Martin Fowler's Blog, page 13

January 13, 2020

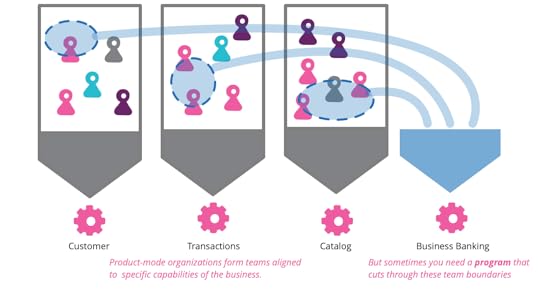

How to manage a program in a product-mode organization

My colleagues often talk about the important advantages of organizing a

software development organization using products rather than projects.

While this is an effective organizational approach, it does have its

downsides. One of these is handling programs that require coordinating

across multiple product teams. Luiza Nunes and James Lewis share their

experiences dealing with this situation, outlining the kinds of problems

they see and the practices they've found to make it work.

November 18, 2019

Bliki: ExploratoryTesting

Exploratory testing is a style of testing that emphasizes a rapid cycle of

learning, test design, and test execution. Rather than trying to verify that

the software conforms to a pre-written test script, exploratory testing

explores the characteristics of the software, raising discoveries that will then be

classified as reasonable behavior or failures.

The exploratory testing mindset is a contrast to that of scripted

testing. In scripted testing, test designers create a script of tests, where

each manipulation of the software is written down, together with the expected

behavior of the software. These scripts are executed separately, usually many

times, and usually by different actors than those who wrote them. If any test

demonstrates behavior that doesn't match the expected behavior designed by the

test, then we consider this a failure.

For a long time scripted tests were usually executed by testers,

and you'd see lots of relatively junior folks in cubicles clicking through

screens following the script and checking the result. In large part due to the

influence of communities like Extreme Programming, there's been a

shift to automating scripted testing. This allows the tests to be executed

faster, and eliminates the human error involved in evaluating the expected

behavior. I've long been a firm advocate of automated testing like this, and

have seen great success with its use drastically reducing bugs.

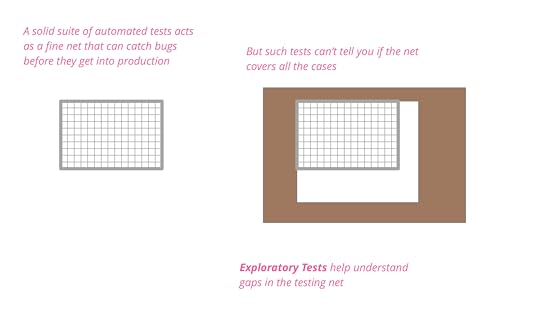

But even the most determined automated testers realize that there are

fundamental limitations with the technique, which are limitations of any form

of scripted testing. Scripted testing can only verify what is in the script,

catching only conditions that are known about. Such tests can be a fine net that

catches any bugs that try to get through it, but how do we know that the net

covers all it ought to?

Exploratory testing seeks to test the boundaries of the net, finding new

behaviors that aren't in any of the scripts. Often it will find new failures

that can be added to the scripts, sometimes it exposes behaviors that are

benign, even welcome, but not thought of before.

Exploratory testing is a much more fluid and informal process than scripted

testing, but it still requires discipline to be done well. A good way to do

this is to carry out exploratory testing in time-boxed sessions. These

sessions focus on a particular aspect of the software. A charter that

identifies the target of the session and what information you hope to find is

a fine mechanism to provide this focus.

Elisabeth Hendrickson is

one of the most articulate exponents of exploratory testing, and her book is the first choice to dig for more

is the first choice to dig for more

information on how to do this well.

Such a charter can act as focus, but shouldn't attempt to define details of

what will happen in the session. Exploratory testing involves trying things,

learning more about what the software does, applying that learning to generate

questions and hypotheses, and generating new tests in the moment to gather

more information. Often this will spur questions outside the bounds of the

charter, that can be explored in later sessions.

Exploratory testing requires skilled and curious testers, who are

comfortable with learning about the software and coming up with new test

designs during a session. They also need to be observant, on the lookout for

any behavior that might seem odd, and worth further investigation. Often,

however, they don't have to be full-time testers. Some teams like to have the

whole team carry out exploratory testing, perhaps in pairs or in a single mob.

Exploratory testing should be a regular activity occurring throughout the

software development process. Sadly it's hard to find any guidelines on how

much should be done within a project. I'd suggest starting with a one hour

session every couple of weeks and see what kinds of information the sessions

unearth. Some teams like to arrange half-an-hour or so of exploratory testing

whenever they complete a story.

If you find bugs are getting through to production, that's a

sign that there are gaps in the testing regimen. It's worth looking at any bug

that escapes to production and thinking about what measures could be taken to

either prevent the bug from getting there, or detecting it rapidly when in

production. This analysis will help you decide whether you need more

exploratory testing. Bear in mind

that it will take time to build up the skill to do exploratory testing well, if you haven't

done much exploratory testing before.

I would consider it a red flag if a team

isn't doing exploratory testing at all - even if their automated testing was

excellent. Even the best automated testing is inherently scripted testing -

and that alone is not good enough.

Acknowledgements

Almost all I know about Exploratory Testing comes from Elisabeth

Hendrickson's fine book , which is also where I

, which is also where I

pinched the net metaphor from.

Aida Manna, Alex Fraser, Bharath Kumar Hemachandran, Chris Ford, Claire

Sudbery, Daniel Mondria, David Corrales, David Cullen, David Salazar

Villegas, Lina Zubyte, and Philip Peter

discussed drafts of this article on our internal mailing list.

November 12, 2019

Bliki: WaterfallProcess

In the software world, “waterfall” is commonly used to describe a style of

software process, one that contrasts with the ideas of iterative,

or agile styles. Like many well-known terms in software it's meaning is

ill-defined and origins are obscure - but I find its essential theme is

breaking down a large effort into phases based on activity.

It's not clear how the word “waterfall” became so prevalent, but most

people base its origin on a paper by Winston

Royce, in particular this figure:

Although this paper seems to be universally acknowledged as the source of

the notion of waterfall (based on the shape of the downward cascade of tasks),

the term “waterfall” never appears in the paper. It's not clear how the name

appeared later.

Royce’s paper describes his observations on the software development

process of the time (late 60s) and how the usual implementation steps could be

improved. [1] But “waterfall” has gone much

further, to be used as a general description of a style of software

development. For people like me, who speak at software conferences, it almost

always only appears in a derogatory manner - I can’t recall hearing any

conference speaker saying anything good about waterfall for many years.

However when talking to practitioners in enterprises I do hear of it spoken as

a viable, even preferred, development style. Certainly less so now that in the

90s, but more frequently than one might assume by listening to process

mavens.

But what exactly is “waterfall”? That’s not an easy question to answer as,

like so many things in software, there is no clear definition. In my

judgment, there is one common characteristic that dominates any definition

folks use for waterfall, and that’s the idea of decomposing effort into phases

based on activity.

Let me unpack that phrase. Let’s say I have some software to build, and I

think it’s going to take about a year to build it. Few people are going to

happily say “go away for a year and tell me when its done”. Instead, most

people will want to break down that year into smaller chunks, so they can

monitor progress and have confidence that things are on track. The question

then is how do we perform this break down?

The waterfall style, as suggested by the Royce sketch, does it by the

activity we are doing. So our 1 year project might be broken down into 2

months of analysis, followed by 4 months design, 3 months of coding, and 3

months of testing. The contrast here is to an iterative style, where we would

take some high level requirements (build a library management system), and

divide them into subsets (search catalog, reserve a book, check-out and

return, assess fines). We'd then take one of these subsets and spend a couple

of months to build working software to implement that functionality,

delivering either into a staging environment or preferably into a live

production setting. Having done that with one subset, we'd continue with

further subsets.

In this thinking waterfall means “do one activity at a time for all the

features” while iterative means “do all activities for one feature at a time”.

If the origin of the word “waterfall” is murky, so is the notion of how

this phase-based breakdown originated. My guess is that it’s natural to break

down a large task into different activities, especially if you look to

activities such as building construction as an inspiration. Each activity

requires different skills, so getting all the analysts to complete analysis

before you bring in all the coders makes intuitive sense. It seems

logical that a misunderstanding of requirements is cheaper to fix before

people begin coding - especially considering the state of computers in the

late 60s. Finally the same activity-based breakdown can be used as a standard

for many projects, while a feature-based breakdown is harder to teach. [2]

Although it isn’t hard to find people explain why this waterfall thinking

isn’t a good idea for software development, I should summarize my primary

objections to the waterfall style

here.

The waterfall style usually has testing and integration as two of the final

phases in the cycle, but these are the most difficult to predict elements in a

development project. Problems at these stages lead to rework of many steps of

earlier phases, and to significant project delays. It's too easy to declare

all but the late phases as "done", with much work missing, and thus it's hard

to tell if the project is going well.

There is no opportunity for early releases before all features are done. All this

introduces a great deal of risk to the development effort.

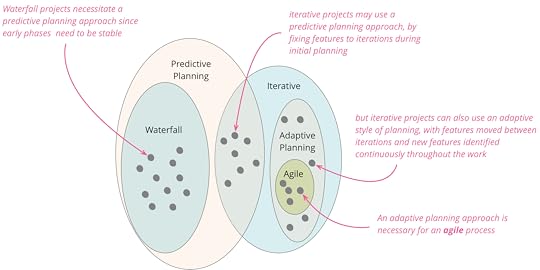

Furthermore, a waterfall approach forces us into a predictive style of

planning, it assumes that once you are done with a phase, such as requirements

analysis, the resulting deliverable is a

stable platform for later phases to base their work on. [3] In practice the vast

majority of software projects find they need to change their requirements

significantly within a few months, due to everyone learning more about the

domain, the characteristics of the software environment, and changes in the

business environment. Indeed we've found that

delivering a subset of features does more than anything to help clarify what

needs to be done next, so an iterative approach allows us to shift to an

adaptive planning approach where we update our plans as we learn what the

real software needs are. [4]

These are the major reasons

why I've glibly said that "you should use iterative development only in projects that

you want to succeed".

Waterfalls and iterations may nest inside each other. A six year project

might consist of two 3 year projects, where each of the two projects are

structured in a waterfall style, but the second project adds additional

features. You can think of this as a two-iteration project at the top level

with each iteration as a waterfall. Due to the large size and small number of

iterations, I'd regard that as primarily a waterfall project. In contrast you

might see a project with 16 iterations of one month each, where each

iteration is planned in a waterfall style. That I'd see as primarily

iterative. While in theory there's potential for a middle ground projects that

are hard to classify, in practice it's usually easy to tell that one style

predominates.

It is possible for a mix of waterfall and iterative where early phases

(requirements analysis, high level design) are done in a waterfall style while

later phases (detailed design, code, test) are done in an iterative manner.

This reduces the risks inherent in late testing and integration phases, but

does not enable adaptive planning.

Waterfall is often cast as the alternative to agile software development,

but I don't see that as strictly true. Certainly agile processes require an

iterative approach and cannot work in a waterfall style. But it is easy to

follow an iterative approach (i.e. non-waterfall) but not be agile. [5] I might do

this by taking 100 features and dividing them up into ten iterations over the

next year, and then expecting that each iteration should complete on time with

its planned set of features. If I do this, my initial plan is a predictive

plan, if all goes well I should expect the work to closely follow the plan. But

adaptive planning is an essential element of

agile thinking. I expect features to move between iterations, new features to

appear, and many features to be discarded as no longer valuable enough.g

My rule of thumb is that anyone who

says “we were successful because we were on-time and on-budget” is

thinking in terms of predictive planning, even if they are following an

iterative process, and thus is not thinking with an agile mindset.

In the agile world, success is all about business value - regardless of what

was written in a plan months ago. Plans are made, but updated regularly. They guide

decisions on what to do next, but are not used as a success measure.

Notes

1:

There have been quite a few people seeking to interpret the Royce paper.

Some argue that his paper opposes waterfall, pointing out that the

paper discusses flaws in the kind of process suggested by the figure 2

that I've quoted here. Certainly he does discuss flaws, but he also says

the illustrated approach is "fundamentally sound". Certainly this

activity-based decomposition of projects became the accepted model in the

decades that followed.

2:

This leads to another common characteristic that goes with the term

“waterfall” - rigid processes that tell everyone in detail what they

should do. Certainly the software process folks in the 90s were keen on

coming up with prescriptive methods, but such prescriptive thinking also

affected many who advocated iterative techniques. Indeed although agile

methods explicitly disavow this kind of Taylorist

thinking, I often hear of faux-agile

initiatives following this route.

3:

The notion that a phase should be finished before the next one is started

is a convenient fiction. Even the most eager waterfall

proponent would agree that some rework on prior stages is necessary in

practice, although I think most would say that if executed perfectly, each

activity wouldn't need rework. Royce's paper explicitly discussed how

iteration was expected between adjacent steps (eg Analysis and Program

Design in his figure). However Royce argued that longer backtracks (eg

between Program Design and Testing) were a serious problem.

4:

This does raise the question of whether there are contexts where

the waterfall style is actually better than the iterative one. In theory,

waterfall might well work better in situations where there was a deep

understanding of the requirements, and the technologies being used - and

neither of those things would significantly change during the life of the

product. I say "in theory" because I've not come across such a

circumstance, so I can't judge if waterfall would be appropriate in

practice. And even then I'd be reluctant to follow the waterfall style for

the later phases (code-test-integrate) as I've found so much value in

interleaving testing with coding while doing continuous integration..

5:

In the 90s it was generally accepted in the object-oriented world that

waterfall was a bad idea and should be replaced with an iterative style.

However I don't think there was the degree of embracing changing

requirements that appeared with the agile community.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to

Ben Noble, Clare Sudbury, David Johnston, Karl Brown, Kyle Hodgson, Pramod Sadalage, Prasanna Pendse, Rebecca Parsons, Sriram Narayan, Sriram Narayanan, Tiago Griffo, Unmesh Joshi, and Vidhyalakshmi

Narayanaswamy

who discussed drafts of this post on our internal

mailing list.

October 27, 2019

photostream 122

September 19, 2019

Using CD4ML to evolve without bias

Danilo, Arif and Christoph finish their article on Continuous Delivery

for Machine Learning with a peek at the future of platform thinking and

how we might use CD4ML to help evolve intelligent systems without bias.

September 18, 2019

Data Versioning and Pipelines in CD4ML

My colleagues continue their article on Continuous Delivery for Machine

Learning by looking at the future, considering what further work needs to

be done in Data Versioning and Data Pipelines.

September 11, 2019

Orchestration and Observability in CD4ML

Danilo, Arif and Christoph finish the technical components of

Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning with the last two items:

Continuous Delivery Orchestration, and Model Monitoring and Observability

September 9, 2019

Experiments Tracking and Model Deployment in CD4ML

The team tackles some more technical components of

Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning. This time they look at

Experiments Tracking and Model Deployment.

The actual cost of lock-in and how to reduce it

Gregor completes his article by totting up the total cost of avoiding

lock-in, and considering some examples of the decisions around lock-in.

September 6, 2019

Serving and testing models in CD4ML

My colleagues continue their discussion of the technical components of

Continuous Delivery for Machine Learning. This installment looks at model

serving, testing, and quality.

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1103 followers