Angela Slatter's Blog, page 16

August 23, 2020

Top Ten Tips for Curing Writer’s Block 2020 Redux

Art by Kathleen Jennings

We’ve all been there, had those moments when even cleaning the toilet seems better than writing. Some days the words are not interested in you at all and you reciprocate in kind. However, you’ve got to finish this piece for the sake of your sanity/self-esteem/bill-paying/deadlines/professional reputation. Writer’s block is a condition some folk don’t believe in, but which unfortunately and most definitely believes in you.

Myself, I think it’s just fear.

Fear of the words not being good enough, fear of what everyone else will say, fear of someone reading what you’ve produced and shouting “Emperor’s new clothes!!!” Fear of writing something that is a brown best described as “fecal” and thoroughly unsalvageable.

The hard fact of the matter is that you need to overcome this feeling if you’re going to be a professional. So, here’s my range of techniques for defeating writer’s block ? a range, because every writer, just like every snowflake, is different … and even more delicate.

Turn off the computer. Go and sit in another room. Revert to paper and pen. Jot notes. Sometimes re-establishing the connection between brain and hand and pen can work wonders ? and you don’t have the twin temptations of the backspace and delete keys.

Find your favourite book, open a page at random and re-type it. When you get to the bottom of said page, keep going ? but write your own story. Obviously you won’t be able to publish that, but you’ll find that the typing is like working with clay: you’re getting a feel for the words, the rhythm of the sentences, and while you’re re-typing someone else’s tale you’re not responsible for it. Not responsible for the quality of the work or the technical aspects of it, no one will see it and judge it, but you can learn by doing – and maybe unlock or unblock your own story.

Try a brief new project. I’m not advocating becoming one of those folk with four thousand new projects ? because the new beckoning project is always sexier than the old project demanding to be finished – but if you can give your creative brain a break from being banged against the wall of the thing that doesn’t want to work, it can sometimes help. Don’t start something huge; try a 500-word micro-fiction. That’s your entire story space; if you go over that 500 words, then you must edit it down (which is also good practice for your editing skills).

Again, step away from the computer. Don’t just step away, but turn it off. Go into another room otherwise you’ll feel it’s sitting there, mocking you. Pick up a book, find a comfy chair, pour the beverage of your choice, then read. An old favourite or something new. Anything but your current work. Or substitute “book” with “movie” (good or bad).

Leave the house. Go for a walk. Around the park, down the street. Make it longer than five minutes (and make sure you’ve got a small notebook and pen with you, or your phone with a note-taking app, just in case inspiration strikes) and just walk. You can think about the story more freely when you’re not in a Stockholm Syndrome situation with your computer. Or, even don’t actively think about the story; sometimes it will just work on itself in the back of your brain and present you with a surprise solution to whatever’s been bothering you. Not always, but sometimes; it works for me.

Write a foundation document for your story world – culture, characters, how long a period does the action of the story cover, setting, personal histories of your characters. As with anything, put a time limit on it or you will get lost in a time sink. I only suggest this, not as a procrastination technique, but as a way of getting to know your story better. You’ll realise pretty quickly if you’re writing a tale in which you don’t know how the magic/relationships/technology works, that you’re just applying “handwavium” to everything as a solution to plot problems. Then you’ll know where to start fixing things.

Write a haiku (3 lines: 5 syllables, 7 syllables, 5 syllables). Why? Because I like torturing you. No, not really. Well, yes really, but the point is to make you focus, think about words and meaning and how to pack as much as possible into a small space. Choosing the right word, rather than a series of almost-right ones.

Walk around the park with a voice recorder and talk to yourself about your tale; sometimes hearing it aloud will show you where the potholes are and, conversely, the hidden paths through the story forest. You might realise you’re using the wrong narrator, wrong tense, wrong point of view, wrong setting. Sometimes you just need to hear it. I do this at the local park, arms waving, talking to myself, nodding, shaking my head, occasionally shouting “Oh, of course!” and generally terrifying the other park-goers (bonus!).

Turn off the internal critic and just write; write utter rubbish and keep writing – because to paraphrase Kevin J. Anderson, you can edit crap but you can’t edit nothing! Yes, this one is the “Have a teaspoon of cement in a glass of water and harden up” option.

Read something you normally wouldn’t read. Choose something outside of your preferred genre because you just never know: you might find a new technique in someone else’s work that will help you get over the hurdles in your own. Read with an open mind, don’t spend your time thinking “OMG, I hate science fiction/literary fiction/romance fiction/epic fantasy”; just read.

So, give you inner critic some whiskey and chocolate and send them off to sit in a corner. Mostly the above advice is about taking a break from the project, but as with anything, set a time limit so that a one day break doesn’t become a one month, one year, one decade break. Conversely, don’t sit there watching the clock while you’re supposed to be taking a break. Set an alarm. Forget the alarm, it will go off when it needs to. Let it go. The words will come if you stop following them, stalking them, telling them you’re really nice and they should go out with you. No stalking. Not just a good rule for writing, but also for life.

And remember: writer’s block isn’t an incurable disease, it’s just a fear.

August 4, 2020

Red New Day & Other Microfictions

So this happened.

So this happened.

I’ve got a new collection of microfictions out today from Brain Jar Press.

Now, if you have queries about availability, etc, please direct them to the publisher, Brain Jar Press – coz I will just tell you to do that anyway. All good?

Oh! And also the cover art is by Thailand-based artist named Tithi Luadthong. Amazing work.

RED NEW DAY & OTHER MICROFICTIONS is a chapbook collection of 16 vignettes and microfictions. Preorder your copy at your favourite bookstore, or order direct from Brain Jar Press and get $4.99 off the print book price.

Red New Day & Other Microfictions (PREORDER)

Chapbook, Ebook

Out 7 September 2020

Mechanised monkeys, betrayed brides, irritable gorgons, harpists playing instruments of bone, acts of vengeance, and furies eager to feast.

Red New Day and Other Microfictions is a collection of vignettes from World Fantasy Award winner Angela Slatter, collected together for the very first time. Known as one of Australia’s finest authors of dark fantasy and sinister horror, Slatter’s myth-inspired morsels and terrifying short tales will remind you of the uncanny, wild, and beautiful things that can be found in small packages.

Paperback • 48 pp • ISBN 978-0-9808274-0-8

$3.63 – $9.08

Preorder here.

August 2, 2020

The Norma 2020

I’m absolutely delighted to have a story on the Norma shortlist for 2020! The Norma K. Hemming Award, which is designed to recognise excellence in the exploration of themes of race, gender, sexuality, class or disability in a published speculative fiction work.

I’m absolutely delighted to have a story on the Norma shortlist for 2020! The Norma K. Hemming Award, which is designed to recognise excellence in the exploration of themes of race, gender, sexuality, class or disability in a published speculative fiction work.

And I’m absolutely honoured to share this list with these amazing authors:

The finalists for the Short Fiction (stories up to 17,500 words) are:

“Like Ripples on a Blank Shore”, J S Breukelaar (Collision: Stories, Meerkat Press)

“The Mark”, Grace Chan (Verge 2019: Uncanny, Monash University Publishing)

“‘Scapes Made Diamond”, Shauna O’Meara (Interzone 280)

“The Promise of Saints”, Angela Slatter (A Miscellany of Death, Egaeus Press)

Winter’s Tale, Nike Sulway & Shauna O’Meara (Twelfth Planet Press)

“Rats”, Marlee Jane Ward (Kindred: 12 Queer #LoveOZYA Stories, Walker Books Australia)

The finalists for the Long Work category are:

Collision: Stories, J S Breukelaar (Meerkat Press)

From Here On, Monsters, Elizabeth Bryer (Pan Macmillan Australia)

The Old Lie, Claire G Coleman (Hachette Australia)

Blackbirds Sing, Aiki Flinthart (CAT Press)

Ghost Bird, Lisa Fuller (University of Queensland Press)

Darkdawn, Jay Kristoff (HarperCollins Publishers)

The Trespassers, Meg Mundell (University of Queensland Press)

July 13, 2020

The Attic Tragedy: J. Ashley-Smith

1. What do new readers need to know about J. Ashley-Smith?

1. What do new readers need to know about J. Ashley-Smith?I’m a British–Australian writer of dark – often speculative – fiction.

I’m not in any way nationalistic or even particularly patriotic, either to my new or my old home country (fingers crossed that ASIO/MI5 aren’t reading this interview). Still, I always seem to lead my answer to that question with where I’ve come from and where I am now – perhaps because it gives some insight into my status as outsider, wherever I find myself. Even though I’ve lived in Australia for approaching 15 years, I still feel out of place, as though I stepped through a portal into some weird parallel universe. Now, even Old Blighty, when viewed through this lens, seems unrecognisable and unfamiliar.

That kind of wrongness and disorientation, the sense of everyday things just out of true, is something that obsesses me. Another obsession is that inner dark from which the fantastic, the terrifying, and the impossible are born. The collision between the complexities of the modern day-to-day and the invisible or imagined world is another fixation, which I continually explore in my stories.

2. What was the inspiration for The Attic Tragedy?

The Attic Tragedy was born from three separate, inanimate ideas that rattled around inside me for two or three years before striking together and sparking a story. The first was the setting, the second was a dream, and the third was a rather cheap pun stolen from Nietzsche’s first book: The Birth of Tragedy.

Antique shops and attics hold a strange fascination for me – as I’m sure they do for many people. They are mysterious places, full of forgotten things, like storehouses for the discorporate memories of every object’s past owners. As a child I was obsessed with attics, my parents’ attic in particular, and always wanted to go up there to rummage around, certain I was going to discover some lost thing destined to lead me on a fantastic adventure (reading between the lines, you may be able to tell that I was a lonely, imaginative sort of boy). The Blue Mountains, where the story is set, is full of antique shops. We had just moved from the mountains when I started the story, so perhaps that was what triggered it.

I won’t go into the details of the dream – other people’s dreams are incredibly tedious, no matter how surreal or revelatory they were for the dreamer. This particular dream involved a girl who could speak with ghosts. She was going to a ‘specialist’ – a sort of medical exorcist – for an operation to cut off her connection to the spirit world.

Finally, the pun. I was reading The Birth of Tragedy as research for a novella I was writing at the time (Ariadne, I Love You, coming out from Meerkat Press next year). Throughout, Nietzsche refers to ‘Attic tragedy’, meaning Greek tragedy, but I loved the images that came to mind when I muddled the meaning and the title sort of stuck.

Of course, none of these elements on their own is much of a story. And even put together they were only a half-living thing. It was the character of George, who emerged in the process of writing, that really brought the story to life for me and made it the thing it is now.

3. When did you first know you wanted to be a writer?

I first started imagining myself as a writer around the age of ten or eleven. At that time, I hadn’t really made the connection between being a writer and actually writing.

I was a next-level daydreamer throughout my childhood (and, frankly, to this day), and a vivid night-dreamer. My head was always full of stories. Mostly, though, it was just wool gathering. I did write a few actual stories at that age, but I didn’t start identifying as a writer who writes until I was on my way to university. By then I was a card-carrying, chin-stroking, wannabe beatnik, hiding out in the corners of cafes hoping I looked deep. Scribbling mind-rubbish onto a legal pad, then, was de rigueur.

I didn’t learn to actually finish stories until about six years ago. That was around the same time the stories I wrote started getting published. (Doubtless a coincidence.)

4. Can you remember the first story you ever wrote?

Back when I was about ten or eleven, I had a hideout in what we called “the cellar,” which was really the foundations of our house. Underneath the downstairs floorboards an alternate version of the house was carved. A cramped space, with a floor of concrete dust and brick shards, somewhere between two and three feet from the ground to the floorboards. It was entirely dark and mimicked the layout of the rooms above, with crawl-spaces knocked into the brick walls. I had a camping mattress and some blankets down there, and used to lie about reading 80s Stephen King novels: Carrie, The Stand, Salem’s Lot.

I’m going in to all this (what some might argue is extraneous) detail, because the description of this den, the memory of it – close and dank, faintly redolent of mildew – is so intertwined with the first story I remember writing. I wrote it in a hardback A4 journal with a buff cover, the inside pages closely lined. The story itself was little more than a few paragraphs, and took up only about a third of one page, but it was extremely gory. It was about a woman who threw salt over her shoulder, so enraging the Devil that he dragged her straight to Hell and horribly disembowelled her. There wasn’t much in the way of a narrative arc. It was, however, VERY descriptive.

Not long after that, I heard what I thought was a body dragging itself across the rubble in the next ‘room’ of the under-house. I fled the den with my heart in my throat and have not been down there since.

5. Who are your main literary influences?

The answer to this question would be different depending on when you asked it. My influences have shifted over time and new inspirations emerge whenever I’m immersed in a project, trying to find a particular tone or approach. Rather than swamp you with my life story in literary heroes, I’ll go with the two most prominent and consistent for me recently, going back about the last five years or so.

The first is – perhaps predictably – Shirley Jackson. I came very late to her work, but fell into it like a lover’s embrace. The first book of hers that I read was The Haunting of Hill House and, reading it, I felt I had come home – not to Hill House, of course, but to Jackson’s way of viewing the world, and particularly the supernatural. In all of her stories that I have read, what’s in the foreground is the people, all their psychological complexities painted with such a deft and subtle brush. The weirdness is everywhere, but it’s in the background, found only in the gestalt and not in any one or other element. The supernatural is ever present, but always uncertain. Throughout Hill House, the reader is never entirely sure whether the haunting is ‘real’ in any measurable sense – it is both real and, at the same time, only in the minds of those who perceive it. And the characters through all of her books and stories are just wonderfully unusual, wonderfully real: Eleanor and Theo; Merricat and Constance Blackwood, Uncle Julian; Eleanor, from my favourite of her short stories, The Intoxicated. I could go on, but will have to rein myself in, before I start to rave sycophantically…

The other author currently in the ‘Where have you been all my life?’ category is Patricia Highsmith. I was struggling to make sense of a novel I have been drafting and redrafting for several years, trying to understand what in the hell sort of book it even was. Reading Strangers on a Train blew me away, and made me see immediately what I was supposed to be trying to achieve with my own book – and all the ways in which I was nowhere near achieving it. The fact that Highsmith wrote Strangers in her late twenties never ceases to nauseate me. And that she then followed it up with so many unique and extraordinary classics: The Blunderer; Deep Water; This Sweet Sickness; and, of course, the books for which she is most famous, the five novels covering the life of Tom Ripley, affectionately known as ‘The Ripliad’. No author has held so transparent a lens to the horrors of suburban psychopathy, or portrayed the crimes of the everyday with such clarity and brutality. Finding Patricia Highsmith was, for me, like tripping down a bottomless well. Her work is so bleak, so searingly perceptive, and she is so damn prolific – it’s a deep well.

6. You get to take five books when you are exiled to a desert island: which ones are they?

I’ve thought about this one long and hard. If I was truly exiled, there are very few books that would bear a lifetime’s repeat reading. I’ve gone here for a mix of practicality and longevity – by which I mean, I’ve probably taken this question way too seriously!

The SAS Survival Handbook

Field Guide of Tropical Reef Fish

Complete Poems of Walt Whitman

The Odyssey (Ancient Greek version)

Ancient Greek to English dictionary

Books 4 and 5 could just as easily be: Crime & Punishment, and a Russian/English dictionary; or Journey to the West, and a Mandarin/English dictionary; or [insert very long book written in a language not my own, plus the means to slowly translate said book over many, many years].

I hope I’d be left some pens and paper, too. Or would I have to get handy with seagull quills, squid ink and dried palm leaves?

7. Who’s your favourite villain in fiction?

As a rule, I tend to be more interested in stories where the characters possess a certain moral ambiguity, rather than the cut and dry hero vs villain type of narratives. I like not being able to rely on characters to do what I want them to do – or for them to be doomed always to do the things they shouldn’t.

Having said that, there are certain antagonists who scare the willies off me. I was watching the new series of Dark recently, which has three villains who are particularly creepy. I’m not going to talk about them – this isn’t a question about TV – so no need to worry about spoilers. Rather, they are a jumping-off point for a particular kind of psychopath in fiction that I find most terrifying – they are embodiments of some archetypal darkness or violence, precisely because their motives are incomprehensible and somehow outside of reason.

In Cormac McCarthy’s novel, The Outer Dark, there is a trio of ‘bad men’ who seem to embody the horror that lurks just beyond that borderline between civilisation and the seething chaos beneath. I get similarly freaked by the character Pozzo, in Beckett’s Waiting For Godot, who enters the play like some monstrosity from The Road, with his slave jester in tow.

And don’t get me started on …

8. Person you would most like to collaborate with?

I expect I’d be a terrible collaborator. One of the things that drew me to writing – after studying and making films at uni, followed by a decade or more in bands – was the degree to which I could have control over everything. I’m still coming to terms with my own way of doing things, so can’t imagine getting back into that collaborative mindset with this, my last bastion of creative control.

Having said that, I’m not opposed to it. But I can’t think of anyone off the top of my head.

9. What’s next for J. Ashley-Smith?

Did I mention I have another novella coming out from Meerkat Press in 2021? And there’s a short or two coming out this year, including a novelette, The Black Massive, about teenage ravers who fall in with an eldritch crowd. That’s coming out in October, in the final (sobs) issue of Dimension6.

I’m also on the home stretch of a suburban suspense novel I’ve been writing on and off for the last few years – imagine if Patricia Highsmith had written Lord of the Flies. It’s set on an Australian beach holiday and is about an eleven-year-old sociopath coming into her full power. I hope to have it wrapped by the end of the year – but I’ve been saying that every year since 2016, so…

Bio:

Ashley Smith is a British–Australian writer of dark fiction and other materials. His short stories have twice won national competitions and been shortlisted six times for Aurealis Awards, winning both Best Horror (Old Growth, 2017) and Best Fantasy (The Further Shore, 2018). His debut novelette, The Attic Tragedy, is out now from Meerkat Press. He lives with his wife and two sons in the suburbs of North Canberra, gathering moth dust, tormented by the desolation of telegraph wires.

You can connect with J. at spooktapes.net, or on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

July 2, 2020

How Long Does Stuff Take?

Art by Kathleen Jennings

And by “stuff” I mean a career as a writer.

To start off, remember this: it’s unlikely that the first thing you write – be it short story or novel or article – will be the first thing you publish. I can only talk about my own journey with any authority, so that’s what appears below. Also keep in mind: while you can study another writer’s career and learn from it, you can’t actually replicate it because (a) you’re not a Replicator, and (b) the conditions and influences that occurred during their journey aren’t going to be the same prevailing winds as when you’re writing.

I spent many years scribbling and not sending.

I then spent years scribbling and sending and getting rejections. I used all those rejections (sole-destroying as some were) as fuel, to either learn to write better or – and this one is important – to learn to ignore some opinions. If they weren’t helpful, if they didn’t make me learn about writing in a positive way, then I learned to ignore them. What they did teach me was that there are people in the writing and publishing community who are assholes, for a whole variety of reasons, but they are assholes nonetheless. I learned (a) not to be like them, and (b) to not engage with them – they’ve got their own issues that I can’t do anything about and don’t want to buy into. So, they are not on my radar – time spent worrying about their opinions is time I have wasted that I could have been using to write.

Then I spent a lot of years scribbling and sending and getting acceptances. And all the time in between I have spent improving my craft. Or trying to at least.

A lot of people seem to think I’ve been incredibly productive in a short space of time. I’m pretty productive, yes, but I’ve been doing this for almost 15 years now with intent. So, here’s a brief timeline to give an idea of how long the “with intent” part of my career has taken. This is my version of “How long does stuff take?”

2006: I had my first 2 stories accepted (1 by Shimmer and 1 by Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet). I also published 3 other stories. So, a total of 5 stories.

2007: I published 4 stories.

2008: I published 8 stories.

2009: I published 6 stories.

2010: I published 4 new stories (2 co-written with Lisa L. Hannett), 2 collections (one mostly new stories, the other mostly reprints), and 2 reprints.

2011: I published 3 new stories, and 2 reprints.

2012: I published 3 new stories (2 co-written with Lisa L. Hannett), 1 collection (co-written with Lisa L. Hannett), and 3 reprints.

2013: I published 7 new stories and (1 co-written with Lisa L. Hannett), and 7 reprints.

2014: I published 9 new stories, 3 collections (1 co-written with Lisa L. Hannett; 1 entirely new, 1 mostly new stories, 1 all reprints), and 5 reprints.

2015: I published 5 new stories, 1 novella and 11 reprints.

2016: I published 7 new stories, 2 collections (both mostly reprints), 1 novel and 3 reprints.

2017: I published 9 new stories, 1 novel and 9 reprints.

2018: I published 5 new stories, 1 novel, and 10 reprints.

2019: I published 5 new stories and 7 reprints.

2020: I published 5 new stories, 1 collection (mostly reprints) and with any luck another collection (mostly new fiction), and 3 reprints.

2021: I will publish one novel (All the Murmuring Bones), and maybe a collection of short stories (by mid-2021 there will be enough reprints for another collection and I’ll write two or three new shorts to go with that), and there will be 1 reprint story that I know of.

2022: If the world doesn’t end, I will publish 1 novel, Morwood.

So, you can see how many of those collections are mostly reprints – stories pulled together from several years before to sit with other newer ones and freshly written ones. Hopefully they all fit nicely.

In there are also some award nominations and some wins (two of those for works co-written with Lisa L. Hannett).

There are definitely more nominations than wins. Now, if I never win another award, I am perfectly okay with that because what I got from these awards (apart from the joy of some very nice trophies and the buzz of accepting awards whilst wearing no shoes) was attention from publishers and readers overseas. I was able to expand my reading audience, and it led to new publishing contracts and a bunch of translations (into Bulgarian, Chinese, Russian, Italian, Spanish, Japanese, Polish, French and Romanian).

2017 Australian Shadows Award for Best Novel

2016 Aurealis Award for Best Collection

2015 Ditmar Award for Best Novella

2014 World Fantasy Award for Best Collections

2014 Aurealis Award for Best Collection

2014 Aurealis Award for Best Horror Short Story

2014 Aurealis Award for Best Fantasy Short Story

2012 British Fantasy Award for Best Short Story

2010 Aurealis Award for Best Collection

2010 Aurealis Award Best Fantasy Short Story

What you don’t see from these lists (but should be able to extrapolate) is the amount of work done over a very long period of time. Consistent writing and polishing and submitting. Researching markets, attending cons, networking either for myself or others. All. The. Time.

If I didn’t love writing so much, I’d call it grinding until I got my XP up. My point is that this career is cumulative. It doesn’t happen overnight.

You’re basically a duck: moving elegantly on the surface of a pond, while beneath you’re paddling like mad. Many’s the day when I’ve felt like a duck with its ballast incorrectly weighted, my head underwater, my feet in the air, very un-elegant and drowning. But I’ve kept going. I’ve learned from those further up the ladder, and I’ve done my best to help those lower down.

And I have kept moving.

And writing.

Because, in the end, everything adds up.

June 23, 2020

The Dead Girls Club: Damien Angelica Walters

1. What do new readers need to know about Damien Angelica Walters?

1. What do new readers need to know about Damien Angelica Walters?

She is the author of The Dead Girls Club, Cry Your Way Home, Sing Me Your Scars, and Paper Tigers, which is no longer in print, although I think there are copies to be found online here and there. She likes writing about women and monsters and monstrous things and sometimes likes to write stories that make readers cry.

2. What was the inspiration for The Dead Girls Club?

It started with the image of a woman sitting at her desk, receiving a half heart necklace in the mail. At that point I had no idea what had happened but I knew something between two friends had gone horribly wrong. In the horror genre, there aren’t nearly as many coming of age stories centered around girls as there are boys and while The Dead Girls Club is a horror/suspense hybrid instead of outright horror, I kept the novel’s focus on the girls in the story, the women they become, and their interactions and friendship.

3. Can you remember the first thing you read that made you want to become a storyteller?

When I was very small, my father used to take me to the library every Friday night and I’d emerge with a stack of books that I insisted on carrying. I’d have them all read by the end of the weekend, if not earlier and then reread my favorites until it was time to go back. My childhood is filled with the memory of books, and I still have many of mine from grade school on up, so I don’t think there was a giant leap into wanting to become a storyteller. Couple reading with a big imagination and it feels as though it may have been inevitable.

4. Can you remember the first story you ever wrote?

The first one I remember writing was when I was about eight. It was called “The Coughing Coffin,” written and illustrated in a stapled together construction paper book. I tried to sell it to my friends, but like most kids that age, they didn’t have any money. I’m not sure what it was about, but I can imagine and why I remember that title and none of the others I wrote around that age is beyond me.

5. Who are your main literary influences?

Margaret Atwood, Joyce Carol Oates, Shirley Jackson, Alice Hoffman, Agatha Christie, Sylvia Plath, Angela Carter, and I can’t forget Lois Duncan. Stephen King and Peter Straub have influenced me as well, but as time passes, I realize how much more of an impact the women I’ve read had on me.

6. What was the inspiration behind your novel Paper Tigers?

6. What was the inspiration behind your novel Paper Tigers?

Like The Dead Girls Club, it started with an image. (In all honesty, most of my work does.) I saw a heavily scarred young woman out walking late at night and coming across an old photo album in a junk shop window, a junk shop that happened to be open despite the late hour. I wanted to know where the woman got her scars, why she was so afraid at being seen, and what drew her to the photo album.

7. Who’s your favourite villain in fiction?

I’d say Gilead and the patriarchy in The Handmaid’s Tale. How can you possible fight against something that big and pervasive? And if you do, how can you hope to win?

8. You get to take five foods to a desert island with you – what are they?

Peanut butter, yogurt, peaches, apples, and cottage cheese.

9. Person you would most like to collaborate with?

Kristi DeMeester and I have written a story with Michael Wehunt and Richard Thomas (“Golden Sun” in Chiral Mad 4) but she and I have chatted about collaborating on one together. I’m sure it will be a grim, angry story with disturbing imagery. At least I hope so!

10. What’s next for Damien Angelica Walters?

I just finished the first draft of The Floating Girls: A Novel, the sequel to my 2014 Bram Stoker Award nominated short story “The Floating Girls: A Documentary” and now I’m working on the preliminary bits (outline, synopsis, characters sheets, etc.) of the next novel, tentatively titled Women of a Certain Age. Other than that, hopefully a story with Kristi and after all that, who knows.

Bio:

Damien Angelica Walters is the author of The Dead Girls Club, Cry Your Way Home, Paper Tigers, and Sing Me Your Scars. Her short fiction has been nominated twice for a Bram Stoker Award, reprinted in Best Horror of the Year, The Year’s Best Dark Fantasy & Horror, and The Year’s Best Weird Fiction, and published in various anthologies and magazines, including the Shirley Jackson Award Finalists Autumn Cthulhu and The Madness of Dr. Caligari, World Fantasy Award Finalist Cassilda’s Song, Nightmare Magazine, and Black Static. She lives in Maryland with her husband and a rescued pit bull named Ripley. Find her on Twitter @DamienAWalters or on her website at http://damienangelicawalters.com.

June 14, 2020

Claiming T-Mo: Eugen Bacon

What do new readers need to know about Eugen Bacon?

My writing is a curiosity, unconstrained by form or genre. I take on aspects of my characters, immerse myself into their worlds. The writing is a search, a coming through. It is also an invitation. Be at ease with my characters, with the places and languages I have shaped in ink.

What was the inspiration for Claiming T-Mo ?

The original name of the novel was Outbreeds, a breed of others. The black speculative fiction intends to engage with difference, with ‘otherness’, with being between worlds.

As I crafted it, I also explored one of my PhD research questions:

‘Can a writer of short fiction productively apply a model of stories-within-a-story to build a novel?’

I’m most comfortable as a writer of short stories. In Claiming T-Mo, I created purposeful adaptations, embedded vignettes, where the arrangement of stories, themes and collective protagonists hold the text together. The story flows smoothly from one point to another, each in part bearing a concealed self-sufficiency interlinked and layered into the composite. I wrote story by story, creating in a discipline already familiar.

How did you come into contact with Meerkat Press?

This is how I do: I read something and love it—I look to see who published it. When I was in the Andromeda Spaceways Magazine editorial team, we ran a review of Keith Rosson’s Smoke City. I thought… this publisher is worth checking out. She was.

When did you first know you wanted to be a writer?

My father was an eloquent writer. I still remember his letters, that beautiful scrawl. I’ve always been able to write from the core, to express, or find out, exactly how I feel. My lovers never had any doubts: passion or rage!

You’ve also got a PhD – do you find that you can use any of that experience in your creative writing?

The PhD soared my writing. I understood my voice, and my hunger. My commitment, and focus. I could look at a problem, or a curiosity, and interrogate it like it was life or death. I explored the nature of selfhood within myself and within my characters and understood to interlace my immersion equally between scholarly and creative work.

Who are your main literary influences?

I grew up on Enid Blyton, Margaret Ogola, Chinua Achebe, Camara Laye, Ng?g? wa Thiong’o. Along the way I discovered theorist and critical thinker Roland Barthes and his notion of play in the language of writing. Toni Morrison and her aptitude of seeing narrative as radical, as creating the writer at the very moment the work is being created. Kate Greville (The Secret River), Octavia Butler, J. R.R Tolkien, Peter Temple (Truth), Michael Ondaatje (Divisadero), Sapphire (Push), George R. R. Martin (have you read ‘The Lonely Songs of Laren Dorr’?)—all influential writers who offer me models to benchmark against.

What made you decide to write your non-fiction book, Writing Speculative Fiction ?

Writing Speculative Fiction was the exegetical part of my doctorate. As I shaped the thesis, abandoning the language of ‘academia’, I saw potential in a book that spoke to the reader, and encouraged writing as play. Many publishers rejected it, including Macmillan, but I reworked it, reshaped it, resubmitted it, and was astonished when Macmillan said, yes.

You’ve done a few collaborations, the latest is Speculate with Dominique Hecq – how did that come about and what’s your approach to creative collaboration?

You’ve done a few collaborations, the latest is Speculate with Dominique Hecq – how did that come about and what’s your approach to creative collaboration?Collaboration is trust and respect. My love affair with Dominique started when she supervised my creative writing PhD at Swinburne University. In our first meeting, she looked at me and said, ‘Write, or perish.’ In the course of my candidature I published over 30 creative-writing-as-research stories and peer-reviewed articles, and presented papers in 10 international conferences. Dominique was the mother, the sister, the lover, the friend who brought out the scholar and writer in me. It was inevitable we’d work together on a project.

What can you tell us about your chapbook, Her Bitch Dress , from Ginninderra Press?

Prose poetry is the naughty child that refuses to be tamed. I love poeticity in text, musicality in words. I’m part of a prose poetry group run by the University of Canberra, led by Prof Paul Hetherington—its members are scholars across the world.

We respond to each other at random in a form of dialogue, words that cartwheel on a trigger: a word, a metaphor, a feeling. We attach and detach from the world in a safe and playful space, where we trial language across genres in its forms, and use text to disrupt or find meaning. Here’s the piece that inspired the chapbook’s title:

Her bitch dress

That long weekend, the jazz singer and her snippet of song full of scatting. The band with its clarinet and a guitar and a piano, and the man with a crimson shirt and an ebony bowtie behind the double bass shaped like a rowboat. She commanded the audience, so young—she’s only twenty—really captured you, my love, when she sang in that dress, her flowing, strapless dress the colour of burnt orange, ‘I’m so lucky to have loved you.’ You clutched my hand at her croon and gave her your soul.

What’s next for Eugen Bacon?

I want to read more, to write more black people stories. I’ve finished black speculative vignettes on climate change—what happens when the water runs dry. Before that was a short story about a water runner, a futuristic fiction about the price of water.

Luna Press Publishing invited me to participate in an academia lunare project on worldbuilding in fantasy and science fiction. My contribution studies worldbuilding in Ng?g? wa Thiong’o’s The Perfect Nine: The Epic of G?k?y? and M?mbi – where he uses literary devices of worldbuilding through creation mythology, culture, nature and the otherworldly.

If all goes well, you’ll see new stories in upcoming anthologies. There’s also an afrofuturistic novel set in a socialist country.

Bio:

Eugen Bacon is African Australian, a computer scientist mentally re-engineered into creative writing. She is a board director of the Australian Society of Authors. Her work has won, been shortlisted, longlisted or commended in national and international awards, including the Bridport Prize, Copyright Agency Prize, Ron Hubbard’s Writers of the Future Award, Australian Shadows Awards and Nommo Award for Speculative Fiction by Africans. Publications: Claiming T-Mo, Meerkat Press. Writing Speculative Fiction, Macmillan. In 2020: Her Bitch Dress, Ginninderra Press; The Road to Woop Woop & Other Stories, Meerkat Press; Hadithi, Luna Press Publishing; Inside the Dreaming, NewCon Press.

June 1, 2020

What to Do When You Don’t Have a Book Coming Out

Or

Or

What to Expect When You’re Not Expecting

Being a writer may well mean writing all the time (in which case, you’re fortunate), or writing in as much of the day or night as you can steal from the world and your family and your day job. The point is that it’s difficult, a lot of effort goes in before anything ever sees the light of day. You’re unlikely to be constantly bringing out a new novel, or even a series of short stories. It can be a long time between drinks – some of which I’ve covered in this post right here.

This post today is about the stuff to do in between times: the useful busywork that will help you keep going. It will help lay the foundations for your next steps. Now, please keep in mind that the usefulness of this advice will vary depending on the point you’re at in your career, your degree of self-pity/self-righteousness, and your willingness to drag your butt out of the traditional writerly “nobody loves me, everybody hates me, think I’ll go eat worms” impostor syndrome pit.

There’s a myth that says once you’ve got your first book deal, you’re set. You’ll always have a book deal. That your first publisher will be your forever publisher and you’ll be faithful to one another until death do you part. Even then, your literary estate will live on and all those bits of dross you never wanted out in the world will somehow appear in published form as your ghost howls into the void. Wait, where was I going with this?

Oh yes. Your first publisher won’t always be your last publisher. You won’t necessarily have a novel out every year for the rest of your life. And you know what? This will probably bother you and make you feel bad at some point – or all points, but don’t reach for the whisk(e)y and revolver quite yet. There’s a good chance (unless you’re very well-adjusted – but hey, we’re talking about writers here) you will become convinced everyone is going to forget who you are; that you’re sliding to the bottom of the snake in life’s game of Snakes and Ladders.

You’re in between contracts: your publisher has decided they don’t want any more books from you and it’s hard not to take that personally. Your books haven’t sold as well as they’d wished; your editor has moved on and now you’re an orphan; the publishing house is changing direction; their marketing plan of “throwing shit against a wall and seeing what sticks” simply hasn’t worked to the surprise of no one but the marketing department. Not to mention that your agent has decided they shall slip away into the night leaving neither a forwarding address nor even a fiver on the dresser.

It’s easy to feel that your career is over.

It’s probably not.

There are things you can do:

Keep writing

Just keep writing. A writer writes, folks. Keep writing. Just coz you’re in a slump doesn’t mean you’ve failed. Get off the fainting couch and write. Or, if you insist on staying on the fainting couch, then at least grab a notebook and pen and/or the laptop and keep writing. Because this is the equivalent of stocking up your pantry, so that when someone comes asking for what you’ve got in your bottom drawer, lo and behold you will have perhaps 72 manuscripts ready and waiting. Write the next novel because that’s your job.

Reprints

Find second and third homes for your previously published short stories. Put in some time researching markets for reprint anthologies, and podcasts that are willing to turn wordery reprints into speakery. And don’t forget translation markets that are happy to have reprints for first time translations. See where other people are getting their work reprinted, podcasted and/or translated and see if you can find your way into those venues.

The bonus is that you’ll get paid again for something you’ve already been paid for – huzzah! The rate probably won’t be as high, but it’s still better than a poke in the eye with a sharp stick. And this can help keep your work circulating during the publishing droughts.

Short stories

If you’ve been writing novels, you could try something different and school yourself in the art of the short story – just like a novel only shorter, with fewer characters and probably a more ambiguous ending. Or something like that. That doesn’t mean it’s easy – it’s not, trust me – but it is a way of extending your writing skills and possibly finding new markets and new readership. And even if they don’t find a home, you’re building up the table of contents for a short story collection somewhere down the track.

Community

One of my personal bugbears are writers who disappear when they haven’t got a novel coming out: they only turn up in your feed when there’s a book on the way. This is short-sighted and looks very much like you simply can’t be bothered interacting unless you’ve got something to shill. That might not be your intention, however …

There’s a community out there of readers and fans who like your work. There’s also a community of fellow writers out there who probably understand a lot of what you’re going through: talk to them. There are new writers coming up through the ranks who look to those ahead of them for how to act: lead by example. (Hint: don’t be an asshole.)

Stay present in the community. I’m not suggesting that you spend all your time on the socials – coz you should be writing and you might be amazed at how a novel fails to materialise when you’re on Facebook – but spend a bit of time interacting with the people you want to read and support and promote your work when it’s coming out. Don’t just be that relative who only turns up on the doorstep wanting a handout at Christmas, or because your kid’s got Girl Guide cookies to sell (although those are admittedly delicious cookies).

Network

Go to conventions and festivals even if you’re not on panels and don’t have a book to promote. Meet people – yes, I know, we really only like people as an abstract concept on our computers where we can block or mute them, but sometimes you need to go out amongst the humans. You might make new friends, have interesting conversations, and form new networks that could be helpful later on to you or someone else in your circle. Or, you know, just enjoy being there and not being “on show”.

Go to other people’s launches, buy their books, be supportive. Do not, I repeat do NOT advertise on your website that you’ll be there. It’s not your event! It’s not about you. You’re not a special guest star unless you’re launching the book, and even then you’re just the MC.

If you’re in a position to mentor a new writer, then do so. You don’t have to give up your time for free (nor should you unless it’s your choice), but you can help and you can influence. You can help shape the future of literature and if that doesn’t appeal to your god complex, I don’t know what will. You can offer the benefit of your own experience.

Join a writers’ group – one that suits your needs and the amount of time you’re prepared to commit. It can be a safe space to talk out frustrations – writing might be a solitary pursuit, but writers still need some human contact. And your cat, whilst adorable, is probably an asshole (harsh critic), and your dog, also adorable, probably thinks you can do no wrong (rabid fan) – so they are not the best givers of feedback. Also, they can’t actually talk. Sorry.

And you know what? These sorts of interactions also give you the chance to learn. There’s no point in your career at which you will know everything. Really. I’ve said it before, and I’ll probably say it again: you can always learn something from someone, even if it’s that said person is a total butthead. But you learned that, right? Now you have the basis for a new character in a story.

Write Blog Posts

By which I don’t mean write anything that could be termed a “manifesto” (and therefore used at your trial), but rather useful posts that can help yourself and others with common experiences and reference points. If you’ve had an epiphany about your writing process, then write about that – someone else might find that info useful. So might you, at a later date, when you come back to it and think “Hey! That insurmountable problem I’m not surmounting now? I surmounted it before! That’s how I did it! Thanks, Past Me.”

Don’t Sulk

Ultimately, don’t skulk. Stay present.

I know it can sometimes feel difficult – and our natural urge towards imposter syndrome is just waiting for the moment to flare up like a nasty rash. The inner critic gets louder and louder.

“I’m irrelevant.”

“I have nothing to promote.”

“I have nothing coming out.”

But those thoughts lose sight of the fact that (a) you probably have had things published and you have already contributed to the literature of the world, and (b) you will probably do so again, if you’re not a self-pitying idiot and you continue writing and producing.

How do you keep doing that?

Simple: you do the things above – it’s part of the business of writing – and you write for yourself. First and foremost, you are your first audience. If you try to write a first draft of something with the weight of “this must be a bestseller” or “this must win awards”, then you are setting yourself up to fail. Write the story you want to write – in order to entertain yourself in the first instance, in order to get the words out of your head. In order to have fun. (OMG look at all those repetitions of “first”.)

Your career is unlikely to be a constant stream of hits, accolades, festival circuits – and that’s kind of good because if you’re constantly on-the-road, it’s hard to write and create. Some people do it, sure. Some people can do it from talent, habit, sheer bloody-minded discipline. I am mostly not one of those people – I’m not good at creating when I’m doing festival-y stuff, when I’m promoting things, because I need a break between tasks that use different parts of my brain. Make the most of the quiet times, because when success hits it doesn’t leave much quiet time. Not a complaint, merely an observation.

Don’t waste time envying another person’s achievements. What they’ve

Art by Kathleen Jennings

got, they worked hard for and their career is just on a different timeline to yours. The only thing you can control is how you react to things. You can either do stuff that is positive and affirming and will help set you up for the next stage (manuscripts in the bottom drawer), or you can throw yourself onto the fainting couch and howl ad infinitum and still be there when things are looking up (dust bunnies in the bottom drawer).

So, make a list – what are you going to do first?

May 20, 2020

On the Importance of Being Edited

Art by Kathleen Jennings

Approximately 142 years ago, I wrote this as a guest post over at the web-place of Mr Mark Barnes. It appears here now as it’s wandered home, somewhat drunk, and can’t really remember where it lives anymore. Any typos you might find are intentional … or are they?

On the Importance of Being Edited (and Editing)

There’s a particular kind of arrogance that can trip up a new writer (and sometimes even an experienced one) and it goes something like this, “I just wrote The End, so it’s all done.”

No.

The End, to paraphrase The Mummy’s Imhotep, is just the beginning.

Your first draft is just that: a draft. It needs tender loving care as well as brutal pruning to shape it into a piece that’s not only something someone wants to read, but also something that someone (i.e. an editor/publisher) wants to (a) put into print and (b) pay you for.

Editing is a form of auditing and before an experienced editor/publisher will look at your work you need to make sure what you’re sending to them is the best you can produce. You must go over your own work to make sure that you have actually written what you think you’ve written: are spelling and grammar all present and correct? Does the ending match the beginning? Is the story’s internal logic flawless? Do characters act in a manner consistent with their motivation and characterisation? Are those characters believable and engaging or merely cookie-cutter stereotypes that interest no one? Does the pacing work as it should or does the story have a flabby middle that needs tightening? Are your descriptions apposite and sharp, rather than simply a bruised purple mess? My expertise is in short stories, but most of what follows can ? and should ? be applied to longer works as well. I can’t cover everything here, but I’ll do my best.

The task of self-editing always seems huge, but just like eating an elephant it should be done one bite at a time. I always start with the small stuff because it’s relatively quick and easy and it gives me a sense of achievement that buoys me up to tackle the bigger issues – yes, being a writer is a constant system of sticks and carrots. The basics are always spelling, grammar and punctuation. When you’re reading over a draft, put on your critical thought hat: have you used the right word? Have you written ‘enervated’ when you mean ‘energised’ because they sound a bit alike? I have marked more student pieces with this kind of assured idiocy in them than I care to remember ? some crackers I cannot burn from my memory include: “She spent the day begatting a meal for her husband”, “This gave the movement the inertia it needed to move forward”, and my personal favourite, “She danced around on the stage with a feather Boer around her neck.”

Have you used the correct version of words that have different meanings and spellings but sound the same? Your, You’re, Yore? Their, They’re, There? Where, We’re, Wear, Were (as in the Old English version meaning ‘man’)? Flaw, Floor, Flore (Latin for flowers)? A good idea is to keep a list above your desk of words that you know are a problem for you; every time you’re reading a draft, check against the list, make sure you’ve got it right. With any luck, the repeated reminders will help embed the correct meanings in your brain. It’s easy to make a mistake in the first draft – that’s what the first draft is for, making mistakes, throwing the brain-vomit onto the page. What’s not forgivable is to leave those mistakes in there after the second or third draft.

Grammatical mistakes, such as disagreement between your plurals and singulars, most definitely need to be fixed. If you know grammar is not your strong point, then find a writing friend who is good at it and learn from them. Punctuation is also very important: the old saw about “Let’s eat grandma” versus “Let’s eat, Grandma” is a perfect illustration as to why punctuation matters. Also collect – and read! – books such as Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style or Mark Tredinnick’s The Little Green Grammar Book or Lynne Truss’s most excellent Eats, Shoots & Leaves. These reference books should sit beside your dictionary and thesaurus.

And for the love of all that’s holy or otherwise, learn how to use apostrophes. Here’s The Oatmeal to tell you how http://theoatmeal.com/comics/apostrophe.

Another problem to look out for is that of unintentional repetitions: you’ve described something as ‘dark’ eighteen times in the space of a page, or seven times in two paragraphs, not because you’re going for a considered repetition to build a rhythm or a motif, but because it was the only word you could think of in your rushed first draft. Remember: the thesaurus is your friend. A lot of unintentional repetition occurs in descriptions or actions, so look for them there first. Replace those repeated ‘darks’ with ‘ebony’, ‘cinereal’, ‘shadowy’, ‘murky’, ‘gunmetal’, ‘charcoal’ … carefully consider the subtle sense you want the word to convey. There’s whole range of alternatives that will add texture to your writing – but don’t go overboard and make a simple sentence read like either an anatomical text or a bad romance novel: “Her heart beat strongly” never, ever needs to be “Her blood-pumping organ palpitated indomitably.” Also to note: don’t just do a global replace of the offending word with a new one.

You also need to develop an awareness of your crutch words – those you fall back on automatically and don’t even think about. Are you a repeat offender with ‘seems’, ‘that’, ‘suddenly’, ‘slightly’, ‘appears’, ‘maybe’? Do they pepper your manuscript like buckshot? Once again, a reminder list above the desk can do wonders to keep these words from cluttering up your work.

Another thing to consider during the self-edit is the length of your sentences, especially if you’re a new writer with less experience in crafting prose. Here’s the thing about long sentences: the more words you jam in there, the more likely your reader will get to the end of the sentence and go “Huh? What was the start of that? I’ve been reading for about fifteen minutes and I forget what the point was.” The more words you put between your reader and the story, the more chance your tale has of failing, of losing the reader. There are some writers who are simply masters of the long sentence: Jeff VanderMeer is one of them, Angela Carter is another. They also know this secret: a long sentence set amongst a bunch of shorter, sharper ones will stand out. It will stand out like a jewel; it will make the reader pause, catch their breath, marvel at the craft displayed. Shorter sentences are great for simply transmitting information and action, as well as keeping the pace cracking along. Longer sentences can be where you make your reader think more deeply – but you do need to frame them carefully to best advantage.

This brings me to Five Dollar Words. Is your narrative crammed with multisyllabic words as a matter of course? Does your sentence look as though it ate a thesaurus? Is said sentence verging on purple, with the prose so ornate and extravagant that it draws attention in the way a lime green mankini does? For the record, that is Bad Attention. The Five Dollar Word is best deployed, like long sentences, in a garden of Five Cent Words. That way it will have more impact.

The idea of minimising purple prose leads to another important characteristic of the short story: brevity. There is an art to making short fiction short and making it work. Henry David Thoreau said “Not that the story need be long, but it will take a long while to make it short.” This may seem self-evident and you’re thinking, “Well, d’uh”, but I’ve critiqued and edited a LOT of work in which there were too many words for the amount of story contained therein. You don’t have the same luxury you’ve got with a novel, that of great long wandering descriptions: as with life, you don’t get a second chance to make a first impression, so do it right the first time. Your descriptions must be powerful but precise: if you’re describing a character, give us their outstanding feature/s, the thing/s the reader will remember (or needs to know in order to comprehend the tale). If you’re describing a setting, again, tell us what we need to know in order to understand the story, although brevity doesn’t mean a white room, i.e. no setting given. It means, as my old friend and mentor Jack Dann says, “What does the camera see?” So, if a television camera were to pan through your scene what would/should it pick up?

What must the reader see when they enter that scene? A shotgun on the mantlepiece? Show us – carefully and casually scattered amongst a few other red herring items – what is going to be essential to the story’s resolution. So, if the shotgun is going to be fired by the end of the story, then show it in the first act, remind us about it (subtly) in the second act, then fire that shotgun in the third. My point? When you’re editing/auditing ask yourself “Does my tale do this/work in this way?”

Another important thing to keep in mind is structure. I like a three act structure because it gives you a good guide for where to put which plot points. It’s especially useful for new writers to train them in the rhythms of a short story, so they become second nature. When you’re editing/auditing your work, ask: do all of the parts make up the whole in the way they need to? Is there too much/not enough set up/foreshadowing in Act One? Is there to much exposition/marking time in Act Two? Is Act Three simply too short or too long? Has the climax of the story occurred in a fashion that leaves the reader saying “Huh?” because the writer hasn’t given enough foreshadowing/hints/ breadcrumbs in the previous acts? So, once again, you need to read your draft with a critical gaze: forget that it’s your baby and you love it to distraction; actively look for its faults.

Consistency is also critical, not simply in the spelling of particular words, but in the meaning you give to them and the way you use them. For example, if in your story you’ve allocated a specific meaning of “magical and dangerous” to “weird” and that is a recurring meaning, then keep that word specifically for use in that context. Don’t suddenly use it for “a bit off”. Similarly, make sure a character’s appearance remains consistent – don’t change eye or hair colour unless you’ve also given a very good reason. A one-armed woman should not suddenly be shown using a tool or weapon that requires her to have grown back her other arm, because that says the writer forgot who their character is and the limits within which they must operate. In addition, you must show consistency in a character’s motivation and action – don’t suddenly have your protagonist acting against their grain unless you’ve given them (and shown the reader) why they are doing so.

Finally, when you’ve done all of the above, is it over? Can you send it out into the wide world for publication?

No.

You do another draft, a second, a third, a fourth until you can no longer see any problems.

Then can you send it off for publication?

No.

You give it to your writers group or your trusted beta readers and let them find problems with it.

Why? Because, let’s face it, we’re all certain we know what we’ve written, and the mind will trick us into seeing words that aren’t actually there. You’re likely to see the ghost words because you know the story so well, you’re used to it, it’s like a long-term partner: you’ve stopped looking properly at their face, you’re relying on your memory and you’ve become too lazy to look for something new. Your beta reader, however, as a person who did not write this thing that means so much to you, is not invested in it – they will see omissions and highlight them. This is an essential part of the critique process, for which you must thicken your skin. You must not be so in love with your story that anyone pointing out its faults causes you to burst into tears/flames/defensive protestations about what you really meant/how no one understands your genius. The whole point of editing is to make your story the best it can be. Isn’t it better for a beta reader to find these problems rather than the editor/publisher to whom you’re hoping to sell it?

The other side of the critiquing coin is that being a beta reader for other writers will help you become a better self-editor/auditor. The more you’re exposed to the process, the more you’ll learn, the more able you’ll be to spot issues, and the more all these techniques will become second nature to you. As a matter of courtesy to your beta readers, always do a self-edit before you pass your work on because, quite frankly, if all you’re doing is writing a really rotten first draft then sending it off for someone else to do the hard work then you’re a bad person. No, really, you are.

Now, you’re wondering: is it all over? You’ve self-edited, you’ve let beta readers gnaw on the entrails of your story-child, you’ve patched it up, and you’ve sent this new, beautiful Frankenstein of a thing out into the world. If you’re lucky, someone else will love it too, so surely the editing is over. Surely.

No.

Sorry.

An editor/publisher worth their salt will see what’s wonderful about your tale, but they’ll also see what’s been missed. They might have suggestions that will make it even better (sometimes they will have terrible suggestions, too, but that’s a subject for another post), and you will find your story is being slashed and stitched yet again.

But that is okay, because you’re a professional. You’re tough, your skin is thick, and you’re wearing your Big Person Pants so you can deal with anything. You are okay with the editing because you want your story to be something that takes a reader’s breath away, that stays with them as they go about their day long after they’ve read the last line. You are okay with the editing because it’s all part of the profession. You are okay with the editing because the whole point of editing is to make your story the best it can be.

###

May 11, 2020

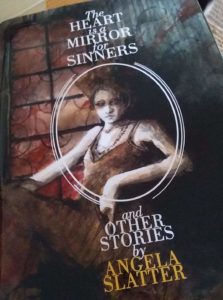

The Heart Is A Mirror for Sinners has landed!

Or at least one copy has landed in Oz: this one belongs to a friend!

Or at least one copy has landed in Oz: this one belongs to a friend!

So hopefully others will be arriving soon – including mine!

Very excited to get this glorious thing with Daniele Serra’s artwork!

#theheartisamirrorforsinners

#pspublishing

#angelaslatter