Andy Zaltzman's Blog, page 9

November 21, 2011

A Pythonesque Test

Sure, he can take a six-for on debut at the age of 18, but can he convince his parents to hand over the car keys for the weekend?

© AFP

As the Johannesburg Test slalomed in a spectacular way towards its baggy-green denouement, the TV cameras pick out a placard in the crowd which posed the question: Is Test cricket dead? Perhaps on the reverse side, there was a range of multiple-choice answers, ranging from: (a) yes, it died the moment Australia won at The Oval in 1882; through (d) no, but it has been taken hostage by some angry-looking goons wearing IPL replica shirts and they do not seem especially keen on negotiating a civilised resolution to the stand-off; to (g) who cares, Mozart is dead too and his tunes are still damned catchy.

The cameras then resumed their more important regular task of zooming in annoyingly close as the ball is bowled to ensure that the viewer cannot fully see what happened until replays are shown, several of which have also been zoomed in to the point of perspective-obliterating meaninglessness, all the while prompting the watching cricket fan to ponder from the comfort of his or her sofa: Why is that, as televisions become bigger and bigger and better and better, TV cricket seems intent on showing a smaller and smaller part of the action?

I digress. Anyway, the evidence of the contest being played out in front of the placard suggests that the correct response was: "Is Test cricket dead? Is the Pope an aubergine?"

This was close to the perfect Test match, a game of constantly shifting momentum which contained more twists and turns than an ice-skating snake's high-risk Olympic final routine.

Innings of 30 or 40 were valuable, partnerships of 50 felt match-changing, every session saw the balance of the game wobbling from one side to the other like a drunken tightrope walker on a windy day.

On the evidence of the game, if not the crowd at the ground, Test cricket clearly is not dead. It might be in a nursing home, but, frequently, its faculties seem as sharp as ever. Admittedly, it does wish more people would come to visit it. And it is not entirely sure that it can trust all of its family members, some of whom seem to be scrabbling over its inheritance before it has even made its will.

Nevertheless, it was a little sad to see the final day this all-time classic match played to a stadium so sparsely populated that you wanted to give it a cuddle and tell it to keep its chin up. What can cricket do to attract fans to Test matches, without using military threats, or paying people twice their daily wage to attend?

Published on November 21, 2011 22:08

November 14, 2011

Multistat: 26

A West Indian fan tries to please a god to bless his side with powers against spin

© Trinidad & Tobago

26

The West Indies' collective Test batting average against spin since Brian Lara's retirement from international cricket in April 2007 – comfortably the worst such figure by any team other than Bangladesh.

In that time, West Indies have averaged 30.5 against pace bowlers – still not world-beating, as their results would vociferously and conclusively testify, but nevertheless 17% better than their average against spin. Since April 2007, all the other Test teams combined have averaged 34.5 against pace, and 39.5 against spin – the rest of the non-Caribbean planet has been 14% better against spin than pace.

Thus, since Lara dragged his magic bat away from the Test match arena for the last time, West Indies have been 11% worse than their peers against pace, but a staggering 34% worse against spin. All in a period when spinners have been collectively less effective in Tests than at any time since the 1940s. Their dedication to not playing spin very well has taken them to statistical troughs that no major Test nation has explored for generations.

No wonder R Ashwin must have punched the air with excitement after being told he would make his debut against them. And you can sympathise with Devendra Bishoo when he wears his "Why am I never allowed to bowl at my own team?" frown.

The decline of Caribbean batsmanship against slow bowling is highlighted by the fact that from 2000 until Lara's final Test West Indies averaged 27.8 against pace and 34.4 against spin – a 24% margin in favour of playing spin (similar to their performance through the 1980s and 1990s). In electoral terms, there has been a government-toppling swing towards the West Indians playing spin badly.

The major movers in the pace v spin batting market have been England, who had steadily averaged in the mid-to-low 30s against tweakers and twirlers since the 1960s, but who, since April 2007, have led the universe, averaging 47. Their improvement has been built upon hard work, sound planning, and the extremely wise tactic of not facing Warne, Muralitharan and Kumble anymore, and instead taking on Doherty, Mendis and Mishra. Of all the things the ECB have got right in helping the national team to the top of the Test Match tree, this has been one of their most influential moves.

Also: The number of Test centuries scored by Ricky Ponting in 62 Tests between August 2001, when he broke a 20-month century drought, and December 2006, when his 142 after being dropped early on by Ashley Giles sparked Australia's spectacular/gut-rendingly-harrowing (delete according to allegiance) Adelaide comeback victory over England. In that purplest of five-year patches, the Baggy-Green icon averaged 73.

In his 45 Tests over five-and-a-half-years before this halcyon period, Ponting had scored sevenb hundreds in 45 Tests, and averaged 40. In 48 Tests in just under five years since then, he has scored six hundreds and averaged 39 (including just one century in his last 23 Tests, none in his last 13, and no half-centuries in his last six) (and that one century would have ended exactly 100 runs before it reached 100, but for Mohammad Amir grassing a chance that most schoolboys would have taken) (given that Amir was the same age as a schoolboy at the time, that is a pertinent consideration).

Ponting's career has taken on an almost perfect symmetry – and one inverse to Brian Lara's. Lara averaged 60 in his first 33 Tests over five years, 60 in his final 54 Tests over five years, and over the five years in the middle, he averaged 39 in 47 Tests. Both men have overall career averages of 52, which goes to show that even the greatest players have it in them to impersonate Taufeeq Umar for half a decade.

Also: Faoud Bacchus' Test batting average. Does this constitute a disappointing average for someone with a highest Test score of 250, or does 250 constitute an amazingly brilliant highest score for someone with a Test average of 26? I will leave that to the philosophers and/or lawyers.

The 250 was Bacchus' only Test century, meaning that he scored more in his single three-figure innings than Tendulkar, Greg Chappell, Boycott, Gavaskar, Border, Kallis and Steve Waugh have done in their 230 collective hundreds, and more than any Englishman scored in 4444 innings between the Lord's Test of 1990, when Gooch plundered his way to 333, and the Edgbaston Test of last summer, when Cook plinked his way 293.

Published on November 14, 2011 21:39

November 10, 2011

A quiz on the capers in Cape Town

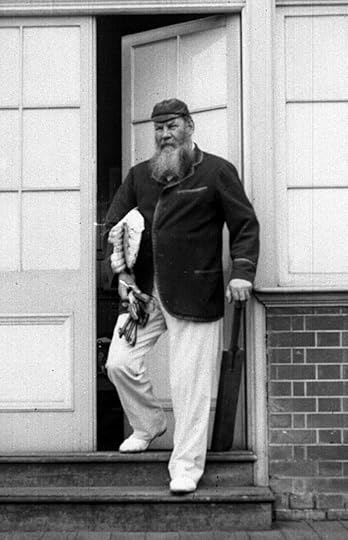

"Curse these fools, they want to take away every record I possess"

© Getty Images

In the 2015 previous Test matches that have adorned the history of the universe, few, if any, passages of play can have matched the barking-mad cricketing melodrama that unfolded in the 2016th in Cape Town on Wednesday. On a lively but scarcely fire-breathing wicket, mayhem reigned as the moving ball and the DRS ran amok like a porcelain-loving bull in a well-stocked china shop.

Australia, from a position of total dominance, lost, in quick succession: a few early wickets; their marbles; and control of the game. Haddin, in particular, seemed to be spooked by the scoreboard (which read an admittedly alarming 18 for 5), and forget the match situation, which was, effectively, 206 for 5. Philander and Morkel took full advantage, and the game was not so much turned on its head as flipped into an impromptu quadruple somersault, before staggering groggily to its feet, muttering: "Who am I and what am I doing here?"

Australia had history and an immortal entry in the annals of sporting ineptitude within their grasp – at 21 for 9 after 11.4 overs, they were within one more inept waft of registering the lowest-ever completed Test innings (New Zealand's 26 against England in 1954-55), and the shortest-ever completed Test innings (South Africa's 12.3 overs at Edgbaston in 1924). Siddle and Lyon stapled a small fig leaf of dignity to Australia's obvious embarrassment with a last-wicket stand of 26, and History mopped its brow and toddled off. But it did not leave empty-handed. Here then, is a multiple-choice quiz about the unforgettable day two of the Newlands Test. Each question has multiple answers. Do not attempt if you are (a) an Australian batsman, or (b) an Australian of nervous disposition.

1. What did Nathan Lyon do on Thursday that no other human being has ever done?

(a) He walked out to bat in a Test match with his team at 21 for 9. The previous worst score facing a No. 11 was 25 for 9, when Lyon's baggy green predecessor Tom McKibbin marched to the wicket at The Oval in 1896 thinking, "Oh dear. This is a disappointing score. I bet no other Australian will ever come to the wicket with a worse score than this on the board." He smote a defiant 16 before being caught, taking Australia's score up to 44 all out, leaving Hugh Trumble chuntering into his moustache at the non-striker's end that he had taken 12 for 89 in the match and still been on the wrong end of a shoeing.

(b) He broke the 300-mph barrier on a unicycle. Unicycling has been introduced to the Australian training regime by their new coaches, as a means of improving balance and self-confidence. Lyon took a morning pedal up to the top of Table Mountain, lost his balance whilst looking for a yeti, and careered down to Newlands at breakneck speed.

(c) He became the eighth No. 11 to top-score in a Test innings.

(d) He walked on the moon.

ANSWERS: (a) and (c). (b) has not been ratified by the World Unicycling Federation, as it took place outside of official competition.

Published on November 10, 2011 22:21

November 7, 2011

Multistat: 53.5

What will Sanga's Big Four-O unleash onto the world?

© AFP

Greetings, Confectionery Stallers. We have decided to incorporate the Multistats into the main blog. So there will be more blogs, but some of them will be shorter, and jam-packed with stats. If you are allergic to stats, or fearful of truth, you are cordially advised to ignore the Multistats blogs, or read them under medical and/or psychological supervision.

The Test average of Sri Lankan top-seven batsmen in their 30s since Kumar Sangakkara entered his fourth decade on this planet on October 27, 2007 – the best by any Test side in that time.

Over the same period, Sri Lankan top-seven batsmen under the age of 30 have averaged 31.6 – sixth best, ahead only of Pakistan and West Indies, and marginally so. (I have excluded Bangladesh, who have had hardly any over-30 players, Zimbabwe, who have played hardly any Tests, and Italy, who have (a) played no Tests at all and (b) been governed by Silvio Berlusconi, a man so naughty that he disqualifies his entire nation from the holy realm of cricket statistics. There. Someone had to say it.)

During this time (Sangakkara's 30s, not Berlusconi's rule over Italy), India's and Pakistan's top sevens have also registered a significantly higher average by gnarled 30-plus veterans compared with fresh-faced 20-somethings. India's heavily illustrious 30-plus batting brigade has averaged 50.3, and Pakistan's 45.5 (second and third best of the Test nations). Their under-30 averages are 37.3 and 31.4 respectively (fourth and seventh best).

West Indies are the only other team whose 30-plus oldies have outperformed their sub-30 youngsters in the last four years (41.7 to 30.7). Australia as a nation, slowly recuperating from the departure of its own generation of greats, pays little heed to baggy-green age (over-30s averaging 42.4, under-30s 44.5), whilst South Africa (43.6 to 52.3), England (39.5 to 47.2) and New Zealand (26.7 to 33.6) all show significantly better returns from their younger players.

Admittedly, Sangakkara's 30th birthday, joyous occasion though it no doubt was for him and his family, might not be the most scientifically unignorable milestone on which to base a stat. However, the fact remains that, since the Matale Machine blew out those 30 candles on his cricket-bat-shaped cake, not only has the world economy collapsed like St Brian's Primary School Under-9s in their little-reported match against West Indies in 1984, but it appears than an Asian-cricket lover may have secretly discovered the elixir of eternal youth ‒ since then, Asian batsmen have been 50% more effective when over 30 years of age than when under 30.

The figures suggest that the golden era of Asian batsmanship has left something of a void beneath, and one that will need filling as a matter of increasing urgency.

(By the way, in case you are reciting this stat during an attempted seduction, and the primary stat does not win the heart of your intended, here is a back-up stat to clinch the deal: in ODIs, these figures are mirrored very closely – over-30s versus under-30s ‒ other than by England's under-30 batsmen, who have been excellent in Tests, but have explored all conceivable crannies of underperformance in ODIs).

Also: The number of times, per hour, that the average Sri Lankan cricket fan wishes Murali was still fit and firing. Since he retired, Sri Lanka have not only failed to win any of their 14 Tests, but their bowlers have collectively averaged 45.

Over the course of his career, Murali twirled his country to 54 wins in 132 Tests, taking 795 Test wickets (excluding the Super Test where he played for the World XI) at 22; Sri Lanka's other bowlers in those games averaged 36. Even in the 23 Tests Murali missed during his career, his colleagues managed to average 37.

Not only was Murali a more than useful bowler himself ("probably better than Eddie Hemmings" – International Understatement Magazine, January 2008), but since his retirement, Sri Lankan bowling appears to have gone into a prolonged grump at the realisation that he has gone forever, subject to some major age-reversing advances in one or both of science and witchcraft.

In the words of Piglet's agent during a particularly heated argument over how to split the royalties from the latest Winnie The Pooh film, it has all been too much to bear. Boom.

Published on November 07, 2011 22:08

The oldies with the goldies

What will Sanga's Big Four-O unleash onto the world?

© AFP

Greetings, Confectionery Stallers. We have decided to incorporate the Multistats into the main blog. So there will be more blogs, but some of them will be shorter, and jam-packed with stats. If you are allergic to stats, or fearful of truth, you are cordially advised to ignore the Multistats blogs, or read them under medical and/or psychological supervision.

53.5

The Test average of Sri Lankan top-seven batsmen in their 30s since Kumar Sangakkara entered his fourth decade on this planet on October 27, 2007 – the best by any Test side in that time.

Over the same period, Sri Lankan top-seven batsmen under the age of 30 have averaged 31.6 – sixth best, ahead only of Pakistan and West Indies, and marginally so. (I have excluded Bangladesh, who have had hardly any over-30 players, Zimbabwe, who have played hardly any Tests, and Italy, who have (a) played no Tests at all and (b) been governed by Silvio Berlusconi, a man so naughty that he disqualifies his entire nation from the holy realm of cricket statistics. There. Someone had to say it.)

During this time (Sangakkara's 30s, not Berlusconi's rule over Italy), India's and Pakistan's top sevens have also registered a significantly higher average by gnarled 30-plus veterans compared with fresh-faced 20-somethings. India's heavily illustrious 30-plus batting brigade has averaged 50.3, and Pakistan's 45.5 (second and third best of the Test nations). Their under-30 averages are 37.3 and 31.4 respectively (fourth and seventh best).

West Indies are the only other team whose 30-plus oldies have outperformed their sub-30 youngsters in the last four years (41.7 to 30.7). Australia as a nation, slowly recuperating from the departure of its own generation of greats, pays little heed to baggy-green age (over-30s averaging 42.4, under-30s 44.5), whilst South Africa (43.6 to 52.3), England (39.5 to 47.2) and New Zealand (26.7 to 33.6) all show significantly better returns from their younger players.

Admittedly, Sangakkara's 30th birthday, joyous occasion though it no doubt was for him and his family, might not be the most scientifically unignorable milestone on which to base a stat. However, the fact remains that, since the Matale Machine blew out those 30 candles on his cricket-bat-shaped cake, not only has the world economy collapsed like St Brian's Primary School Under-9s in their little-reported match against West Indies in 1984, but it appears than an Asian-cricket lover may have secretly discovered the elixir of eternal youth ‒ since then, Asian batsmen have been 50% more effective when over 30 years of age than when under 30.

The figures suggest that the golden era of Asian batsmanship has left something of a void beneath, and one that will need filling as a matter of increasing urgency.

(By the way, in case you are reciting this stat during an attempted seduction, and the primary stat does not win the heart of your intended, here is a back-up stat to clinch the deal: in ODIs, these figures are mirrored very closely – over-30s versus under-30s ‒ other than by England's under-30 batsmen, who have been excellent in Tests, but have explored all conceivable crannies of underperformance in ODIs).

Also: The number of times, per hour, that the average Sri Lankan cricket fan wishes Murali was still fit and firing. Since he retired, Sri Lanka have not only failed to win any of their 14 Tests, but their bowlers have collectively averaged 45.

Over the course of his career, Murali twirled his country to 54 wins in 132 Tests, taking 795 Test wickets at 22; Sri Lanka's other bowlers in those games averaged 36. Even in the 23 Tests Murali missed during his career, his colleagues managed to average 37.

Not only was Murali a more than useful bowler himself ("probably better than Eddie Hemmings" – International Understatement Magazine, January 2008), but since his retirement, Sri Lankan bowling appears to have gone into a prolonged grump at the realisation that he has gone forever, subject to some major age-reversing advances in one or both of science and witchcraft.

In the words of Piglet's agent during a particularly heated argument over how to split the royalties from the latest Winnie The Pooh film, it has all been too much to bear. Boom.

Published on November 07, 2011 22:08

November 3, 2011

Match-fixing: where it all began

"As Butt, Asif and Amir disappeared into the unwelcoming bosom of the British prison system, the surgeon at St Cricket's Hospital woke the corruption iceberg from its anaesthetised slumber. The tipectomy had been successful. The iceberg was released back safely into the wild, and HMS Cricket sailed on serenely for evermore."

-- From A History Of Cricket, by Gervold H Scralthouse, published 2084

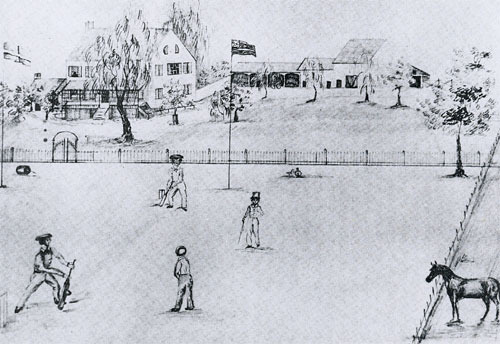

A drawing of the 1844 USA v Canada match reveals, rather suspiciously, that the only spectator present was a horse

© ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Perhaps these words will one day be written. Perhaps not. I hope this will prove to be a long-overdue watershed for cricket. Until now the sport has not entirely grasped the match-fixing bull by the horns. It has, to be fair, sent the bull a few sternly worded letters asking it to please remove its horns, or at least file them down a bit so they are not quite so pointy. But the bull appears to have not opened its post. Or has been unable to read.

It is all rather depressing for anyone who loves one or more of cricket, Pakistan, Pakistan cricket, or humanity in general. Open any newspaper, history book or heavily guarded government building and you will be confronted by story after story of greed, corruption, arrogance, dishonesty and the failure of human beings to resist the lure of easy money, all of which played starring roles in the Lord's 2010 debacle.

Look at the state of the global economy, and the unbridled avarice, short-termist recklessness and morally squalid practices that have left it lying face-down on the canvas, gasping for air and asking for its mummy; look at MPs convicted for fiddling expenses; at all manner of personal, corporate, commercial and national malpractices; at Allen Stanford and his Perspex box of pretend lucre. Sport is supposed to provide an escape from all that. But easy money is a persuasive salesman, and we now can add to that regrettable roll call of its customers the cream of third-millennium Pakistan fast-bowling.

I hope Amir has a future in cricket. I like the idea of redemption. I do not know how I would have reacted in the same situations, under those pressures, and in that dressing room. I like to think I would have had the strength to refuse. And I would probably have been more worried that my slow-medium long-hops and technical weakness with the ball against all forms and qualities of bowling might be shown up at international level. But if I had a captain, an agent, and a large wodge of banknotes all trying to persuade me to do something I thought I could probably do without compromising my ability to take 6 for 30 in 13 overs of mesmeric swing bowling, maybe I would have done it.

I hope not. I hope I would rather have taken 6 for 28, without the two no-balls. But I don't know. Situations like that did not crop up very often in my days in the West Kent Village League, and on the UK stand-up comedy circuit, gig-fixing is mercifully far from rife. At the moment.

Published on November 03, 2011 22:55

November 1, 2011

Multistat: 78.1

MS Dhoni's average in 96 innings in ODIs that India have won - the highest average by anyone who has batted more than 10 times in victorious ODI matches. In ODIs India has lost, the Ranchi Rampager averages just 28.4 (the 80th highest average by anyone who has batted more than 10 times in losing ODIs), giving him one of the highest runs-per-dismissal-difference-between-victories-and-defeats of any player in the history of the limited-over universe.

(By way of comparisons: since Dhoni's December 2004 debut, all ODI top-seven batsmen combined have averaged 42.5 in victories and 23.8 in defeats; Michael Bevan, who fulfilled a similar middle-order-finisher role for Australia, averaged 65 in wins and 40 in losses; and current South Africans Hashim Amla and JP Duminy heroically smash 70 and 64 respectively on the train to Triumphtown, but miserably plink just 26 and 17 when on the long road to Losersville.) In the mercifully-now-consigned-to-history ODI series against an alleged England side, Dhoni again proved himself one of ODI cricket's greatest finishers, an ice-veined abacus with forearms stronger than an elephant's hammock, a man who knows (a) where his accelerator pedal is, (b) when to press it, and (c) that his opponents know that he knows when to press it, and how hard he will press it when he chooses to do so. Dhoni has now batted in 47 successful chases, averaging 108 with a strike rate of 90, and he has been not out on , closing in on Jonty Rhodes' record of 33 opportunities to be the first batsman to pull a commemorative stump out of the ground at the end of a successful one-day pursuit. The Indian skipper has batted 36 times in unsuccessful chases, hitting five half-centuries, averaging 23, with a strike rate of 71. The massive divergence between his winning and losing averages suggests that Dhoni's wicket is almost as important to a bowling team in an ODI as lungs are to a racehorse. These averages need to be taken with a pinch of salt ‒ he bats lower down the order than most top batsmen, so his high average in successes is boosted by not-outs, and his low average in defeats is diminished because he often comes in having to take risks early in his innings. But that pinch of salt should merely enhance the flavour of the stat, rather than render it inedibly briny. Mmmm. Yum.

Also: The percentage of air made up of nitrogen. Dazzling England gloveman Jack Russell reportedly used to take his own supply of nitrogen on tour with him, in case the local nitrogen disagreed with him.

Also: The percentage of bananas rejected by England's Bodyline skipper Douglas Jardine for being "insufficiently banana-shaped". Jardine was convinced throughout his adult life that only 21.9% of bananas were up to scratch. He preferred bananas to Australians.

(By way of comparisons: since Dhoni's December 2004 debut, all ODI top-seven batsmen combined have averaged 42.5 in victories and 23.8 in defeats; Michael Bevan, who fulfilled a similar middle-order-finisher role for Australia, averaged 65 in wins and 40 in losses; and current South Africans Hashim Amla and JP Duminy heroically smash 70 and 64 respectively on the train to Triumphtown, but miserably plink just 26 and 17 when on the long road to Losersville.) In the mercifully-now-consigned-to-history ODI series against an alleged England side, Dhoni again proved himself one of ODI cricket's greatest finishers, an ice-veined abacus with forearms stronger than an elephant's hammock, a man who knows (a) where his accelerator pedal is, (b) when to press it, and (c) that his opponents know that he knows when to press it, and how hard he will press it when he chooses to do so. Dhoni has now batted in 47 successful chases, averaging 108 with a strike rate of 90, and he has been not out on , closing in on Jonty Rhodes' record of 33 opportunities to be the first batsman to pull a commemorative stump out of the ground at the end of a successful one-day pursuit. The Indian skipper has batted 36 times in unsuccessful chases, hitting five half-centuries, averaging 23, with a strike rate of 71. The massive divergence between his winning and losing averages suggests that Dhoni's wicket is almost as important to a bowling team in an ODI as lungs are to a racehorse. These averages need to be taken with a pinch of salt ‒ he bats lower down the order than most top batsmen, so his high average in successes is boosted by not-outs, and his low average in defeats is diminished because he often comes in having to take risks early in his innings. But that pinch of salt should merely enhance the flavour of the stat, rather than render it inedibly briny. Mmmm. Yum.

Also: The percentage of air made up of nitrogen. Dazzling England gloveman Jack Russell reportedly used to take his own supply of nitrogen on tour with him, in case the local nitrogen disagreed with him.

Also: The percentage of bananas rejected by England's Bodyline skipper Douglas Jardine for being "insufficiently banana-shaped". Jardine was convinced throughout his adult life that only 21.9% of bananas were up to scratch. He preferred bananas to Australians.

Published on November 01, 2011 02:13

Dhoni the winner v Dhoni the loser

78.1

MS Dhoni's average in 96 innings in ODIs that India have won - the highest average by anyone who has batted more than 10 times in victorious ODI matches. In ODIs India has lost, the Ranchi Rampager averages just 28.4 (the 80th highest average by anyone who has batted more than 10 times in losing ODIs), giving him one of the highest runs-per-dismissal-difference-between-victories-and-defeats of any player in the history of the limited-over universe.

(By way of comparisons: since Dhoni's December 2004 debut, all ODI top-seven batsmen combined have averaged 42.5 in victories and 23.8 in defeats; Michael Bevan, who fulfilled a similar middle-order-finisher role for Australia, averaged 65 in wins and 40 in losses; and current South Africans Hashim Amla and JP Duminy heroically smash 70 and 64 respectively on the train to Triumphtown, but miserably plink just 26 and 17 when on the long road to Losersville.) In the mercifully-now-consigned-to-history ODI series against an alleged England side, Dhoni again proved himself one of ODI cricket's greatest finishers, an ice-veined abacus with forearms stronger than an elephant's hammock, a man who knows (a) where his accelerator pedal is, (b) when to press it, and (c) that his opponents know that he knows when to press it, and how hard he will press it when he chooses to do so. Dhoni has now batted in 47 successful chases, averaging 108 with a strike rate of 90, and he has been not out on , closing in on Jonty Rhodes' record of 33 opportunities to be the first batsman to pull a commemorative stump out of the ground at the end of a successful one-day pursuit. The Indian skipper has batted 36 times in unsuccessful chases, hitting five half-centuries, averaging 23, with a strike rate of 71. The massive divergence between his winning and losing averages suggests that Dhoni's wicket is almost as important to a bowling team in an ODI as lungs are to a racehorse. These averages need to be taken with a pinch of salt ‒ he bats lower down the order than most top batsmen, so his high average in successes is boosted by not-outs, and his low average in defeats is diminished because he often comes in having to take risks early in his innings. But that pinch of salt should merely enhance the flavour of the stat, rather than render it inedibly briny. Mmmm. Yum.

Also: The percentage of air made up of nitrogen. Dazzling England gloveman Jack Russell reportedly used to take his own supply of nitrogen on tour with him, in case the local nitrogen disagreed with him.

Also: The percentage of bananas rejected by England's Bodyline skipper Douglas Jardine for being "insufficiently banana-shaped". Jardine was convinced throughout his adult life that only 21.9% of bananas were up to scratch. He preferred bananas to Australians.

Published on November 01, 2011 02:13

October 26, 2011

Six questions arising from the India-England series

The case for Jonathan Trott: dropping him is as pointless as every episode of Jackass

© Getty Images

I'm confused. England crunched India like a birthday biscuit in the Tests during the summer, then beat them conclusively in the one-day series. But now, just weeks later, they have been unceremoniously counter-crunched by the same opposition, honked 5-0 in a fiesta of grumpy ineptitude, by an Indian team that was as focused, calm and efficient as it wasn't in England. What does it all mean?

It is too early to say definitively. I think we can safely say that, on the evidence of this series, England will struggle in the 2011 World Cup. Subcontinental conditions do not suit their game. India, meanwhile, will be desperately trying to remember not to begin the 2019 World Cup in England (a) with much of their first-choice side absent, (b) after a long, exhausting and humiliating tour that followed hot on the heels of another Test series, the IPL and a World Cup, and (c) in a rainy September.

It is probably also fair to say that England have not entirely cracked ODI cricket yet, but that MS Dhoni has.

Does it matter that England's batsmen keep getting out after making a start?

Strap in, stats fans, I've been digging again. Don't tell the wife. (I'll give you a couple of paragraphs to brace yourselves for the stat. Gather your family round, I think they should all be told.)

On a global scale, humanity probably has more significant issues to address than England's batsmen playing themselves in and then playing themselves out again with alarming rapidity. And for Britain as a nation, this matter resides below staving off economicageddon, wondering if we can start exporting our old people to ease the pensions problem, and bickering over whether we should leave Europe and catapult ourselves into the mid-Atlantic instead. However, in the realm of one-day cricket it certainly does matter.

In Mohali, Ravi Bopara played arguably the archetypal modern England ODI innings – 24 off 32. It was not a dismal failure, but it was as close to unhelpful in the circumstances as he could have managed. Admittedly England could have done with a few more archetypal 24s off 32s in Kolkata yesterday, but of the impressive selection of Achilles heels they have flashed at the cameras during this series (historians are reassessing whether Achilles was in fact a centipede, not a man), the infuriating habit of batting quite well for a bit and then getting out was the most swollen.

STAT ALERT. Here it comes. It's about batsmen getting out in the 20s and 30s. 5-4-3-2-1. Blast Off.

In ODIs since the end of the 2007 World Cup, top-seven England batsmen have been out between 20 and 39 on 152 occasions, compared to the 196 times that they have gone on to reach 40. So 43.7% of the times an England batsman has reached 20 (and has not finished not out between 20 and 39), he is out before he reaches 40. Of Test-playing nations in that time, England are only sixth best at top-seven batsmen not getting out in the 20s and 30s, just behind New Zealand (43.4%). The top four is as follows: South Africa in first (32% dismissed between 20 and 39), Australia in second (36.7%), India in third (38.5%), Sri Lanka in fourth (39.5%).

In this period, the highest ODI win percentage table is: South Africa in first (68.1%); Australia in secnd (67.7%), India in third (62.7%), and Sri Lanka in fourth (57.3%).

Have a glass of water.

Published on October 26, 2011 22:23

October 18, 2011

When Boycs made Packer giggle

440

Number of balls faced by Geoffrey Boycott in in 1978-79. How many did he hit over the boundary rope for four? (a) 439 - he really went for it after being knocked unconscious at breakfast on day one when Ian Botham unexpectedly flang a croissant at him at high speed; (b) 5 - not exactly bums-on-seats batting, more bums-off-seats-to-go-to-the-bar-for-a-beer-to-numb-the-pain batting; or (c) 0 - what had the boundary rope ever done to him? Why should he inconvenience it by sending a ball hurtling towards it?

Think about your answer carefully. No conferring.

Concentrate.

Pens down. The answer is - brace yourselves, Twenty20 fans ‒ (c) 0. In nine hours 42 minutes of batting, the Yorkshire legend managed a solitary all-run four. The Packer-ravaged 78-79 series was by no means Boycott's career highlight - he averaged fractionally , his strike rate was fractionally over 22, and, in all, he smote five scintillating boundaries in more than 24 hours at the crease - fractionally more than one fence-blasting hammer-blow per day's play. In fact, if a team made up entirely of 1978-79 Boycott clones batted at both ends for an entire 90-over day, they would end on 122 for 5. And all this happened to the lilting background tones of Kerry Packer giggling wildly to himself and asking, "Anyone want to watch some guys in silly clothes whacking it about a bit?"

Boycott proudly resides in third place in the slowest-recorded match-scoring rate of anyone who has faced at least 400 balls in a Test - narrowly behind Brearley's defiantly strokeless 17 off 64 and 74 off 344 against Pakistan in 1977-78, but way adrift of the career masterpiece of the Plato of Plod himself, Trevor Bailey, who brought humanity to the precipice of spiritual permafrost in scoring 27 off 116, followed by 68 off 427 (match figures of 95 runs off 543 balls, equivalent to two entire days' batting in a modern Test, and a strike rate of 17) at the Gabba in 1958-59.

It is now widely accepted by experts that it was Bailey's second innings, rather than competition with the Soviet Union, that prompted America to invest heavily in space travel, in order to offer the people of the world a viable escape route from having to witness similar innings in future.

Also: The percentage increase in sales of coffee reported by hot drink stalls at the Perth Test in 1978-79 whilst Geoff Boycott was at the crease.

Also: The percentage increase in sales of champagne reported by bars at the following Test after Boycott was out 13th ball for 1.

Published on October 18, 2011 02:09

Andy Zaltzman's Blog

- Andy Zaltzman's profile

- 12 followers

Andy Zaltzman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.