Karl Shuker's Blog, page 51

October 10, 2013

THE GIANT RAT OF SUMATRA – ZOOLOGICAL FACT, NOT SHERLOCK HOLMES FICTION

"Matilda Briggs was not the name of a young woman, Watson,” said Holmes, in a reminiscent voice. “It was a ship which is associated with the giant rat of Sumatra, a story for which the world is not yet prepared..."

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – ‘The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire’, from The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes (1927)

Contrary to the assumption by many aficionados of the Sherlock Holmes stories that it was wholly fictional, there really is a giant rat of Sumatra. Yet despite having been scientifically described as long ago as 1888 (by eminent mammalogist Oldfield Thomas of London's Natural History Museum), until as recently as the 1980s it had remained largely a mystery, even to zoologists.

In 1983, however, following an in-depth study of this mighty 2-ft-long rodent, Dr Guy G. Musser (Curator of Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History) and museum research student Cameron Newcomb attempted to disperse the longstanding veil of obscurity surrounding it by publishing its very first full scientific description. Their paper appeared in the museum’s Bulletin.

The real Sumatran giant rat, Sundamys infraluteus (© hgeorge/Hong Kong Bird Watching Society)

The real Sumatran giant rat, Sundamys infraluteus (© hgeorge/Hong Kong Bird Watching Society)A very large, mountain forest-dwelling species with dense, woolly, dark-brown fur (characterised by extremely lengthy guard hairs) and powerful jaws, the Sumatran giant rat had traditionally been categorised as a typical, Rattus rat. After a meticulous investigation of its anatomy, however, one that surely would have met with Holmes’s own approval, Musser and Newcomb recognized that its aural, nasal, and dental characteristics fully justified separation of this legendary form from the Rattus horde. As a result, they officially rehoused it in a new genus, Sundamys, along with two other Asian species.

The Sumatran giant rat (© Karen Phillipps)

The Sumatran giant rat (© Karen Phillipps)The Sumatran giant rat is now known formally as Sundamys infraluteus, and is not deemed to be endangered, being recorded not only from a sizeable area of Sumatra but also from both Malaysian and Indonesian Borneo. Its two congeners are Bartels's rat S. maxi, and Müller's giant Sunda rat S. muelleri.

Formally described in 1931 as a valid species but later classified merely as a subspecies of the Sumatran giant rat until re-elevated to the rank of a species in its own right by Musser and Newcomb in their 1983 paper, Bartels's rat remains scarcely-known even today. It is represented only by 21 specimens collected between 1932 and 1935 from two locations on Java by Max Bartels Jr, and is categorized as Endangered by the IUCN.

Muller's giant Sunda rat (© asiakarsts.wordpress.com)

Muller's giant Sunda rat (© asiakarsts.wordpress.com)As for Müller's giant Sunda rat: originally described in 1879, this species has the widest distribution of the Sundamys trio, being recorded from Indonesia (including Borneo's Indonesian region and Sumatra, but not Java), Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Thailand, and is not deemed to be endangered. It is a primarily terrestrial, lowland species.

My Sherlock Holmes toby jug, with the Hound of the Baskervilles stealing the scene as usual! (Dr Karl Shuker)

As a longstanding Sherlock Holmes fan, I'm aware that although the giant rat of Sumatra's case was never documented by Dr Watson within the original, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle canon of Sherlock Holmes fiction, it has inspired several pastiches penned by other authors, yielding an extremely diverse range of identities for it.

Richard L. Boyer's giant rat of Sumatra novel

Richard L. Boyer's giant rat of Sumatra novelThese include such memorable candidates as a tapir, in Richard L. Boyer's novel The Giant Rat of Sumatra (1976); a monstrous mega-rat called Harat who rules a nation of sub-humans in Alan Vanneman's novel Sherlock Holmes and the Giant Rat of Sumatra (2003) (not to be confused with an entirely different but identically-titled novel by Paul D. Gilbert, published in 2010); and, perhaps most bizarrely of all, a preternatural maritime horror, in a story penned by none other than H.P. Lovecraft!

Alan Vanneman's giant rat of Sumatra novel

Alan Vanneman's giant rat of Sumatra novelThe mega-murid also appears in a novel featuring what must be the most extraordinary literary pairing ever – Sherlock Holmes and Count Dracula! These two iconic if diametrically dissimilar figures reluctantly join forces to confront a nefarious plot to destroy London using plague-bearing rats in Fred Saberhagen's The Holmes-Dracula File (1978), with the giant rat of Sumatra being the principal vector.

Paul D. Gilbert's giant rat of Sumatra novel

Paul D. Gilbert's giant rat of Sumatra novelThis rangy rodent has even left its mark in the theatre, with a number of plays having featured it over the years. Notable among these are the Fossick Valley Fumblers theatre group's production, 'Sherlock Holmes and the Giant Rat of Sumatra', written by Bob Bishop, and debuting at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in August 1995; and an entirely separate but identically-titled comedy musical with music and lyrics by Jack Sharkey and book by Tim Kelly, which was first performed on 31 December 1986, by the Magnificent Moorpark Melodrama & Vaudeville Theatre, Moorpark, California, USA.

The Fossick Valley Fumblers 1990s play

The Fossick Valley Fumblers 1990s playMoreover, Wikipedia has an entire 'Giant Rat of Sumatra' page (click here ) containing a very lengthy listing of other literary works (plus some music and TV productions) inspired by this evocative furry entity, as can readily be seen in the screenshot below of that listing.

Giant rat of Sumatra literary, music, and TV spin-offs - click to enlarge (Wikipedia)

Giant rat of Sumatra literary, music, and TV spin-offs - click to enlarge (Wikipedia)All in all, a pretty impressive modern-day C.V. for a quasi-cryptid originally only mentioned very briefly in passing by a fictitious detective almost a century ago.

Published on October 10, 2013 15:10

October 7, 2013

I THOUGHT I SAW A TERROR SAUR! - DO PREHISTORIC FLYING REPTILES STILL EXIST?

Are there living pterosaurs in Zambia's swamplands?

Those iconic winged reptiles of prehistory known as the pterosaurs died out alongside the last dinosaurs over 60 million years ago…didn’t they? Most mainstream zoologists would say that they did. Then again, most mainstream zoologists have probably never heard of the kongamato, the ropen, the duah, or a veritable phalanx of other winged mystery beasts reported from around the world that bear a disconcerting resemblance to those supposedly long-vanished rulers of the ancient skies. Could these cryptozoological creatures possibly be surviving pterosaurs? Read their histories here, and judge for yourself.

THE KONGAMATO – AN AFRICAN ANOMALY

The Jiundu marshes of western Zambia’s Mwinilunga District comprise a huge but remote expanse of densely-foliaged, forbidding, near-impenetrable swampland rarely visited even by the native people, let alone Westerners. This is due in no small way to the persistent local belief that this foetid morass is home to a frightening horror of a creature whose very name strikes terror among the neighbouring populace – the kongamato. It first attracted popular attention in 1923, when documented in traveller Frank H. Melland’s book In Witchbound Africa. Discussing it with the local Kaondé people, Melland learnt that this greatly-feared entity allegedly resembles a reddish-coloured lizard with membranous bat-like wings measuring 1-2 m across, a long beak crammed with teeth, and no fur or feathers on its body, just bare skin. When shown books filled with pictures of animals living and extinct, every native present immediately selected pictures of pterosaurs and identified them as representations of the kongamato. And indeed, there is no doubt that the above description of a kongamato bears a startling similarity to that of certain early, medium-sized pterosaurs known as rhamphorhynchoids, typified by their toothy beaks, as well as their long tails (the later pterodactyloids lacked teeth and tails). Nor were reports of such an animal limited to Zambia (then Northern Rhodesia).

Kongamatos attacking boats (William Rebsamen)

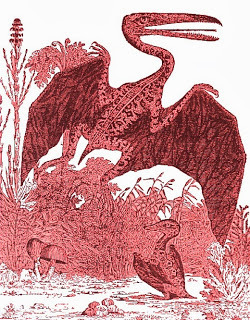

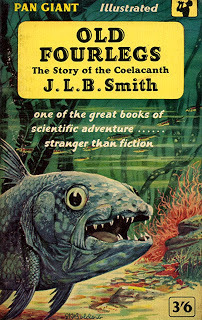

Kongamatos attacking boats (William Rebsamen)At much the same time, accounts of an identical mystery beast were also emanating from a comparably dense, inhospitable swamp in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and during the 1940s game warden Captain Charles R.S. Pitman referred to the reputed existence of a pterodactyl-like creature amid swamp forests near the border of Angola and the Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Congo). So-called flying dragons were even mentioned by celebrated South African ichthyologist Prof. J.L.B. Smith – immortalised as the co-discoverer of another prehistoric survivor, the lobe-finned coelacanth fish back in 1938. In his book Old Fourlegs(documenting the coelacanth’s discovery), he noted that the descendants of a missionary who had lived near Mount Kilimanjaro in East Africa had long heard reports and claimed sightings of such beasts from the local people. Prof. Smith was even bold enough to state: “I did not and do not dispute at least the possibility that some such creature may still exist” – and, as someone who had recently resurrected another prehistoric lineage from many millions of ‘official’ extinction, his opinion could not be readily discounted.

My Pan paperback first edition of Old Fourlegs (Pan Books)

My Pan paperback first edition of Old Fourlegs (Pan Books)During the 1950s, there was much correspondence in Rhodesian newspapers on the subject of living pterosaurs, in which several zoologists, but most notably Dr Reay Smithers – director of Southern Rhodesia’s National Museum – attempted to dismiss such a notion by offering various modern-day candidates as the identity of these winged wonders. The most popular one was the shoebill Balaeniceps rex - a large superficially stork-like bird with an enormous beak, and a very impressive wingspan, which can indeed appear deceptively prehistoric when seen in flight, especially by someone not familiar with this unusual species. However, also on file are reports of natives claiming to have been attacked and severely wounded by the kongamato when it has stabbed them with its long beak - something that the shy shoebill, whose beak is in any case the wrong shape to accomplish such a deed, is unlikely to do.

The shoebill (Wikipedia)

The shoebill (Wikipedia)In one instance from the 1920s, a native boldly decided to penetrate a vast Southern Rhodesian swamp traditionally deemed by his tribe to be the abode of demons, from which no-one who entered it ever returned alive, and see for himself just what did inhabit this accursed realm. Happily, he did return alive – but only just, having been badly injured, resulting in a major chest wound. When a civil servant for the region asked him what had happened, the native told him that he had encountered a huge bird of a type that he had never seen before, with a long sharp beak. Shown a book of animal pictures, he flicked through it in a desultory manner – until he came to an illustration of a pterodactyl, whereupon he let out a terrified shriek and ran out of the civil servant’s house. A comparable incident was reported from Zambia’s Lake Bangweulu swamps during the 1950s, and when the wounded native, who was taken to a Fort Rosebery hospital, was given some paper and a crayon to sketch the creature that had attacked him, the result was a silhouette that corresponded precisely with that of a pterodactyl.

Moreover, at much the same time, while working in the Zambezi Valley, Daily Telegraphcorrespondent Ian Colvin not only saw but actually photographed what was later claimed by one observer to be a pterodactyl. Zoologists disagreed, some stating that it was a shoebill, others a saddle-backed stork Ephippiorhynchus senegalensis – a tall bird with a very long beak that could certainly cause the kind of chest injuries noted above but which bears no resemblance to a pterosaur (or, incidentally, to a shoebill). Nor can a mammalian identity, such as a bat or gliding rodent, provide a convincing answer.

Saddle-billed stork (hyper7pro/Flickr/Wikipedia)

Saddle-billed stork (hyper7pro/Flickr/Wikipedia)Attempts have also been made to explain away native beliefs in pterosaurian monsters as the result of cross-cultural contamination – their beliefs influenced by the discovery in those African regions of pterosaur fossils. However, cryptozoological researches have shown that such beliefs considerably predate any palaeontological discoveries made there.

Today, Africa’s neo-pterosaurs have been largely forgotten in the wake of other, newer cryptozoological stars, but the Jiundu swamps and similar ‘monster-haunted’ terrain still exist, awaiting exploration by anyone enthusiastic, and brave, enough to venture into their shadowy realms in search of their mysterious, potentially deadly inhabitants.

WINGING ACROSS THE AMERICAS

Amazing as it may seem, some of the most compellingly pterosaurian mystery beasts on record have been reported not from the remote wildernesses of tropical Africa but from the supposedly well-explored heartlands of North America, with Texas as the epicentre of such sightings.

Perhaps the single most dramatic modern-day pterosaur report from the New World is that of ambulance technician James Thompson, who was driving along Highway 100 to Harlingen, midway between Raymondville and Brownsville (two Texas towns that had both previously hosted pterosaur reports), on 14 September 1983 when an extraordinary creature flew across the road about 50 m ahead of him with distinct flapping wingbeats. He was so amazed by what he had seen that he stopped his ambulance and got out to get a better look at it. In his subsequent description, Thompson stated that the creature was 2.5-3-m long, with a thin body and a long tail that ended in a fin, a wingspan at least equal to the ambulance’s width (roughly 2 m), a virtually non-existent neck, but a hump on the back of its head, a pouch-like structure close to its throat, and a rough, featherless, blackish-grey skin

Attempts by others to identify what Thompson had seen with mainstream identities such as a pelican (suggested by its throat pouch but not explaining its tail fin or lack of feathers) and even an ultralight aircraft (since when have these been able to flap their wings?!) failed miserably. The only creature living or extinct that resembles it is a rhamphorhynchoid pterosaur, known to have possessed a long tail terminating in a fin.

Modern-day reconstruction of a rhamphorhynchoid pterosaur (public domain)

Modern-day reconstruction of a rhamphorhynchoid pterosaur (public domain)A remarkably similar beast was sighted during much the same time period, flying roughly 40 m away at a height of about 16 m off the ground, by Richard Guzman and a friend, Rudy, one early evening in Houston. A sketch produced by Guzman appears in Ken Gerhard’s book Big Bird! (2007), and depicts an indisputably pterosaurian entity – complete with a prominent bony head crest and a long finned tail (crests are traditionally a pterodactyloid characteristic, but at least two fossil rhamphorhynchoids are now known to have been crested too).

Ken Gerhard (CFZ)

Ken Gerhard (CFZ)In his book, Ken notes how, after interviewing Guzman personally (on 9 October 2003), he then read out loud from his copy of my own book In Searchof Prehistoric Survivors (1995) my documentation of Thompson’s sighting to an enthralled Guzman who, inexplicably, had not seen my book before (what?!!), and had not previously known about Thompson’s encounter.

Another notable Texan sighting had taken place back on 24 February 1976, when three school teachers driving along a lonely road southwest of San Antonio saw a huge shadow fall across the road, and when they looked up were shocked to spy a monstrous flying creature soaring overhead with a wingspan estimated by them to be 5-6 m. Its body was encased in a grey skin and its wings were membranous, seeming to them to be distinctly bat-like. They were unable to name what they had seen until, after perusing several encyclopedias, they finally came upon a creature that resembled it – America’s giant Cretaceous pterosaur, Pteranodon.

Reconstruction of Pteranodon in flight (Dr Karl Shuker)

Reconstruction of Pteranodon in flight (Dr Karl Shuker)Perhaps the most controversial case involving a reputed modern-day American pterosaur was supposedly reported by the Tombstone Epitaph newspaper on 26 April 1890, six days after the event in question had occurred. Two ranchers riding through the Huachuca desert not far from Tombstone had allegedly encountered a gigantic monster stranded on the ground and flapping its leathery featherless wings frantically as it attempted to become airborne. With a gargantuan total length of 30 m and a colossal wingspan of around 50 m, not to mention a massive beak filled with teeth, this terrifying entity petrified the ranchers – until, that is, they opened fire with their Winchester rifles, killing it outright. To confirm their story, they cut off one of the creature’s wingtips and took it back home with them, but what became of it is a mystery – just like the story itself, because no-one has so far succeeded in tracing the elusive newspaper report describing it.

However, in 1969, an elderly man called Harry McClure read about this alleged incident in a magazine, and announced that he had actually known the ranchers in question as a young man, and remembered the incident well. Even so, he claimed that it had been greatly exaggerated, stating that the beast had ‘only’ been 6.5-9 m long, possessed a single pair of sturdy legs and very large eyes, and had twice tried to become airborne before being shot at (but not killed) by the ranchers, who finally abandoned it, still attempting to take flight.

This representation of an alleged desert-stranded Tombstone pterosaur is more like a winged crocodile! (Orbis Publishing)

This representation of an alleged desert-stranded Tombstone pterosaur is more like a winged crocodile! (Orbis Publishing)Pterosaur reports have also emerged from Mexico, and from South America. The late J. Richard Greenwell, onetime secretary of the International Society of Cryptozoology, had a Mexican correspondent who claimed that there are living pterosaurs in Mexico's eastern portion and was (still is?) determined to capture one, to prove beyond any shadow of doubt that they do exist. Worthy of note is that certain depictions of deities, demons, and strange beasts from ancient Mexican mythology are decidedly pterodactylian in appearance. One particularly intriguing example is the mysterious 'serpent-bird' portrayed in relief sculpture amid the Mayan ruins of Tajin, in Veracruz's northeastern portion - noted in 1968 by visiting Mexican archaeologist Dr José Diaz-Bolio, and dating from a mere 1000-5000 years ago. Yet all pterosaurs had officially become extinct at least 64 million years ago. So how do we explain the Mayan serpent-bird - a non-existent, imaginary beast, or a creature lingering long after its formal date of demise? Although neither solution would be unprecedented, only one is correct - but which one?

Around February 1947, J.A. Harrison from Liverpool was on a boat navigating an estuary of the Amazon river when he and some others aboard spied a flock of five huge birds flying overhead in V-formation, with long necks and beaks, and each with a wingspan of about 3.75 m. According to Harrison, however, their wings resembled brown leather and appeared to be featherless. As they soared down the river, he could see that their heads were flat on top, and the wings seemed to be ribbed. Judging from the sketch that he prepared, however, they bore little resemblance to pterosaurs, and were far more reminiscent of a large stork - three of which, the jabiru Jabiru mycteria, maguari Ciconia maguari, and wood ibis (aka wood stork) Mycteria americana, are native here.

Wood ibis in flight (Dennis Hawkins/Wikipedia)

Wood ibis in flight (Dennis Hawkins/Wikipedia)In any case, it is North America, which was once home to such prehistoric giant versions as Pteranodonand Quetzalcoatlus, where most alleged pterosaur sightings have been claimed within the New World, leading some cryptozoologists to speculate whether these latter forms have undiscovered descendants existing here. It seems exceedingly unlikely, but the sightings remain on file to tantalise and bemuse, with conservative identities such as pelicans and condors failing to match eyewitnesses’ descriptions.

Having said that: one early evening in 2007, I was standing at the top of Sugarloaf Mountain in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, when, looking upwards, I was startled to see a number of superficially pterosaurian creatures circling high above in the sky overhead. Raising my trusty birdwatching binoculars to my eyes, however, swiftly dispersed the illusion, as these putative prehistoric survivors were instantly exposed as frigate birds (specifically the magnificent frigate bird Fregata magnificens).

Magnificent frigate birds in flight (David Adam Kess/Wikipedia)

Magnificent frigate birds in flight (David Adam Kess/Wikipedia)These long, angular-winged relatives of pelicans do appear positively primeval on first sight, and might well deceive ornithologically-untrained eyes into believing that they had truly witnessed a phalanx of flying reptiles from the ancient past.

NOT IN NEW ZEALAND, SURELY…?

New Zealand, a land of many indigenous birds but few reptiles and even fewer mammals, is surely the last place one might expect to encounter any kind of 20th-Century pterosaur, let alone a multicoloured one. Nevertheless, according to Whangarei resident Phyllis Hall, some time prior to the early 1980s she had been walking along a new motorway, not yet opened to traffic, when a strange creature that looked to her like a pterodactyl flew “out of nowhere”. Its under-wings were blue, but the rest of it was red, and it flew with an undulating motion. This description does not fit anything known to exist anywhere in New Zealand.

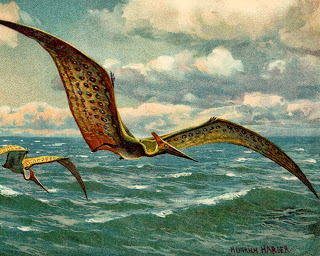

A delightful late 1800s/early 1900s illustration of pterodactyls (Heinrich Harder)

A delightful late 1800s/early 1900s illustration of pterodactyls (Heinrich Harder)CRYPTO-CRETE

Greek mythology tells of many winged monsters, including the harpies and the Stymphalian birds, but I don’t recall any mention of pterodactyls. Nevertheless, Crete was the setting for the appearance of just such a creature, it would seem, when, one morning in summer 1986, three young hikers passing by a river in the Asterousia Mountains saw a bizarre creature flying overhead. They described it as resembling a giant dark-grey bird but with bat-like wings that sported finger-like projections at their tips, long sharp talons, and a pelicanesque beak. It reminded all three of them of a pterodactyl (though it is true that boys do tend to be more clued-up regarding dinosaurs and other prehistoric monsters than birds), and certainly their description sounds more pterosaurian than avian. Conversely, it hardly need be said that a colony of modern-day pterosaurs on Crete would surely have been uncovered by science long ago.

NEWS FROM NEW GUINEA

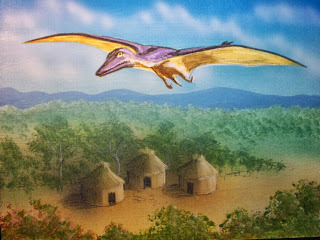

The most recent pterosaur-lookalike to attract attention is not one mystery beast but two. During the late 1990s, stories of a gigantic luminous pterodactylian creature termed the ropen emerged from missionaries based in Papua New Guinea. With a 6-7-m wingspan, a Pteranodon-like bony crest on its head, and a glowing underside (highly-reflective scales?), it had been seen circling over a lake, and resting in a mountain cave.

Could highly-reflective scales explain reports of glowing pterodactylian cryptids in Papua New Guinea? (Tim Morris)

Could highly-reflective scales explain reports of glowing pterodactylian cryptids in Papua New Guinea? (Tim Morris)However, when field cryptozoologist Bill Gibbons later contacted me with full details, he revealed that this beast was actually known as the duah, and that a second, much smaller mystery pterosaur was the true ropen, which was found only on two small offshore New Guinea islands – Rambutyo and Umboi. Sporting a 1-m wingspan, a slender tail tipped with a diamond-shaped fin, and a long beak brimming with teeth, this ropen seems much closer in appearance to the rhamphorhynchoids. It is said to inhabit caves, but is greatly attracted by the smell of rotting flesh – so much so that it has been known to attack funeral gatherings – and will also snatch fish out of the boats of native fishermen (a trait reported for the Zambian kongamato too).

The ventrally-aglow duah (William Rebsamen)

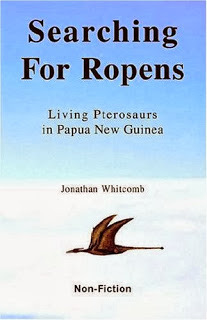

The ventrally-aglow duah (William Rebsamen)Investigator Bruce Irwin visited Papua New Guinea in summer 2001 and interviewed several native eyewitnesses, who confirmed that back in the 1970s the duah had been much more common and used to be seen flying together in small groups at night, but nowadays only solitary specimens were observed. Visiting the nearby island of Umboi to investigate ropen sightings there, Irwin interviewed a policeman and other locals who had seen it, and on nearby Manaus Island he spoke to a school headmaster who saw one in a tree on Goodenough Island, but he did not succeed in doing so himself. Fellow investigator Jonathan Whitcomb also interviewed eyewitnesses on Umboi, including some who claimed to have spotted a huge specimen (a duah?) while hiking near Lake Pung as boys in or around 1994, - as revealed in Jonathan’s book Searching For Ropens: Living Pterosaurs In Papua New Guinea (2006), which is the first of several authored by him on the subject of living pterosaurs there and elsewhere around the world.

Searching For Ropens

Searching For Ropens

There seems little doubt that something very unusual, which cannot be readily dismissed as either a bird or a mammal, is being seen in various far-flung regions of the world. Whether it is truly a living pterosaur is another matter entirely. After all, there are no pterosaur fossils on record from beyond the end of the Cretaceous Period, 64 million years ago. Then again, many modern-day reports come from areas such as tropical forests where fossilisation is rare, or from inaccessible mountain ranges where fossils have not been sought. Ultimately, only physical evidence can confirm just what these winged wonders are, but in view of what happened to the brave native investigator who sought one such creature amid Southern Rhodesia’s nightmarish swamplands, only to re-emerge with a serious chest injury, such an undertaking is clearly not for the fainthearted.

As veteran cryptozoologist Dr Bernard Heuvelmans once wrote: “The trail of unknown animals sometimes leads to Hell”.

For more information on putative living pterosaurs, check out my book In Search of Prehistoric Survivors (1995).

Keeping my distance from a life-sized, unnervingly animatronic Quetzalcoatlus (Dr Karl Shuker)

Keeping my distance from a life-sized, unnervingly animatronic Quetzalcoatlus (Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on October 07, 2013 07:14

September 27, 2013

MOTHMEN AND OWLMEN AND MANBATS, OH MY! – WELCOMING KEN GERHARD'S LATEST BOOK, 'ENCOUNTERS WITH FLYING HUMANOIDS'

Ken Gerhard's latest book, Encounters With Flying Humanoids: Mothman, Manbirds, Gargoyles and Other Winged Beasts

Ken Gerhard's latest book, Encounters With Flying Humanoids: Mothman, Manbirds, Gargoyles and Other Winged BeastsToday, I received through the post a copy of Encounters With Flying Humanoids: Mothman, Manbirds, Gargoyles and Other Winged Beasts. This is the latest book by renowned American cryptozoologist Ken Gerhard, who had added a very kind handwritten inscription to my copy before posting it to me – thanks Ken!

Several months ago, Ken had asked me if I'd write a foreword to his book, and after reading its manuscript I was only too happy to do so, as I was very pleased that these extraordinary and extremely diverse entities' reports had finally been compiled and assessed within a single volume, in so expert and enthralling a manner too.

As I wrote in my foreword, I've always been interested in this subject, ever since encountering by chance many years ago a fascinating book that included a number of different examples. But why waste time attempting to summarise what I wrote in my foreword? Far better simply to reproduce it in full here, as my personal, unequivocal recommendation to everyone interested in such beings, such 'things with wings', to purchase Ken's excellent new book without delay!

One afternoon during the early 1980s, I was browsing through the upstairs, second-hand department of Andromeda Books – the once-celebrated but now long-demised science-fiction and fantasy bookshop in Birmingham, England – when I came upon a paperback entitled Earth's Secret Inhabitants, which had been published in 1979. Its front cover illustration was extremely eyecatching – a full-colour depiction of two feathery-winged humanoids flying through the sky in a scene captured within the hulking silhouette of a bigfoot-type man-beast.

Initially, I'd assumed that this book was a sci-fi novel, but then I noticed that its authors were none other than D. Scott Rogo and Jerome Clark – two leading American non-fiction writers specialising in the field of mysterious phenomena. And when I turned to the back cover, the blurb revealed that its contents featured a wide range of surreal entities that apparently share our planet with us but have never been scientifically explained - including a veritable phalanx of winged 'bat-men'. Until then, I'd been largely unaware of these aerial apparitions, but after reading about them in Rogo and Clark's book – because, needless to say, I purchased it immediately! – I was totally captivated by their bizarre histories and extraordinary appearance, and from then on I made a point of collecting as much information concerning them as I could find.

My much-read copy of Earth's Secret Inhabitants (Dr Karl Shuker/Tempo Books)

My much-read copy of Earth's Secret Inhabitants (Dr Karl Shuker/Tempo Books)The most immediate problem that I have always faced whenever doing so, however, is that such material is extremely disparate, scattered loosely among countless publications, yet rarely compiled or assimilated into any kind of lucid or lengthy coverage. This is why I was delighted to learn recently that Ken Gerhard was writing a book-length treatment of these winged wonders, and even more delighted when he very kindly invited me to write a foreword for it.

Reading through his book, Encounters With Flying Humanoids, it is evident that Ken shares my own fascination with the bat-men and man-birds that have haunted our skies for many centuries, continue to be encountered even today, in all parts of the world, and assume a diverse assortment of forms. Moreover, unlike previous writers, he has not been content to limit his coverage to such perennially-chronicled enigmas as mothman, owlman, and the man-bats of Texas, but has cast his gaze like a vast skyborne net far and wide through time and space, encompassing many much more obscure examples that even I, despite having spent years of collecting material myself, had never previously heard of.

Consequently, Encounters With Flying Humanoids very commandingly fills a sizeable, (all-too-)long-present gap in the Fortean and cryptozoological literature, and it also makes enthralling, if not a little disturbing, reading. What are these mysterious flying figures with plumes of bird or pinions of bat, and where have they originated? Do they truly belong somewhere within our planet's grand scheme of things, or are they visitors from the great beyond – from alien worlds, planes, or dimensions, rarefied realms stranger than we can even begin to suspect? And if so, why are they here? What might their purpose be?

A worthy successor to his previous highly-acclaimed volumes on winged mystery beasts and cryptids of Texas, Ken's latest, superb book is a timely reminder of just how outlandish our land can sometimes be, how otherworldly our world may sometimes seem, and that there truly are more things – especially with wings – in heaven and earth, gentle reader, than are dreamt of in anyone's philosophy!

Click here to purchase Ken's book from Amazon.

With my very own flying humanoid! (Dr Karl Shuker)

With my very own flying humanoid! (Dr Karl Shuker)

Published on September 27, 2013 15:27

September 19, 2013

GIANT ANACONDAS AND OTHER SUPER-SIZED CRYPTOZOOLOGICAL SNAKES

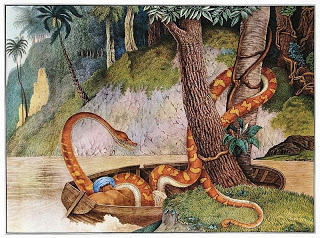

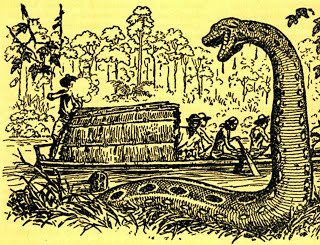

1867 engraving of a giant snake, from The Bestiarium of Aloys Zötl 1831-1887

1867 engraving of a giant snake, from The Bestiarium of Aloys Zötl 1831-1887 During the 1920s, Raymond L. Ditmars, Curator of Reptiles at New York's Bronx Zoo, offered US $1000 to anyone who could provide conclusive evidence for the existence of a snake measuring over 40 ft (12.2 m) long. The prize has never been claimed. Yet there are many extraordinary eyewitness accounts on record asserting that gargantuan serpents far greater in length than anything ever confirmed by science are indeed a frightening reality in various regions of the world, as demonstrated by the fascinating selection of examples documented here.

THE GIANT SERPENT OF CARTHAGEAND OTHER OLD WORLD GOLIATHS

During the time of Rome's First Punic War (264-241 BC) with Carthage (which lay near present-day Tunis in Tunisia, North Africa), the Roman army, led by the renowned general Marcus Atilius Regulus, was advancing on Carthage, having reached the River Bagradas (aka Medjerda). As his battalions sought to cross this river, however, an enormous snake rose up before them from the reed beds, with great flattened head and glowing lantern-like eyes glaring malevolently at them as they cowered back at the sight of this monstrous reptile. Coil after coil in seemingly limitless extent emerged, and the soldiers estimated its vast length to be at least 30 m!

18th-Century colour engraving of a rock python, the likely identity of Carthage's giant snake

Deciding that discretion may well be the better part of valour, Regulus's army retreated further down the river bank, hoping to cross far away from its ophidian guardian. And when they looked back, the giant snake had seemingly vanished. Yet no sooner did they attempt to cross at this new location than, without warning, the huge flattened head rose up from below the water surface and seized a nearby soldier in its mighty jaws, enfolding and crushing his body in its vice-like constricting coils, before mercilessly drowning him. And each time another soldier tried to cross, this grisly scene was re-enacted.

In fury, Regulus ordered his men to wheel forward and arm their siege ballistae – massive catapults used for hurling immense rocks at fortresses. Missile after missile was duly fired at the snake, bombarding it unceasingly until, wounded and dazed, the huge creature finally began to retreat into the river. But before it could submerge itself completely, a well-aimed rock hit it squarely between its eyes, shattering its skull and killing outright this veritable leviathan of the serpent world. Afterwards, the soldiers skinned its colossal body, and records preserved from that time claim that its skin measured a tremendous 37 m. This stupendous trophy and also the snake's formidable jaws were eventually brought back to Rome and placed on display inside one of the temples on Capitol Hill. Here these spectacular relics remained until 133 BC, when, towards the end of the Numantine War against the Iberian Celts, they mysteriously disappeared, and were never reported again.

A rock python, southern subspecies

A rock python, southern subspeciesAlways assuming that this Carthaginian mega-serpent's size had been recorded accurately, what could it have been? A rock python Python sebae is the most popular identity, but this species is not thought to have existed at any time in that particular area of Africa. And even where it is known to exist, no specimen even remotely as long as Regulus's antagonist has ever been chronicled. The longest confirmed specimen, measuring 9.81 m, was shot in school grounds at Bingerville, Ivory Coast, by Mrs Charles Beart in 1932.

The same applies to an astonishing report from tropical Africa featuring an extremely reliable eyewitness. In 1959, an ostensibly immense python reared up towards a helicopter passing overhead in Katanga (within what is now the Democratic Congo), flown by Belgian military pilot Colonel Remy van Lierde. He actually managed to snap a photograph of the creature, and using the size of background bushes and other topographical features in the photo as scale determinants the python appeared to be around 15.5 m long – once again far greater than any scientifically-confirmed specimen.

The gargantuan Katanga mystery snake (Colonel Remy van Lierde)

The gargantuan Katanga mystery snake (Colonel Remy van Lierde)Native to southeast Asia, the world's longest species of snake is the reticulated python Python reticulatus. Its current confirmed record-holder, measuring 10 m, was shot on the north coast of Sulawesi (Celebes) in 1912, and was accurately measured by civil engineers using a surveying tape. In summer 1907, however, a dark cane-coloured python estimated at 70 ft (21.3 m) long had been observed through binoculars swimming in the Celebes Sea by Third Officer S. Clayton of the China Navigation Company's vessel Taiyuan.

THE SUCURIJU GIGANTE – SOUTH AMERICA'S SUPER-SIZED ANACONDA

According to the record books, South America's common or green anaconda Eunectes murinus rarely exceeds 6.25 m. Yet there are numerous reports of specimens far bigger than this. Indeed, such monsters even have their own local names, such as the sucuriju gigante in Brazil and the camoodi in Guyana. Sometimes they are also said to bear a pair of horns on their head.

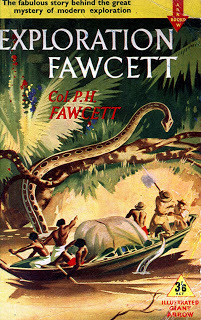

Exploration Fawcett

– front cover depicting Fawcett's encounter with a giant anaconda (Arrow Books)

Exploration Fawcett

– front cover depicting Fawcett's encounter with a giant anaconda (Arrow Books)Perhaps the most (in)famous encounter with a purported sucuriju gigante occurred in 1907, when, while leading an expedition through the Amazonian rainforest in Brazil's Acre State, the celebrated, subsequently-lost explorer Lieutenant-Colonel Percy Fawcett shot a massive anaconda as it began to emerge from the Rio Abuna and onto the bank. In his book Exploration Fawcett, he claimed that as far as it was possible to measure the body, a length of 13.7 m lay out of the water, with a further 5.2 m still in it, yielding a total length of 18.9 m. Even though Fawcett was known for his meticulous observations, this claim is nowadays viewed with scepticism by many zoologists.

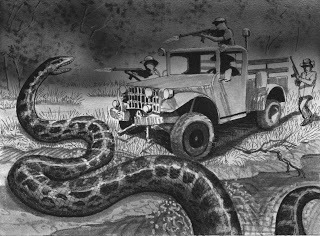

Drawing of Fawcett shooting the giant anaconda (source unknown to me)

Drawing of Fawcett shooting the giant anaconda (source unknown to me)On 22 May 1922 at around 3 pm, priest Father Victor Heinz witnessed a sucuriju gigante while travelling home by canoe along the Amazon River from Obidos in Brazil's Pará State. He and his petrified crew saw about 27.5 m away in midstream a huge snake, coiled up in two rings, and they gazed in awe as it drifted passively downstream. Fr Heinz estimated its visible length at just under 24.5 m, and stated that its body was as thick as an oil drum.

Sucuriju gigante encountered by Father Heinz and his crew (William Rebsamen) Moreover, on 29 October 1929 he encountered another specimen, this time while he and his crew were travelling by river to Alenquer in Brazil's Pará State at around midnight. Approaching them in the dark from the opposite direction, its eyes were so large and phosphorescent that he initially mistook them for a pair of blue-green navigation lights on a steamer! Happily, this monstrous serpent paid no attention to its terrified observers!

Sucuriju gigante encountered by Father Heinz and his crew (William Rebsamen) Moreover, on 29 October 1929 he encountered another specimen, this time while he and his crew were travelling by river to Alenquer in Brazil's Pará State at around midnight. Approaching them in the dark from the opposite direction, its eyes were so large and phosphorescent that he initially mistook them for a pair of blue-green navigation lights on a steamer! Happily, this monstrous serpent paid no attention to its terrified observers! Illustration of a giant anaconda coming ashore (William Rebsamen)

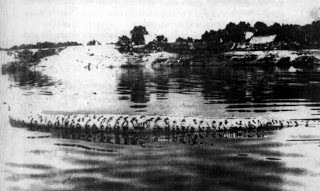

Illustration of a giant anaconda coming ashore (William Rebsamen)The following photograph depicts an alleged 40-45-m-long sucuriju gigante that according to Tim Dinsdale's book The Leviathans (1966) was originally captured alive on the banks of the Amazon and towed into Manaos by a river tug before being subsequently dispatched via a round of machine-gun fire – but does the photo depict a genuine giant anaconda, or just a well-executed hoax involving forced perspective? The question remains unanswered.

Old Brazilian postcard from c.1932 depicting an alleged 40-45-m sucuriju gigante, or a clever example of forced perspective?

Old Brazilian postcard from c.1932 depicting an alleged 40-45-m sucuriju gigante, or a clever example of forced perspective?Equally enigmatic is this second photo, snapped in 1948, of a supposed 35-m (115-ft) sucuriju gigante, which reputedly came ashore and hid in the old fortifications of Fort Abuna in western Brazil's Guaporé Territory before being machine-gunned to death and pushed into the Abuna River.

Supposed 35-m-long sucuriju gigante floating dead in the Abuna River within Brazil's Guaporé Territory

Supposed 35-m-long sucuriju gigante floating dead in the Abuna River within Brazil's Guaporé TerritoryMore recently, on 19 August 1997, a veritable behemoth of a snake, jet-black and supposedly almost 40 m long, reputedly raided Nueva Tacna, a village near the Rio Napo in northern Peru. Its five eyewitnesses were later interviewed by no less eminent a person than Jorge Samuel Chávez Sibina, mayor of the Municipalidad Provincial de Maynas, who, in the company of radio journalist Carlos Villareal, flew over the village and afterwards stated that in his opinion: "There really is something to the villagers' stories". Moreover, a track supposedly left behind by this goliath measured about 488 m long and almost 10 m wide.

Fake, photoshopped online photograph of a supposed giant black anaconda

Fake, photoshopped online photograph of a supposed giant black anacondaPROPORTIONS AND PREHISTORY

How reliable are such reports as those presented here? Obviously, human estimation of size, especially when dealing with elongate, coiling objects like snakes, is far from perfect, and much given to exaggeration. Preserved skins do not provide reliable evidence for giant snakes either, because it has been ably demonstrated that those obtained from heavy snakes like anacondas can be deliberately stretched by as much as 30 per cent without causing much distortion to their markings.

Researchers have also suggested that their great size could cause giant snakes to experience problems in maintaining caudal blood pressure, and that they would need to remain submerged in water for their immense weight to be effectively buoyed. Furthermore, snake specialist Peter Pritchard has calculated that the maximum length of a snake species is 1.5-2.5 times its shortest adult length – which means that as small adult common anacondas measure 3-3.7 m long, the greatest theoretical length for this species is only marginally above 9 m.

Frontispiece to garrison deserter John Browne's Affecting Narrative book from 1802, depicting an 'ibibaboka' - clearly a grossly-exaggerated anaconda yet supposedly encountered by him in 1799 on St Helena!

Frontispiece to garrison deserter John Browne's Affecting Narrative book from 1802, depicting an 'ibibaboka' - clearly a grossly-exaggerated anaconda yet supposedly encountered by him in 1799 on St Helena!Even prehistory – a domain replete with reptilian giants - once offered little support for serpent monsters. Traditionally, the largest species of fossil snake on record has been North Africa's Gigantophis garstini, which existed approximately 40 million years ago and was believed to measure more than 10 m but not to exceed the minimum length needed to claim the Bronx Zoo's longstanding prize. And then along came Titanoboa.

All speculation concerning the impossibility (or at least the very considerable improbability) of giant snakes suffered a major blow in 2009, when scientists announced that 28 specimens of a hitherto-unknown fossil snake of truly gargantuan proportions had been discovered in the Cerrejón Formation within coal mines at La Guajira, Colombia.

Life-size model of Titanoboa at the Smithsonian Institution (© Smithsonian Institution)

Life-size model of Titanoboa at the Smithsonian Institution (© Smithsonian Institution)This new species, which existed 58-60 million years ago, was christened Titanoboa cerrejonensis. By comparing the sizes and shapes of the vertebrae of its eight largest specimens to those of modern-day snakes, researchers confidently estimated that the aptly-named Titanoboa had attained a maximum length of 12-15 m, weighed around 1135 kg, and boasted a girth of about 1 m at its body's thickest portion. Suddenly, giant snakes were a myth no longer – here was indisputable evidence that at least one such species had genuinely existed.

So could there be others too – still thriving in secluded swamps and rivers, their colossal forms in flagrant disregard of what should or should not be possible according to the laws of biophysics, lurking like primeval serpent dragons amid our planet's remotest, shadow-infested realms? Perhaps one day a future Fawcett will uncover the truth – provided, unlike Fawcett, he lives long enough to bring the required evidence back home with him!

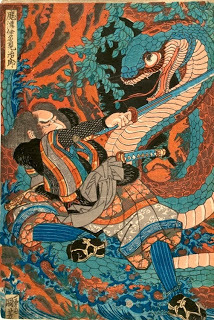

1825 print of warrior Matsui Tamijiro battling a giant snake (Utagawa Kuniyoshi)

1825 print of warrior Matsui Tamijiro battling a giant snake (Utagawa Kuniyoshi)

Published on September 19, 2013 19:06

September 16, 2013

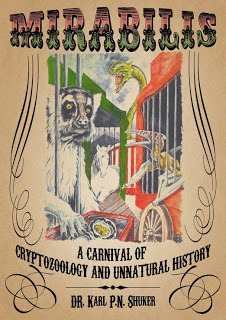

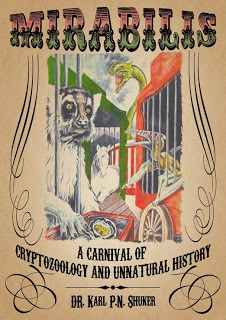

MAKING MY DEBUT ON 'COAST TO COAST AM' TO TALK ABOUT MY NEW BOOK 'MIRABILIS' AND CRYPTOZOOLOGY

Today, from 8 am to 10 am UK time, and from midnight to 2 am Pacific Time in the USA, I made my debut on the extremely popular North American radio talk show 'Coast To Coast AM' (click here for more details concerning my appearance), talking to Sundays host George Knapp concerning my new cryptozoology book Mirabilis and cryptozoology in general. I greatly enjoyed it and hope that you did too, but if you missed it you can listen to it in full here , on YouTube.

Published on September 16, 2013 14:19

September 9, 2013

LUMINESCENT BIRDS OF PARADISE IN BORNEO?

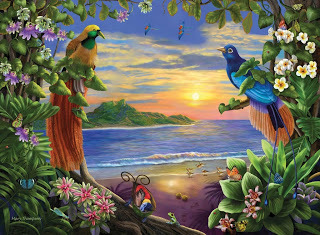

Luminescent fantasy birds (© Takaki)

Luminescent fantasy birds (© Takaki)On the morning of 5 September 2013, I was browsing through my newly-arrived copy of Flying Snake (vol. 2, #2; July 2013), a copy of which had been kindly sent to me by this periodical's founder/editor Richard Muirhead, when I came upon a very interesting article written by cryptozoology enthusiast Carl Marshall from the Stratford upon Avon Butterfly Farm documenting a visit to Malaysian Borneo by him and Butterfly Farm colleague Andrew Jackson during March 2013 in order to study its ecology and biodiversity.

Meeting Carl Marshall at the Stratford upon Avon Butterfly Farm on 2 June 2013 (Dr Karl Shuker)

Meeting Carl Marshall at the Stratford upon Avon Butterfly Farm on 2 June 2013 (Dr Karl Shuker)In his article, Carl listed several putative cryptids described to them by various inhabitants. Due to my longstanding interest in mystery birds, the entry in this list that attracted my especial interest was the following one:

"Luminous paradise type birds: We were informed by Matthew Lazenby of glowing paradise type birds in the deep forests of Ulu Kamanis."

Ulu Kamanis is situated in Sabah (formerly known as North Borneo), which is one of two Malaysian states present on the island of Borneo; Sarawak is the other one. Sandwiched between Sarawak and Sabah is the independent sultanate of Brunei, with all of the remainder of Borneo being part of Indonesia and generally referred to as Indonesian Borneo or Kalimantan.

By a most fortunate coincidence, Carl and I had already arranged to meet up during the afternoon of this very same day, 5 September, at his home just outside Stratford in order for me to collect the magnificent taxiderm specimen of a horned hare whose preparation he had very kindly arranged as a gift (click here for further details) – thanks Carl!

Carl Marshall (Dr Karl Shuker)

Carl Marshall (Dr Karl Shuker)Consequently, while visiting him there, I made a point of asking him whether he could supply me with any further details re Malaysian Borneo's luminescent birds of paradise, and he promised to email me the few details that he had obtained while out there.

True to his word, Carl duly sent me the following email two days ago:

"I thought I would send you a quick email about those luminous birds from Borneo with as much info as I can provide.

"They were described to me as fairly large birds that are are occasionally seen in forest clearings at Ulu Kamanis in Sabah. They are usually seen at dusk and appear not to be truly light emitting, but rather merely possessing a highly elaborate iridescent plumage.

"My theory is that these resplendent birds might be of the family Paradisaeidae, as during conversations with Matthew Lazenby (Jigger) an eye witness who lives in this area described these birds as matching very well with an unknown bird of paradise species.

"Our local guide Innus also reiterates these descriptions from his own experiences and agreed with my theory that these iridescent birds are possibly of this classification.

"I hope this is of interest."

Indeed it is – thanks again Carl!

Currently, 41 species of birds of paradise (family Paradisaeidae) are recognised by ornithologists, of which the vast majority are exclusive to the island of New Guinea or various smaller offlying ones. Two additional species (both belonging to the rifleman genus Ptiloris) are endemic to Australia, however, and a further two (the paradise crow Lycocorax pyrrhopterus and Wallace's standardwing Semioptera wallacii) are endemic to the Moluccas (Maluku) islands of Indonesia.

Two male and one female Wallace's standardwings, painted by Richard Bowdler Sharpe (1847-1909)

Two male and one female Wallace's standardwings, painted by Richard Bowdler Sharpe (1847-1909)As the Moluccas are separated from Sabah in the northernmost portion of Borneo only by the interposition of the Celebes Sea and from the remainder of Borneo only by the Indonesian island of Sulawesi (Celebes), it would not require too dramatic a stretch of zoogeographical imagination to conceive how a species of bird of paradise might exist in Borneo.

Nevertheless, until more precise details concerning their basic form and plumage can be obtained, the iridescent mystery birds of Ulu Kamanis cannot be assigned with any degree of certainty to Paradisaeidae, or indeed to any other avian family. But as Carl and Andrew plan to return to Sabah in 2014, we may not have too long to wait for such details to be forthcoming!

Birds of paradise - three known species depicted in a beautiful contemporary painting (© Mary Thompson)

Birds of paradise - three known species depicted in a beautiful contemporary painting (© Mary Thompson)

Published on September 09, 2013 15:34

September 5, 2013

HORNED HARES – A POTTED (OR SHOULD THAT BE JUGGED?) HISTORY!

st1\:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) }

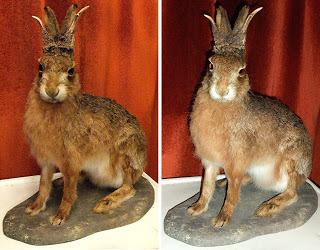

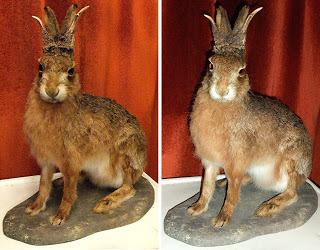

Two views, using different lighting effects, of my taxiderm horned hare (Dr Karl Shuker)

Two views, using different lighting effects, of my taxiderm horned hare (Dr Karl Shuker)

It is well known that one of North America's most popular legendary icons, the jackalope, originated in traditional lumberjack folklore but was first given a physical reality as recently as the 1930s when the earliest confirmed taxiderm specimen was artfully manufactured from a jack rabbit (technically a species of hare) and some pronghorn antelope horns by Douglas Herrick from Wyomimg, who was subsequently dubbed the 'Father of the Jackalopes'. Less well known, however, is that Europe also has a longstanding tradition of such creatures, but here they are termed horned hares.

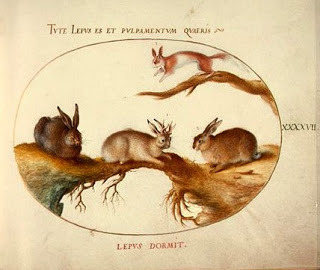

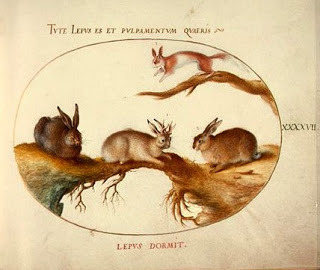

Selection of lagomorphs including horned hare (centre), portrayed in 1580 by Joris Hoefnagel in Plate 77 of Animalia Quadrupedia et Reptilia (Terra)

Selection of lagomorphs including horned hare (centre), portrayed in 1580 by Joris Hoefnagel in Plate 77 of Animalia Quadrupedia et Reptilia (Terra)

Today, I was delighted to receive as a very generous gift from friend and fellow crypto-enthusiast Carl Marshall a beautiful taxiderm specimen of a horned hare whose creation he had organised specially for me – thanks Carl!

Close up of my horned hare's head, highlighting its antlers (Dr Karl Shuker)

Close up of my horned hare's head, highlighting its antlers (Dr Karl Shuker)

So what better reason could I possibly require for presenting without further ado here on ShukerNature a potted (or even jugged!) history of the horned hare?

With my very own horned hare (Dr Karl Shuker)

With my very own horned hare (Dr Karl Shuker)

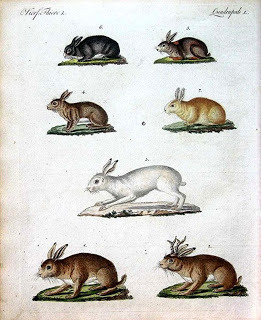

Until as recently as the late 18th Century, the authors of many of the early pre-scientific animal encyclopedias, or bestiaries as they were called then, still believed in the existence of fabulous beasts that nowadays have long been dismissed as non-existent fauna of folklore and legend - such as unicorns, dragons, satyrs, and mermaids. Another of these now-discounted creatures, far less dramatic than those listed above, yet no less intriguing, and often depicted in bestiaries, was the horned hare.

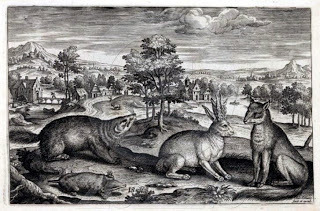

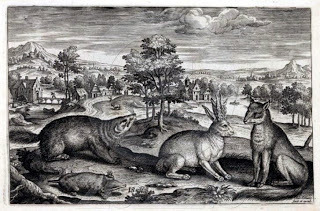

Engraving depicting a badger, mole, horned hare, and fox, from Adriaen Collaert's tome Animalium Quadrupedum (1612)

Engraving depicting a badger, mole, horned hare, and fox, from Adriaen Collaert's tome Animalium Quadrupedum (1612)

Despite its name, however, illustrations of this remarkable animal usually portrayed it as being much more rabbit-like than hare-like, and its 'horns' were in fact antlers, branched at their tips, and frequently very similar in overall appearance to those of young roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This bizarre mini-beast was widely reported across Europe, but was said to be particularly abundant amid the forests of Bavaria in Germany.

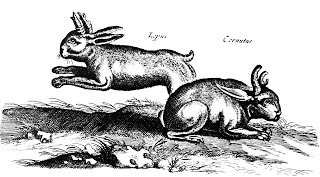

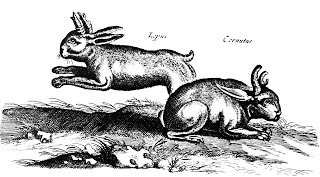

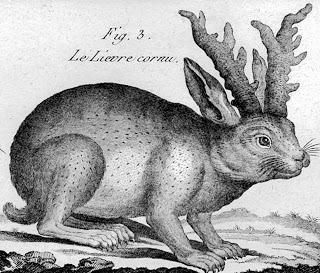

Horned hares engraving, from Theatrum Universale Omnium Animalium (1718)

Horned hares engraving, from Theatrum Universale Omnium Animalium (1718)

Indeed, its reality was so readily accepted by naturalists at that time that it even received its own formal Latin name – Lepus cornutus ('horned hare'). A number of highly-prized stuffed specimens also existed, usually proudly displayed in hunting lodges or in private collections of unusual natural history exhibits known as cabinets of curiosities.

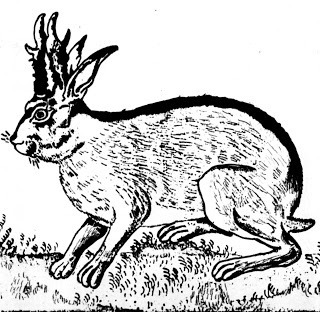

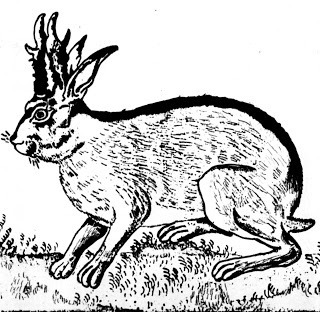

Horned hare engraving from the 16th Century

Horned hare engraving from the 16th Century

By the 19th Century, conversely, advances in zoological research and scientific knowledge had shown that the horned hare was not only a nonsense but a fraudulent one. Close examination of the taxiderm specimens revealed that they were hoaxes, created by the skilful manipulation of large stuffed rabbits or hares onto whose heads had been craftily grafted pairs of young, short deer antlers, or, more rarely, the trimmed, pointed horns of small African antelopes, particularly duikers.

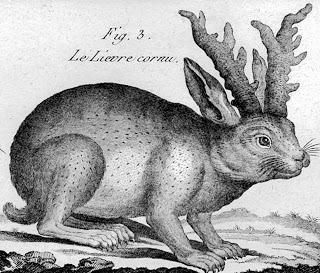

Horned hare engraving, from Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre's Tableau Encyclopedique et Methodique (1789)

Horned hare engraving, from Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre's Tableau Encyclopedique et Methodique (1789)

Yet even though its subject's authenticity had been disproved, the cult of the horned hare remained very much alive, so much so that by the mid-1800s a new craze had begun in earnest – the deliberate creation of ever more fanciful and exotic-looking horned hares, sporting not only antlers but even feathered wings, plus huge fangs startlingly similar to those of the prehistoric sabre-tooth tigers! In Bavaria, such incredible composites were referred to as wolpertingers, and were often created specifically as tourist attractions, or as souvenirs to tempt and fool wealthy but gullible visitors. Even today, they appear on t-shirts and postcards, and privately-owned specimens occasionally come up for sale in specialist auctions, where they invariably sell for very appreciable sums. The German Hunting and Fishing Museum at Munich houses a permanent exhibition of wolpertingers.

Two wolpertingers (Markus Bühler)

Two wolpertingers (Markus Bühler)

Equally bizarre is the rabbit-bird. Uniting the furry head of a rabbit with the feathered body of a bird, this highly unlikely hybrid was nonetheless firmly believed to be genuine by none other than the celebrated Roman naturalist-scholar Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD), who even documented it in his massive treatise Naturalis Historia - in which he claimed that it inhabited the lofty mountain peaks of the Alps. Needless to say, no such beast did, or does, exist – until 1918, that is.

Pliny's rabbit-bird (© Greyherbert/Flickr)

Pliny's rabbit-bird (© Greyherbert/Flickr)

For that was the year when Swedish taxidermist Rudolf Granberg created a stuffed hare with wings known as a skvader, deftly combining the head, foreparts, and limbs of a hare with the back, wings, and tail of a female capercaillie Tetrao urogallus – a very large species of grouse. Still exhibited today at the museum at Norra Berget in Sundsvall, eastern Sweden, it was inspired by an infamously far-fetched claim by hunter Håkan Dahlmark that he had shot just such a beast back in 1874 while hunting north of Sundsvall. Since then, other taxiderm skvaders have been created and, just like their Bavarian wolpertinger brethren, remain popular today.

The original taxiderm skvader at Norra Berget

The original taxiderm skvader at Norra Berget

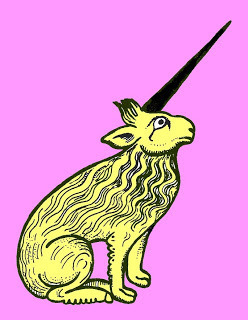

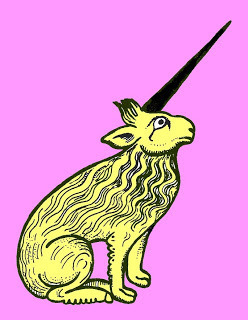

Nor should we forget the astonishing al-mi'raj or unicorn hare. According to a number of medieval bestiaries, this enigmatic creature resembled a large yellow hare, but its brow bore a single unicorn-like horn, black in colour. Said to inhabit a mysterious Indian Ocean island, and often featuring in Islamic poetry, this deceptive beast behaved in so placid and tame a manner that many a curious onlookers would approach it for a closer look – whereupon the al-mi'raj would suddenly lower its head and charge directly at its unsuspecting observer, fatally impaling him with its horn, then devouring him entirely!

13th-Century illustration of the al-mi'raj or unicorn hare

13th-Century illustration of the al-mi'raj or unicorn hare

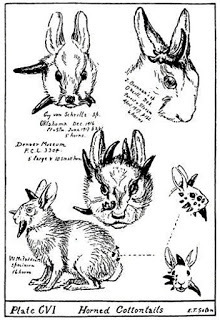

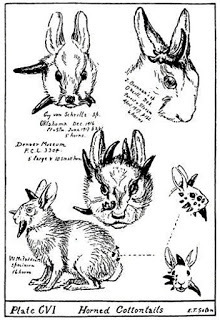

Is it possible, however, that Eurasia's horned hares and North America's jackalopes are not entirely the product of folklore and fakery but actually have at least a little basis in fact? The first strong evidence that this might indeed be true came in 1937, with the publication of Volume 4 of Canadian writer-naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton's book Lives of Game Animals. In the section discussing cottontail rabbits, Seton included a page of self-drawn sketches of rabbits bearing a grotesque array of horn-like protrusions from their heads and faces. Some of these recalled the bestiary illustrations of horned hares and the folktale descriptions of jackalopes.

Horned SPV-infected cottontail rabbits (Ernest Thompson Seton, 1937)

Horned SPV-infected cottontail rabbits (Ernest Thompson Seton, 1937)

But what had caused these freakish horns to develop? Studying cottontails inflicted in this manner, medical biologist Dr Richard E. Shope had discovered just a few years earlier that they had been infected by a specific virus (nowadays known as the Shope papilloma virus). This transforms facial follicle cells into hard tumours called papillomas, which in the most extreme cases give rise to these bizarre horns. One such specimen was found dead in a Minnesota woman's garden in September 2005 after she had called the police in alarm upon finding it there. In addition, there is a YouTube video of an even more recent living specimen.

Dr Shope also discovered a second virus that has similar effects, the Shope fibroma virus. Both are most common in North America. However, in Europe, hares are prone to a virus known as Leporipoxvirus, to which rabbits are also susceptible, and which again causes the production of horny facial nodules and growths.

The CFZ's North American jackalope (CFZ)

The CFZ's North American jackalope (CFZ)

It is easy to see how, centuries ago in pre-scientific times, if someone encountered a rabbit or hare in Eurasia or North America suffering from one of these viruses and bearing various horn-like growths on its head or face, belief in the existence of a rare, exotic species of horned hare or jackalope could swiftly develop. And as microbiological knowledge was at best inaccurate and at worst non-existent in those bygone ages, even naturalists might readily have been fooled into assuming that such horns were natural structures rather than the physical effects of a viral infection. Coupling this with the all-too-frequently exaggerated and distorted illustrations of animals present in bestiaries back then, and suddenly a hare with horns, or even a rabbit with antlers, is no longer so surprising and implausible a creature after all.

Coloured engraving of lagomorphs, including a horned hare at bottom right (original source unknown)

Coloured engraving of lagomorphs, including a horned hare at bottom right (original source unknown)

This ShukerNature blog post is an adapted excerpt from my latest book, Mirabilis:A Carnival of Cryptozoology and Unnatural History (Anomalist Books: New York, 2013).

Two views, using different lighting effects, of my taxiderm horned hare (Dr Karl Shuker)

Two views, using different lighting effects, of my taxiderm horned hare (Dr Karl Shuker)It is well known that one of North America's most popular legendary icons, the jackalope, originated in traditional lumberjack folklore but was first given a physical reality as recently as the 1930s when the earliest confirmed taxiderm specimen was artfully manufactured from a jack rabbit (technically a species of hare) and some pronghorn antelope horns by Douglas Herrick from Wyomimg, who was subsequently dubbed the 'Father of the Jackalopes'. Less well known, however, is that Europe also has a longstanding tradition of such creatures, but here they are termed horned hares.

Selection of lagomorphs including horned hare (centre), portrayed in 1580 by Joris Hoefnagel in Plate 77 of Animalia Quadrupedia et Reptilia (Terra)

Selection of lagomorphs including horned hare (centre), portrayed in 1580 by Joris Hoefnagel in Plate 77 of Animalia Quadrupedia et Reptilia (Terra)Today, I was delighted to receive as a very generous gift from friend and fellow crypto-enthusiast Carl Marshall a beautiful taxiderm specimen of a horned hare whose creation he had organised specially for me – thanks Carl!

Close up of my horned hare's head, highlighting its antlers (Dr Karl Shuker)

Close up of my horned hare's head, highlighting its antlers (Dr Karl Shuker) So what better reason could I possibly require for presenting without further ado here on ShukerNature a potted (or even jugged!) history of the horned hare?

With my very own horned hare (Dr Karl Shuker)

With my very own horned hare (Dr Karl Shuker)Until as recently as the late 18th Century, the authors of many of the early pre-scientific animal encyclopedias, or bestiaries as they were called then, still believed in the existence of fabulous beasts that nowadays have long been dismissed as non-existent fauna of folklore and legend - such as unicorns, dragons, satyrs, and mermaids. Another of these now-discounted creatures, far less dramatic than those listed above, yet no less intriguing, and often depicted in bestiaries, was the horned hare.

Engraving depicting a badger, mole, horned hare, and fox, from Adriaen Collaert's tome Animalium Quadrupedum (1612)

Engraving depicting a badger, mole, horned hare, and fox, from Adriaen Collaert's tome Animalium Quadrupedum (1612)Despite its name, however, illustrations of this remarkable animal usually portrayed it as being much more rabbit-like than hare-like, and its 'horns' were in fact antlers, branched at their tips, and frequently very similar in overall appearance to those of young roe deer Capreolus capreolus. This bizarre mini-beast was widely reported across Europe, but was said to be particularly abundant amid the forests of Bavaria in Germany.

Horned hares engraving, from Theatrum Universale Omnium Animalium (1718)

Horned hares engraving, from Theatrum Universale Omnium Animalium (1718)Indeed, its reality was so readily accepted by naturalists at that time that it even received its own formal Latin name – Lepus cornutus ('horned hare'). A number of highly-prized stuffed specimens also existed, usually proudly displayed in hunting lodges or in private collections of unusual natural history exhibits known as cabinets of curiosities.

Horned hare engraving from the 16th Century

Horned hare engraving from the 16th CenturyBy the 19th Century, conversely, advances in zoological research and scientific knowledge had shown that the horned hare was not only a nonsense but a fraudulent one. Close examination of the taxiderm specimens revealed that they were hoaxes, created by the skilful manipulation of large stuffed rabbits or hares onto whose heads had been craftily grafted pairs of young, short deer antlers, or, more rarely, the trimmed, pointed horns of small African antelopes, particularly duikers.

Horned hare engraving, from Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre's Tableau Encyclopedique et Methodique (1789)

Horned hare engraving, from Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre's Tableau Encyclopedique et Methodique (1789)Yet even though its subject's authenticity had been disproved, the cult of the horned hare remained very much alive, so much so that by the mid-1800s a new craze had begun in earnest – the deliberate creation of ever more fanciful and exotic-looking horned hares, sporting not only antlers but even feathered wings, plus huge fangs startlingly similar to those of the prehistoric sabre-tooth tigers! In Bavaria, such incredible composites were referred to as wolpertingers, and were often created specifically as tourist attractions, or as souvenirs to tempt and fool wealthy but gullible visitors. Even today, they appear on t-shirts and postcards, and privately-owned specimens occasionally come up for sale in specialist auctions, where they invariably sell for very appreciable sums. The German Hunting and Fishing Museum at Munich houses a permanent exhibition of wolpertingers.

Two wolpertingers (Markus Bühler)

Two wolpertingers (Markus Bühler)Equally bizarre is the rabbit-bird. Uniting the furry head of a rabbit with the feathered body of a bird, this highly unlikely hybrid was nonetheless firmly believed to be genuine by none other than the celebrated Roman naturalist-scholar Pliny the Elder (23-79 AD), who even documented it in his massive treatise Naturalis Historia - in which he claimed that it inhabited the lofty mountain peaks of the Alps. Needless to say, no such beast did, or does, exist – until 1918, that is.

Pliny's rabbit-bird (© Greyherbert/Flickr)

Pliny's rabbit-bird (© Greyherbert/Flickr)For that was the year when Swedish taxidermist Rudolf Granberg created a stuffed hare with wings known as a skvader, deftly combining the head, foreparts, and limbs of a hare with the back, wings, and tail of a female capercaillie Tetrao urogallus – a very large species of grouse. Still exhibited today at the museum at Norra Berget in Sundsvall, eastern Sweden, it was inspired by an infamously far-fetched claim by hunter Håkan Dahlmark that he had shot just such a beast back in 1874 while hunting north of Sundsvall. Since then, other taxiderm skvaders have been created and, just like their Bavarian wolpertinger brethren, remain popular today.

The original taxiderm skvader at Norra Berget

The original taxiderm skvader at Norra Berget Nor should we forget the astonishing al-mi'raj or unicorn hare. According to a number of medieval bestiaries, this enigmatic creature resembled a large yellow hare, but its brow bore a single unicorn-like horn, black in colour. Said to inhabit a mysterious Indian Ocean island, and often featuring in Islamic poetry, this deceptive beast behaved in so placid and tame a manner that many a curious onlookers would approach it for a closer look – whereupon the al-mi'raj would suddenly lower its head and charge directly at its unsuspecting observer, fatally impaling him with its horn, then devouring him entirely!

13th-Century illustration of the al-mi'raj or unicorn hare

13th-Century illustration of the al-mi'raj or unicorn hareIs it possible, however, that Eurasia's horned hares and North America's jackalopes are not entirely the product of folklore and fakery but actually have at least a little basis in fact? The first strong evidence that this might indeed be true came in 1937, with the publication of Volume 4 of Canadian writer-naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton's book Lives of Game Animals. In the section discussing cottontail rabbits, Seton included a page of self-drawn sketches of rabbits bearing a grotesque array of horn-like protrusions from their heads and faces. Some of these recalled the bestiary illustrations of horned hares and the folktale descriptions of jackalopes.

Horned SPV-infected cottontail rabbits (Ernest Thompson Seton, 1937)

Horned SPV-infected cottontail rabbits (Ernest Thompson Seton, 1937)But what had caused these freakish horns to develop? Studying cottontails inflicted in this manner, medical biologist Dr Richard E. Shope had discovered just a few years earlier that they had been infected by a specific virus (nowadays known as the Shope papilloma virus). This transforms facial follicle cells into hard tumours called papillomas, which in the most extreme cases give rise to these bizarre horns. One such specimen was found dead in a Minnesota woman's garden in September 2005 after she had called the police in alarm upon finding it there. In addition, there is a YouTube video of an even more recent living specimen.

Dr Shope also discovered a second virus that has similar effects, the Shope fibroma virus. Both are most common in North America. However, in Europe, hares are prone to a virus known as Leporipoxvirus, to which rabbits are also susceptible, and which again causes the production of horny facial nodules and growths.

The CFZ's North American jackalope (CFZ)

The CFZ's North American jackalope (CFZ)It is easy to see how, centuries ago in pre-scientific times, if someone encountered a rabbit or hare in Eurasia or North America suffering from one of these viruses and bearing various horn-like growths on its head or face, belief in the existence of a rare, exotic species of horned hare or jackalope could swiftly develop. And as microbiological knowledge was at best inaccurate and at worst non-existent in those bygone ages, even naturalists might readily have been fooled into assuming that such horns were natural structures rather than the physical effects of a viral infection. Coupling this with the all-too-frequently exaggerated and distorted illustrations of animals present in bestiaries back then, and suddenly a hare with horns, or even a rabbit with antlers, is no longer so surprising and implausible a creature after all.

Coloured engraving of lagomorphs, including a horned hare at bottom right (original source unknown)

Coloured engraving of lagomorphs, including a horned hare at bottom right (original source unknown)This ShukerNature blog post is an adapted excerpt from my latest book, Mirabilis:A Carnival of Cryptozoology and Unnatural History (Anomalist Books: New York, 2013).

Published on September 05, 2013 16:29

September 2, 2013

IN SEARCH OF THE ELUSIVE SCARLET VIPER

Computer-generated image of a scarlet viper (Dr Karl Shuker)

Computer-generated image of a scarlet viper (Dr Karl Shuker)It is well known that the common European adder or viper Vipera berus occasionally produces albinistic and melanistic individuals, due to the expression of certain mutant gene alleles. I was fortunate enough to see a bona fide black adder myself (and not of the Rowan Atkinson variety either!) when visiting Woody Bay, North Devon, back in 1993. Of course, these are not separate species, merely genetically-induced morphs of the common adder.

As recently as the mid-1800s, however, many natural history tomes were still soberly stating that Britain was also home to a much more remarkable, additional viperine form, one so distinct in fact that it was classed as a separate species in its own right – Vipera rubra, the scarlet viper. As its names suggest, this eyecatching serpent was bright red in colour, and was also said to be a little smaller than the normal adder. Yet it seemingly possessed a very limited geographical distribution, for according to a short Pet Reptiles article from 2001 by CFZ founder Jonathan Downes, it was only reported from certain parts of southern Dorset, particularly around Corfe Castle and Lulworth Cove.

In those specific areas, however, the scarlet viper was apparently a familiar sight, which makes it all the more surprising that by the end of the 19th Century it had vanished not only from such localities but also from the natural history literature. Suddenly, it was as if the scarlet viper had never existed – expunged even from the records as well as disappearing from life. Why?

A normal grey-coloured male adder

A normal grey-coloured male adderIt is not as if a scarlet viper would be such an unlikely, improbable herpetological entity. There is a genetically-inherited condition analogous to albinism and melanism that is known as erythrism, and individuals exhibiting it are abnormally red in colour. Erythristic iguanas, for instance, are bright orange-red instead of their normal green shade. Consequently, an erythristic common adder would make a very plausible scarlet viper. And as such colour morphs are often of only localised distribution due to genetic drift, this would also explain the scarlet viper's limited occurrence.

A normal brown-coloured female adder

A normal brown-coloured female adderWhereas the background colouration of normal male adders is grey, in normal female adders it is brown, but according to a number of sources that I've consulted, copper and even brick-red females have also been recorded. So as I have yet to uncover any eyewitness accounts of scarlet viper populations or even pairs of such snakes, another, even more plausible solution is that this mystery serpent species' distinctive colouration may have been due to a mutant sex-linked genetic aberration - meaning that the scarlet viper was based entirely upon sightings of abnormally red female adders. And indeed: within his book Reptiles and Amphibians in Britain (1983), part of the 'Collins New Naturalist Series', Deryk Frazer stated:

"The 'little red adder' of early herpetologists is a colour phase found in some juvenile females, which eventually become less distinctively coloured." Mystery solved? Very probably. Having said that: I cannot help but wonder whether any local museums or private collections of natural history specimens in southern Dorset unknowingly possess a preserved specimen or two of the scarlet viper. If any do, it would certainly be very interesting, not to mention extremely informative, to analyse DNA samples from them. After more than 150 years, we may then finally confirm categorically the precise zoological identity of this enigmatic British mystery snake.

A black adder (i.e. melanistic) and a normal adder (Guntram Deichsel)

A black adder (i.e. melanistic) and a normal adder (Guntram Deichsel)

Published on September 02, 2013 17:59

September 1, 2013

TWO SEA MONSTERS FOR THE PRICE OF ONE!

st1\:*{behavior:url(#ieooui) }

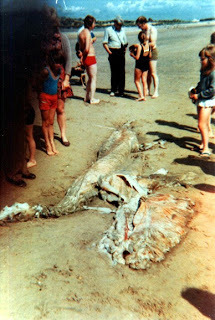

Photograph #1 - Kent sea monster carcase 1976, with pseudo-plesiosaur portion above mini-globster portion (Juliet Lilienthal)

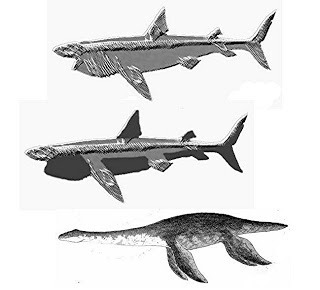

Photograph #1 - Kent sea monster carcase 1976, with pseudo-plesiosaur portion above mini-globster portion (Juliet Lilienthal)Sea monsters can be very deceiving, even when dead. For example, it is well known, especially in cryptozoological circles, that the decomposing carcase of a beached basking shark Cetorhinus maximus often transforms very dramatically, and deceptively, to yield what on first sight looks remarkably like a long-necked, four-flippered, slender-tailed, hairy plesiosaur-like creature. This is the so-called pseudo-plesiosaur effect, in which the jaw and sizeable gill apparatus fall away, revealing a lengthy portion of vertebral column that superficially resembles an elongate neck, coupled with the shark's dried-out pectoral and pelvic fins looking like flippers, its lower tail fin dropping off, and its skin's exposed collagenous connective fibres gaining the appearance of thick fur.

Similarly, when a sperm whale Physeter macrocephalus dies at sea and its carcase gradually rots, its heavy skull and skeleton eventually sink down to the ocean floor, but sometimes a very sizeable skin-sac of rotting blubber, surfaced externally with exposed connective tissue fibres, will remain afloat - encasing a thick matrix of collagen and often not only the substantial spermaceti organ too but also a few isolated ribs with fibrous flesh still attached. If subsequently washed ashore, becoming what is popularly dubbed a globster, this hairy, bulky gelatinous mass, with the ribs protruding like tentacles, is sometimes mistaken for the mortal remains of a gargantuan octopus – an extraordinary metamorphosis just as radical as the pseudo-plesiosaur effect, and one, therefore, that a few years ago I christened the quasi-octopus effect.