Maggi Andersen's Blog, page 69

June 25, 2012

Aah, the joy of procrastination!

Published on June 25, 2012 18:47

June 24, 2012

THE ETIQUETTE OF THE FAN IN GEORGIAN LONDON

When parties and balls became fashionable in England in the Elizabethan period, the fan became de rigueur. The heavy, hot atmosphere of unwashed overdressed people jammed into a candlelit room made them a necessity to keep one's makeup from running. At first paddle-shaped or made from feathers, they were fairly uninspiring until the arrival of the Huguenots.

After Jacob Chassereau settled in London fans became a work of art, enlivened by the Chinese export market. Fans were then constructed uniformly, and no bigger than twelve and a half inches long. The decoration was chosen by the lady. [image error]Painters specialized in decorating fans. In England the shepherds and nymphs of Watteau and later Boucher were popular. (Watteau himself painted fans, including the bridal fan of Adelaide of Savoy in 1709.) In 1711, the craze for expensive fans reached such proportions that Joseph Addison felt the need to mock it roundly in his coffee house publication, The Spectator. His excellent article, 'advertising' his Academy for the Instruction of the Use of the Fan explains how he drills young ladies in fan etiquette in a military fashion. The Fluttering of the Fan is the last, and indeed the master-piece of the whole Exercise; but if a lady does not misspend her time, she may make herself mistress of it in three months...There is the angry flutter, the modest flutter, the timorous flutter, the confused flutter, the merry flutter, and the amorous flutter...I have seen a fan so very angry, that it would have been dangerous for the absent lover who provoked it to have come within the wind of it...I need not add, that a fan is either a prude of coquet according to the nature of the person who bears it.p.s. I teach young gentlemen the whole art of gallanting a fan.Spectator, no. 102He mocked the 'Language of the Fan'. The Rotari portrait of circa 1750 of the girl with the butcher's hands seems to indicate there was some kind of message to be imparted by particular postures. [image error]Whether such a language was ever used by young ladies at fashionable parties was possibly only a romantic notion: Common themes:Fan closed, tip to lips: we are overheardDitto, tip to right cheek: yesDitto, tip to left cheek: noDitto, tip to forehead: you are out of your mindChin on tip: you annoy meDitto, tip to heart: I love youLower open fan until pointing at the ground: I hate you

In 1711, the craze for expensive fans reached such proportions that Joseph Addison felt the need to mock it roundly in his coffee house publication, The Spectator. His excellent article, 'advertising' his Academy for the Instruction of the Use of the Fan explains how he drills young ladies in fan etiquette in a military fashion. The Fluttering of the Fan is the last, and indeed the master-piece of the whole Exercise; but if a lady does not misspend her time, she may make herself mistress of it in three months...There is the angry flutter, the modest flutter, the timorous flutter, the confused flutter, the merry flutter, and the amorous flutter...I have seen a fan so very angry, that it would have been dangerous for the absent lover who provoked it to have come within the wind of it...I need not add, that a fan is either a prude of coquet according to the nature of the person who bears it.p.s. I teach young gentlemen the whole art of gallanting a fan.Spectator, no. 102He mocked the 'Language of the Fan'. The Rotari portrait of circa 1750 of the girl with the butcher's hands seems to indicate there was some kind of message to be imparted by particular postures. [image error]Whether such a language was ever used by young ladies at fashionable parties was possibly only a romantic notion: Common themes:Fan closed, tip to lips: we are overheardDitto, tip to right cheek: yesDitto, tip to left cheek: noDitto, tip to forehead: you are out of your mindChin on tip: you annoy meDitto, tip to heart: I love youLower open fan until pointing at the ground: I hate you

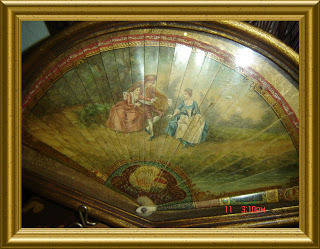

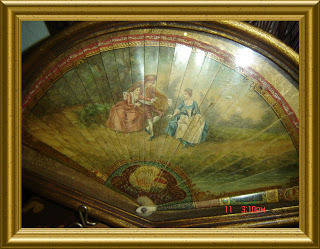

Vernis Martin fan

Vernis Martin fan

REGENCYDuring the Regency era, every lady of fashion carried a fan in her reticule. She would slip it over her wrist at a ball or evening party but used was less for flirtation. The elegant accessory was used to provide relief from the heat of the ballroom. Folding fans with multiple elaborately decorated sticks, known as brise fans, were among the most popular and were often articles of great beauty. The Vernis Martin fans were so-called because of their varnished decoration. They were hand-painted, often with oriental scenes. Developed by the four Martin brothers, they were highly prized.The sticks were made of wood, ivory, mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell metal or lacquered wood, gold with leaves of silk, crape, lace, chicken skin, paper or lamb's/kid's skin. Regency fans were usually between six and ten inches long.

Excerpt from The Reluctant Marquess:

Brigitte picked up a fan painted with flowers. “And the fan,

my lady. No lady is without one. You must flirt with it.”

“Flirt?”

“Like this.” Brigitte opened the fan, displaying a lovely

painted rural scene and fluttered it before her face. “Like a

coquette, oui?”

“I suppose so,” Charity said doubtfully.

“It is called the amorous flutter,” Brigitte said, warming

to her theme. “There is also the angry flutter, like this.” She

snapped it shut. “The modest miss, oui, like this? A merry

lady, like this….”

She expertly twirled the fan.

“Oh stop,” Charity said, laughing. “I shall never feel

comfortable doing any of that.”

“But that is the way of society ladies,” Brigitte said. “I learnt

it in France from the Countess De Avignon.”

“Well, perhaps I’ll ease into it gradually.” Charity relented

at the disappointed moue on Brigitte’s lips, and Brigitte

immediately brightened, handing her the fan and her reticule.

BUY LINK: AMAZON KINDLESources: Georgette Heyer's Regency World by Jennifer Kloester, Sourcebooks. Georgian London by Lucy Inglis Georgian London the book will be available in hardback in the summer of 2012, published by Penguin Books. http://www.georgianlondon.com

After Jacob Chassereau settled in London fans became a work of art, enlivened by the Chinese export market. Fans were then constructed uniformly, and no bigger than twelve and a half inches long. The decoration was chosen by the lady. [image error]Painters specialized in decorating fans. In England the shepherds and nymphs of Watteau and later Boucher were popular. (Watteau himself painted fans, including the bridal fan of Adelaide of Savoy in 1709.)

In 1711, the craze for expensive fans reached such proportions that Joseph Addison felt the need to mock it roundly in his coffee house publication, The Spectator. His excellent article, 'advertising' his Academy for the Instruction of the Use of the Fan explains how he drills young ladies in fan etiquette in a military fashion. The Fluttering of the Fan is the last, and indeed the master-piece of the whole Exercise; but if a lady does not misspend her time, she may make herself mistress of it in three months...There is the angry flutter, the modest flutter, the timorous flutter, the confused flutter, the merry flutter, and the amorous flutter...I have seen a fan so very angry, that it would have been dangerous for the absent lover who provoked it to have come within the wind of it...I need not add, that a fan is either a prude of coquet according to the nature of the person who bears it.p.s. I teach young gentlemen the whole art of gallanting a fan.Spectator, no. 102He mocked the 'Language of the Fan'. The Rotari portrait of circa 1750 of the girl with the butcher's hands seems to indicate there was some kind of message to be imparted by particular postures. [image error]Whether such a language was ever used by young ladies at fashionable parties was possibly only a romantic notion: Common themes:Fan closed, tip to lips: we are overheardDitto, tip to right cheek: yesDitto, tip to left cheek: noDitto, tip to forehead: you are out of your mindChin on tip: you annoy meDitto, tip to heart: I love youLower open fan until pointing at the ground: I hate you

In 1711, the craze for expensive fans reached such proportions that Joseph Addison felt the need to mock it roundly in his coffee house publication, The Spectator. His excellent article, 'advertising' his Academy for the Instruction of the Use of the Fan explains how he drills young ladies in fan etiquette in a military fashion. The Fluttering of the Fan is the last, and indeed the master-piece of the whole Exercise; but if a lady does not misspend her time, she may make herself mistress of it in three months...There is the angry flutter, the modest flutter, the timorous flutter, the confused flutter, the merry flutter, and the amorous flutter...I have seen a fan so very angry, that it would have been dangerous for the absent lover who provoked it to have come within the wind of it...I need not add, that a fan is either a prude of coquet according to the nature of the person who bears it.p.s. I teach young gentlemen the whole art of gallanting a fan.Spectator, no. 102He mocked the 'Language of the Fan'. The Rotari portrait of circa 1750 of the girl with the butcher's hands seems to indicate there was some kind of message to be imparted by particular postures. [image error]Whether such a language was ever used by young ladies at fashionable parties was possibly only a romantic notion: Common themes:Fan closed, tip to lips: we are overheardDitto, tip to right cheek: yesDitto, tip to left cheek: noDitto, tip to forehead: you are out of your mindChin on tip: you annoy meDitto, tip to heart: I love youLower open fan until pointing at the ground: I hate you Vernis Martin fan

Vernis Martin fanREGENCYDuring the Regency era, every lady of fashion carried a fan in her reticule. She would slip it over her wrist at a ball or evening party but used was less for flirtation. The elegant accessory was used to provide relief from the heat of the ballroom. Folding fans with multiple elaborately decorated sticks, known as brise fans, were among the most popular and were often articles of great beauty. The Vernis Martin fans were so-called because of their varnished decoration. They were hand-painted, often with oriental scenes. Developed by the four Martin brothers, they were highly prized.The sticks were made of wood, ivory, mother-of-pearl, tortoiseshell metal or lacquered wood, gold with leaves of silk, crape, lace, chicken skin, paper or lamb's/kid's skin. Regency fans were usually between six and ten inches long.

Excerpt from The Reluctant Marquess:

Brigitte picked up a fan painted with flowers. “And the fan,

my lady. No lady is without one. You must flirt with it.”

“Flirt?”

“Like this.” Brigitte opened the fan, displaying a lovely

painted rural scene and fluttered it before her face. “Like a

coquette, oui?”

“I suppose so,” Charity said doubtfully.

“It is called the amorous flutter,” Brigitte said, warming

to her theme. “There is also the angry flutter, like this.” She

snapped it shut. “The modest miss, oui, like this? A merry

lady, like this….”

She expertly twirled the fan.

“Oh stop,” Charity said, laughing. “I shall never feel

comfortable doing any of that.”

“But that is the way of society ladies,” Brigitte said. “I learnt

it in France from the Countess De Avignon.”

“Well, perhaps I’ll ease into it gradually.” Charity relented

at the disappointed moue on Brigitte’s lips, and Brigitte

immediately brightened, handing her the fan and her reticule.

BUY LINK: AMAZON KINDLESources: Georgette Heyer's Regency World by Jennifer Kloester, Sourcebooks. Georgian London by Lucy Inglis Georgian London the book will be available in hardback in the summer of 2012, published by Penguin Books. http://www.georgianlondon.com

Published on June 24, 2012 21:21

June 21, 2012

4 star review from RT Book Reviews for Hostage to Fortune

HOSTAGE TO FORTUNE

by Maggi Andersen

Genre: Historical Romance, E-book, England, France

Sensuality: HOT

Setting: 1792 England and France

RT RatingThis is an adventure not to be missed. The excitement mounts as danger appears around every corner. The devastation of the French Revolution is a backdrop to the well-executed plot. Love is in the air for three couples, but will they survive to realize their dreams?Verity is an actress whose father is in a French dungeon. To free him she must deliver Anthony Beaumont in trade. She travels to London to seduce Anthony into following her to France. She doesn’t plan on falling in love. Then, he hares off on his own to France to locate his brother-in-law. Verity follows him, reluctantly taking along his daughter who refuses to be left behind. Unfortunately, they just miss joining Anthony, as soldiers of the Revolution reach their destination ahead of them and capture him and his brother-in-law. Will everyone finally be reunited, or will they face the guillotine? (MAGGIANDERSENAUTHOR.COM

RT RatingThis is an adventure not to be missed. The excitement mounts as danger appears around every corner. The devastation of the French Revolution is a backdrop to the well-executed plot. Love is in the air for three couples, but will they survive to realize their dreams?Verity is an actress whose father is in a French dungeon. To free him she must deliver Anthony Beaumont in trade. She travels to London to seduce Anthony into following her to France. She doesn’t plan on falling in love. Then, he hares off on his own to France to locate his brother-in-law. Verity follows him, reluctantly taking along his daughter who refuses to be left behind. Unfortunately, they just miss joining Anthony, as soldiers of the Revolution reach their destination ahead of them and capture him and his brother-in-law. Will everyone finally be reunited, or will they face the guillotine? (MAGGIANDERSENAUTHOR.COM

Published on June 21, 2012 16:11

June 20, 2012

Great review of The Reluctant Marquess.

Charity Barlow wished to marry for love. The rakish Lord Robert wishes only to tuck her away in the country once an heir is produced.

Charity Barlow wished to marry for love. The rakish Lord Robert wishes only to tuck her away in the country once an heir is produced. A country-bred girl, Charity Barlow suddenly finds herself married to a marquess, an aloof stranger determined to keep his thoughts and feelings to himself. She and Lord Robert have been forced by circumstances to marry, and she feels sure she is not the woman he would have selected given a choice.

The Marquess of St. Malin makes it plain to her that their marriage is merely for the procreation of an heir, and once that is achieved, he intends to continue living the life he enjoyed before he met her.

While he takes up his life in London once more, Charity is left to wander the echoing corridors of St. Malin House, when she isn’t thrown into the midst of the mocking Haute Ton. Charity is not at all sure she likes her new social equals, as they live by their own rules, which seem rather shocking. She’s not at all sure she likes her new husband either, except for his striking appearance and the dark desire in his eyes when he looks at her, which sends her pulses racing.

Lord Robert is a rake and does not deserve her love, but neither does she wish to live alone. Might he be suffering from a sad past? Seeking to uncover it, Charity attempts to heal the wound to his heart, only to make things worse between them. Will he ever love her?

To be a penniless orphan looking for a way to make a living or be a marchioness is a decision Charity Barlow must make; to live with wealth and magnificent homes or perhaps be a governess in someone else’s home, living in the shadows and teaching someone else’s children.

It seems expedient to marry the new marquess. He's strikingly handsome and willing to postpone consummating their marriage until they get to know each other better and then only for siring an heir and a spare. Also, it's what her deceased godfather wanted. However, Charity believes marriage is a sacred institution, plus she always dreamed of marrying for love.

Robert, the new marquess of St. Malin, sees marriage as inconsequential and doesn’t believe in love. His proposal is upfront with Charity. He will marry her to keep his vast inheritance, but he will continue living the life he likes—mistress, gambling, racing, and London Society entertainment pastimes. He’s determined to keep his freedom but magnanimously offers her all the perks of being a marchioness.

Maggi Andersen takes the late nineteenth century mores of London Society, a self-centered young nobleman, and a countrified, intelligent, kind, ‘all-alone’ young woman and creates a captivating story of love—in a time when love and fidelity were SO out of fashion.

The petite, delicate Charity tackles the task of being a marchioness full-steam-ahead, hoping to make her husband love, trust, and respect her. She showcases all the fancy clothes and exquisite jewels he feels befit a rich marquess’ wife. She sits for a portrait that he commissions. Moreover, she copes with the gossip, flirting, and one-upsmanship that ebb and flow in the ton. Still, her husband is remote, though flawlessly courteous. He neglects her until she “made a mistake”. In a jealous rage, he berates her.

Wow, does he find out his Charity is no little country mouse. When he roars at her, she roars back at him with accusations that hit home—like, he's spoiled, pompous, self-centered, careless and unkind toward her.

Robert, stuck in an emotional time warp that goes back to his early teens and with a mindset of the privileged nobility struggles with “keeping his freedom” while learning to manage his estates vast wealth, and keeping his enticing little wife at bay emotionally.

As his metamorphosis makes him complete, he finally becomes a worthy hero to the generous heroine who berates herself for not being more appreciative of things he did for her before he realized he loved her.

While Maggi Andersen uses the usual elements found in romances set in this historical era in English, she weaves them together uniquely so The Reluctant Marquess sparkles and captivates. She captures the reader’s senses with delightful metaphors and compelling comparisons. The scents, sounds, etc. of London compared to those of Cornwell take the reader into the settings to feels the differences. This unique parallel is rather symbolic of how Charity and Robert’s relationship unfolds. While in London their relationship is polluted with all the trappings of Society, but in Cornwall it is fresh, clean, and pure; strong enough to find that happy-ever-after. Good entertainment.

Published on June 20, 2012 16:08

June 17, 2012

The Peterloo Massacre

This event appears in my work in progress, TAMING A GENTLEMAN SPY, so I thought I'd write more about it.

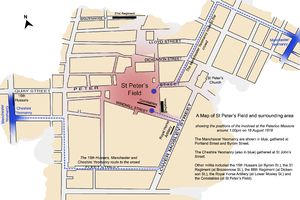

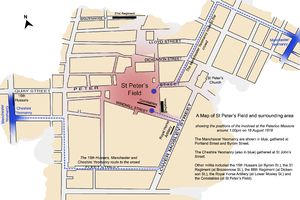

St Peter’s Field, Manchester, England.

St Peter’s Field, Manchester, England.

Map of the Peterloo Massacre

Map of the Peterloo Massacre

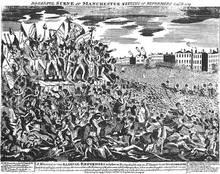

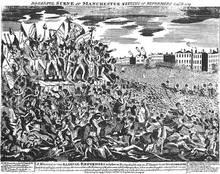

Hunt's arrest by the ConstablesIn August 1819 on a cloudless, hot summer’s day, a peaceable crowd of some 60,000 to 80,000 people gathered in St Peter’s Field (an open piece of cleared land alongside Mount Street) to hear orator, Henry Hunt speak and to demand reform of parliamentary representation. What happened next was as unnecessary as it was shocking. Cavalry charged into the crowd with sabres drawn, and in the ensuring confusion, 15 people were killed and between 400 and 700 injured.

Hunt's arrest by the ConstablesIn August 1819 on a cloudless, hot summer’s day, a peaceable crowd of some 60,000 to 80,000 people gathered in St Peter’s Field (an open piece of cleared land alongside Mount Street) to hear orator, Henry Hunt speak and to demand reform of parliamentary representation. What happened next was as unnecessary as it was shocking. Cavalry charged into the crowd with sabres drawn, and in the ensuring confusion, 15 people were killed and between 400 and 700 injured.

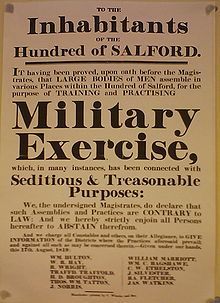

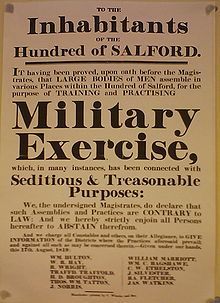

Notice to the Inhabitants of the Hundred of Salford

Notice to the Inhabitants of the Hundred of Salford

In March 1819, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe formed the Manchester Patriotic Union Society. All the leading radicals in Manchester joined the organisation. Johnson was appointed secretary and Wroe became treasurer.

The local magistrates were concerned that such a substantial gathering of reformers might end in a riot. The magistrates therefore decided to arrange for a large number of soldiers to be in Manchester on the day of the meeting. This included four squadrons of cavalry of the 15th Hussars (600 men), several hundred infantrymen, the Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry (400 men), a detachment of the Royal Horse Artillery and two six-pounder guns and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry (120 men) and all Manchester's special constables (400 men).

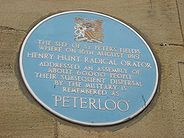

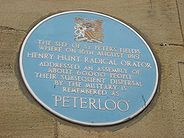

At about 11.00 a.m. William Hulton, the chairman, and nine other magistrates met at Mr. Buxton's house in Mount Street that overlooked St. Peter's Field. Although there was no trouble, the magistrates became concerned by the growing size of the crowd. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but Hulton came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in St. Peter's Field at midday. Hulton, therefore, took the decision to send Edward Clayton, the Boroughreeve and the special constables to clear a path through the crowd. The 400 special constables were therefore ordered to form two continuous lines between the hustings where the speeches were to take place, and Mr. Buxton's house where the magistrates were staying. Shortly after the meeting began, local magistrates called on the military to arrest well-known radical orator, Henry Hunt who was asked to chair the meeting, and several others on the hustings with him, and to disperse the crowd. Arrested along with Hunt for inciting a riot and imprisoned was Samuel Bamford, who led a group from his native Middleton to St. Peter’s Field. Bamford emerged as a prominent voice for radical reform. Hunt became MP for Preston 1830-33.To understand what happened in Manchester one must look at the period of economic upheaval between 1783 to 1846, when Britain shifted from being a predominantly agricultural and commercial society to being the world’s first industrial nation. Many of the most contentious political issues of the day, corn and currency laws for example, were really questions of whether government policy should be directed towards encouraging this shift, or trying to reverse it. Original blue plaque replaced in 2007

Original blue plaque replaced in 2007

Accompanying the economic changes was the most sustained and dangerous cycle of revolutionary discontent and working-class protest in British history. This prompted a few political concessions on the part of the governing aristocracy, but more significant was the emergence of governmental machinery designed to maintain law and order, which in turn led unintentionally to the foundation of the modern centralized and bureaucratic state.The power of the Crown declined significantly. Although George III (until he became incurably mad in 1810) George IV, William IV, Victoria, and her consort Albert, could all influence the course of political intrigue, the monarch’s power to control the policies of the state was severely reduced.As the scope and scale of government business increased during the long French wars, less and less passed through the monarch’s hands. Except possibly where foreign policy was concerned, the Crown was being reduced to little more than a figurehead of state. Effective power remained in the hands of a territorial aristocracy, whose representatives still dominated both Houses of Parliament. They faced an active and vociferous radical movement, particularly strong in 1792 and in the economically depressed years after the end of the war in 1815, when a period of famine and chronic unemployment came into being, exacerbated by the introduction of the first of the Corn Laws. Postwar adjustment brought depression, with agrarian disturbances, machine-breaking and revival of popular reform agitation. Two meets at Spa Fields 1816 and an attack on the Prince Regent led to suspension of Habeas Corpus and restrictions on public meetings.After the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century, Manchester began expanding at an astonishing rate in the 19th Century as part of a process of unplanned urbanization. Samuel Bamford

Samuel Bamford

Bamford, an author of poetry, led a group from Middleton to St Peter's Fields, to attend a meeting pressing for parliamentary reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws. He was arrested and charged with treason and jailed for a year. He became a voice for radical reform, but was opposed to any activism that involved physical force.

Historian, Robert Poole has called the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester one of the defining moments of its age. It left an enormous psychological scar on a polity which prided itself on its ability to contain discontents. Yet the aristocracy survived, largely because the middling ranks, terrified by the violence of the French Revolution, rejected any sort of revolutionary radicalism. The Peterloo Massacre called on the Government in 1819 to pass what is known as the Six Acts which forbade training in arms and drilling, authorized seizure of arms, simplified prosecutions, forbade seditious assemblies, punished blasphemous libels and restricted the press. Resource: The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland.

St Peter’s Field, Manchester, England.

St Peter’s Field, Manchester, England.

Map of the Peterloo Massacre

Map of the Peterloo Massacre

Hunt's arrest by the ConstablesIn August 1819 on a cloudless, hot summer’s day, a peaceable crowd of some 60,000 to 80,000 people gathered in St Peter’s Field (an open piece of cleared land alongside Mount Street) to hear orator, Henry Hunt speak and to demand reform of parliamentary representation. What happened next was as unnecessary as it was shocking. Cavalry charged into the crowd with sabres drawn, and in the ensuring confusion, 15 people were killed and between 400 and 700 injured.

Hunt's arrest by the ConstablesIn August 1819 on a cloudless, hot summer’s day, a peaceable crowd of some 60,000 to 80,000 people gathered in St Peter’s Field (an open piece of cleared land alongside Mount Street) to hear orator, Henry Hunt speak and to demand reform of parliamentary representation. What happened next was as unnecessary as it was shocking. Cavalry charged into the crowd with sabres drawn, and in the ensuring confusion, 15 people were killed and between 400 and 700 injured.

Notice to the Inhabitants of the Hundred of Salford

Notice to the Inhabitants of the Hundred of SalfordIn March 1819, Joseph Johnson, John Knight and James Wroe formed the Manchester Patriotic Union Society. All the leading radicals in Manchester joined the organisation. Johnson was appointed secretary and Wroe became treasurer.

The local magistrates were concerned that such a substantial gathering of reformers might end in a riot. The magistrates therefore decided to arrange for a large number of soldiers to be in Manchester on the day of the meeting. This included four squadrons of cavalry of the 15th Hussars (600 men), several hundred infantrymen, the Cheshire Yeomanry Cavalry (400 men), a detachment of the Royal Horse Artillery and two six-pounder guns and the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry (120 men) and all Manchester's special constables (400 men).

At about 11.00 a.m. William Hulton, the chairman, and nine other magistrates met at Mr. Buxton's house in Mount Street that overlooked St. Peter's Field. Although there was no trouble, the magistrates became concerned by the growing size of the crowd. Estimations concerning the size of the crowd vary but Hulton came to the conclusion that there were at least 50,000 people in St. Peter's Field at midday. Hulton, therefore, took the decision to send Edward Clayton, the Boroughreeve and the special constables to clear a path through the crowd. The 400 special constables were therefore ordered to form two continuous lines between the hustings where the speeches were to take place, and Mr. Buxton's house where the magistrates were staying. Shortly after the meeting began, local magistrates called on the military to arrest well-known radical orator, Henry Hunt who was asked to chair the meeting, and several others on the hustings with him, and to disperse the crowd. Arrested along with Hunt for inciting a riot and imprisoned was Samuel Bamford, who led a group from his native Middleton to St. Peter’s Field. Bamford emerged as a prominent voice for radical reform. Hunt became MP for Preston 1830-33.To understand what happened in Manchester one must look at the period of economic upheaval between 1783 to 1846, when Britain shifted from being a predominantly agricultural and commercial society to being the world’s first industrial nation. Many of the most contentious political issues of the day, corn and currency laws for example, were really questions of whether government policy should be directed towards encouraging this shift, or trying to reverse it.

Original blue plaque replaced in 2007

Original blue plaque replaced in 2007Accompanying the economic changes was the most sustained and dangerous cycle of revolutionary discontent and working-class protest in British history. This prompted a few political concessions on the part of the governing aristocracy, but more significant was the emergence of governmental machinery designed to maintain law and order, which in turn led unintentionally to the foundation of the modern centralized and bureaucratic state.The power of the Crown declined significantly. Although George III (until he became incurably mad in 1810) George IV, William IV, Victoria, and her consort Albert, could all influence the course of political intrigue, the monarch’s power to control the policies of the state was severely reduced.As the scope and scale of government business increased during the long French wars, less and less passed through the monarch’s hands. Except possibly where foreign policy was concerned, the Crown was being reduced to little more than a figurehead of state. Effective power remained in the hands of a territorial aristocracy, whose representatives still dominated both Houses of Parliament. They faced an active and vociferous radical movement, particularly strong in 1792 and in the economically depressed years after the end of the war in 1815, when a period of famine and chronic unemployment came into being, exacerbated by the introduction of the first of the Corn Laws. Postwar adjustment brought depression, with agrarian disturbances, machine-breaking and revival of popular reform agitation. Two meets at Spa Fields 1816 and an attack on the Prince Regent led to suspension of Habeas Corpus and restrictions on public meetings.After the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century, Manchester began expanding at an astonishing rate in the 19th Century as part of a process of unplanned urbanization.

Samuel Bamford

Samuel BamfordBamford, an author of poetry, led a group from Middleton to St Peter's Fields, to attend a meeting pressing for parliamentary reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws. He was arrested and charged with treason and jailed for a year. He became a voice for radical reform, but was opposed to any activism that involved physical force.

Historian, Robert Poole has called the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester one of the defining moments of its age. It left an enormous psychological scar on a polity which prided itself on its ability to contain discontents. Yet the aristocracy survived, largely because the middling ranks, terrified by the violence of the French Revolution, rejected any sort of revolutionary radicalism. The Peterloo Massacre called on the Government in 1819 to pass what is known as the Six Acts which forbade training in arms and drilling, authorized seizure of arms, simplified prosecutions, forbade seditious assemblies, punished blasphemous libels and restricted the press. Resource: The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland.

Published on June 17, 2012 18:44

Something beautiful today.

Published on June 17, 2012 18:11

June 14, 2012

Carl Sagan puts it well!

I'm busy writing How to Tame a Gentleman Spy (Book Two) The Spies of Mayfair Series and organizing promotion for Book One: A Baron in Her Bed - The Spies of Mayfair Series. I'll post some excerpts soon.

I'm busy writing How to Tame a Gentleman Spy (Book Two) The Spies of Mayfair Series and organizing promotion for Book One: A Baron in Her Bed - The Spies of Mayfair Series. I'll post some excerpts soon.

Published on June 14, 2012 16:32

June 6, 2012

Costumes Lady Sibella wears in Taming a Gentleman Spy

Published on June 06, 2012 16:55

June 1, 2012

What author and blue-eyed actor inspired Murder in Devon?

I'm visiting the Black Opal blog talking about the inspiration for writing Murder in Devon. http://www.somestoriestold.com/wpblogs/2012/05/30/inspiration-to-write-murder-in-devon/#comment-762

I'm visiting the Black Opal blog talking about the inspiration for writing Murder in Devon. http://www.somestoriestold.com/wpblogs/2012/05/30/inspiration-to-write-murder-in-devon/#comment-762

Published on June 01, 2012 16:31

May 31, 2012

This took my fancy

SHORT AND SWEET

While most statutes (in England) are long winded, the shortest seems to be from 1487, which reads: "None from henceforth shall use to multiply gold or silver, or use the craft of multiplications, and if any do the same, he shall incur the pain of felony." It seems to be warning you not to get rich quick and comes immediately before another, more straightforward, felony - that incurred by cutting the tongue or plucking out the eyes of the King's liege men.

From: The strange Laws of Old England by Nigel Cawthorne

While most statutes (in England) are long winded, the shortest seems to be from 1487, which reads: "None from henceforth shall use to multiply gold or silver, or use the craft of multiplications, and if any do the same, he shall incur the pain of felony." It seems to be warning you not to get rich quick and comes immediately before another, more straightforward, felony - that incurred by cutting the tongue or plucking out the eyes of the King's liege men.

From: The strange Laws of Old England by Nigel Cawthorne

Published on May 31, 2012 18:28