Angela Slatter's Blog, page 20

October 2, 2019

Heading into Halloween 2019

If it’s the second year you do it, it’s totally a tradition, right?

If it’s the second year you do it, it’s totally a tradition, right?

So, as I did last year, here are links to all my spooky stories that you can read online for free. They’re not all nice, so be warned. Most are witchy or witch-adjacent

This year’s additions (1. I do like cats, they just did not fare well in this story; 2. Muy Gothic; 3. Ah, yeah, blood porridge):

The Heart is a Mirror for Sinners

And here are last year’s posts:

September 30, 2019

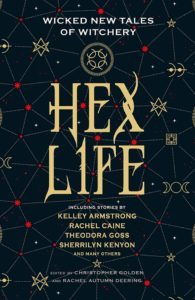

Happy Book Birthday, Hex Life!

As it’s already October 1st in Australia, Hex Life is having its birthday! Edited by the fab Christopher Golden and equally fab Rachel Autumn Deering, this magnificent tome contains WICKED NEW TALES OF WITCHERY! Go! Buy! Read! Pick yours up at your favorite bookseller.

As it’s already October 1st in Australia, Hex Life is having its birthday! Edited by the fab Christopher Golden and equally fab Rachel Autumn Deering, this magnificent tome contains WICKED NEW TALES OF WITCHERY! Go! Buy! Read! Pick yours up at your favorite bookseller.

Oh, hey, I’m ToC buds with Helen Marshall again! Hi, Helen.

Ania Ahlborn

Kelley Armstrong

Amber Benson

Chesya Burke

Rachel Caine

Kristin Dearborn

Rachel Autumn Deering

Tananarive Due

Theodora Goss

Kat Howard

Alma Katsu

Sherrilyn Kenyon

Sarah Langan

Helen Marshall

Jennifer McMahon

Hillary Monahan

Mary SanGiovanni

Angela Slatter

September 26, 2019

New Two-Book Deal!

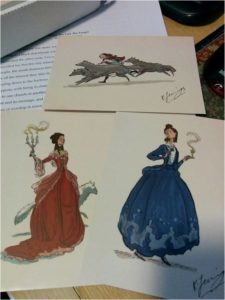

Art by Kathleen Jennings

I’m absolutely delighted to say that, thanks to the excellent work of my beloved agent Meg Davis (Ki Agency), I’ve signed a two-book deal with Cath Trechman of Titan Books.

The novel currently known as Blackwater will be published in 2021 and the novel currently known as Morwood will be published in 2020. Both books are gothic fantasies set in the same universe as the Sourdough and Bitterwood mosaic collections, the novella Of Sorrow and Such, and the upcoming The Tallow-Wife and Other Tales mosaic.

More details (like covers) as they come to hand.

September 24, 2019

Dilatando Mentes

I’m absolutely delighted to say that Sourdough and Other Stories will be translated into Spanish by the lovely folks at Dilatando Mentes (“Expanding Minds”) Editorial! Sourdough will be published in Spanish in 2021, and gradually all my other single author collections as well.

I’m absolutely delighted to say that Sourdough and Other Stories will be translated into Spanish by the lovely folks at Dilatando Mentes (“Expanding Minds”) Editorial! Sourdough will be published in Spanish in 2021, and gradually all my other single author collections as well.

This is the gorgeous English language version published by the wonderful Tartarus Press in 2010.

August 30, 2019

Morwood

I’ve hit the halfway point on my new novel, Morwood, so I thought I’d share the first chapter and the piece of art that inspired the story. This painting is by Ruth Sanderson and I first saw it at WFC in Washington in 2014, I think.

I’ve hit the halfway point on my new novel, Morwood, so I thought I’d share the first chapter and the piece of art that inspired the story. This painting is by Ruth Sanderson and I first saw it at WFC in Washington in 2014, I think.

Morwood

by Angela Slatter

Chapter One

My previous three weeks had featured a long series of carriages; conveyances of varied age, cleanliness and distinction, much like my fellow passengers. From Whitebarrow to Briarton, from Lelant’s Bridge to Angharad’s Breach, from decaying Lodellan where fires still smouldered to Cwen’s Ruin, from Bellsholm to Ceridwen’s Landing, and all the tiny loveless places in between. A circuitous route, certainly, but then I have my reasons. And this afternoon, the very last of those carriages finally deposited me at my goal before trundling off to the village of Morwood Tarn.

Or rather, at the gateway to my goal, and there now remains a rather longer walk than I would have wished at such a late hour and with such luggage as I carry. Yet, having waited with some foolish hope for someone to come collect me, in the end I accept that I’ve no better choice than shanks’ pony. My steamer case I push beneath some bushes just inside the tall black iron gates with the curlicued M at their apex (as if anyone might wander past and take it into their heads to rifle through my meagre possessions). The satchel with my notebooks is draped across my back, and the carpet bag with its preciously cargo I carry in one hand, then the other for it weighs more than is comfortable. I’m heartily sick of hefting it, but remain careful as always, solicitous of the thing that has kept me going for two years (some before that, if I am to be honest).

The rough and rutted track leads off between trees, oak and yew and ash, so tall and old that they meet above me in a canopy. I might have appreciated their beauty more if it had been earlier in the day, had there been more light, had it been summer rather than autumn, and had my coat been of better quality. And certainly if I’d not, soon after setting off deeper into the estate, begun to hear noises in the undergrowth by the side of the drive.

I do not walk faster, though it almost kills me to maintain the same steady pace. I do not call out in fear, demanding to know who is there. I do, however, pat the deep right-hand pocket of my skirt to make sure the long knife is there. I have walked enough darkened streets in dreadful towns to know that fear will kill you faster than a blade to the gut or a garrotte to the throat.

Whatever it is has stealth, but somehow I sense it makes just enough noise on purpose that I might be aware of its presence. Occasional snuffles and wuffles that must seem quite benign, but which are not when their source is defiantly out of sight. Some moments I catch a scent on the breeze, a musky rich odour like an animal given to feeding on young meat and sleeping in dens, and that threatens to turn my belly to water. I lift my chin as if the sky is not darkening with storm clouds, as if I am not being stalked, as if my heart is not pounding so hard anyone within a mile of me can hear it. But I keep my steady, steady pace.

At last, I step out from beneath the twisting, turning canopied road and get my first sight of the manor house spread out before me. I pause on the gravel drive and stare, despite the knowledge that something remains behind me, somewhere in the trees. I take a deep breath, give a sigh I didn’t know was waiting in me.

It might have appeared quite simple, the structure, if approached from the front: almost slender-looking, two storeys of pale grey almost silver stone and an attic, but I’m coming at it on an angle and can see that the manor is deeper than it is wide. It digs back into the landscape and I wonder how many rooms there might be. There are banks of diamond-paned windows of coloured glass: a strange and expensive adornment. Whatever candles are lit inside on this drear day make the windows glow, an eldritch rainbow; I was not expecting that. In front are flowering tiered gardens, three, leading up to ten steps and a small porch, and thence to a door of honey-coloured wood set beneath a pointed stone arch. A duck pond lies to the left, and to the right flows a stream, too broad too jump but too narrow to count as a river. I wonder if it ever floods.

Lighting flashes, great white streaks of fire casting themselves across the vault of the world.

Behind the house itself is a smallish building, charcoal coloured, of such a size as might contain four rooms. It has a tall chimney, and I can make out a lightning rod affixed there too. I wonder at that, but am more hopeful it might be to my advantage. A waterwheel is attached to the side, fed by the not-quite-stream-not-quite-river, yet the place does not appear to be a mill.

Once again, the lightning flashes, in quick succession striking the ground in two places in front of me, and hitting a third time on an old yew tree not far away. It stands on its own, a lone sentinel by the side of the drive, and it burns so quickly that I’m astonished rather than afraid. I’d stay to watch, too, except the heavens open at last and thick angry drops fall hard and inescapable. In spite of everything, I smile: the storms of the region will serve me well. From the undergrowth behind me there comes a definite growl, all trace of sneakery and concealment gone.

Finally, I run.

I leave the drive, which meanders back forth down a gentle slope to the manor house, and take the shortest route over the rolling lawn. The journey would have been less fraught had I not been concerned with rolling an ankle and clutching the carpet bag so tightly that my ribs bruised against its contents. I arrive at the entrance no less wet than if I’d simply strolled. My progress has obviously been noted as the door is pulled open before I set foot on the first step.

Inside that door, a blaze of light and a tall man waiting there, attired in black, a long pale face, and thinning blond hair scraped back over his scalp. For all his skeletal demeanour he wears a gentle smile and his eyes, deep-set, are kind. His hands are raised, gesturing for me to hurry, hurry.

Just before I enter beneath the archway, I glance over my shoulder, at the lawn and gardens across which I’ve come. Lightning flares yet again and illuminates the grounds, silvering a strange hunched silhouette back up on the curve of the drive, and I think of … something. Something large but of indeterminate shape, something I cannot quite place, nor does its colour even remain in my memory; there’s only the recollection of red eyes. Resolute though shivering with more than cold, I cross the threshold.

The entry hall is surprisingly small, not grand at all, but well-lit; a silken rug like a field of flowers takes up part of the floor space and I make a point not to step on it with my muddy shoes. There are small pieces of furniture, plain occasional tables, a single cherry wood chair, an umbrella stand hollowed from a sparkling rock of some sort, a rosewood hallstand bearing scarves and a parasol, but little else. Closed doors with ornate knobs lead left and right. The burnished staircase to the upper levels is quite narrow, its carved newel posts are the heads of girls with nascent antlers on their foreheads; on the landing partway up there’s an enormous stained-glass window.

‘Miss Todd,’ said the man with certainty; no surprise, really, unless the Hall is frequented by random young women on a daily basis. He waves his hands as if doing so might squeeze the moisture from my thin jacket and thick skirts. I catch sight of my reflection in the enormous mirror that is the centrepiece of the hallstand. My tiny green silk hat appears to have melted, and I can feel the extra weight of the rain in the thick braided bun of my mousy hair. It will take hours to dry. My face is pale and I appear ghostly, although I’ve never felt so triumphant in my life. I glance away before I can examine too closely the look in my own eyes, and blink, hold the closure for a few moments to compose myself so the man cannot see inside me either.

‘Yes,’ I say and it feels not enough. ‘I’m Asher Todd.’

‘I am Burdon. We did not expect you until tomorrow, my dear Miss Todd.’ His hands clasp together like penitent wings. ‘I do apologise, we’d have had Eli meet you with the caleche. Although given the current weather perhaps the caleche would not have offered much protection.’

‘Ah, the walk was refreshing, Mr Burdon, I’ve been trapped in coaches and carriages for days’ ? weeks ? ‘the open air did me good.’ I twist the ring on the middle finger of my right hand, which is slippery from the rain. I dab at it ineffectually with the least soaked part of my skirt, trying to make it less slippery for I cannot afford to lose it.

‘Just Burdon, Miss Todd. Well, I hope you don’t take a chill, the family would not be best pleased were you to fall ill from our neglect.’ He gives a little bow, strangely sweet. ‘Come along, I shall take you to your rooms.’ He eyes the carpet bag clutched to my side, the satchel dripping noisily on the flagstones. ‘Is that everything?’

‘Oh no. My trunk.’ I frown. ‘I left it by the gate.’

Burdon looks over my shoulder and juts his chin. I turn to see a figure stooped to pass beneath the stone arch of the door, my steamer trunk nestled on a broad shoulder as if it were no more than a box of kindling.

The figure gently puts the trunk on the fine rug as if it weren’t gushing with rain, then shakes like a dog. An oilskin cloak and a broad-brimmed hat are removed with a great cascade of droplets, and the shape resolves into a tall young man with ruddy hair, blue eyes and stubbled chin. He glances at me, then away as if I hold no interest.

‘Eli Bligh,’ he says and at first I think the use of a full name is an introduction, but no: a reprimand. ‘Mrs Charlton’ll not be pleased at that.’ Mr Burdon nods meaningfully at the small lake that has collected on the floor.

Eli shrugs. ‘To the lilac room?’

‘If you please.’

Eli hefts my trunk once more, as if it contains more burdensome than feathers, not books and boots and frocks and carefully wrapped bottles and a basalt mortar and pestle blessed by the Witches of Whitebarrow. He turns on a heel and is gone up the polished staircase before Burdon and I even take a step to follow; as he passes I catch a scent of port-wine pipe smoke and something I cannot quite place. The butler’s hand touches my shoulder but lightly, to direct me upwards.

‘It’s a good thing you got to us before evening fell, the estate can be a dangerous place for those unfamiliar with the lay of the land.’ He smiles to take away any suggestion of fear mongering. ‘I daresay you’ll be an old hand soon enough and learn our ways.’

‘Thank you, Burdon.’ Using a person’s last name thus, speaking as if he were my servant is not natural to me; it isn’t the way I was raised. ‘And the family …?’

‘At a fete in Morwood Tarn,’ he says, then glances through the great stained-glass window as we step onto the landing; closer, I can see it’s a battle scene between angels and wolves, now brilliant as the lightning sparks outside, now dull as it dies. ‘Although I daresay they’ll have taken sheltered somewhere to avoid the storm.’

‘Ah.’

‘Just between me and thee, Miss Todd, if I were you I would take the opportunity to rest this evening. You’ll be earning your coin soon enough with those three children. Time enough to meet everyone on the morrow.’ He smiles fondly to let me know they’re not entirely monsters, then the expression stales. ‘And I’ve no doubt Master Luther will put you through your paces as well.’

I look askance at him, but he merely smiles again and presses my elbow: Go left.

Up on the first floor is a small pretty room (so, no attic servants’ hideaway for me); it’s cold but there’s a hastily-lit fire fresh in the grate but no sign of who set it. . The armoire, dressing table and secretaire are all in a pale coloured wood; by the fire are an armchair and a small table with a tray on it: a bowl of steaming stew, a plate of bread, a single small cake, a glass of what looks like tokay await, and my stomach rumbles. The curtains are a washed-out purple, as are the draperies around the bed. And there is a small crystal bowl of dried lilac on the bedside table with mother-of-pearl inlay, so the air is lightly scented. My trunk is at the foot of the bed, and Eli is gone but for that hint of pipe smoke.

I enter the room but Burdon does not follow. Turning, I look at him and he bows, a sweet courtly gesture.

‘I trust you will be comfortable here, and perhaps even happy with us.’ He smiles again. ‘Should you need anything, the cord by the fireplace will bring someone to you. Sleep well, Miss Todd.’

‘Thank you, Burdon,’ I say, thinking I won’t sleep for an age; then I glance out the windows and see that night has fallen whilst I paid no attention. I’m aware of the door closing behind him as I stare at the rain throwing itself against the glass as if it would burst into the room if it could. As I hear the click of the snib I’m overcome with exhaustion. There is an armchair by the fire and I stumble to it, a shaking overtaking my entire body and I think I will sick, right here in this pretty room. I let the carpet bag slide to the floor, there’s the gentle thud of the contents on the rug, not too much of a protest, and I slump.

After a while, the shaking subsides, the roar in my head subsides, but my stomach is still all-at-sea, so I break off a piece of bread and stuff it into my mouth like an urchin. It’s salty and sweet, and soon I’ve eaten it all too quickly. Then the stew, which is delicious, meaty and rich with red wine. The tokay and the seed cake I leave for later so as not to make myself sick.

I’m drowsing in the chair, one side of me dried by the fire, the other still sodden and cold, when there’s a knock at the door. I call out, ‘Yes?’ but there is no answer, so I heave myself upward and go to answer.

No one is there.

I step into the long corridor ? unlike the ground floor, the first is but dimly lit ? and looked left and right. Another door was open, partway along, so I tiptoed towards it. Inside there was a bathtub, clawfooted, steam rising from it.

But again, no sign of who drew it.

I shrug; I will take it.

Such a beginning is mine at Morwood Grange.

***

August 28, 2019

Repost: Your Writing is Not You – or How to Interpret/Deal with Writerly Rejections

I’ve written before about rejections and how to handle the dent they make in your self-esteem, and I think it’s advice that bears revisiting from time to time. One thing any writer needs to develop (apart from mad writing skills and the ability to respect the deadline) is a thick skin. Not everyone is going to like your writing. Some folk will love it, some will loathe it, some will feel neither here nor there about your hard-won wordage – the only thing you can control is yourself and your reaction.

I’ve written before about rejections and how to handle the dent they make in your self-esteem, and I think it’s advice that bears revisiting from time to time. One thing any writer needs to develop (apart from mad writing skills and the ability to respect the deadline) is a thick skin. Not everyone is going to like your writing. Some folk will love it, some will loathe it, some will feel neither here nor there about your hard-won wordage – the only thing you can control is yourself and your reaction.

The thick skin doesn’t mean that you listen to no one – after all, if someone’s correcting your spelling (and they’re correct), it’s not a matter of your artistic integrity being attacked. Be grateful and gracious, say “thank you”. Don’t be embarrassed even if the person is a bit of a douche and is trying to make you feel embarrassed – that’s their damage, not yours, their insecurity, not yours.

The thick skin means that you keep on writing even after you receive a rejection. I do know people who’ve given up after their first rejection. Don’t be one of those people. Write in spite of the rejections because you should always be writing your story – your first draft – for you. You are your first reader, your first audience member after all. We never learn anything without trying and failing – the greatest teacher in the world is failure. Writing is hard, submitting it to another’s gaze is hard, suffering the slings and arrows of outrageous editors is hard; but the important next step is to work out what went wrong. One of the ways you can do this is to read your rejections. Now some writers will laugh and call this “rejectomancy”: a form of scrying as dodgy as peering at the entrails of pigeons, but really there are genuine lessons to be taken away.

So I give you, the Hierarchy of Rejections.

The Bad Rejection

The bad rejection can be a sign of a few things. You’ve sent your sexy nurse story to a gardening magazine. This is also a lesson to research markets and read submission guidelines very carefully. Chances are you may well get a bad rejection from an overworked, underpaid, very tired and impatient editor.

Or it is possible the editor is simply not accepting any more submissions, or stories of a particular type. You might have missed the deadline. There’s also the possibility that your story sucked. It might be a mostly invitation-only anthology with just a few open sub spots, which means you’re competing against a lot of other writers (please note: this is not a reason not to try – by all means submit, it’s good practice and editors may well start to remember your name in a positive fashion).

No rejection should ever say “Please hand in your pencil/pen/quill/stylus/laptop at the door and never, ever write again”, but the sad fact is that sometimes the bad rejection may well be rude or mean. Maybe you got someone on a bad day – you didn’t do anything wrong, you just got caught in the jet stream of an editor’s bad mood (donut shipment didn’t arrive; failure of a project; pet death, etc – you don’t know what’s happening in other people’s lives, so keep a little perspective); or the intern who’s doing the slush reading has an agenda. I once got a rejection letter from the editor of a leading spec-fic magazine that did not mention my story at all, but did offer quite a lot of personal abuse because I had provided an email address for notification of rejection/acceptance in order to save trees. This editor was so moved/offended/drunk that he typed this rejection letter personally, used his own envelope, schlepped to the post office, paid for the stamps himself, and roundly abused me for forcing him to do this. Have I ever submitted to that magazine again? Will I ever submit there again? If asked/begged for a story by that magazine will I ever say “Yes”? The answer to all three questions starts with an N.

The Fair to Middling Rejection

This is your standard “thanks but no thanks” letter. It doesn’t say you’re a bad writer. It just says not this story, not now. Maybe not ever. Maybe you’ve chosen the wrong market. Maybe you need to revisit the story and do a bit of flensing. Maybe it was just not quite right. And once again, some of the reasons listed in the bad rejection section may apply. But do not be downhearted, do not vow never to submit that magazine again. Keep trying.

The Hopeful Rejection

This is the letter that is almost the same as the fair to middling rejection, except in it an editor asks if you’ll consider re-working the story, with no guarantee of acceptance. Depending on the extent of the re-writes, give it some thought. Work out if the time investment is worth it for the pay day, and for the time it will take away from working on other stories. And consider whether this re-working can be a good learning experience for you in terms of craft and editing.

The Best Rejection of All

This is the gold standard of rejection letters, the one that says “Okay, not this story, but please send another.” What this means is “This particular story is not for us, but we like your style and ability so much that we want to see something else from you – yes, you! Yes, this is an invitation to YOU. And you know what? This shows we have noticed your work; we will remember your name and, with any luck, you will now get out of the slush pile a little faster.” These are all good things, dear reader-writer; these are not cause for depression. I have known some writers to get a rejection like this and think “Well, that’s a total rejection.” No, it’s not. The door has not merely been left open, but someone has also made cookies and the beverage of your choice.

In Conclusion

Don’t just accept one rejection and assume that’s it for your writing career – your skin cannot be that thin, your ego that fragile. How many rejections are too many? How long is a piece of string? If a tree falls in the forest does anyone hear it? These are questions with either no answer or an infinite variety of answers, all of which may be right, wrong or a little of both.

How much persistence do you have? Because the best friend of talent is persistence. Personally, I give a story twenty rejections – it’s an arbitrarily chosen number. It gives me time to get a story across a variety of markets. If it gets the boot from all twenty then I look at re-writing or re-purposing the story. Sometimes the rejection letters help with this because sometimes you get that rarest of things: the rejection letter with feedback telling you why the story was not right for them. These are rare because editors of magazines, journals, anthologies, etc, don’t generally have time to provide feedback on every story they get. Nor should they have to do so. You want feedback? Join a writing group.

The main thing to remember is this: your writing is not you. At the beginning of your career especially, a rejection feels like someone saying your baby is ugly. You may well be tempted to wander around the house doing an Agnes Skinner impersonation: “A dagger! A dagger through my heart!” The greatest danger is reading a rejection letter and only picking out the negative bits and then translating that negative part into self-loathing – “I’m a bad writer! My stories suck! I’ll never make it! Waaaaaaaaaaaaaaaah!” Okay, you get to do this for fifteen minutes – time yourself, then move on. Do it in the privacy of your own home; do not howl online. Then return to writing. Send the story straight back out.

And a golden rule? Do not reply to a rejection unless it is to say “Thank you for taking the time to consider my work.” “Thank you” goes a long, long way. Don’t argue with the rejection. Don’t try to get the editor to reconsider. Don’t write back rejecting the rejection. Don’t blog about the rejection, naming and vilifying the editor – if you’re going to do that, then just save some time and shoot yourself in the foot right now (off you go, we’ll wait). Take Neil Gaiman’s advice. My favourite part is “The best reaction to a rejection slip is a sort of wild-eyed madness, an evil grin, and sitting yourself in front of the keyboard muttering “Okay, you bastards. Try rejecting this!” and then writing something so unbelievably brilliant that all other writers will disembowel themselves with their pens upon reading it, because there’s nothing left to write.”

Remember that every writer at some point suffers rejection – you’re not alone. And remember that it will happen throughout your career. You will never get to a point where no one dares reject you – and you shouldn’t want to because rejections keep you sharp, keep you learning, keep you trying.

August 27, 2019

35hrs to go!

The beautiful Winter’s Tale kickstarter has 35hrs to go.

The beautiful Winter’s Tale kickstarter has 35hrs to go.

And $800 to go before it’s fully funded, so if you’ve got some spare cash …

August 19, 2019

Winter’s Tale

Winter’s Tale is the flagship title from Twelfth Planet Press’s new imprint, Titania. Written by Nike Sulway and illustrated by Shauna O’Meara, the Kickstarter is on right now and has some excellent rewards – go here and support it! Get an awesome book and other stuffs!

Winter’s Tale is the flagship title from Twelfth Planet Press’s new imprint, Titania. Written by Nike Sulway and illustrated by Shauna O’Meara, the Kickstarter is on right now and has some excellent rewards – go here and support it! Get an awesome book and other stuffs!

Today, TPP publisher Alisa Krasnostein talks about the new imprint and Winter’s Tale.

What was the inspiration behind Titania?

My dear friends Kate Gordon and Deb Kalin approached me with the idea several years ago now. They had been working together developing the idea of the imprint and its focus. Both Kate and Deb have early readers in their house and had spent several years reading to their young ones. Out of that experience, they both felt that there is a very real need for more diversity and choice within children’s books. That obviously sits well within the Twelfth Planet Press mission and thus was born Titania.

How did Winter’s Tale come together?

Kate and Deb fleshed out the imprint – naming it and approaching Kathleen Jennings to draw the Titania logo. They formulated the goals and objectives and once they knew what would be a Titania project, they then went ahead and approaching Nike Sulway about being involved. Nike wrote us Winter’s Tale.

Did you match Nike Sulway up with Shauna O’Meara or did they come along as a package deal?

I matched Shauna O’Meara with Nike Sulway. As a publisher, I liked the freedom of choosing who the artist would be. I’d been wanting to work with Shauna for a long while and then this project came along and I realised she would really be the perfect fit for it. And she is!

How do you feel it differs from a lot of children’s books already in the market?

Our focus is on offering children positive narratives with diverse characters. Winter’s Tale features an agender protagonist, gay adoptive parents, girls being awesome at skateboarding and sports, and a diverse ensemble cast of supporting characters. It’s a long book for a picture book and it’s aimed at an older child-aged audience. That said, my three year old has loved it since the first copies hit my house so I think Nike is right in saying it will have broad age appeal and the narrative will deepen to the age of the audience.

What’s next for Twelfth Planet Press?

Just around the corner we have a second Kickstarter crowdfunding project! We will be publishing a sequel to a really popular Defying Doomsday anthology which featured disabled and chronically ill protagonists and heroes surviving the apocalypse. Editor Tsana Dolichva is coming on board again and bringing along Katharine Stubbs to coedit Rebuilding Tomorrow which will be set further in post-apocalyptic futures when societies are working towards a new normal. Rebuilding Tomorrow will be an anthology of post-apocalyptic hope, and again centred on disabled and/or chronically ill protagonists. Writers will want to know that there will be an open reading period in January for stories. Because Defying Doomsday was so warmly received and so important to so many readers, I’m so looking forward to this sequel.

A

July 30, 2019

Meg Caddy: Devil’s Ballast

And today the truly delightful and piratical Meg Caddy takes over the blog to talk about Devil’s Ballast, Lambert Simnel as a dinner guest, and witch trials. Oh, and cats.

And today the truly delightful and piratical Meg Caddy takes over the blog to talk about Devil’s Ballast, Lambert Simnel as a dinner guest, and witch trials. Oh, and cats.

1. What do new readers need to know about Meg Caddy?

I am a cat-loving, tea-drinking, D&D-playing, cardigan-wearing, asexual, nerdy writer of YA adventure novels. New readers should probably know that my books sit right in the middle of the Venn diagram of feminism, history, and fantasy. I started writing my first book, Waer(a fantasy novel), when I was fourteen, and it was finally released by Text Publishing the year I turned twenty-four. I did an Honours thesis on pirates and piracy, and my second book Devil’s Ballast was published this May, also with Text.

2. What was the inspiration behind Devil’s Ballast?

Devil’s Ballast is historical fiction, but it focuses on the life and crimes of Anne Bonny, a real pirate who helped terrorise the Caribbean in the early 18th For some time she worked under the guise of being a boy, but eventually she was openly a woman pirate. No one knows for sure the fate of Anne Bonny, but while I was doing research for my Honours thesis I came across numerous suggestions that she settled down, married a friend of her father’s, had numerous children (one website suggested eighteen) and faded into history. These rumours have little historical evidence to support them, and they made me heartsick. It felt like the wrong end to the story. So I decided to rewrite it.

3. Is this part of an enduring love of pirates in general or a particular pirate?

I am mad for pirates. I have photos of myself every year since Year 12 dressed as a pirate for some occasion or another. There’s something incredibly alluring about the micro-societies pirates formed, maintained, and worked within, and it’s particularly interesting when you throw a female pirate into what was very much a male space. I love pirate stories in general, and I started researching generally for a pirate novel in 2010, but it was only in the last five or so years that I honed in on Anne.

4. In general, who and/or what are your writing influences, classic and modern?

I’m very lucky to be living in a time full of female fantasy writers. I grew up on Juliet Marillier (who has also been my mentor twice, and whose work I adore), Emily Rodda, Tamora Pierce, and Glenda Larke, among others. At the moment, I’ve been devouring books by VE Schwab, Leigh Bardugo, AJ Betts, Holly Black, and Anne Bishop. The focus on female fantasy protagonists, as well as men who do not necessarily model traditional masculinity, really shaped my writing. I’m also a die-hard Tolkien fan, and I love Dickens and Shakespeare. In terms of nonfiction, I draw heavily on the works of world-leading pirateologists, David Cordingly, who was kind enough to meet with me in London to chat about Anne Bonny. In a real-world, very present sense, I’m also very fortunate to live in Perth, where the Fantasy and YA/Children’s writing communities are so supportive and kind.

5. What was the first story you ever wrote?

Look, the first story I ever wrote was written on purple paper and it was about an egg named Eggelina, and my younger brother tore it in half and pinned it to my bedroom door like some sort of book serial killer, but I’m going to pretend that didn’t happen and instead talk about the LOTR knockoff I wrote when I was ten. It was called Rilla of Riddonan, and featured a small, bad-tempered woman with red hair, so I guess I was planning in advance for Anne even then. Actually, the villain was a woman named Milana, and I realised recently that an anti-hero in Waer, named Melana, matches the exact same physical description. It’s amazing how we write in echoes of ourselves sometimes. My parents told me if I edited the book, typed it up, and approached it professionally, they would have it properly bound and we could have a book launch – so my twelfth birthday party was a book-launch party, and I made everyone dress up as characters from Lord of the Rings. My younger brother built a catapult and we literally launched the book – just as we did for Devil’s Ballast in May.At that first book launch when I was twelve, I realised I wanted to make a living as a writer.

6. What scares you?

6. What scares you?

It’s a little banal and probably funny to people who have read Devil’s Ballast, but I’m terrified of sharks, octopi, and any number of other beasties that live in the ocean. But I also have anxiety, which means that on any given day I might be very frightened of being late, of choosing the wrong thing to eat for lunch, of dying alone, or of leaving the oven on accidentally. Fear is a close friend of mine, and though it might make me show up for a book talk three hours early it also drives me to be punctual, hard-working, and polite. I’m learning to find a good balance where fear is concerned, because it’s not always a bad thing to be afraid.

7. Who is your favourite fictional villain?

My favourite fictional villain swaps and changes a lot, but Javere from Les Miserables is always a constant. I like his rigidity, his desperate belief that he is in the right, and his inability to compromise his ideals with reality. His black-and-white thinking is his own undoing, as well as a danger to the protagonists, and I think that rings true. I tried to capture a little of his spirit for Jonathan Barnett, the antagonist in Devil’s Ballast.

8. You can invite five people, living or dead, to dinner ? who makes the cut?

If I’m inviting five people to dinner, it’s probably either my five family members or my D&D group, so I’m going to cut them out of the running for the sake of this question. I’m also not inviting Anne Bonny, because you know that girl is going to get drunk and start a fight, or dance on the table and break all the plates. So I’d invite people I want to write about. Jennet Device. Grace O’Malley. Nathaniel Mist. Lambert Simnel. Anne Brontë.

9. Jane Austen or Charlotte Bronte? Explain your choice.

I love Austen and Brontë, don’t get me wrong, but I’m going to have to add an option here and go for Mary Shelley, Queen Spooky Bitch.

10. What is next for Meg Caddy?

I’m working on a book set in early 17th century England, about two bizarre witch trials and a young girl named Jennet Device. It’s a historical fantasy. It’s early stages yet, but so far it is Spooky and full of demons, so I’m having a lot of fun.

July 12, 2019

Blackwater

As always art by Kathleen Jennings coz wolves and candlesticks and pouffy skirts …

So, I spent most of last year and the first few months of this year working on a novel called Blackwater. It’s a gothic fantasy set in the same world as the Sourdough and Bitterwood mosaics, and I thought I would share the first chapter with you. Hopefully more news on this next week …

Chapter One

See this house perched not so far from the granite cliffs? Not so far from the promontory where once a church was built? It’s very fine, the house. It’s been here a long time (far longer than the church, both before and after), and it’s less a house really than a sort of castle now. Perhaps “fortified mansion” describes it best, an agglomeration of buildings of various vintages: the oldest is a square tower from when the family first made enough money to better their circumstances. Four storeys, an attic and a cellar in the middle of which is a deep, broad well. You might think it to supply the house in times of siege, but the liquid is salty and part way down, below the water level, you can see (if you squint hard by the light of a lantern) the silver crisscross of a grid to keep things out or in. It’s always been off-limits to the children of the house, no matter that its wall is high, far higher than a child could accidentally tip over.

The tower’s stone – sometimes grey, sometimes gold, sometimes white, depending on the time of year, time of day and how much sun is about – is covered by ivy of a strangely bright green, winter and summer. To the left and right are wings added later, suites and bedrooms to accommodate the increasingly large family. The birth date of the stables is anyone’s guess, but they’re a tumbledown affair, their state perhaps a nod to lately decaying fortunes.

Embedded in the walls are swathes of glass both clear and coloured from when the O’Malleys could afford the best of everything. It lets the light in, but cannot keep the cold out, so the hearths throughout are enormous, big enough for a man to stand upright or an ox to roast in. Mostly now, however, the fireplaces remain unlit and the dormitory wings are empty of all but dust and memories; only three suites remain inhabited, and one attic room.

They built close to the cliffs – but not too close for they were wise the first O’Malleys, they knew how voracious the sea could be, how it might eat even the rocks if given a chance – so there are broad lawns of green, a low wall almost at the edge to keep all but the most determined, the most stupid, from toppling over. Stand on the stoop of the tower’s iron-banded door (shaped and engraved to look like ropes and sailors’ knots). Look ahead and you can see straight out to sea; turn to right but a little and there’s Breakwater in the distance, seemingly so tiny from here. There’s a path, too, winding back and forth on itself, an easy trail down to a pebbled shingle that stretches in a crescent. At the furtherest end is a sea cave (or was before a collapse, the date of which no one can recall), a tidal thing you don’t want to be caught in at the wrong time. A place the unwary have gone looking for treasure as rumours abounded that the O’Malleys smuggled, committed piracy, hid their ill-gotten gains there until they could be safely shifted elsewhere and exchanged for gold to line the family’s already overflowing coffers.

They’ve been here a long time, the O’Malleys, and the truth is that no one knows where they were before. Equally no one can remember when they weren’t around, or at least spoken of. No one says “Before the O’Malleys” for good reason; their history is murky, and that’s not a little to do with their very own efforts. Local recounting claims they appeared in the vanguard of some lord or lady’s army, or one of those produced by the battle abbeys in the days of the Church’s more intense militancy, perhaps one marching to or from the cathedral-city of Lodellan when its monarchs fought for land and riches. Perhaps they were soldiers or perhaps they trailed along behind like camp-followers and scavengers, gathering what they could while no one noticed, until they had enough to make a reputation.

What is spoken of is that they were unusually tall even in a place where long-legged raiders from across the oceans had liberally scattered their seed. They were dark haired and dark eyed, yet with skin so terribly pale that on occasion it was muttered that the O’Malleys didn’t go about by day, but that wasn’t true.

They took the land by Hob’s Hallow and built their tower; they prospered quickly. They took more land, they gained tenants to work the land for them. There was always silver, too, in their coffers, the purest and brightest though they’d tell no one from whence it came. Next they built ships and began trading, then built more ships and traded more, roamed further. They grew rich from the seas and everyone heard tell of how the O’Malleys did not lose themselves to the water: their galleons and caravels, their barques and brigs did not sink. Their daughters and sons did not drown (or only those meant to) for they swam like seals, learned to do so from their first breath, first step, first stroke. They kept to themselves, seldom taking wives or husbands who weren’t of their extended families. They bred like rabbits, but the core of them remained tightly wound around a limited bloodline; those bearing the O’Malley name proper were prouder than all the rest.

They paid nought but a passing care for the opinion of the church and its princes, which was more than enough to set them apart from other fine families, and made them an object of unease and rumour. Yet they kept their position and their power. They were neither stupid nor fearful. They cultivated friends in the highest of high places, sowed favours and reaped the rewards of doing so, and they gathered secrets and lies from the lowest of low places. Oh! such a harvest. The O’Malleys knew the locations of all the inconvenient bodies that had been buried – sometimes purely because they’d put the bodies there themselves. They paid their own debts, made sure they collected what was theirs, and ensured all who dealt with them knew that what was owed would be returned to them one way or another.

They were careful and clever.

Even the greatest of the god-hounds found themselves, at one point and other, beholding to them. Sometimes an ecclesiastic of import required a favour only the O’Malleys could provide and so, hat in hand, he came. Under cover of darkness, of course, in a closed carriage with no regalia that might give him away, on the loneliest roads out of Breakwater to the mansion on Hob’s Hallow. He’d take a deep breath as he stepped from the conveyance, then another as he looked up at the lofty panes of glass lit from within so it seemed the interior of the tower was on fire. He’d clasp the golden crucifix suspended at his waist for fear that, upon crossing the threshold, he might find himself somewhere more infernal than expected.

More than one such man made visits over many years. Yet such men mislike owing favours to anyone – especially women and there was a time when females held the O’Malley family reins – and those very same priests offered all manner of excuses, threats and coercions trying to avoid their obligations. None of them worked, and the brethren found themselves brought to heel each and every time: an archbishop or other lordly cleric was unseated and moved on like some common mendicant, and the smile on the lips of the matriarch was wide and red.

It was the sort of loss – an outrage – that had never been forgotten, not in several hundred years, and it was unlikely to ever be. Indeed, the church’s memory is long and unsleeping, and in each successive generation one of its sons at least has sought a way to make the family pay. No matter that the O’Malleys had given a child to the church for as long as anyone could recall, that they paid more than their tithes required, and maintained several almshouses in the city. They even had a pew with their name on it in Breakwater’s cathedral where they sat every Sunday whenever in attendance at the townhouse they maintained in one of the fancier districts.

An insult once given to the church was never forgotten nor forgiven, and generations of godly men had devoted a good deal of their lives to ill-wishing the O’Malleys past, present, and future. Much effort and energy were consecrated to the cursing of the name, gossiping about the source of their prosperity, and plotting to take it from them. Many was the head shaken in rue that pyres and pokers were not options available as a means of enforcing conformity in this particular instance – the webs woven by the clan were too strong to be evaded or undermined.

It wasn’t only the more godly members of Breakwater society at odds with those who lived out on Hob’s Hallow. Those who took O’Malley charity or made good-faith bargains with them often found that the cost was much higher than could have been imagined. Some paid it willingly and were rewarded for their loyalty; those who complained or baulked were justly requited. As time went on business partners thought twice about joining O’Malley ventures, and the more cynical counted their fingers twice after shaking hands on a deal, just to make sure all digits remained. Those who married in – whether to the extended branches or the main – did so at their peril. More than a few husbands and wives were deemed untrustworthy or simply inconvenient when passion had run its course, and disposed of quietly.

There was something not quite right with the O’Malleys, they didn’t fear like others of their ilk. They, perhaps, put their faith elsewhere. Some said the O’Malleys had too much salt water in their veins to be good and god-fearing, or good anything else for that matter. But nothing could be proven, not ever.

Their dealings were discreet, but things done ill always leave echoes and stains behind. Because they’d been around for so very long, the O’Malleys’ sins built up, year upon year, decade upon decade, century upon century. Life upon life, death upon death.

The family was simply too influential to be easily destroyed but, as it turned out, they brought themselves down with neither aid nor agitation from either church or peers.

It was their bloodline that had faltered first – although no one but they knew – and their fortunes followed soon after. Fewer and fewer children were born to the O’Malleys proper, but for a while they’d not been bothered, or not overly so, for seemed like nothing more than a brief aberration. Besides, the extended families continued to multiply, and to prosper financially.

Then their ships began to sink or be taken by pirates; then investments, seemingly shrewd, were quickly proven unwise. The great fleet was whittled down to a couple of merchant vessels making desultory journeys across the seas. Almost all their affluence bled away, faster and faster until within a few generations there was just the grand mess of a home on Hob’s Hallow. There were rumours of jewellery, silver and gems buried beneath the rolling lawns – no one could believe it was all gone – but the O’Malleys had too many debts, too little capital, and their blood was running thin …

And so the family found itself much diminished in more ways than one. Unable to pay its creditors and investors, unable to give to the sea what it was owed, and with too few of other people’s secrets to use as currency, the O’Malleys were, at last, in danger of extinction.

The estate was once carefully tended by an army of gardeners and groundsmen, but now there’s only ancient Malachi – barely breathing, regularly farting dust – to take care of things. All the walled gardens are over-run, to enter them would be to risk having sleeves and skirts torn by thorns and branches with too much length and strength, and besides, their doors are sewn shut with brambles. All but one that is, the one the old woman – the last true O’Malley – uses when she seeks fresh air and solitude. In the house, Malachi’s sister, Maura – younger by a little and less given to farting – does what she can to keep the gilings and decay at bay, but she’s one woman, arthritic and tired and cross; it’s a losing battle, though she keeps her hand in with herb magic and rituals to keep the kitchen garden producing vegetables and the orchard fruiting. There are two horses to pull a rickety calash; three cows, all almost beyond giving milk; several chickens whose lives are likely to be short if they do not begin to take their duties more seriously. Once, there was an army of tenants who could be called upon to work the fields, but now they are few and the land has laid fallow for a very long time indeed. The great house is decaying and the great curved gates at the entrance to the estate have not been closed in a decade for fear any movement will tear them from their rusted hinges.

There’s just a single daughter left of the household, whose surname isn’t even O’Malley, her mother having committed the multiple sins of being an only child, a girl, insisting from sheer perversity on taking her husband’s name, and then dying without producing further offspring. Worse still: this husband had no O’Malley lineage – not a drop – so the daughter’s blood was thinned once again. She’s twenty-one, this girl, a woman really, raised mostly in isolation, taught to run a house as if this one isn’t a ruin waiting to fall, with a dying family (decreased yet again by a recent death), no fortune, and no prospects of which to speak.

There’s an old woman, though, with plans and plots of long gestation; and there’s the sea, which will have her due, come hell or high water; and there are secrets and lies which never stay buried forever.

***