Karl Shuker's Blog, page 53

July 29, 2013

WHAT MAY BE A HITHERTO-UNDOCUMENTED SIGHTING OF THE LOCH NESS MONSTER, GIVEN TO ME BY TIM DINSDALE ON 25 JULY 1987

st1\:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) } The first Nessie book that I ever read was this one, by Tim Dinsdale, purchased for me as a child by my mother

st1\:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) } The first Nessie book that I ever read was this one, by Tim Dinsdale, purchased for me as a child by my mother Back in 1986, veteran Loch Ness monster researcher Tim Dinsdale (1924-1987) had corresponded with me in relation to a very different but equally intriguing water monster that formed the basis of my first major cryptozoological investigation – Gambo, the Gambian sea serpent. Consequently, when I attended the International Society of Cryptozoology's two-day symposium held at the Royal Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh on 25-26 July 1987, Day 1 of which was devoted to Nessie and at which Tim was one of the speakers (click here to read my reporting of this symposium), I lost no time in introducing myself to him so that I could thank him directly for his kind interest and encouragement in my own fledgling cryptozoological researches.

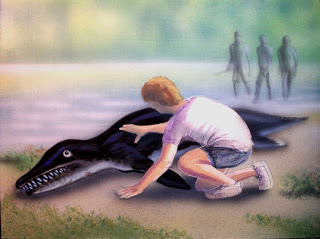

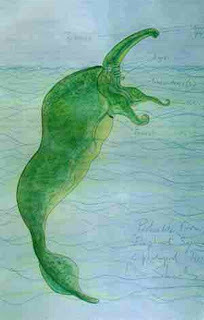

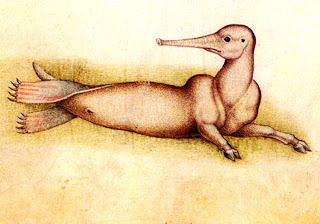

Artistic representation of the Gambian sea serpent (William Rebsamen)

Artistic representation of the Gambian sea serpent (William Rebsamen) In response, Tim gave me a copy of a most interesting Nessie sighting that an eyewitness had recently sent to him. He didn't provide me with the eyewitness's name, because he no doubt intended to publish an exclusive report of it in some future publication. Tragically, however, only a few months after the ISC symposium, on 14 December 1987 Tim suffered a fatal heart attack.

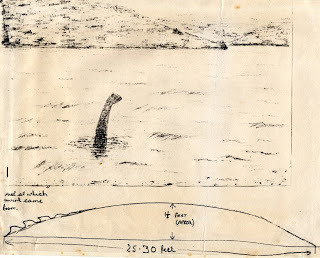

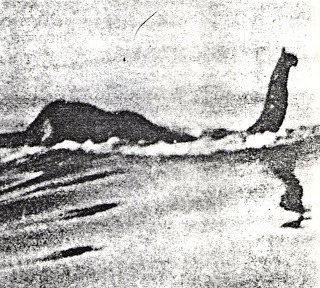

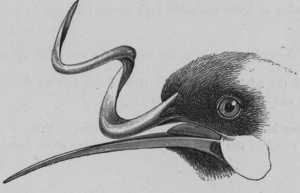

Recently, I came upon the copy of this sighting that Tim had given me all those years ago, and as I am unsure whether it was ever made public, I am now doing so, by including here on ShukerNature the sketches of what the eyewitness claimed to have seen (click image to enlarge it), together with the sparse details concerning it that I have on file, in case this may be of benefit to other Nessie researchers.

The sheet given to me on 25 July 1987 by Tim Dinsdale containing two sketches by a Nessie eyewitness

The sheet given to me on 25 July 1987 by Tim Dinsdale containing two sketches by a Nessie eyewitnessThe eyewitness observed a typical 'periscope' shape projecting up through the water surface, yielding an outline reminiscent of the object in the controversial Surgeon's Photo. He/she also saw a very long hump visible above the water surface, approximately 25-30 ft in length and approximately 1.5 ft high, with what looked like distinct backward-pointing serrations running along the posterior portion of its upper surface.

If anyone has any further knowledge concerning this Nessie sighting, I'd be delighted to receive details here on ShukerNature.

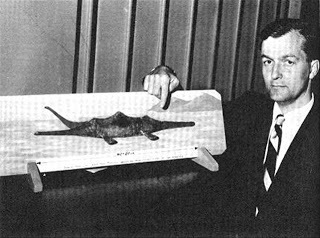

Tim Dinsdale (Tim Dinsdale)

Tim Dinsdale (Tim Dinsdale)

Published on July 29, 2013 17:35

July 26, 2013

INTRODUCING THE NANDINIA - AFRICA'S PARACHUTING (AND VERY PARADOXICAL) EX-PALM CIVET

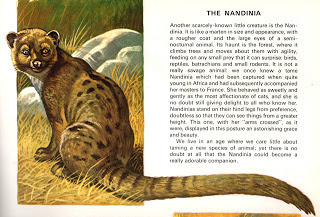

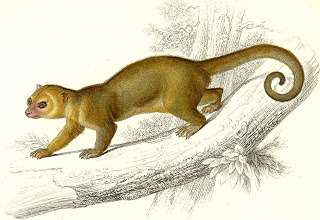

Beautiful painting of the nandinia from Robert Wolff's book Animals of Africa (© Robert Dallet)

Beautiful painting of the nandinia from Robert Wolff's book Animals of Africa (© Robert Dallet)As many of you know, I've always been interested in the more unusual, enigmatic members of the animal kingdom, those that rarely attract such widespread attention as the giant pandas and great white sharks of this world.

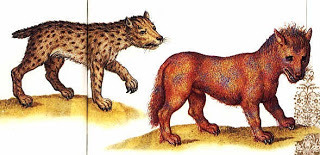

And one creature that certainly embodies 'unusual' and 'enigmatic' is the nandinia Nandinia binotata, which was formally named and described by British zoologist John Edward Gray in 1830 (and originally split into two separate species - one West African and one East African). I first learnt of this cat-sized arboreal creature's existence when, as a child, my mother bought for me a huge lavishly-illustrated book, almost as big as me (or at least it seemed to me to be at the time!), entitled Animals of Africa. Authored by Robert Wolff, it contained dozens of spectacular full-colour paintings by Robert Dallet, including one of the nandinia.

Even its name, 'nandinia', intrigued me, because it sounded so unlike any other animal name I'd ever heard, to the extent that even though I subsequently learnt that this species was also referred to as the African palm civet or two-spotted palm civet, as far as I'm concerned it has been and always will be the nandinia. It is derived, incidentally, from 'nandinie' – a local West African name for this species.

The nandinia depicted upon a Togo postage stamp issued in 1965

The nandinia depicted upon a Togo postage stamp issued in 1965Looking at its picture in Animals of Africa, which also opens this present ShukerNature blog post, the nandinia seemed to me to be a curious combination of cat and civet, with an attractive spotted coat and an exceptionally long tail, yet also indefinably different from anything else I'd ever seen. This proved to be quite a prescient assessment on my part, particularly at such a tender age, because although for many years the nandinia has been classed as a viverrid, i.e. a relative of civets and genets, in recent times it has experienced a very dramatic recategorisation.

Genetic studies have suggested that during the evolution of the carnivorans (i.e. those species belonging to the mammalian order Carnivora), the nandinia split off from the lineage leading to cats and viverrids before these latter two taxonomic families split from each other. As a result, it has been assigned to a taxonomic family of its own, Nandiniidae, of which it is the only member. As it is therefore an ex-palm civet now, this renders its alternative name of nandinia taxonomically unambiguous and thus much more desirable for use – another childhood impression of mine that has since proved prophetic.

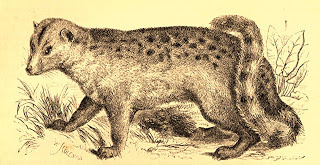

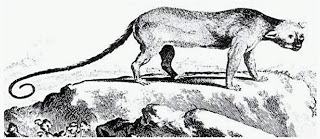

An engraving of the nandinia from Rev. J.G. Wood's three-volume animal encyclopaedia The Illustrated Natural History (1859-63)

An engraving of the nandinia from Rev. J.G. Wood's three-volume animal encyclopaedia The Illustrated Natural History (1859-63)But that was not the only surprise that the fascinating little nandinia had in store for me. While researching gliding vertebrates for a chapter in my book Extraordinary Animals Worldwide (1991), which reappeared in expanded form within its updated edition, Extraordinary Animals Revisited (2007), I accidentally discovered that the nandinia possessed a truly extraordinary but hitherto scarcely-publicised talent.

Taxiderm specimen of a nandinia in front of a taxiderm binturong at Tring Natural History Museum (Dr Karl Shuker)

Taxiderm specimen of a nandinia in front of a taxiderm binturong at Tring Natural History Museum (Dr Karl Shuker)Resembling a portly, round-headed genet with very dense, woolly brown fur dappled with small black spots, and an extremely long, barred tail, but without any form of gliding membrane or other device for achieving aeronautical success, the nandinia is the most unexpected and least known of all mammals with gliding prowess. Indeed, I learnt of its surprising capability quite by accident myself. While flipping through some African Wild Life issues from 1958 in search of an account on a totally different subject, serendipity brought to my attention a fascinating letter by G.V. Thorneycroft.

The nandinia depicted upon an Ivory Coast postage stamp issued in 1992

The nandinia depicted upon an Ivory Coast postage stamp issued in 1992In his letter, Thorneycroft recalled seeing two nandinias high up in a tree one morning on his farm at Zomba, Nyasaland (now Malawi). One became frightened by his dogs, standing at the foot of the tree barking loudly, and as a result it chose to exit the tree in a quite astonishing manner. As noted by Thorneycroft, the nandinia:

"...made a leap from a high branch and volplaned to the ground with legs and tail outstretched. It made a perfect landing on the bare ground, ran to another tree from which it again volplaned and repeated the action."

The mechanism responsible for this highly unexpected capability from as bulky and unlikely a gliding animal as the nandinia was revealed by Thorneycroft as follows:

"What struck me was the graceful way it planed or almost floated to the ground at an angle greater than half a right-angle so that it landed at a considerable distance from the tree it was in. Its tail was extended straight behind, the long hair at the base seeming to be ‘on end’ and its legs stretched out as far as possible. On each occasion it made a perfect four-point landing."

In short, the nandinia provided a surprising but nonetheless wholly corresponding verification of naturalist H.B. Cott’s classic findings with gliding frogs back in 1926 – namely, that a fully outstretched body and limbs (with or without the possession of a gliding membrane) is very important for successful aerial accomplishment.

Taxiderm nandinia at Manchester Museum (subhumanfreak at the English Language Wikipedia)

Taxiderm nandinia at Manchester Museum (subhumanfreak at the English Language Wikipedia)I have never seen any further reports of parachuting ex-palm civets, but the nandinia has a very wide distribution across tropical Africa and has even been described as probably the most common small species of forest-dwelling carnivoran there. So unless this instance of volplaning was unique behaviour exhibiting only by the single specimen observed by Thorneycroft, other occurrences must surely have been spied. Perhaps one day, therefore, some additional cases will be documented, substantiating the nandinia's claim to be the world's only species of temporarily-airborne carnivoran as opposed to merely being dismissed as a furry flight of fancy, in every sense.

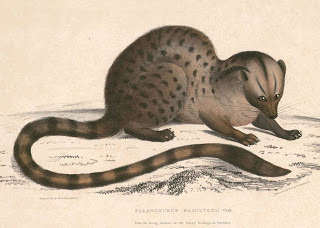

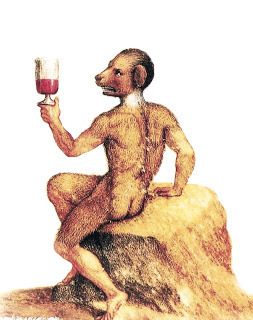

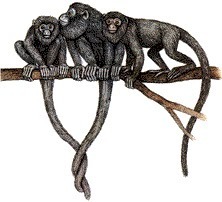

One further nandinian controversy. Four nandinia subspecies are currently recognised (namely: Nandinia binotata arborea, N. b. binotata, N. b. gerrardi, and N. b. intensa), but in earlier days a much more mysterious form, nowadays relegated to a mere synonym of Nandinia binotata, was also recognised. This was Paradoxurus hamiltonii, Hamilton's palm civet, formally named and described by John Edward Gray in 1832. The only image of P. hamiltonii that I have seen is the following one, drawn by the eminent natural history artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins in 1833-4:

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's illustration of Paradoxurus hamiltonii

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins's illustration of Paradoxurus hamiltoniiAlthough a very elegant image, it does not appear to be a particularly accurate depiction of a nandinia (which is itself surprising for an artist of Hawkins's renown), but there may be good reason for this, inasmuch as the creature so depicted might not actually be a nandinia! Why I am so curious about it is the fact that the book in which Hawkins's painting originally appeared is the second volume of a major work authored by Thomas Hardwicke, entitled Illustrations of Indian Zoology.

Yet whereas all other palm civets are indeed Asian, the nandinia has always been an oddity among such civets zoogeographically, in that it is exclusively African. So if P. hamiltonii and N. binotata are truly nothing more than two different names for one and the same species, how can we explain the presence of an illustration of P. hamiltonii in a book devoted to the mammals of India?

As far as I am aware, the aptly-named Paradoxurus hamiltonii remains a paradox today, but one that has long been forgotten. If anyone out there can shed any light on this anomaly, I'd be very happy to receive details.

The nandinia depicted upon a Liberian postage stamp issued in 1918

The nandinia depicted upon a Liberian postage stamp issued in 1918

Published on July 26, 2013 08:28

July 19, 2013

WHY BLOOD-DRAINED CARCASES ARE NOT THE WORK OF CHUPACABRAS OR OTHER SUPPOSEDLY VAMPIRIC CRYPTIDS

The carcase-desanguinating chupacabra, caught in the act? (William Rebsamen)

The carcase-desanguinating chupacabra, caught in the act? (William Rebsamen)The discovery of supposedly blood-drained animal carcases hits the cryptozoology headlines with monotonous frequency (I noticed yet another one being discussed online just a few days ago), accompanied by the usual (and sometimes decidedly unusual) media speculation as to what diabolical entity could have been responsible for such a hideous, unnatural act.

In reality, of course, no such entity – diabolical, vampiric, or otherwise – is responsible, because it is highly unlikely that such carcases really are blood-drained (variously termed desanguinated or exsanguinated). They merely look as if they are, particularly to the pathology-untrained eye, which is a very different matter altogether.

Over the years, many culprits for such unsavoury activity have been proposed – the chupacabra or goatsucker being the favourite identity if said carcases have been discovered in the New World; and various mystery carnivores, such as escapee/released big cats and even the (very) odd absconded far-from-home thylacine, if elsewhere.

Ironically, however, the true nature of these carcases has already been investigated, uncovered, and publicly exposed for all to see and read in a quite recent cryptozoology book that I heartily recommend to everyone – Ben Radford's superb Tracking the Chupacabra: The Vampire Beast in Fact, Fiction, and Folklore (University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8263-5015-2). So why such carcases should continue to perplex other researchers and the media, as indeed they still do, thoroughly baffles me.

Ben's book

Ben's bookHere's the original, unedited version of my review of Ben's book that appeared in Fortean Times (#285, March 2012):

"In modern times, very few cryptids have risen from obscurity to international celebrity with such alacrity as the chupacabra or goatsucker (indeed, I can only think of one other offhand – the Mongolian death worm). Prior to the 1990s, it was a Hispanic oddity, now it is a by-word for mysterious entities of the deliciously dark and sinister kind - emblazoned as a snarling, fiery-eyed anti-hero upon t-shirts sold in every corner of the planet, and gorily eviscerating and exsanguinating its hapless victims in saliva-dripping glee as the toothy vampiric star of countless movie and video flicks viewed worldwide.

"But what, precisely, is the chupacabra, and where did it come from? Indeed, does it even exist? Over the years since it first began hitting the media headlines in Latin America and then steadily onward and outward until its infamy became a global sensation, this monstrous marauder has been described in countless different ways by its supposed eyewitnesses – likened to just about everything, in fact, from a spiky-backed bipedal pseudo-kangaroo with wings and spinning hypnotic eyes to a hairless quadrupedal blue dog with mangy demeanour and long savage jaws. Its origin has attracted equally diverse, dramatic speculation too – a spontaneously-mutated freak of nature, an absconded scientific experiment gone wrong, even a decidedly inimical extraterrestrial visitor.

"It was high time, therefore, that this paranormal Proteus received an in-depth, critical, scientific examination, seeking both its identity and its origin, and thanks to this riveting book, that is exactly what it has received. As in his previous works, Radford has painstakingly stripped away the layers of glamour, hearsay, folklore, and media hype to reveal what he believes to be the truth behind the lurid crypto-legend, the reality at the heart of this unlikeliest of contemporary icons, and I for one consider that he has achieved his goal.

"Along the way, as with all of the most thorough investigations, there have been a number of stark, surprising revelations. Not least of these, following his forensic examination of the case in question, is Radford's comprehensive dismembering of the first major, pivotal eyewitness report (which had almost single-handedly launched the chupacabra phenomenon in fully-formed state upon an unsuspecting world).

"Also well worthy of mention here but without giving away the all-important details is his documentation of the long-awaited explanation for why supposed chupacabra victims' carcases are often described as being entirely drained of blood; as well as how another perplexing entity, the reptilian humanoid of Thetis Lake in British Columbia, Canada, was lately exposed as a hoax – a significant event, yet which had not previously received widespread coverage. Those pesky blue dogs sans hair reported from Texas and elsewhere in recent years and even represented in the flesh by one or two preserved corpses also receive Radford's full attention, revealing their identity to be intriguing but far less outstanding than media reports would suggest.

"Radford's central thesis, however, concerns the remarkable but hitherto uncommented-upon similarities between the chupacabra and the alien star of a certain science-fiction film whose release occurred just prior to the first, crucial eyewitness report of el chupa to attract major media attention. Was the latter shaped by the former? Judging from the evidence presented here by Radford, this would certainly seem to be the case, influencing everything written about and described for the chupacabra since then.

"After spending far too many years in the headlines as a bloodthirsty monster with a rapacious appetite for victims and headlines in equal measure, it looks very much as if the chupacabra has finally met its match – assassinated not with a shotgun, but instead with sterling detective work. Consequently, I feel it only fair to warn you that if you like your newly-slain goatsucker served with a generous dollop of mystery and spiced with all manner of rarefied unsubstantiated rumours, you are not going to enjoy this book. If, conversely, you prefer it plucked raw and served cold, basted only by scientific detachment and common sense, it should be a veritable feast."

The most popular representation of the chupacabra's reputed form (public domain)

The most popular representation of the chupacabra's reputed form (public domain)So, returning to the subject of desanguinated carcases, what precisely is their true explanation? As Ben revealed in his book's concluding, 35-page chapter, entitled 'The Zoology of Chupacabras and the Science of Vampires' and comprising what I consider to be the most forensic, rigorous examination of this subject ever published within the cryptozoological literature, the answer is not even remotely preternatural, but is in fact remarkably, unexpectedly mundane. Summarising his revelations, here are the most salient points:

1) Some such reports documented by the media are not first-hand but rather second-, third-, or even fourth-hand, and are thereby susceptible to distortion and fabrication of the 'Chinese whispers' and foaflore (friend-of-a-friend lore) nature.

2) Reports that are first-hand originate directly from those who have discovered such carcases, but such persons, e.g. farmers, ranchers, do not generally have medical or forensic expertise, and the carcases themselves are very rarely examined by anyone who has. So their claims that the carcases lack blood are not scientifically substantiated, and are therefore merely unsupported personal opinion, i.e. supposition.

3) If little blood is seen on or around the carcase, a layman discoverer is likely to assume that the carcase has been desanguinated, and even more likely to assume this if he should actually cut the carcase open and find little or no evidence of blood inside it. However, this apparent absence of blood is in reality no such thing. When an animal (or human) dies, rigor mortis is accompanied by livor mortis – a lesser-known process in which the carcase's blood soon begins to settle via gravity in the lower, underneath areas (which thus acquire a dark reddish-purple hue) and coagulates there, both inside vessels and in tissue surrounding vessels from which it has leaked. This only takes a few hours at most, so unless someone finding a carcase turns it over, thereby revealing the dark hue of the tissues underneath where blood has collected and coagulated (and not many people would see any reason to do so, especially with a hefty, smelly carcase like that of a dead cow or horse), the activity of livor mortis will remain hidden from view. All that will be seen is the carcase's much paler upper portion, from which blood has drained out, down into the concealed lower portions underneath.

4) Even if the carcase is turned over, if it has been lying on hard or rough ground the blood vessels in its undersurface tissues will have been compressed by the ground, thus restricting the settling of blood (i.e. livor mortis) there. So this surface will appear paler (and hence more bloodless) than would otherwise have been the case.

5) If the carcase is of an animal with dark and/or very hairy skin, livor mortis-induced discolouration will not be discerned anyway, even if the carcase is turned over, unless painstakingly examined by a medical pathologist or veterinarian via a full autopsy.

6) If a carcase is cut open and little or no blood emerges, this is due merely to the fact that it has had time to become fixed in the tissues and clotted. In short, the blood is still there, but it has simply dried up and its water content evaporated.

7) To determine scientifically the extent of blood loss, or whether there has actually been any blood loss at all, from a carcase, a full-scale formal necropsy would be required, performed by a qualified medical pathologist or veterinarian, which rarely happens with animal carcases found by farmers and ranchers on their lands, if only because of the high fee that the farmer or land-owner would be required to pay in order for such a procedure to be conducted.

8) One important indicator of significant blood loss is noticeable paleness of the internal organs, but again, unless the carcase has been professionally necropsied, this would not be readily perceived.

9) Crucially, in cases where supposedly desanguinated carcases have been examined by medical or forensic experts, they have not observed anything that they have considered to be anomalous – everything present has been in accord with their professional experience of the appearance of corpses, externally and internally. Perhaps the best-known example of this is the work of Dr David Morales, a Puerto Rican veterinarian with the Department of Agriculture. Despite having examined 300 supposedly desanguinated animal carcases that had been blamed upon the chupacabra in Puerto Rico, he found no evidence whatsoever to support such a claim. On the contrary, he found lots of blood inside the carcases, with no sign of vampirism, but plenty of signs of the animals having been attacked and killed by normal, mundane predators, such as dogs, monkeys, and birds.

In short: the blood-draining, vampiric activity of the chupacabra and other predators is a fallacy, engendered by a lack of specialised forensic, medical knowledge by those discovering and observing the carcases, as well as by exaggerated, inflamed media accounts.

Another interpretation of the chupacabra, highlighting its ferocious-looking dentition (Tim Morris)

Another interpretation of the chupacabra, highlighting its ferocious-looking dentition (Tim Morris)So the next time that you read about a mysteriously desanguinated animal carcase, remember the above checklist, and if the carcase hasn’t been subjected to a thorough autopsy by a qualified pathologist or veterinarian, the chances are that it will be its bloodless state that is non-existent, not its blood.

For full details regarding the alleged desanguination of animal carcases, please do read Ben's fascinating book, Tracking the Chupacabra – a compelling, eye-opening, and indispensable foray into the chupacabra's origin, as well as the myths, and the many fallacies surrounding this modern-day cryptozoological megastar.

Model-maker Andrew Scott's extremely formidable chupacabra (Andrew Scott)

Model-maker Andrew Scott's extremely formidable chupacabra (Andrew Scott)

Published on July 19, 2013 04:58

July 15, 2013

DOES THE LOCH NESS MONSTER HAVE A SPLIT PERSONALITY? REVEALING NESSIE'S STRANGEST IDENTITIES

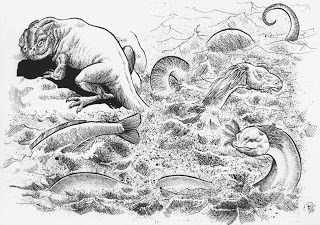

Richard Svensson's excellent demonstration of how a single lake monster can be interpreted in very different ways, based upon conflicting eyewitness accounts (Richard Svensson)

Richard Svensson's excellent demonstration of how a single lake monster can be interpreted in very different ways, based upon conflicting eyewitness accounts (Richard Svensson) Today, the classic, pre-eminent image indelibly engrained in everyone’s mind when speaking of Nessie, the Loch Ness monster (LNM), is that of a plesiosaur lookalike, complete with long slender neck and tail, small head, and four large diamond-shaped flippers.

Nessie's most popular, plesiosaurian identity (Richard Svensson)

Nessie's most popular, plesiosaurian identity (Richard Svensson) However, this was not always the case. In the past, a great diversity of alternative ideas concerning the likely appearance and identity of Scotland’s cryptozoological megastar existed. Nevertheless, with the exception of just a few (such as a sturgeon, a hypothetical long-necked seal, or various misidentified familiar animals like otters and swimming deer) that still linger tenaciously in the romantic but decidedly plesiosaurian shadow of the general public’s favourite concept for Nessie, these other options have largely been forgotten or discarded.

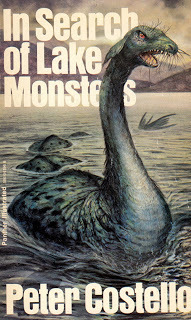

Peter Costello's book In Search of Lake Monsters espoused a hypothetical long-necked seal identity for Nessie (Peter Costello)

Peter Costello's book In Search of Lake Monsters espoused a hypothetical long-necked seal identity for Nessie (Peter Costello) Yet they included some truly extraordinary notions and fascinating sightings, which richly deserve their belated resurrection here, as we examine just a selection of those most curious of LNM identities - identities that may have been, might still be, and surely could never, ever be...could they?

OTTERLY MYSTERIOUS

The most familiar cryptozoological identity proffering a furry or hairy mammalian Nessie as opposed to a sleek scaled or scaleless reptilian counterpart is a giant long-necked seal - of the kind first postulated during the 1960s by pioneering cryptozoologist Dr Bernard Heuvelmans for his ‘longneck’ category of sea serpent, and later adopted for lake monsters too by Peter Costello. This identity still receives some attention today. In contrast, a second mammalian cryptid contender has long been consigned to obscurity – a giant long-necked otter.

Its principal proponent was British zoologist Dr Maurice Burton. Although dismissing most Nessie reports as floating algal mats or misidentified known animals, in his book The Elusive Monster (1961) he considered it possible that a small number of reports genuinely featured an undiscovered lutrine form. And perhaps his most memorable claim was that if a long-necked giant otter did exist, it should not be looked for in the loch but on land instead: “…in the marshes or on islands (e.g. Cherry Island), up the burns and rivers or along the shores of the loch, although it may also be seen occasionally in the water”.

An otter impersonating Nessie (Dr Karl Shuker)

An otter impersonating Nessie (Dr Karl Shuker) How ironic it would be if generations of Nessie seekers have been looking for the LNM in entirely the wrong habitat! Intriguingly, an unknown long-necked giant otter-like beast has long been reported from western Ireland, where it is termed the dobhar-chú or master otter.

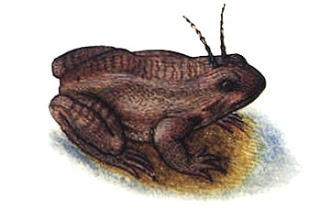

A FROG AS BIG AS A GOAT?

What may well be a unique sighting of Nessie, made as it was underwater, took place one day in 1880, when diver Duncan MacDonald was lowered into Loch Ness at Johnnies Point, close to the loch’s Fort Augustus entrance to the Caledonian Canal. Not long afterwards, however, he resurfaced, gesticulating wildly to his colleagues to pull him out, and in such a terror-stricken state that it took several days before he was finally able to explain why he had been so scared.

He revealed that while he had been examining at a depth of around 10 m the keel of the sunken ship that he had been sent down to investigate, he had been horrified to see a very large and truly frightening creature lying on a shelf of rock that was supporting the ship. According to his description, the creature resembled a huge frog, at least as big as a goat, and it was staring directly at him! Not surprisingly, MacDonald refused outright to enter Loch Ness ever again.

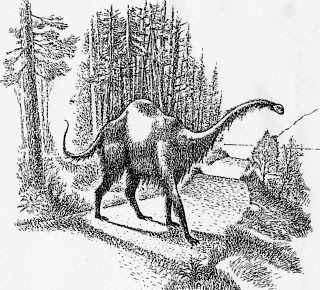

Could Nessie be a gigantic salamander?

Could Nessie be a gigantic salamander? The concept of Nessie being a gigantic amphibian was revisited most notably almost a century later. This was when, in 1976, veteran cryptozoologist Dr Roy P. Mackal, a Chicago University biochemist by profession, published what remains the most scientific, rigorously objective study of the LNM in book form.

Entitled The Monsters of Loch Ness, in it Mackal meticulously examined every reasonable zoological identity, and concluded that the most plausible Nessie candidate was a giant newt- or salamander-like amphibian, which in his view would account for 88% of the LNM characteristics on file (as opposed to 56% for a species of seal, 47% for a sea-cow, 69% for a plesiosaur, 78% for a species of eel, and 59% for a mollusc). Yet despite the convincing and thorough nature of his researches, Mackal’s mega-newt theory failed to break the plesiosaur’s limpet-like grip upon the imagination of Nessie seekers and the media at large.

MIGHTY MANTAS AND EUNUCH EELS

Two of the fishiest Nessie identities – zoologically – feature a couple of very different contenders of the piscean persuasion. Cryptozoologists Paul and Lena Bottriell are most famous for their king cheetah researches, but in 1988 they turned their attention briefly to Nessie, and in an exclusive High Wycombe Star newspaper interview published on 28 October they offered a new identity for this cryptid.

Based on personal sightings of a school of rays seen while snorkelling off Queensland, Australia, Paul postulated that the LNM may be a very large ray, sporting a series of dorsal fins along its lengthy slender tail (as species such as the electric ray possess), thereby producing the characteristic Nessie humps if protruding through the water surface. He also proposed that its elongate tail could create the familiar ‘head and neck’ Nessie image if lifted up out of the water (rays do lift their tails in warning displays). Although an ingenious, original idea, the notion of a ray’s tail explaining Nessie’s head and neck clashes with LNM eyewitness reports that have claimed the head and neck to be unquestionably sentient, actively observing while above the water surface.

An underwater moray eel impersonating Nessie's famous 'periscope' head and neck pose at Sea World in San Diego, California, as witnessed by me during a visit there in 2004 (Dr Karl Shuker)

An underwater moray eel impersonating Nessie's famous 'periscope' head and neck pose at Sea World in San Diego, California, as witnessed by me during a visit there in 2004 (Dr Karl Shuker)Equally ingenious is the most recent non-plesiosaur identity of note to be aired for Nessie. Expanding upon the longstanding belief of various investigators that extra-large eels may be responsible for at least some LNM reports, in 2003 Richard Freeman of the CFZ suggested that Nessie may well be a gigantic, sterile or eunuch specimen of the common eel Anguilla anguilla – one that did not swim out to sea and spawn but instead stayed in the loch, grew exceptionally long (8-9 m), lived to a much greater age than normal, and was rendered sterile by some presently undetermined factor present in this and other deep, cold, northern lakes.

I would not be at all surprised to learn that extra-large eels do exist here (indeed, such fishes have been reported by divers in the loch), and they could certainly explain some Nessie sightings of the ‘humps above the water’ variety. However, I cannot reconcile any kind of eel with the oft-reported vertical head-and-neck category of LNM sightings, nor with the land sightings that have described a clearly visible four-limbed, long-necked animal.

Also, in response to this ‘eunuch eel’ theory, Dr Scott McNaught, Professor of Lake Biology at Central Michigan University, has stated that even if such eels did arise, they would tend to grow thicker rather than longer. Nevertheless, giant eels remain a distinct possibility in relation to some of the world’s more serpentiform lake monsters on record.

IS THE ELEPHANT SQUID A WIZARD IDEA?

Tony ‘Doc’ Shiels is familiar in the fortean community as a wizard, surrealist artist, showman, and cryptozoological enthusiast, with a particular interest in water monsters, and he claims to have photographed several, including the LNM. Moreover, in relation to this latter cryptid he has proposed a highly original zoological identity – an as-yet-hypothetical, extremely modified species of enormous squid, which in 1984 he dubbed the elephant squid Dinoteuthis proboscideus. This was because its most distinctive feature is a long flexible prey-capturing structure resembling an elephant’s trunk, which, held above the water surface, would account for Nessie’s ‘head and long neck’ image. Shiels also postulated the presence of inflatable dorsal airsacs for buoyancy purposes, which would explain the many LNM sightings of humps breaking through the loch’s water surface.

Doc Shiels's sketch of his hypothetical elephant squid (Tony 'Doc' Shiels)

Doc Shiels's sketch of his hypothetical elephant squid (Tony 'Doc' Shiels) Naturally, however, so dramatically different a species of squid as this would require a very considerable evolutionary deviation from the more generalised squid blueprint, and not just morphologically. Currently, there is not a single scientifically-confirmed species of freshwater squid on record – every squid presently known to exist today is exclusively marine. So for Shiels’s elephant squid to be a reality, it would need to exhibit profound osmoregulatory adaptations to a freshwater lifestyle.

"I’VE NEVER SEEN ANYTHING LIKE IT IN MY LIFE!"

The above words, as sung by circus owner Albert Blossom in the classic 1960s Warner Brothers film musical ‘Doctor Dolittle’ upon first seeing the incredible two-headed pushmi-pullyu, came unbidden, but very aptly, into my head when, after first reading the thoroughly astonishing, one-of-a-kind Nessie sighting claimed by L. McP. Fordyce, I looked at the accompanying artistic reconstruction based upon his own sketch of what he allegedly saw. According to his report (Scots Magazine, June 1990), his extraordinary encounter occurred in 1932 (just a year before Nessie fever filled the headlines worldwide and the term ‘Loch Ness monster’ was coined).

Driving along a woodland-surrounded stretch of road leading away from the lochside and towards Fort William, he and his fiancée were amazed to see a huge creature come out of the woods on their left and step over the road about 150 m ahead towards the loch. Fordyce described it as having “the gait of an elephant, but looked like a cross between a very large horse and a camel, with a hump on its back and a small head on a long neck…From the rear it looked grey and shaggy. Its long, thin neck gave it the appearance of an elephant with its trunk raised”. He stopped the car, and followed this bizarre animal for a short distance on foot before deciding that it may be safer to abandon his pursuit and go back to his car.

An artistic representation of Fordyce's extraordinary 'giraffe-camel Nessie' (Scots Magazine, June 1990)

An artistic representation of Fordyce's extraordinary 'giraffe-camel Nessie' (Scots Magazine, June 1990)So unlike the typical LNM is this truly weird entity, depicted in Fordyce’s account with long slender legs far removed from the flippers more commonly associated with Nessie, that I swiftly checked that this was not the April issue of the magazine in question, but the article ended with an even stranger note. Fordyce revealed that, as stated in Ronald Binns’s book, The Loch Ness Mystery Solved (1983), in 1771 a Patrick Rose had learnt of a monster seen in Loch Ness that was said to resemble a cross between a horse and a camel. However, this no doubt referred to Nessie’s head and neck (rather than to the entire animal), which have indeed been likened to those of a horse on many occasions. So too have those of water monsters elsewhere, including North America’s Caddy, a sea monster whose head has been compared with that of a camel as well.

A NOT SO MONSTROUS TULLIMONSTRUM?

One of the most bewildering Nessie sightings was that of Mr and Mrs George Spicer. Driving along the road between Dores and Foyers on 22 July 1933, they spied a very large entity emerging from the bushes onto the road ahead. They described it as “an abomination…a loathsome sight”, with a long neck, but no apparent limbs, later likened to a massive slug or worm-like beast in some accounts, which lurched rapidly across the road and into the bracken separating it from the lochside.

One Nessie investigator impressed with the prospect of a worm as a suitable explanation was F.W. Holiday. In his book The Great Orm of Loch Ness (1969), he nominated a particularly unusual animal as his favoured Nessie. Namely, a hypothetical giant modern-day descendant of a bizarre prehistoric worm called Tullimonstrum gregarium, or the Tully monster (after Francis J. Tully, who first brought this fossil species to scientific attention in 1958).

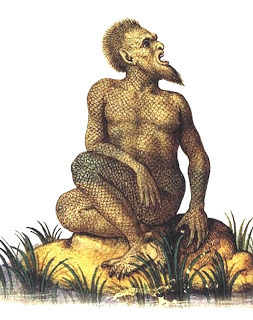

A representation of Tullimonstrum gregarium (Apokryltaros at en.wikipedia)

A representation of Tullimonstrum gregarium (Apokryltaros at en.wikipedia) What intrigued Holiday about this animal was its unexpectedly Nessie-esque morphology. Unlike more conservative vermiform creatures, Tullimonstrum sported a pair of small anterior flipper-like appendages (though these may have been eye-stalks), a sizeable three-part diamond fin encircling the rear portion of its body, and a very long, slender jaw-containing proboscis superficially resembling an elongate LNM-type neck and head. However, unlike Nessie, which is often claimed to measure around 10 m long, Tullimonstrum was only a few cm long, is known only from Illinois, and became extinct 300 million years ago – no doubt explaining why this identity never captured the public imagination.

THE ELEPHANT OF SURPRISE?

As revealed here, several Nessie identities contain more than an element of surprise, but none more so than when the element is an elephant. After all, whatever Nessie may be, she is certainly no pachyderm...is she? Remarkably, in a New Scientist article of 2 August 1979, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History director Dr Dennis Power and Illinois University geography research associate Dr Donald Johnson cited similarities between the controversial Surgeon’s head-and-neck Nessie photograph of 1934 and a frame from a film taken on 15 July 1960 by Admiral R. Kadirgamar of an elephant and her calf swimming from Ostenburg Ridge to Sober Island in Trincomalee Harbour, Sri Lanka, and speculated that perhaps travelling circuses have occasionally released their elephants into Loch Ness to bathe, which might then explain the Surgeon’s photo (an image, incidentally, that in years to come would be famously condemned – but never confirmed!! – as a hoax).

The above-documented frame from Admiral R. Kadirgamar's film of an elephant and her calf swimming off the coast of Sri Lanka in July 1960, yielding a surprisingly Nessie-like outline (Admiral R. Kadirgamar)

The above-documented frame from Admiral R. Kadirgamar's film of an elephant and her calf swimming off the coast of Sri Lanka in July 1960, yielding a surprisingly Nessie-like outline (Admiral R. Kadirgamar)And as proof that history, even of the strangest variety, does repeat itself, in 2006 the startling elephant-Nessie scenario unexpectedly returned to the headlines when the very same notion was offered up by palaeontological curator Dr Neil Clark from Glasgow University’s Hunterian Museum. An elephant in the loch’s waters, or a camel in its woods? Bring back Tullimonstrum – all is forgiven!

MONSTERS, MONSTERS, EVERYWHERE!

Unlike Nessie’s many investigators, Robert Lawson Cassie was one seeker of Scottish Highland water monsters who never had problems finding them. On the contrary, ever since he began his observations, in June 1934, everywhere he looked near his home village of Achanalt he saw monsters! As revealed in this 77-year-old author’s mesmerising, self-published 2-volume book, The Monsters of Achanalt (1935-36), the local rivers and lochs were - at least as far as he could see – quite literally bursting at the seams with monstrous reptiles, and of gargantuan dimensions.

Indeed, one such denizen of Loch Achanalt that he dubbed Gabriel was estimated by him to measure approximately 300 m long, which meant it was only 50 m shorter than the loch itself! Moreover, it was, he claimed, just one of countless other, smaller monsters inhabiting this modestly-sized expanse of freshwater, with plenty more in Lochs Cronn, Culon, Garve, and Rosque - even though most of these are no deeper than 10 m.

Loch Achanalt (Dave Conner/Flickr/Wikipedia)

Loch Achanalt (Dave Conner/Flickr/Wikipedia) Nor were Cassie’s sightings confined to the aquatic domain. As soon as he started looking for monsters on land, where he was convinced that they must breed, he was equally successful - even reporting a sighting of two giant reptilian necks outlined against the snowy face close to the summit of Morusig! Not surprisingly, Cassie’s absurd observations and books rarely rate a mention in other cryptozoological publications, and are generally dismissed either as the outpourings of an extreme eccentric or as a tongue-in-cheek hoax.

Why, with such a range of other candidates to consider, does the plesiosaur identity steadfastly remain so popular? It is true that, on the one hand, some of the land sightings of Nessie have described an undeniably plesiosaurianesque entity. On the other hand, however, all manner of scientific objections to the likelihood of a modern-day representative of this officially long-demised lineage of prehistoric aquatic reptile persisting in Loch Ness have been aired over the years. My own belief is that there is no single answer to the mystery of Nessie – instead, I consider it most likely that what we refer to as the LNM is in reality a composite of several different phenomena.

Be that as it may, what seems to raise the plesiosaur’s profile far above that of any would-be pretender to the Nessie throne is that the notion of some lingering race of antediluvian monster - an erstwhile contemporary of the mighty dinosaurs, no less - lurking reclusively beneath the loch’s dark, mysterious waters conjures forth an incomparably romantic and, equally, chilling scenario that no over-sized newt, emasculated eel, trunk-erecting squid, vermiform wannabe, or even the (very) odd giraffe-necked water camel could ever hope to compete with!

A truly wonderful Nessie-inspired cartoon by Keith Waite that originally appeared in London's Sunday Mirror newspaper on 2 April 1972 but which surely cried out for inclusion in any article dealing with the many different faces of Nessie! (Keith Waite/Sunday Mirror)

A truly wonderful Nessie-inspired cartoon by Keith Waite that originally appeared in London's Sunday Mirror newspaper on 2 April 1972 but which surely cried out for inclusion in any article dealing with the many different faces of Nessie! (Keith Waite/Sunday Mirror)

Published on July 15, 2013 16:26

July 4, 2013

WELCOME TO MIRABILIS - A SNEAK PREVIEW OF MY LATEST BOOK, PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER 2013

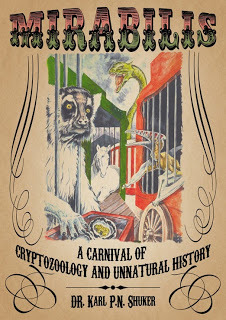

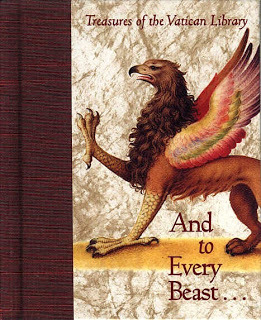

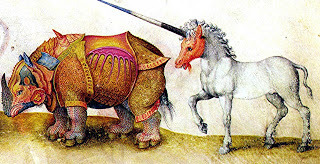

The spectacular artwork on the front cover of Mirabilis is by the wonderfully-talented artist Anthony Wallis - thanks, Ant!

The spectacular artwork on the front cover of Mirabilis is by the wonderfully-talented artist Anthony Wallis - thanks, Ant!Just two months to go before my latest, 19th book is published - Mirabilis: A Carnival of Cryptozoology and Unnatural History. So here's a sneak preview of what it has in store for you....

Welcome to a carnival unlike anything that you have ever read about, visited, or even imagined before. Here, before your very eyes, you will encounter bizarre, anomalous creatures of every conceivable (and inconceivable!) kind – a veritable menagerie of cryptozoological mysteries to dazzle and delight, tantalise and terrify. For this is Mirabilis – a realm of marvels, wonders, miracles...and monsters!

Peer through the shadows and see what you may. Was that scuttling horror a spider the size of a puppy, did that fallen tree trunk suddenly sprout a pair of alligator jaws, was that a living toad that leapt out of that split-asunder block of stone, and did those flowers abruptly put forth wings and fly away as tiny birds?

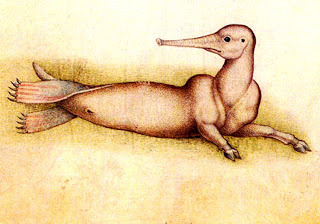

Behold Trunko, the hairy marine elephant-bear that supposedly battled whales off the coast of South Africa almost a century ago. Look around in every direction and witness the very last giant lemurs brought to you from the rainforests of Madagascar, the very same unicorn that was once encountered by Julius Caesar, dinosaur-sized crocodiles from the swamps of the Congo, the elephantine harpoon-tusked sukotyro of Sumatra, gargantuan prehistoric beavers resurrected in modern-day North America, illusive Germanic horned hares and elusive Liberian micro-squirrels, a giant sea snail with antlers and paws from the Sarmatian Sea and a veritable whale-fish from a forgotten Swedish lake, a vanished striped mystery steed from Iberia, enormous toothless freshwater sharks from South America, flying turtles from China and a hippoturtleox from Tibet, sea dragons and pseudo-pterodactyls, and the world's only known tusked megalopedus - plus much, much more!

Let us not tarry even a moment longer. The miracles and marvels of Mirabilis await you impatiently inside, to scintillate, spellbind, and stultify your senses. So I bid you welcome, and pray that your visit to my carnival of cryptozoology and unnatural history will be entertaining...and not too perilous!

Mirabilis is published by Anomalist Books , and should be available in e-book form as well as traditional hard-copy paperback. Prices have yet to be finalised, but keep checking back here, on the Anomalist Books website, and on Amazon for pre-ordering details.

Mirabilis - the Cirque du Soleil of cryptozoology books??

Representation of Julius Caesar's unique unicorn (Markus Bühler)

Representation of Julius Caesar's unique unicorn (Markus Bühler)

Published on July 04, 2013 07:37

June 28, 2013

MY TOP TEN NEW AND REDISCOVERED ANIMALS OF MODERN TIMES

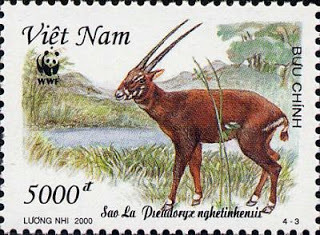

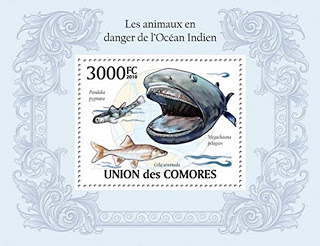

A young saola, depicted upon a postage stamp issued by Vietnam in 2000

A young saola, depicted upon a postage stamp issued by Vietnam in 2000It is widely known that many remarkable species of animal have become extinct or at least highly endangered in modern times. However, it is far less well known that during this same time period, a startling number of equally spectacular species have been newly discovered (having been previously unknown to science) or rediscovered (after having been written off as extinct by science). Here, then, in no particular order, is my personal Top Ten of our planet's most extraordinary and scientifically significant zoological arrivals and revivals of modern times – with my interest in cryptozoological philately providing the illustrations.

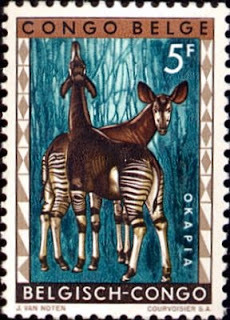

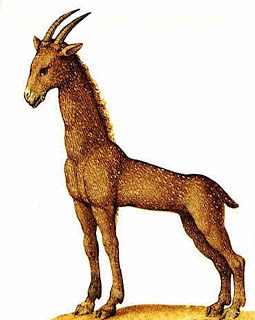

THE OKAPI

Discovered in 1901, the okapi remains one of the most famous and dramatic new animals to have been unveiled for over a century. Back in 1890, explorer Henry Morton Stanley noted that the Wambutti pygmies inhabiting the Ituri Forest in what is nowadays the Democratic Republic of Congo had informed him that they sometimes trapped in concealed pits a kind of 'forest donkey' known to them as the atti. When Ugandan governor Sir Harry Johnston learnt of this, he made enquiries, as a result of which some soldiers from the Congo gave him two strips of vividly striped skin from one such animal. Convinced that this elusive beast, which he learnt was actually known locally as the okapi, was an unknown forest zebra, he sent the skin strips to London's Zoological Society, where they could not be identified with any known species.

In 1901, Sir Harry succeeded in obtaining a complete okapi skin as well as two skulls, and he sent these to London's Natural History Museum, to await the experts' verdict on the okapi's zoological identity. To everyone's amazement, it proved not to be a zebra at all, but something far more extraordinary. It was a giraffe, but no ordinary one. A totally separate species from the familiar long-necked spotted giraffe of the savannahs, the okapi was a relatively short-necked, stripe-rumped species with purple-brown skin, which was adapted for an exclusively forest-dwelling lifestyle. Although similar species were known from the fossil record, it had been assumed that all of these short-necked giraffes had died out millions of years ago, but the okapi's sensational discovery emphatically disproved this. In honour of Sir Harry's successful investigations, the okapi was formally named Okapia johnstoni.

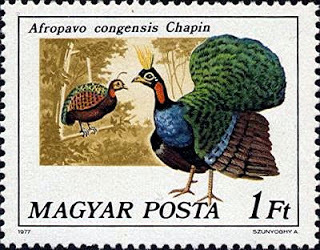

THE CONGO PEACOCK

The okapi wasn't the only modern-day zoological surprise revealed in the Ituri Forest. During a scientific expedition there in 1913, American Museum of Natural History ornithologist Dr James Chapin spied a native head-dress containing an unusual feather that he had never seen before. He was so intrigued that he purchased the head-dress, but after a long, vain attempt to identify the feather's mysterious species he finally placed this perplexing plume in his desk, but he never forgot it.

In 1936, during a visit to the Congo Museum at Tervueren, Belgium, Chapin spotted a pair of shabby, forgotten taxiderm birds on top of a dusty cabinet separated from the museum's principal collection - and was amazed but delighted to see that the female bird had wing quills identical to his mystifying feather. Investigating this fortuitous discovery, Chapin learnt that these birds' species inhabited the Ituri Forest, where it was known as the mbulu.

By mid-1937, he had acquired several fresh specimens of the mbulu for detailed examination, which revealed it to be a species of peacock hitherto unknown to science, and the only one native to Africa. Very primitive in appearance, it lacked the exquisite fan-like train typifying the familiar Asian peacocks. Chapin dubbed this remarkable new bird Afropavo congensis, the Congo peacock, and it is still deemed to be the most significant ornithological discovery of the past 100 years.

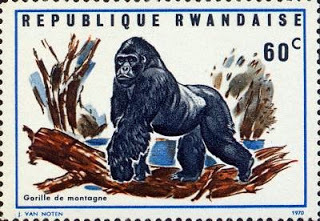

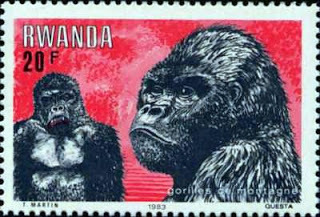

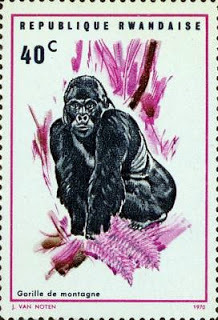

THE MOUNTAIN GORILLA

As far back as 1860, the explorer John Speke had collected native reports of a huge, man-eating hairy ogre that inhabited the Virunga Volcano range of mountains constituting the physical border between the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Uganda, but science dismissed such stories as mere superstition and folktales.

In 1902, however, a Belgian army officer called Captain Robert 'Oscar' von Beringe actually shot two of these hairy 'ogres', and sent them to Europe, where they were found to constitute a totally new form of gorilla - quite different from lowland versions, with a broader chest, longer, darker fur, and longer jaws with larger teeth. The mountain gorilla had finally been discovered, and is referred to scientifically as Gorilla beringei beringei.

Happily, we now know that far from being a man-eating ogre, it is actually one of the shyest and most gentle of creatures - as revealed via the studies of Dr George Schaller, and those of the late Dian Fossey (whose life was the subject of the film Gorillas in the Mist).

THE COELACANTH

Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, curator of the small East London Museum in South Africa, often visited the nearby docks in search of unusual fishes to preserve as specimens for exhibition in the museum, but during a visit in December 1938 she spotted a fish unlike anything that she had ever seen before. Approximately 1.5 m long and steely-blue in colour, what made it so distinctive were its fins, as both the pectoral and the pelvic fins looked just like stubby legs, and, uniquely among all living fishes, its tail fin possessed three lobes instead of just two. Totally baffled by her strange unidentified find, Courtenay-Latimer arranged for it to be transported to the museum and preserved.

She also wrote a letter (containing a sketch of the fish) to a colleague who had assisted her in identifying fishes in the past – world-acclaimed South African ichthyologist Prof. J.L.B. Smith. When he opened it, he was astonished to see that her sketch closely resembled a coelacanth, belonging to an ancient lineage of fishes hitherto believed to have died out over 64 million years ago alongside the dinosaurs! He lost no time in visiting the East London Museum to see this amazing fish himself, and was able to confirm straight away that it was indeed a genuine, modern-day species of coelacanth.

When Prof. Smith formally documented this sensational zoological find, he named its species Latimeria chalumnae, in honour of its discoverer. After a gap of almost 14 years, more coelacanth specimens belonging to this same 'living fossil' species were found, in the waters around the Comoro Islands. And in 1997, a separate, second species of modern-day coelacanth was discovered in the seas around the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. It was christened Latimeria menadoensis, and possessed brown scales instead of blue ones.

THE SAOLA

The most spectacular new species of large mammal to have been discovered in recent times is undoubtedly the saola or Vu Quang ox. While conducting field research in an unexplored forest-covered mountainous region of northern Vietnam called Vu Quang during 1992, American conservationist Dr John MacKinnon observed that various native hunters exhibited as trophies in their homes some very long, pointed horns that were unlike those of any species native to anywhere in Asia. Indeed, the only horns that they resembled were those of certain African and Arabian antelopes known as oryxes. When he asked the hunters what animal these mystifying horns came from, he was told that it was a very shy, rarely-seen ox-like creature referred to by them as the saola.

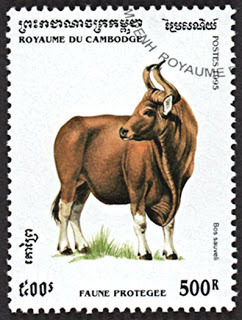

Further enquiries resulted in the procurement of a near-complete dead specimen, revealing the saola to be a dramatically new species that combined a bovine body with the long horns and slender legs of an antelope. It was formally named Pseudoryx nghetinhensis, emphasising its horns' deceptive similarity to an oryx's, but in reality the saola has no close relatives among other species. The size of a buffalo – the saola is the largest new mammal to have been discovered since the kouprey or Cambodian wild ox Bos sauveli in 1937.

This makes the saola's very belated scientific discovery even more remarkable. A few living specimens have subsequently been observed in the wild, and a few even captured and studied alive for short periods, but it remains little-known and very scarce.

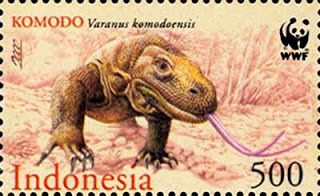

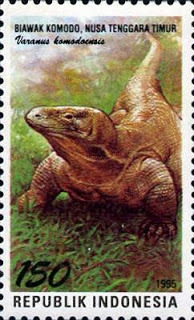

THE KOMODO DRAGON

Komodo is a small island in Indonesia's Lesser Sundas chain, southeast of Java, and was once used as a convict island for prisoners. Pearl fishermen visiting Komodo were told by the prisoners that this island harboured a huge, ferocious species of land crocodile. Scientists, however, dismissed such claims as fantasy, until, in 1910, Major P.A. Ouwens, director of Java’s Botanical Gardens at Buitenzorg, near Batavia (now Jakarta), became sufficiently intrigued by them to send a local amateur naturalist to Komodo in search of the truth. When he returned, he confirmed that such creatures really did exist, but they were not crocodiles. Instead, they constituted a giant species of monitor lizard, and as proof he had brought back the skin of one.

In 1912, this spectacular new species was formally described by Ouwens, who named it Varanus komodoensis, the Komodo dragon. It can grow up to 3 m long and weigh up to 70 kg, making it the world's largest lizard. Komodo dragons will kill and devour anything that they can catch – including other Komodo dragons, and humans!

THE CHACOAN PECCARY

Until the mid-1970s, only two species of pig-like peccary were known to science, but during a visit in 1974 to the semi-arid Gran Chaco region of South America, overlapping Paraguay, Argentina, and Bolivia, American zoologist Dr Ralph Wetzel obtained skulls and other physical evidence testifying to the existence of a third, somewhat bigger species. What made this discovery even more significant, however, is that when these remains were studied, zoologists realised that their species was already known to science – but only as a fossil form hitherto assumed to have died out at the end of the Ice Ages 10,000 years ago. In reality, however, Wetzel's discovery showed that it had not died out at all, but its modern-day survival had not previously been realised by scientists, even though it was a familiar creature to the Chaco inhabitants. This resurrected species is nowadays known as the Chacoan peccary Catagonus wagneri.

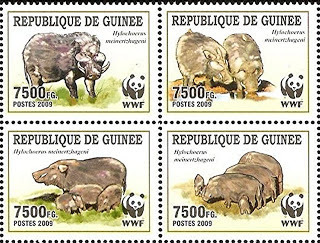

In 2003, an even bigger peccary – the world's largest species – was discovered in Brazil; and in 2007, it was formally recognised and named Pecari maximus, the giant peccary. And back in 1904, the world's largest wild species of true pig, the aptly-named giant forest hog Hylochoerus meinertzhageni, was unveiled in Kenya.

THE MEGAMOUTH SHARK

On 15 November 1976, the crew of an American research vessel situated in the waters off the Hawaiian island of Oahu hauled up one of its anchors at the end of the day – and were astonished to discover that it had been partly swallowed by a huge and wholly-unfamiliar shark, which was hauled up with it as the anchor was wedged inside its exceptionally large mouth. The shark had choked to death, so its bulky 4.25-m-long body was taken to Hawaii's Kaneohe Laboratory for preservation. Following a very extensive study, in 1981 it was proclaimed as an entirely new species of shark, radically dissimilar from any previously recorded.

Formally named the megamouth shark Megachasma pelagios, it was so dramatically different, in fact, that it required the creation of a wholly new zoological family in order to accommodate it within the shark classification system. Since then, a sizeable number of additional specimens have been recorded in seas all around the world, making the late scientific discovery of such a large and distinctive species of fish all the more extraordinary, and confirming that the vast oceans undoubtedly hold many more zoological surprises in store.

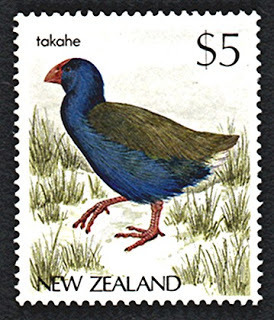

THE TAKAHE

New Zealand is home to many species of unusual bird found nowhere else in the world, but one of the most beautiful, and elusive, is a multicoloured, flightless relative of coots and moorhens known as the takahe Porphyrio mantelli. Almost as big as a turkey and surviving only on the South Island, it was originally discovered in 1849, but was only rarely seen, and many years would often pass between successive sightings. After a sighting in 1898, however, no further confirmed reports of the takahe emerged for several decades, and zoologists eventually deemed that this time it must surely be extinct.

In November 1948, however, after learning from local Maoris of a mysterious lake not known to Europeans but around whose shores they claimed takahes could still be found, New Zealand physician Dr Geoffrey Orbell organised an expedition to this lake. On 20 November, while the team was searching there, and without any prior warning, just ahead of them a takahe unexpectedly stepped into view - and into history - as the first living specimen recorded for 50 years! Its species' rediscovery is one of the most significant in modern times, and the takahe is now fully protected.

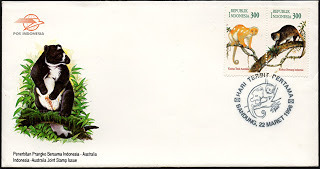

THE DINGISO

In 1994, while visiting the hitherto scarcely-explored Sudirman mountains of Irian Jaya, the western, Indonesian half of New Guinea, Australian zoologist Dr Tim Flannery encountered a completely unfamiliar yet extremely distinctive species of tree kangaroo, whose eyecatching black and white fur made it look more like a panda! Moreover, in spite of its zoological status, this particular tree kangaroo preferred to spend much of its time on the ground, and was relatively tame, whistling loudly at anyone approaching it. It transpired that the native Moni tribe sharing its forest habitat revere this species as their own ancestor, and thus refrain from hunting it, explaining why it was unafraid of humans.

Known to them as the dingiso, it was totally new to science, and when officially documented and described, it was christened Dendrolagus mbaiso. This delightful panda-lookalike is the most dramatic new species of mammal to have been discovered in Australasia for many years.

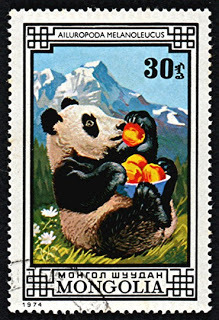

And speaking of pandas: the giant panda Ailuropoda melanoleuca was itself only rediscovered in 1928 after having been written off as extinct for several decades after its original discovery by western science in 1868.

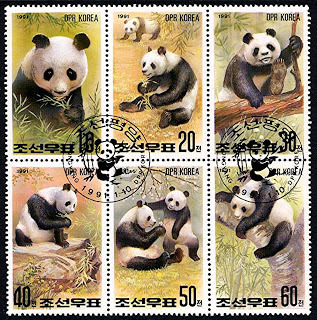

Just over a century ago, zoologists were confidently predicting that all of the world's major animal forms had been found and catalogued. How wrong they were. Even today, very notable new species of animal are still being discovered, and species long believed extinct are still being rediscovered, as documented in my recent book The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals (Coachwhip Books: Landisville, 2012). This is why the conservation of existing wildlife habitats worldwide remains so imperative, in order to preserve biodiversity and avoid the horrifying prospect of remarkable animal species becoming extinct without their existence ever having been discovered. What a terrible tragedy that would be.

My sincere thanks to Pib Burns for kindly permitting me to include in my article a selection of postage stamp illustrations from his excellent cryptozoological philately site - please click here to visit it and see more postage stamps depicting new, rediscovered, and still-undiscovered animals.

And for lots more information on every major new and rediscovered animal from 1900 to the present day, check out my recent book, The Encyclopaedia of New and Rediscovered Animals - the definitive book on all such creatures.

Published on June 28, 2013 06:58

June 26, 2013

REMEMBERING THE HUIA – HISTORY AND MYSTERIES OF THE BIRD WITH TWO BEAKS

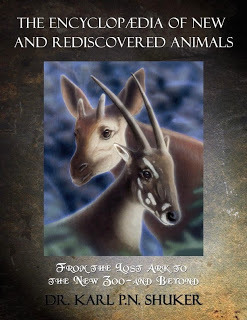

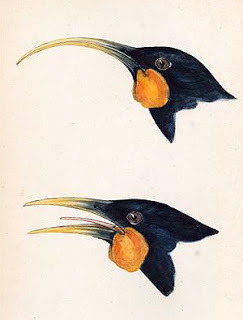

The most famous huia painting, prepared by celebrated bird artist Johannes G. Keulemans for the 2nd edition (1888) of Sir Walter Buller's A History of the Birds of New Zealand

The most famous huia painting, prepared by celebrated bird artist Johannes G. Keulemans for the 2nd edition (1888) of Sir Walter Buller's A History of the Birds of New ZealandDeriving its name from its distinctive melodious call, the huia Heteralocha acutirostris was a member of a small family of birds found only in New Zealand and referred to as wattlebirds. A crow-sized species whose glossy black plumage disclosed a deep green sheen when viewed at certain angles in sunlight, it was instantly characterized by its pair of bright orange facial wattles, its elegant tail plumes with broad tips decorated by a wide band of sparkling white (tinged with rufous in young birds), and - above all else - by the truly exceptional, extraordinary nature of its ivory-coloured beak, for unlike virtually all other birds (see below) the huia had not one beak but two.

Female (top) and male (bottom) huia heads, by John Gould, 1837-1838

Female (top) and male (bottom) huia heads, by John Gould, 1837-1838Indeed, when first scientifically described in 1836, by eminent ornithologist and bird painter John Gould, the male and female huias appeared so dissimilar in form that he mistakenly named and designated them as two separate species – Neomorpha crassirostris (the male huia) and Neomorpha acutirostris (the female huia)

A pair of huias – the male with a straight beak, the female with a curved beak; colour plate from 1860, based upon John Gould's original painting of 1848

A pair of huias – the male with a straight beak, the female with a curved beak; colour plate from 1860, based upon John Gould's original painting of 1848This is not as surprising as it might otherwise seem, because whereas the male huia’s beak was short and straight, used for chiselling out grubs (especially those of Prionoplus reticularis, a longhorn beetle commonly called the huhu) from decayed wood as a woodpecker does, the female’s was long and curved gracefully downward, enabling her to secure grubs from deep woody crevices that her mate’s short beak could not reach.

Huhu grubs (Charlotte Simmonds/Wikipedia)

Huhu grubs (Charlotte Simmonds/Wikipedia)Many animal species exhibit some degree of sexual dimorphism, but in birds this usually involves plumage or body size. The huia’s drastic departure from that tradition, by possessing a sexually dimorphic beak, established it as a species of immense scientific worth, which made its extinction all the more tragic. (Recently, it has been shown that a second vanished species of bird, the Réunion crested starling Fregilupus varius, extinct since 1837, also sported a sexually dimorphic beak, but not to such a pronounced degree as in the huia.)

Keulemans's painting of the Réunion crested starling

Keulemans's painting of the Réunion crested starlingNever the most common of birds, the huia inhabited beech and podocarp forests, and was apparently confined to North Island’s Ruahine, Tararua, Rimutaka, and Kaimanawa mountain ranges, with occasional reports from the Wairarapa Valley too. (Supposed sightings of huias from the woody country near Massacre Bay in South Island’s Province of Nelson were never substantiated.) Yet although it had been hunted for generations by the Maoris, who greatly prized its attractive tail feathers for their chiefs’ head-dresses, its numbers seemingly did not suffer unduly until the coming of the Europeans.

Their arrival, however, was accompanied by all manner of serious threats to the huia's survival. These included: the accompanying introduction of Western species that endangered the huia by preying upon it, competing with it for food, and exposing it to various diseases hitherto unknown there; large-scale procurement of huia specimens for museums and private collections; destruction of its forest homelands for cultivation and grazing; and ultimately the widespread wearing of huia plumes by all Maoris (regardless of status) and by members of European high society.

A pair of mounted huias at Germany's Museum für Naturkunde (Haplochromis/Wikipedia)

A pair of mounted huias at Germany's Museum für Naturkunde (Haplochromis/Wikipedia)There could be only one outcome. The last fully verified sighting of this species was made on 28 December 1907, when W.W. Smith spotted two males and a female. Since then, the huia has been officially categorised as extinct – but is it? We'll return to this tantalizing subject a little later.

Meanwhile:

ALBINO HUIAS, RED-TAILED HUIAS, AND THE FORGOTTEN HUIA-ARIKI

It is not widely known that the familiar glossy-black huia with a white-banded tail is not the only variety of huia on record.

For instance, several beautiful albinistic specimens are preserved in various museums, their snowy plumage and pale wattles rendering them almost as a photographic negative of their typical ebony-plumed counterparts. One such specimen, an adult female, was painted in the company of a pair of normal adult huias by celebrated bird artist Johannes G. Keulemans. This beautiful water colour was published in c.1900.

Keulemans's painting of an albinistic female huia and a normal pair

Keulemans's painting of an albinistic female huia and a normal pairIt is well documented that immature huias sometimes exhibited a rufous tinge to their tail's white band. However, Maoris sometimes specifically referred to a 'red-tailed huia' in the adult state too, by which they may have been alluding to specimens retaining this rufous tinge of the white tail band into maturity.

Far more intriguing, however, is the so-called huia-ariki (translated as 'chiefly huia') – a nowadays-forgotten yet extremely distinctive huia variant, whose plumage was decidedly different from that of the normal form. The principal source of information concerning the huia-ariki is Sir Walter Lowry Buller's magnificent and still-definitive work A History of the Birds of New Zealand. Here is what he wrote about it in the 2nd edition (1888):

The most remarkable variety, however, is that known to the Maoris as a Huia-ariki. I have never seen but one of these birds, of which I have already published the following notice*:—

[* = Trans. New-Zealand Instit. 1878, vol. xi. p. 370.]

“I have received from Captain Mair some feathers which, in colour, have much the appearance of the soft grey plumage of Apteryx oweni [nowadays termed Apteryx owenii, the little-spotted kiwi], but which are in reality from the body of a Huia, being of extremely soft texture. I hope to receive the skin for examination, but in the meantime I will give a quotation from the letter forwarding the feathers:—Old Hapuku, on his death-bed, sent for Mr. F. E. Hamlin, and presented him with a great taonga. This has just been shown to me. It is the skin of a very peculiar Huia, an albino I suppose, called by the Hawke’s Bay natives ‘Te Ariki.’ I send you a few feathers. The whole skin is of the same soft dappled colour, but the feathers are longer and softer. The bill is nearly straight, strong, and of full length. The wattles are of a pale canary-colour. The centre tail-feather is the usual black and white, while the others on each side are of a beautiful grey colour. These birds are well known to the Huia-hunting natives of Hawke’s Bay; and to possess an ‘Ariki’ skin one must be a great chief. The specimen I have described was obtained in the Ruahine mountains.”

The skin was afterwards sent to me, for examination, and was exhibited at a Meeting of the Wellington Philosophical Society. It is that of a male bird of the first-year. The whole of the body-plumage is brownish black, obscurely banded or transversely rayed with grey; on the head and neck the plumage is darker, shading into the normal glossy black on the forehead, face, and throat. The tail-feathers are very prettily marked: with the exception of the middle one, which is of the normal character in its apical portion, they are blackish brown, irregularly barred and fasciated with different shades of grey, and with a terminal band of white; the under tail-coverts, also, are largely tipped with white, indicating adolescence.

I have on file a number of examples of freak brown specimens belonging to species whose plumage is normally black, such as crows and certain other corvids. And in some cases, these brown specimens also exhibit a degree of banding or fasciation. This aberrant colouration and patterning was genetically induced in those birds, so presumably the huia-ariki arose from the expression of an analogous – or even homologous - mutant allele in the huia. However, the softer, longer nature of the feathers themselves in the huia-ariki suggests that another mutant allele may also have been involved, unless there was a single, pleiotropic (i.e. multi-potent) allele responsible, affecting separate aspects of this variant's phenotype. I wonder if there is an illustration of the huia-ariki? It would be fascinating to see what this remarkable form looked like, rather than having to rely only upon a verbal description.

A sketch from 1888 of a huia with an aberrant upper mandible

A sketch from 1888 of a huia with an aberrant upper mandibleAlso on record are a few huia specimens with distorted beaks, such as the bizarre example illustrated above.

POST-1907 SURVIVAL OF THE HUIA?

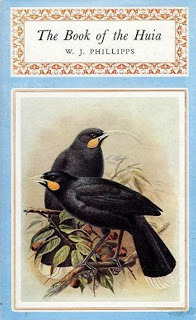

The huia’s morphology is unique. No other bird in New Zealand, whether native or introduced, can be readily confused with it - which is why the sizeable number of alleged post-1907 huia sightings has attracted notable scientific interest. Their most detailed documentation is presented in William I. Phillipps’s The Book of the Huia (1963). A noted expert on New Zealand’s avifauna, Phillipps listed 23 such sightings, and learnt that as recently as the 1920s eyewitness reports of black birds with orange wattles and white-tipped tails regularly emerged from the huia’s former haunts.

The Book of the Huia, by William I. Phillipps

The Book of the Huia, by William I. PhillippsAlthough none were by professional ornithologists, a number of these sightings are sufficiently convincing to give cautious cause for optimism that this unmistakeable species still survived at that time. An official huia search was carried out in 1924, and although no huia were seen, signs of this species’ existence were observed. Moreover, a much more recent event, one that greatly impressed Phillipps, occurred on 12 October 1961, featuring Margaret Hutchinson.

As I learnt from Ron Scarlett of South Island’s Canterbury Museum, when Hutchinson arrived for a six-month stay in New Zealand in 1961 she visited the museum first of all, before travelling on to North Island; she interviewed at length its then Assistant Director, Graham Turbott, regarding the huia, as she seemed most interested in this species. After reaching North Island, she spent October at the Lake House Hotel, Waikaremoana, in the Urewera State Forest, where she was studying the native bush (forest).

On 12 October, Hutchinson spent the day at a smaller lake called Waikareiti, three miles further on from her hotel, and set amidst New Zealand beech woodland. She had been sitting by the track leading to the lake, watching some large, red-and-green native parrots called kakas pecking dead wood off a tree, when suddenly, as she was looking across a small valley nearby, she saw a bird fly up the middle of it, and disappear into some beeches. It was of similar size to the kaka (17-19 in) but was of slighter build, and its plumage was black, except for the white-banded tip of its tail. In the field-guide that she later consulted, the picture most closely matching her bird was the huia’s.

19th-Century engraving depicting a pair of huias

19th-Century engraving depicting a pair of huiasAs she noted in an article published in the RSPB’s Birds magazine (September-October 1970), Hutchinson recounted her sighting not only to William Phillipps but also to Dr R.A. Falla (then Director of Wellington’s Dominion Museum), another major authority on New Zealand birds. Both men were sufficiently impressed to deem it likely that she had genuinely seen a huia; in The Book of the Huia, Phillipps goes so far as to conclude: “...there appears to be little doubt she did see a huia”.

However, we must also consider the possibility that Hutchinson’s evident interest in this species actually conspired against her. Could a combination of excitement and surprise at the bird’s brief and unexpected debut have ‘transformed’ it (albeit unconsciously) in her eyes from its true identity (some still-surviving species, such as a tui) into a huia? In short, could her huia have been an illusion, created unconsciously by an innate desire to see one? The human brain can play some quite extraordinary tricks on our eyes, often ‘filling in’ details that are not actually there, or modifying the appearance of an object to accord with some subconscious thought or memory - and all without the person concerned even realising what is happening.

A mounted female huia (Fritz Geller/Grimm,Wikipedia)

A mounted female huia (Fritz Geller/Grimm,Wikipedia)More recently, in 1991, Copenhagen University zoologist Lars Thomas, who has a longstanding interest in cryptozoology, also claimed to have seen a huia, while visiting North Island’s Pureora Forest.

Yet if the huia really does still survive, why has it not been formally rediscovered by now? In a foreword to Phillipps’s book, Falla noted that even at best, New Zealand’s bush is not overly conducive to easy birdwatching, requiring such a sustained effort to explore the multitude of potential hideaways for birds that there is rarely enough time to carry out detailed observations at any one given spot, so that all-too-many of its birds are not sighted at all. Having spent quite some time birdwatching in New Zealand during 2006, I can certainly vouch for this.

A New Zealand postage stamp issued in 1898 featuring a pair of huias

A New Zealand postage stamp issued in 1898 featuring a pair of huiasIf the huia is alive, it has probably retreated into areas that even by the bush’s standards are quite inaccessible, and thus less readily disturbed. Indeed, over the years a number of people have informed Ron Scarlett of possible huia sightings in the remoter regions of the Kaimanawa range, so that he deems it possible that the species still survives here. Moreover, as Hutchinson revealed in her article, careful analysis of the post-1907 reports documented by Phillipps do seem to indicate a movement northwards — away from the huia’s most favoured former provenance, the Tarawera Range (now divided up by agricultural cultivation), and into a wilder, mountainous forest region (much less accessible to humans), perhaps as far as the Urewera State Forest after all.

Equally, Ron Scarlett has identified subfossil huia bones from moa-hunter middens on the Taranaki coast, and from limestone caves in the Mahoenui area, lying on the border of North Taranaki and South Auckland, and much further north than the huia’s known modern-day distribution. Could this region’s more remote portions be another putative retreat of surviving huias?

Perhaps some huias took refuge in certain northern areas less readily reached by humans during their species’ last stand in its favoured territory. In addition, there might be areas that have always housed a resident huia population, wholly unknown to the Europeans, so that this truly unique species - New Zealand’s handsome and quite astonishing bird with two beaks - still survives after all.

RESURRECTING THE HUIA? SEND IN THE CLONES!