Angela Slatter's Blog, page 19

February 21, 2020

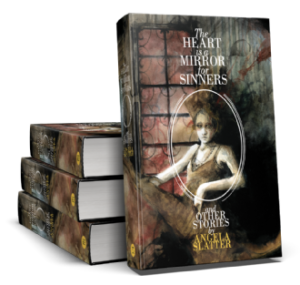

New Collection: The Heart is a Mirror for Sinner and Other Stories

My new collection from PS Publishing is available for pre-order! The Heart is a Mirror for Sinners and Other Stories has 14 stories (12 reprints and two new), and an Introduction from the marvellous Mr Kim Newman.

My new collection from PS Publishing is available for pre-order! The Heart is a Mirror for Sinners and Other Stories has 14 stories (12 reprints and two new), and an Introduction from the marvellous Mr Kim Newman.

The ToC:

Tin Soldier

Egyptian Revival Neither

Time Nor Tears

No Good Deed

The Little Mermaid, in Passing

But for an L

Ripper

Better Angels

The Heart is a Mirror for Sinners

Our Lady of Wicker Bridge

Reading Off the Curriculum

Change Management

Lavinia’s Wood

Finnegan’s Field

Praise for The Heart is a Mirror for Sinners and Other Stories:

‘Slatter’s dark fantasies have a bright, burning core of understanding and insight.’ ~ M.R. Carey, author of The Girl with All the Gifts and The Boy on the Bridge

‘Angela Slatter’s stories are horrific, mysterious, whimsical, and mischievous. Beautifully written, full of humanity and intelligence, her stories are both timely and timeless in their concerns. This is an essential collection from one of our best.’ ~ Paul Tremblay, author of A Head Full of Ghosts and The Cabin at the End of the World

‘Angela has a rare talent for drawing the reader into her world, with a lyrical, almost fairytale quality to her writing that also shows a sardonic wit to delight the reader. This collection showcases some of her best stories—you need to read it.’ ~ Marie O’Regan, author of Bury Them Deep, editor of Phantoms and The Mammoth Book of Ghost Stories by Women

‘Angela Slatter’s prose is both eloquent and elegant, which is no mean feat. By turns beautiful and chilling in equal measure, her stories feature characters who live and breathe and leap off the page, while the plots themselves are wholly unique. This book is a gem and you should treasure it as such.’ ~ Paul Kane, bestselling and award-winning author of Sherlock Holmes and the Servants of Hell, Monsters, and Before

February 11, 2020

Women in Horror Month

Art by Kathleen Jennings

Good morning from my Terribly Neglected Blog.

For Women in Horror Month here are a couple of useful links. Firstly Kat Clay has compiled a list of horror stories by Australian writers (who just happen to be female). Go here.

And another lovely list of horror writers who also happen to be female from Gwendolyn Kiste at Tor’s Nightfire site.

January 15, 2020

Time Moves Differently Here

Art by Kathleen Jennings

The thing about writing a book is that it takes so long. And this is not a complaint, merely an observation. This is my personal experience.

Bookering, bookerisation, bookification …

From the first tiny spark that you breathe life into to that moment when you’re seeing it on shelves … it takes quite a while.

Firstly you’ve got to think about it.

Then you’ve got to start writing it.

Then you’ve got to finish it.

Then you’ve got to edit it.

Then you have to find a publisher who likes it.

Then someone else has to edit it.

Then you’ve got to re-edit it while setting aside your ego, insecurity, doubts, insanity and periodic urges to shout “You maniacs, you blew it all up!” whilst shaking your fist at the sky.

Then you send it back to the publisher.

And maybe they send it back again.

And then you go over this thing again – this thing that was your most beautiful and favoured child, but which you’re starting to suspect is instead a changeling left lying in the cradle by trolls or fairy folk just to fuck with you – and then you send it back again.

And then, maybe it doesn’t come back again.

Because just maybe it’s ready … or as close as it’s ever going to be in this world and the next.

So then you’re on to looking at cover designs (if you’re lucky you get asked which artists you’d like, and if you’re not lucky then oftentimes you’re really not lucky).

And then you’ve got to ask people you admire to say nice things about your book for the cover quotes (and that’s a special circle of Hell right there, sadly neglected by Dante).

And then you’ve got to write (if you haven’t done it prophetically back in the Beginning of All Things) a jacket summary for the book, to make either a novel or a bunch of disparate stories look enticing. Sometimes that feels very much like you’re putting lipstick and a peignoir on a rather large show pig.

And then you’re almost there and your publisher says “We’re almost there!”

Then you realise you need to update your bio, and as you’ve been doing this gig for longer and longer, your bio gets longer and longer, but you’ve got to Sophie’s Choice your favourite babies … and suddenly achievements that felt like a lightning strike seven years ago suddenly look a bit cobwebby and you feel unutterably sad (but you’ll probably utter it anyway coz writer) … and then you ruthlessly rework your bio with a sense of nostalgia that makes you a little ill …

And then you’ve got to find your author photo, which in my case is 12 years old and I actually look like 72 chipmunks in a trench coat nowadays, and I know I need to replace it but I’ll still go with the old photo for a while longer (read: deathbed) …

Here’s another thing:

The above doesn’t mention the stuff in life that will throw you off course: love, death, day job, time spent with pets, partners and offspring, breakups and breakdowns, roof cave-ins (actual and metaphorical), bushfires, heavy snowfalls, floods, writer’s block.

The above doesn’t even factor in the delays that are out of your control: happenings in the life of your editor/publisher that throw them off course. Anything from pet surgery to bankruptcy, from broken limbs to scandals of all hues.

But then one day, it’s ready. And then everything’s urgent. So you have to put aside the new book you’re working on and go back to thinking about the old one, which has become a bit like the kid you fondly sent off to boarding school or put on a tramp steamer for a trip around the world some time ago … and suddenly they demand your attention again.

And again, this is not a complaint.

This is a summary of how it happens for me, every time. This is something new and hopeful writers (who’ve not yet developed a thousand-yard stare) can read and take pointers from to help them manage their expectations. They’ll need it if they keep on this thorny, burning, chocolate-strewn, whisk(e)y-flooded path.

It’s different for other writers, of course it is.

But this can give you some idea of what it might be like.

My point?

It’s a long game.

It takes patience.

A thick skin.

A warm coat and heavy boots for those terrible Russian winters of the soul.

A doomsday prepper-level stash of chocolate and whisk(e)y to help you get by.

And all this was spawned because my next collection is almost ready and is demanding my attention. And I had to rewrite my bio. And look at that ancient author photo and say “Yeah, one more year”. And thank Past Me who had already written a summary two years ago. And be grateful that I also sought out author quotes two years ago so my soul isn’t burning with that particular shame today at least. And be so darned grateful that when I work with PS Publishing they ask me who I want as a cover artist and they listen and that Daniele Serra did the most beautiful illustrations based on my novella Ripper.

Anyhoo, that’s just my day so far.

May your path be strewn with good things as well as bad, and eighteenth-century fainting couches at reasonable intervals along the way for dramatic sighing and crying, general pausing and power naps.

Cover art by Daniele Serra

So if your instinct is to bitterly say “Well, at least your books are published”, then can I suggest that you don’t read any further? The door is over there, don’t let it hit you on the way out. This post isn’t meant for you.

January 2, 2020

The Dark Issue 56

A lovely way to start the year is with a reprint in The Dark, issue 56! My story “No Good Deed” (a tale set in the world of the Sourdough and Bitterwood mosaic collections) is alongside wonderful work by Clara Madrigano, Ray Cluley and Steve Rasnic Tem.

A lovely way to start the year is with a reprint in The Dark, issue 56! My story “No Good Deed” (a tale set in the world of the Sourdough and Bitterwood mosaic collections) is alongside wonderful work by Clara Madrigano, Ray Cluley and Steve Rasnic Tem.

Go here!

Isobel hesitates outside the grand door to the chamber she’d thought to share with Adolphus. It’s a work of art, with carven figures of Adam and Lilith standing in front of a tree, a cat at the base, a piece of fruit in transit between First Man and First Woman so one cannot tell if she offers to he, or otherwise.

Her recent exertions have drained what little strength she had, and the food she’d found in the main kitchen (all servants asleep, the odour of stale mead rising from them like swamp gas) sits heavily in a stomach shrunk so very small by a denial not hers. The polished wooden floorboards of the gallery are cold beneath her thin feet—so thin! Never so slender all her life. A little starvation will do wonders, she thinks. As she moved through the house, she’d caught sight of herself in more than one filigreed mirror and seen all the changes etched upon her: silver traceries in the dishevelled dark hair, face terribly narrow—who’d have known those fine cheekbones had lain beneath all that fat?—mouth still a cupid’s-bow pout and nose pert, but the eyes are sunken deep and, she’d almost swear to it, their colour changed from light green to deepest black as if night resides in them. The dress balloons around her new form, so much wasted fabric one might make a ship’s sail from the excess.

How long before the plumpness returns? Before her cheeks have apples, the lines in her face are smoothed out? She can smell again, now, but all she can discern is the scent of her own body, unwashed for so long. A bath, she thinks longingly, then draws her attention back to where it needs to be: the door.

Or, rather, what lies behind it.

December 5, 2019

THE BEST OF SHIMMER

I’m absolutely delighted to say that I’ve got a story in this lovely tome, THE BEST OF SHIMMER, coming in 2020.

I’m absolutely delighted to say that I’ve got a story in this lovely tome, THE BEST OF SHIMMER, coming in 2020.

As “The Little Match Girl” was my first real sale when I started writing, I’m so happy she’s reprinted in this anthology.

ToC:

Flying and Falling, by Kuzhali Manickavel

Little Match Girl, by Angela Slatter

Skeletonbaby Magic, by Kathy Watts

King of Sand and Stormy Seas by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

The Crow’s Caw, by Amal El-Mohtar

Juana and the Dancing Bear, by n.a. bourke

Birds and Burin, by Daniel A. Rabuzzi

The Shape of Her Sorrow, by Joy Marchand

Seek Him I’th’Other Place Yourself, by Josh Storey

Five Letters from New Laverne, by Monica Byrne

Gutted, by Lisa Hannett

Some Letters for Ove Lindström, by Karin Tidbeck

Gödel Apparition Fugue, by Craig DeLancey

Food My Father Feeds Me, Love My Husband Shows Me, by A. A. Balaskovits

Ordinary Souls, by K.M. Szpara

In Light of Recent Events I Have Reconsidered The Wisdom of Your Space Elevator, by Helena Bell

Like Feather, Like Bone, by Kristi DeMeester

We Were Never Alone In Space, by Carmen Maria Machado

The Earth and Everything Under, by K.M. Ferebee

A Whisper in the Weld, by Alix E. Harrow

The Half Dark Promise, by Malon Edwards

Dharmas, by Vajra Chandrasekera

Come My Love and I’ll Tell You a Tale, by Sunny Moraine

Serein, by Cat Hellisen

The Law of the Conservation of Hair, by Rachael K. Jones

Palingenesis, by Megan Arkenberg

Red Mask, by Jessica May Lin

All the Colors You Thought Were Kings, by Arkady Martine

Painted Grassy Mire, by Nicasio Andres Reed

Only Their Shining Beauty Was Left, by Fran Wilde

Itself at the Heart of Things, by Andrea Corbin

The Creeping Influences, by Sonya Taaffe

Hare’s Breath, by Maria Haskins

The Weight of Sentience, by Naru Dames Sundar

Black Fanged Thing, by Sam Rebelein

The Triumphant Ward of the Railroad and the Sea by Sara Saab

Faint Voices, Increasingly Desperate, by Anya Johanna DeNiro

Rapture, by Meg Elison

Lake Mouth, by Casey Hannan

From the Void, by Sarah Gailey

The Time Traveler’s Husband, by A. C. Wise

Rust and Bone, by Mary Robinette Kowal

Ghosts of Bari, by Wren Wallis

November 28, 2019

Ladies of the Fright: Witches!!

Art by Kathleen Jennings as always, from Flight.

Over Halloween I had a chat with the delightful and delovely Lisa Quigley and Mackenzie Kiera, the Ladies of the Fright! About witches (or my “witch work”). Me, sounding very Australian – in the background you can hear grumbling dogs, in both Brisbane and New York.

“Show me your witches and I’ll show you how you how you feel about your women.” Pam Grossman

We talk fairy tales, witchy stuff, a potted history of witches, that witches weren’t always unjustified in what they did, and we discuss in depth the magnificent “These Deathless Bones” by Cassandra Khaw … and my recommended reading list is below.

Go here!

Witches Book Recommendations

Fiction

Emma Donoghue’s Kissing the Witch

Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber

Anne Rice’s The Witching Hour

Tanith Lee’s The Blood of Roses and The Flat Earth Series

Lisa L. Hannett’s Bluegrass Symphony

Naomi Novik’s Uprooted

https://bookriot.com/2017/04/18/100-must-read-books-witches/

Non-fiction:

Marina Warner’s From the Beast to the Blonde

Stacy Schiff’s The Witches: Salem 1692

Elizabeth Lynn Linton’s Witch Stories (you can get this on Project Gutenberg)

Authors to look out for:

Angie Rega

Suzanne J. Willis

Shauna O’Meara

Leife Shallcross

Kirstyn McDermott – argh! How could I forget this one? https://www.tor.com/2018/09/05/triquetra-kirstyn-mcdermott/

Nin Harris

Silvia Morena-Garcia

Tonya Liburd

Maria Lewis

Vida Cruz

Theodora Goss

Maria Haskins

Gwendolyn Kiste

Karen Runge

November 14, 2019

Scribbles

In between a million other things, I’m trying to make sure I keep writing my own things … they make me feel happy, grounded when the world is a bit topsy-turvy (like now, end of year, moving house, deadlines, etc). So here is my current scribble, untitled (but let’s call it “Nest” for the moment), but I think it might be the Welsh ghost story I’ve been wanting to write for some time … Plus a bit of Kathleen Jennings art as eye candy …

White fox by Kathleen Jennings (not a puppy)

“Nest”

Nest’s father used to tell her that her mother had been stolen away by the fairies. That Aderyn had gone looking for mushrooms either too early one morning or too late one afternoon. Owain wasn’t entirely clear, only certain that his wife been taken through either daylight or twilight gate.

By the time Nest had grown old enough to question him about it Owain himself was gone; not physically, but mentally. He wandered in his thoughts, so that he didn’t spend many hours in the cottage nestled into the crook of the hill. He’d tell his daughter he was roaming even while she could see him in front of her, firmly settled in the worn old armchair, a cast-off from somewhere. Owain would have slept there, too, if Nest hadn’t stubbornly sent him to his bed every night, no matter how exhausted she was herself. He forgot to feed himself much of the time, but would obediently open his mouth if Nest or Mrs Collins the neighbour sat before him with spoon and bowl. And some days he did leave the house, some days he slipped out the door ? before his daughter began to stay home and take in spinning so she could keep a watchful eye on him ? and wander the valleys and peaks. Once, Owain disappeared for two entire days; Nest all but lost hope of finding him again, but she couldn’t deny that spark of relief at the idea of being freed of her watch. But Daffyd Morgan found him, didn’t he, and brought him home again; Owain strangely silent about where he’d been for once.

Any road, Aderyn was gone before Nest had anything more than cloudy memories of a narrow pretty face, dark eyes, blacker than black hair, and a red birthmark running up the side of her throat.

November 3, 2019

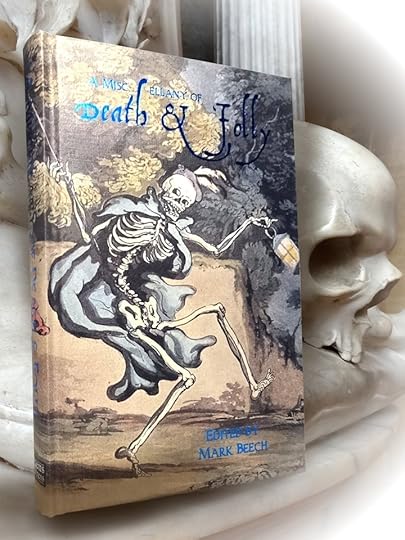

A Miscellany of Death & Folly

A Miscellany of Death & Folly

is now available to order!

A Miscellany of Death & Folly

is now available to order!… An entertainment including works from some of the finest authors of the weird and morbid working today: A collection of admirable knick-knacks and curios, fictions, non-fictions, poems, for your amusement.

It isn’t intended to depress or distress, to trigger or traumatize. It doesn’t condone ghoulish, maudlin or destructive attitudes. It simply is… A dismal, witty, pretty, weird trifle of a thing on which, dear reader, I hope you enjoy passing a little time in the run of this absurd, overlighted dream we call human life.

The full table of contents is as follows:

THE BONE-CAGE BLUES by Cate Gardner

THE CRYPT OF YEDDI GUMBAZ by Albert Power

DEATH HAIKUS by David Yates

SZÉKELY’S LAST PLATE by D.P. Watt

TARTINI’S FINAL DREAM by Chris Kelso

DEATH AND THE BALLADRESS by Adam Bolivar

THE PROMISE OF SAINTS by Angela Slatter

GENTILE FANCIULLACCI PASOLINI by Paul StJohn Mackintosh

DARKNESS by Ismael Espinosa (translated by George Berguño)

DEATH BECOMES HER by Icy Sedgwick

ANODYNE SOLUTIONS by Kaaron Warren

ALL THE WILD ANIMALS by Brendan Connell

A MONUMENT by Adriana Díaz Enciso

PROFIT AND LOSS by Hayden Peters

BLACKHEARTS AND SORROWSONG by Suzanne J. Willis

EDWIN’S CURSE by Kayleigh Marie Edwards

The book is a lithographically printed, 250 page sewn hardback with colour endpapers; limited to just 300 copies.

For more details and to order visit: http://www.egaeuspress.com/Death_&_Folly.html

October 29, 2019

For a Halloween Snack

Stephen J. Clark’s “Homunculus”

Here’s my short story “Sourdough” …

Sourdough

by Angela Slatter

My father did not know that my mother knew about his other wives, but she did.

It didn’t seem to bother her, perhaps because, of them all, she had the greater independence and a measure of prosperity that was all her own. Perhaps that’s why he loved her best. Mother baked very fine bread, black and brown for the poor and shining white for the affluent. We were by no means rich, but we had more than those around us, and there was enough money spare for occasional gifts: a book for George, a toy train for Artor, and a thin silver ring for me, engraved with flowers and vines.

The sight of other children in other squares, with Father’s uniquely gleaming red hair, did not bother Mother at all. After he died, I think she found it comforting, to be reminded of him by all those bright little heads.

Our home was in one of the squares at the edge of the merchants’ quarter – the town was divided into ‘quarters’ that weren’t really quarters. Seen from above, the town.

It was a large square, made up of groups of much smaller squares (tall houses built around a common courtyard); in the centre of the town was the Cathedral, high up on a hill, then spreading around it in an orderly fashion were rows and rows of city blocks, the richest ones nearest the Cathedral, then the further out you got, the poorer the blocks. We sat just before the poorest houses, not quite good enough to be in the middle of the merchants’ rows, but still not in among the places were rats shared cradles with babies. We had several large rooms mid-way up one of the tall houses, and Mother leased out the big ground-floor kitchen for her business.

From the time I could walk I would follow Mother around the kitchen, learning her art. For a while she was simply annoyed by my constant presence, as I got under foot, but when I learnt to sit on the bench next to the huge wooden table on which she kneaded the bread, and be quiet, she decided to share her knowledge. I was her firstborn, after all, and her only daughter.

When I could see over the top of the table, I started to help her. Baking tiny child’s loaves at first for practice, much to Mother’s amusement, then making the dark, ‘poor’ bread for those who could not afford refined flour. Finally, I was allowed to create white bread to grace the tables of the rich: those born to wealth and knowing nothing else, the higher merchants, the bishop and his like. I began to create complicated twists of dough to look like artworks. At first Mother laughed, but the orders kept coming for them, so she watched and imitated me.

One morning, after we’d finished baking for the day, I began to play with the leftover dough on the board in front of me. Soon a child formed, a baby perfectly copied to the life, with tiny hands and feet, an angel’s smile and a sculpted lick of hair on its forehead.

Mother came up behind me and stared. She reached past me and squashed her fists down on the dough-child, pushing and kneading until it was once again a featureless lump.

‘Never do that. Never make an image of a person or a child. They bring bad luck, Emmeline, or things you don’t want. We don’t need any of that.’

I should have remembered the dough-child, but memory is a traitor to good sense.

#

There was to be a wedding, arranged, a fine society ‘do’ and we were to supply the bread.

The parents of the groom – or rather, his mother – insisted on being involved in every decision pertaining to the wedding, so there was a power struggle in train between her and the bride’s mother (two titans in boned bodices). Things were getting tense, apparently – this information we had from Madame Fifine (about as French as Yorkshire pudding), the confectioner who was to supply the bonbons for the wedding feast. We were to appear at the groom’s parents’ house, goods in tow, to show our wares.

Mother and I tidied ourselves as well as we could, pulling flour-free dresses from chests and piling our hair high. Artor and George were press-ganged into carrying the wooden trays of our finest white breads to the big house near the Cathedral. We were shown into a drawing room almost as big as our ground-floor kitchen.

As soon as the boys gingerly laid the trays on the big table, Mother shooed them out. I knew they’d be in the stableyard, bumming cigarillos from the stable and kitchen lads, eyeing the horses longingly, waiting for the day when Mother could afford a horse and carriage (that day was a long way off, but they hoped the proceeds from the wedding would speed up the process).

The drawing room was awash with boredom. The parents sat stiffly across from each other on heavily embroidered chairs whose legs were so finely carved it seemed that they should not be able to support the weight of anyone, let alone these four who almost dripped with the fat of their prosperity. The bride, conversely, was thin as a twig, nervous and sallow, but pretty, with darting dark eyes and tightly pulled hair sitting in a thick, dark red bun at the base of her neck. The groom did not face the room: he had removed himself to the large French window and was staring at the courtyard below (probably watching my brothers watching his horses). He had dark hair, curly, that kissed the collar of his jacket, and he was tall but that was all I could tell. Madame Fifine had said he was called Peregrine.

Mother nodded to me and I took the first loaf from one of the trays, showed it to the clients so they could observe its clever shape (a church bell with bows), then placed it on a platter and cut six slices for them to taste. The two mothers, the two fathers, the bride all took their slices and the room was silent but for their well-bred chewing. I crossed the room and offered the groom the last slice. He didn’t turn, merely raised his hand in a ‘no’ and shook his head. I noticed his hand bore the stain of a port-wine birthmark.

‘It would be a shame, sir, to waste something so fine.’

Perhaps struck by the fact that I spoke to him, he looked at me and broke into a smile.

‘Yes. You’re right. It would be a shame.’ He took the bread, green eyes bright. ‘What hair you have, miss.’

I blushed.

‘Emmeline.’ Mother called me and I began my task over again: now the loaf shaped like a flower, now the one like an angel, now all the animal shapes (rabbits, doves, kittens, a horse), the one like a church. Each time I saved his slice until last and we spoke in low voices, he asked me about my life and laughed at my pert answers. When the tasting was finished, the mothers began to argue; the design to choose was the cause of combat. Finally, they turned to the girl, Sylvia, and made her decide. She had the look of a trapped animal and I felt sorry for her.

‘Perhaps…’ I began and all eyes turned to me, the mothers’ brimming with affront, the fathers’ with boredom, the groom’s with amusement, my own mother’s with something like dread, and the bride’s with hope of rescue. ‘Perhaps Miss Sylvia has a favourite animal or flower. We could make the bread to her choice if she does not like what we have brought today.’

‘A fox!’ she cried, clapping her hands to her mouth as if she had said something a-wrong or too bold. I smiled and she said more firmly. ‘Yes, a fox. That would please me.’

‘As you wish, Miss Sylvia.’ Mother’s voice was a relieved breeze. ‘My Emmeline can make anything with her hands; she has great skill.’

So it was settled. The bride had spoken, and defied both her mother and future mother-in-law. Mother and I hefted the wooden trays scattered with the remains of butchered loaves and made for the door. The groom was there before the footman and ushered us through. He smiled and I felt as warm as bread fresh from the oven.

#

In the months before the wedding he came to me many times.

The first time I was alone in the kitchen – Mother was ill, spending half her time sleeping the other half shouting delirious orders (which I ignored) from her bed. Artor and George took turns delivering the bread and sitting by her side, while I kept the kitchen running.

I dropped the tray when I saw him at the door. I was covered in flour, my hair covered by a scarf, and barefoot because I loved the feel of the kitchen flags cool and covered with a light dusting of flour. He laughed and held out the largest bunch of flowers I had ever seen. I examined it as he picked up the fallen tray and placed it on one of the benches. This was no posy picked from the fields outside the town, these were exotic blooms, blossoms grown in hothouses and afforded only by the rich.

‘Hello, Miss Emmeline. Are you baking for my wedding yet?’

‘That’s months off, young sir, as you well know. How would it look to serve stale bread at your wedding feast?’

‘It would be appropriate, more appropriate than you know. My fox bride might even tell you that herself, if she were truthful.’ He touched one of the florid roses in the bouquet and smiled. ‘Do you like these?

‘They are very fine, sir. Fit for your bride.’

‘But I think you will like them best.’

‘Yes.’

We did nothing more, that first time, than talk. Subsequent times were very different, but that first visit, I think, made us friends and stood us in good stead. He brought gifts, even though I told him not to; something for me always, sometimes things for Mother and the boys. Artor and George, hostile and suspicious at first, were won over when he brought the horses. Two of the finest creatures I’ve ever seen, with a red-gold fleck to their coats and white stars on their foreheads. Peregrine told me later that their colouring reminded him of our bright hair. The most beautiful thing he gave me was a ring, rose-gold with a square-cut emerald.

‘A dangerous stone,’ I told him.

‘What do you mean?’

‘An emerald will crack, if given by a lover whose heart is unfaithful,’ I replied. He laughed and dragged me down.

‘Yours will be safe.’

I had no expectation of marriage – I was friend and mistress. He would marry his fox bride, as he called Sylvia, and I knew it. I only expected constancy and for many months I had it.

When my belly began to swell, he laughed with delight, his fingers lightly dancing over my taut skin, stroking the curls at the apex of my thighs, and gently showing me how pleased he was at what we had made together. I thought then, briefly, of the dough-child, but put it from my mind.

One day, a fortnight before his wedding, he ceased to visit. Instead, the fox bride came one morning as I kneaded dough in the kitchen.

She was different to the nervous girl I had met months ago. She eyed the kitchen – and me – with disdain, as if she might somehow find some uncleanness clinging to her silken skirts from the mere proximity of such a place and personage. I put my hands to my stomach. She snorted, a brief, sharp laugh that cut.

‘You will not have him anymore,’ she said. ‘He will be my husband.’

‘You do not love him,’ I replied. It had not occurred to me that the fox bride would not share.

‘But I want this marriage. I want to be away from my parents. I want to be mistress of my own house. But if he keeps running to you, keeps loving you more and more then he may decide not to marry me.’ She glared. ‘I will not allow that to happen.’

‘Stay away from here. Stay away from me. I will tell him.’

‘He does not remember you.’ She laughed, came close, and showed her sharp white teeth in a smile. ‘Why do you think he isn’t here? With his love, watching what he’s planted grow? You’re not the only one who can make things; potions are more powerful than bread, little Emmeline.’

Her hand shot out and she laid her palm against my belly. I moved back, almost falling over an uneven flag. ‘Watch nothing goes into your food, Emmeline. You wouldn’t want to lose this last piece of Peregrine.’

I heard her laughter even as she walked down the street. I thought only to run to Peregrine, but my nose began to bleed and my belly contracted so hard that I did fall this time, and mercifully found the dark balm of sleep.

#

Their wedding day dawned grey and overcast as summer slipped into autumn. The weather kept all but the most enthusiastic of wedding goers at home – the old women who wait outside the church, knitting and yammering, commenting on all aspects of the event: how the bride looked, how well her dress suited (or not), if she was glowing and if so, why (honeymoon baby, my sainted aunt!), and how long the marriage would last.

It was with these ancient birds that I waited on the first day I had managed to leave my bed.

The child had come too soon, a little boy, looking not unlike the dough-child, and leaving me bereft. Mother had barely left my side, worrying that I would not speak, would not touch the still little body before she took it away. Artor and George brought me posies but they only made me cry. I missed the brief funeral that was held for my son, confined to bed by a bleeding the sad, gentle little doctor could not stop. Mother brought an old woman one night who gave me something foul to drink and applied a sweet-smelling poultice of moss between my legs. My body started to repair itself then.

Mother told me that the boys had tried to speak to Peregrine; he had simply looked at them in bewilderment, saying he did not know who they were. They had hidden the horses he had given them in a stable at the outer edges of town, in case someone accused them of theft. Mother had presented herself at the big house, ostensibly to discuss the wedding bread, and Peregrine simply looked through her. She felt that she must be a ghost, so empty was his face. The old woman who had tended to me told her there were things that could bewitch a man’s mind and make him forget his dearest desire.

The fox bride was more than she seemed.

I watched her as she left the Cathedral on her husband’s arm. I would have let her have this; it had never been my intent to take it from her, but she had stolen my lover and my child was dead. She stepped into a puddle of mud as she headed toward the carriage, and shrieked her distaste as her silk shoes and white lace hem turned the colour of dirty chocolate. I smiled in spite of myself and slid the hood from my head, my bright hair shining out in the dimness of the day. Peregrine looked up from his wife’s distress and saw me. His face twisted, distracted and uncertain, but he did not know me. His attention turned back to his bride and I slipped away before she could see me and triumph.

In my kitchen, I found the remnants of the wedding bread dough and began to sculpt another dough-child. I fashioned it as cunningly as the first but this time with intent and not a little malice. Such magic requires only intent and ill-will but no great skill.

I drew from my finger the ring Peregrine had given me. The emerald gleamed at me, intact, unbroken; his heart was never unfaithful, only his memory. The ring was pushed into the dough-child’s belly. I made a bellybutton to cover its ingress.

When it came from the oven, it had a fine golden crust and looked like a cherub. I delivered it to the cook at the house the newlyweds were to share; she was a friend of Mother’s and took the dough-child gladly.

‘Tell them it’s for fertility, to bless them with a child.’

She nodded. ‘They shall have it for supper this very eve, Emmeline.’

#

He told me later how the dough-child had been served to them on a silver tray, with butter and a selection of jams. Sylvia had ooh-ed and aah-ed over the silly little thing and happily cut herself a thick slice, slathering it with sugary conserve. Peregrine ate the bread dry and unadorned. When the sourdough touched his tongue his memory returned.

The fox bride continued to eat as he railed at her. She greedily chewed and swallowed great bites of bread, laughing at his rage and talking around her food, telling him she would do it again, too. Then she began to choke. Her face went red, then blue around the lips as she struggled to draw in air. She pointed at her throat, threw things at him as he stood, staring in horror. When she was finally still, he called for a doctor.

The little doctor, the one who had attended me so unsuccessfully, found the emerald ring lodged in her throat. He, I’m sure, recognised it and placed it in Peregrine’s hand, closing the young widower’s fingers around the piece of jewellery. ‘Someone will be looking for that, young man.’

I no longer wear it very often, knowing what I did with it, although I do bring it out now and then to remind myself of his constant heart. We live in another house, as far away from his parents as he could get, but still in one of the nicer squares. My mother runs her business out of a real shop not far from us, and has two young girls apprenticed to her.

‘They don’t have your touch, Emmeline,’ she sometimes says but she knows why I will no longer bake, why my hands will never again knead dough. She is happy, for she knows her grandchild comes. I am content to visit the small grave where my first child lies. I speak with him often and tell him about his father and sister, who comes to us soon. I tell him I am sorry I could not protect him and that I will never forget him. My memory is true.

‘They don’t have your touch, Emmeline,’ she sometimes says but she knows why I will no longer bake, why my hands will never again knead dough. She is happy, for she knows her grandchild comes. I am content to visit the small grave where my first child lies. I speak with him often and tell him about his father and sister, who comes to us soon. I tell him I am sorry I could not protect him and that I will never forget him. My memory is true.

###

“Sourdough” first appeared in Strange Tales II, (Rosalie Parker, ed.) Tartarus Press, December 2007, then again in Sourdough and Other Stories, Tartarus Press, 2010.

October 19, 2019

A MISCELLANY OF DEATH & FOLLY

A MISCELLANY OF DEATH & FOLLY will be available to order on November 2nd, Dia De Los Muertos (The Day of The Dead). I’m absolutely delighted to have a story in this book – Egaeus produces such exquisite collector’s editions!

A MISCELLANY OF DEATH & FOLLY will be available to order on November 2nd, Dia De Los Muertos (The Day of The Dead). I’m absolutely delighted to have a story in this book – Egaeus produces such exquisite collector’s editions!

A frivolous little volume, it will feature all manner of literary delights from:

Cate Gardner

Albert Power

David Yates

D.P. Watt

Chris Kelso

Adam Bolivar

Ismael Espinosa (translated by George Berguño)

Icy Sedgwick

Kaaron Warren

Angela Slatter

Paul StJohn Mackintosh

Leena Likitalo

Brendan Connell

Adriana Díaz Enciso

Hayden Peters

Suzanne J. Willis

Kayleigh Marie Edwards

More details will be announced in due course.