Martin Fowler's Blog, page 27

June 23, 2016

Bliki: BoiledCarrot

I hated carrots when I was growing up, hating the smell and texture of the things.

But after I left home and started to cook for myself I started to like them. Nothing

changed about the carrots, nor did my taste buds get a radical overhaul, the

difference was in the cooking. My mother, like so many English people of her

generation, wasn't a great cook - particularly of vegetables. Her approach was to boil

carrots for twenty minutes or more. I since learned that if you cook them properly,

carrots are a totally different experience.

This isn't a site about cooking, but about software development. But I find that

often a technique or tool is like the poor carrot - blamed for being awful when the

real problem is that the technique is being done incorrectly.

Let's take a couple of examples. Several friends of mine

commented how stored procedures were a disaster because they weren't

kept in version control (instead they had names like GetCust01,

GetCust02, GetCust02B etc). That's not a problem with stored

procedures, that's a problem with people using bad practices with them.

Similarly a criticism that TDD led to a brittle design on further

questioning led to the discovery that the team in question hadn't done

any refactoring - and refactoring is a critical step in TDD.

Both of these are boiled carrots - useful tools that have been misused. I've seen

teams gain value out of both stored procedures and TDD. If we discard them without

taking their usage into account we lose useful tools from our toolbox.

Not every failure of technique is a boiled carrot. I'm reliably informed that there's

no way to cook squirrels so they are appetizing to anyone who isn't desperate (which is

a shame considering what they've been doing to our garden this spring). If I come across

a team working on code in a shared folder, without any version control, there's no way

to cook that technique which isn't similarly appalling.

So when we hear of techniques failing, we need to ask a lot

more questions.

Was it the technique itself that had problems, or was some

other thing being missed out. Does the technique have an influence on

this? (Version control is a separate thing to stored procedures, but

it can be harder to use version control with stored procedures due to

nature of tools involved.)

Was the technique used in a context that wasn't suitable for

it? (Don't use wide-scale manual refactoring when you don't have

tests.) Remember that software development is a very human activity,

often techniques aren't suitable for a context because of culture and

personality.

Were important pieces missed out of the technique?

Were people focused on outward signs that didn't correspond to

the reality? This kind of thing is what Steve McConnell called Cargo Cult

Software Engineering.

Is the technique something that works at some scale, but is being used outside its

zone of applicability? It's worth remembering Paracelsus's principle that the

difference between a medicine and a poison is the dosage. Testing a system through the

UI is useful with a few scenarios, but if you use it as your main testing approach

you'll end up with slow and brittle tests which will either slow you down or get ignored.

An interesting aspect of this is whether certain techniques are

fragile; i.e are they hard to apply correctly and thus more prone

to a faulty application? If it's hard to use a technique properly,

that's a reasonable limitation on the technique, reducing the context

when it can be used. Some delicate foods have to left to a master chef. That doesn't

make them a bad technique, but it does reduce their applicability to more skillful

teams. I'd argue this is the fundamental problem with late integration of components.

While some teams can develop components to careful specifications that can integrate

together late in the day, in practice few teams are able to pull that off, and late

integration ends up being like Fugu.

While we need to be wary of boiled carrots, we also need to bear in mind we also get

the situation that I've observed as "no methodology has ever failed". With any failure

(assuming you can know WhatIsFailure) you can find some variation from the

methodology - which leads its defenders to say it wasn't followed and thus didn't fail.

There's a genuine tension here, one that can't be resolved without a deep understanding

of the deeper principles underlying a technique. The real point is that such techniques

aren't rigorously describable, just as Spaghetti Carbonara does not have one precise

recipe that can be followed without thinking. In the end what really counts is the dish,

the technique to prepare it can inspire and guide a good chef but cannot guarantee

success to someone without a certain degree of skill.

Like any profession, we can advance faster if we learn from each others' experiences.

Reports of people using techniques and tools are important so that we can judge what to

try in our own work. However a simple label usually isn't enough to go on. We are as

unable to measure compliance with the proper use of a technique as we are unable to

measure their successfulness. The important thing to do is whenever you hear of a

technique failing - always dig deeper to see if the carrot's been in the pot

too long. Otherwise we risk missing out on something worthwhile.

I originally wrote about this topic under the heading "Faulty Technique Dichotomy", but

now feel the boiled carrot metaphor is more memorable.

Further Reading

I liked Ron Jeffries parable for a similar phenomenon "We tried baseball and it didn't

work".

Acknowledgements

Henrique Souza, Jeantine Mankelow, Karl Brown, Kief Morris, Kyle Hodgson, Matteo

Vaccari, Patrick Kua, Rebecca Parsons, Ricardo Cavalcanti, Roni Greenwood, Sriram Narayan,

and Steven Lowe

discussed drafts of this post on our internal mailing list.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

June 21, 2016

Bliki: BimodalIT

Bimodal IT is the flawed notion that software systems should be divided into these

two distinct categories for management and control.

Front Office systems should be optimized for rapid feature development. These systems

of engagement need to react rapidly to changing customer needs and business

opportunities. Defects should be tolerated as the necessary cost for this rapid

development cycle.

Back Office systems should be optimized for reliability. As systems of record, it's

important that you don't get defects that damage the enterprise. Consequently you slow

down the rate of change.

The term Bimodal IT is used by Gartner [1]. McKinsey and Co talk about the same basic idea under the name "Two Speed IT". (I find it hard to resist calling it "Bipolar IT".)

When I first heard about this approach, I was pleased - thinking that these august

organizations had come to same conclusion that I had with my

UtilityVsStrategicDichotomy, but as I read further I realized that Bimodal IT

was a different animal. And worse I think that Bimodal IT is really a path down the

wrong direction.

My first problem is that the separation is based on software systems rather than

business activity. If you want to rapidly cycle new ideas, you are going to need to

modify the back office systems of record just as frequently as the front office systems of

engagement. You can't come up with clever pricing plans without modifying the systems of

record that support them.

My second issue is that the bimodal idea is founded on the

TradableQualityHypothesis, the idea that quality is something you trade-off

for speed. It's a common notion, but a false one. One of the striking things that we

learned at ThoughtWorks when we started using agile approaches for rapid feature

delivery is that we also saw a dramatic decline in production defects. It's not uncommon

to see us go live with an order of magnitude fewer defects than is usual for our

clients, even in their systems of record. The key point is that high quality (and low

defects) are a crucial enabler for rapid cycle-time. By not paying attention to quality,

people following a bimodal approach will actually end up slowing down their pace of

innovation in their "systems of engagement".

So my advice here that it is wise to use different management approaches to different

kinds of software projects, but don't make this distinction based on the bimodal

approach. Instead take a BusinessCapabilityCentric approach, and look at

whether your business capabilities are utility or strategic.

Further Reading

Sriram Narayan's book - Agile IT Organization Design

- looks at this kind of problem in much more depth.

Jez Humble provides a worthwhile critique of Bimodal IT

Simon Wardley prefers

a three-level model of Pioneers, Settlers, and Town Planners.

Notes

1:

Sadly all their substantial material is available to subscribers only.

Acknowledgements

Brian Oxley, Dave Elliman, Jonny LeRoy, Ken McCormack, Mark Taylor, Patrick Kua, Paulo

Caroli, and Praful J Todkar

discussed drafts of this post on our internal mailing list

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

June 20, 2016

Bliki: Serverless

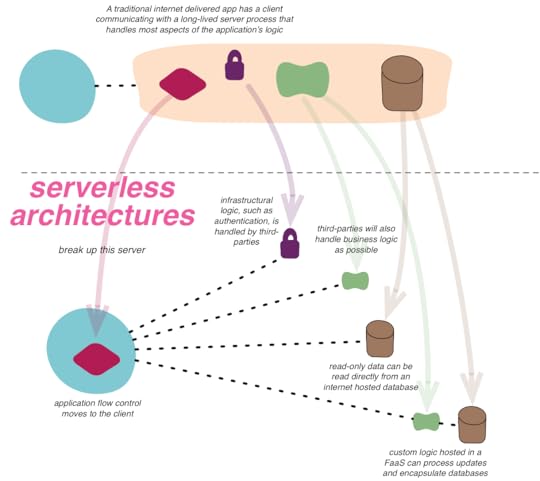

Serverless architectures are internet based systems where the application development

does not use the usual server process. Instead they rely solely on a combination of

third-party services, client-side logic, and service hosted remote procedure calls

(FaaS).

Serverless applications often make extensive use of third party services to

accomplish tasks that are traditionally taken care of by servers. These services could

be rich ecosystems of services that interoperate, such as Amazon AWS and Azure, or they could be a single service that

attempt to provide turnkey set of capabilities such a Parse or Firebase.

The abstraction provided by these services could be infrastructural (such as message

queues, databases, edge caching…) or higher-level (federated identify, role and

capability management, search…).

One of the primary responsibilities of a general purpose server based web application

is to control the request-response cycle. Controllers on the server side process input,

invoke appropriate application behaviour and construct dynamic responses, typically

using a templating engine. In a serverless application, where application behaviour is

woven together from third party services, client side control flow and dynamic

content generation replaces the server side controllers. Rich Javascript

applications, mobile applications (and increasingly, TV or embedded IoT applications)

coordinate the interaction between the various services by making API calls and using

client side UI frameworks to the generate dynamic content.

The most substantive part of a server based web application is the work that happens

between the controller and the infrastructure; the business logic. A long lived server

hosts the code that implements this logic and performs the required processing for as

long as the application stays alive. In serverless applications, custom code

components have a lifecycle that is much shorter, closer to the timeline of a single

HTTP request/response cycle. The code activates when a request arrives, processes the

request and becomes dormant as soon as the activity dies down. This code often lives in

a managed environment such as Amazon

Lambda, Azure

Function or Google Cloud

Functions, which takes care of the lifecycle management and scaling of the code.

(This style of organizing software is sometimes called “Function as a

Service” - FaaS.) The short per-request lifecycle offers itself to a per-request

pricing model too, which results in significant cost savings for some teams. [1]

A new style, a new set of tradeoffs

All design is about tradeoffs. There are some distinct advantages to applications

built in this style and certainly some problems too.

The most commonly asserted benefit is cost. In systems with bursty traffic patterns, the cost of having a beefy server run cold the majority of the time in order to accomodate the bursts is both wasteful and expensive. The demand based pricing model of cloud based infrastructure services can offer significant reduction in costs for teams that have to deal with this type of traffic. In addition, in a traditional server based application the scalability of the application and all associated infrastructural components are the responsibility of the development team. This is often harder than using services that scale transparently behind the simple abstraction of an API available over a URL. Thus teams often find that it serverless applications can be made to scale more easily.

On the other hand, there are some new costs. The conceptual overhead of splitting a single application into something that woven from a fabric of services is significant and increases with the number and variety of services used. Local development and unit testing is also harder when applications have significant parts implemented and running in external services. Teams often use Broad Stack Tests and semantic monitoring to offset this to some extent.

Lastly, there is a perceived benefit of serverless systems being easier to

operate and maintain. Third-party services spend significant resources on

security, availability, scaling and performance. These things often require

specialized skills and may not be in the wheelhouse of smaller development teams. But

this doesn't mean teams can forget about operations. It still falls on development

teams to deal with the problems caused by service outage, downtime, decomissioning

and slowdowns and to prevent these from having a cacading impact on their own

applications.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Martin Fowler for his help with the illustration, editorial advice and guidance with this post. In addition, many thanks to Mike Roberts, Paul Hammant and Ken McCormack for their input and to Chris Turner, Ian Carvell, Patrick Debois and Jay Sandhaus for taking time to discuss their experiences building serverless applications.

Further Reading

Mike Roberts is writing a more detailed

article on serverless architectures, which includes examples, further

details on trade-offs and contrast with similar styles.

Patrick Debois talks more about the reality of operations for serverless

architectures in his talk from serverlessconf

2016

Notes

1:

Other automation services such as Zapier and IFTTT seem to foreshadow in spirit, if not in their

developer friendliness, the sort of things that can be done with AWS Lambda, Azure

Function or Google Cloud Functions.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

June 19, 2016

photostream 99

June 17, 2016

What isn't Serverless

Serverless architectures often get tangled with PaaS or are thought of as a

#NoOps approach that gets rid of operational demands. Mike's article now looks at

those comparisons.

June 16, 2016

Bliki: YAaaS

YAaaS: Yet Another as a Service

These days everything seems to need to be "as a service", so we need a meta-term

for this linguistic trend. My thanks to my colleague Birgitta Böckeler for coming up with one. So

now we can say things like "FaaS is a YAaaS for 'Function'".

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

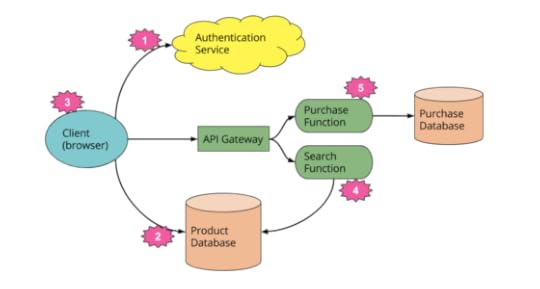

Unpacking FaaS

Mike introduced the notion of Function as a Service (FaaS) in the first part of

his serverless article. In this installment he expands on this, unpacking Amazon's

description of their Lambda product to develop a general definition of FaaS. This

includes important characteristics around state, execution duration, startup

latency, and the role of API Gateways.

June 15, 2016

Serverless Architectures

One of the latest architectural styles to appear on the internet is that of

Serverless Architectures, which allow teams to get rid of the traditional server

engine that sits behind their web and mobile applications. Mike Roberts has been working with teams

that have using this approach and has started writing an evolving article to

explain this style and how to use it. He begins with describing what "serverless"

means - with a couple of examples of how more usual designs become serverless.

June 11, 2016

photostream 98

June 8, 2016

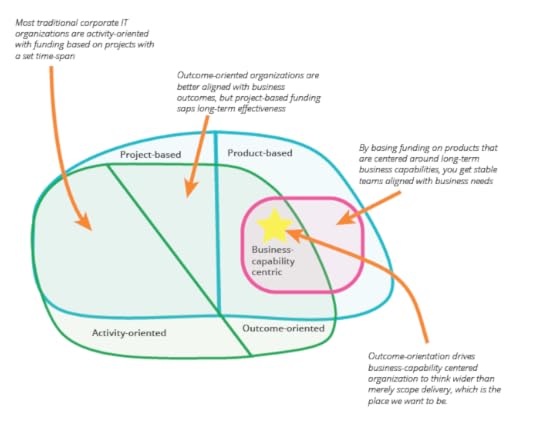

Bliki: BusinessCapabilityCentric

A business-capability centric team is one whose work is aligned long-term to a

certain area of the business. The team lives as long as the said business-capability is

relevant to the business. This is in contrast to project teams that only last as long as

it takes to deliver project scope.

For example, an e-commerce business has capabilities such as buying and

merchandising, catalog, marketing, order management, fulfilment and customer service.

An insurance business has capabilities such as policy administration, claims

administration, and new business. A telecom business has capabilities such as network

management, service provisioning and assurance, billing, and revenue management. They

may be further divided into fine-grained capabilities so that they can be owned by teams

of manageable size.

Business-capability centric teams are “think-it, build-it and run-it” teams. They do

not hand over to other teams for testing, deploying or supporting what they build. They

own problems in their area end-to-end. They also own the IT systems (applications, APIs

and data) that primarily support the business-capability. The underlying technology

platforms (e.g. Java, .NET) and application platforms (e.g. Salesforce, SAP, Peoplesoft)

may be shared across teams.

Sriram's book goes into more detail on how and why to build a business-capability

centric IT organization.

The team size for each capability is determined periodically, such as annually, based

on guidance from IT strategy. This is a

different kind of portfolio management where budget in the form of team capacity is allocated

across a portfolio of long-lived business-capabilities whereas in traditional portfolio management,

budget in the form of funds is allocated across a portfolio of comparatively short-lived projects/programs.

Business-capability centric teams need to be OutcomeOriented to maximize their

potential. Unless they are empowered to work towards a business outcome, they may

devolve to being scope-delivery oriented.

Consider the example of a typical application landscape with a mix of up-to-date and

legacy systems, some homegrown applications and some commercial off-the-shelf (COTS)

applications, some SaaS applications, a heterogeneous API layer served by some new

microservices, some mega-services and everything tied together with a combination of

ad-hoc integration, an enterprise service bus and other boutique middleware. Each

business-capability centric team would own a cohesive subset of the above that primarily

relates to its business area. However, some applications are cross-capability by nature

e.g. the end-to-end lookup-to-checkout customer journey in an e-commerce application.

They might need a team of their own (or two teams, one for mobile and one for the

laptop). It is a non-trivial exercise to draw boundaries within the application

landscape and parcel it out to teams. Outcome-orientation is a good guiding principle.

Consider if each parcel can be held responsible for a business outcome or sub-outcome

(expressed as a business metric).

Some people are concerned that having a single team manage several systems within a

business capability will act against Conway’s Law. But Conway's law isn't against a

single team being responsible for multiple related components. It allows for high

cohesion of component ownership and low coupling between teams and thus makes for better

responsiveness.

Implications for Headcount

A business-capability centric configuration may require a slightly greater

headcount than a project-centric model of execution. This is because a project’s remit

is typically only to “build-it, handover to support/ops and disband” while a

business-capability centric team’s remit is to “think-it, build-it and run-it” for as

long as the business-capability is relevant. This requires us to maintain at least a

minimal team at all times for each business-capability. As it turns out, this is

desirable for a number of reasons. The project-centric model usually ends up

compromising the architectural integrity of the application landscape because each

project team only cares about delivering its scope by the promised date. In the

process, it may take shortcuts such as:

Ad-hoc integrations with the systems it depends on

Integrating with or adding functionality to systems that are meant to be sunsetted

because it would take more effort to do so with the replacement systems.

Tacking on quick-and-dirty code on top of a previous team’s efforts and making it a

maintenance nightmare in the process.

Some of this may be avoided with capable oversight from enterprise architecture but it

remains a challenge nevertheless because the project-centric model often results in a

different team for every new release and the new teams have to learn business rules and

do’s and don’ts of the surrounding application landscape all over again. Outsourcing

complicates this further.

On the other hand, the project-centric model is no stranger to huge headcounts when

funding is plentiful and projects are initiated recklessly without regard to the carrying

capacity of the existing codebase and application landscape. The lack of work-in-process

limits at a project portfolio level leads to many projects getting started and few

finishing or delivering desired outcomes.

Strategic and Utility Capabilities

Business capabilities may be categorized as

strategic or utility

over a given time horizon. Sometimes, it is more useful to label a few sub-capabilities within a capability as strategic.

On the other hand, corporate IT capabilities such as payroll, accounting, legal, HR and workplace collaboration are usually

classified as utility. Although still organized as business-capability centric teams, utility capabilities

are often delivered with packaged software (buy over build). So they are "think-it, buy-it, customize/configure/integrate-it, run-it"

teams rather than "think-it, build-it, run-it" teams. Utility capabilities are also commonly outsourced to external

business-capability centric teams supplied by managed service providers. Even when delivered in-house, it is

practical to staff these teams for keep-the-lights-on skills rather than top-notch development skills. In the same vein,

although outcome-orientation is important for utility capabilities, they could be led by lower grade product owners.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Martin Fowler for his guidance with the content, help with publishing and for the nice illustrations.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1103 followers