Jeremy Keith's Blog, page 94

November 15, 2015

Home screen

Remy posted a screenshot to Twitter last week.

That “Add To Home Screen” dialogue is not something that Remy explicitly requested (though, of course, you can���and should���choose to add adactio.com to your home screen). That prompt appears in Chrome on Android as the result of a fairly simple algorithm based on a few factors:

The website is served over HTTPS. My site is.

The website has a manifest file. Here’s my JSON manifest file.

The website has a Service Worker. Here’s my site’s Service Worker script (although a little birdie told me that the Service Worker script can be as basic as a blank file).

The user visits the website a few times over the course of a few days.

I think that’s a reasonable set of circumstances. I particularly like that there is no way of forcing the prompt to appear.

There are some carrots in there: Want to have the user prompted to add your site to their home screen? Well, then you need to be serving on a secure connection, and you’d better get on board that Service Worker train.

Speaking of which, after I published a walkthrough of my first Service Worker, I got an email bemoaning the lack of browser support:

I was very much interested myself in this topic, until I checked on the ���Can I use������ site the availability of this technology. In one word ���limited���. Neither Safari nor IOS Safari support it, at least now, so I cannot use it for implementing mobile applications.

I don’t think this is the right way to think about Service Workers. You don’t build your site on top of a Service Worker���you add a Service Worker on top of your existing site. It has been explicitly designed that way: you can’t make it the bedrock of your site’s functionality; you can only add it as an enhancement.

I think that’s really, really smart. It means that you can start implementing Service Workers today and as more and more browsers add support, your site will appear to get better and better. My site worked fine for fifteen years before I added a Service Worker, and on the day I added that Service Worker, it had no ill effect on non-supporting browsers.

Oh, and according to the Webkit five year plan, Service Worker support is on its way. This doesn’t surprise me. I can’t imagine that Apple would let Google upstage them for too long with that nice “add to home screen” flow.

Alas, Mobile Safari’s glacial update cycle means that the earliest we’ll see improvements like Service Workers will probably be September or October of next year. In the age of evergreen browsers, Apple’s feast-or-famine approach to releasing updates is practically indistinguishable from stagnation.

Still, slowly but surely, game-changing technologies are landing in browsers. At the same time, the long-term problems with betting on native apps are starting to become clearer. Native apps are still ahead of what can be accomplished on the web, but it was ever thus:

The web will always be lagging behind some other technology. I���m okay with that. If anything, I see these other technologies as the research and development arm of the web. CD-ROMs, Flash, and now native apps show us what authors want to be able to do on the web. Slowly but surely, those abilities start becoming available in web browsers.

The pace of this standardisation can seem infuriatingly slow. Sometimes it is too slow. But it���s important that we get it right���the web should hold itself to a higher standard. And so the web plays the tortoise while other technologies race ahead as the hare.

It’s interesting to see how the web could take the desirable features of native���offline support, smooth animations, an icon on the home screen���without sacrificing the strengths of the web���linking, responsiveness, the lack of App Store gatekeepers. That kind of future is what Alex is calling progressive apps:

Critically, these apps can deliver an even better user experience than traditional web apps. Because it���s also possible to build this performance in as progressive enhancement, the tangible improvements make it worth building this way regardless of ���appy��� intent.

Flipkart recently launched something along those lines, although it’s somewhat lacking in the “enhancement” department; the core content is delivered via JavaScript���a fragile approach.

What excites me is the prospect of building services that work just fine on low-powered devices with basic browsers, but that also take advantage of all the great possibilities offered by the latest browsers running on the newest devices. Backwards compatible and future friendly.

And if that sounds like a na��ve hope, then I humbly suggest that Service Workers are a textbook example of exactly that approach.

November 7, 2015

My first Service Worker

I’ve made no secret of the fact that I’m really excited about Service Workers. I’m not alone. At the Coldfront conference in Copenhagen, pretty much every talk mentioned Service Workers.

Obviously I’m excited about what Service Workers enable: offline caching, background processes, push notifications, and all sorts of other goodies that allow the web to compete with native. But more than that, I’m really excited about the way that the Service Worker spec has been designed. Instead of being an all-or-nothing technology that you have to bet the farm on, it has been deliberately crafted to be used as an enhancement on top of existing sites (oh, how I wish that web components would follow a similar path).

I’ve got plenty of ideas on how Service Workers could be used to enhance a community site like The Session or the kind of events sites that we produce at Clearleft, but to begin with, I figured it would make sense to use my own personal site as a playground.

To start with, I’ve already conquered the first hurdle: serving my site over HTTPS. Service Workers require a secure connection. But you can play around with running a Service Worker locally if you run a copy of your site on localhost.

That’s how I started experimenting with Service Workers: serving on localhost, and stopping and starting my local Apache server with apachectl stop and apachectl start on the command line.

That reminds of another interesting use case for Service Workers: it’s not just about the user’s network connection failing (say, going into a train tunnel); it’s also about your web server not always being available. Both scenarios are covered equally.

I would never have even attempted to start if it weren’t for the existing examples from people who have been generous enough to share their work:

The Guardian Developer Blog documents how they provide an offline page.

Nicolas documented how he set up a Service Worker for his site.

Jake put together an offline cookbook covering the many ways that Service Workers can be used.

Also, I knew that Jake was coming to FF Conf so if I got stumped, I could pester him. That’s exactly what ended up happening (thanks, Jake!).

So if you decide to play around with Service Workers, please, please share your experience.

It’s entirely up to you how you use Service Workers. I figured for a personal site like this, it would be nice to:

Explicitly cache resources like CSS, JavaScript, and some images.

Cache the homepage so it can be displayed even when the network connection fails.

For other pages, have a fallback “offline” page to display when the network connection fails.

So now I’ve got a Service Worker up and running on adactio.com. It will only work in Chrome, Android, Opera, and the forthcoming version of Firefox …and that’s just fine. It’s an enhancement. As more and more browsers start supporting it, this Service Worker will become more and more useful.

How very future friendly!

The code

If you’re interested in the nitty-gritty of what my Service Worker is doing, read on. If, on the other hand, code is not your bag, now would be a good time to bow out.

If you want to jump straight to the finished code, here’s a gist. Feel free to take it, break it, copy it, improve it, or do anything else you want with it.

To start with, let’s establish exactly what a Service Worker is. I like this definition by Matt Gaunt:

A service worker is a script that is run by your browser in the background, separate from a web page, opening the door to features which don’t need a web page or user interaction.

register

From inside my site’s global JavaScript file���or I could do this from a script element inside my pages���I’m going to do a quick bit of feature detection for Service Workers. If the browser supports it, then I’m going register my Service Worker by pointing to another JavaScript file, which sits at the root of my site:

if (navigator.serviceWorker) {

navigator.serviceWorker.register('/serviceworker.js', {

scope: '/'

});

}

The serviceworker.js file sits in the root of my site so that it can act on any requests to my domain. If I put it somewhere like /js/serviceworker.js, then it would only be able to act on requests to the /js directory.

Once that file has been loaded, the installation of the Service Worker can begin. That means the script will be installed in the user’s browser ���and it will live there even after the user has left my website.

install

I’m making the installation of the Service Worker dependent on a function called updateStaticCache that will populate a cache with the files I want to store:

self.addEventListener('install', function (event) {

event.waitUntil(updateStaticCache());

});

That updateStaticCache function will be used for storing items in a cache. I’m going to make sure that the cache has a version number in its name, exactly as described in the Guardian’s use case. That way, when I want to update the cache, I only need to update the version number.

var staticCacheName = 'static';

var version = 'v1::';

Here’s the updateStaticCache function that puts the items I want into the cache. I’m storing my JavaScript, my CSS, some images referenced in the CSS, the home page of my site, and a page for displaying when offline.

function updateStaticCache() {

return caches.open(version + staticCacheName)

.then(function (cache) {

return cache.addAll([

'/path/to/javascript.js',

'/path/to/stylesheet.css',

'/path/to/someimage.png',

'/path/to/someotherimage.png',

'/',

'/offline'

]);

});

};

Because those items are part of the return statement for the Promise created by caches.open, the Service Worker won’t install until all of those items are in the cache. So you might want to keep them to a minimum.

You can still put other items in the cache, and not make them part of the return statement. That way, they’ll get added to the cache in their own good time, and the installation of the Service Worker won’t be delayed:

function updateStaticCache() {

return caches.open(version + staticCacheName)

.then(function (cache) {

cache.addAll([

'/path/to/somefile',

'/path/to/someotherfile'

]);

return cache.addAll([

'/path/to/javascript.js',

'/path/to/stylesheet.css',

'/path/to/someimage.png',

'/path/to/someotherimage.png',

'/',

'/offline'

]);

});

}

Another option is to use completely different caches, but I’ve decided to just use one cache for now.

activate

When the activate event fires, it’s a good opportunity to clean up any caches that are out of date (by looking for anything that doesn’t match the current version number). I copied this straight from Nicolas’s code:

self.addEventListener('activate', function (event) {

event.waitUntil(

caches.keys()

.then(function (keys) {

return Promise.all(keys

.filter(function (key) {

return key.indexOf(version) !== 0;

})

.map(function (key) {

return caches.delete(key);

})

);

})

);

});

fetch

The fetch event is fired every time the browser is going to request a file from my site. The magic of Service Worker is that I can intercept that request before it happens and decide what to do with it:

self.addEventListener('fetch', function (event) {

var request = event.request;

...

});

POST requests

For a start, I’m going to just back off from any requests that aren’t GET requests:

if (request.method !== 'GET') {

event.respondWith(

fetch(request, { credentials: 'include' })

);

return;

}

That’s basically just replicating what the browser would do anyway. But even here I could decide to fall back to my offline page if the request doesn’t succeed. I do that using a catch clause appended to the fetch statement:

if (request.method !== 'GET') {

event.respondWith(

fetch(request, { credentials: 'include' })

.catch(function () {

return caches.match('/offline');

})

);

return;

}

HTML requests

I’m going to treat requests for pages differently to requests for files. If the browser is requesting a page, then here’s the order I want:

Try fetching the page from the network first.

If that doesn’t work, try looking for the page in the cache.

If all else fails, show the offline page.

First of all, I need to test to see if the request is for an HTML document. I’m doing this by sniffing the Accept headers, which probably isn’t the safest method:

if (request.headers.get('Accept').indexOf('text/html') !== -1) {

Now I try to fetch the page from the network:

event.respondWith(

fetch(request, { credentials: 'include' })

);

If the network is working fine, this will return the response from the site and I’ll pass that along.

But if that doesn’t work, I’m going to look for a match in the cache. Time for a catch clause:

.catch(function () {

return caches.match(request);

})

So now the whole event.respondWith statement looks like this:

event.respondWith(

fetch(request, { credentials: 'include' })

.catch(function () {

return caches.match(request)

})

);

Finally, I need to take care of the situation when the page can’t be fetched from the network and it can’t be found in the cache.

Now, I first tried to do this by adding a catch clause to the caches.match statement, like this:

return caches.match(request)

.catch(function () {

return caches.match('/offline');

})

That didn’t work and for the life of me, I couldn’t figure out why. Then Jake set me straight. It turns out that caches.match will always return a response …even if that response is undefined. So a catch clause will never be triggered. Instead I need to return the offline page if the response from the cache is falsey:

return caches.match(request)

.then(function (response) {

return response || caches.match('/offline');

})

With that cleared up, my code for handing HTML requests looks like this:

event.respondWith(

fetch(request, { credentials: 'include' })

.catch(function () {

return caches.match(request)

.then(function (response) {

return response || caches.match('/offline');

})

})

);

Actually, there’s one more thing I’m doing with HTML requests. If the network request succeeds, I stash the response in the cache.

Well, that’s not exactly true. I stash a copy of the response in the cache. That’s because you’re only allowed to read the value of a response once. So if I want to do anything with it, I have to clone it:

var copy = response.clone();

caches.open(version + staticCacheName)

.then(function (cache) {

cache.put(request, copy);

});

I do that right before returning the actual response. Here’s how it fits together:

if (request.headers.get('Accept').indexOf('text/html') !== -1) {

event.respondWith(

fetch(request, { credentials: 'include' })

.then(function (response) {

var copy = response.clone();

caches.open(version + staticCacheName)

.then(function (cache) {

cache.put(request, copy);

});

return response;

})

.catch(function () {

return caches.match(request)

.then(function (response) {

return response || caches.match('/offline');

})

})

);

return;

}

Okay. So that’s requests for pages taken care of.

File requests

I want to handle requests for files differently to requests for pages. Here’s my list of priorities:

Look for the file in the cache first.

If that doesn’t work, make a network request.

If all else fails, and it’s a request for an image, show a placeholder.

Step one: try getting the file from the cache:

event.respondWith(

caches.match(request)

);

Step two: if that didn’t work, go out to the network. Now remember, I can’t use a catch clause here, because caches.match will always return something: either a response or undefined. So here’s what I do:

event.respondWith(

caches.match(request)

.then(function (response) {

return response || fetch(request);

})

);

Now that I’m back to dealing with a fetch statement, I can use a catch clause to take care of the third and final step: if the network request doesn’t succeed, check to see if the request was for an image, and if so, display a placeholder:

.catch(function () {

if (request.headers.get('Accept').indexOf('image') !== -1) {

return new Response('...', { headers: { 'Content-Type': 'image/svg+xml' }});

}

})

I could point to a placeholder image in the cache, but I’ve decided to send an SVG on the fly using a new Response object.

Here’s how the whole thing looks:

event.respondWith(

caches.match(request)

.then(function (response) {

return response || fetch(request)

.catch(function () {

if (request.headers.get('Accept').indexOf('image') !== -1) {

return new Response('...', { headers: { 'Content-Type': 'image/svg+xml' }});

}

})

})

);

The overall shape of my code to handle fetch events now looks like this:

self.addEventListener('fetch', function (event) {

var request = event.request;

// Non-GET requests

if (request.method !== 'GET') {

event.respondWith(

...

);

return;

}

// HTML requests

if (request.headers.get('Accept').indexOf('text/html') !== -1) {

event.respondWith(

...

);

return;

}

// Non-HTML requests

event.respondWith(

...

);

});

Feel free to peruse the code.

Next steps

The code I’m running now is fine for a first stab, but there’s room for improvement.

Right now I’m stashing any HTML pages the user visits into the cache. I don’t think that will get out of control���I imagine most people only ever visit just a handful of pages on my site. But there’s the chance that the cache could get quite bloated. Ideally I’d have some way of keeping the cache nice and lean.

I was thinking: maybe I should have a separate cache for HTML pages, and limit the number in that cache to, say, 20 or 30 items. Every time I push something new into that cache, I could pop the oldest item out.

I could imagine doing something similar for images: keeping a cache of just the most recent 10 or 20.

If you fancy having a go at coding that up, let me know.

Lessons learned

There were a few gotchas along the way. I already mentioned the fact that caches.match will always return something so you can’t use catch clauses to handle situations where a file isn’t found in the cache.

Something else worth noting is that this:

fetch(request);

…is functionally equivalent to this:

fetch(request)

.then(function (response) {

return response;

});

That’s probably obvious but it took me a while to realise. Likewise:

caches.match(request);

…is the same as:

caches.match(request)

.then(function (response) {

return response;

});

Here’s another thing… you’ll notice that sometimes I’ve used:

fetch(request);

…but sometimes I’ve used:

fetch(request, { credentials: 'include' } );

That’s because, by default, a fetch request doesn’t include cookies. That’s fine if the request is for a static file, but if it’s for a potentially-dynamic HTML page, you probably want to make sure that the Service Worker request is no different from a regular browser request. You can do that by passing through that second (optional) argument.

But probably the trickiest thing is getting your head around the idea of Promises. Writing JavaScript is generally a fairly procedural affair, but once you start dealing with then clauses, you have to come to grips with the fact that the contents of those clauses will return asynchronously. So statements written after the then clause will probably execute before the code inside the clause. It’s kind of hard to explain, but if you find problems with your Service Worker code, check to see if that’s the cause.

And remember, please share your code and your gotchas: it’s early days for Service Workers so every implementation counts.

Updates

I got some very useful feedback from Jake after I published this…

Expires headers

By default, JavaScript files on my server are cached for a month. But a Service Worker script probably shouldn’t be cached at all (or cached for a very, very short time). I’ve updated my .htaccess rules accordingly:

ExpiresDefault "now"

Credentials

If a request is initiated by the browser, I don’t need to say:

fetch(request, { credentials: 'include' } );

It’s enough to just say:

fetch(request);

Scope

I set the scope parameter of my Service Worker to be “/” …but because the Service Worker is sitting in the root directory anyway, I don’t really need to do that. I could just register it with:

if (navigator.serviceWorker) {

navigator.serviceWorker.register('/serviceworker.js');

}

If, on the other hand, the Service Worker file were sitting in a folder, but I wanted it to act on the whole site, then I would need to specify the scope:

if (navigator.serviceWorker) {

navigator.serviceWorker.register('/path/to/serviceworker.js', {

scope: '/'

});

}

November 2, 2015

Fortune

A few months back, I got an email with the subject line:

interview request (Fortune magazine - U.S.)

“Ooh, sounds interesting”, I thought. I read on���

I’ve been tasked with writing a profile of you from my tech editor at Fortune, a business magazine in the U.S.

I’m headed to Brighton this weekend and hoping we can meet up. Can you call me at +X XXX XXX XXX as soon as you can? Thanks. I’ll try you on your mobile in a few minutes.

Sounded urgent! “I’d better call him straight away”, I thought. So I did just that. It went to voicemail. The voicemail inbox was full. I couldn’t leave a message.

So I sent him an email and eventually we managed to have a phone conversation together. Richard���for that is his name���told me about the article he wanted to write about the “scene” in Brighton. He asked if there was anyone else I thought he should speak to. I was more than happy to put him in touch with Rosa and Dot, Jacqueline, Jonathan, and other lovely people behind Brighton institutions like Codebar, Curiosity Hub, and The Skiff. We also arranged to meet up when he came to town.

The day of Richard’s visit rolled around and I spent the afternoon showing him around town and chatting. He seemed somewhat distracted but occasionally jotted down notes in response to something I said.

The resultant article is online now. It’s interesting to see which of my remarks were used in the end …and the way that what looks like direct quotes are actually nothing of the kind. Still, that’s way that journalism tends to work���far more of a subjective opinionated approach than simply objectively documenting.

The article focuses a lot on San Francisco, and Richard’s opinions of the scene there. It makes for an interesting read, but it’s a little weird to see quotes attributed to me interspersed amongst a strongly-worded criticism of a city I don’t live in.

Still, the final result is a good read. And I really, really like the liberal sprinkling of hyperlinks throughout���more of this kind of thing in online articles, please!

There is one hyperlink omission though. It’s in this passage where Richard describes what I’m eating as we chatted:

���But here���s the thing I love about this town,��� said Keith, in between bites of a sweet corn fritter, at the festival���s launch party this year. ���It cares as much about art and education as about tech and commerce.���

That sweet corn fritter was from CanTina. Very tasty it was too.

October 28, 2015

Storyforming

It was only last week that myself and Ellen were brainstorming ideas for a combined workshop. Our enthusiasm got the better of us, and we said ���Let���s just do it!��� Before we could think better of it, the room was booked, and the calendar invitations were sent.

The topic was ���story.���

No wait, maybe it was ������narrative.”

That���s not quite right either.

���Content,��� perhaps?

Basically, here���s the issue: at some point everyone at Clearleft needs to communicate something by telling a story. It might be a blog post. It might be a conference talk. It might be a proposal for a potential client. It might be a case study of our work. Whatever form it might take, it involves getting a message across ���using words. Words are hard. We wanted to make them a little bit easier.

We did two workshops. Ellen���s was yesterday. Mine was today. They were both just about two hours in length.

Get out of my head!

Ellen���s workshop was all about getting thoughts out of your head and onto paper. But before we could even start to do that, we had to confront our first adversary: the inner critic.

You know the inner critic. It���s that voice inside you that says ���You���ve got nothing new to say���, or ���You���re rubbish at writing.��� Ellen encouraged each of us to drag this inner critic out into the light���much like Paul Ford did with his AnxietyBox.

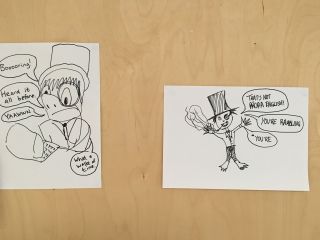

Each of us drew a cartoon of our inner critic, complete with speech bubbles of things our inner critic says to us.

In a bizarre coincidence, Chloe and I had exactly the same inner critic, complete with top hat and monocle.

With that foe vanquished, we proceeded with a mind map. The idea was to just dump everything out of our heads and onto paper, without worrying about what order to arrange things in.

I found it to be an immensely valuable exercise. Whenever I���ve tried to do this before, I���d open up a blank text file and start jotting stuff down. But because of the linear nature of a text file, there���s still going to be an order to what gets jotted down; without meaning to, I���ve imposed some kind of priority onto the still-unformed thoughts. Using a mind map allowed me get everything down first, and then form the connections later.

There were plenty of other exercises, but the other one that really struck me was a simple framework of five questions. Whatever it is that you���re trying to say, write down the answers to these questions about your audience:

What are they sceptical about?

What problems do they have?

What���s different now that you���ve communicated your message?

Paint a pretty picture of life for them now that you���ve done that.

Finally, what do they need to do next?

They���re straightforward questions, but the answers can really help to make sure you���re covering everything you need to.

There were many more exercises, and by the end of the two hours, everyone had masses of raw material, albeit in an unstructured form. My workshop was supposed to help them take that content and give it some kind of shape.

The structure of stories

Ellen and I have been enjoying some great philosophical discussions about exactly what a story is, and how does it differ from a narrative structure, or a plot. I really love Ellen���s working definition: Narrative. In Space. Over Time.

This led me to think that there���s a lot that we can borrow from the world of storytelling���films, novels, fairy tales���not necessarily about the stories themselves, but the kind of narrative structures we could use to tell those stories. After all, the story itself is often the same one that���s been told time and time again���The Hero���s Journey, or some variation thereof.

So I was interested in separating the plot of a story from the narrative device used to tell the story.

To start with, I gave some examples of well-known stories with relatively straightforward plots:

Star Wars,

Little Red Riding Hood,

Your CV,

Jurassic Park, and

Ghostbusters.

I asked everyone to take a story (either from that list, or think of another one) and write the plot down on post-it notes, one plot point per post-it. Before long, the walls were covered with post-its detailing the plot lines of:

Robocop,

Toy Story,

Back To The Future,

Elf,

E.T.,

The Three Little Pigs, and

Pretty Woman.

Okay. That���s plot. Next we looked at narrative frameworks.

Flashback

Begin at a crucial moment, then back up to explain how you ended up there.

e.g. Citizen Kane ���Rosebud!���

Dialogue

Instead of describing the action directly, have characters tell it to one another.

e.g. The Dialogues of Plato ���or The Breakfast Club (or one of my favourite sci-fi short stories).

In Media Res

Begin in the middle of the action. No exposition allowed, but you can drop hints.

e.g. Mad Max: Fury Road (or Star Wars, if it didn���t have the opening crawl).

Backstory

Begin with a looooong zooooom into the past before taking up the story today.

e.g. 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Distancing Effect

Just the facts with no embellishment.

e.g. A police report.

You get the idea.

In a random draw, everyone received a card with a narrative device on it. Now they had to retell the story they chose using that framing. That led to some great results:

Toy Story, retold as a conversation between Andy and his psychiatrist (dialogue),

E.T., retold as a missing person���s report on an alien planet (distancing effect),

Elf, retold with an introduction about the very first Christmas (backstory),

Robocop, retold with Murphy already a cyborg, remembering his past (flashback),

The Three Little Pigs, retold with the wolf already at the door and no explanation as to why there���s straw everywhere (in media res).

Once everyone had the hang of it, I asked them to revisit their mind maps and other materials from the previous day���s workshop. Next, they arranged the ���chunks��� of that story into a linear narrative ���but without worrying about getting it right���it���s not going to stay linear for long. Then, everyone is once again given a narrative structure. Now try rearranging and restructuring your story to use that framework. If something valuable comes out of that, great! If not, well, it���s still a fun creative exercise.

And that was pretty much it. I had no idea what I was doing, but it didn���t matter. It wasn���t really about me. It was about helping others take their existing material and play with it.

That said, I���m glad I finally got this process out into the world in some kind of semi-formalised way. I���ve been preparing talks and articles using these narrative exercises for a while, but this workshop was just the motivation I needed to put some structure on the process.

I think I might try to create a proper deck of cards���along the lines of Brian Eno���s Oblique Strategies or Stephen Andersons���s Mental Notes���so that everyone has the option of injecting a random narrative structural idea into the mix whenever they���re stuck.

At the very least, it would be a distraction from listening to that pesky inner critic.

October 23, 2015

Presentation

Rosa and Charlotte will both be speaking at Bytes Conf here in Brighton next week (don’t bother trying to get a ticket���it’s all sold out).

I’ve been helping them in their preparation, listening to them run through their talks, and offering bits of advice on the content and delivery. Charlotte said she was really nervous presenting to just the two of us. I said “I know what you mean.”

In the past I’ve tried giving practice run-throughs of upcoming conference talks to some of my co-workers at Clearleft. I always found that far more intimidating than giving the talk to room filled with hundreds of strangers.

In fact, just last night I did a practice run of my latest talk at Brighton’s excellent Async gathering, and seeing both Charlotte and Graham in attendance increased my nervousness.

Why is that?

I’ve been thinking about it, and I think it comes down to self-presentation.

We like to think that we have one single personality, but the truth is that we adjust our behaviour constantly to suit the situation. I behave differently when I’m interacting with a shopkeeper than when I’m interacting with my co-workers than when I’m interacting with my family. We adjust how we present ourselves, in subtle and not-so-subtle ways.

If you’re presenting a talk at a conference, it helps to present yourself differently than how you’d present yourself when you’re hanging out with your friends. There’s an element of theatricality���however subtle���in speaking in front of a room full of people. It can really help to slip into a more confident persona.

But if you’re presenting that same talk in a small room to a group of friends, it feels really, really strange to slip into that persona. It feels as strange as interacting with your family as though you were interacting with a shopkeeper.

I think that’s what’s at the root of the discomfort I feel when I try testing a talk on my co-workers. If I present myself in the informal mode I’d usually take with these people, the talk feels all wrong. But if I present myself in my stage persona, it feels weird to do that with these people. So either way, it’s going to feel really strange. Hence the nervousness.

Thing is ���I’m not sure if being aware of this helps in any way.

October 18, 2015

Syndicating to Medium

When I brainpuked my thoughts on Google’s AMP project, I finished up by saying it was one more option for the Indie Web approach to syndication:

When I publish something on adactio.com in HTML, it already gets syndicated to different places. This is the Indie Web idea of POSSE: Publish (on your) Own Site, Syndicate Elsewhere. As well as providing RSS feeds, I���ve also got Twitter bots that syndicate to Twitter. An If This, Then That script pushes posts to Facebook. And if I publish a photo, it goes to Flickr. Now that Medium is finally providing a publishing API, I���ll probably start syndicating articles there as well. The more, the merrier.

Until Medium provided an API, I didn’t see much point in Medium. Let me clarify: I didn’t see much point in it for me. I’ve already got a website where I can publish whatever I like. For someone who doesn’t have their own website, I guess Medium���like Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, etc.���provides a place to publish. I think this is what people mean when they use the word “platform” in a digital���rather than a North Sea oil drilling���sense.

Publishing exclusively on somebody else’s site works pretty well right up until the day the platform turns out to be a trap door and disappears from under you.

But I’m really puzzled by people who already have their own website choosing to publish on Medium instead. A shiny content farm is still a content farm.

“It’s the reach!” I’m told. That makes me sad. The whole point of the World Wide Web is that everybody has an equal opportunity to share their thoughts. You don’t need to ask anyone for permission. The gatekeepers of the previous century���record labels, book publishers, film producers���can’t stop you from making whatever you want and putting it out there for the world to see. And thanks to the principle of net neutrality baked into the design of TCP/IP, no one gets preferential treatment.

Notice that I said “people who already have their own website choosing to publish on Medium instead.” That last bit is important. Using Medium to publish copies of what you’ve already published on your own site gives you the best of both worlds: ownership and reach. That’s what Kevin does, for example. And Jeffrey. Until recently that was quite a pain in the ass, requiring a manual copy’n’paste process.

Back when Medium first launched, Dave Winer said:

Let me enter the URL of something I write in my own space, and have it appear here as a first class citizen. Indistinguishable to readers from something written here.

It still isn’t quite that simple, but now that Medium has a publishing API, it’s relatively straightforward to syndicate copies of your posts to Medium at the moment you publish on your own site.

Here’s what I did…

First of all, I signed up for a Medium account. For the longest time, even this simple step was off-limits for me because Medium used to require authentication using Twitter. By itself, that’s not a problem. The problem was that Medium demanded write permissions for my Twitter account. Just say no.

Now it’s possible to sign up for Medium using email so that rudeness is less of an issue (although I’d really like to see Medium stop being so demanding when it comes to Twitter permissions, especially as the interface copy bends over backwards to promise that Medium would never post to Twitter on my behalf …so why ask for permission to do just that?).

Once I had a Medium account, I needed two pieces of secret information in order to use the API.

The first piece is an access token.

I went to my settings on Medium and scrolled all the way to the bottom to the heading “Integration tokens”. I entered a description (“Syndication from adactio.com”) and pressed the “Get integration token” button.

Now I could use that token to get the second piece of information: my user ID.

I opened up a browser tab and went to this URL: https://api.medium.com/v1/me?accessToken= …adding my new secret integration token to the end.

That returns a JSON response. One of the fields in the JSON object has the name “id”. The value of that field is my user ID on Medium.

With those two pieces of information, I could make an authenticated POST request using cURL. Here’s the PHP code I’m using. It’s probably terrible but please feel free to use it, copy it, fork it, or do anything else you want with it.

When I run that code, I get a JSON response back from Medium’s API. Assuming I get a successful response, I can store the URL of the Medium copy and link out to it from here. That copy on Medium has a corresponding link rel="canonical" in the head of the document pointing back here to adactio.com.

That’s pretty much it. I added a checkbox to my posting interface so that sending a copy of a post to Medium is just a toggle away. I’ll tick that checkbox when I post this. You could be reading this on my site or you could be reading the copy on Medium.

The code I wrote is pretty similar to how I post notes to Twitter and photos to Flickr. In fact, posting to Medium is more straightforward: Flickr requires three bits of secret information; Twitter requires four.

What would make this cross-posting with Medium really interesting would be if it could work in both directions. Then I’d be able to use the (very nice) writing interface on Medium to publish on adactio.com.

That’s not so far-fetched. I’ve already got a micropub endpoint here on my site (here’s the code). That’s how I’m able to use Instagram to post photos to my own site (using OwnYourGram). I let Instagram keep a copy of my photo. I’d be happy to let Medium keep a copy of my post.

We need to break out of the model where all these systems are monolithic and standalone. There���s art in each individual system, but there���s a much greater art in the union of all the systems we create.

October 17, 2015

Mind set

Whenever I have a difference of opinion with someone, I try to see things from their perspective. But sometimes I���m not very good at it. I need to get better.

Here���s an example: I think that users of small-screen touch-enabled devices should be able to pinch-to-zoom content on the web. That idea was challenged twice in recent times:

The initial meta viewport element in AMP HTML demanded that pinch-to-zoom be disabled (it has since been relaxed).

WebKit is removing the 350ms delay on tap ���but only if the page disables pinch-to-zoom (a bug has been filed).

In both cases, I strongly disagreed with the decision to disable what I believe is a vital accessibility feature. But the strength of my conviction is irrelevant. If anything, it is harmful. The case for maintaining accessibility was so obvious to me, I acted as though it were self-evident to everyone. But other people have different priorities, and that���s okay.

I should have stopped and tried to see things from the perspective of the people implementing these changes. Nobody would deliberately choose to remove an important accessibility feature without good reason, so what would those reasons be? Does removing pinch-to-zoom enhance performance? If so, that���s an understandable reason to mandate the strict meta viewport element. I still disagree with the decision, but now when I argue against it, I can approach it from that angle. Instead of dramatically blustering about how awful it is to remove pinch-to-zoom, my time would have been better spent calmly saying ���I understand why this decision has been made, but here���s why I think the accessibility implications are too severe���”

It���s all too easy���especially online���to polarise just about any topic into a binary black and white issue. But of course the more polarised differences of opinion become, the less chance there is of changing those opinions.

If I really want to change someone���s mind, then I need to make the effort to first understand their mind. That���s going to be far more productive than declaring that my own mind is made up. After all, if I show no willingness to consider alternative viewpoints, why should they?

There���s an old saying that before criticising someone, you should walk a mile in their shoes. I���m going to try to put that into practice, and not for the two obvious reasons:

If we still disagree, now we���re a mile away from each other, and

I���ve got their shoes.

October 15, 2015

Someone will read this

After Responsive Field Day I had the chance to spend some extra time in Portland. I was staying with one Andy, with occasional welcome opportunities to hang out with the other Andy.

Over an artisanal, hand-crafted, free-range lunch one day, I took a moment to thank Andy B. I thanked him for a link. Links are very much his stock-in-trade, but there was one in particular that he had shared which stuck in my soul.

It started when he offered a bribe for a good link:

Nidhogg is one of the best local multiplayer games ever. Free Steam code to whoever can show me the best website I’ve never seen before.

��� Andy Baio (@waxpancake) July 30, 2015

Paul Thompson won the bounty:

@waxpancake This is my very favourite: tilde.town/~karlen/

��� Paul Thompson (@Nossidge) July 30, 2015

The link was to a page on Tilde Town, one of the many old-school web rings set up in the spirit of Paul Ford’s Tilde Club. The owner of this page had taken it upon himself to perform a really interesting���and surprisingly moving���experiment:

Find blog posts where people have written “no one will ever read this”, and

Read them aloud.

I’ve written before about how powerful the sound of a human voice can be. There was something about hearing these posts���which were written with a resigned acceptance of indifference���being given the time and respect to be read aloud. I listened to every single one, sometimes bemused, sometimes horrified, always fascinated.

You should listen to all of them too. They deserve it.

One in particular haunted me. It was written in 2008. After listening to it, I had to know more. I felt creepy and voyeuristic, but I transcribed a sentence from the audio file and pasted it in to Google.

I found her blog on the old my-diary.org domain. She only wrote nine entries in total. Her last one was in November 2009.

That was six years ago. I wonder how things turned out for her. I wonder if life got better for her when she left her teenage years behind. I wonder if she ever found peace.

I hope she’s okay.

October 13, 2015

Rosa and Dot

Today is October 13th. It is Ada Lovelace Day:

Ada Lovelace Day is an international celebration of the achievements of women in science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM).

Today is also a Tuesday. That means that Codebar is happening this evening in Brighton:

Codebar is a non-profit initiative that facilitates the growth of a diverse tech community by running regular programming workshops.

The Brighton branch of Codebar is run by Rosa, Dot, and Ryan.

Rosa and Dot are Ruby programmers. They’ve poured an incredible amount of energy into making the Brighton chapter of Codebar such a successful project. They’ve built up a wonderful, welcoming event where everyone is welcome. Whenever I’ve participated as a coach, I’ve always found it be an immensely rewarding experience. For that, and for everything else they’ve accomplished, I thank them.

Brighton is lucky to have them.

October 10, 2015

AMPed up

Apple has Apple News. Facebook has Instant Articles. Now Google has AMP: Accelerated Mobile Pages.

The big players sure are going to a lot of effort to reinvent RSS.

That may sound like a flippant remark, but it’s not too far from the truth. In the case of Apple News, its current incarnation appears to be quite literally an RSS reader, at least until the unveiling of the forthcoming Apple News Format.

Google’s AMP project looks a little bit different to the offerings from Facebook and Apple. Rather than creating a proprietary format from scratch, it mandates a subset of HTML …with some proprietary elements thrown in (or, to use the more diplomatic parlance of the extensible web, custom elements).

The idea is that alongside the regular HTML version of your document, you provide a corresponding AMP HTML version. Because the AMP HTML version will be leaner and meaner, user agents can then grab the AMP HTML version and present that to the end user for a faster browsing experience.

So if an RSS feed is an alternate representation of a homepage or a listing of articles, then an AMP document is an alternate representation of a single article.

Now, my own personal take on providing alternate representations of documents is “Sure. Why not?” Here on adactio.com I provide RSS feeds. On The Session I provide RSS, JSON, and XML. And on Huffduffer I provide RSS, Atom, JSON, and XSPF, adding:

If you would like to see another format supported, share your idea.

Also, each individual item on Huffduffer has a corresponding oEmbed version (and, in theory, an RDF version)���an alternate representation of that item …in principle, not that different from AMP. The big difference with AMP is that it’s using HTML (of sorts) for its format.

All of this sounds pretty reasonable: provide an alternate representation of your canonical HTML pages so that user-agents (Twitter, Google, browsers) can render a faster-loading version …much like an RSS reader.

So should you start providing AMP versions of your pages? My initial reaction is “Sure. Why not?”

The AMP Project website comes with a list of frequently asked questions, which of course, nobody has asked. My own list of invented frequently asked questions might look a little different.

Will this kill advertising?

We live in hope.

Alas, AMP pages will still be able to carry advertising, but in a restricted form. No more scripts that track your movement across the web …unless the script is from an authorised provider, like say, Google.

But it looks like the worst performance offenders won’t be able to get their grubby little scripts into AMP pages. This is a good thing.

Won’t this kill journalism?

Of all the horrid myths currently in circulation, the two that piss me off the most are:

Journalism requires advertising to survive.

Advertising requires invasive JavaScript.

Put the two together and you get the gist of most of the chicken-littling articles currently in circulation: “Journalism requires invasive JavaScript to survive.”

I could argue against the first claim, but let’s leave that for another day. Let’s suppose for now that, sure, journalism requires advertising to survive. Fine.

It’s that second point that is fundamentally wrong. The idea that the current state of advertising is the only way of advertising is incredibly short-sighted and misguided. Invasive JavaScript is not a requirement for showing me an ad. Setting a cookie is not a requirement for showing me an ad. Knowing where I live, who my friends are, what my income level is, and where I’ve been on the web …none of these are requirements for showing me an ad.

It is entirely possible to advertise to me and treat me with respect at the same time. The Deck already does this.

And you know what? Ad networks had their chance. They had their chance to treat us with respect with the Do Not Track initiative. We asked them to respect our wishes. They told us get screwed.

Now those same ad providers are crying because we’re installing ad blockers. They can get screwed.

Anyway.

It is entirely possible to advertise within AMP pages …just not using blocking JavaScript.

For a nicely nuanced take on what AMP could mean for journalism, see Joshua Benton’s article on Nieman Lab���Get AMP’d: Here���s what publishers need to know about Google���s new plan to speed up your website.

Why not just make faster web pages?

Excellent question!

For a site like adactio.com, the difference between the regular HTML version of an article and the corresponding AMP version of the same article is pretty small. It’s a shame that I can’t just say “Hey, the current version of the article is the AMP version”, but that would require that I only use a subset of HTML and that I add some required guff to my page (including an unnecessary JavaScript file).

But for most of the news sites out there, the difference between their regular HTML pages and the corresponding AMP versions will be pretty significant. That’s because the regular HTML versions are bloated with third-party scripts, oversized assets, and cruft around the actual content.

Now it is in theory possible for these news sites to get rid of all those things, and I sincerely hope that they will. But that’s a big political struggle. I am rooting for developers���like the good folks at VOX���who have to battle against bosses who honestly think that journalism requires invasive JavaScript. Best of luck.

Along comes Google saying “If you want to play in our sandbox, you’re going to have to abide by our rules.” Those rules include performance best practices (for the most part���I take issue with some of the requirements, and I’ll go into that in more detail in a moment).

Now when the boss says “Slap a three megabyte JavaScript library on it so we can show a carousel”, the developers can only respond with “Google says No.”

When the boss says “Slap a ton of third-party trackers on it so we can monetise those eyeballs”, the developers can only respond with “Google says No.”

Google have used their influence like this before and it has brought them accusations of monopolistic abuse. Some people got very upset when they began labelling (and later ranking) mobile-friendly pages. Personally, I’ve got no issue with that.

In this particular case, Google aren’t mandating what you can and can’t do on your regular HTML pages; only what you can and can’t do on the corresponding AMP page.

Which brings up another question…

Will the AMP web kill the open web?

If we all start creating AMP versions of our pages, and those pages are faster than our regular HTML versions, won’t everyone just see the AMP versions without ever seeing the “full” versions?

Tim articulates a legitimate concern:

This promise of improved distribution for pages using AMP HTML shifts the incentive. AMP isn���t encouraging better performance on the web; AMP is encouraging the use of their specific tool to build a version of a web page. It doesn���t feel like something helping the open web so much as it feels like something bringing a little bit of the walled garden mentality of native development onto the web.

That troubles me. Using a very specific tool to build a tailored version of my page in order to ���reach everyone��� doesn���t fit any definition of the ���open web��� that I���ve ever heard.

Fair point. But I also remember that a lot of people were upset by RSS. They didn’t like that users could go for months at a time without visiting the actual website, and yet they were reading every article. They were reading every article in non-browser user agents in a format that wasn’t HTML. On paper that sounds like the antithesis of the open web, but in practice there was always something very webby about RSS, and RSS feed readers���it put the power back in the hands of the end users.

Some people chose not to play ball. They only put snippets in their RSS feeds, not the full articles. Maybe some publishers will do the same with the AMP versions of their articles: “To read more, click here…”

But I remember what generally tended to happen to the publishers who refused to put the full content in their RSS feeds. We unsubscribed.

Still, I share the concern that any one company���whether it’s Facebook, Apple, or Google���should wield so much power over how we publish on the web. I don’t think you have to be a conspiracy theorist to view the AMP project as an attempt to replace the existing web with an alternate web, more tightly controlled by Google (albeit a faster, more performant, tightly-controlled web).

My hope is that the current will flow in both directions. As well as publishers creating AMP versions of their pages in order to appease Google, perhaps they will start to ask “Why can’t our regular pages be this fast?” By showing that there is life beyond big bloated invasive web pages, perhaps the AMP project will work as a demo of what the whole web could be.

I’ve been playing around with the AMP HTML spec. It has some issues. The good news is that it’s open source and the project owners seem receptive to feedback.

JavaScript

No external JavaScript is allowed in an AMP HTML document. This covers third-party libraries, advertising and tracking scripts. This is A-okay with me.

The reasons given for this ban are related to performance and I agree with them completely. Big bloated JavaScript libraries are one of the biggest performance killers on the web. I’m happy to leave them at the door (although weirdly, web fonts���another big performance killer���are allowed in).

But then there’s a bit of an about-face. In order to have a valid AMP HTML page, you must include a piece of third-party JavaScript. In this case, the third party is Google and the JavaScript file is what handles the loading of assets.

This seems a bit strange to me; on the one hand claiming that third-party JavaScript is bad for performance and on the other, requiring some third-party JavaScript. As Justin says:

For me this is loading one thing too many��� the AMP JS library. Surely the document itself is going to be faster than loading a library to try and make it load faster.

On the plus side, this third-party JavaScript is loaded asynchronously. It seems to mostly be there to handle the rendering of embedded content: images, videos, audio, etc.

Embedded content

If you want audio, video, or images on your page, you must use propriet… custom elements like amp-audio, amp-video, and amp-img. In the case of images, I can see how this is a way of getting around the browser’s lookahead pre-parser (although responsive images also solve this problem). In the case of audio and video, the standard audio and video elements already come with a way of specifying preloading behaviour using the preload attribute. Very odd.

I���m not sure if this is solving anything at the moment that we���re not already fixing with something like responsive images.

To use amp-img for images within the flow of a document, you’ll need to specify the dimensions of the image. This makes sense from a rendering point of view���knowing the width and height ahead of time avoids repaints and reflows. Alas, in many of the cases here on adactio.com, I don’t know the dimensions of the images I’m including. So any of my AMP HTML pages that include images will be invalid.

Overall, the way that AMP HTML handles embedded content looks like a whole lot of wheel reinvention. I like the idea of providing custom elements as an option for authors. I hate the idea of making them a requirement.

Metadata

If you want to provide metadata about your document, AMP HTML currently requires the use of Google’s Schema.org vocabulary. This has a big whiff of vendor lock-in to it. I’ve flagged this up as an issue and Aaron is pushing a change so hopefully this will be resolved soon.

Accessibility

In its initial release, the AMP HTML spec came with some nasty surprises for accessibility. The biggest is probably the requirement to include this in your viewport meta element:

maximum-scale=1,user-scalable=no

Yowzers! That’s some slap in the face to decent web developers everywhere. Fortunately this has been flagged up and I’m hoping it will be fixed soon.

If it doesn’t get fixed, it’s quite a non-starter. It beggars belief that Google would mandate to authors that they must make their pages inaccessible to pinch/zoom. I would hope that many developers would rebel against such a draconian injunction. If that happens, it’ll be interesting to see what becomes of those theoretically badly-formed AMP HTML documents. Technically, they will fail validation, but for very good reason. Will those accessible documents be rejected?

Please get involved on this issue if this is important to you (hint: this should be important to you).

There are a few smaller issues. Initially the :focus pseudo-class was disallowed in author CSS, but that’s being fixed.

Currently AMP HTML documents must have this line:

body {opacity: 0}body {opacity: 1}

shudders

That’s a horrible conflation of JavaScript availability and CSS. It’s being fixed though, and soon all the opacity jiggery-pokery will only happen via JavaScript, which will be a big improvement: it should either all happen in CSS or all happen in JavaScript, but not the current mixture of the two.

Discovery

The AMP HTML version of your page is not the canonical version. You can specify where the real HTML version of your document is by using rel="canonical". Great!

But how do you link from your canonical page out to the AMP HTML version? Currently you’re supposed to use rel="amphtml". No, they haven’t checked the registry. Again. I’ll go in and add it.

In the meantime, I’m also requesting that the amphtml value can be combined with the alternate value, seeing as rel values can be space separated:

rel="alternate amphtml" type="text/html"

See? Not that different to RSS:

rel="alterate" type="application/rss+xml"

POSSE

When I publish something on adactio.com in HTML, it already gets syndicated to different places. This is the Indie Web idea of POSSE: Publish (on your) Own Site, Syndicate Elsewhere. As well as providing RSS feeds, I’ve also got Twitter bots that syndicate to Twitter. An If This, Then That script pushes posts to Facebook. And if I publish a photo, it goes to Flickr. Now that Medium is finally providing a publishing API, I’ll probably start syndicating articles there as well. The more, the merrier.

From that perspective, providing AMP HTML pages feels like just one more syndication option. If it were the only option, and I felt compelled to provide AMP versions of my content, I’d be very concerned. But for now, I’ll give it a whirl and see how it goes.

Here’s a bit of PHP I’m using to convert a regular piece of HTML into AMP HTML���it’s horrible code; it uses regular expressions on HTML which, as we all know, will summon the Elder Gods.

Jeremy Keith's Blog

- Jeremy Keith's profile

- 55 followers