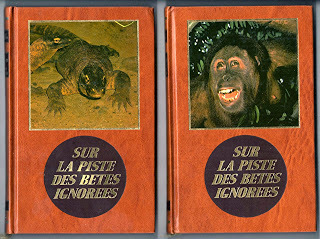

Karl Shuker's Blog, page 49

January 6, 2014

SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE SPECKLED BAND – AN UNKNOWN SPECIES OF REPTILE?

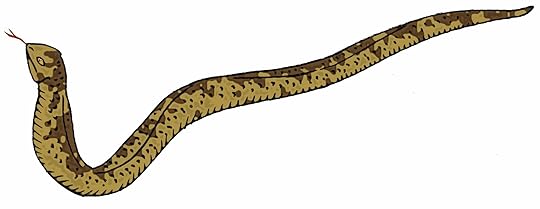

Reconstruction of the likely appearance of the Indian swamp adder, aka the speckled band (© Tim Morris)

Reconstruction of the likely appearance of the Indian swamp adder, aka the speckled band (© Tim Morris)According to a number of Sherlockian scholars, today, 6 January, is Sherlock Holmes's birthday - so it seemed a very appropriate day upon which to present the following ShukerNature investigation of mine.

During his numerous cases, the famous if fictitious consulting detective Sherlock Holmes, created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, encountered a number of extraordinary creatures – the hound of the Baskervilles, the giant rat of Sumatra (click here for my ShukerNature article re this monstrous rodent), an unknown species of worm that sent its observer insane, and an exceptionally venomous, enigmatic Indian serpent referred to obliquely by one of its victims as the speckled band. But does the latter snake truly exist, and, if so, what is it?

HOW SHERLOCK HOLMES DEFEATED THE SPECKLED BAND

First appearing in February 1892 within the Strand Magazine as a stand-alone Sherlock Holmes short story, 'The Adventure of the Speckled Band' is one of twelve that were then collected together and republished later that same year within a compilation volume entitled 'The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes'. (It was also adapted by Conan Doyle into a stage play called The Stonor Case, with the production opening at London’s Adelphi Theatre in June 1910.)

This particular story tells of how Dr Grimesby Roylott, a very aggressive medical doctor heavily in debt but with two heiress step-daughters, murdered one of them, Julia Stonor, using a most ingenious, undetectable modus operandi that he was now also secretly attempting to use upon his other step-daughter, Helen Stonor. If successful, he would retain all of their money. Although Helen does not realise that her own life is in imminent danger, she feels sufficiently disturbed by the mysterious death of her sister, who was heard to cry out "It was the band! The speckled band!" immediately before dying, to engage Sherlock Holmes to investigate.

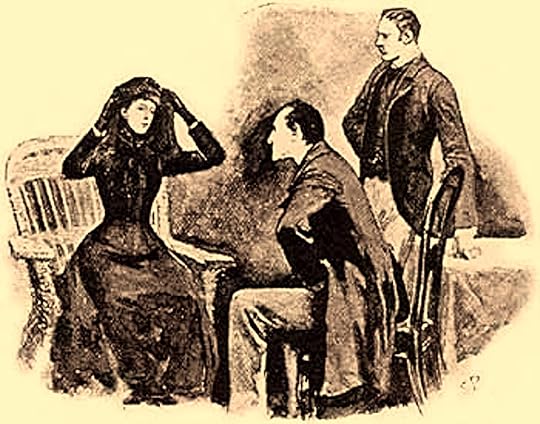

Holmes, Watson, and Helen Stonor, depicted by Sidney Paget

Holmes, Watson, and Helen Stonor, depicted by Sidney PagetAssisted by his faithful companion Dr Watson, it is Holmes who then discovers that Roylott had murdered Julia (and was now seeking to do the same to Helen) using an exceedingly venomous species of Indian snake referred to by Holmes as a swamp adder, whose blotch-patterned body was the speckled band that the doomed Julia's last words had succinctly described.

Sherlock Holmes striking out at the swamp adder, depicted by Sidney Paget

Sherlock Holmes striking out at the swamp adder, depicted by Sidney PagetHappily, after hiding in Helen's bedroom they are able to thwart the deadly serpent, which, angered by Holmes's attack upon it with a cane, swiftly flees from whence it had come - back into the bedroom of its owner, Roylott. When Holmes and Watson then enter Roylott's room, they find him dead, with what looks at first like a speckled band wrapped around his head. Upon cautious, closer inspection, however, this proves to be the swamp adder, which in its enraged, still-agitated state had turned upon Roylott, killing him with a single lethal, fast-acting bite.

Waxwork of Dr Grimesby Roylott with swamp adder around his head, at London's Sherlock Holmes Museum (public domain, from Wikipedia)

Waxwork of Dr Grimesby Roylott with swamp adder around his head, at London's Sherlock Holmes Museum (public domain, from Wikipedia)THE INDIAN SWAMP ADDER – IN SEARCH OF AN IDENTITY

In the story, the swamp adder was referred to by Holmes as "the deadliest snake in India", but what exactly is a swamp adder? No known species of snake in India – or anywhere else, for that matter - is ever referred to by that particular name. Unfortunately, however, the story contains only the sparsest of morphological and behavioural details concerning this enigmatic serpent.

Its body is yellow, patterned with brownish speckles, and probably around 1 m long but fairly slender if it resembles a band and can wrap itself around a man's head. Its own head is squat and diamond-shaped, and its neck is puffed. Its hiss is said to be "a very gentle, soothing sound, like that of a small jet of steam escaping continually from a kettle", but according to Holmes its venom is so toxic that it kills in 10 seconds. Yet its fangs apparently leave such tiny, inconspicuous puncture wounds when it bites its victim that they were not noticed by the coroner who examined Jane Stonor's body. For according to a statement made by her sister Helen to Holmes, no marks had been found upon Jane by the coroner.

Down through the years, this intriguing reptilian mystery has engaged the attention of many scholars, of Sherlockian and herpetological expertise alike, with a number of different identities proposed for the perplexing Indian swamp adder.

IS THE SWAMP ADDER TRULY A SPECIES OF VIPER?

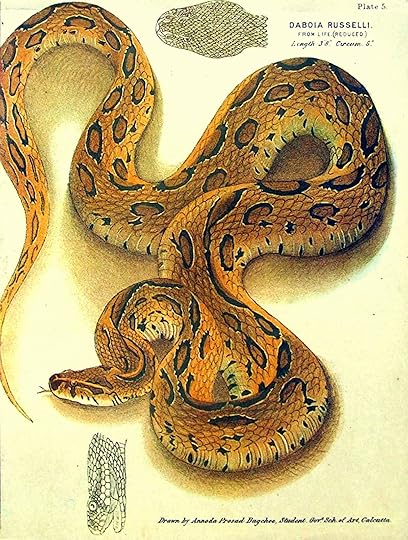

The most popular identity is the very venomous tic polonga or Russell's viper Daboia russelii, a large terrestrial species found throughout the Indian subcontinent. Due in no small way to its frequent proximity to human habitation, this infamous species is responsible for more deaths and incidents involving snake-bite than any other venomous snake in the entire region. Up to 1.66 m long, its relatively slender, brown-blotched, yellow-tan body does recall the 'speckled band' description for the mystifying swamp adder. Also, as its triangular head is distinct from its neck, when viewed at certain angles its head and the beginning of its neck can collectively yield a diamond shape.

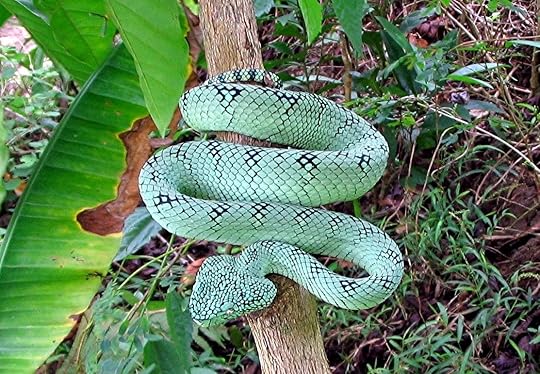

Russell's viper (© gupt_sumeet/Wikipedia)

Russell's viper (© gupt_sumeet/Wikipedia)However, like that of all vipers, this species' venom is haemotoxic, which is relatively slow-acting compared to the much more rapid-acting neurotoxin produced by elapids. And far from being gentle and soothing in sound, its hiss is famously loud – among the loudest hisses produced by any species of snake. In addition, its preferred habit is dry, grassy, open terrain; it actively avoids humid, swampy, marshy areas. Clearly, therefore, the Russell's viper is unlikely ever to be referred to as a swamp adder.

Saw-scaled viper depicted in a painting from 1878

Saw-scaled viper depicted in a painting from 1878Two other viperid candidates that have also been proposed on occasion are the Indian saw-scaled viper Echis carinatus (also known as the little Indian viper) and the temple viper Tropidolaemus wagleri. However, the former species does not exceed 80 cm (and only rarely exceeds 60 cm), and does not possess either the speckled patterning or the diamond-shaped head of the swamp viper. Also, it is an inhabitant of dry, rocky terrain, not humid swamps. As for the temple viper: this pit viper species is bigger than the saw-scaled viper, with females growing up to 1 m long. It also exhibits a range of colour and pattern variations, but none of them includes that of the swamp adder. And, crucially, it is not native to India anyway (its distribution being confined to southeastern Asia).

Temple viper, green variety (© Bonvallite/Wikipedia)

Temple viper, green variety (© Bonvallite/Wikipedia)Neither is the African puff adder Bitis arietans, yet this too has been suggested by some as a putative swamp adder. Quite apart from its fundamental zoogeographical difference, however, the puff adder is renowned for the loudness (as opposed to the gentleness) of its hiss, and for the savagery of its bite, whose fangs can cause severe physical trauma in addition to their envenoming effects. This is a very far cry from the very inconspicuous puncture marks attributed to the swamp adder.

Puff adder ready to strike

Puff adder ready to strikeAnother exclusively African species that has been considered is the rhinoceros viper Bitis nasicornis, named after its instantly noticeable horn-like scales on the end of its nose – features conspicuous only by their absence in the swamp adder's description!

Rhinoceros viper (© Dawson/Wikipedia)

Rhinoceros viper (© Dawson/Wikipedia)Exit the puff adder and the rhinoceros viper.

COBRAS, BOAS, AND OTHER UNLIKELY SWAMP ADDER EXPLANATIONS

The common Indian cobra Naja naja is a much-touted elapid candidate for the swamp adder's identity, particularly by the late Richard Lancelyn Green and certain other Sherlockian scholars and devotees. Certainly, its neurotoxin would act more swiftly than the haemotoxin of any viper or adder. Nevertheless, it is difficult to conceive how so familiar and distinctive a snake as this one, perhaps the best known serpent species in all of India, could possibly be one and the same as the mysterious swamp adder. True, the latter's puffed neck may be an allusion to the cobra's hood (or at least a cobra-reminiscent neck expansion), but the Indian cobra lacks the characteristic speckled patterning of the swamp adder, and its head is not diamond-shaped. In fact, it looks nothing remotely like any type of adder or viper.

Indian cobras and snake charmers, depicted in a lithograph from 1890

Indian cobras and snake charmers, depicted in a lithograph from 1890Even more implausible ophidian identities that have been raised at one time or another include the decidedly non-venomous, non-Asian boa constrictor Boa constrictor; the extremely venomous but irrefutably Australian taipan Oxyuranus scutellatus; and a species of krait.

Fundamental zoogeographical differences aside, the boa constrictor notion no doubt stems from a suggestion that Conan Doyle was inspired to write his story having read a story entitled 'Called on by a Boa Constrictor: A West African Adventure', which had appeared in Cassell’s Saturday Journal, published in February 1891. Staying in a ramshackle cabin belonging to a Portuguese trader, the narrator reveals his horror at being woken by a massive snake dangling over him. Paralysed by fear, he cannot cry out, but he spots a bell hanging off a beam within reach. Although the cord to ring it has rotted away, the narrator discloses how he manages to summon help by hitting it with a stick.

Boa constrictor

Boa constrictorNor is this the only link between the speckled band mystery and a species of constricting snake. In his stage production of this story, The Stonor Case, Conan Doyle cast an African rock python Python sebae as the speckled band. Unfortunately, this particular snake did not excel in the role. Conan Doyle later wrote:

"We had a fine rock boa [sic] to play the title-rôle, a snake which was the pride of my heart, so one can imagine my disgust when I saw that one critic ended his disparaging review by the words, "The crisis of the play was produced by the appearance of a palpably artificial serpent." I was inclined to offer him a goodly sum if he would undertake to go to bed with it."

As for a krait: it is true that certain species are Indian, all are venomous (some extremely so), and they may be encountered in damp areas. However, they differ dramatically from the speckle-patterned swamp adder with its squat diamond-shaped head by virtue of their boldly striped markings and their sleek, slender head.

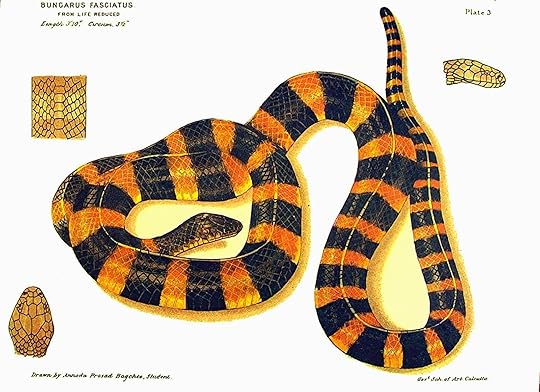

Banded krait, depicted in a painting from 1878

Banded krait, depicted in a painting from 1878Kraits are also extremely timid, often preferring to conceal their head amid their coils, drawing attention away from it by vigorously twitching their tail instead, thus readily contrasting with the swamp adder's active, undisguised aggression.

Of course, there is the remote, but not impossible, prospect that the swamp adder is not a snake at all...

WHEN IS A SNAKE NOT A SNAKE? WHEN IT'S A LEGLESS LIZARD?

Certainly, there are various peculiar behavioural characteristics claimed for the swamp adder that cause problems when attempting to reconcile it with any species of snake. In 'The Adventure of the Speckled Band', the swamp adder reaches its victim, Julia Stonor, by crawling through a ventilation shaft linking her bedroom with that of her murderous step-father Roylott next door, and then down a rope pull hanging directly over the bed in which she is sleeping. After it has bitten her, the snake crawls up the rope again and back through the shaft, in response to Roylott (in his bedroom) having alerted it by whistling to it!

First and foremost: unless it were an exceptionally adept arboreal species, would the swamp adder be able to climb up a vertical length of rope? And secondly: as snakes are famously insensitive aurally to airborne vibrations, how could it possibly be able to hear Roylott's whistling?

Consequently, there has been speculation that the swamp adder is not a snake at all, but conceivably a legless or near-legless species of lizard, belonging to the skink family. There are indeed several species of skink fitting this description, and which therefore do appear remarkably serpentine on first glance, especially to non-specialist observers. Some such lizards, moreover are native to India.

Chalcides chalcides

, a near-limbless skink

Chalcides chalcides

, a near-limbless skinkAnd skinks, unlike snakes, can definitely hear airborne vibrations. Whether they are adept at climbing up and down vertical ropes is another matter, but in any case this otherwise ingenious non-ophidian identity is fatally scuppered by the incontestable fact that skinks are entirely non-venomous. Consequently, if a skink bit someone, they would not be poisoned by it.

The only sensible conclusion that can be drawn from this article's analysis of the varied candidates on offer is that the swamp adder is an entirely fictitious, invented creature that Conan Doyle created specifically in order to supply his story with a supremely formidable reptilian opponent for pitting against Sherlock Holmes – an ophidian Moriarty, no less. Aspects of its appearance may well have been inspired by real snakes, such as the Russell's viper's body colouration and markings, and the rapid action of the cobra's neurotoxin, but the swamp adder has no basis in reality as a valid, discrete species in its own right.

Russell's viper, depicted in a drawing from 1878

Russell's viper, depicted in a drawing from 1878However, this is not quite the end of this literary serpent's identity crisis. There is still one more identity to consider, the most astonishing of all – not only because of its particular nature but also because of where (and how) it appeared within the scientific literature.

SWAMP ADDER AND MONGOLIAN DEATH WORM – ONE AND THE SAME CREATURE?

In a previous ShukerNature article (click here ), I documented an extraordinary mystery beast said to inhabit the Gobi Desert and known as the Mongolian death worm. According to the nomads inhabiting this vast expanse of sand, the death worm can spit forth a deadly, corrosive venom, and can also kill instantly if touched by a mechanism that sounds uncannily like electrocution. No specimen of this reputedly lethal animal has ever been made available for scientific analysis, and it may well simply be folkloric, or even if genuine merely a harmless amphisbaenian or similar reptile whose murderous talents owe more to local superstition than to physiological capability.

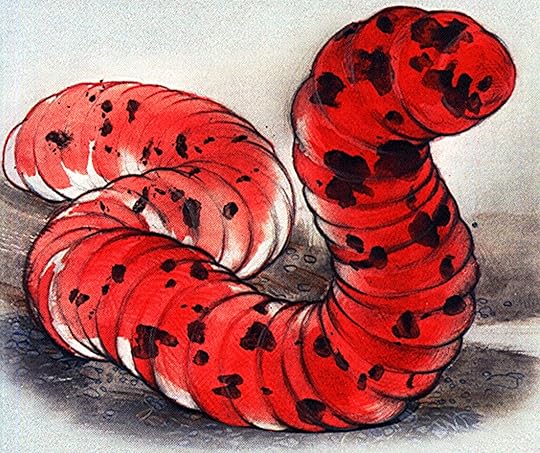

Reconstruction of the likely appearance of the Mongolian death worm (© Ivan Mackerle)

Reconstruction of the likely appearance of the Mongolian death worm (© Ivan Mackerle)In 1956, however, the death worm was sensationally linked to the swamp adder as the latter's bona fide identity. Not only that, it was even given a formal scientific name. The publication in which all of this appeared was a very comprehensive 238-page monograph of the lizard family Helodermatidae, which houses those two famously venomous New World species, the Gila monster Heloderma suspectum and the beaded lizard H. horridum. Published in no less august a scientific journal than the Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, and entitled 'The Gila Monster and Its Allies', it was authored by renowned herpetologists Drs Charles M. Bogert and Rafael Martín Del Campo, and as would be expected from such authors writing in such a journal, the paper was totally scientific and serious throughout – or was it?

Gila monster

Gila monsterTucked away on pages 206-209, in a section entitled 'Hybrid Origin', was a mind-boggling claim that according to a paper by snake authority Dr Laurence M. Klauber, a hybrid creature had been successfully produced in a laboratory in Calcutta, India, by crossbreeding cobras with Gila monsters! Not only that, some of these astounding hybrids had subsequently escaped, with various of their descendants yielding the allegedly highly venomous Indian lizard called the bis-cobra (featured in a forthcoming book of mine), and other descendants yielding the Mongolian death worm in the Gobi Desert!

Moreover, and equally dramatic, this selfsame hybrid was also claimed to be the identity of the swamp adder in Conan Doyle's Speckled Band story. A quadrupedal lizard with the venomous potency of a cobra would, in the opinion of Klauber, reconcile all of the problems faced when attempting to identify the swamp adder with any of the more traditional identities that have been proposed.

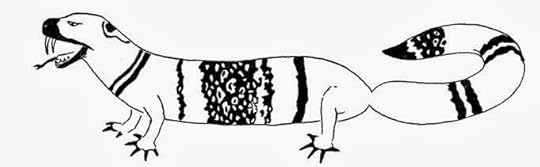

Accordingly, in their monograph Bogert and Martín Del Campo put forward an official binomial name for this hybrid, which was clearly now breeding true and therefore, they felt, fully deserved one. They dubbed it Sampoderma allergorhaihorhai – 'Sampoderma' combining 'samp' (a Hindustani name for 'snake') and the Gila monster's generic name, Heloderma; and 'allergorhaihorhai' being a name applied by the Gobi nomads to the death worm. They even included an ideogram of the hybrid's appearance.

Ideogram of Sampoderma allergorhaihorhai (© Derry Bogert/Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History)

Ideogram of Sampoderma allergorhaihorhai (© Derry Bogert/Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History)Needless to say, however, the concept of successful hybridisation between a cobra and a Gila monster is so outlandish that there was clearly more – or less – to the claims of Bogert and Martín Del Campo than met the eye, as a closer study of this particular section of their monograph soon revealed. (Moreover, the bis-cobra is also a red herring, figuratively if not taxonomically, because in reality it is a harmless varanid that superstitious folklore has conferred all manner of venomous traits upon.) For although Klauber was indeed a real-life herpetological authority and his paper regarding the hybrid also existed, it had not been published in any scientific journal but instead within an issue from 1948 of the Baker Street Journal.

This was a periodical devoted entirely to the fictional world contained within the stories of Sherlock Holmes, and included much imaginative and entertaining but entirely theoretical speculation and extrapolation regarding various aspects of these stories' plots, characters, etc. And indeed, in his paper Klauber refers to Holmes, Watson, and the nefarious Dr Roylott as real persons, naming Roylott as the creator of the cobra x Gila monster hybrid. In short, it was all entirely tongue-in-cheek, not to be taken in any way seriously.

As this is instantly apparent from reading Klauber's paper, why, therefore, had Bogert and Martín Del Campo included the fictitious hybrid in a sober, ostensibly factual manner within their otherwise entirely literal, highly authoritative monograph? According to Daniel D. Beck writing in his own major work, Biology of Gila Monsters and Beaded Lizards (2004), it was a prank by Bogert that was meant to poke fun at one of his "stodgy" colleagues at the American Museum of Natural History.

Beaded lizards – closest living relative of the Gila monster

Beaded lizards – closest living relative of the Gila monsterWhatever the reason, there is no doubt at all that equating it even in jest with the Mongolian death worm yielded for the dreaded Indian swamp adder (aka the speckled band) an identity so extraordinary that even the great Sherlock Holmes himself may well have been hard-pressed to deduce it!

Sherlock Holmes, depicted by Sidney Paget

Sherlock Holmes, depicted by Sidney PagetNB - all non-credited illustrations included in this ShukerNature article are (to the best of my knowledge) in the public domain.

Published on January 06, 2014 05:30

January 2, 2014

FLORES HOBBITS AND THE GIANT STORK OF DOOM

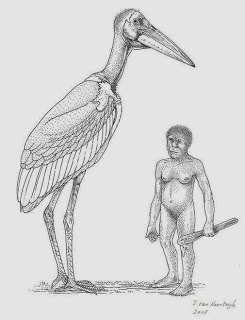

Homo floresiensis

vs Leptoptilos robustus (© Hodari Nandu/deviantart)

Homo floresiensis

vs Leptoptilos robustus (© Hodari Nandu/deviantart) I am extremely fortunate to count among my friends and colleagues a number of extremely talented artists, and the pseudonymous 'Hodari Nandu' (aka 'Justin Case') is one of these very gifted persons, as immediately demonstrated by the particularly vibrant example of his artwork presented above (click it to enlarge it), which showcases two most remarkable island-confined species.

Where on Earth would you find all within the very selfsame location a unique, Alice-in-Wonderland-reminiscent assemblage of mega-rats and mini-humans, gargantuan lizards, dwarf elephants, and gigantic storks? Only on Flores – a small island in Indonesia's Lesser Sundas group that provides some classic examples of both island gigantism and insular dwarfism.

Between 20,000 and 10,000 years ago, it was home to: two extra-large species of giant rat, Papagomys armandvillei and P. theodorverhoeveni, the former of which still survives today (and indeed, according to some researchers the latter may do too); a dwarf subspecies of elephant-related stegodont proboscidean Stegodon florensis insularis, which died out around 12,000 years ago and is the youngest stegodont form on record from southeast Asia; the Komodo dragon Varanus komodoensis, the world's largest living species of lizard, which still survives on Flores today (as well as on the neighbouring islands of Komodo, Rintja, and Padar) and undoubtedly preyed upon Flores's dwarf stegodonts; plus the two highly significant species featured in this ShukerNature article's opening illustration.

If it can't see me, it can't eat me, right? Wrong! Never under-estimate its very highly-developed sense of smell! Posing with a life-sized Komodo dragon model at Chester Zoo, England (© Dr Karl Shuker)

If it can't see me, it can't eat me, right? Wrong! Never under-estimate its very highly-developed sense of smell! Posing with a life-sized Komodo dragon model at Chester Zoo, England (© Dr Karl Shuker)One of these is the now world-famous 'hobbit' – the informal nickname given to Flores Man Homo floresiensis. With its most complete recorded specimen estimated at approximately 18,000 years old, this controversial, diminutive species of hominid apparently stood little more than 3 ft tall, may be descended from Homo erectus, and is believed to represent another case of insular dwarfism. Its first scientifically-documented remains were discovered in September 2004 at Liang Bua Cave in western Flores.

Life-size replicas of Homo erectusand Homo floresiensis skulls for comparison purposes (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Life-size replicas of Homo erectusand Homo floresiensis skulls for comparison purposes (© Dr Karl Shuker)And the other species, whose remains were also uncovered in that very same cave, may have been one of the Flores hobbits' deadliest antagonists. It is a marabou stork, but far bigger than any of today's trio of marabou species. Yet it remained undescribed by science until as recently as 2010. Formally dubbed Leptoptilos robustus, the giant stork of Flores stood approximately 6 ft tall and weighed up to 35 lb, due to its extremely heavy leg bones – on account of which it is likely to have been predominantly if not exclusively flightless.

Even so, Smithsonian Institution palaeontologist Dr Hanneke J.M. Meijer and Dr Rokus A. Due from Jakarta's National Center for Archaeology, who jointly described its fossilised remains (dated at between 20,000 and 50,000 years old) in a Zoological Journal of the Linnean Societypaper, believe that it was still theoretically capable of hunting and devouring juvenile hobbits. Having said that, there is presently no direct evidence confirming such activity; in the words of Dr Meijer as spoken during a 2010 interview with the UK's BBC television news service: "Whether or not this animal may have eaten hobbits is speculative: there is no evidence for that." Then again, as Dr Meijer also conceded in that same interview: "But can not be excluded either."

In European tradition, the stork brings newborn human babies to their parents - but in a major reversal of that benevolent role, Indonesia's giant stork of doom may conceivably have hunted down such babies (possibly even older infants too) and devoured them. Only on the topsy-turvy island of Flores!

Were the hobbits of Flores stalked by a stork? (© Inge van Noortwijk)

Were the hobbits of Flores stalked by a stork? (© Inge van Noortwijk)

Published on January 02, 2014 17:44

January 1, 2014

TRILOBITE BEETLES. CETI EELS, AND THE BEAST OF BRUNEI

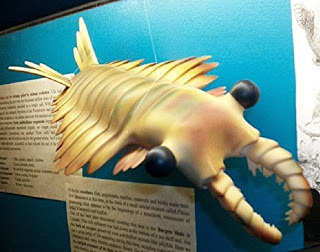

The mystifying Beast of Brunei (© Hazwan)

The mystifying Beast of Brunei (© Hazwan)Where else but on the internet are you ever likely to encounter a creature as bizarre in appearance as the specimen depicted in the above photograph – unless, that is, it turned up in a river located within the Sultanate of Brunei? This small independent sovereign state situated in northwestern Borneo tends to be more famous for its extensive petroleum and gas fields and its mega-wealthy ruler, one of the world's richest men, than for any freshwater cryptids. All of that may change, however, if this ShukerNature post's mystery beast is ever confirmed to be genuine – but is it?

I first learned of the entity that I have herewith dubbed the Beast of Brunei on 14 December 2013, when fellow British cryptozoological researcher Richard Muirhead placed on the wall of the Facebook Cryptozoology Group a clickable link to a page (at http://www.projectnoah.org/spottings/124556003) that he had spotted earlier on the website of Project Noah. This website encourages persons to upload photos of any animal whose taxonomic identity they wish to discover. On the page spotted by Richard was the photograph that heads this current ShukerNature article, together with only the briefest, single-line account by the person who had posted the photo there, and who is based in Brunei. The person's user name is Hazwan (but no real name or biographical details are present), who claimed: "Someone caught this during fishing", and then asked what it was. Hazwan also claimed that the photo had been obtained on 11 December, and had been posted by him/her that same day on this Project Noah page. In addition, Hazwan stated that the coordinates of the location where the creature had been photographed were Lat: 4.97 Long: 114.90. This is near the coast within Brunei's capital, Bandar Seri Begawan.

The armoured anomaly present inside what looked like a white bucket or similar vessel containing some yellowish water was certainly very unfamiliar in appearance, and the lack of anything in the photograph that could provide a scale to gauge its size only served to heighten the mystery surrounding it. On first sight, it looked like some bizarre form of crustacean, but it seems to lack the sizeable number of limbs and dual pair of antennae typically associated with these arthropods. Also, the pincer-like cerci seemingly present at the posterior end of its body were much more reminiscent of the abdominal forceps of earwigs and certain other insects than of anything exhibited by a crustacean. Yet I am not familiar with any form of aquatic insect – adult or larval stage - that is even vaguely similar in appearance to the Beast of Brunei.

Beast of Brunei on left (© Hazwan), and a female Duliticolahoiseni trilobite beetle from Malaysia on right (© Yixiong Cai = Tiomanese/Flickr)

Beast of Brunei on left (© Hazwan), and a female Duliticolahoiseni trilobite beetle from Malaysia on right (© Yixiong Cai = Tiomanese/Flickr)Could it therefore have been some form of terrestrial insect that had inadvertently fallen into the river and had then been spied and caught by whoever had photographed it? As it so happens, there is a group of terrestrial beetles that do offer at least a superficial resemblance to this mystery animal. Coleopterans belonging to the taxonomic family Lycidae, they are known, for good reason, as trilobite beetles. For whereas the adult males are typical-looking beetles (and also fairly small, only around 1 cm long), the much larger adult females (up to 6 cm long) and also the juveniles sport an ornate protective armour of segmented, spine-bearing plates known as scutes that do recall the appearance of those long-vanished prehistoric arthropods the trilobites – and also the Beast of Brunei, as seen in the comparison photograph above.

Yet despite spending a considerable time perusing images online of various species of trilobite beetle (insects, incidentally, that do include Borneo within their distribution range), I have failed to find any that provide a convincing correspondence to the Beast of Brunei. Possibly the closest are those of the genus Duliticola (which is actually named after Borneo's Mount Dulit), but the Beast's body is proportionately too long and slender, and its cerci are unprecedented among trilobite beetles.

A still from a YouTube video showing an exceptionally attractive, lilac-hued female trilobite beetle from Puhipii Mountain in Oudomxay Province, northwestern Laos, uploaded onto YouTube on 13 January 2009 (© Quaoar Power/YouTube)

A still from a YouTube video showing an exceptionally attractive, lilac-hued female trilobite beetle from Puhipii Mountain in Oudomxay Province, northwestern Laos, uploaded onto YouTube on 13 January 2009 (© Quaoar Power/YouTube)By today, 1 January 2014, the Project Noah page containing Hazwan's Beast photograph had attracted 20 comments from various readers, asking questions concerning the creature and offering some suggestions as to its possible identity, with a possible Duliticola larva being favoured, albeit very hesitatingly, by more than one person. In response, however, Hazwan had merely added that it was a friend (unnamed) who had photographed the animal, that it had been caught in a Brunei river, but that he/she had no further information or photos relating to it. One reader boldly suggested that the creature could be some form of anomalocarid – but as pointed out by Richard S. White (director of the International Wildlife Museum in Tucson, Arizona), those armoured stem arthropods became extinct at least 400 million years ago, at least as far as the fossil record is concerned. Moreover, all known forms were exclusively marine.

As for the true trilobites: the last of these iconic if similarly archaic marine arthropods had died out during the mass extinction at the end of the Permian Period, approximately 250 million years ago.

Classic early illustration of trilobites by Heinrich Harder

Classic early illustration of trilobites by Heinrich HarderIt was strange, but from the first moment that I saw Hazwan's photograph, I felt sure that I'd seen something like the Beast of Brunei somewhere before - but where? On 14 December, I'd reposted its photo and Project Noah link from Richard's Facebook wall onto my own, and asked for opinions. Some FB colleagues shared my view that it was vaguely reminiscent of a trilobite beetle, and there was also some discussion as to whether it might actually be a man-made fishing lure, whose jointed body would presumably wriggle in an animate manner in the river's current and thus attract fishes to it.

However, the comments that intrigued me the most were those of Kristian Lander, Blake Smith, and Jonathon Richter, all three of whom independently called to attention its similarity to a small but hideous, much-dreaded creature from science fiction – the ear-penetrating, mind-controlling Ceti eel, which appeared in the second Star Trek movie, The Wrath of Khan, released by Paramount Pictures in 1982. Having seen this film, and at around that time, I now realised that it was a dimly-recollected memory of the Ceti eel that I'd been thinking of when I'd felt certain I'd seen something like the Beast of Brunei before.

The Ceti eel's principal attributes are summarised as follows in its Wikipedia entry:

The Ceti eel appears in the 1982 film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. It is the only indigenous lifeform of Ceti Alpha V known to have survived after Ceti Alpha VI exploded and sent Ceti Alpha V into a different orbit. Ceti eels incubate their larvae between protective plates that line their backs. The slime-covered larva will seek out a larger animal, enter its skull through the ear and wrap itself around the cerebral cortex. This causes the subject intense pain and makes them very susceptible to suggestion. As the larva grows, the host suffers from insanity and eventual death. Ceti eels bear a remarkable resemblance to antlion larvae.

Although I would argue against it bearing "a remarkable resemblance" to antlion larvae, this fictitious creature does provide a certain degree of accord with the Beast of Brunei, as revealed by the following photo of an official Ceti worm prop used for the Star Trek film in question:

An official Ceti eel prop from

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan

(© startrekpropauthority.com/Paramount Pictures)

An official Ceti eel prop from

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan

(© startrekpropauthority.com/Paramount Pictures)Even so, it still didn't match the elusive image that I had in my mind – but then, when perusing further illustrations of the Ceti eel online, I finally found it!

I discovered that the version of the Ceti eel seen on screen was not the only one that had been conceived. No less than 15 different concept or prototype Ceti eels had been sketched by one of the film's designers, visual-effects artist Ken Ralston from Industrial Light & Magic, yielding a great diversity of forms, and it was the film's producer, Robert S. Sallin, who had made the final choice as to which of these should become the on-screen Ceti eel. Of the 14 versions that didn't make it, one of them (Ceti eel Concept #11) even possessed a pair of sizeable, grasshopper-like hind legs; and another one, the very first to be sketched by Ralston in fact (Ceti eel Concept #1), sported a pair of posterior earwig-like cerci!

Yes indeed, there it was – the image that I knew I'd seen somewhere before and had remembered vaguely ever since. It was none other than Ceti eel Concept #1, deftly combining an armoured body that resembled a somewhat extreme example of an adult female trilobite beetle with those instantly-recognisable terminal cerci that had hitherto foiled every attempt by me to identify the Beast of Brunei.

Sketch of Ceti eel Concept #1 (© Ken Ralston/Robert S. Sallin/Paramount Pictures)

Sketch of Ceti eel Concept #1 (© Ken Ralston/Robert S. Sallin/Paramount Pictures)Although the thoracic scute spines on Ceti eel Concept #1 are much lengthier and more attenuated than those of the Beast, it can readily be seen from the above illustration that the former fictitious creature is much more similar to the latter mystery one than any other candidate that has been considered so far.

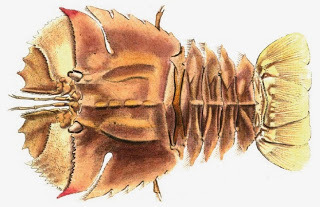

So where does this leave the Beast of Brunei? Of the various identities that have been proposed and noted here, the surviving anomalocarid contender seems least likely. For although it cannot be entirely ruled out that a lineage of these archaic invertebrates has persisted to the present day undiscovered by science, the fact that there is no trace whatsoever in the known fossil record of such an immensely extensive period of anomalocarid survival as 400 million years renders this possibility highly unlikely. (Having said that, however, we must be scrupulously fair and point out that the most recent anomalocarid species, Schinderhannes bartelsi, currently known from just a single specimen, is 100 million years younger than the next most recent species, so there is a confirmed 100-million-year gap in the anomalocarids' fossil presence; could there also, therefore, be a later, 400-million-year gap?)

A model of an anomalocarid, genus Anomalocaris, at Australia's National Dinosaur Museum in Canberra (Photnart/Wikipedia)

A model of an anomalocarid, genus Anomalocaris, at Australia's National Dinosaur Museum in Canberra (Photnart/Wikipedia)If the Beast of Brunei is an adult female or a juvenile trilobite beetle, then it is apparently a very distinctive, undescribed species, because its armour differs markedly from any species whose morphology I am aware of, and its cerci are unique. Of course, there is the faint possibility that these latter structures are not cerci at all, and even that they are not actually attached to the animal – perhaps they are merely something upon which the animal is resting, because they do appear somewhat misaligned. Alternatively, one FB friend suggested that they resembled the tail of a fish that had been attached somewhat inexpertly to the animal's posterior end. As for the animal's legs and possible antennae visible at its anterior end, these are not sufficiently clear in the photo to enable any detailed comments concerning them to be made.

Despite allegedly having been found in a river, the Beast of Brunei does not correspond physically to any known taxon of crustacean. Perhaps the nearest are the so-called Balmain bugs or butterfly fan lobsters Ibacus spp. of Australia, but these are marine crustaceans, not freshwater, and their morphological similarities to the Beast are only very minor anyway. In reality, this anomalous creature does not correspond to any known taxon of any invertebrate.

An illustration from 1815 of a Balmain bug

An illustration from 1815 of a Balmain bugWhat it does correspond most closely to, conversely, is an imaginary entity created for a science fiction film. So is the Beast an unofficial (albeit skilfully-manufactured) Ceti eel replica? If so, unless it had originally been created as a distinctive, mobile fishing lure, why was it found in a Brunei river? Or was it? Is this enigmatic creature's entire story (if anything with such scant details can even be referred to as a story anyway) no less fictitious than the Ceti eel? That is, could it be that the Beast wasn't found in a river at all, but was an artificial creation photographed (or even photoshopped) by persons unknown, and then utilised as the basis of yet another zoologically-themed internet hoax?

If it IS genuine, then its extraordinary, unparalleled combination of morphological attributes suggests that the Beast of Brunei is a truly remarkable zoological discovery of potentially profound scientific significance – and especially so if by extreme good fortune the animal itself has been preserved. But as almost a month has now passed since its internet debut yet without anything further emerging online regarding it, in my opinion the omens for its authenticity do not look good.

A very eyecatching female specimen of a Duliticola trilobite beetle species from Sabah, one of two Malaysian states present in northern Borneo (© Dave Dunford/Wikipedia)

A very eyecatching female specimen of a Duliticola trilobite beetle species from Sabah, one of two Malaysian states present in northern Borneo (© Dave Dunford/Wikipedia)Perhaps the situation concerning the Beast of Brunei and what it may (or may not) represent is best summed up on another website. On the Project Noah page containing Hazwan's photo of the Beast and the few details available concerning it, one reader suggested that Hazwan should send the photo and its details to a website called Whatsthatbug, which specialises in identifying unusual insects and other arthropods and generally achieves considerable success in this. Hazwan did so, and on 12 December they duly appeared on the following page - http://www.whatsthatbug.com/2013/12/12/unknown-thing-caught-fishing-brunei- under the heading 'Unknown "Thing" caught while fishing in Brunei'. And here is the response from this website's owners:

"We don't even know where to begin to classify this thing. We hope you are able to provide additional information. How large was this thing? Was it caught with a net or a fishing pole? Are there any additional photos showing the underside? Perhaps one of our readers can assist with this identification."

I accessed this page most recently during the early hours of today, 1 January 2014, when preparing the present ShukerNature article; at that time, no additional information had been supplied by Hazwan, and no assistance in identifying the creature had been offered by any reader.

I would love to be proved wrong, but somehow I don't think that we're going to be hearing any more about the Beast of Brunei – or, even if we do, I am not expecting it to shake the foundations of zoology any time soon.

Having said that: if anyone reading this ShukerNature post has any pertinent information concerning the Beast of Brunei and/or its possible identity, please do post details below – I'd be extremely interested to read them. Thanks very much!

Model of prehistory's famous 'Dudley bug' trilobite Calymene blumenbachii (© Dr Karl P.N. Shuker)

Model of prehistory's famous 'Dudley bug' trilobite Calymene blumenbachii (© Dr Karl P.N. Shuker)I am most grateful to Richard Muirhead for bringing this intriguing creature to my attention by posting on the Facebook Cryptozoology Group's wall the link to Hazwan's original Project Noah communication; and also to the following persons for their much-valued insights and opinions concerning its possible nature: Kevan Farmer, Kristian Lander, Cameron A. McCormick, Tim Morris, Jonathon Richter, Robert Schneck, Blake Smith, Spencer Thrower, Richard S. White, and Absentia Xuicoatl.

Close-up of the Beast of Brunei (© Hazwan)

Close-up of the Beast of Brunei (© Hazwan)

Published on January 01, 2014 06:44

December 30, 2013

THE LANAI HOOKBILL – A LESSON IN HOW SCIENTIFIC RECOGNITION CAN SOMETIMES COME TOO LATE

Schematic colour representation of the Lanaihookbill (L. Shyamal/Wikipedia)

Schematic colour representation of the Lanaihookbill (L. Shyamal/Wikipedia) There are a number of enigmatic species of bird that have fascinated me since childhood but regarding which I had only ever succeeded in uncovering the most scant of details prior to the coming of the internet, and for which I have now compensated by devoting entire ShukerNature blog posts to them. Click here , for example, to access my coverage of Madagascar's kinkimavo and the Bornean bristle-head; click here for the so-called Bourbon Island hoopoe, actually an extraordinary, now-extinct starling; and click here for the decidedly clamorous go-away-birds. Another one of these near-mystery birds is the Lanai hookbill, traditionally confined to the briefest of footnotes in Planet Earth's vast ornithological encyclopaedia. But no more. Here at last is a more detailed account worthy of this interesting, unusual, and engaging (but also very tragic) little bird.

The Hawaiian islands are home to a remarkable taxon of small, brightly-coloured finch-like birds (sometimes given separate family status) that are found nowhere else in the world. Known collectively as the drepanidids or Hawaiian honeycreepers, their 30-odd species sport such delightful native names as the iiwi, amakihi, anianiau, palila, ula-ai-hawane, and akiapolaau. They have attracted considerable ornithological interest on account of their wide diversity of beak shapes. Some species have short thin pointed beaks useful for catching insects, others have broad powerful beaks adept at splitting seeds and nuts, and still others have long curved slender beaks for dipping into flowers in search of nectar.

A selection of Hawaiian honeycreeper species, demonstrating their extreme diversity in beak form (© H. Douglas Pratt)

A selection of Hawaiian honeycreeper species, demonstrating their extreme diversity in beak form (© H. Douglas Pratt)Tragically, however, many of these attractive little birds are now either extinct or gravely endangered, due to a lethal combination of avian diseases brought to the islands by non-native birds introduced by man, habitat destruction, predation by other introduced non-native creatures such as rats, and slaughter for their pretty feathers to be used in tribal decorations.

The iiwi Vestiaria coccinea – one of the most beautiful and also (thankfully!) still one of the more abundant (relatively speaking) of the Hawaiian honeycreepers, although even its numbers have declined sufficiently in recent times for it to be categorised nowadays as Vulnerable by the IUCN (© Jack Jeffery/American Bird Conservancy – click

here

for more details of this organisation's sterling work)

The iiwi Vestiaria coccinea – one of the most beautiful and also (thankfully!) still one of the more abundant (relatively speaking) of the Hawaiian honeycreepers, although even its numbers have declined sufficiently in recent times for it to be categorised nowadays as Vulnerable by the IUCN (© Jack Jeffery/American Bird Conservancy – click

here

for more details of this organisation's sterling work)As a result, some honeycreepers are little-known, represented by only a few specimens and scant native information – but none more so than the Lanai hookbill. That is because this enigmatic species is known entirely from a single specimen and just two other sightings by the person who obtained that specimen.

On 22 February 1913, ornithologist George C. Munro spied an unfamiliar honeycreeper in the Kaiholena Valley on the small Hawaiian island of Lanai. The trusting little bird, predominantly yellow in colour but with darker wings, legs, nape, and top of head, plus a notably hooked parrot-like beak, chirped and flew to a spot near to him.

Sadly, however, as this was still a time when collecting specimens of birds for museums and private collections interested scientists far more than conserving them alive in their natural habitat, Munro promptly shot it, and after examining its corpse he realised that this bird did not correspond with any other honeycreeper species on record.

Acrylic on paper painting of the Lanaihookbill's type (and only) specimen (© Julian Hume)

Acrylic on paper painting of the Lanaihookbill's type (and only) specimen (© Julian Hume)When it was formally described in 1919 by Hawaiian bird specialist Robert C.L. Perkins, he declared that it represented a new species (and genus), which he duly named Dysmorodrepanis munroi after Munro. Moreover, Munro claimed to have had two further sightings of birds fitting his shot specimen’s description (one on 16 March 1916, the other on 12 August 1918, both of them in Lanai's southwestern portion).

Even so, no additional example has ever been obtained; nor have any other sightings been reported since 1918. As most of its forest habitat on Lanai had been cut down and replaced by pineapple fields by 1940, however, the hookbill's absence here is little short of inevitable, especially when coupled with the introduction onto its island home of rats and cats, as well as avian diseases brought here by non-native bird species.

Nevertheless, for a long time the Lanai hookbill was brusquely dismissed by the ornithological world as either a beak-deformed, semi-albinistic female specimen of a superficially similar species of Hawaiian honeycreeper known as the ou Psittirostra psittacea (now critically endangered), or a rare hybrid of two separate Hawaiian honeycreeper species.

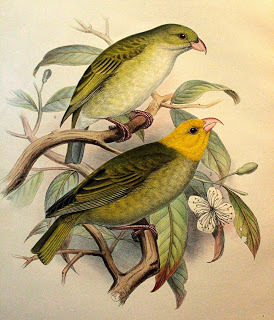

Female ou (above) and male ou (© F.W. Frohawk)

Female ou (above) and male ou (© F.W. Frohawk)In June 1989, conversely, a very detailed reassessment of its unique, type specimen (preserved at the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu) by ornithological researchers Drs Helen F, James, Richard L. Zusi, and Storrs L. Olson, published in the Wilson Ornithological Society's quarterly Wilson Bulletin, revealed that it was a genuine species after all. Certainly, its tongue and in particular its truly remarkable beak (whose mandibles yielded a noticeable gap even when closed, so that they resembled pincers, and may have been used for feeding upon snails) were very distinctive.

Tragically, however, with no sightings on record for many decades, the Lanai hookbill is unquestionably long-extinct - its belated scientific recognition having come far too late to save this fascinating little bird.

Beautiful illustration of the Lanaihookbill as featured in the Wilson Bulletin paper by James, Zusi, and Olson (© Nancy Payzant/Wilson Bulletin)

Beautiful illustration of the Lanaihookbill as featured in the Wilson Bulletin paper by James, Zusi, and Olson (© Nancy Payzant/Wilson Bulletin)This ShukerNature article is dedicated with love to my late grandmother, Gertrude Timmins, whose birthday it is today; she passed away in 1994 at the very venerable age of 99. Nan always said how her mother had told her that just moments after she was born, the bells welcoming in the New Year began pealing all over town. Nan was my Mom's mom, and I know that they are together in Heaven with God, looking down on me now as I deal with the last few hours of 2013, after which I shall at last be rid of this accursed year that took Mom from me. God bless you Mom and Nan, and I pray that 2014 will be a better year.

Published on December 30, 2013 17:39

December 26, 2013

YOU'LL BELIEVE AN ELEPHANT CAN FLY…POSSIBLY? PACHYDERMS WITH WINGS - AND OTHER STRANGE THINGS!

Roger Dean's spectacular flying elephant artwork for the cover of the second Osibisa album, Woyaya (© MCA/Osibisa/Roger Dean)

Roger Dean's spectacular flying elephant artwork for the cover of the second Osibisa album, Woyaya (© MCA/Osibisa/Roger Dean)Although I pride myself on covering the more unusual and unexpected of subjects in this blog, flying elephants is a first even for ShukerNature. Then again, it is the festive season – and if we can't suspend disbelief at this time of year (which is, after all, the one period when our faith in the reality of certain other gravity-unencumbered ungulates – namely, aerial reindeer - is all but compulsory), then when can we? So here, as a yuletide diversion, is my exclusive examination of airborne pachyderms.

And where better to begin than with the most famous example of all – Walt Disney's Dumbo.

Dumbo in triplicate – a selection of Disney plush toys (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Dumbo in triplicate – a selection of Disney plush toys (© Dr Karl Shuker)In contrast to the predominant policy during the first half-century or so of Disney-produced animated feature films, the movie Dumbo, released in 1941 and Walt Disney Productions' fourth such feature, was not based upon or even inspired by a well-known novel or traditional fairy tale. Instead, it emanated directly from a scarcely-known short story written by Helen Aberson and illustrated by Harold Pearl that had only just been released in a newly-devised prototype story-telling toy format known as Roll-A-Book in late 1939 when it was seen by Kay Kamen, Disney's head of merchandise licensing. When she showed it to Walt Disney, he was instantly convinced that its rights should be purchased and its story used as the basis of a future animated feature. This is indeed what happened, very swiftly too, and the rest is history.

Making friends with Dumbo (© Dr Karl Shuker)

Making friends with Dumbo (© Dr Karl Shuker)This all-time classic Disney film centres around a baby travelling-circus elephant christened Jumbo Junior by his mother, Mrs Jumbo, but whose extra-large ears make him the butt of spiteful jokes by the other circus elephants, who also cruelly nickname him Dumbo. And when his mother tries to protect him, she is taken away and imprisoned in solitary confinement as a mad elephant. Happily, however, Dumbo is briefly reunited with her in a touching scene that features her singing to him while still in jail the tear-jerking lullaby 'Baby Mine'. Following an accidental, champagne-induced bout of inebriation in which he hallucinates a psychedelic panorama of pink elephants, Dumbo and his only friend, Timothy Mouse, assisted by a raucous but good-hearted flock of crows, make the astonishing discovery that he can actually use his huge ears as wings and fly! As a result, Dumbo the flying elephant soon becomes the star of the entire circus, and his mother, swiftly released from jail, now proudly resides in her son's opulent private circus carriage.

The Dumbo merry-go-round at Walt Disney World (© Dr Karl Shuker)

The Dumbo merry-go-round at Walt Disney World (© Dr Karl Shuker)At only 64 minutes long, Dumbo is among the shortest of all animated features, but that didn't prevent it from becoming one of Disney's best-loved cartoon films. It also won the Academy Award for 'Best Scoring of a Musical Picture' in 1941 (and 'Baby Mine' was nominated that same year for the 'Best Original Song' Academy Award). Moreover, one of the most popular attractions, especially among small children, when visiting Disneyland (opened in Anaheim, California, in 1955), Walt Disney World (opened in Orlando, Florida, in 1971, and which I visited in 1981), and Disneyland Paris (opened in Paris, France, in 1992) is the Dumbo merry-go-round.

However, Dumbo is not the only cartoon flying elephant. Indeed, he is not even Disney's only cartoon flying elephant.

Down through the years, Disney has produced a succession of Winnie the Pooh featurettes. The second and most critically acclaimed of these was Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day, released in 1968, which deservedly won the 'Best Animated Short Film' Academy Award that year. This was no doubt due to it not only featuring the screen debut of the very popular and delightfully wacky character Tigger, but also for including a decidedly surreal but extremely memorable, song-accompanied dream/nightmare sequence. In this sequence, Pooh desperately strives to protect his beloved honey from a multi-coloured, polka-dotted plague of elephants and weasels - or, as Tigger amusingly mispronounces them, heffalumps and woozles. And among the former contingent of would-be honey pilferers is an enormous winged bumblebee with the head and the limbs of an elephant. An elebee, or a bumblephant?

Pooh and his honey pot attracts unwelcome attention from a flying heffalump of the bumblebee persuasion (© Walt Disney Productions)

Pooh and his honey pot attracts unwelcome attention from a flying heffalump of the bumblebee persuasion (© Walt Disney Productions)Moving to a very different but no less spectacular artistic representation of flying elephants: in 1970, the celebrated fantasy artist Roger Dean was commissioned to prepare two striking album covers for the Ghanaian Afro-pop band Osibisa, based in London. The result was a pair of extraordinarily eyecatching, totally unforgettable illustrations. The first of these, for the band's self-titled debut album, Osibisa, released by MCA in 1971, featured some flying elephants of normal grey colouration but sporting huge multicoloured wings and a decidedly sinister, malevolent demeanour. The second one, for the band's follow-up album, Woyaya, also released by MCA in 1971, featured a single scarlet-skinned flying elephant equipped with a long slender pair of translucent dragonfly-like wings, and claws instead of hooves.

Roger Dean's wonderful artwork for the first Osibisa album's cover (© MCA/Osibisa/Roger Dean)

Roger Dean's wonderful artwork for the first Osibisa album's cover (© MCA/Osibisa/Roger Dean)Although flying elephants have yet to feature in any cryptozoological case, one such example has indeed appeared in a truly delightful publication of the pseudozoological variety.

I coined the term 'pseudozoology' quite some time ago to describe spoof publications and specimens, i.e. books describing totally fictitious creatures but in such a completely sober, straight-faced manner that they deliberately give the impression that the animals documented by them are real, and specimens created artificially but afterwards presented or publicly exhibited as if they were genuine. Originally published in German in 1957 and first published in English a decade later, perhaps the most famous, celebrated work of pseudozoology is The Snouters: Form and Life of the Rhinogrades. Those were respectively the colloquial and the formal zoological names given by the book's equally fictitious German author, Prof. Harald Stümpke, to a unique taxonomic group of mammals that had lately been discovered in a now-sunken Pacific archipelago. As chronicled by him in detail, they all exhibited extreme nasal modifications, enabling certain species to walk upon their noses, and some even to catch prey with them.

The Snouters: Form and Life of the Rhinogrades

(© University of ChicagoPress)

The Snouters: Form and Life of the Rhinogrades

(© University of ChicagoPress)Less familiar but no less entertaining is Dr. Ameisenhaufen's Fauna, researched by Joan Fontcuberta and Pere Formiguera, and published in 1988. In this book, they too describe a range of fantastic creatures all of which were claimed to be real by the brilliant but mysteriously missing Munich-born zoologist Prof. Peter Ameisenhaufen (in a delightful, knowing in-joke for pseudozoological aficionados, Ameisenhaufen is also credited in this book as being closely associated with rhinograde researcher Harald Stümpke). These creatures include such wonders as the olpico-nu Cercopithecus icarocornu, a winged unicorn monkey from Brazil's Amazon jungle; Solenoglypha polipodida, a 12-legged lizard-like reptile with venomous bite and hypnotic whistle, as well as a selection of avian attributes, hailing from Tamil Nadu in southern India; and the hengo-go Threschelonia atis, a tortoise-carapaced ibis from the Galapagos archipelago. Most astonishing of all, however, is a winged elephant from Kenya known as the aerophant, but even the exceedingly open-minded Ameisenhaufen had difficulty in accepting its reality, which is based principally upon the following dubious photograph:

A pair of aerophants (© European Photography)

A pair of aerophants (© European Photography)Wonderful!

An expertly photomanipulated aerophant-like flying elephant against an unexpected backdrop (© Ozile/Deviantart.com – for full details, click here)

An expertly photomanipulated aerophant-like flying elephant against an unexpected backdrop (© Ozile/Deviantart.com – for full details, click here)Flying elephants may not be known in mainstream zoology, or even in cryptozoology, but they certainly appear in traditional Eastern legends and lore. For example, according to one such fable, all elephants were originally winged. One day, however, an elephant alighted upon a banyan tree somewhere north of the Himalayas and crashed down upon a meditating holy man sitting beneath its branches, because the elephant was too heavy for the tree to support its great weight. The holy man – a yogi named Dirghatapas - was so angered by this that he cursed the poor elephant, causing its wings to fall off. And since that fateful day, all elephants have been wingless.

A golden statuette of a flying elephant, symbolising Koetai Kartanegara Sultanate (© Agus EM)

A golden statuette of a flying elephant, symbolising Koetai Kartanegara Sultanate (© Agus EM)In Chinese mythology, a white rat called Hua-hu Tiao was kept by Mo-li Shou, one of the four Diamond Kings of Heaven, inside a bag made from panther skin. But when Mo-li Shou decided to teach mortal humans the error of their ways, he released Hua-hu Tiao, who immediately transformed into a white-winged flying elephant and began devouring them – until it swallowed the hero Yang Chien, who promptly killed this monstrous beast by tearing its heart in two and ripping open its belly from the inside.

Fantasy white flying elephant artwork (© Yuliya/Golden Section Jewellery – click herefor more details)

Fantasy white flying elephant artwork (© Yuliya/Golden Section Jewellery – click herefor more details)There is also a Bhili folktale that tells of how a flying elephant came down from the sky each night to eat a farmer's sugar cane in his fields, until one night the farmer lay in wait, and when the elephant landed, he seized hold of its tail. The elephant flew off, carrying the farmer with it, to the supreme Hindu deity Indra's kingdom of Paradise. There the farmer met Indra, who apologised for the elephant's theft and permitted the farmer to take whatever he wished in recompense. The farmer was content to take two handful of gems, and he was then carried back down to Earth by the elephant. Now a rich man, the farmer built a big house for himself and his family, but it wasn't long before all of his neighbours learnt how he had obtained the gems.

Eastern flying elephant painting (© Irena Shklover)

Eastern flying elephant painting (© Irena Shklover)Eager to emulate his good fortune, they swiftly planted their own field of sugar cane, in order to lure Indra's heavenly elephant down to Earth, having decided that they too would be transported to Paradise but would then take back home with them much more treasure than just two handfuls of gems. When the elephant flew down, they seized hold of each other in a chain, with the neighbour at one end of the chain holding the elephant's tail, and in this way they were indeed carried up towards Paradise when the animal flew away. Unfortunately for them, however, before they reached their destination the neighbour holding the elephant's tail stretched open his arms while describing how much wealth he planned to bring back home, and in so doing he let go of the tail, thus causing all of the villagers including himself to fall back down to Earth. When Indra learned of the villagers' greed, he planted a field of sugar cane himself, in Paradise, so that now his flying elephant would never come down to Earth again, and the villagers would therefore never be able to reach Paradise in search of its treasure.

Celestial flying elephant (original image source unknown to me)

Celestial flying elephant (original image source unknown to me)Flying elephants are also represented diversely in Asian art. For instance: a flying elephant is the symbol of Koetai (aka Kutai) Kartanegara Sultanate, a regency in Indonesia's East Kalimantan province on the island of Borneo.

The magnificent statue of a winged elephant at Chiang Mai (© Jen K/Flickr)

The magnificent statue of a winged elephant at Chiang Mai (© Jen K/Flickr)An enormous, venerated statue of a resplendant winged elephant stands majestically in Chiang Mai in Thailand, where it is a very popular tourist attraction. And back in Indonesia, especially Bali, beautifully painted winged elephants carved by local craftsmen from albesia wood are frequently hung as mobiles in homes and temples there, where they allegedly chase away evil spirits.

My Balinese winged elephant mobile (© Dr Karl Shuker)

My Balinese winged elephant mobile (© Dr Karl Shuker)As for the West: children's author Enid Blyton got in on the act by writing a Noddy book entitled Noddy and the Flying Elephant, first published in 1952 by Sampson Low. This was also the first book in the 'Noddy Ark' series.

Noddy and the Flying Elephant

(© Enid Blyton Estate/Sampson Low)

Noddy and the Flying Elephant

(© Enid Blyton Estate/Sampson Low)In short: aerial reindeer may be of seasonal occurrence only, and we all know how likely it is that pigs will fly. As far as flying elephants are concerned, conversely, they are clearly a lot more abundant around the world than you may have previously realised. But please ensure that you don't sit beneath the branches of a tree in which one has just alighted, because if you do, the fate of Dirghatapas may not be the only unpleasant experience in store for you. Remember, elephants eat plenty of fibre...

And finally: if you're wondering why - or how - I've resisted mentioning anything about jumbo jets, it's only because I've been biding my time. For here, ladies and gentlemen, I give you right now, in the following video (kindly brought to my attention by Fortean researcher Bob Skinner), the jumbo jet to end all jumbo jets! Click here , and all will be revealed!

Well, we can't be serious all the time!

A very charming flying elephant created by Photoshop (© worth1000.com)

A very charming flying elephant created by Photoshop (© worth1000.com)

Published on December 26, 2013 13:55

December 15, 2013

THE DRAGONS OF OCEANIA

Bunyip (© Richard Svensson)

Bunyip (© Richard Svensson)Dragons belonging to the wingless but quadrupedal classical category are most closely associated with Europe, but some have been reported far away from that continent. Among the most fascinating yet least-known of these remotely-located classical dragons were those of Oceania.

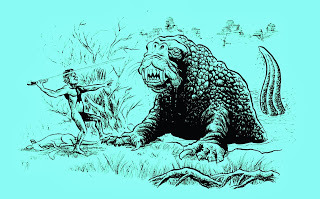

Australia was home to several very different forms. One of them was a freshwater version known as the kurreah, which inhabited Boobera Lagoon's deep lakes and underground springs in New South Wales. Thanks to its crocodilian jaws, it was sometimes assumed by Westerners to be nothing more than a real crocodile, but was much more than that. Not only was its body very elongate and snake-like, its extremely lengthy, slender tail was prehensile, able to grip anything that it wrapped its tip around. Its feet were broadly webbed, it sometimes sported exotic frills around its neck, was of colossal size, covered in thick scales, and occurred in several different colours, including green and orange. If a kurreah spied anyone swimming in its abode, it would not hesitate to seize the hapless human in its huge jaws and haul him underwater, to drown and then devour him.

Kurreahs (© Janet & Anne Grahame Johnstone/Purnell & Sons Ltd)

Kurreahs (© Janet & Anne Grahame Johnstone/Purnell & Sons Ltd)Even more ferocious than the kurreah, however, was the burrunjor, a huge wingless dragon named after a remote expanse of Arnhem Land in northern Australia called Burrunjor where it allegedly roamed – and still does today, at least according to local aboriginal testimony. Whereas most classical dragons were quadrupeds, the burrunjor was bipedal, striding purposefully along upon its hind limbs like a carnivorous theropod dinosaur from prehistory, and aboriginal cave art portraying a creature fitting this description still exists in the Burrunjor region. Similar monsters also exist in the folklore of several tribes inhabiting Papua New Guinea.

Burrunjor (© William Rebsamen)

Burrunjor (© William Rebsamen) Another bipedal dragon Down Under was the gauarge or gowargay. Resembling a featherless emu, this pitiless monster frequented water holes. If anyone were foolish enough to bathe in a gauarge's water hole, it would whip it up into a mighty whirlpool and drag the unfortunate bather down into its swirling depths to drown him.

A notably dragonesque bunyip (© Angus McBride)

A notably dragonesque bunyip (© Angus McBride)The most famous freshwater dragon in Australia, however, was definitely the bunyip. Although modern reports of mysterious creatures reputed to be bunyips are often likened to dog-headed mammalian creatures, the traditional bunyip of aboriginal lore was a huge aquatic wingless dragon, whose fearsome presence was readily made apparent by its spine-chilling, ear-splitting bellow.

Bunyips were fiercely protective of their young, and one famous myth tells of how a whole tribe was transformed into black swans when one of their hunters abducted a young bunyip from its lake and was relentlessly pursued by its enraged mother, in whose wake the entire lake was drawn up, completely submerging the tribe's village.

The story of the bunyip and the villagers transformed into black swans, in Once Long Ago (1962), retold by Roger Lancelyn Green and illustrated by Vojtěch Kubašta (© Roger Lancelyn Green/ Vojtěch Kubašta/Golden Pleasure Books) [to read these pages, click their images to enlarge them]

The story of the bunyip and the villagers transformed into black swans, in Once Long Ago (1962), retold by Roger Lancelyn Green and illustrated by Vojtěch Kubašta (© Roger Lancelyn Green/ Vojtěch Kubašta/Golden Pleasure Books) [to read these pages, click their images to enlarge them]The mindi was a very specialised form of bunyip, very serpentine in body form, so was sometimes referred to as a bunyip-snake and deemed to be a rainbow dragon too. Of immense size, and possessing magical powers according to the ancient lore of the Yarra Yarra aboriginal people, it could readily poison any would-be attacker and also spread disease.

Yet another water dragon of Australia was the oorundoo, native to the Murray River. According to aboriginal legends, this enormous aquatic beast created Lakes Victoria and Albert.

New Zealand's native dragons were (or are?) the taniwha. Looking somewhat like gigantic gecko lizards or colossal tuataras (the tuatara being a unique, primitive reptile surviving only in New Zealand), but bearing a row of long sharp spines along the centre of their back, taniwha are still seriously believed in even today by the Maori people, and are said to have formidable supernatural powers.

Taniwha carving (public domain)

Taniwha carving (public domain)In 2002, a major highway in New Zealand had to be rerouted because of Maori claims that it would otherwise intrude upon the abode of a taniwha. And as recently as 2012, a similar objection arose in relation to the planned $2.6 billion construction of a tunnel in Auckland, with protestors claiming that this would disturb a taniwha that lived under the city.

Auckland notwithstanding, these formidable dragons normally inhabited dark, secluded localities on land, as well as in large freshwater pools, and sometimes in the sea too, and were reputedly able to tunnel directly through the earth, often causing floods or landslides as a result. Each taniwha was allied to a specific Maori tribe that it protected as long as it received a fitting level of respect and veneration, but it would often attack and devour members of other tribes.

Also present in Maori traditions are the ngarara – giant lizard-like land dragons seemingly resembling monitor lizards (even though these are not known to be native to New Zealand). Various ngarara could assume the form of a beautiful young woman (as could some taniwha).

An ngarara depicted upon a New Zealand postage stamp issued in 2000 (© New Zealand Post Office/New Zealand Government)

An ngarara depicted upon a New Zealand postage stamp issued in 2000 (© New Zealand Post Office/New Zealand Government)Very prevalent in traditional Hawaiian mythology is an enormous shiny-black wingless dragon of infamously mercurial temperament known as the moho or mo'o. Like certain dragons of New Zealand but otherwise unlike most dragons elsewhere in the world outside the Orient, the moho was a skilled shape-shifter, normally measuring 10-30 ft long but able to transform instantly if need be into a tiny, inconspicuous gecko-like lizard, as well as a beautiful seductive woman.

Invariably associated with water, the moho was predominantly a guardian spirit deity, protecting individuals or entire families, as well as districts, and specific localities such as fishponds – which if deep enough were frequently inhabited by these dragon deities. Although they would often remain hidden beneath the water, consuming in ecstasy the intoxicating kava root, their presence in such ponds was betrayed if there was foam upon the surface, or if fishes caught there tasted bitter.

Mo'o carved from stone, by Hoaka Delos Reyes (© Honolulu Advertiser)

Mo'o carved from stone, by Hoaka Delos Reyes (© Honolulu Advertiser)Similar dragons were reported from other Pacific Ocean islands or island groups too, including Tahiti and Tonga. Indeed, they were actively worshipped on Tahiti by the royal Oropa'a family. And on Tonga, lizard-like or crocodile-like dragons of prodigious size and lake-dwelling propensity, reputedly sent by the gods, would seize unwary bathers or women washing items in their lakes, and promptly plunge down into the water with them, drowning their unfortunate victims beneath the surface.

My favourite bunyip-featuring newspaper cartoon (© Daily Mirror, Sydney, 9 June 1978)

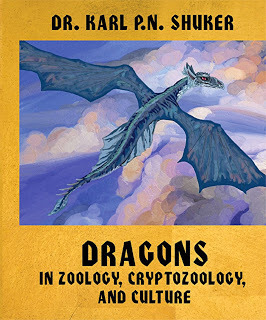

My favourite bunyip-featuring newspaper cartoon (© Daily Mirror, Sydney, 9 June 1978)This ShukerNature blog is an exclusive excerpt from my latest, newly-published book, Dragons in Zoology, Cryptozoology, and Culture (Coachwhip Publications: Greenville, 2013).

Published on December 15, 2013 12:43

December 11, 2013

PIGGING OUT AT CHRISTMAS - IT'S GRIM WITH THE GLOSO

Chased by the gloso! (© Richard Svensson)

Chased by the gloso! (© Richard Svensson)Welcome to a seasonal ShukerNature post, featuring a little-known but greatly-feared preternatural creature long associated with Swedish Yuletide.

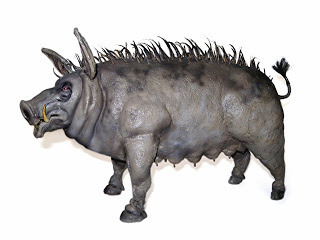

In Britain, the animals most closely linked to Christmastime via folklore and other traditions include such familiar and generally friendly species as the robin, the reindeer, and the turkey. In Skåne and Blekinge, the two southernmost provinces of Sweden, conversely, a very different, and far more daunting, creature pervades the Season of Goodwill, and its presence is anything but good. Scarcely known outside its Scandinavian provenance, outwardly it resembles a pig, but no ordinary one, for this preternatural entity is in many ways the porcine equivalent of Britain's phantasmal Black Dogs, and is just as dangerous!

Most commonly referred to as the gloso (other names for it include the galoppso and the gluppso, all translating as 'galloping sow'), this dire beast is grim in every sense of the word. This is because the gloso is a church grim (or kyrkogrim in Sweden), i.e. a supernatural creature derived from the spirit of an animal or person supposedly sacrificed when the foundation of a church was built, and which now protects the church and its grounds for all eternity, and cannot be killed by any normal weapon. Generally, the gloso lives either within the cemetery of the church to which it is bound, or within a mound in a field directly adjacent to that church.

A stop-motion puppet of the gloso from a film by Richard Svensson (© Richard Svensson)

A stop-motion puppet of the gloso from a film by Richard Svensson (© Richard Svensson)Those unfortunate enough to have encountered this terrifying entity liken it in basic appearance to an enormous female domestic pig, usually jet-black in colour (though sometimes ghostly white), but with a ridge of razor-sharp spines or bristles running down the centre of its back, a pair of huge tusks curving out from its jaws, eyes that glow a fiery red, and the fearful yet very real ability to breathe fire. Other tangible, physical abilities attributed to the gloso, and which thereby distinguish it from insubstantial ghosts or spectres, include its predilection for devouring fresh corpses in the churchyard and for sharpening its tusks upon gravestones. It also leaves visible tracks in its wake.

The gloso can be encountered at any time during the year, but it is said to be at its most malign during the week linking Christmas and the New Year. And yet it is during this same week when it can also be its most beneficial – provided a certain magical rite associated with it is performed correctly. If this rite is not, however, the person performing it will not live to see in the New Year!

According to Swedish legend, on the evening of Christmas Day (and also on New Year's Eve) anyone can discover everything that will happen to them during the incoming New Year if they are brave enough to withstand an assault by the gloso. The ritual stipulates that after the sun has set, you must visit four different churches in four different parishes, walk around each church in an anti-clockwise direction, and then blow through the keyhole of each church's door. After blowing through the keyhole of the fourth church's door, if you then peer through it you will witness all of the most notable events that await you in the New Year, rushing before your eyes in a rapid stream of images like a speeded-up movie film.

Another view of the stop-motion gloso puppet from a film by Richard Svensson (© Richard Svensson)

Another view of the stop-motion gloso puppet from a film by Richard Svensson (© Richard Svensson)But for such precious insights, you must pay a steep price – the wrath of the gloso. For it will abruptly appear and chase after you, spurting hot blasts of fire at your rear end and striving to run between your legs so that its ridge of razor-sharp bristles can rip you apart. Happily, however, if you are brave enough to attempt the feat, there is one way in which this dread beast can be pacified – by turning around and facing it, with an arm outstretched, offering it a loaf of bread. If the gloso allows you to feed it the bread, you are safe. If not...

In some variations upon this legend, the same gift of New Year foresight can be obtained by confronting the gloso at a crossroads instead. As a teenager, the maternal grandmother of Swedish artist and cryptozoologist Richard Svensson once visited a crossroads in Blekinge on New Year's Eve for the express purpose of conjuring forth the gloso – though merely to see it rather than to witness what the New Year held in store for her. (Un)fortunately, however, the gloso failed to materialise.

The gloso, from a bestiary by Richard Svensson (© Richard Svensson)

The gloso, from a bestiary by Richard Svensson (© Richard Svensson)The gloso is also part of a much lengthier, more complex magical ritual in which the person taking part is hoping to gain psychic talents, and this multi-stage ritual has to be performed on several different magically-potent dates, including Christmas night once again. Here is how Swedish folklorist Håkan Lindh described it to me: