers why you believe they were unable to meet their goals in shifting England and Wales back to Roman Catholicism?

I think it was a matter of time: they just did not have enough. They were successful in many of their endeavors. After I wrote S&S, Eamon Duffy published his Fires of Faith: Catholic England under Mary Tudor in which he details Pole’s catechetical, administrative, apologetic, and reform efforts. They were working, but when both Mary and Pole died the same day, the progress really ended. Elizabeth I was able to remove all the Catholic bishops Pole had appointed: only one of them would accept the new religious settlement passed by Parliament. The Convocation of Bishops had met and affirmed Catholic doctrine and therefore, this time, they did not swear the oaths of supremacy and uniformity. They were placed under house arrest, and the Marian exiles returned to replace them.

And, of course, I'm always thrilled to talk about Blessed John Henry Newman and the Oxford Movement:

12. I was exceptionally fascinated with the resurgency of Roman Catholicism in England and Wales in the 19th and 20th centuries. Just how much of an influence and impact was John Henry Newman towards this aim?

He was a great influence and he is also the symbol of that resurgence since he was a convert to Catholicism from the Church of England. He became a Catholic just 16 years after Catholics had been emancipated and just five years before the restoration of Catholic hierarchy in England, with new bishops, dioceses, churches, convents, monasteries, schools, etc being started and built up. As he famously said, it was a Second Springtime for the Catholic Church in England. There was still prejudice and fear of Catholics in England, and he often helped explain Catholic Church teaching. He influenced other converts, including many in the 20th century.

13. What is the Oxford Movement? Why did it result in the divisions seen within the Anglican Communion today?

The Oxford Movement or the Tractarian Movement was an attempt to remind Englishmen that their Church was more than just a part of the State; Newman, Froude, Keble, Pusey and others wanted to convince Anglicans that the bishops of the Church of England had real authority, handed down from the Apostles, not just controlled by Parliament. It began when Parliament proposed to close down Church of Ireland dioceses. The Tractarians, as they became known (because they published the “Tracts for the Times” presenting their views) thought the Church should make those decisions. In some ways, the Oxford Movement reflected on divisions that had existed in the Church of England for a long time: High Church (like the Caroline divines, Laud, Andrewes, etc); Low Church (the Puritans), and Broad Church (the eighteenth century Latitudinarians). Once Newman and many of his followers left the Oxford Movement, it developed into a liturgical movement, emphasizing more sacramental views of the Book of Common Prayer, introducing candles, incense and vestments into services (again, reviving Laudian reforms)—Anglo-Catholicism (John Shelton Reed wrote Glorious Battle: The Cultural Politics of Victorian Anglo-Catholicism, a fascinating study of the era. I am not sure if the Oxford Movement contributed to the divisions we see today or if it was a manifestation of those divisions in the Victorian era, dating from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Read the rest here and browse around the blog, which has many great book reviews and will feature an interview with Jessie Childs in the near future, to discuss her new book, God's Traitors: Terror & Faith in Elizabethan England.

Published on March 26, 2014 22:30

March 25, 2014

Rumer Godden's Brede and Dame Gertrude More

Dorothy Cummings McLean reviews Rumer Godden's In This House of Brede for Crisis Magazine:

Dorothy Cummings McLean reviews Rumer Godden's In This House of Brede for Crisis Magazine:Novels are what we read when we should be reading something else—or are they? Currently I should be reading Henri Nouwen’s “modern spiritual classic,” The Way of the Heart: The Spirituality of the Desert Fathers and Mothers, but in fact I have just finished Rumer Godden’s novel, In This House of Brede. And I feel no embarrassment in saying that the laywoman’s novel taught me far more about the way of the heart than the priest’s meditations. After decades of preaching the virtues of a low fat diet, nutritionists now tell us our dietary culprit isn’t fat. Apparently we have always needed good fat in our diet. Godden’s novel runs with rich oils; Nouwen’s book strikes me as sugary.

I first heard of In This House of Brede when I went to the Solemn Profession of a young nun to the Abbey of Saint Cecilia at Ryde on England’s Isle of Wight. Saint Cecilia’s, I was told, was one of the models for Rumer Godden’s fictional Brede. As my visit to the abbey was one of the most edifying trips of my life, showing me how beautiful enclosed life can be, I resolved to read this book.

The abbey Godden more closely based her work on was Stanbrook Abbey, which is now in a different location than when she knew it, but has its roots in the English exiles of the Reformation and Recusant eras, who founded the house in Cambrai. One of the founders was St. Thomas More's great-great-granddaughter, Helen More--Dame Gertrude More in religion:

St Thomas More's great-great-granddaughter, Helen, left England at the age of seventeen as a key figure in a new venture: the foundation of a monastery for Englishwomen under the aegis of the English Benedictine Congregation. Suitable, though dilapidated, buildings were found in the city of Cambrai. There, together with two of her More cousins and six other young Englishwomen, Helen was clothed in the Benedictine habit on 31 December 1623 and professed as Dame Gertrude on 1 January 1625. The monastery of Our Lady of Consolation, now at Stanbrook Abbey, Wass, had come into being.

Dame Gertrude herself was utterly miserable. A lively extrovert, she was not born to a life of prayer and had not particularly wanted to enter a monastery, though she had kept that to herself. She tried to read spiritual books, consult different confessors, but in vain. In November 1625 she was so desperate that she went to the man she had hitherto ridiculed, Father Augustine Baker.

Within a fortnight her life was changed. What had seemed impossible was 'made by him so easy, and plain,' she recalled. Once she had learnt to put aside self-will, she was free to recognize God's voice, the 'call' or prompting of the Holy Spirit in her heart. Her fear and despair gone, Dame Gertrude was at last flying 'freely with wings of Divine love'.

I certainly agree with McLean that Godden's novel is a masterpiece. I read nearly all of Godden's books and always appreciated her excellent story-telling and sometimes adventurous technique, usually dealing with time and place (Take Three Tenses: A Fugue in Time; China Court: The Hours of a Country House, etc). Little, Brown has been re-issuing some of her novels in paperback with new covers as part of the Virago Modern Classics series.

Published on March 25, 2014 22:30

March 24, 2014

Good Friday, March 25, 1586

U.K.'s The Catholic Herald highlights St. Margaret Clitherow, crushed to death on March 25, 1586 for refusing to make a plea in her arrest for harboring a Catholic priest in York:

U.K.'s The Catholic Herald highlights St. Margaret Clitherow, crushed to death on March 25, 1586 for refusing to make a plea in her arrest for harboring a Catholic priest in York:Margaret was arrested in 1586 for harbouring Catholic clergy. She refused to plead guilty to the charge because she knew her children would be brought forward as witnesses and consequently might be subjected to torture.

Margaret was executed by being crushed to death on Good Friday in 1586. The two sergeants hired to kill her used four beggars to do the deed instead. It took her 15 minutes to die as she was crushed with rocks and stones. Her last words were “Jesu! Jesu! Jesu! have mercy on me!”

Her body was left for six hours until the weight was removed. Her hand was saved following her death and is now a relic in the chapel of the Bar Convent in York.

When Elizabeth I heard of Margaret’s horrific death, she wrote to the citizens of York condemning the act and arguing that women should not be executed. Her son William also became a priest and her daughter Anne became a nun in Louvain, Belgium. Margaret was beatified in 1929 by Pope Pius XI and canonised in 1970 by Pope Paul VI. She is one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

When St. Margaret Clitherow was prepared for her execution, she was laid on her back with a sharp stone underneath. Her arms were spread and tied down as though she was on a cross, with her feet tied down. Did her executioners realize that she was imitating Jesus on the Cross so exactly, on Good Friday?

Published on March 24, 2014 22:30

March 23, 2014

Marching Forth in the Marais

On our way to the Musee de la Carnavelet (which was closed "extraordinaire" when we got there) we stopped at Le Sevigne near Parc Royal and Square George Cain for espresso and cafe au lait, served with d'eau in those little glasses. Even before we arrived at this charming cafe we saw the signs of Spring--particularly the herald of spring: forsithia.

Then in Square Georges Cain, among ruins from the Tuileries Palace, we saw the planted beds of flowers:

As we walked further into the Marais, we passed this oriel structure, built in the seventeenth century so members of the household could watch passersby from above:

As we walked further into the Marais, we passed this oriel structure, built in the seventeenth century so members of the household could watch passersby from above:

Finally, we could see St. Paul-St. Louis on Rue St. Antoine in the distance:

Inside, after I don't know how many visits and attempts, I think I finally took a good picture of Delacroix's Christ in the Garden of Olives:

Inside, after I don't know how many visits and attempts, I think I finally took a good picture of Delacroix's Christ in the Garden of Olives:

Published on March 23, 2014 22:30