Andy Zaltzman's Blog, page 7

March 28, 2012

The moon-landing milestone

Andy Zaltzman looks up Tendulkar's stellar stats, wonders where Vernon Philander was lurking all these years, serves up tasty Mahela stats on a croissant, and answers your questions on music, blogging, rules of cricket, and more.

Download the podcast here (mp3, 14.9MB, right-click to save).

Download the podcast here (mp3, 14.9MB, right-click to save).

Published on March 28, 2012 22:51

March 22, 2012

The blog you've all been waiting for

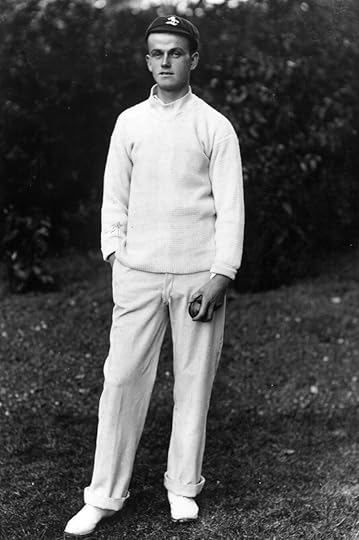

With the light so glorious for photography and not so much for cricket, Blythe posed when he was supposed to pick up and throw

© Getty Images

Another hectic week in international cricket, albeit one that, I can report first-hand, received little traction in the New York media. Sachin Tendulkar's 100th international hundred was passed over in favour of the altogether less-edifying spectacle of the principal Republican presidential candidates continuing to tear into each other like two lions dressed in zebra costumes, and the frankly alarming sight of the incumbent president of the world's top-ranked superpower taking a half-hour break from his no-doubt extremely hectic schedule to predict how the end of the student basketball season would pan out. Were there not more pressing issues for Mr Obama to address – the Syrian crisis, perhaps, or the continuing global economic blooper fest, or the likelihood of any cricketer scoring a century of international centuries, or England's prospects in overcoming their frailty against spin in their two-Test micro-tour of Sri Lanka? Evidently not.

I have now returned from the Big Apple to cricketing civilisation, slightly relieved, having seen how seriously they take their national sports - that the Americans plumped for baseball rather than cricket as their clouting-a-small-hard-ball-with-a-bit-of-wood sport of choice. If they had taken cricket to their ample sporting bosom when they had the chance (and let us not forget that the USA featured in the first ever international cricket match, against Canada in 1844), then the rest of the cricketing world might as well have taken its stumps home to make an ornamental plant stand. Major League Cricket would have made the IPL look like a home-made jam raffle at a village fete.

More on Tendulkar, Bangladesh, Vernon Philander – he of the Dickensian name and the appropriately 19th-century bowling average ‒ and the latest twists in this fascinating 2011-12 international season, in the new World Cricket Podcast later this week, but now it is time for Part 3 of The Official Confectionery Stall Going Out In A Blaze Of Glory Test XI – The Bowlers. Strap in.

Published on March 22, 2012 06:57

March 12, 2012

The Blaze of Glory XI - part two

Insurance companies that had to pay out huge sums to batsmen injured by the West Indies quartet have been hunting for this man for years now. Any info will be appreciated

© Getty Images

Greetings from New York City, where non-cricketous work has taken me temporarily to the place where Donald Bradman met Babe Ruth, and, one hopes, tried to convince the legendary Yankees slugger that if he did not hit the ball in the air so often, his innings might last rather longer. In fact, it is entirely possible that Donald Bradman ate a bagel, or put on a gorilla suit and tried to climb up the outside of the Empire State Building, or said "You talkin' to me?" whilst looking at himself in a mirror, within a just few blocks of where I am writing this now. I can feel the cricketing history in the air.

It is also possible that, given that he was in New York during a honeymoon which consisted of a four-month cricket tour, that the new Mrs Bradman at some point, perhaps on the sidewalk right below my window, pulled the Don aside and said: "Next time you go on a honeymoon, can I suggest you do so without 12 other men in tow? It is just not the more romantic way to make a girl feel special. And stop looking at the Statue Of Liberty like that. I know she's hot, but I AM YOUR WIFE. How was the game, darling?"

Welcome to Part 2 of the the Official Confectionery Stall Going Out In A Blaze Of Glory Test XI. Since Part 1 was released, Rahul Dravid has retired from international cricket. Had he had done so after last summer's series in England, he would have strolled into this team, despite India's total failure as a team, after one of the finest sustained displays of the craft of batsmanship seen in recent years.

Instead, a largely fruitless tour of Australia, and another sadly thorough walloping for his country, means that he has departed the Test scene with the same number of runs in his final Test as mustered batting legends RP de Groen and Franklyn Rose, and by joining Richard Blakey and Adrian Griffith as players who have exited Test cricket as part of a whitewashed team (plus, in fairness, several players of elevated cricketing stature) (and, potentially, the entire current England XI if they all decide to quit cricket and join a religious commune). It was an exit ill-befitting one of the Test game's finest players, after 16 years of silk and steel in his nation's cause, the undisputed Michelangelo Of The Forward Defensive.

Published on March 12, 2012 22:45

March 5, 2012

The Blaze of Glory XI

Andy Sandham: would have been a goner if they had Twitter in his time

© ESPNcricinfo Ltd

Further to my reflections on the dimming of great players' careers a couple of blogs ago, and the struggles of India's once-golden-but-now-greying batting generation, here, by way of happy contrast, is part one of the Official Confectionery Stall Going Out in a Blaze Of Glory Test XI.

The selection committee (me; my two children, who regrettably missed the selection meeting due to it being well past their bedtimes; and my wife, who abstained in protest at the increasingly domineering influence of Twenty20 on global cricket; and the ghost of former England skipper Douglas Jardine [via ouija board]) established various criteria for this deeply prestigious XI:

● Players should have had Test careers that were not an unremitting blaze of glory. Murali left the Test scene by spinning Sri Lanka to victory on his home turf and taking his 800th wicket with his final ball. There have been few more spectacular partings from any scene since Laika the Soviet Cosmodog's last ever walkies saw her chasing her final stick in outer space. Warne and McGrath helped Australia to a cleansing, vengeance-assisted 5-0 Ashes clouting of England, and exited to universal baggy green worship. Bradman, despite his final-innings duck, averaged 105 in his 15 post-war Tests, and in his penultimate innings had smashed 173 not out to chase down a record 404 in less than a day to win the fourth Test. But these men knew little but glory for most of their careers. And, in fact, all four of those legends saw their Test averages worsen (relatively) in their final series. The panel wanted players whose career-ending triumphs came, if not totally unexpectedly, then certainly in contrast to their overall career performances.

● The players' careers should have been long enough for the blaze of parting glory to stand out from a more general smoulder of adequacy. Barry Richards came into and departed from Test cricket in a veritable conflagration of magnificence in just seven innings, the last a dazzling 126 to help seal a South African whitewash of Australia. In the same game, Mike Procter had match figures of 9 for 103, to finish with 26 wickets at 13 in his final series. But it was the final series of two, and the other one had been almost equally stellar. They have no place in this team.

● The committee resisted the temptation to pick Jason Gillespie as a specialist batsman. Double-centuries against Bangladesh do not count as blazes of glory, any more than me slotting an ice-cool penalty past my three-year-old son in the Zaltzgarden last weekend warranted the celebration that it prompted.

● The committee, under the terms of the UN Convention on Sporting Selection Committees, reserved the right to select players on an unexplained personal whim.

Here are the top four batsmen:

1. Andrew Sandham (England, blazed out gloriously in 1929-30)

Sandham had failed as a Test batsman in the early 1920s, with a solitary half-century in ten sporadic Tests, but, aged 39, with England's resources stretched, he was selected for the tour of West Indies in 1929-30. It was an under-strength team. Not only did Hobbs, Sutcliffe and Hammond all take the winter off, but England were simultaneously playing another Test series in New Zealand. And to think that people complain about the hectic international schedule and player rotation devaluing international caps now.

Surrey stalwart Sandham scored 152 and 51 in the first Test, but followed up with four single-figure scores in the next two, and thanked his lucky stars that technology's development of the internet message board remained a solid 70 or so years in the future, and that 1930 cricket fans would merely tut quietly at their newspapers in a few days' time, whilst smoking a pipe, rather than instantly logging on, impugning Sandham's parentage, and calling for Lancashire's Frank Watson to be given a go instead, after a promising season in the County Championship.

Sandham walked to the crease in the final Test with a Test average of 24 after 13 Tests. He walked away from it at the end of the match with a rather broader grin, and an average of 38, after scoring 325 and 50. His efforts did not result in a valedictory victory, however. The supposedly timeless game was called off as a draw to enable England to catch the boat home.

Arguably, with a handy first-innings lead of 563, captain Freddie Calthorpe could have risked enforcing the follow-on, but erred on side of caution, to the surprise of many, not least of caution itself, which in the circumstances was settling down for a spot of sunbathing and not expecting to be disturbed. Rain, the transatlantic shipping schedule, and the genius of George Headley saved West Indies, and with Hobbs and Sutcliffe restored for the summer's Ashes, Sandham never played Test cricket again.

(Footnote: Sandham was born in Streatham, where I now live, so, according to the traditions of selectorial privilege applied intermittently throughout cricket history, I'm picking him.)

Published on March 05, 2012 21:33

February 27, 2012

Thirteen problems

If the tattoo sleeve doesn't scare batsmen, some gentle ribbing will

© Getty Images

I promised in the last Confectionery Stall to share some of the cricket-related questions that have been occupying me of late. Arguably, there have been too many cricket-related questions occupying me of late (and by "of late", I mean "since the age of six"), but if they perform the useful function of helping me not think about, for example, the state of the global economy, the international response to the Syrian crisis, how my parenting skills are likely to fare when my children are teenagers, or the future of Test matches, then so be it.

Here they are. Write your answers on a piece of parchment, and bury them in your garden to confuse future archaeologists.

● Kevin Pietersen's ODI hundreds are like London buses – you wait three years and three months for one, and then two turn up in the space of four days. (I admit that I did the empirical research for this joke years ago, waiting at a bus stop in La Paz, Bolivia.) (And that the two that eventually turned up were in fact not London buses, but my parents asking me to come back home.) (But the point stands.) Why the delay? (a) essential maintenance work; (b) Pietersen had been batting in the wrong position, at 3 or 4, for too long – most of his best ODI innings have now been played either early in his career at 5 or 6, coming to the wicket when his run-scoring task was quite clear, or, more recently, opening, when he can shape England's innings from the start; (c) Fate; (d) rogue planetary alignments; (e) Pietersen wanted to disprove the fears expressed when he was appointed England skipper that the captaincy would affect his batting, by not scoring an ODI hundred for three years and two months after having the captaincy taken from him; (f) a combination of luck, form, injury, technical glitches and the opposition insisting on getting him out; or (g) I don't know.

● Why does a team lose a DRS referral when the replay returns an "Umpire's Call" verdict, proving that the referring team was either essentially right, or only infinitesimally wrong, to refer it, but either not quite right enough to overturn the decision, or wrong by a sufficiently small margin as to raise the very real possibility that the ball shown to be shaving the stump by a millimetre might not have actually knocked the bail off? Does this not penalise them twice?

● And, whilst we are on the subject of the DRS, why do teams only receive one referral in an ODI innings, despite the fact that they are allowed to lose the same number of wickets as in a Test innings? Does this suggest that the entire system, far from aiming to eliminate umpiring "howlers", is in fact designed simply to make them even more annoying?

● Was Dr Faustus employed by the BCCI as part of their secret How To Win The World Cup panel? If so, does India now regret having implemented the naughty Doctor's plan to trade World Cup glory for Test meltdown?

● If Jade Dernbach bowls more than 50% of his deliveries as slower balls, will he be officially be reclassified as a spinner? Albeit a spinner with a useful much-quicker ball?

● Is the success of Dernbach's seemingly unfathomable and recently match-winning slower ball due to the fact that, when his heavily-inked arm rotates at the required velocity to deliver it, an optical illusion is created whereby the tattoos blend to create an animation of WG Grace biting the head off a squirrel, thus distracting the batsman?

● Given that Saeed Ajmal took 39 wickets at an average of 15.9 in the Tests, ODIs and T20s against England, and that amidst that run of scheming tweak wizardry, he took 0 for 32 in an ODI against Afghanistan, should England be sending their players to spend a year in Afghanistan to work on their techniques against mystery spin?

● Does Eoin Morgan realise that a batsman having a pronounced duck amongst his trigger movements could be risking bad karma?

● When, why and how did Shahid Afridi persuade himself that he couldn't bat properly anymore, despite considerable evidence to the contrary? He was praised for his "maturity" in scoring a fine half-century in the third ODI – when he was an immature, hot-headed 18-year-old, he scored an ultimately match-winning five-hour 141 when opening the batting in a low-scoring Test match in Chennai. If only Pakistan had selected him at the age of six, he could have been one of the most immovable grinders of the modern age.

● What does Azhar Ali ‒ of whom this column is an unashamed admirer as a Test player but who had only played four List A one-day matches anywhere in the world in the

22 months before his recall to the green pyjamas ‒ think when he goes out to bat in a one-day international? Is it the same as what prominent miserablist songsmith Leonard Cohen would think if forced to take part in a World Heavyweight title fight, i.e.: "I am good at what I do, but I am seriously out of my comfort zone"?

● How good will Steven Finn prove to be? In the recent ODI series, he has looked as if he could become one of England's best since Freddie Trueman. If he can get into the Test side. And not get injured. And keep bowling at an out-of-form Mohammad Hafeez. His 13 wickets for 134 runs (at an average of 10.3, the best by an England bowler with 10 or more wickets in an ODI series or tournament), mean that he has taken 20 wickets at 16, with an economy rate of 3.8, in his last seven ODIs. In his first eight ODIs, he took eight wickets at 50 and went for 5.5 per over. In his 12 Tests to date, he has 50 wickets at 26.9. If he can directly replicate his proportional ODI improvement in the Test arena, then, in his next 10½ Tests, he will take 125 wickets at 8.6. That will not happen, but, if it does, which it won't, it will be worth watching. As will fast bowling in general in the next few years, if the last six months have not been an elaborate hoax.

● Ravi Bopara scored two half-centuries in two innings in the ODI series, but could, and probably should, have been out for 1 three times in those two innings, reprieved by a missed stumping, a botched lbw decision and a blooped run-out. So, for any philosophers out there, was Bopara batting well or badly?

● Why is it so hard to find decent statues of umpire Daryl Harper these days? My garden feels empty without one.

Published on February 27, 2012 22:18

February 20, 2012

The problem with Tendulkar

Is the ghost of Don Bradman interfering in his quest for the 100th?

©Getty Images

Amongst all the cricket-related questions that fire themselves into my brain during quiet moments, of which there are disturbingly many for a supposedly grown-up father of two and alleged political satirist, the one that has put its hand up and asked itself most frequently of late has been: How can you tell when a cricketer is in terminal career decline? (I will share some of the other questions in another blog later in the week.)

There is no formula for judging when a blip in form becomes the harbinger of inevitable retirement, or when those proposing the adage "form is temporary, class is permanent", start to add the words "but Father Time can be a cantankerous old bastard when he wants to be".

It will not have escaped the notice of the more eagle-eyed cricket followers that Sachin Tendulkar, the cricketing icon of his age and one of the greatest players in the history of the game, is still awaiting his 100th international hundred. All seven billion people currently at large in the world have not scored 100 international hundreds, and for the moment Tendulkar is still one of the them. All their forebears also failed to reach that milestone, and given the changing schedule and nature of modern cricket, it seems likely that all their descendants will fail to reach it as well.

So it is perhaps understandable that, in a game obsessed with milestones, this megamilestone is causing rather more fretting than, objectively, it should. Reaching it is not going to make Tendulkar a greater player, and failing to reach it would not make him a lesser one - though it would be quite annoying for him, and for cricket. If Neil Armstrong had landed his magic rocket on the moon, taken one look outside, decided it looked a bit chilly for a walk, and blasted himself and his buddies straight back to Earth, it would still have been a hugely impressive voyage. Having journeyed so far, obviously the symbolic moment of placing the flag on the moon was important – but the overall achievements of the space programme, and the broader technological miracle of being able to fire people 250,000 miles in a souped-up tin can and get them home again afterwards were, ultimately, of more significance.

It is now 29 innings since Tendulkar scored his 99th international hundred. It is his second longest sequence of innings without a century in his unfathomably massive international career (there was a 34-innings hiatus between hundred No. 78 and hundred No. 79, in 2007).

It is worth thinking back to that 99th hundred, his second century of a triumphant World Cup, both of them innings of peerless brilliance, in which his technique, judgement and boldness were close to flawless; a master in total control of his craft. At that point he had scored 11 hundreds for India in 14 months, at a rate of one every three innings, including eight in 15 Tests, and the first-ever ODI double-century. Statistically he had never been as good.

Since then, there have been 11 months and 29 innings of finely crafted near-misses, sawn-off cameos and failures, a cocktail of uncompleted brilliance and uncharacteristic uncertainty.

Why?

Has the pressure of reaching a milestone, to which no other player has ever, or is ever likely to, come close, affected the mind of the master? Have his 38 years and ten months on the planet, and more particularly his 22 years and three months of international cricket, finally caught up with him? Has his luck simply changed? Is he tired? Is he bored of watching a small, hard, red round thing fly towards him whilst hundreds of millions of people watch to see if he can hit it with a plank of wood? When you have done so 50,000 times, the novelty must wear off. Is he simply sated of milestones, after snaring his 200th international wicket in the Cape Town Test just over a year ago (for which, incidentally, there had been a 34-match, 15-month wait after wicket No. 199)? Or has the ghost of Donald Bradman been interfering, trying to ensure that his closest modern equivalent ends up like him, stranded on 99?

Published on February 20, 2012 23:10

February 15, 2012

The ugliest thing in cricket

Andy Zaltzman and Daniel Norcross talk about Pakistan's abject and deceitful performance in the UAE, Saeed Ajmal's beautiful hair, how World War Two ruined batting techniques, and which animal will make the best wicketkeeper

Download the podcast here (mp3, 29MB, right-click to save).

Download the podcast here (mp3, 29MB, right-click to save).

Published on February 15, 2012 21:07

February 9, 2012

Whacked in the face with a live barracuda at 3.30am

"What do you mean, no backbone?"

© Getty Images

A few quick thoughts and numbers arising from the Pakistan v England series (I will do a full review of it in next week's World Cricket Podcast). Some people are outlandishly claiming that the series ended in a 3-0 whitewash of the Universe's Number One-Ranked Cricket Machine by a side that recently was not merely plumbing depths of on-pitch ineptitude and off-pitch naughtiness, but was fitting a basin, bath and power shower in those depths. This story is so far-fetched that it must be discounted. It cannot have happened. It cannot have happened. It simply cannot have happened. I checked the rankings this morning. England are still the Universe's Number One-Ranked Cricket Machine. It must have been a hoax.

Nevertheless, until the hoax is conclusively proved and accepted by the ICC, we must reflect on what allegedly happened. And what allegedly happened was one of the most extraordinary collective batting failures in cricket history, and one of the finest series wins of recent decades. England averaged below 20 runs per wicket for only the second time since Archduke Franz Ferdinand had his clogs controversially and unhelpfully popped, and registered their lowest team series runs-per-wicket figure since shortly after Tchaikovsky premiered his smash-hit ballet Sleeping Beauty, and shortly before the birth of professional French President and eight-time European Nose Of The Year winner Charles de Gaulle (in 1890 – thank you, Wikipedia).

England's numbers 4, 5 and 6 (Pietersen, Bell and Morgan, with one innings at 6 by Prior) averaged 11.94, a figure that, since the First World War, has only been out-ineptituded once in a three-Test series ‒ by a motley collection of Indians against New Zealand in 1969-70.

The people I feel most sorry for, with regard to this historic disintegration of England's stellar batting line-up, are the poor, unfortunate bat sponsors. For the last year they had got their money's worth. In their previous 13 Tests over three series, England bats had been waggled in celebration on 93 occasions – 54 times on reaching 50, 22 times to mark a century, ten times for 150, six times to celebrate double-centuries, and once by Alistair Cook to mark England's first 250 since Gooch clomped India all around Lord's in 1990. These had been unprecedented times for English bat-waggling. But in the three UAE Tests, those same bats remained eerily unwaggly.

Published on February 09, 2012 04:03

January 30, 2012

Pietersen's compelling mastery and idiocy

Saeed Ajmal does a double-take when he hears Ian Bell cussing in Afrikaans

© Getty Images

The English media have never been especially adept at responding to national defeats with calm rationality. No sooner had King Harold picked up his career-ending eye injury at the Battle of Hastings than the critics were busy weaving tapestries slamming his technique against the moving arrow, whilst armchair minstrels were composing ballads suggesting that the young Earl Of Mercia should be given a chance to fight the Normans, even if his form on the county battle circuit had been none too impressive and he had recently been shown up by the Vikings as not quite ready for the top level.

The Ashes were born in 1882 when the media lambasted England for collapsing on a difficult pitch against top-class bowling in a low-scoring match. How times change. As the pressure mounted, Lucas and Lyttleton went into their shells, and, from 53 for 4, scored just 13 runs in 50 minutes. How times change. A wicket fell, and then the tail subsided in a quickfire flurry of wickets. How times change.

Losing skipper Albert "Monkey" Hornby must have thanked his lucky stars that the widespread use of social media remained 120 years in the future. The supporters would have tweeted their fury: "Hey @WGGrace, you're being picked on reputation. Shave the beard it looks cocky when you lose. #engvaus"… "Gutted. Fair play to Aus, @DemonSpofforth bowled great, but we were R-U-B-B-I-S-H"… "Oi Lucas you loser what u doing scoring 5 off 55 balls learn 2 hit the ball u overrated waste of space"… "Wats @ANHornby even in the team 4 let alone captin?! Hes totly usless!! A real monkey wud be beter #dropthehorn"… "ha ha england u not so good now r u wen ball swings we ausies got r veng 4 1880 ha ha go oz go. PS ulyett sucks big time"… "I ate my umbrella and now I feel sick. #greatgame".

I wrote in my last blog about how Andrew Strauss' England have lost rarely but spectacularly, and had always bounced back strongly in their next Test. , they managed both to bounce back strongly from their Dubai debacle, and to lose spectacularly anyway. A high-tariff manoeuvre, which they pulled off with rare aplomb. They played three-quarters of a very good match, and one-quarter of a statistics-meltingly terrible one. Pakistan's tweakers took advantage with surgical brilliance. The cricket was utterly gripping – less than two runs per over on the final day, with only nine boundaries, yet remorselessly exciting.

England, who had been in control throughout the game, without ever hatching that egg of control into a condor of dominance, were rapidly overturned, like a chef who has carefully chopped all his vegetables and followed his recipe, only to suddenly find himself inside a giant wok, being aggressively flambéd.

Published on January 30, 2012 22:35

January 24, 2012

Beaten like a naughty egg white

"Everyone contributed to that loss, and I'm proud of you all"

© Getty Images

England do not lose too many Test matches these days. But when they do lose, they lose properly. They go down hard, they go down fast, and they go down in a blaze of statistical ignominy. Since the Flower-Strauss era began, with an almost mathematics-defying innings defeat after collapsing to 51 all out in Jamaica three years ago, England have lost only five more Tests (which, to put their current travails in perspective, is as many as they lost in six weeks in Australia in 2006-07, or in two months against the West Indies whenever they played them in the mid-1980s). They have won 20, drawn 11, and risen to the top of the world rankings. But when they fail, they do not mess about with half-measures. They take a treble measure of neat cricketing vodka, and wash it down with a meths chaser.

The ten-wicket Dubai splattering by a resurgent, skilful and determined Pakistan followed in the pattern of the 267-run clouting in Perth in last winter's Ashes (do not let Australians persuade you that was in fact "last summer's Ashes", it was not; it was in the winter; after watching it, I went outside and had to put a woolly hat on; therefore it was winter; the Australians play cricket in winter; that is a fact). The sequence was partially interrupted by a fluctuating four-wicket loss to Pakistan at The Oval, a close game but one that nevertheless featured some historically inept batting by England. Prior to that, England had been clobbered by an innings by South Africa in Johannesburg, and by Australia at Headingley.

All of these defeats have featured collapses of 1929 stock market proportions - displays of landmark batting uselessness in an era notable for its unusually persistent and increasingly dominant successes, and also for its dogged, match-saving rearguards. The Jamaica debacle was England's third-lowest Test score of all time, and only the fifth time that ten Englishmen have failed to reach double figures in a Test innings; at Headingley, England had eight players dismissed for 3 or fewer in a Test innings for the first time in their history, registered 13 dismissals for less than five runs for the second time ever (the first was another 1880s scorebook-burning classic), and were dismissed in under 34 overs in an Ashes Test innings for the second time in 105 years; in Johannesburg, England failed to last 550 balls in their two innings combined for just the third time in over 100 years; at The Oval, all of England's top six were dismissed for 17 or fewer in the first innings of a Test for the first time since 1887, none of England's bottom six scored more than 6 runs in the second innings of a Test for only the seventh time in their history, and England lost their last seven wickets for less than 30 runs for the first time in over a decade; in Perth, they failed to last 100 overs in the two innings of a Test in Australia for the first time since 1903-04.

Dubai was the latest outbreak of proper, unmitigated batting failure. England slunk to 42 for 4 in the first innings and 35 for 4 in the second ‒ the fifth-worst match performance by England's top four wickets since the First World War. They then subsided to 94 for 7 and 87 for 7 – the first time since 1988 that England have lost their seventh wicket for less than 100 in both innings of a Test, and the sixth-worst match performance by England's top seven wickets since the treaty of Versailles heralded 21 years of glorious peace for the world. (Those 21 years, of course, followed four years of war – giving Versailles an 84% success rate, and thus making it a better treaty than Bradman was a batsman. Arguably.)

Published on January 24, 2012 19:26

Andy Zaltzman's Blog

- Andy Zaltzman's profile

- 12 followers

Andy Zaltzman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.