Martin Fowler's Blog, page 11

April 29, 2020

Branching Patterns: Continuous Integration

Continuous Integration: Developers do mainline integration as soon as

they have a healthy commit they can share, usually less than a day's

work

April 28, 2020

Bliki: KeystoneInterface

Software development teams find life can be much easier if they integrate

their work as often as they can. They also find it valuable to release

frequently into production. But teams don't want to expose half-developed

features to their users. A useful technique to deal with this tension is to

build all the back-end code, integrate, but don't build the user-interface.

The feature can be integrated and tested, but the UI is held back until the

end until, like a keystone, it's added to complete the feature, revealing it

to the users.

A simple example of this technique might be to give a customer

the option of a rush order. Such an order needs to be priced, depending

on where the customer lives and what delivery companies operate there. The

nature of the goods involved affects the picking approach used

in the warehouse. Certain customers may qualify to have rush orders available

to them, which may also depend on the delivery location, the time of year, and

the kind of goods ordered.

All in all that's a fair bit of business logic, particularly since it will

involve gnarly integration with various warehousing, catalog, and customer

service systems. Doing this could take several weeks, while other features,

need to be released every few days. But as far as the user is concerned, a rush

order is just a check-box on the order form.

To build this using the check-box as the keystone, the team does

development work on the underlying business logic and interfaces to internal

systems over the course of several production releases. The user is unaware of

all this latent code. Only with the last step does the keystone check-box need

to be made visible, which can be done in a relatively short time. This way all

latent code can be integrated and be part of the system going into production,

reducing the problems that come with a long-lived feature branch.

The latent code does need to be tested to the same degree of

confidence that it would be if it were active. This can be done

providing the architecture of the system is setup so that most testing isn't

done through the user interface. Unit Tests

and other lower layers of the Test Pyramid should be easy to

run this way. Even Broad Stack Tests can be run

providing there is a mechanism to make them Subcutaneous Tests. In some cases there will a significant amount of behavior

within the UI itself, but this can also be tested if the

design allows the visible UI to be a Humble Object.

Not all applications are built in such a way that they can be extensively

tested in a subcutaneous manner - but the effort required to do this is

worthwhile even without the capability to use a keystone. Tests

running through the UI are always more trouble to setup, even with the best

tools to automate the process. Moving more tests to subcutaneous and lower

level tests, especially unit tests, can dramatically speed up Deployment Pipelines and enable Continuous Delivery.

Of course, most UIs will be more than a check-box, although often they

aren't that much more work to keystone. In a web app, a complex feature will often be an

independent web page, that can be built and tested in full, and the keystone is

merely a link. A desktop may have several screens where the keystone is the

menu-item to make them visible.

That said, there are cases when the UI can't be packaged into a simple

keystone. When that's the case then it's time to use Feature Toggles. Even in this case, however, thinking of a

keystone can be useful by ensuring that the feature toggle only applies to the

UI. This avoids scattering lots of toggle points through the back end code,

reduces the complexity of applying the toggle, allows the use of simple toggle mechanisms, and makes it easier to

remove when the time comes.

There is a general danger with developing a UI last, in that the back-end

code may be designed in a way that doesn't work with the UI once it's built,

or the UI isn't given the attention it needs until late, leading to a lack of

iteration and a poor user experience. For those reasons a keystone approach works best

within an overall approach that encourages building a product through thin

vertical slices that lead to releasing small but fully working features rapidly.

I've used the example of a user-interface here, but of course the same

approach can be used with any other interface, such as an API. By building the

consumer's interface last, and keeping it simple, we can build and integrate

even large features in small chunks.

Dark Launching is a variation where the new feature is called

once its built, but no results are shown to the user. This is done to

measure the impact on the back-end systems, which is useful for some changes.

Once all is good, we can add the keystone.

Acknowledgements

I first came across the metaphor of a keystone for this technique in the

second edition of Kent Beck's Extreme Programming

Explained . Pete Hodgson, Brandon Duff, and Stefan Smith

. Pete Hodgson, Brandon Duff, and Stefan Smith

reminded me that I'd forgotten this.

Dave Farley, Paul Hammant, and Pete Hodgson

commented on drafts on this post.

Branching Patterns: Integration Frequency

Integration Frequency has a huge impact upon a team's workflow. Higher

frequency integration reduces the problems of complex merges, makes

refactoring easier, and generally improves the communication and

cohesiveness of a team.

April 27, 2020

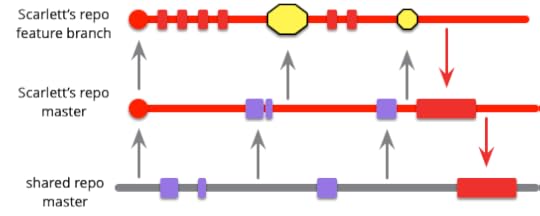

Branching Pattern: Feature Branching

April 23, 2020

Branching Pattern: Mainline Integration

Developers integrate their work by pulling from mainline, merging, and

- if healthy - pushing back into mainline

April 22, 2020

Branching Pattern: Healthy Branch

On each commit, perform automated checks, usually building and running

tests, to ensure there are no defects on the branch.

April 21, 2020

Branching Pattern: Mainline

The second branching pattern in my article is Mainline: a

single, shared, branch that acts as the current state of the product.

April 20, 2020

Patterns for Managing Source Code Branches

In my conversations with software developers, a regular topic of

controversy is how manage source code branching. Tools like git make it

easy to create branches, but managing them to improve coordination and

minimize the costs of integration unearths plenty of difficulties. I find

it useful to think of the trade-offs around branching as a series of

patterns, and have spent the last couple of months writing these patterns

into a coherent shape.

Today I'll start sharing these, with the foundation of thinking of

source branching as a pattern itself. An important point here is that the

conceptual notion of a branch is broader than what source code management

systems label as branches.

April 14, 2020

Refactoring: This class is too large

Most programmers have personal projects that do important things for

them personally, but never have enough time and energy to keep them in

good condition. Clare is no exception, and needed to spend time getting

such an unruly codebase back into line. Here she shares the first part of her

refactoring: breaking down a class that had become too big. It's a messy

situation, because that's what real refactoring is like - yet when done in a

controlled way, with lots of tiny steps, we can make real progress.

April 4, 2020

photostream 123

Martin Fowler's Blog

- Martin Fowler's profile

- 1102 followers