Sheenagh Pugh's Blog, page 9

October 16, 2022

Review of Venice: Discarded Daughter, by Marsha Fabio, pub. Newman Springs Publishing 2021

I do not write for applause, nor for prizes but rather to hold fast to my own natural talent and pleasure – Arcangela Tarabotti

I first came across unwilling 17th-century Venetian nun Arcangela Tarabotti in Mary Laven’s informative and entertaining account of Venetian convent life, Virgins of Venice. I knew this book would cover much of the same ground, particularly as regards the general background and history, but I wanted to find out more about Arcangela, in which I was not disappointed.

Arcangela was her conventual name; she was born Elena, to a middle-class family with more daughters than they could find dowries for. Dowries in Venice, despite the authorities’ efforts to regulate them, were ridiculously inflated. Hence the city’s enormous number of convents, which were basically storehouses for aristocratic and middle-class girls who had no hope of marriage – at one stage, 84% of the city’s 2.250 gentlewomen were in convents. Many of these girls, unsurprisingly, had no vocation for the enclosed religious life and had been coerced into it. Arcangela was lame, which made her less marriageable and a natural candidate for this fate.

Most of these girls reluctantly accepted what they could do little about. Many managed to find ways of circumventing the convent rules; a very few tried to physically escape. Arcangela is the only one I know of who, though she never supposed it possible or proper to retract her vows, protested bitterly and repeatedly, in writing, about what had happened to her. Patriarch Tiepolo, though genuinely sorry for these girls, could think of no alternative way of disposing of them. “But what would happen to 2,000 noble girls if they were not in the convent? What confusion! What harm! What disorder!” He clearly believed in the maxim aut maritus, aut murus: either a husband or a wall. Arcangela will have none of this; “Many authorities will have to repent closing their eyes in this way in the interests of the State, filling these horrible cloistered tombs with miserable and innocent women.”

Arcangela in fact became an author, and it is the greatest irony of her life that her enforced incarceration in the cloister not only inspired her career as a writer but made it possible. In the previous century, Cassandra Fedele had been, in her twenties, a renowned humanist scholar and epistolary writer, delivering public orations and taking part in debates with scholars at the University of Padua. But when, at 34, she married, her literary career came to an abrupt end and for the rest of her long life nothing was heard of her. Had Arcangela achieved the marriage she envied her sisters, the same would have happened to her.

Instead, her life focused on writing and getting her work published. This latter was difficult because of its controversial nature. Her first two books, L’inferno monacale (“The hell of monastic life”) and Tirannia paterna (“Paternal Tyranny”) pulled no punches, as may be inferred from their titles, and despite her best efforts she could not get them published in her lifetime. In other works, like Paradiso monacale, she toned down the subversiveness enough to get into print. Her Letters were also published; she corresponded with a wide range of scholars, writers and potential literary patrons. She was incredibly single-minded about her work, neither constant ill health nor the jealousy and spite of contemporary male writers could stop her. She was an autodidact; her handwriting was never good but she read widely and her mind seems to have been a hotbed of radical ideas.

One thing that irks me slightly about the style of this book is its habit of leaving certain words in Italian, in the middle of an English text. There is no indication that the work is translated from Italian, it seems to have been written in English – very well, in that case it’s “fourteenth-century”, not “Quattrocento”, and what is a phrase like “her dolente heartbeat” doing? There are also some instances of wrong word use, notably “flout” for “flaunt”, as in “Tarabotti faces detractors head-on, flouting her literary successes”. I found the style of Laven’s book more pleasing, but for Tarabotti’s life, this is undoubtedly where to go unless you can find Tarabotti’s own works at a less ruinous price than I have encountered. She was a remarkable person: bitter, angry, learned, driven, capable of humour and kindness, also of being totally unforgiving, notably toward her father. She knew her own worth but could be downright obsequious toward any patron she thought might get her published, and almost nothing could deter her from saying in print what she thought. As she once wrote, “when you’ve lost your freedom, what else is there left to lose?”

October 1, 2022

Review of A Pair of Three, by Claire Crowther, pub. Shearsman Books 2022

I wonder about the singularity

of a pair of three –

an us.

Claire Crowther has in the past sometimes been seen as, if not exactly a “difficult” or “obscure” poet, at least a determinedly cerebral one, not afraid to use vocabularies that don’t often feature in poetry (like that of physics in her collection Solar Cruise) and always demanding thought and concentration (amply repaid) from her reader. As we shall see, her technical and verbal skills are just as much in evidence here, but this collection’s focus is one that is perhaps more immediately accessible; the experience of being married to a person previously widowed. A marriage in which, pace the late Diana, there genuinely are three people:

It’s late. No, partner, not too late. Still

one of us is late: (A Pair of Three)

The pun on “late” is classic Crowther, as is the happy coinage “werhusband” in another poem. In “Case Endings” she uses the lexis of grammar to ponder this complicated relationship:

Could he/I/she be subjunctive?

wouldwife couldwife

Do ‘we’ have the present and/or the past?

triplecouple oncecouple doublecouple

Is every ending right?

wo/man wer/once

Can ‘I’ be objective about ‘them’…?

foundwife lostwife

Is this ending right for ‘us’…?

wefinders wekeepers

And in “The Physics of Coincidence” she uses line breaks to jolt the reader into thinking:

If two atoms

share an electron and bond in one body

in one compass-

ion of matter swaying with so much co-

incidence direct-

ionless as the atoms

But alongside this intellectual (though far from dispassionate) wordplay goes a far more direct and emotional response, for instance, in “Over”, to the sheer implausibility of death, the difficulty in believing that it can have impinged on ordinary life:

How could she lie so quiet

when she had mending to do?

How could he search for a vase

while she made him a widower?

And her technical ability never shows so clearly as when she expresses the feeling of another’s presence in that simplest-looking and most vernacular of all forms, the ballad. No form looks so easy to write; none is so easy to write badly. In “The Visitor”,

While he was out I read a book.

I had to rest that day.

Then I heard a key in the lock

and steps in the hallway

the tension begins with the pinpoint rhythms of those third and fourth lines and ratchets up throughout.

If this review begins to resemble a series of quotes, that is because it is very hard to express an idea in more telling words than those Crowther uses.

Must we all leave

down the line lyrical lying where we will? (Illyria by Rail).

“And what should I do in Illyria”, indeed… This is one of those collections that, because of the universality of its subject matter, speaks immediately to the reader. But at the same time, said reader recognises the presence of a powerful intellect and a depth of meaning that does not yield itself at a first reading.

September 16, 2022

Review of Rock-Bound by Jessie M.E. Saxby, pub Northus Shetland Classics 2022

“While restraining and checking in some things, as if I were a mere child, she sought to make me feel and act like a woman of mature years in other ways. For instance, when I wished to accompany Mrs Weir, her daughters and other families to a luncheon-party on board the war-vessel at that time stationed in our vicinity, she declined the invitation for me on the plea of my extreme youth; yet when I came downstairs by a succession of jumps from one flight of step to another, she reproved me for not showing the maidenly dignity which pertained to my years.”

Daughter’s place is in the wrong, in fact, and much of this early novel is concerned with a fractious mother/daughter relationship. Which in itself is sufficient explanation for Saxby’s irritation when reviewers at the time (1877), took it for partial autobiography, for while our heroine Inga’s mother is cold, unloving and self-obsessed, Jessie Saxby’s mother emphatically was not, and the author would not have wished that inference to be made. Nor was Saxby’s childhood isolated like Inga’s, for the high-achieving Edmondstons, her birth family, not only had many children (she was the ninth of eleven) but regularly entertained visitors from all over the kingdom and beyond. It is clear that Saxby, like all writers, used and transmuted elements of her own life – the grove of trees by Inga’s home is recognisably the plantation that so individualises Halligarth, Saxby’s childhood home, on otherwise almost treeless Unst. But there is a great difference between using material from one’s own life and “being one’s own heroine” as some obtuse critic apparently suggested was the case.

Though Jessie had written poems and stories from childhood and published her first story at 18, this is a first novel, and has some of the faults that might be expected. It revolves around three things: a child’s relationship with her absent father and all too present mother, a “love-triangle” and a mystery. The first two are skilfully handled; the drawing of character and relationships was clearly a strength of hers. The third, if one looks carefully at the plot, has more holes than a Shetland lace shawl, though I am bound to say that one does not notice the improbabilities much while caught up in the story, for she keeps up the narrative momentum well. Whether it would survive a second reading, without the tension of “what happens next” to distract one from questions, is another matter. Certainly the ending, with its convenient dead-of-the-fifth-act solutions for characters no longer needed and its echt-Victorian insistence that All Will Be Well If Only We Trust In God, is downright irritating – though Inga’s earlier attempt to cure herself of sorrow by means of doing good works in the neighbourhood is not; one can well believe such distraction would be therapeutic.

But the compensations are many. The characters are skilfully drawn and often engaging. Constantly-fainting Laurence, Inga’s cousin, is a wuss, but a believable one; Inga’s aloof mother, “The Lady”, a fascinating puzzle. The informal, bordering-on-rackety Weir family, who actually sound a lot more like the Edmondstons than Inga’s family does, are a delight. Their son Aytoun, though he does tend to patronise Inga a bit, is an easy man to fall in love with and his sisters’ conversation gives Saxby the chance to indulge some of her feminist leanings, as in Kate’s reaction to her older sister’s soppy behaviour when engaged:

“Oh, my dear,” cried Kate, “it is nothing to what I shall be when my turn comes. I shall not speak a word of fun or look a person in the face for months – not, in fact, until the chains are bound on me by the cruel hands of my ‘inflexible papa’. I shall scream off into hysterics whenever I am spoken to and swoon gracefully whenever the beloved object approaches. I shall indulge in weeping extensively, and sigh whenever I see the moon.”

This picture of tricksy, laughter-loving Kate was too much for me, and my mirth ran over as abundantly as even she liked to see. The mischievous maiden heaved a comic sigh and proceeded – “I do trust the fever will go straight through the house in the order of our ages. There is the prospect that it may do so, having begun at the eldest, for in that case I shall have respite until Lily and Aytoun are comfortably married and done for.”

Saxby’s own marriage had been a love-match, and a happy one, but when it was ended by her husband’s early death, she managed to support her five sons by her writing. She did not remarry, and one gets the impression that while she had nothing against marriage, she could be as happy living independently. The initial E in her name stands for Edmondston, her birth-name, and it would seem that at heart she was always a member of that brilliant clan, for though she lived many years in Edinburgh she eventually moved back to Unst, the island of her childhood. Vaalafiel, Inga’s island in the novel, is not identical with Saxby’s Unst, but many of their geographical features are alike, and in an odd way, the very absence of much “place description” in the novel is testimony to how ingrained the landscape was in her, so much so that it seldom occurred to her to remark on it. (It is also true, I think, that human beings simply interested her more than landscape.) But her brief pen-portrait of the island, early in the novel, is a fine example of place description doing more than appears on the surface, in this case imparting an air of quiet, concealed menace to the proceedings:

“If you were an eagle, among your hereditary clouds, and looked down upon Vaalafiel, you would see that it is coiled up on the sea much in the way a kitten rolls itself together on the hearthrug – the creature’s paws being represented by the narrow belts of land overlapping each other and forming the arms of our Voe (fjord), whose crags are very suggestive of claws!”

The virtues of this novel are in its sharp observation of character and relationships and a certain dry humour which Inga shares with her creator and which, for most of the time, greatly enlivens the narrative.

September 1, 2022

Review of Dutch Light by Hugh Aldersey Williams, pub. Picador 2020

This is subtitled “Christiaan Huygens and the Making of Science in Europe”; it would not be wholly accurate to call it a biography of Huygens since his father Constantiyn takes up nearly as much of the book. The two were similar in talent but differed in their ways of exercising it. Constantiyn was an amateur in the best sense, a man of wide interests both scientific and artistic, a musician and poet who also had a bent for architecture and design. Christiaan, though he too had musical and artistic interests, was far more of a specialist, a genuine “scientist”, though the term was not then common, who was particularly fascinated by astronomy, optics and everything to do with the nature and movement of light.

Unsurprisingly, Constantiyn is the more engaging and interesting personality – people of wide interests are usually more entertaining than specialists – but Christiaan’s work and way of thinking are themselves fascinating. Williams is concerned to rectify the lack of notice from which his subject suffers in comparison with his contemporary Isaac Newton. In their day, they were seen as equals, which seems reasonable when you consider that Christiaan was the first to identify the rings of Saturn, figured out that light moves in waves (unlike Newton) and, in rejecting the idea that motion was absolute rather than relative to its surroundings, came very close, as Einstein recognised, to a theory of relativity in general.

The title alludes to the interesting likeness between Dutch art and science in prioritising the nature of light. Williams speculates not altogether seriously on whether there really was a particular form of ambient light in the Netherlands and concludes not, but I do wonder whether the “big sky” one finds in a flat country helped it produce more than its fair share of astronomers. What certainly must have helped were the Dutch advances in lens-grinding, a job which scholars experimenting with new and better devices for seeing the world did not disdain to do for themselves – Huygens and his brother ground their own lenses, when they did not use those being turned out by the equally skilled practitioner Spinoza, who made a living from lens-grinding when not philosophizing.

Several other big names turn up in bit parts in this story – Cassini, forever finding new moons, Rembrandt, a protégé of Christiaan’s father Constantiyn, the unfortunate de Witt brothers for whom politics went so horribly and terminally wrong. One of the most interesting to me was Henry Oldenburg, born Heinrich, one of the founder members of the Royal Society and an internationalist who spent a lot of his time keeping scientists in various countries in contact with each other, helping them acquire what they needed for research, nudging them to get their work published and patching up the quarrels that inevitably arose between ambitious men touchy about who discovered what and when. I knew him from another recent book which focuses on his role in keeping the Society firmly sceptical about pseudo-sciences like astrology, but his role as facilitator-general is even more admirable.

The book, like the lives of Christiaan and his family, moves between Holland, Paris and London, and its picture of Dutch life at the time - questioning, tolerant, civilised (who knew there was a canal-based public transport system between the main towns?) - is as interesting as any of its portraits of individuals. It is generously illustrated, with copious notes and index. In the description of Christiaan’s death, what is said about his unorthodox religious views made me want to learn more of them, but since they seem to have come as something of a shock to his own family, perhaps not much more is known (he seems to have felt that immortality consisted only of what we leave behind us).

I was glad to have learned more, not only about Huygens father and son, but about the place and the fascinating period of history in which they lived.

August 15, 2022

Review of The Decline of Magic, by Michael Hunter, pub. Yale University Press 2020

In 1685, John Edwards, a divine, asserted that “the denial of Daemons and Witches” was “an open defiance to unquestionable History”. In 1749, another divine, Conyers Middleton, declared that “the belief in witches is now utterly extinct and quietly buried without involving history in its ruin”. Neither man was particularly out of step with his time, and in just over 60 years this was a very considerable turnaround in educated opinion. This book examines how belief in supernatural phenomena like witches, fairies, second sight, prophecy and ghosts became discredited among intellectuals, if not always, or even at all, in popular culture.

This has often been attributed mainly to the rise in science, and clearly the scientific habits of demanding evidence, extrapolating from known facts and evaluating sources had a lot to do with it. As John Wagstaffe (who was out of step with his time) tartly observed in The Question of Witchcraft Debated (1669), "It is far more easy, and more rational, to believe that witnesses are liars and perjured persons, than it is to believe that an old woman can turn herself or any body else into a cat". Hunter examines the role of the Royal Society in the matter and shows that while some individual members of the Society took stances on both sides of the question, the Society as a corporate body stayed well out of it, hardly ever debating anything with a “magic” tinge, like astrology or “miraculous” cures, even when individual members occasionally suggested they be investigated. Though they never said so, the implication is that the Society considered such matters beneath them and no part of their scientific remit, and this sidelining in itself “helped to relegate such investigations to the realm of pseudo-science”. In 1698 a meeting of the Society had discussed second sight; by the 1740s, a Fellow interested in the phenomenon makes it clear in correspondence that this is a private concern “which could not be brought before us as a Society not coming within the design of our Institution”. It’s interesting to consider that attitudes may change because something is not discussed as much as because it is.

One fascinating line Hunter pursues is the role of manuscript sources, like notebooks and letters, and coffee-house oral culture in spreading ideas for which it was not always easy to find a print publisher, since sceptics on such matters tended to be accused of being atheists. Clearly the coffee-house “scoffers” were widely resented, not just for their unorthodox views but for the caustic wit with which they expressed them. Indeed, reading diatribes like Glanville’s “quibblers and buffoons that have some little scraps of learning matcht with a great proportion of confidence” or the “Town-wit” described in a 1673 pamphlet, “speak of Spirits and he tells you he knows none better than those of wine; name but Immaterial Essence and he shall flout at you as a dull Fop incapable of sense”, one cannot help thinking of the resentment of our own tabloids against “experts” and “woke” intellectuals. It is also interesting to see how, the more “magic” was discredited in the intellectual world, the more of a role it began to play in fiction (Scott, who was happy to use “magical” elements like ghosts and second sight in his writing, had no time at all for such superstitions in real life).

In the written arguments of the two sides, one sees, over and over, contempt on the side of the sceptics and furious resentment on the part of their opponents. This had a predictable effect on debate, as Hunter notes in his conclusions on the debate between Wagstaffe and his opponents Casaubon and “RT”:

“It is almost as if intellectual change does not really occur through argument at all; that the detailed debates that we reconstruct from erudite tomes might as well never have happened. People just made up their minds and then grasped at arguments to substantiate their preconceived ideas, with a new generation simply rejecting out of hand the commonplaces of the old.”

This resonates in a modern context, for the gap between scepticism and credulity is surely still as wide as ever in the popular consciousness, however much credulity has been discredited in the intellectual community. Not many, at least in the West, now believe in witches and demons, but plenty still credit ghosts, astrology, alien invasions by little green men (or lizards), injections in the arm that somehow deliver microchips to the brain, and much else that makes mediaeval witchfinders look positively rational. And you can’t argue them out of it; try it and see how far you get. I still recall the response of a woman on Twitter to someone who had proved, beyond all possibility of argument, that she was wrong about something: “Stop trying to bully me with facts; I’ll stick to my own opinion”. John Wagstaffe must have met someone like her, when he wrote: "This is palpable enough, that when the best of our understanding is inclined to any party by the strong biases of education and interest, we straightway greedily embrace all shows and appearances of reason, which seem to make for our side, and with abundance of self-applause, improve a mere sneaking hint of an opinion into a demonstrative confidence."

One thing I certainly hadn’t appreciated, before reading this, was how closely, to a 17th-century mind, belief in “magic” of various kinds was bound up with religion, and how sure they were that disbelief in witchcraft, ghosts etc would lead to atheism. Edwards asserted in 1695 that “it is plain the rejecting of the commerce of Daemons or Infernal Spirits opens a door to the denial of the Deity, of which we can no otherwise conceive than that it is an Eternal Spirit”. He was right, of course, denial of the Deity is indeed the logical conclusion of scepticism about the spirit world, but being of his time, he could not allow himself to wonder if that might be a good idea.

This is a proper history, with all the necessary apparatus of notes and index, but very readable. The first, introductory, chapter, in which he is surveying previous authors in the field and setting out his stall, is the densest read, but necessary and well worth it to get to the rest.

August 1, 2022

Review of The Last House by R G Adams, pub. Quercus Books 2022

“As she pushed through the swing doors, the noise level hit her ears so hard that she flinched. Rows of social workers wearing headsets were taking call after call from anxious, desperate people and attempting to re-route them to overloaded teams. The buzz of it was electric; she’d thought about applying to work in the team herself when she’d finished uni. But the repeated sifting and passing on of referrals would have driven her nuts, not being able to work with families properly, never following anything through. It was a job that clocked up a lot of brownie points if you could hack it, though, not least because one tiny mistake could mean something catastrophic happening to a child.”

Kit Goddard, South Wales social worker specialising in child protection and the protagonist of R G Adams’ novel Allegation, reviewed here, is back on another case. Think police procedural, only for “detective” read “social worker”. As you can see from the above, the author writes with the assurance of one well acquainted with the milieu in question and brings it convincingly alive as she did in the first of these books.

Kit is still terrier-like at her job, harassed by her dysfunctional family and has an entertaining line in observational cattiness: “Sisters, Kit reckoned, and they were clearly unnaturally close, because they’d recently shared a shade of Nice’n Easy that was way too harsh for both of them”. At the start of this novel, she is missing her former boss Vernon, off work with the minor heart attack he suffered near the end of Allegation, and replaced by Georgia, who has neither his dedication to the job nor his disregard for red tape. Georgia and the head of the mental health section, Tim, are both eager to close a case involving a teenage boy and his mother living in isolation; Kit is sure they should not and pursues answers on her own. For obvious reasons, I’ll avoid saying too much more about the plot.

The physical setting, in the valleys and seaside towns of South Wales, is handled with as much assurance as the social work scene. The echoes of the miners’ strike and the Italian influence in the area never sound contrived or dropped in for effect, and the local dialect, (as I can promise you, having lived there many years) rings true: Mal’s ‘You need to think twice by here, Gio’ is dead right. Indeed the dialect throughout is both lively and convincing:

‘You know that thing about you can’t miss what you never had?’

‘Yeah?’

‘That’s bollocks, then.’

‘Seems it must be. You miss the hope of having it one day, I guess.’

‘That’s deep, that is. You could get that put on a tattoo.’

‘Shut up.’

Of course, the main requirement for a novel like this (is there a word for a police-procedural where the protagonists aren’t actually police?) is that it should be a page-turner, giving enough clues to the solution but not too many, and maintaining both the tension and the reader’s anxiety to know what happens next. Since I read it in an afternoon and only a couple of sittings, I should say the answer was a resounding yes. Nor is it essential to have read the earlier book, though I can certainly recommend it; this is a standalone, albeit with several of the same characters. Though for all the satisfaction of solving mysteries and meeting again some engaging and believable characters, I think what I like most about these books is the laconic voice the author shares with her protagonist, as when Kit is mentally translating an address out of Welsh: ‘So, it was Last House, High Rock, Long Valley. And under the Cold Mountain, to boot. Perhaps the council had named the street ‘Sunnyside’ in an attempt to cheer the residents up.’

July 16, 2022

Review of “Rock Bird, Butterfly” and “Old Friends”, by Hannah Lowe, pub. Hercules Editions 2022

Hercules, of course, specialises in small jewel-like collaborations between poetry and art. Here we have two little books of poems by Hannah Lowe, both dealing with her Chinese heritage. Old Friends explores the present and past of Limehouse and some of the real and fictional Chinese characters associated with it, while Rock, Bird, Butterfly looks at the Western concept of chinoiserie via the medium of Chinese wallpaper, beautifully illustrated in the book, which also contains a very informative foreword by Clare Taylor and an afterword by the poet. Old Friends is illustrated with photographs and paintings and contains a foreword by Anna Chen and a conversation with Richard Scott.

The subject matter of both collections is intrinsically interesting, while the poet’s style is lively and often has an engaging humour. Rock, Bird, Butterfly is by its nature ekphrastic – each poem is inspired by a different wallpaper - and I don’t think it always avoids the great danger of ekphrastic poetry, namely doing no more than explain what the art has already made clear. Ideally the poem should give one a different slant on the image, and sometimes it does, as when, in “Travel Papers”, she traces the story of an iconic paper through various extremely wealthy Western hands:

who acquired it from the house of an oilman

in Palm Beach, Florida, who bought the house

from Mona von Bismarck, millionaire

and ‘best dressed woman in America’

who in Cecil Beaton’s watercolour

sits with her husband Eddie

and their dog on a Syrie Maugham sofa

back to its origin:

and must, the experts think, have been made

at the same painting workshop,

somewhere in Guangzhou, three hundred years ago.

Sometimes, though, the combination of the illustration with the scholarly and fascinating foreword risks telling us all we need to know before the actual poem gets started. Nevertheless, the little narratives are full of interest and the illustrations quite ravishing, so much so that for once, it is the images that make most impact on me.

In Old Friends, words and images are more on an equality and indeed more independent of each other. I cannot imagine Rock, Bird, Butterfly without the illustrations. I can see the poems of Old Friends standing alone, which is in no way to imply that the images don’t earn their place and add interest. In the last poem, “Hauntology”, a Blue Funnel Line advertising poster showing a steamship and flying birds (geese, I think but I’m no ornithologist) sparks a poem about the back-story of the narrator’s grandfather and father. The poem begins

I see my grandfather – he’s sailing

on a paper ship. He is old but young

and ends

He taught him how to make a paper bird.

It flew away, came back, and made these words.

Here, the way the “paper ship” and bird of the poster turn into memories of those the grandfather made and finally into words on paper seems to me a most effective re-imagining of the image. Another interesting poem in this booklet is “The Oral Historians”, focusing wryly on how hard it is to form an accurate picture of the past from the memories of those who lived it (not for nothing do policemen say there’s no one less reliable than an eyewitness). In another, untitled, poem she again manages to make a very believable link between a present moment and a rich, long-gone past:

The splosh

of soup on blue-vine china brings back my father,

and lets me hear the lapping of the river,

hauling in its cargo. Porcelain and tea,

the rolls of Chinese wallpaper, bananas,

rum, molasses, resin, ivory,

Persian rugs and spice and ostrich feathers

filled the old brick warehouses

It will be clear by now that she works a lot in form and handles it deftly.

I have reviewed several Hercules books now, and they have all been immaculately produced. I was surprised, therefore, to find quite a few typos in these two, some in the afterword to Rock, Bird, Butterfly but some, more unfortunately, in the poems, in both booklets. In the first line of “If the Wallpaper Could Speak”, we have “Would anyone listen its tales”, rather than “listen to”; in “The Curator” there are two instances of “bought” for “brought”; in the last two lines of “The Ducks”, it looks as if “ducks waddle,/peddling through your mind” should have been “pedalling”, though I suppose they might have been travelling-salesducks. In poem 5 of Old Friends, “The hang across the ceiling” must, from the context, be meant to be “they hang”; in “The Oral Historians” there seems to be a word (“are”?) missing from the complete sentence “They wonder if these things in her head” and in these lines from “Broken Blossoms”, “the Chinese man who loves her – his battered, plum-mouthed cherubim”, the last word should be “cherub” (cherubim is the plural and it’s clearly the singular we need here). That last might perhaps be the poet’s error rather than a typo, but editing should still have picked it up. Typos are undesirable anywhere, but more so in a production where appearance counts for so much.

I hope this criticism does not sound nit-picking; the poems are worth reading and the images range from interesting to stunning. But Hercules books are such beautiful little artefacts, one doesn’t want anything to detract from them.

July 1, 2022

Review of Feeling Unusual, by Ann Drysdale, pub. Shoestring Press 2022

They were the doors out of the ordinary

(“Mari Lwyd Finds the Forgotten Horses”)

There’s a kind of poem, much beloved of our present Laureate and others, which begins in the real world and then at some point veers off into the realms of fantasy, like Corporal Jones. It is not a mode I recall Ann Drysdale using much in the past, but here the very second poem, “Setting Off”, is one such: at the start the speaker seems to be a perfectly ordinary person, getting on in years, out for a bike ride. Indeed the first lines are achingly realistic about the laboured movements of age:

I cock my leg stiffly over the saddle

and settle my behind roughly amidships.

But by the time we go “through the closed gate” “unseen”, it is clear that the journey is now taking place elsewhere than in the real world:

Having no brakes, I fly on through the brambles

where nature’s creatures go about their business.

If I had wheels, I’d crash into the wall.

There is an awareness of age throughout the collection, in the crafting of walking sticks, the appalled realisation that one’s neighbours see one as old, the passing of time that blurs memories:

History happens at the moment when

Where are they now? becomes Where were they then?

Perhaps the most poignant reference to age comes in “Kiftsgate”, in which a rampant rambling rose (R filipes Kiftsgate, a tough blighter) fights back while being pruned:

You find unguarded skin above my gloves

lifting it deftly with your wicked fingers

so that I flinch and yelp and tweak it free,

watching it settle slowly back in place

over my old flesh like a wrinkled stocking.

This is typical of her sharp, unflinching observation of little things; the time it takes aging skin, once pinched, to settle back into place would strike a chord with anyone over a certain age. It is also typical of her irrepressible humour; she knows very well that “wrinkled stocking”, for many, will evoke Nora Batty, and that’s fine. There is humour too in her awareness of covid, but also darkness, because these poems focus on the resulting social isolation, perhaps of someone shielding. “Boat” begins wryly:

I open my own front door with my elbow;

in time of plague this is considered best

But by the time metaphor has again taken us partway into the realm of fantasy, the tone has darkened:

I know where I am now; I’m in a boat.

The narrow street outside is a towpath

and all the passers-by, a scant six feet

from where I watch them through my grubby portholes,

are either good folk out for exercise

or rough mechanicals about their business

and, while aboard, I shall remain in safety

until they, and the pestilence, have passed.

Another covid-related poem (“Fencing”) evokes the fear of contact in fencing terminology, turning a street conversation into a duel, and in “Sommerreise” the speaker even finds consolation in the fact that her “lost dog and last lover” are “dead and out of danger”.

“Clearing the Decks”, a sequence of two poems about disposing of unwanted stuff, reflects the ecological concern that is more and more evident in contemporary poetry but which, in this collection, also hints at the increased consciousness of transience in those who are themselves getting older. The next poem, “Stones with Sad Faces” belongs to these poems too, in a way, being about things which have been taken as souvenirs from the place where they really belonged.

This, then, is in some ways an elegiac collection, but with a lot of incidental humour and energy. The latter is particularly apparent in the “Mari Lwyd” poems scattered through the collection. Mari, the original Welsh “stick with an ‘orse’s ‘ead ‘andle”, except that the head was a real equine skull, was traditionally carried round the neighbourhood at Christmas seeking hospitality at houses to the accompaniment of song. Here Mari becomes, as the acknowledgements page states, a sort of “imaginary friend”, calling back memories of a young girl’s fascination with horses fictional and real, of overburdened work-horses and the horses of myth. In “Mari Lwyd Will Be Coming Soon”, the theme of letting go, already touched on, returns; a tableful of bone china, inherited and long preserved, is deliberately destroyed in a way that makes it clear what the Mari outside means, at least to this host:

All her skills

have hitherto been honed for acquisition [...]

followed by years of care and conservation.

It is as she envisaged. One great fall

Outside there is a new silence. Inside

there is the crunch of eggshells underfoot

as she opens the door to the pale horse.

June 14, 2022

Review of "As If To Sing" by Paul Henry, pub. Seren 2022

Tut-tut

says the metronome

Two words I’ve used before in reviews of Henry’s work, “fugue” and “elegiac”, are becoming ever more appropriate. He has always used recurring themes and images in a fugue-like way, and the more he does it, the more they resonate. And of course, the more life one has to look back on, the more elegiac one’s poems are liable to become. Certainly this collection is pervaded by a sense not just of time passing but of mortality.

The collection is in three parts. The first, As If To Sing, is indeed very music-centred, and though the wider world makes an appearance in poems like “Tauseef Akhtar’s Harmonium” and the title poem, which references the Great War, this section is mostly haunted by the poet’s own past. It contains “The Well of Song”, in which the poet, listening to a woman’s voice (very possibly his mother’s) on a gramophone record, observes

The needle works towards

the hole time slips through.

Even more conscious of the passing of time is “Last Move”, with its image, like a dream or fantasy, of lost parents:

It is too cold to stop and talk.

Their mournful steps leave no prints.

My mother smiles at my greying hair,

half-raises a gloved hand.

Songs hibernate inside her.

We may not pass like this again.

The effectiveness with which he uses heavily end-stopped lines here is typical of this collection’s concern for technique. There is a line in the second section:

Your cot a tight fit in the white Fiat (“The New Tenant”)

which is a positive Persian carpet of sound patterns and might, at first sight, look like a tongue-twister – but say it out loud and it flows musically off the tongue without a hitch. Part of it is his feeling for rhythm, which is faultless and much to the fore in a couple of ballad-style poems from the second section, “The Boys in the Branches”:

Your weekly gift, these minutes

alone, that pass into years,

a small park’s blinding light,

and you not waiting there. (“The Winter Park”)

As usual, though, you have to look for the technique; it doesn’t advertise itself like that of some poets who like to leave the scaffolding up. Henry tends to make it look easy, though if you try to emulate him, you will soon find it isn’t. Phrase after phrase, in his poems, sounds right, without it being all that obvious why:

a flock of cellos settled

on the saltmarsh

and remembered us

to the sea’s applause (Cave Songs)

or the end of his Mari Llwyd poem for New Year:

and the bells in the valley hold their tongues

and the ghostly snow horses thaw

and the mice bed down in the walls. (Dust o’clock)

He seems, in this collection, to be getting ever more spare in his utterance: Catrin Sands, a figure familiar from earlier collections, is “Cat” here, and the contraction feels appropriate in a collection where passing allusions like “three conifers” recall whole poems from elsewhere. In fact, if you are new to Henry’s work, don’t begin with this one, because many motifs, images, even individual words, in it will resonate more if you already know them from his earlier work. If on the other hand you are already acquainted with Penllain, Brown Helen, three trees, a haircut, Newport and many other old friends, go ahead and enjoy both the craftsmanship and the nostalgia. Its final poem in English (there is a brief coda in Welsh) is “Cei Newydd”, which brings us back to mortality:

We drifted out one afternoon

on a dinghy’s water-bed,

woke to no sight of the shore.

We had not been born.

A panic of oars

scratched the wilderness

and the harbour came back to us,

our mothers on the pier.

The salt on the fishing nets

tasted the same.

Soon, Brown Helen,

we shall drift out again.

June 1, 2022

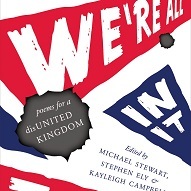

Review of We’re All In It Together, eds Michael Stewart, Steve Ely, Kayleigh Campbell, Grist 2022

This is an anthology of “poems for a disUnited Kingdom”, with a “state-of-the-nation” focus, as the preface calls it. The call for poems, which we’ll return to later, asked “What does it mean to be ‘British’ […] Is it possible for the Kingdom to become United? Is it even desirable?”

This remit, for all the exhortation “interpret the brief in your own way”, was clearly always going to produce highly politicised, even polemical, poetry. Whether this works depends a lot on whether the poet can come at the theme somewhat slant, creep up behind the reader with a rapier rather than charging head-on with a club. The very first poem, Jim Greenhalf’s “Imperial Exodus”, had me exclaiming out loud with admiration at its subtlety and artfulness in this regard. It is a two-parter about the end of an empire, one part in the voice of the subjugated natives soon to be free, the other in that of one of the imperialists going home. But where is “home”? Clearly, it’s Rome, and the liberated natives are British:

Did you see it, the last boat leaving?

Thank God they’ve gone. Good riddance.

All these years they’ve been telling us

what to do and how they want it done.

Things can only get better now, they say.

No more Pax this and Pax that.”

Or is it?

And they called us barbarians!

They treated us as refugees in our own country,

changing our habits, our customs, words

The point of course is that be they Roman, British, or what you will, empires are much the same everywhere. The second voice, gloomily contemplating a return to a place which he knows is not the “home” of his imagination, if it ever was, almost certainly did once belong to some Roman centurion, and also to some hidebound British administrator nostalgic for Fifties Britain and dreading a return to its modern incarnation:

I’m sorry to be going back.

Nothing glorious in that old ruin

of slaves and foreigners

pouring like floodwater over our borders.

This poem was a terrific start to an anthology, respecting the reader’s intelligence, feeling its way into the minds of its narrators and not preaching at us. Another that impressed me greatly was Gerry Cambridge’s “The Green and the Blue”, in which our narrator must find a way of living alongside the Neighbour from Hell, aka the Glasgow Rangers fan in the downstairs flat. It isn’t just that on match days the music is ear-splitting, it’s the question, in the narrator’s mind, of motive. Is the volume accidental or deliberately aimed at him as a Catholic? Face to face, the neighbour doesn’t seem as intimidating as the narrator feared:

An uncertain

broken-toothed smile. Skinny as a whippet, late twenties

Yet even his apparent co-operation about the noise raises suspicions about motive:

Next time it’s too loud

jist come doon an chap on the door. I understand

this puts the onus back on me by apparent sleight of hand –

Unconscious, or sleekit ruse?

The dance of approach and retreat, reaching out and suspicion, between these two is deftly done and rather moving. It’s also, as far as I can see, deeply pessimistic. I see no way for these neighbours ever to be part of a “united” society; too much divides them and religion is actually the least of it.

Division indeed is the keynote of the anthology. Rosie Garland and Mia Rayson Regan focus on the isolation caused by covid. Others highlight the divisions of Brexit. Many centre on race, from Aamina Khan’s “Yorkshire Cricket” to Ben Banyard’s “Scottish Tenner”, a far smaller incident but almost as redolent of distrust and suspicion as “The Green and the Blue”. Sexual politics and divisions, though not altogether absent, figure less, perhaps because only about a fifth of submitted poems came from women. Meanwhile Georgia Hilton likens England, in “Oh England I Love You”, to an “ageing parent”, right-wing and xenophobic, who constantly falls for well-spoken con men. It probably seemed like a good analogy for the way electors vote against their own interests; the trouble is, it relies on an offensively ageist stereotype. Believe it or not, the elderly are not all, or even mostly, gullible far-right bigots, and if we’re accusing people of having “fallen into the black hole/of internet conspiracy theories”, I seem to come across people of all ages who do that. The way government has managed to set different sectors of the community – young and old, black and white, gay and straight - against each other to distract them from the common enemy, ie those who have the money and power and are determined to hold on to it, would have made a good poem for this anthology, but this one just feeds into the prevailing narrative.

Many will probably feel angered and alienated by one or more poems in this anthology, since alienation is at the heart of it. There is certainly plenty of energy and commitment, though humour is in short supply, an exception being William Thirsk Gaskill’s wry sideswipe at bureaucracy, “On This Occasion”. The preface mentions that many poems were rejected for being “too hectoring and didactic”. I think a few still got through. Indeed, reading the text of the open call quoted in the preface, I don’t think I have ever seen quite so many abstract nouns in one paragraph, and if I’d read the call at the time, I would certainly have assumed they wanted poems about isms and ologies rather than people. Fortunately, they didn’t always get them. A few here do strike me as too obvious, and there are a couple whose point eludes me. But the good considerably outweighs the bad, which is most of what you can ask of an anthology.

The other thing you can ask is that it fulfils whatever remit it has set itself, and I think it does, in an odd sort of way. Though covid does figure, the acrimonious division that emerged between mask-wearers and anti-maskers does not, and nor does the way this division seamlessly followed on from that of Brexit. Whichever Twitter bubble one is in, the Venn diagrams for Remainers/mask-wearers and Brexiters/covid-deniers are almost perfect circles (and I did say “almost”, so don’t bother telling me if you’re the exception). This would lead me to suppose that the natural state of this, and perhaps any, country, is tribalism rather than unity, maybe because most countries are too big to be tribes in themselves, and that people will seize on anything to argue about just for the feeling of being in one tribe and against another. The poem which best encapsulates this tribalism is Gerry Cambridge’s, but the sheer variety of divisions represented here, not to mention the seeming triviality of some of them, itself, I think, answers the question in the preface, “Is it possible for the Kingdom to become United?” Doesn’t look like it.