Andy Zaltzman's Blog, page 6

May 29, 2012

Boring, boring England

England: nowhere near the glory days of the 1980s

© PA Photos

Another home Test, another thumping victory for England, another surgical cauterisation of a visiting top order hopelessly ill-equipped and under-trained for the challenge of facing a remorseless, varied, high-class bowling attack. Another Test in which West Indies played well in patches, but against opponents with superior batsmen, bowlers, fielders, experience, facilities, funding, organisation, depth of talent, technology and any other facet of the sport you can imagine on and off pitch, they also played badly in patches, and were duly hammered. Another Test in which almost nothing was learnt.

One of the problems with the current England side is that, in their home series at least, they give journalists so little to write about. Long gone are the days when five or six places in the Test team were constantly up for discussion, and when you imagined the selectors sitting in a secret vault at Lord’s, literally sharpening their swords, whilst a grainy television showed a replay of Malcolm Marshall bowling an unplayable 90mph outswinger to a county journeyman speculatively catapulted into the Test team, whilst muttering: “Hutton would have hit that for four. Let’s try someone else. Pass me the county scorecards from the Times, my blowpipe, my lucky dart, and my blindfold made from Gubby Allen’s jockstrap, and let’s see who we come up with for Headingley.”

Nowadays there are meagre scraps to feed on when reporting on England’s home Tests, and some of those scraps turn out to be mirages, hallucinated by copy-famished writers. “Strauss under pressure as captain” ‒ he had lost one series in ten and had put in some below-average, but not disastrous, batting performances. “Bresnan’s place under the microscope” ‒ he had bowled only adequately in one match, and some people seemed to have either forgotten his return of 29 wickets at 18 in his previous six Tests, or regarded it as a fluke, or decided it was not as good as Sidney Barnes would have managed, and therefore open to criticism.

Now Bairstow needs to refine his game in country cricket because he struggled with a blistering throat ball from Roach when new at the crease, then played some more short balls quite well before getting out a bit oddly. Given that ten of the starting XI are basically inked in for the rest of the summer, assuming they maintain fitness and resist the temptation to ride a jetski down the Thames during the Queen’s jubilee flotilla and moon at the monarch, it is inevitable that Bairstow will receive considerable critical attention.

He might come good, he might not. He is 22, young for an England batsman – since Gower and Botham made stellar starts to their careers in their early 20s, only Cook and, to a lesser extent, Atherton, have had significant success under the age of 24.

The only way that any speculation about the bowling line-up can be engendered is by discussing whether the first-choice men need resting from their only Test match for the next seven weeks. Perhaps they need the full seven-week break from the five-day game, rather than just the five weeks they will have if they do play in the third Test. They will not want to rest. Particularly if Barath, Powell and Edwards are still the West Indian top three.

Compare this with the situation a couple of decades ago. Then, the cricket itself often seemed on the undercard to the incomprehensible game of selectorial rodeo poker that went on between the Tests. Graeme Hick seemed to have overcome his painful early struggles in Test cricket when he made his maiden hundred in India in 1992-93 ‒ a superb 178 after coming in at 58 for 4 in Bombay. He was dropped three Tests later, after the disastrous second-Test thrashing in the 1993 Ashes, in which he scored a respectable 20 and 64. He had scored a century and three 60s, and averaged 52, in his previous five Tests. All of which England had lost. It must have been his fault. How the selectors must have giggled.

Hick was recalled for the sixth Test, scored a brilliant 80 in a surprise victory, and proceeded to average in the high-40s for the next couple of years, against a series of top-quality bowling attacks, before everything went bafflingly pear-shaped again. Perhaps he had stumbled into that secret Lord’s vault in the 1993 Test, and never shook the uneasy feeling that the England selectors’ preferred method of keeping their players on their toes was to intermittently fire a pistol at their feet. Perhaps not. It is certainly true that Hick, Ramprakash and Crawley, England’s three greatest unfulfilled talents of the 1990s, were all crassly handled at various formative times of their careers, and if Cook and Bell had been playing in the 1980s or 1990s, they would each have been dropped about ten times by the current stage of their careers. As it is, England largely stuck with them through some relatively mediocre times, and have been rewarded by them eventually maturing into insatiable run machines (give or take the odd jaunt to the subcontinent).

Another victim of the random almost Soviet-style justice dispensed by the England selectors in the early-to-mid 1990s was Graham Thorpe. He replaced Hick for the third Test in 1993, scored a debut century, then 37 and 60 in his third Test – against Hughes, Warne, May et al ‒ before, following a difficult start in the West Indies early in 1994, he scored a couple of outstanding 80s against a tidy pace attack of Ambrose, Walsh and two Benjamins. He had come through his early examinations with merit. And was promptly presented with a certificate telling him that he had failed. Next up: a limited New Zealand, at home. Thorpe was dropped. (And please bear in mind that, compared with large swathes of the 1980s, the selectors had calmed down considerably.)

It must have been an awesome time to be an English cricket scribe. You could champion a county player in the confident knowledge that he would probably at least be discussed as an England possible; you could question an incumbent, knowing that one below-par match was enough to get the selectors reaching for their bolt-gun of mercy. You must have felt like a Greek god, toying with human chess pieces.

But now – nothing. Central contracts, sound management, persistent collective and individual success have rendered the job of the press-box scribbler rather grey in these mostly disappointing early-summer series. How many different ways are there to write “He played another good innings”, or “He bowled well again”, or “The opposition were not at their best”?

Published on May 29, 2012 20:39

May 24, 2012

Multistat: 588

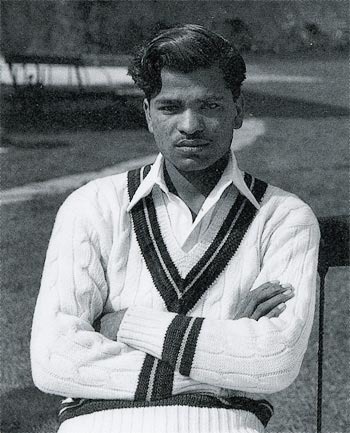

After the Egdbaston Test of 1957, Ramadhin learnt that it's better to keep your hands to yourself than than involve them in ball-flinging

© The Cricketer International

West Indies’ total runs in the match at Lord’s – the joint second-highest match total that England have conceded in their last 23 Tests, since Bangladesh scored 282 and 382, also at Lord’s, two years ago.

In this golden period for English bowlsmanship, the only time an opposing team has scored more against them than Darren Sammy’s team did at Lord’s was Sri Lanka, who totalled 606 for 13 last year, also at the Home of Cricket. In England’s previous 20 Tests, from December 2008 to May 2010, they had conceded more than 606 on 13 occasions.

It has been an extraordinary display of sustained excellence, illustrated by the fact that, since May 2010, all eight specialist bowlers who have played Tests for England have averaged under 27 (if we exclude Samit Patel from the list of specialist bowlers) (which does not seem entirely unfair).

Over the previous two years, 13 bowlers played Tests for England. None of them averaged under 27. And only one (Graeme Swann, 29.6) registered under 30.

In April 2010, David Saker was appointed England’s bowling coach. Well done him. Perhaps he should be placed in charge of the European economy.

Also: The most balls any bowler has sent down in a single Test innings.The unlucky/exhausted/annoyed/regretful-of-ever-picking-up-a-cricket-ball man was West Indian legend Sonny Ramadhin, in first Test of the 1957 series in England, when he finished with (a) soul-sapping second-innings figures of 98-35-179-2, (b) sore fingers, and (c) a lifelong hatred of the words “over bowled”.

It had all begun promisingly for the Trinidad Twirler ‒ he skittled England in the first innings, taking a career-best 7 for 49 in 31 overs, before putting his feet up for a couple of days as West Indies built a lead of almost 300. That was his tenth five-wicket haul in 29 Tests, and his tally against England stood at 56 wickets in 9½ Tests, at an average of 21.6. “I’ve got these guys on toast,” he must have thought to himself. “In the second innings, I’ve going to slice them into soldiers and dip them in an egg.”

Sonny then dismissed Peter Richardson and Doug Insole in quick succession early in England’s second innings, taking him to nine wickets in the match. “A nice shiny ten-for coming right up,” he could have been forgiven for thinking at the time. And for continuing to think, with gradually decreasing optimism, for the remaining ten hours of England’s innings, as he sent down more than 80 wicketless overs in the face of a record-breaking rearguard by Peter May and Colin Cowdrey, who added 411. May declared with Ramadhin still one tantalising wicket short of his ten for the match, and the game ended with the aching spinner nervously padded up in the pavilion, after West Indies collapsed to 72 for 7.

Ramadhin, who had befuddled England throughout the 1950s, had finally been defused. He took a not-entirely-grand total of one wicket in the next three Tests, before taking four (including a couple of tailenders) in a walloping innings defeat at The Oval. He never took another Test five-for, and his record against England, from the start of that painfully distended Edgbaston tweakathon to the end of his career three years later, was 24 wickets in 8½ Tests, at an average of 41.2.

Conclusion: Bowling 98 overs in an innings can seriously damage your health.

EXTRAS

● West Indies’ over-rate in England’s mammoth second innings in that 1957 Test was around 22 per hour. That’s 22 overs per hour. Let me repeat that for any younger readers (below the age of around 40) who assume that must be a misprint. Twenty two overs per hour. According to reliable sources, overs were still six balls long in 1957, and, despite post-war austerity, hours still mostly lasted 60 minutes, as they do today.

I went to Lord’s on the third day of this year’s Test. It was an intriguing day’s play, it took two hours 30 minutes to bowl the first 30 overs. That is 12 overs per hour. Let me repeat that for any older readers who have not been watching cricket for the last 40 years. Twelve overs per hour.

Admittedly, in 1957, the game was not slowed down quite so much as it now by extraneous interventions such as: DRS referrals; needless advertiser-appeasing drinks breaks on cool, cloudy-days, after drinks have been brought out anyway at every available break in play (and some unavailable breaks in play); umpires waddling around so slowly that it appeared they were trying not to disturb a rare breed of puffin that had nested in their hats; Ian Bell repeatedly not being ready to face Fidel Edwards despite Edwards having sauntered the 30-odd yards back to his marker as if walking deliberately slowly to an unwanted dentist’s appointment; and armies of 12th, 13th and 14th men in natty high-visibility tabards jogging on to the pitch at every available opportunity to provide England’s batsmen with (more) drinks, previously undiscovered bits of kit, personal financial advice, "Congratulations On Still Being At The Crease" cards, updates from their Twitter feeds and/or the Leveson Inquiry, a run-down of the local take-away options in case lunch proved to be a disappointment, limericks, crossword clues, shoulders to cry on, the latest gossip from whatever TV talent show is on at the moment, sundry other items required by 21st-century 12th-man duties, and horse-racing tips (the most reliable of which I have always found to be: point it forward and tell it to run fast).

But still. Twelve overs an hour. In an age when players are physically fitter than ever. It’s ridiculous, completely unnecessary, and, given the price of tickets that spectators had bought in the naïve hope of seeing 90 overs in the day, tantamount to mild larceny.

● Here’s another stat for you that further highlights England’s excellence with the ball. Remember it well. It’s guaranteed to break the ice at parties. In 11 innings this year, England have allowed the opposition’s second wicket to add a total of 107 runs – 9.72 per partnership. Since the hooter sounded to mark the end of the First World War in 1918, only once has a team taken its opponents’ second wickets more cheaply in any calendar year in which they have played at least three Tests – Australia, in 1958, who conceded just 51 runs in nine second-wicket stands (5.66 per partnership).

West Indies’ No.5 Shivnarine Chanderpaul, magnificent player and supreme batting craftsman that he is, can say all he likes about young players only being able to learn the Test game by batting at the top of the order, but (a) he is obviously wrong, and (b) there is only so much learning they can do sitting in the pavilion watching the ball get older.

Published on May 24, 2012 20:54

May 14, 2012

The Sobers-Kallis debate resolved for the final time ever

Andy Zaltzman goes where no man has gone before to get stats that prove who the world's best allrounder is, while also finding time to answer other readers' questions.

Download the podcast here (mp3, 14.3MB, right-click to save).

iTunes

Download the podcast here (mp3, 14.3MB, right-click to save).

iTunes

Published on May 14, 2012 23:28

May 5, 2012

The fate of West Indies and the Rolly Janglers

On this tour of England, Darren Sammy will hope to need his umbrella more often than Mary Poppins did

© PA Photos

The West Indies must have arrived in England in confident mood for their three-Test tour, buoyed by optimistic historical precedent. They would have read that England is, officially, in the midst of a drought ‒ and thought instantly of the sun-baked summer of 1976, when the parched outfields of this land were scorched by the blazing strokeplay of Viv Richards, Gordon Greenidge and Roy Fredericks, and by the scurrying footsteps of England’s batsmen fleeing to the pavilion after being volcanically obliterated by pace of Andy Roberts and Michael Holding. “This could be our year,” they must have thought as they flew across the Atlantic. “Ignore all the form lines, Dr Drought could swing it for us.”

They landed a few days ago to find a country thoroughly marinated by rainwater and ensconced in thermal underpants, with Worcestershire County Cricket Club looking over the New Road outfield and anxiously checking eBay listings for an affordable-looking ark. This is not the most obviously droughty of droughts. If the current West Indies batting line-up – into which Greenidge and Richards must have been close to being recalled, despite being in their sixties ‒ rack up 687 for 8 declared in a damp green-pitched early-season series, as the 1976 vintage did on the brown-grassed desert of The Oval, with Richards scoring an unmatchably majestic 291, then suspicions may arise that Allen Stanford’s accountant has been operating the scoreboard.

For one of the 1980s West Indian touring parties to have lasted an entire day without losing a wicket, or indeed without conceding a run, against county opposition, would barely have raised an eyebrow. However, in 2012, yesterday’s wash-out against Sussex will not have helped Darren Sammy’s alarmingly inexperienced and institutionalised-bickering-depleted batting line-up to learn about the unfamiliar conditions that face them.

That is one of the six days of cricket before the first Test already washed down the plughole of history. Narsingh Deonarine’s and Assad Fudadin’s acclimatisation period has been further curtailed by visa problems delaying their arrival. (If only English cricket had formulated this cunning strategy when Bradman first toured here in 1930. “I’m sorry Mr Bradman, but your visa application has been rejected. Why? Er, well, it’s because we have reason to believe you have links to Al-Qaeda. Can’t go into details, Official Secrets Act. Off you pop. See you in the Bodyline Series.”)

Published on May 05, 2012 23:54

May 2, 2012

When Chanders went bonkers

Shivnarine Chanderpaul accepts trophies on behalf of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

© AP

The engrossing 2011-12 Test season came to an end last week, as Australia sealed a 2-0 win in the West Indies. The series could have had a different result had West Indies not been undermined by IPL clashes, selectorial squabblings, and top-order batting with the solidity of a blancmange in a 1950s nuclear-weapons test. History will probably judge those three factors to have been interlinked.

Standing defiantly amidst the wreckage was Shivnarine Chanderpaul, the best batsman in the series by a significant margin, who became the tenth batsman to pass 10,000 Test runs, returned to the top of the Test batting rankings, and edged his career average back over 50. There may be few cricket lovers who drift off to sleep at night fondly reminiscing about the day they saw Chanderpaul stroke the ball effortlessly around the park, but he has been one of the most remarkable batsmen in an age of remarkable batsmen, a craftsman of infinite resource, capable of breaking out of his physics-defying stance with outbursts of truly sublime timing.

Chanderpaul will be remembered primarily as a dogged accumulator, but he was responsible for one of the most extraordinary innings ever played in Test cricket. On day one of the April 2003 Test against Australia in Guyana, he came to the wicket with West Indies wallowing in an especially sludgy mire at 47 for 4. Lara was soon dismissed at the other end to make it 53 for 5.

Chanderpaul, ever the man for a crisis, might have been expected to try to graft his team towards a moderate total. Instead, he plumped for an unexpected Plan B – he hammered a 69-ball century, batting as if someone had spiked his morning cornflakes with industrial-strength fireworks, and flaying the Australian bowling attack as if he had just discovered they had each eaten one of his beloved squad of pet terrapins, leaving behind only empty shells graffitied with the word “yum”.

For a man with a career strike rate of 40, who less than a year before had ground his awkward way to 136 not out off 510 balls in an 11-hour megavigil against India, to slap what was then the third-fastest Test hundred of all time against the world’s No. 1- ranked team has to go down as one of the most out-of-character innings in Test history. He has compiled some of the most remarkable individual series performances of recent times, but that one innings stands out on his CV like a freshly powerdrilled thumb.

At the other end of the “What on Earth Got Into Him?” scale of out-of-character batsmanship is Aravinda de Silva’s epically unproductive performance against Zimbabwe in Bulawayo in October 1994. He followed a 14-ball first-innings duck with a staggeringly negative 27 off 191 balls ‒ the second-slowest recorded innings of 25 or more in Test history ‒ as Sri Lanka ground their way to a draw on the fifth day. It must have felt like watching Michelangelo paint a chapel ceiling in an especially featureless shade of beige.

Only Jack Russell’s unbeaten 29 off 235 in Johannesburg in 1995-96 ‒ the Robin of Resistance to Atherton’s Batman of Block ‒ has ever out-turgided de Silva’s innings, and that was an innings that was certifiably in-character, a magnum slow-pus by one of cricket’s most infuriating batsmen.

De Silva, on the other hand, was a cavalier and magician, one of the most bewitching batsmen of his era, capable of destroying the best attacks while under the utmost pressure, in a flurry of untouchable strokeplay. In Bulawayo, the cavalier became a roundhead, and the magician downed his magic wand, gave his rabbits the day off from appearing out of his top hat, and did his accounts.

Furthermore, he was up against a bowling attack none of whom had taken more than 16 Test wickets. And three of whom (Jarvis, Rennie and Peall) were so traumatised by the ordeal of bowling to him that they played a combined total of two more Test matches and took a collective one further Test wicket in the rest of their careers.

Behind de Silva on that list of epic grinds are some of the all-time legends of strokeless negativity ‒ Chris Tavaré (35 off 240), Trevor Bailey (68 off 427), Trevor Franklin (28 off 175), and the renowned snooze-inducing West Indian stodgemeister, Chris Gayle.

Hang on, is that the same Chris Gayle widely regarded as the best Twenty20 batsman in the loud history of the format? The Chris Gayle who hit a 70-ball Test hundred? Who flambéed 117 off 57 balls to register the first-ever century in a T20 international? Against South Africa? Who is third on the all-time list of Most-Sixes-Clonked In International Cricket? Who is one of only two players to have twice hit seven or more sixes in a Test innings (the other being Chris Cairns)? Who in his last two IPL matches has chunk-hammered 86 off 58 and 71 off 42, hitting one in every ten balls over the ropes and endangering innocent passers-by in the streets of Bangalore with his leviathan power? The Chris Gayle who can make bowlers inwardly beg for their mummies with one muscular flick of the shoulder? Yes. That Chris Gayle. That very same Chris Gayle.

In April 2001, early in his Test career, at the end of a testing series against South Africa, as West Indies battled towards a consolation fifth-Test victory against the potent Protean pacemen, Gayle anti-bludgeoned his way to a sub-Boycottian 32 off 180 balls. It remains the slowest Test innings of 25 or more ever played by a West Indian. If he batted at the same rate in the IPL, he would carry his bat for 11 not out.

Gayle did not find Test cricket an easy game in his early years. In his first 20 Tests he averaged under 30, and it was only in his 37th Test that his strike rate rose above 50. If he found Test cricket difficult then, however, now, he finds it impossible. Albeit for off-the-field reasons. Which is deeply regrettable. In what seem likely to prove his final 18 Tests, between December 2008 and December 2010, Gayle averaged 58, and hit 36 sixes.

Would England rather be bowling at Adrian Barath and Kieran Powell when the first Test begins at Lord’s in two weeks’ time? Was Don Bradman good at batting? And would world cricket rather be watching England bowl at Gayle? Ditto.

● Strap in for some curious stats. Since Brian Lara retired from Tests at the end of 2006, Chanderpaul has averaged 66 in Tests – the highest average of any Test batsman over that period. In the matches he played with Lara, Chanderpaul averaged 43. Was he cowed by Lara’s presence?

Lara, in Tests when he played alongside Chanderpaul, averaged 47. In all the Tests he played without Chanderpaul in the team, Lara averaged 62. Was he cowed by Chanderpaul’s presence? Maybe each was inspired by the extra responsibility of not being able to rely on the other. Maybe it is just coincidence. Maybe not.

Conclusion: West Indies should have played and dropped Lara and Chanderpaul in alternate Tests throughout their careers. Leaving out one of their two best players every match might not have been especially popular with the supporters, or with Lara or Chanderpaul, but you cannot argue with statistics. In any case, West Indian cricket has recently shown a relentless determination not to pick its strongest team anyway, so it might as well have done so from the mid-1990s.

Published on May 02, 2012 21:01

April 23, 2012

Questions from the kids, and a bit about Jaisimha

“Daddy, why does that man have no sartorial sense?”

© AFP

Thank you for your responses to last week’s blog on English interest in the IPL, which provoked some lively and varied reactions. Some agreed with my viewpoints, others did not. Some in a more strongly worded manner than others. Several Indian readers expressed a similar lack of emotional connection with the tournament, some from elsewhere in the cricketing world have fallen for the new-fangled charms of the talent-packed short-form spectacular.

The IPL continues to be the biggest issue in the game at the moment. It clearly arouses strong and divergent opinions, in India and outside. I do not, however, think there is any element of “English jealousy” involved. Test match fans the world over – whether they love, hate, or remain undecided about Twenty20 as a format ‒ are rightly concerned about the impact it is having, and will inevitably continue to have, on the game they love. Its effects have already been seen in international schedules, team line-ups, players’ techniques, and the volume and unchangeability of the excitement in the voices of stadium announcers.

Clearly, T20 and the IPL have done and will do much good for the game globally. They could also, in some ways, do irreparable harm. The balls are, literally and metaphorically, up in the air, swirling around in the floodlights after cricket took an almighty swish with its eyes partially closed, and we do not yet know if those balls will land safely pouched in our hands, splash messily into our plastic beer glasses, or plummet hard and fast straight on the bridge of our cricket-loving nose. Or a combination of all three. The anxieties many people have about the future of the game are nothing to do with national affiliation.

A final footnote to last week’s piece (which, I would like to stress, I did not intend to be an “anti-IPL” piece, still less an “anti-Indian” one, nor do I think it was one)… During my children’s supper time on Monday evening, we watched the closing stages of the republican-minded IPL fan’s nightmare match-up between Royal Challengers Bangalore and the Rajasthan Royals, won easily by Bangalore after some characteristically brilliant striking by the Virtuoso of the Veldt, AB de Villiers.

My children, aged five and three, asked a range of questions of varying pertinence, from “Is he out?”, “Why has that man got big gloves on?”, and “Why do the blue team keep hitting the ball in the air?”, to “Whatever happened to getting your foot to the pitch of the ball, keeping your front elbow high, and stroking the ball along the ground?” (The last of those questions may, on reflection, have been asked not by my offspring but by the ghost of Gubby Allen, who had popped round unexpectedly for a cup of tea and a quick haunt.)

With a few overs remaining, my daughter chose to support the Royal Challengers, largely because I told her they were by this stage definitely going to win, but partly also because I had been to Bangalore. We have therefore picked the RCB as our team for the rest of the tournament, thus giving us the not-quite-umbilical emotional connection to an IPL franchise that I wrote about English viewers generally lacking. I am taking her to the tattoo parlour tomorrow morning to have a portrait of Vinay Kumar inked indelibly onto her bicep. Whilst I go into surgery to attempt to have my hair rendered as gloriously luxuriant as Zaheer Khan’s. It may be a long operation.

These early encounters with cricket can prove deeply influential – my children may well grow up thinking that RCB’s four-wicket hero KP Appanna is the greatest bowler in the history of the game, just as I grew up convinced that Chris Tavaré was the inviolable blueprint for the art of batsmanship.

After supper, we retired to the children’s bedroom, armed with a plastic cricket bat and ball, and for the first time in their young lives, the junior Zaltzmans showed genuine interest when their daddy tried to make them play cricket. My son displayed a penchant for leg-side drives that can only have come from his mother’s side of the family (if he had sliced everything through gully, any paternity issues would have been verifiably laid to rest), whilst my daughter clonked a straight six ‒ all the way to the curtain on the other side of the room, a mighty carry of some 10 or 12 feet ‒ of which Ian Botham himself would have been proud. If their strokeplay was a little on the agricultural side of the MCC Coaching Manual, their youth and inexperience can probably be held responsible more than the IPL hoicking they had just been watching.

Would the same youthful enthusiasm have been created if I had switched over to the West Indies v Australia Test match? Probably not. The children’s questions would certainly have been different – “Why aren’t they hitting the ball in the air?”; “Whatever happened to the concept of risk-taking initiative in Australian batsmanship?”; “Why are both teams wearing white?”; “Why are you so interested in this, daddy?”; and “Why isn’t Chris Gayle playing?” To all of which, the answers would have been: “It’s complicated, darling. It’s complicated. Eat your broccoli.”

Published on April 23, 2012 22:29

April 19, 2012

Am I wrong in not caring about the IPL?

Former South African and former Royal Challenger from Bangalore, and current Delhi Daredevil Kevin Pietersen shakes hands with former Royal Challenger and current South African and Deccan Charger Dale Steyn. Keep track people, it’s a question of loyalty

© AFP

Kevin Pietersen clobbered his first Twenty20 hundred yesterday, clinching the match for the Delhi Daredevils, and passing three figures with a characteristic six. It was a startling innings by a startling player, although startling things happen so often in the IPL that their startle capacity is less startling than you might expect of cricket so startlingly startling.

Last week Pietersen, who is admirably open, passionate and forthright in his media utterances, bemoaned the lack of English interest in the IPL, and the sometimes negative publicity it receives in the press here, attributing some of these problems to “jealousy”. From the selected quotes reported, it is hard to know who is supposed to be being jealous of the IPL – ex-players in the media who missed out on its glamour and financial bounty, or supporters who feel it takes the sun-kissed multi-million-dollar glitz and glory away from the April skirmishes in the County Championship, or the prime minister, who secretly wishes he was an IPL dancing girl.

However, the reason for any lack of English interest in the IPL is simple. It is not because the “I” stands for Indian. The same would be true if it was the Icelandic Premier League or the Idaho Premier League. More so, probably. Idaho has no business muscling in on cricket. They have snowmobiles and processed cheese. They should leave cricket well alone.

Nor does this relative lack of interest have anything to do with the format of the cricket and England’s general national preference for the longer game. Nor does it reflect on the quality of play, which although variable (as in any league in any sport), is often spectacular and dramatic. Nor even is it because the rampant hype and commercial insistence of the IPL might grate with a sport-watching public unaccustomed to having branded excitement blasted into their faces with the relentless determination of a child who has just discovered the joys of banging an upside-down cereal bowl with a spoon.

It is simply that, in an already saturated sports-watching market, the IPL does not, and I would argue cannot, offer enough for the English fan to actively support.

As a sports fan, you cannot force an instant emotional attachment to and investment in a team with which you have no geographical or familial link, and which has little history or identity with which to entice you. A Mongolian football fan might support Barcelona, or a Tanzanian baseball nut could develop a passion for the New York Yankees, for what those clubs are, what they have achieved, and what they stand for, and be drawn into their historic rivalries that have evolved over 100 years or more; but an English cricket fan is, as yet, unlikely to find the same bond of attraction to the five-year-old Chennai Super Kings. Supporting sport requires more than guaranteed entertainment and being able to watch great players competing.

Perhaps, in time, this will develop. The process was probably not helped by the franchise teams being largely disbanded and reconstituted before the 2011 season, so that any identity that had been built in the first three IPL seasons was fractured or destroyed.

It is also not helped by the fact that the star players might represent three or four different T20 franchises, and a country if time allows, over the course of a year. What if I love the Barisal Burners but am non-committal about the Sydney Thunder, scared of the Matabeleland Tuskers, unable to forgive Somerset for a three-hour traffic jam I sat in on the M5 ten years ago, and absolutely viscerally hate the Royal Challengers Bangalore (how dare they challenge our Royals, in Jubilee year especially) (despite any lingering historical quibbles)? What am I supposed to think about Chris Gayle? Is he hero or villain?

English cricket fans, even if sceptical or ambivalent about Twenty20, can admire the range of skills on display, appreciate how the format is expanding human comprehension of what mankind can and will do to small round things with flat bits of wood, and relish the high-pitched drama and tension of the endgames. They can simply enjoy seeing dancers jiggle their jiggly bits for no obvious reason, and be moved and uplifted by the sensation that unbridled commercialism is slowly destroying everything pure about sport and the world.

But, without teams and identities for which English supporters can root, and thus the emotional commitment that makes supporting sport such an infinitely rewarding experience, the IPL will continue to struggle to find active support in England. Not that the IPL, or Pietersen, or any of its other players and protagonists, should give two shakes or Billy Bowden’s finger about that.

I’d be interested to know your views on this, from English, Indian and other perspectives. I love cricket. I think I have probably made that abundantly clear in the three and a half years I have been writing this blog, and in the 30 years I have been boring my friends and, latterly, wife about it. I have tried watching the IPL, I have enjoyed some of it, but it just does not excite me. Am I normal, or should I see a shrink?

Published on April 19, 2012 23:57

April 9, 2012

The England puzzle, and the case for/against Sammy

Darren Sammy: he's a Star Trek character, he's not

© Getty Images

The dust is settling on England's fascinating, and, until Colombo's belated redemption, spectacularly unsuccessful Test winter. And that dust is confused. Very confused. Is it covering a landmark underachievement, or an unfortunate blip? Has 2011-12 shown how vulnerable this supposedly world-leading England side is, and how the weaknesses in it had been camouflaged by an unprecedented collective burst of form and some fractured, sub-standard opposition; or has it strangely proved, as suggested by my World Cricket Podcast compadre Daniel Norcross, quite how good they are?

They were, after all, not far from winning four Tests out of five despite having batted for most of the winter like a long-forgotten salad in an abandoned fridge, and they bowled persistently superbly (statistically far better than in 2000-01, when they returned from Asia with two series victories). As soon as the batsmen for the first time applied themselves correctly, they waltzed to a resounding victory. Albeit that the sound that resounded was the echo of the words, "Where the hell was that in the Gulf in January?" rebounding back from outer space.

So many questions remain to be answered. Which was the batting blip – the first four Tests or the last one? Will the Pakistan whitewash remain a scar on this excellent England team's record, or will it prove to be an open wound in which the maggots of doubt have laid out their towels for an interesting year's sunbathing ahead?

Your witness, history. Get back to us in nine months' time with some supporting evidence from (a) this summer's series against an increasingly-determined-but-almost-entirely-unacquainted-with-early-season-English-conditions West Indies, and a probably-should-be-No. 1-side-in-the-Test-world-if-only-they-didn't -keep-tanking-one-nil-series-leads South Africa, and (b) the four Tests in India at the end of the year.

Personally, my expectation is that England will beat West Indies comfortably, draw 1-1 with South Africa, and win narrowly in India, guided by their freshly printed multi-volume Encyclopaedia Of Lessons Learned, which they are no doubt busy scribbling down from their failures this winter.

However, my expectation was that they would win in the UAE against Pakistan, and they managed to avoid doing that in some style, in much the same way that the Titanic managed to avoid overshooting America on its maiden voyage.

And, just as they had not faced high-class spin for a lengthy period before subsiding to Ajmal and Rehman, so they will not have faced the calibre of swing bowling they can expect from Steyn and Philander since Amir and Asif brilliantly hooped them to distraction two years ago before. Just as facing Xavier Doherty in Brisbane, or Mishra and Raina at The Oval, was not ideal preparation for encountering Pakistan's crafty tweakmen in the Gulf, so seeing off Lakmal and Prasad in Colombo, statistically one of cricket history's least penetrating new-ball attacks (their career figures suggesting they offered the incision of an ice scalpel in a sub-Saharan operating theatre), will not have honed England ideally for the South African pace and swing barrage. As preparation for that task, it was about as appropriate as Neil Armstrong training for his rocket trip to the moon by hanging a cantaloupe melon from his bedroom ceiling, saying "5-4-3-2-1-blast-off" and throwing a dart at it.

Luckily, Strauss and his men have time and the West Indies series in which to reactivate their facing-swing-bowling heads. And hope that they work better than they did in 2010. And that England's bowlers continue to provide the grip and penetration of a Viagra-addled boa constrictor, as they have done consistently for the last two years.

Published on April 09, 2012 20:46

April 7, 2012

Multistat: 94

When in the 90s, hug your partner tight to calm yourself. Then proceed to your century

© AFP

The number of times Kevin Pietersen had batted in a Test since he last hit two sixes in an innings. He did so in both knocks in Colombo ‒ six in his winter-saving first-innings masterpiece, two more in a match-closing second-innings frolic – but had not cleared the ropes twice in an innings since his Leeds double-hundred against West Indies in May 2007.

Pietersen began his Test career in a blaze of badger-haired brazen-batted boundary-clearing thwacks. He hit two sixes in three of his first four Test innings, then seven in his Ashes-clinching symphony of strokeplay, and two or more in nine of his first 34 innings and 18 Tests (up to end of the 2006 Test summer). Since then, he had planked two maximums only in that Headingley demolition of West Indies five years ago – once in 107 innings over 64 Tests.

After a Test winter of unbroken personal and team failure, one of cricket's most intriguing players gloriously rediscovered his daring youthful brilliance. In Colombo, his second-innings 42 not out was his fastest score of more than 40 in Tests, and his 151 his second-fastest 100-plus score. From the platform laid by Strauss, Cook and Trott's disciplined grind, Pietersen annihilated a flagging and severely limited attack with calculated aggression of the highest calibre.

Also: The ideal age for Test batsmen against the current England team. Theoretically. Since July 2010, top-seven batsmen aged 33 and over have collectively averaged 39.1 against England, scoring 11 hundreds in 106 innings, whilst top-seven batsmen aged 32 and under have averaged 23.9, with just two centuries in 177 innings.

The average age of centurions against England in that time has been 34 years and eight months, and only Azhar Ali (excitedly looking forward to his 27th birthday when he hit 157 in Dubai) and Prasanna Jayawardene (31-and-a-half) have been under 33. I do not know if much (or indeed anything) can be read into this, but experience and know-how has certainly helped Dravid, Hussey and Mahela thrive despite England's unrelenting bowling pressure. (By comparison, against all other teams in the same period, 33-and-over-year-olds have averaged 43, and 32-and-unders have averaged 37.) Conclusion: When playing England, the older, the better. Ninety-four-year-old batsmen would smash Anderson and Swann all over the shop. There is no substitute for experience. And you do not get much more experienced than being 94 years old. Over 94, snoozing and forgetfulness might start to adversely affect batting success. The West Indian and South African selectors should take note before this summer's tours.

Published on April 07, 2012 22:00

April 2, 2012

A winter of discontent

Jonathan Trott: the sort who'd ask Luck home but send her off without a cup of tea

© AFP

England have one final chance to rescue some dignity from their unexpectedly disastrous Test winter. More specifically, England's batsmen have one final opportunity to issue an official, long-overdue and suitably grovelling apology to England's bowlers, in the form of a last-ditch outbreak of subcontinental competence. If any of England's willow-wielders does manage to add to Trott's solitary 2011-12 century, I hope he has the decency to hold up his bat to the bowlers in the Colombo pavilion to reveal an "I am so, so sorry" sticker plastered on the back, before flagellating himself in penance with a section of the boundary rope the England have found so elusive of late.

Seldom have two parts of the same cricket team performed at such extremes of proficiency. England's bowling has been almost uniformly excellent. The batting has been historically poor. It has been a little reminiscent of the ill-fated mixed-doubles tennis partnership between Martina Navratilova and Henry Kissinger, or the RSC's controversial 1960s production of Romeo and Juliet in which Hollywood heart-throb Paul Newman was cast opposite Chi Chi, the London Zoo panda. The difference is that Kissinger was never a truly world-class tennis player, and Chi Chi was more suited to comedic cameos than leading lady roles. Whereas England's batting, just a few months ago, was smashing records as if they were plates at the wedding of two Greek discus throwers.

England's bowlers enter their final Test of the 2011-12 season with a collective average of 26 this winter. Thus far, it has statistically been England's second best bowling winter since 1978-79, when Mrs Thatcher was still a slightly unsettling twinkle in the British electorate's eye, and Botham, Willis, Miller and others took advantage of a Packer-stripped Australia.

Since then, only in the 1996-97 season have England's bowlers returned a (fractionally) better average, and then their opponents were Zimbabwe and New Zealand, the two lowest-ranked Test nations at the time. Even in the 2000-01 winter, when England achieved outstanding series victories in both Pakistan and Sri Lanka, they averaged 33 with the ball.

For years, England had struggled to dismiss their opponents away from home, but they have now bowled their opposition out in both innings in nine of their last 11 away Tests. They had done so just five times in their previous 27 Tests outside England, dating back to their post-2005-Ashes comedown series in Pakistan, and in just 29% of their overseas Tests over the previous three decades.

England's bowlers (who in Galle became just the third attack in Test history to be on the losing side despite dismissing the opposition's top three for a total of less than 20 in both innings) have done their job all winter, a message conveyed unmistakeably by Jimmy Anderson's face when he trudged out to bat at 157 for 8, three hours after flogging a five-for out of the docile Galle surface.

England paid dearly for Monty's drops and Broad's no-ball (and, of course, for Jayawardene's refound mastery and Herath's crafty insistence), but the game was decided in their first innings, when they lost their top six wickets for less than 100 for the fifth time in four Tests this winter. They had been six down for under 100 just nine times in their previous 70 away Tests.

Published on April 02, 2012 22:32

Andy Zaltzman's Blog

- Andy Zaltzman's profile

- 12 followers

Andy Zaltzman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.