Sheenagh Pugh's Blog, page 5

April 1, 2024

Review of The Yellow Nineties, by Catherine Fisher, pub. Three Impostors 2024

What happens to us when we enter a story?

Where do we go?

How is time stopped?

A long short story about reading a novella… can that work? Well, yes, it can, because stories are all about the way you tell ‘em, and this one, mirroring the techniques of its model, offers a series of nested narrations and interlinked mysteries that echo the “Chinese boxes” to which the original author compared his tale.

A young man-about-town in 1894 – an unidentified “you”, for the tale is told in the second person and the reader encouraged to identify with him – is leafing through the newspaper in a café (“The Empire seems in good shape – Matabeleland has just been occupied”). His eye falls on a review of a book just published:

“The book is an incoherent nightmare of sex and the supposed horrible mysteries behind it, such as might conceivably possess a man given to a morbid brooding over these matters, but which would soon lead to insanity if unrestrained.”

Naturally attracted, our protagonist rushes off to buy the book: Arthur Machen’s The Great God Pan. He is not disappointed; reading in front of the fire he is soon hypnotised first by Machen’s place-description, creating the countryside of the Welsh Border, then by the strange tale of the girl who sees Pan. Pausing to stoke the fire, he begins to muse:

“Of course, Pan is everywhere and, as yet unbeknownst to you, will be extremely fashionable for the next twenty years or so. He is stalking the cities and woods and libraries of Britain, half-man, half-goat, a hybrid being, lord of animals, bringer of madness. He has perhaps come back out of curiosity, because surely there is nowhere further from his sylvan glades than the dark streets of Pimlico and Soho?

And yet his devotees move among the throngs of London.

Fauns, naiads, dryads, centaurs. The architecture of the city is rich with carvings, gargoyles, herms. All these huge new self-important buildings, these offices, museums, department stores are infiltrated by their mocking or spying faces. How often have you glanced up and seen against the sky some secret sphinx or solemn caryatid?”

The young man reads to the end of the book, “tea going cold, the butter congealing, the fire forgotten”. He knows that if he discusses it with his friends later, he will dismiss it as “overheated. Sensational. […] hardly literature”. Fisher is an admirer of Machen and in the paragraph that follows, her own authorial stance comes over very clearly:

“Such books as this are not in the world of literary awards and prizes, of fine criticism, of high-souled and earnest discussion […] Such books and those who write them are not lofty or enlightening, they do not raise the soul.

In fact they take you down. Down into the deepest layers of the psyche, into dread, into fear, into the things that are so terrible they can only be hinted at.

Into Pan’s world of mischief and joy and panic.

Is that not also part of the human experience?”

Our young man later runs into Machen himself in a pub, not entirely by accident, and so do we in the sense that his preface to the 1916 edition of The Great God Pan is appended to this story. Machen is very interesting on how the landscape in which he grew up inspired the novella, and indeed on his ways of working in general: “I had acquired that ill habit of writing, that queer itch which so works that the patient if he be neither writing nor thinking of something to be written is bored and dull and unhappy. So I wrote”.

The publisher Three Impostors Press is a Newport firm specialising in “producing high quality, scholarly versions of interesting, rare and out-of-print books, along with other related new writing”, and as their name implies, their first projects were all connected with Arthur Machen. The series London Adventures, of which this is one, are individual short stories having some connection with London and produced in limited numbered editions of 250 for £10 each, which doesn’t seem a lot in the circumstances. There are three so far. If you’d like to lay hands on The Yellow Nineties , Iain Sinclair's House of Flies or Xiaolu Gu’s Alice of London Fields, I recommend no delay. I can testify that The Yellow Nineties fulfilled its intended purpose in that, having previously had no special desire to read Machen, I went off to Gutenberg’s handy online resource and read The Great God Pan.

March 16, 2024

Review of The Electron-Ghost Casino by Randolph Healy, pub. Miami University Press 2024

“Without lacunae a ladder is just a plank” ("DU BOUT DE LA PENSEÉ")

The Electron-Ghost Casino has a preface, unusual in a poetry collection, which tells us:

“The title, “The Electron-Ghost Casino” refers to Rutherford’s gold foil experiment of 1911 showing that atoms are mainly empty space. If you took away the empty space, the entire population of the earth would fit in a teaspoon. Of course, you wouldn’t be able to lift it. (I should credit a student of mine, Logan Duff, who asked “Are we all then just electron ghosts?” when we were covering the topic.) The appearance of solidity when Samuel Johnson kicked a stone in a bid to refute immaterialism was due to his electron fields repelling those of the stone. The casino bit is a gloss on evolutionary processes, where most trials end in failure.”

I take this to mean, in non-technical terms, that life is chancy and that world is not only more various but less solid than we think. But it also demonstrates Healy’s background, again unusual for a poet, in maths and science. He uses vocabulary and concepts from these fields very familiarly, and not just in humorous squibs like

When the sun hits your eye

like the square root of pi

that’s statistics

(“Hold Your Breath For Global Warming”).

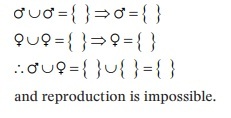

“Null Sex Lemma (for Walter Benjamin)” goes, in full:

I haven’t a hope of understanding that, so I can’t tell if it too is humorously intended. He certainly is a poet of a wry humour, as witness “Carbon Footprints”, where his father, an unwilling DIY-er, constructs a child’s bed:

Each night when I made my bed

I thought of him

sometime around 3 a.m.

when it collapsed again

I love this for its satirical take on the dutiful “family” poem prized by some editors, and indeed readers, which generally ends in a gush of sentiment about the late parent. I also liked “Hall of Near Fame”, with its tweaking of pop groups’ names that wasn’t quite as flippant as it looked:

Steely Din

The Righteous Bothers

The Polite

Sadness

The Gee Gees

When, in “The Road To God Knows Where”, he describes a cacophonous performance,

Take a cheese grater to your cortex

or eavesdrop on the god of thunder kazooing Dumbo

followed by the inter-county T-Rex throat-clearing competition

the humour is again in evidence, as is his liking for making words and images surprise, often by juxtaposing words that don’t on the face of it seem to have much to do with each other:

Sheen a fin with oil

A tall failed owl egg roaring

Beaned arse loo

Hard town dull redneck cooing

(“Anthem”)

Sometimes this works for me; sometimes not. With the scientific vocabulary, though it is unfamiliar, I can look it up. Also there are other ways in, for he is as apt to play with language as with science. The title “Solation” apparently means the liquefaction of a gel, but I saw it as “isolation without an I”, an interesting concept. What looks like random word association, though, is harder to fathom unless one happens to be inside the poet’s head. “Anthem” baffled me throughout; the Gaelic in the last verse no more puzzling than the English. On the other hand, “Exit Like A Frog In A Frost”, though I’m still not sure just what the images are doing, is haunting, as Rilke’s images sometimes are before the brain ever gets around to analysing them:

there was a universe

than which no sweeter

could be imagined

door after door slamming

through a tumult pouring down

from galleries

of women and children in cages

so utterly bewitching

and the waters tumbled as stones

and with lightning the stones were broken

One thing that intrigues me is the occasional word inversion, eg “tender skull-mounted orbs which next to nil assimilate” (“Minoan Miniatures”) and “But if we from natural processes result” (“The Road To God Knows Where”). This is such a no-no in contemporary poetry that it must be deliberate, but I haven’t worked out what he means it to do, unless it is another way of surprising the reader and putting him/her off balance. If so, it is quite a daring thing to do, as, arguably, it is for an Irish poet, post-Heaney, to write about bog bodies in “Outtakes”.

A standout poem, for me, was “Semper Ubique”, in which the many-worlds theory of quantum mechanics becomes a poem even a technophobe like myself finds both moving and comprehensible (though in another universe I am presumably still scratching my head).

I didn’t think I’d be so scared

in light’s careless flux

so many worlds conjured

so that what can happen must.

“What does it mean,” asked Aniela,

“if ghosts so often appear

surrounded by light

or transparent, or headless, or white?”

always and everywhere

extravagant remote

the girls’ skeleton hands

resting

where strings once stretched.

(If only it were true

that what should not happen could not.)

March 1, 2024

Review: The Dreadful History and Judgement of God on Thomas Müntzer, by Andrew Drummond, Verso 2024

Look: the origin of usury, theft and robbery lies with our lords and princes, who treat all creatures as their own: the fish in the water, the birds in the air, the plants on the earth – everything must be theirs.

Look: the origin of usury, theft and robbery lies with our lords and princes, who treat all creatures as their own: the fish in the water, the birds in the air, the plants on the earth – everything must be theirs.

On 15 May 1525, a few thousand German peasants, under the rainbow flag of the Peasants’ Revolt, faced two armies of mercenaries, infantry, cavalry and artillery, who duly annihilated them at a place afterwards known as the Schlachtberg (Slaughter Mountain). One of their leaders was Thomas Müntzer, subsequently captured, tortured and executed. He was an intellectual, a Reformation minister who composed hymns and services in German, rather than Latin, so that his working-class congregation could actually understand what was going on (“It can no longer be tolerated that men attribute some power to Latin words, as if they were the words of magicians, nor that the poor people should leave the church even more ignorant than when they entered”). How then did he arrive at the Schlachtberg?

Andrew Drummond writes both fiction and history (sometimes, as in his novels

Novgorod the Great

and

The Books of the Incarceration of the Lady Grange

, both at once). This is emphatically history and, though written in his usual lively style, is scrupulous in its evaluation of sources, its distinction between what is known and what can be speculated (important in a life for which there are several poorly documented periods) and ardent in its zeal to correct the “veritable cottage industry of falsification” that has been spread about Müntzer ever since his death, mainly by Dr Luther and his allies.

The basis of Müntzer’s theology, and what alienated him from both Catholics and Lutherans of his day, was his belief in “the opposition between ‘living voice’ and ‘dead word’, present and past. This opposition was the most basic dialectic in Müntzer’s thought, and from it can be traced much of his other philosophy. He argues that the work of God did not stop when Jesus died, but that it continued and continues in the spirits of true Christians. These Christians perpetuate the ‘living Gospel’ in themselves, as people predestined to execute the will of God on earth.”

Or as he put it, “Where the seed falls on good ground, that is in the heart which is full of the fear of God, that is then the paper and parchment upon which God writes the real spiritual word, not with ink, but with His living finger”. It followed that he disagreed fundamentally with those who felt that the common man’s role in church was to listen to what his betters told him and leave doctrinal points to be argued between scholars – “the scholars should read beautiful books, and the peasant should just listen, for faith comes through listening. Ah yes, they’ve found a nice trick there.” Hence his insistence on services in the vernacular.

Luther too had of course advocated for using the vernacular, and for other reforms, but around 1522 he rowed back quite considerably from this position, even reinstating Latin services on the somewhat ludicrous ground that this would encourage people to learn Latin. The truth was that in his quarrel with the Church he relied heavily on the support of the German aristocracy and would do or say more or less anything to avoid offending them. It is one of Müntzer’s major quarrels with him: “The fact that you were able to stand before the Empire at Worms is all thanks to the German nobility, whose mouth you have smeared well with honey”. The language of debate at the time was vitriolic and Müntzer is a match for Luther in this respect, but the difference between them is that Luther punched down while Müntzer punched up. Luther could be downright scatological about people he disliked who were below or on a level with him, but his language to the gentry – “To the most shining, high-born princes and lords, Lord Friedrich, Elector of the Roman Empire, and Johann, Duke of Saxony, Landgrave of Thuringia, and Margrave of Meissen, my dear lords…” could not be further from Müntzer addressing Count Albrecht, “Do you really think that God has less interest in his people than in you tyrants?”, or Count Ernst: “Now tell us, you miserable, wretched sack of maggots – who made you into a prince over the people whom God redeemed with his own precious blood?” Müntzer and tact never had even a nodding acquaintance.

And Müntzer, who lived among working people, could not share Luther’s contempt for them, or the Wittenbergers’ insistence that they owed total obedience to their feudal lords. Hence his presence on the Schlachtberg, while Luther was fulminating, “The peasants […] are so disloyal, false, disobedient and wanton, and plunder, rob and remove what they can, like barefaced highwaymen and murderers”. In fact Müntzer’s peasants killed very few, in comparison with the nobility. Drummond remarks of 15 May: “It is estimated that between 5,000 and 7,000 rebels died that day – the figure is understandably approximate, but surprisingly consistent over several reports – with a further 600 taken prisoner. Half of the adult male population of Frankenhausen was put to the sword. For the nobles and their troops, the affair was treated almost as a sport: two minor aristocrats sent to the campaign by Prince Joachim von Brandenburg had been commissioned by their sponsor to bring home the ear of a peasant; in a letter, they regretted that this had proved impractical.” (Luther’s comment was “Yes, it is to be regretted. But what else could one do? It is essential that the people be frightened and cowed”.)

Though the Revolt, and Müntzer’s part in it, are put down among the “failures” of history, Drummond convincingly shows how his influence survived and inspired later campaigners. And as usual, he does not feel that writing “serious” history obliges him to abandon his dry humour, which enlivens many a page: “His [Luther’s] letter also discussed infant baptism and the vexed question of whether faith can be sprinkled upon babies, coming down firmly on the fence”. I was particularly taken with the eclectic shopping list of one Glitzsch, a curate in an isolated country parish: “a selection of the latest books by reformers, various vegetable and herb seeds – beetroot, marjoram, hyssop – a measure of saffron, some assorted nails and screws and, of course, two sows and one uncastrated boar – the latter reflecting Glitzsch’s pressing need to get to grips with husbandry.”

Apparently Müntzer used his final words “not to make a full confession, as was traditional, but to warn the princes not to punish the poor any further and to take heed of the biblical Book of Kings, in which it was explained how pious rulers should act”. I am left remembering his words in yet another tactless letter to some noble or other: “And you should know that I do not fear you or anyone in the whole world in these great and just matters.”

February 16, 2024

Review of Revolutionary Spring: Fighting for a New World 1848-1849, Christopher Clark, Penguin 2023

Strangers embraced like brothers and ‘men of grave demeanour’ were seen ‘leaping and singing in the public thoroughfares’

As Clark points out, this contemporary account of the revolutions in 1848 could as easily have described the 'Arab Spring' protests of 2010, and it is a comparison he will make again. Like him, I was taught in school that the revolutions of 1848 ‘failed’, because they didn’t last. Clark is concerned in this book to show that this isn’t really the case. Pretty much everywhere in Europe, although there were counter-revolutions, they did not take their countries back to the status quo ante, because too many things had changed and monarchies, having been reminded of their mortality, were terrified of them changing again. Certainly the radicals, who saw revolution as a continuing process that would only end when the last king had been strangled with the entrails of the last priest, would have seen them as failures. But the moderate liberals who simply wanted things like a wider franchise and fairer distribution of resources would have had reason to feel vindicated.

Clark charts the conditions that led to 1848, the events of that year, when “what was scarcely conceivable yesterday is reality today and history tomorrow”, the counter-revolutions and the ultimate effects of all these events. For the first of these, the lead-up, he naturally has to go a fair way back; one cannot discuss 1848 without first examining 1830, and then there is the effect of the French Revolution on that… when reading history, one soon begins to think Cecil B de Mille may have had a point and that the Book of Exodus probably is somehow relevant to the Wars of the Roses.

Luckily the lead-up is in its way as fascinating as the main events. Clark handles his cast of thousands well, moving between countries all over Europe without confusing the reader. He is particularly good on the split, present from the start, between liberals and radicals, and on the problematic fear, among liberals, of the working classes who went out on the streets to fight. The moderates were never absolutely certain that ‘the mob’, having finished with the aristocracy, might not come for middle-class property owners as well ('The landowners invoked the sanctity of property, but the peasants, as James Morris observes, “refused to recognise property as sacred until they had some of their own”.’) As Clark remarks of Guizot in France; ‘he embodied the ambivalent pathos of those political actors who hope to arrest the process of change at what seems in their eyes to be the optimal moment’. This was one reason for the plethora of constitutions that sprang up after the revolutions; liberals saw them as ‘peace treaties designed to manage the relations among structurally antagonistic groups’.

And there were plenty of those. Class, nationality (or more often regionality), religion, were all dividers, and how people defined themselves depended on which was most important to them at the time. When, in 1846, Polish nobles in various locations in Galicia rose up against the Austrian empire and invited their peasant workforce to be cannon fodder, they were genuinely astonished to find that said peasants in no way identified with them and indeed preferred the Austrian emperor, he being further away. It was at this point that the nobles usually regretted telling the peasants to bring along their flails and scythes. If they were lucky, the peasants merely overpowered and arrested them but mostly they slaughtered them.

For some months in 1848, though, many did make common cause, and the heady joy of those days, plus the frenetic pace of events, is well conveyed. In Milan, ‘astronomers and opticians took up positions in observatories and on the city walls to discern the movements of the enemy outside the city walls’. They sent their reports down via ziplines, where they were picked up by students who rushed them to the insurgents. Enrico Dandolo wrote of ‘universal joy and affection’.

Once in power, however, the revolutionaries faced problems not just from their enemies but within their own ranks, principally, as Clark puts it, ‘the difficulty of synchronizing the slow politics of the chamber with the fast politics of clubs and streets’. Those who had put their lives on the line wanted Utopia at once; the men now in power could see that this was impossible. ‘Men’, by the way, is exact; while in most places the revolutionaries were doing what they could to emancipate and, to a very limited degree, to enfranchise peasants, Jews and slaves, nobody in power anywhere was proposing to extend the franchise to women.

The personal violence, both by the revolutionaries and later the counter-revolutionaries, is breathtaking and reveals how polarized European societies had become. Yet there was, after things settled down, a kind of synthesis; constitutions were amended but not discarded; the franchise was extended, though nowhere near enough, and there was a huge expansion in public works – railways, civic planning and building. Some of this, like Baron Haussmann’s wide boulevards in Paris, was aimed at making it harder for 'the mob' to build barricades or vanish down side alleys. But it was also about providing work and lessening public discontent. Censorship of news, too, eased as politicians found less obvious ways of managing it.

This book is not only thorough and comprehensive but very readable. Its major figures, like Robert Blum, come alive and engage one’s sympathy, and there are unforgettable vignettes along the way, such as the London special constable, recruited to combat the Chartists, who would later be known as Louis Napoleon III. Probably my favourite incident concerns the small town of Votice, in what is now the Czech Republic. After the counter-revolution, Votice was ordered to surrender its revolutionary guns, banner and drum. This proved awkward. The banner had been returned to its original role as a weathervane on the town hall. Nor could the drum be spared, as it was the municipal drum used to announce civic events. As for the guns, it turned out they were facsimiles the citizens had carved from wood, all except one, which the local potter had made out of clay. Few stories could show so plainly how much the folk of Votice had wanted to be part of this great event.

February 1, 2024

Review of The End of Enlightenment, by Richard Whatmore, pub. Penguin 2023

book cover

book cover In 1776, David Hume, near the end of his life, speculated on excuses he might give to Charon when invited to step into his ferryboat: “If I live a few years longer, I may have the satisfaction of seeing the downfall of some of the prevailing systems of superstition”. But Charon would then reply, “You loitering rogue, that will not happen these many hundred years. Do you fancy I will grant you a lease for so long a term? Get into the boat this instant.”

Hume belonged to a generation of thinkers who “tended to see themselves as postwar generations. Between the sixteenth and early eighteenth centuries Europe rarely saw a year of peace. The Enlightenment began when these religious wars ceased.” To his mind, fanaticism and bigotry had been replaced by tolerance and calm, with opposing parties able to argue rationally instead of attempting to outlaw or kill each other. What concerned him as he awaited the ferryman was the fear that old times might be coming around again, but in a different guise.

Hume had once thought that increasing commerce between nations would of itself make war less likely – trade flourishes best in peacetime, and states which may heartily dislike each other’s politics and religion will nevertheless maintain at least polite relations for the sake of their mutual profits. But in fact trade wars had replaced religious ones, and states were empire-building through war to protect and expand their trade, and to satisfy the appetite for luxury goods that this trade created in the populace. The mutual dependence of governments and merchant companies worried philosophers and political economists like Adam Smith; “Merchant companies made their own interests sovereign, he argued, to the detriment of indigenous peoples who became only a source of profit, and to domestic governments, who became their fools”.

Nor had fanaticism vanished; it had simply moved from the realm of religion to that of politics. Hume “believed that British politics had become increasingly polarized between camps that portrayed those with different views as beyond the pale, as supporters of despotism or anarchy”, and it is hard to disagree with him when one reads rhetoric like Burke’s on the “wicked principles and black hearts” of men like Richard Price and Lord Shelburne, who, however much they may have disagreed with him, were demonstrably neither unprincipled nor black-hearted. They would have classed themselves as moderates, as indeed Burke classed himself; it is remarkable how politicians and thinkers on all sides of the argument saw themselves as moderates and their opponents as fanatical zealots. Politicians, particularly the Whigs who had been in power for most of George II’s reign, also tended to confuse their own interest with that of the nation; when they lamented that the country was going to the dogs, what they generally meant was that they personally were out of office.

Almost none of them, indeed, had any faith in the ability of the general public to elect the right men, manage affairs, or cope with any kind of power. Shelburne, an amiable sort who genuinely desired the “Happiness of Mankind”, also confessed to being ‘sorry to say upon an experience of forty years, that the public is incapable of embracing two objects at a time, or of extending their views beyond the object immediately before them’. He, and others, felt that democracy led to the public being bamboozled by jingoistic demagogues (and if they were alive today, they might well feel vindicated in that view). Wollstonecraft, who had once thought people were naturally virtuous or could soon become so, wrote in 1796 that she had ‘almost learnt to hate mankind’. Obviously some of this was owing to disillusion following the chaos into which the French Revolution had descended; it does not seem to have occurred to many that the excesses of the previous monarchy had in large part caused this violent swing. Burke, fulminating about ““a discontented, distressed, enslaved, and famished people”, gives no hint that this had been exactly the case under the old regime as well. It might have been supposed that regimes elsewhere would learn not to imitate Bourbon intransigence, but in fact they became ever more illiberal out of fear for their own privilege and landed interests. Gibbon was convinced that any concession to political reform would be fatal – “if you do not resist the spirit of innovation in the first attempt, if you admit the smallest and most specious change in our parliamentary system, you are lost”. He “shuddered” at the plans of Charles Grey, who would go on to steer the 1832 Reform Bill to success.

This study, which would take an essay to review in detail, records and analyses the reactions of thinkers including Hume, Burke, Paine, Wollstonecraft, Catharine Macaulay, Gibbon, Shelburne and Brissot to the end of the Enlightenment years and the American and French revolutions. It also sees this period as analogous in some ways to our own, in that now too, political discourse and much else seems to be polarizing, fanaticism and intolerance to be on the rise and a spell of relative peace coming to an end. In many ways it is less a history book than a book about theories of history, which could easily have been unreadably dull; fortunately it is written with great clarity and allows the characters of its fiercely intellectual protagonists to come across, often via their own words. Even Wikipedia, that fount of knowledge-substitute, gives no hint that the phrase “the silent majority” did not originate with Nixon or Coolidge, nor yet as a humorous Victorian description of the dead, but may be found in Mary Wollstonecraft’s description of the poor of Britain as “a silent majority of misery”.

January 16, 2024

Review of Scotland's Forgotten Past, by Alistair Moffat, pub.Thames & Hudson 2023

“History is memory”.

I like the idea behind this book, namely to dismiss kings and battles for once and to write the history of “this quirky, bad-tempered little nation on the northwest edge of Europe” via incidents and people that generally get forgotten about. I’m all for this approach, putting the bird-brained Bonnie Prince to one side and highlighting instead people like Tom Johnston, who in his role as wartime Secretary of State for Scotland effectively trialled a sort of prototype version of the NHS:

“Fearing more air raids, especially on the heavy industry of the west of Scotland, Johnston set up the Emergency Hospital Service. At safe locations, well away from cities and factories, at Raigmore in Inverness, Peel in the Scottish Borders, Law in North Lanarkshire, Stracathro in Angus, Ballochmyle in Ayrshire and Bridge of Earn in Perthshire, hospitals were quickly built to cope with a flood of casualties. When the expected bombs did not fall […] Johnston did not hesitate […] he filled the empty hospitals with patients whose care and operations had been delayed because of the war, or because they could not afford them. By 1944, more than 33,000 Scots had been treated, and none had paid a penny.”

There was a man who has most certainly been overlooked, and who was far better worth remembering than some drunken aristocrat – speaking of which, I was also amused by the fact that one of the very few posh folk who rate a mention is the wartime Tory MP for Peebles and Midlothian, Capt. Archibald Henry Maule Ramsay, a demented anti-Semite who had somehow persuaded himself that Jean Calvin’s real surname was Cohen and that the Soviet Union was dominated by Jews. On the one hand, it is perhaps reassuring that potty conspiracy theorists were around back then as well; on the other, it is sobering to realise that these days he would have a website and a following of gullible idiots. Back then, the authorities simply murmured “they’re not all locked up yet” and proceeded to rectify that matter.

Many of the 36 vignettes really are from such forgotten corners of history and are well chosen. Among these are the horribly fascinating prehistoric rituals at the Sculptor’s Cave, near Lossiemouth, the almost equally grisly experiments of Enlightenment professors on executed murderers, the unexpected influence of Islington Council on the legal definition of Scotch whisky (“The role of Islington Council in the development of the branding of Scotch whisky is sometimes overlooked”) and the blacksmith James Small who invented the modern ploughshare. From times within living memory, Moffat’s evisceration of the TV programme The White Heather Club will strike a chord with many:

“It was a strange, mostly nauseating, version of Scottish culture, a random, cringe-making mash-up of bits and pieces from the Kailyard (a Lowland tradition of popular songs, usually about the countryside), what the producer imagined a ceilidh to be, and the Victorian obsession with tartan and the Highlands. The White Heather Club was undoubtedly a harking back to a past that never existed, a musical and televisual Brigadoon.”

If all the episodes were like these, I’d have nothing but praise. But sadly, some do focus on better known and not at all forgotten individuals, and in these sections I found myself skim-reading what I already knew well enough. I would happily have discarded William Wallace for Hugh Millar, James Barrie for Elizabeth Melville and Robert Carey, who was a footnote to history but deserved no better, for John Williamson (Johnnie Notions, as we know him here in Shetland). Basically I think we have here a good idea that could have been better carried out. But the style is fluent and pleasing, and there’s no doubt he has unearthed many a fascinating fact from the midden of history. I was particularly taken with the effect of the invention of porridge on the prehistoric birth rate.

January 1, 2024

Review: The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho, by Paterson Joseph, pub. Dialogue Books 2023

"Strangely, though I was flattered by my employer’s decision to have my likeness taken by Mr Gainsborough, my mind was very much elsewhere. I had come so far in my turbulent life to this point. Gazing upon me in my finery (a costume, after all), these folks could have no idea how I came to be in this fortunate position."

I’m stepping out of my custom here, which is not to review books that don’t need any extra publicity. But in this case, it struck me that some of my friends who like litfic and hist fic might miss out by mistaking the kind of book it was. Seeing the name of a famous actor as author, plus endorsements from the likes of Stephen Fry, might lead some to think “oh, another celebrity who thinks he can write novels”. And that would be an error on their part, because this one most emphatically can.

Our protagonist-cum-narrator is Charles Ignatius Sancho, c.1729-1780, writer and musical composer, also, from time to time, butler, valet and shopkeeper, active in the abolitionist movement, which was hardly surprising as he had been born to a captive woman on an Atlantic slave ship. Orphaned soon after birth, he was a Londoner from the age of about two and overcame his somewhat shaky start to become, among other things, the first known British African to vote in a general election (for Charles James Fox, huzza!), the first to publish a collection of letters and the first whose obituary was published in the British press.

Joseph could presumably pick up Sancho’s spoken idiom from the man’s letters, but it is not just the voice he has hit off so convincingly; it is also the whole ambience of Georgian London. It’s a period and place in which I have done some immersing myself, thanks to Mike Rendell’s histories, and I have not seen its streets, coffee-houses and inhabitants better brought to fictional life. It is done so subtly that quotation will not work to illustrate it: Sancho does not indulge in poetic description of his surroundings; he just knows them, with an assurance that communicates itself instantly to the reader.

In many ways the story is of Sancho working out exactly who he is and where he belongs. Despite having spent almost his whole life in London, he never feels completely at home there and always resents its native inhabitants both for their attitude to him and for what they have done to his people. Yet, brought up as a sort of domestic pet among white people and with many more white than non-white acquaintance, he also for a long time feels estranged from, and resented by, the non-white community. In some ways, as he recognises, they are right to see him as privileged; he has known poverty but ends up able to cast a vote because he is a male householder who fulfils the necessary financial conditions, which lifts him above all women and about 87% of men at the time. His consciousness of this estrangement is part of what leads him to be, in later life, a campaigner for abolition, and his development in this direction is skilfully done, never more so than when Sancho, himself a musician and composer in the European tradition, hears African music for the first time in the Black Tar Tavern:

"The music that struck my ears was at first difficult to assess. Percussive sounds that moved in a time signature I was unfamiliar with – there seemed to be more than eight beats in each bar and the bars were not clear to my unaccustomed sensibility. It was as if one of Handel’s liveliest dance pieces were subject to an urgency that rendered the melody secondary to the rhythm – constant – imperative – wild. But there was something else to the music – something other than just the beat – the richness and detail of the harmonic layers created a sense of abandon.”

For a debut novel, this is astoundingly assured and in control of its material. I would guess it is based on the play Joseph wrote earlier about Sancho, and that it has benefitted from this earlier incarnation. This author is not a celebrity who thinks he can write; he's a writer who happened first to become famous in another field.

December 20, 2023

List of 2023 reviews

Here they be, sorted into poetry, fiction and non-fiction and with links to each.

Poetry

The Thirteenth Angel by Philip Gross, pub Bloodaxe 2022

Coldharbour by Kathryn Daszkiewicz, pub. Shoestring Press 2022

Goldhawk Road by Kate Noakes, pub. Two Rivers Press 2023

Never Still, Nivver Still by Joan Lennon, Anne Sinclair and Lucy Wheeler, pub. Hansel Cooperative Press 2023

The Dogs by Michael Stewart, pub. Smokestack Books, 2023

Poèmes Écossais by Paul Malgrati, pub. Blue Diode Press 2022

Eftwyrde by Bob Beagrie, pub. Smokestack Books 2023

Listening, Listening by Bob Cooper, pub. Naked Eye Publishing 2023

Fiction

My Pen is The Wing of a Bird: New Fiction by Afghan Women, pub. MacLehose Press 2022

The Confession of Hilary Durwood by Euron Griffith, pub. Seren 2023

The Secret Life of Carolyn Russell by Gail Aldwin, pub. Bloodhound Books 2023

Shifts by Christopher Meredith, this edition pub. Parthian 2023

The Whalebone Theatre by Joanna Quinn, pub. Penguin 2022

Non-fiction

The Marchioness of Peru vol 1 by Creina Francis, pub. 2022

The Grand Tour by Mike Rendell, pub. Shire Publications 2022

Black Ops & Beaver Bombing by Fiona Mathews and Tim Kendall, pub.Oneworld 2023

Weavers, Scribes and Kings: A New History of the Ancient Near East, by Amanda H Podany, pub. OUP 2022

Trailblazing Women of the Georgian Era, by Mike Rendell, pub. Pen & Sword History 2018

An Illustrated Introduction to the Georgians by Mike Rendell, pub. Amberley Publishing 2014

Woman, Captain, Rebel by Margaret Willson, pub. Sourcebooks 2023

The Dawn of Language by Sverker Johansson, trs. Frank Perry, pub. Maclehose Press 2022

Infamy: The Crimes of Ancient Rome, by Jerry Toner, pub. Profile Books 2020

Buried by Prof Alice Roberts, pub. Simon & Schuster UK 2022

The Stasi Poetry Circle by Philip Oltermann, pub. Faber 2022

December 16, 2023

Review of Listening, Listening by Bob Cooper, pub. Naked Eye Publishing 2023

and I want to remember this, all of this, because it happened.

This last line from “To be continued” highlights two important qualities in Cooper’s poetry: it is observational, and much concerned with everyday life. What he is so anxious to recall is the woman and child who sat in front of him on a bus; their rapport with each other, their apparently slender means. This is all he could glean of them in a short time; there was no actual interaction, but as the title implies, after they got off the bus and vanished from his knowledge their lives went on. This title is actually unusual in pinpointing what for him is central to the poem. Another such, “Elsewhere she’ll fumble her flat’s key into the lock”, again speculates on the part of people’s lives the poet cannot see; in this case unexpectedly humanising an internet troll or scammer. Her fake profile shows her

in a ribbon-adorned US army uniform

on a sunlit porch, a tied-back-tight-ponytail-haloed smile,

and her listed Facebook friends, each with glossy teeth

But the poet wonders about that “elsewhere”:

how many of them are click-my-box trolls, too,

in the same fluorescent-lit fourth floor room in St. Petersburg,

keyboard-clicking demotivational posts on their afternoon shift.

Will she then wait for a tram with a half-full shopping bag

cursing herself quietly because, even though it’s pay day

and she’s bought her son socks, she forgot a lightbulb.

So, again, she’ll walk the corridor to her flat in the dark.

Some other poems use the first line for a title, even when this is fragmentary – eg “Before sunrise, eating muesli, I decide that”. Others seem to hunt for determinedly “quirky” titles – eg “One of the times when Willie Long-Legs and Laudanum Sam met Mazy Mary and Sarah Snuggles”. Maybe it’s just me, but I tend to feel a thoughtful, thought-provoking title, that you go back to and see new meaning in once you’ve read the poem, is a good sign, an indication that the poet knew what was important enough to make him want to write it and what he wanted his readers to take from it. Also, quirky drives me nuts. So it may be no accident that his observing-everyday-life mode, in which the titles tend to be more sober and considered, is where most of my favourite poems in this collection can be found.

The observation is often quite sharp, as in

How his smile muscles were so under-used that

when they twisted, tightened, I was always surprised

from “What the district nurse never included in her report”, and the “clouds of luminous breath” in the autumnal “Those on the ball before darkness surrounds them”. This poem is one of several where he goes beyond observation to find the universal in the particular, and again he is conscious that the people he is watching exist beyond the moment of his poem:

and everything beyond all this is also here

in this November afternoon

When not observing life around him, he does a lot of what-iffing, particularly about dead writers – “Rilke in his Audi on the M53”, “O’Hara and Melly meet up in Liverpool”, “M/s Eyre’s lover visits a writers’ course at Lumb Bank” and several more. I think there are a few too many of these and that some begin to sound like exercises. One that does work beautifully is “Almost meeting Keats on the doorstep”, in which tourists entranced by the museum that was Keats’s villa in Rome ignore the “pale-faced twenty-something” on the doorstep who could be Keats and surely has his illness:

He coughs, smiles politely, asks for one euro so that he can get in.

They ignore him and keep talking – the bedroom and bed were so tiny.

Only the wallpaper’s changed. Locals were scared of infection.

T.B.’s so contagious. Apart from that, it’s the same as when he died.

They keep chatting, open an umbrella in his face. He turns away.

There are a few typos, notably “Hurworth” for “Haworth” and “MacDonald’s” for “McDonald’s” – that one is surprising, for one of the virtues of this collection is its easy familiarity with contemporary references. Netflix, Facebook, Amazon etc all seem perfectly at home and not dragged in for effect as sometimes happens when poets are desperately trying to keep up with the zeitgeist. And for such a sharp observer, I thought the reference to “pensioners” drinking Ovaltine was a bit of a cliché, but maybe this pensioner is unusual in never having done so…

But though I think it would be a stronger collection with at least 15 pages fewer (almost any collection of 100 pages could afford to lose that many), there is much to enjoy here, perhaps nowhere more so than in the interesting “Miss Roberta Frost and the owls”. This is a sort of reverse sonnet, sestet first and octave second. It is of course partly another what-if, as witness the lady’s name and the echoes from “Acquainted with the Night”. But the character, and the emblematic owl, exist on their own terms, and memorably:

All she hears is the pad of shoes as her feet

climb the stairs to undress, lie still, and the cry

of an owl cruising along his airborne street,

unseen, always aware, not saying good-bye

to his mate but telling her where he is – height

and distance – as he ghosts the empty sky.

Then he answers her call, turns.

December 1, 2023

Review of The Stasi Poetry Circle by Philip Oltermann, pub. Faber 2022

Lance-Corporals of Love

Who knew? That the Stasi, East Germany’s secret police, when not prying into people’s private affairs, destabilising marriages and generally messing up lives, met to study the sonnet and produce anthologies of poetry? But then, as Oltermann points out “the history of the GDR is a book usually read back to front”. We all know, indeed some of us saw, the latter days of the paranoid gerontocracy, trying to make fear do the work of the enthusiasm they could no longer engender. But it is easy to forget that some of those who first set it up were imbued with genuine idealism and a desire not only to reclaim Germany’s impressive cultural heritage but to make it more available to the masses than it had ever been.

Johannes Becher, returning from Russian exile to postwar devastation, gave up his own writing to become a political fixer and give art - “the very definition of everything good and beautiful, of a more meaningful, humane way of living” - an honoured place in the new republic. Though he died in 1958, his dream of bringing artists together with workers survived him. “Theatres and opera houses handed out a proportion of their tickets to factories and educational institutions. A 1973 decree prescribed that larger factories must have an on-site library.” And the “Bitterfeld Path” programme sent writers out to run workshops among workers. “Within a few years every branch of industry had its own writers’ circle, by the end of the GDR in 1989 there were still 300 of them.” Christa Wolf, Brigitte Reimann and Erik Neutsch all wrote famous novels while on such placements.

However things finally turned out, these initiatives were clearly laudable. So what went wrong? Becher’s own view of the sonnet may give a clue. He saw it as the artistic expression of dialectical materialism, with the octave as the thesis, the first four lines of the sestet as the antithesis and the final couplet as the synthesis. But things just aren’t as tidy as that, nor do artists of any calibre generally feel at ease as part of a political establishment and singing its tune. It didn’t help that the government censors were hugely distrustful of the poets, feeling that the artful fellows were taking advantage of their ignorance of poetry to sneak sedition past them, as indeed they were – Uwe Kolbe’s subversive poem “Core of my Novel” got past in 1981 because the censors didn’t know enough to look for acrostics.

Their solution, typically, was not to give up trying to censor writing, but to employ spies better versed in these techniques, and the leader of the Stasi writing group, the really rather obnoxious Uwe Berger, was regularly writing intelligence reports on his students. Also, of course, their work was being directed into what he saw as useful channels. In the group’s early days, the younger students especially were keen to write love poetry and at first this was tolerated, until it became clear that this tended to political incorrectness:

“One young member of the secret police fantasised in free verse about being kissed by a young maiden unaware of his lowly rank, thus elevating him to a ‘lance-corporal of love’. ‘Patiently I wait’, the lusty teenager wrote, ‘for my next promotion/at least/to general’. Another young soldier imagined in a sestina writing the words ‘I love you’ into the dark night sky with his searchlight.” The energy, humour and inventiveness of these poems was promising. Alas, when the young poets began expressing the wish to have the beloved all to themselves, “never to be nationalised”, they were hastily guided into duller channels.

When they did manage to express genuine talent without interference, it was sometimes because they themselves were also working undercover for the state. This was the case with the group’s most talented poet, Alexander Ruika, though it also sounds as if he was not only coerced into it but produced reports his masters must have found singularly unhelpful. The three-way conversation between Ruika, Oltermann and the novelist Gert Neumann, on whom Ruika had gathered intelligence, is fascinating, as is the way Neumann baffled the government, not only because they couldn’t for the life of them understand his prose but because, though a constant thorn in the establishment’s side, he showed no desire to leave for the west and indeed worried that if he did a western tour, as some writers did, he might not be allowed back in. It never seems to have dawned on them that criticism did not necessarily mean rejection.

I’d have loved to see some of the poems from which Oltermann quotes reproduced in the original German in an appendix, which could have been a real asset. But this is otherwise a most informative, balanced and thought-provoking book.