Angela Slatter's Blog, page 15

October 6, 2020

Competitions, Crafting Through Critiquing, and the Short Story: Some Notes

Art by Kathleen Jennings

This is another redux article ( I wrote the original version for The Australian Writer’s Marketplace back in the mists of time).

Competitions, Crafting Through Critiquing, and the Short Story

I’m often asked how to win short story writing competitions: weird, right? If I knew that, I’d have won one by now. Competitions are uncertain ventures at the best of times, but if you haven’t put the effort into crafting your story, then the chances of your work getting past the first hurdle are slim. Incorrect spelling, grammatical infelicities, plot holes, logic abysses, repetition of word, phrase or action, unconvincing descriptions and stereotypical characters are all the hallmarks of unpolished writing. They are also the hallmarks of the first or second draft, where you’re still figuring out the story for yourself. But by the third or fourth draft, the issues listed above should no longer be in evidence.

So, how do you improve? Well, with a lot of practice, some handy hints, and a critique group. Writing is absolutely a solitary pursuit – but critiquing (which can be the foundation stone of a good edit) needs more than one head. Misery loves company!

In this article I’m going to highlight the problems I see most frequently in short stories, offer some tips for the lonely nights of editing, and talk about what a good critique group should do.

In general

The short story is precisely that: short. It’s been called a ‘widened moment’ and that’s what the writer is examining, a moment, a slice of life. Back story is not given in great chunks of info-dump, but rather hinted at through dialogue and implication – the form requires a deft hand.

For me short stories are very much about identifying the most essential elements I want to show: what are the critical things I need to reveal about my characters, my setting, my dialogue, my plot? The short story doesn’t have the luxury of a long roll-out or a huge cast of characters – every component must be distilled to its absolute essence. Everything in a short story needs to work hard (but seem to be effortless), so you must be quite ruthless about what is left in and out. The magic is all smoke and mirrors, all sleight of hand.

One of the first things you do on your first read through of a finished first draft is establish if you have given the reader a lot of information about a character’s past, present or future that’s irrelevant to the story at hand. Similarly, are your descriptions lush and detailed, but not really needed for the tale you’re trying to tell? Have you given great swathes of background about an incident that has no bearing on this tale? The first draft is when the writer tells themself the story and works out foundation details, which are not actually things the reader needs to know –

if a piece of information is not critical, then remove it – otherwise you’re wasting words.

Spelling, grammar and punctuation

These three things are fundamental to communication – to getting your message across. Neither spelling nor grammar nor punctuation are simply suggestions you may or may not choose to follow. There is a world of difference between ‘there’, ‘their’ or ‘they’re’ – and if you as a writer don’t know what the difference is, then how is a reader supposed to divine your meaning? Punctuation denotes the rhythm of your prose, gives a reader the beats, shows them when to pause, indicates the passage of time. Correct usage is not negotiable.

Your greatest friends are the dictionary, the thesaurus and a grammar book such as The Little Green Grammar Book (Mark Tredinnick), Eats, Shoots & Leaves (Lynne Truss) for punctuation, and the good old staple Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style.

Characters

When re-reading your draft, think carefully about whether your characters are believable and well-rounded or cardboard cut-outs. A stereotype is a ‘personality shorthand’, and works very well in advertising and anecdotes, but in a short story you want a character to have depth, a layered personality. With that comes reader engagement and understanding; if a character is nuanced and believable, a reader will keep reading. Stereotypes are lazy writing – make your characters richer by reflecting the human condition through them. Show what your protagonists want, need, fear and you will hook your readers because they can relate to the struggle of another.

When it comes to setting descriptions, you needn’t list every item in a room, nor every tree in a field. You need only ensure that your story is not occurring a ‘white room’: what would the character see upon entering the room? What details will tell the reader the where and the when of the story? For example, is there a velvet fainting couch or a rocking chair or a metal barstool? A four-poster bed or bunks? Items that are going to be important to the story show be shown early on, so they are already ghosting – foreshadowed – in the reader’s mind. Surprise appearances of anything that solves all story problems at the end of a tale will strain credibility, and using deus ex machina phenomena to explain otherwise unsolvable plot problems will not win you any prizes.

Repetitions – considered and ill-considered

You should always be aware (and beware) of repetitions. Sometimes a particular word or phrase will pop up over and over, which means your writing is going to lack the layers that a healthy variety of language brings. A broad vocabulary adds texture.

Repetition used in a considered, intentional fashion to create a rhythm or emphasis, when done properly, works beautifully. It’s a device that generally functions best when the repetitions of the feature word are placed in close proximity – too loose a scattering tends to lose connection and therefore the intended rhythm. Another thing to check carefully is whether your characters are constantly bursting into tears, sighing, sitting in silence, scratching their heads, wringing their hands, clenching their fists, or holding things aloft. Your protagonist needs to have a range of actions and reactions. Unintended repetitions are wasted words.

Dialogue

Dialogue needs to sound like human speech, but it isn’t actually the same. When we talk, our conversations diverge and meander, filled with irrelevancies that don’t necessarily add anything to our store of knowledge or the conduct of our existence. There are a million words wasted in the every day, but written dialogue is another beast all together. It has to be or you risk boring (and losing) your reader.

Its purpose is to move the story, to give subtle insights into characters, set a mood, and to pass on required plot information. Dialogue must progress things subtly, obliquely, rather than in info-dump fashion where everything is revealed all at once.

Do you really need that last sentence?

Something I see a lot is the Unnecessary Last Sentence. If you’ve written a glowing paragraph describing a lovely location – showing the reader a paradise – then don’t write final telling sentences such as ‘It was beautiful’ (or even worse, ‘It was indescribable’). Do not tell the reader about something you’ve already shown.

The critique group

Apart from applying the above to your own work, you also need to apply it to the work of others – the members of your critique group. The hardest thing in the world is to assess your own writing. This is where a critique group can help with picking out repetitions, spelling mistakes, and finding plot holes you may have missed.

The point of the critique is to make your story the best it can be in and of itself. The group should be a forum where you learn to improve. A group with more than ten members is too large – too many voices, too many opinions. There should be folk with varying levels of experience – so the newer writers can be mentored. There should be regular meetings, and rules for conduct – such as a two minute time limit in which to deliver a critique, a solid silence rule for the person receiving the critique until the all critiques are done, respectful behaviour, and always remembering that the process is about the story, not the writer.

Where do you find a critique group/buddy? This can be tricky. Try writing groups via local libraries and writers’ centres. Doing short writing courses can help put you in contact with like-minded folk as well as teaching you how to critique properly. Don’t get me wrong: you won’t like everyone in your class and you won’t agree with them. However, there’s a good chance you’ll find one, two or three people you get along with and whose writing you like – people whose opinions you respect. That can become the core of your own critique group.

And in conclusion …

Finally, enter competitions by all means, but be reasonable. I cannot tell you the number of times I’ve heard people say ‘I can’t believe I didn’t win.’ Really?? Competitions are beyond your control: you don’t know who the judges are, you don’t know who the other entrants are, and you cannot know the standard of other entries. Judges’ opinions are entirely subjective, influenced by their own likes, dislikes and prejudices – all things over which you have no sway.

Enter with hope, but not expectation and remember that the only thing you can control is the quality of your own work.

To note: the above is aimed at the short story. If you’d like to learn how to apply similar ideas to your novel, there’s a nifty self-paced course I wrote for The Australian Writers’ Centre with the fabulous Pamela Freeman. It’s called Cut, Shape, Polish and there’s more info here.

October 5, 2020

Happy Anniversary to Me

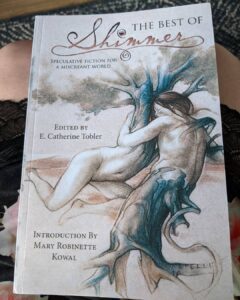

So I guess this arrival is timely as it reminds me that October is a sort of writing anniversary for me.

So I guess this arrival is timely as it reminds me that October is a sort of writing anniversary for me.

I’d moved back to Queensland after 4 years in Sydney, specifically to give writing a go as a serious career (read: eat 2-min noodles and live in a garret). I attended my first Brisbane Writers Festival just after, in Oct of 2003. Just before I set off on Day One (like literally 15 mins before I set foot out of the door), I received an email to say my flash fiction story “Hero of the Underworld” (I think that’s the title, it’s been a long time!) had been accepted by Antipodean SF. So I took it as a sign I was on the right path. Still here 16 years later, putting the finishing touches on my fourth novel, tenth collection, whateverth short story.

Still occasionally wondering if I made the right choice or if Fate is simply dropping breadcrumbs to lead me over a cliff at some point. But this is my happy place. Writing is the only thing that’s never made me feel unhappy at my core – it’s hard, yes, but it’s a joy.

But back to The Best of Shimmer – look at those names on the back.  Look at them. This wondrous little magazine gave so many of us our start – and look at the powerhouses they’ve become. Loooooook.

Look at them. This wondrous little magazine gave so many of us our start – and look at the powerhouses they’ve become. Loooooook.

Thank you, Shimmer (Beth Wodzinski, Mary Robinette Kowal, Lisa Mantchev, E. Catherine Tobler, Joy Marchand – I think I got all my first editors!), for giving me a run when I was a baby writer.

October 3, 2020

New Story Sale

Story Sale: I sold my first original fiction story to Nightmare Magazine. Thanks, Wendy Wagner! “The Wrong Girl” will appear in the December 2020 issue.

Story Sale: I sold my first original fiction story to Nightmare Magazine. Thanks, Wendy Wagner! “The Wrong Girl” will appear in the December 2020 issue.

September 29, 2020

On the Ancient and Secret Art of Formatting – Redux

Art by Kathleen Jennings

I wrote this post back in 2010 – remember 2010? When we could travel and didn’t feel the urge to torch-and-pitchfork anyone who coughed near us? Remember airports? Remember complaining about them? Remember how bad the coffee was and how expensive everything was and how surly the workers were? I miss airports so much.

What was my point?

Oh yes.

I am currently (as I apparently don’t have enough on my plate, am a glutton for punishment, and/or this is my equivalent of a hair shirt) reading slush for a friend’s publishing house. And I am seeing THE HORROR they deal with every damned day. So, I give you the key to the kingdom, people, once again. Reduxed with extra crispy rage bits.

The Secret:

There is a secret format that will help get you safely through slush piles, enchant your readers and make you the beloved of editors everywhere. It’s called ‘industry standard’ and it’s not hard to do. Some places still prefer paper over virtual, so paper-related instructions are also included.

Paper: use white A4 paper (A4 for Australia, letter for US, check your country of submission)

Spacing: double line spacing

Font: 12 point font in either Courier or Times New Roman

Print: black ink and only on one side

Margins: should be about 3cm all around

Header: put in Your Name/Title of the Work/Page Number

Secure: by means of bulldog clips or rubber bands – do not attempt to staple or otherwise bind your novel manuscript (short stories, not such a problem)

Send: copies only and not your original manuscript

Not every publisher/journal/magazine/editor will accept this, but the majority will.

How can you establish what individuals want?

Check their websites for submission guidelines. Do your research. Some, particularly online publications, will want things to be a little different: single-spaced in Arial Narrow, but most will accept the industry standard above.

These are not suggestions for you. They are rules to follow.

Why do I continue to harp on this? Firstly, because I am a grumpy old writer and secondly, while consistency may well be the hobgoblin of little minds, you need to remember that formatting is more than just a way of annoying people.

Formatting is signposting.

It says “This way to the story”.

The way words look on a page or a screen directs a reader’s attention. A paragraph indent says “Hi, new ideas here”. A section break says “Time has shifted. You can safely put your book down for the night if you wish.” Formatting indicates pauses, can affect pacing, it can make things easier or harder for someone to read/scan. It can invite a reader in or hold up a big red hand (or indeed, a big finger) to them that says STOP!

If you ignore the conventions and go with something that is single-spaced in Brush Script, in 9 point font, you’re creating the equivalent of contractual fine print. Just as fine print screams “I’m hiding something”, so does incorrect formatting – you’re hiding your story. You’re not encouraging someone to come in, to follow the tale.

And to an editor you’re saying “I don’t know what the rules are and I was too lazy/ignorant/stupid to bother to find out”, or “I am magnificent, special and precious – I will be a lot of work and rules don’t apply to me”.

And here is a big one: check out who the person is you’re sending a story and cover letter to. Are they a Dr, Miss, Ms, Mx, Mr, Professor, etc? What are their preferred pronouns? It’s not that hard to find out – check Twitter, a lot of people let you know there. Check out how they spell their name and be careful to copy that. And here’s the secret final step: make sure you get these things right. Don’t assume that the editor is male – few things cut short your chances of publication than an ill-placed “Dear Sir”. It doesn’t take you long to check these things out. To not do so is to say “I am a dipshit.”

Finally, formatting utilizes the hard-wired cues every reader has embedded in them. The familiar shapes have evolved over many, many years – why mess with them? For more information, you can go to Bill Shunn’s awesome site http://www.shunn.net/format/story.html.

September 27, 2020

Mentee Spotlight

At any one time, I have several mentees and I’m very proud of them all, but recently three of them have had some great stories published, so here’s a little spotlight. They’re all writing in different genres, so there’s a range to choose from. Enjoy!

A.A. Campbell just made her first fiction sale – to Overland, no less. She is a mother of two boys, a full-timer carer, a research assistant and a writer based in Brisbane. “Yoked” is a powerful and disturbing tale, which comes with trigger warnings.

A.A. Campbell just made her first fiction sale – to Overland, no less. She is a mother of two boys, a full-timer carer, a research assistant and a writer based in Brisbane. “Yoked” is a powerful and disturbing tale, which comes with trigger warnings.

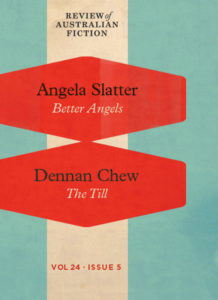

Dennan Chew’s first publication was “The Till” in the Review of Australian  Fiction, Volume 24, Issue 25 (2017). He’s an aspiring writer of dark comedy, crime and suburban gothic, and has variously been a copy writer, MMA fighter, and personal trainer. He has a Bachelor of Commerce, an MBA, and an MA in Creative Writing from Sydney University. Dennan is working on his debut novel, Plan B. His article, “Writing and Fighting”, appeared in the March-May 2019 issue of WQ Magazine. His latest publications are:

Fiction, Volume 24, Issue 25 (2017). He’s an aspiring writer of dark comedy, crime and suburban gothic, and has variously been a copy writer, MMA fighter, and personal trainer. He has a Bachelor of Commerce, an MBA, and an MA in Creative Writing from Sydney University. Dennan is working on his debut novel, Plan B. His article, “Writing and Fighting”, appeared in the March-May 2019 issue of WQ Magazine. His latest publications are:

“Mum” and “Waiting for Margot”.

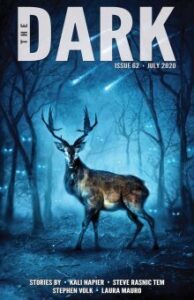

Kali Napier lives in Brisbane, Australia—on the unceded land of the Yuggera People. Her debut historical novel The Secrets at Ocean’s Edge was published in 2018 by Hachette Australia and Little, Brown Book Group. “Needles” was written with the financial assistance of the Queensland Government through Arts Queensland’s Individuals Fund for a short story writing mentorship with the incomparable Dr Angela Slatter. Kali can be found on social media Twitter:@KaliNapier and Instagram:@Kali.Napier.

Kali Napier lives in Brisbane, Australia—on the unceded land of the Yuggera People. Her debut historical novel The Secrets at Ocean’s Edge was published in 2018 by Hachette Australia and Little, Brown Book Group. “Needles” was written with the financial assistance of the Queensland Government through Arts Queensland’s Individuals Fund for a short story writing mentorship with the incomparable Dr Angela Slatter. Kali can be found on social media Twitter:@KaliNapier and Instagram:@Kali.Napier.

Read “Needles” here.

Winter Children: Paperback and ebook

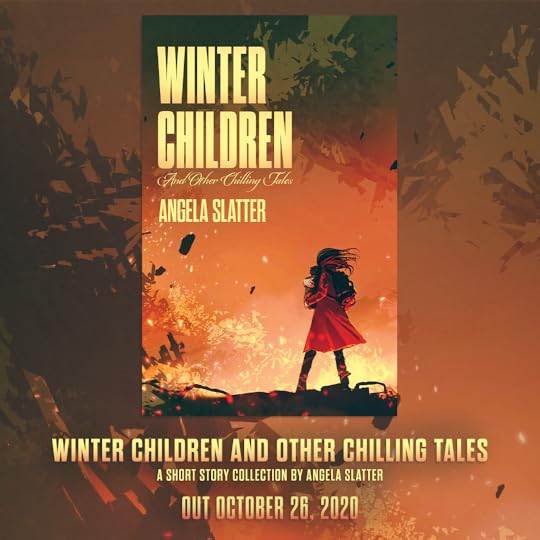

I’m very happy to announce that Winter Children and Other Chilling Tales – initially released as a 200 copy limited edition hardcover by the wonderful PS Publishing – is going to be a paperback and ebook from the equally wonderful Brain Jar Press.

I’m very happy to announce that Winter Children and Other Chilling Tales – initially released as a 200 copy limited edition hardcover by the wonderful PS Publishing – is going to be a paperback and ebook from the equally wonderful Brain Jar Press.

**ANGELA SLATTER PREORDER**

Mark your calendar’s, folks, because this Halloween we’ll be bringing Angela Slatter’s first horror collection, Winter Children and Other Chilling Tales, into print and ebook for the very first time.

First published as a limited edition hardback in 2016, this book quickly accumulated critical praise, got shortlisted for the Aurealis Award for Best Collection, and appeared on the 2017 Locus Recommended Reading list. It’s also a book that’s been very hard to track down if you missed the hardcover release.

Featuring eleven horror reprints and one new story, the book runs the gamut from very Australian vampire tales, uncanny Lovecraftian horror, and eerie folktales that Slatter’s readers have come to know and love (and, occasionally, have nightmares about).

You can preorder your copy from all good online retailers, your favourite bookstore, or direct from Brain Jar Press here.

September 21, 2020

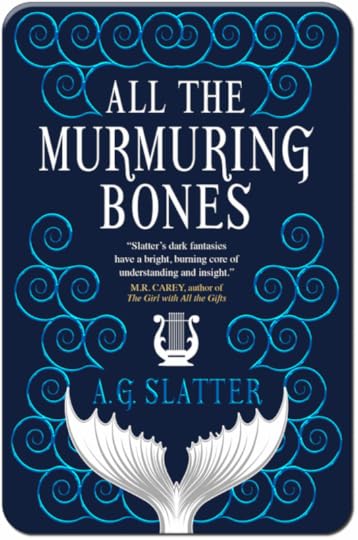

Cover Reveal: All the Murmuring Bones

I’m sooooooooo delighted to finally be able to show everyone the cover of my new novel! All the Murmuring Bones is set in the same world as the Sourdough and Bitterwood mosaic collections, and will be released into the wild on 9 March 2021 for the UK and US, and 4 May for Australian readers. Thanks so much to the lovely peeps at Titan for this wonderful cover! It will have foil … shiny, shiny foil.

I’m sooooooooo delighted to finally be able to show everyone the cover of my new novel! All the Murmuring Bones is set in the same world as the Sourdough and Bitterwood mosaic collections, and will be released into the wild on 9 March 2021 for the UK and US, and 4 May for Australian readers. Thanks so much to the lovely peeps at Titan for this wonderful cover! It will have foil … shiny, shiny foil.

Also, there’s an excerpt over at the Ginger Nuts of Horror reveal page. Here!

And here ’tis biggerer:

September 11, 2020

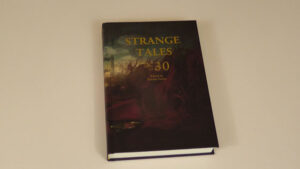

Tartarus Press at 30

I’m absolutely delighted to have a story in the new anthology, Strange Tales: Tartarus Press at 30!

I’m absolutely delighted to have a story in the new anthology, Strange Tales: Tartarus Press at 30!

The ToC:

Rebecca Lloyd, Mark Valentine, Andrew Michael Hurley, N.A. Sulway, Stephen Volk, Inna Effress, Ibrahim R. Ineke, Eric Stener Carlson, Jonathan Preece, Tom Heaton, J.M. Walsh, Angela Slatter, John Gaskin, D.P. Watt, Karen Heuler, John Linwood Grant, Reggie Oliver and Carly Holmes.

These eighteen entirely new stories have been brought together to celebrate the thirtieth year of Tartarus Press. Representing the best contemporary writing in the fields of the literary strange, supernatural, fantasy and horror, they range from the wry comic fantasy of Jonathan Preece’s ‘Great Dead American Authors Alive and Living in Cwmbran’, to the atmospheric horror of Andrew Michael Hurley’s ‘Hunger’.

In ‘Grassman’ by Rebecca Lloyd, two sisters come of age during a village ceremony, while in ‘Meiko’ by J.M. Walsh, a mysterious guest upsets the equilibrium of a country house party. Mark Valentine’s ‘Other Things’ documents the romance and strangeness of private lore, while the search for a missing girl leads to a sinister discovery in D.P. Watt’s ‘The Wardian Case’. Dark family secrets are gradually uncovered in Angela Slatter’s ‘The Three Burdens of Nest Wynne’.

Founded in 1990, Tartarus Press has become known for championing both classic and contemporary writers. The stories in this volume sit proudly within that tradition.

You can pre-order here.

September 1, 2020

Cut, Shape, Polish – New AWC Course

So, the editing course I wrote for the Australian Writers’ Centre is now live – on sale until 6 Sept 2020.

So, the editing course I wrote for the Australian Writers’ Centre is now live – on sale until 6 Sept 2020.

It’s self-directed (does what it says on the can), so you can start at any time and you’ve got twelve (12) months access to the online course – you just don’t get the mentoring experience. BUT you do get some of the more useful contents of my brain, along with additional Very Useful Stuff from the marvellous Pamela Freeman. It’s a really good place to start your manuscript polishing journey.

Ze blurb:

Your editing framework for a masterful manuscript

This online course is ideal for: People who have finished (or nearly finished) a draft of their manuscript.

You will:

Gain editing skills that will improve your story

Understand what you need to cut – and add – to your story

Know which characters need fleshing out

Easily identify plot holes and structural issues

Polish your manuscript into a publishable piece of work

Go here to enrol.

August 24, 2020

Shadow in the Empire of Light: Jane Routley

Photo by Trudi Canavan

What do readers need to know about you?

I’m a Melbourne novelist though I spent 7 years living in Denmark which turned me into a rampant democratic socialist. I love prose that’s light and rich and rollicking. I have two Aurealis awards for Best Australian Fantasy novel. I find short form works really hard to write so I admire people who write short stories. I love creating interesting characters as much as I like world building.

What was the inspiration for Shadow in the Empire of Light?

Georgette Heyer’s regency books really. I wanted to put a family of eccentric characters together and see how they muddled through. But I didn’t want to set it in regency romance land because that’s so tediously limiting to the female characters – all those double standards, all that need to guard reputation, all that lack of independence. So I created a world with none of these problems – wiped out a huge number of plot drivers doing it too, which was a nuisance. But if you’re not fighting sexism, you still have classism and racisim to fight. People do create worlds in which woman are equal without being exceptional, but in fantasy they don’t do it nearly often enough.

When did you first know you wanted to be a writer?

Since I could read. I still remember waiting on the school library steps at 5 thinking I want another book and I want to live in a story. Stories have been important to me ever since. I actually think that’s how I how I see people. As walking stories waiting to be told.

Do you remember the first story you ever wrote?

Not really, but I do remember one I wrote in primary school called “The Magic Telephone Box”. It took off into the air when people vandalised it. I liked a strong moral message in those days. The teacher told me I should be a writer. But I was always taking my dolls for jungle adventures in the long grass so it probably started much earlier.

Who are your main literary influences?

Who are your main literary influences?

Jane Austen, Angela Carter, Georgette Heyer and P.G. Wodehouse. I love good unself-conscious prose and strong storytelling. I’ve just discovered Frances Hardinge and am looking forward to devouring all her books.

Which five books would you take to a Desert Island with you?

I always find this question hard as I always want a new story and I love so many different books. The Collected Works of Shakespeare always has something fresh to offer and you can always enjoy rolling the delicious words over in your mind. Angela Carter’s Book of Fairy Tales for the same reason. A book about the plants of the Desert Island. A book of bushcraft for Desert Islands. A good solid poetry collection of some kind. Because if you love words, poetry is great but mostly you don’t have the time to take it in properly.

Who’s your favourite villain?

My favourite at the moment is Penguin from the TV series Gotham. Such a sociopath but so elegant too. Always unintentionally comical yet he has strong motivations and some sad back story. Gotham is full of outrageous characters, that’s the fun of it. It knows it’s from a comic book and works it.

What’s next for Jane Routley?

The ebook and the audio book of Shadow in the Empire of Light came out in early August and I’m working hard on book two. I’m hoping the hard copy of the book will be coming out in January 2021 and that we will all be out of Quarantine then so I can have a book launch at my favourite local pub. (Drop me a line if you want an invite) I’m also working at trying to learn how to do short stories better so I’m reading more at the moment. But it’s a tough gig.

Bio:

Fantasy and Science Fiction writer Jane Routley’s 7th book “Shadow in the Empire of Light” is due out now in epub and audiobook. She has published 6 books, 5 as herself and one as Rebecca Locksley, and won two Aurealis Awards for Best Fantasy Novel for the novels Fire Angels and Aramaya respectively. Her short stories have been widely anthologized and read on the ABC.

Jane was a judge for the recent Australian Role Playing Industry Awards. She has had a variety of careers, including fruit picker and occult librarian and she lived in Germany and Denmark for a decade. Now she works on the railways in Melbourne and is a keen climate activist.