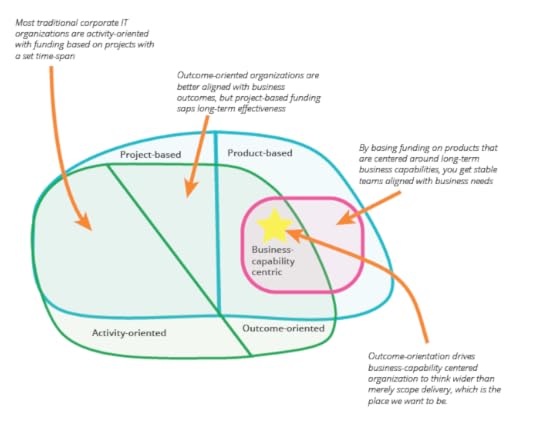

Bliki: BusinessCapabilityCentric

A business-capability centric team is one whose work is aligned long-term to a

certain area of the business. The team lives as long as the said business-capability is

relevant to the business. This is in contrast to project teams that only last as long as

it takes to deliver project scope.

For example, an e-commerce business has capabilities such as buying and

merchandising, catalog, marketing, order management, fulfilment and customer service.

An insurance business has capabilities such as policy administration, claims

administration, and new business. A telecom business has capabilities such as network

management, service provisioning and assurance, billing, and revenue management. They

may be further divided into fine-grained capabilities so that they can be owned by teams

of manageable size.

Business-capability centric teams are “think-it, build-it and run-it” teams. They do

not hand over to other teams for testing, deploying or supporting what they build. They

own problems in their area end-to-end. They also own the IT systems (applications, APIs

and data) that primarily support the business-capability. The underlying technology

platforms (e.g. Java, .NET) and application platforms (e.g. Salesforce, SAP, Peoplesoft)

may be shared across teams.

Sriram's book goes into more detail on how and why to build a business-capability

centric IT organization.

The team size for each capability is determined periodically, such as annually, based

on guidance from IT strategy. This is a

different kind of portfolio management where budget in the form of team capacity is allocated

across a portfolio of long-lived business-capabilities whereas in traditional portfolio management,

budget in the form of funds is allocated across a portfolio of comparatively short-lived projects/programs.

Business-capability centric teams need to be OutcomeOriented to maximize their

potential. Unless they are empowered to work towards a business outcome, they may

devolve to being scope-delivery oriented.

Consider the example of a typical application landscape with a mix of up-to-date and

legacy systems, some homegrown applications and some commercial off-the-shelf (COTS)

applications, some SaaS applications, a heterogeneous API layer served by some new

microservices, some mega-services and everything tied together with a combination of

ad-hoc integration, an enterprise service bus and other boutique middleware. Each

business-capability centric team would own a cohesive subset of the above that primarily

relates to its business area. However, some applications are cross-capability by nature

e.g. the end-to-end lookup-to-checkout customer journey in an e-commerce application.

They might need a team of their own (or two teams, one for mobile and one for the

laptop). It is a non-trivial exercise to draw boundaries within the application

landscape and parcel it out to teams. Outcome-orientation is a good guiding principle.

Consider if each parcel can be held responsible for a business outcome or sub-outcome

(expressed as a business metric).

Some people are concerned that having a single team manage several systems within a

business capability will act against Conway’s Law. But Conway's law isn't against a

single team being responsible for multiple related components. It allows for high

cohesion of component ownership and low coupling between teams and thus makes for better

responsiveness.

Implications for Headcount

A business-capability centric configuration may require a slightly greater

headcount than a project-centric model of execution. This is because a project’s remit

is typically only to “build-it, handover to support/ops and disband” while a

business-capability centric team’s remit is to “think-it, build-it and run-it” for as

long as the business-capability is relevant. This requires us to maintain at least a

minimal team at all times for each business-capability. As it turns out, this is

desirable for a number of reasons. The project-centric model usually ends up

compromising the architectural integrity of the application landscape because each

project team only cares about delivering its scope by the promised date. In the

process, it may take shortcuts such as:

Ad-hoc integrations with the systems it depends on

Integrating with or adding functionality to systems that are meant to be sunsetted

because it would take more effort to do so with the replacement systems.

Tacking on quick-and-dirty code on top of a previous team’s efforts and making it a

maintenance nightmare in the process.

Some of this may be avoided with capable oversight from enterprise architecture but it

remains a challenge nevertheless because the project-centric model often results in a

different team for every new release and the new teams have to learn business rules and

do’s and don’ts of the surrounding application landscape all over again. Outsourcing

complicates this further.

On the other hand, the project-centric model is no stranger to huge headcounts when

funding is plentiful and projects are initiated recklessly without regard to the carrying

capacity of the existing codebase and application landscape. The lack of work-in-process

limits at a project portfolio level leads to many projects getting started and few

finishing or delivering desired outcomes.

Strategic and Utility Capabilities

Business capabilities may be categorized as

strategic or utility

over a given time horizon. Sometimes, it is more useful to label a few sub-capabilities within a capability as strategic.

On the other hand, corporate IT capabilities such as payroll, accounting, legal, HR and workplace collaboration are usually

classified as utility. Although still organized as business-capability centric teams, utility capabilities

are often delivered with packaged software (buy over build). So they are "think-it, buy-it, customize/configure/integrate-it, run-it"

teams rather than "think-it, build-it, run-it" teams. Utility capabilities are also commonly outsourced to external

business-capability centric teams supplied by managed service providers. Even when delivered in-house, it is

practical to staff these teams for keep-the-lights-on skills rather than top-notch development skills. In the same vein,

although outcome-orientation is important for utility capabilities, they could be led by lower grade product owners.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Martin Fowler for his guidance with the content, help with publishing and for the nice illustrations.

Share:

if you found this article useful, please share it. I appreciate the feedback and encouragement

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1103 followers