Sheenagh Pugh's Blog, page 4

August 16, 2024

Review of A Grand Tour of the Roman Empire by Marcus Sidonius Falx: Jerry Toner, Profile Books 2022

Jerry Toner is a classical scholar who specialises in writing accessible versions of Roman social and cultural history. This book is an account of a “grand tour” through the Roman empire at around the time of Antonius Pius by an imaginary Roman aristocrat called Marcus Sidonius Falx and his amanuensis, a “Brittunculus” called Jerry Toner. In each chapter Falx gives his impressions of various bits of Empire while Toner adds his own commentary afterwards.

The point of this narrative method is to give us the tour of the empire as it appears to Falx, an archetypal Roman aristocrat who, while not in himself an unkind man, sees nothing wrong with slavery, conquest, vast inequality and brutal repression of all who don’t buy into the pax romana. He thinks the Roman Empire is the best thing that ever happened to the world, which is natural enough since it runs, and is designed to run, for the benefit of people like him. At the end of each chapter, Toner in his character of amanuensis can give a somewhat corrected view. An incidental benefit is that this method enables Toner to give Falx a character, which ends up being surprisingly individual and credible, despite the fact that his words, impressions and experiences are an amalgam of umpteen real people who left us their writings on the places he visits. Although it’s evident if you read carefully that Falx cannot be writing earlier than the reign of Antoninus, and maybe a bit later (at one point he notes that “recently, the emperor Antoninus Pius extended the sanctuary and his imperial patronage has only added to the popularity and prestige of the place”), the people and events on his travels are drawn by Toner from various reigns.

erFalx is, in fact, a sort of composite Roman Aristocrat, being used to embody the kind of things that happened to people like him because the Empire was how it was. It’s quite impossible, for instance, that Falx, an echt Italian-born Roman, could have been the father of Aelius Brocchus, an officer on Hadrian’s Wall who was probably from Batavia (modern-day Netherlands), nor could he have attended the birthday party of Brocchus’s wife Claudia Severa in Britain in around 100 AD, given that the journey on which he was engaged at the time can’t have taken place earlier than 138 AD, when Antoninus’s reign began. But this sort of thing doesn’t really matter, because Falx is a representative figure and it is actually quite entertaining when on his travels he comes across people (albeit unnamed) or events we know from elsewhere. Claudia Severa’s birthday invitation to her friend Sulpicia is one of the most famous of the Vindolanda tablets; most readers will be happy to see her again and to assume that a man like Falx might well have a son serving on the Wall, whatever his name may have been.

And it’s a sheer delight when Falx, an arch-snob with a keen appreciation of art, is entertained by a Romanophile Briton whose pronunciation of Latin is reminiscent of Officer Crabtree’s French from ‘Allo! ‘Allo (“‘Groatings!’ he cried, ‘Long live the umperor!’ It was going to be a long couple of days”) and who possesses one of the most ineptly executed (and ill-spelled) floor mosaics in the Empire:

“On the floor was a fearful mosaic of some hideous harpy. ‘Your craftsmen have certainly captured the very likeness of the monster’, I commented. ‘Monster?’ he replied in bewilderment […] It is surely Venus after winning the beauty contest’. The female figure was naked and her long hair stuck out wildly. Her lower body and hips were oversized, while her legs tapered to tiny feet. […] If this is the Britons’ ideal of beauty, I can only pity their men.”

I have seen pictures of this remarkable mosaic (from a villa in Rudston, Yorkshire); it’s third-century, but who cares? It was an old friend which probably represented many such clumsy efforts at Romanising, and hence has a place in this composite picture.

All through the book, interest is generated both by the ways in which Falx’s world resembles ours, and by the ways in which it differs. He uses a version of the Peutinger Map, a medieval copy of a Roman original which was “a practical shorthand that helped the traveller plan their journey by representing the communications network, in a similar way to the London Underground map, which helps tourists traverse the capital while bearing only a vague likeness to the geography of the city above ground”. It also used symbols as guides do today – “The inns are represented by different symbols according to their quality. A sign of a building with a courtyard means that it is a high-class inn, whereas a drawing of a simple box house with a single peaked roof means that the traveller can expect a modest establishment at best”. The souvenir trade has not changed much, either; “Miniature replicas of the Parthenon are very popular as are glass vials with pictures of all the city’s chief sites identified by labels. The miniature temples are available at a range of prices, with silver being the costliest and terracotta the cheapest”.

But then Falx will do or say something that brings home to us how far apart we are; “As we left one large town, we passed by an infant that had been abandoned by its parents, who by dint of poverty or some other inclination, had decided not to rear their offspring. The slave dealers or dogs would soon pick it up”. Or his observations on gambling; he only indulges “during Saturnalia when I let the slaves win. It costs me a few sesterces but it keeps them happy. And if it helps them buy their freedom eventually then I will get my money back in any case”.

Falx can be genuinely funny, often unintentionally: “The advantage in travelling with only the essentials was that it meant I needed the bare minimum of slaves, twenty or so at most”. And his travels and observations (plus those of his faithful though often disapproving amanuensis) are invariably not just entertaining but richly informative about how people actually lived under the Empire. My only cavil would concern the frame for Falx’s journey. Though many Romans travelled to visit their estates, or absorb Greek culture, or merely for pleasure, Falx is given an extra reason in the shape of having displeased a tetchy emperor, a motif that reappears at the end. This is the one time when the mix of periods doesn’t work for me. It might have, if the emperor in question had not been so clearly identifiable with Gaius, aka Caligula, but he’s too recognisable and too clearly out of his time. As far as I can see, Falx’s real emperor would have to be either Antoninus Pius or Marcus Aurelius, both of whom were, for Caesars, fairly amiable. I can guess Toner’s authorial reason for doing this: he wants to stress how unpredictable and dangerous life in the Empire could be, even for folk like Falx, but I wish he had made his “emperor” more generic. But I shall long cherish the image of Falx “completing the tour with a return journey down the Rhine, past the hairy barbarians on the further bank”.

Review of A Grand Tour of the Roman Empire by Marcus Sidonius Falx, Jerry Toner, Profile Books 2022

Jerry Toner is a classical scholar who specialises in writing accessible versions of Roman social and cultural history. This book is an account of a “grand tour” through the Roman empire at around the time of Antonius Pius by an imaginary Roman aristocrat called Marcus Sidonius Falx and his amanuensis, a “Brittunculus” called Jerry Toner. In each chapter Falx gives his impressions of various bits of Empire while Toner adds his own commentary afterwards.

The point of this narrative method is to give us the tour of the empire as it appears to Falx, an archetypal Roman aristocrat who, while not in himself an unkind man, sees nothing wrong with slavery, conquest, vast inequality and brutal repression of all who don’t buy into the pax romana. He thinks the Roman Empire is the best thing that ever happened to the world, which is natural enough since it runs, and is designed to run, for the benefit of people like him. At the end of each chapter, Toner in his character of amanuensis can give a somewhat corrected view. An incidental benefit is that this method enables Toner to give Falx a character, which ends up being surprisingly individual and credible, despite the fact that his words, impressions and experiences are an amalgam of umpteen real people who left us their writings on the places he visits. Although it’s evident if you read carefully that Falx cannot be writing earlier than the reign of Antoninus, and maybe a bit later (at one point he notes that “recently, the emperor Antoninus Pius extended the sanctuary and his imperial patronage has only added to the popularity and prestige of the place”), the people and events on his travels are drawn by Toner from various reigns.

Falx is, in fact, a sort of composite Roman Aristocrat, being used to embody the kind of things that happened to people like him because the Empire was how it was. It’s quite impossible, for instance, that Falx, an echt Italian-born Roman, could have been the father of Aelius Brocchus, an officer on Hadrian’s Wall who was probably from Batavia (modern-day Netherlands), nor could he have attended the birthday party of Brocchus’s wife Claudia Severa in Britain in around 100 AD, given that the journey on which he was engaged at the time can’t have taken place earlier than 138 AD, when Antoninus’s reign began. But this sort of thing doesn’t really matter, because Falx is a representative figure and it is actually quite entertaining when on his travels he comes across people (albeit unnamed) or events we know from elsewhere. Claudia Severa’s birthday invitation to her friend Sulpicia is one of the most famous of the Vindolanda tablets; most readers will be happy to see it again and to assume that a man like Falx might well have a son serving on the Wall, whatever his name may have been.

And it’s a sheer delight when Falx, an arch-snob with a keen appreciation of art, is entertained by a Romanophile Briton whose pronunciation of Latin is reminiscent of Officer Crabtree’s French from ‘Allo! ‘Allo (“‘Groatings!’ he cried, ‘Long live the umperor!’ It was going to be a long couple of days”) and who possesses one of the most ineptly executed (and ill-spelled) floor mosaics in the Empire:

“On the floor was a fearful mosaic of some hideous harpy. ‘Your craftsmen have certainly captured the very likeness of the monster’, I commented. ‘Monster?’ he replied in bewilderment […] It is surely Venus after winning the beauty contest’. The female figure was naked and her long hair stuck out wildly. Her lower body and hips were oversized, while her legs tapered to tiny feet. […] If this is the Britons’ ideal of beauty, I can only pity their men.”

I have seen pictures of this remarkable mosaic (from a villa in Rudston, Yorkshire); it’s third-century, but who cares? It was an old friend which probably represented many such clumsy efforts at Romanising, and hence has a place in this composite picture.

All through the book, interest is generated both by the ways in which Falx’s world resembles ours, and by the ways in which it differs. He uses a version of the Peutinger Map, a medieval copy of a Roman original which was “a practical shorthand that helped the traveller plan their journey by representing the communications network, in a similar way to the London Underground map, which helps tourists traverse the capital while bearing only a vague likeness to the geography of the city above ground”. It also used symbols as guides do today – “The inns are represented by different symbols according to their quality. A sign of a building with a courtyard means that it is a high-class inn, whereas a drawing of a simple box house with a single peaked roof means that the traveller can expect a modest establishment at best”. The souvenir trade has not changed much, either; “Miniature replicas of the Parthenon are very popular as are glass vials with pictures of all the city’s chief sites identified by labels. The miniature temples are available at a range of prices, with silver being the costliest and terracotta the cheapest”.

But then Falx will do or say something that brings home to us how far apart we are; “As we left one large town, we passed by an infant that had been abandoned by its parents, who by dint of poverty or some other inclination, had decided not to rear their offspring. The slave dealers or dogs would soon pick it up”. Or his observations on gambling; he only indulges “during Saturnalia when I let the slaves win. It costs me a few sesterces but it keeps them happy. And if it helps them buy their freedom eventually then I will get my money back in any case”.

Falx can be genuinely funny, often unintentionally: “The advantage in travelling with only the essentials was that it meant I needed the bare minimum of slaves, twenty or so at most”. And his travels and observations (plus those of his faithful though often disapproving amanuensis) are invariably not just entertaining but richly informative about how people actually lived under the Empire. My only cavil would concern the frame for Falx’s journey. Though many Romans travelled to visit their estates, or absorb Greek culture, or merely for pleasure, Falx is given an extra reason in the shape of having displeased a tetchy emperor, a motif that reappears at the end. This is the one time when the mix of periods doesn’t work for me. It might have, if the emperor in question had not been so clearly identifiable with Gaius, aka Caligula, but he’s too recognisable and too clearly out of his time. As far as I can see, Falx’s real emperor would have to be either Antoninus Pius or Marcus Aurelius, both of whom were, for Caesars, fairly amiable. I can guess Toner’s authorial reason for doing this: he wants to stress how unpredictable and dangerous life in the Empire could be, even for folk like Falx, but I wish he had made his “emperor” more generic. But I shall long cherish the image of Falx “completing the tour with a return journey down the Rhine, past the hairy barbarians on the further bank”.

July 31, 2024

Review of Belief Systems by Tamar Yoseloff, pub. Nine Arches Press 2024

A picture is more like the real world

when it’s made out of the real world.

Tamar Yoseloff has long been interested in poems that bounce off other art forms, witness her publishing company Hercules Editions, which specialised in the ekphrastic, often with illustrations. So it’s no surprise that she should produce a collection themed largely around paintings by Rauschenberg and music by Cage, with references also to other writers, artists and musicians – John Latham, Joseph Beuys, Jasper Johns, among others. Indeed the sequence “Combines” is illustrated with the Rauschenberg paintings that inspired it.

I may as well admit at this point that I had never before seen (or in some cases heard) any work by most of these folk, not being much into modern art or classical music. I did consider disqualifying myself from reviewing the book on this account, but that would seem to imply that only readers with the requisite background knowledge of Lives and Works could enjoy the poems, and having read several previous collections by this poet, I knew she would not have written anything quite so niche. Indeed in “Bridges”, though the reference to Wordsworth resonates with anyone who recalls the relevant sonnet, without that knowledge we would still have a striking poem about London (another recurring theme of hers) during the covid lockdown:

miss all those strangers, our city shut up

like an oyster worrying its pearl,

as I stick to my grid, never venturing

far enough to find the river’s glint

– all that mighty heart, as the poet said,

stopped, the monitor switched off.

The pandemic perhaps also lurks behind this collection’s consciousness of mortality:

Prints of dogs and hooves,

our heavy-soled shoes,

pressed in sand until the first

stiff wind – how simply

we lift from earth.

(“Common”)

The pessimistic description, in “New Year”, of

the season of fresh starts,

all those resolutions like cut pines

lined up for the bin men

is characteristic of the first part of this collection, shadowed by a brooding sense of things coming to an end; not just individual lives, but also perhaps a way of life, menaced by both the pandemic and the environmental crisis of which the poet is conscious; “it’s time to say goodbye to easy days” (“Summer Fields”).

Even in this first part, there are many references to, and riffs off, other writers and artists. The second part, “Combines”, is an ekphrastic response to Rauschenberg’s hybrid works “bringing together painting and collage with an assemblage of cast-off objects”, each poem being accompanied by an illustration of the relevant work. He talked, apparently, of “working in the gap between art and life”, or as Yoseloff puts it in “Trophy V (for Jasper Johns)”:

A picture is more like the real world

when it’s made out of the real world.

In the variant sonnet “Trophy IV (for John Cage)”, we get a sense not only of Rauschenberg gaining inspiration from the thingness of things – “A stroke of paint means nothing much/ but a boot speaks of endless journeys” – but also of how artists, even in different fields, feed off each other:

The composer gets a kick out of the artist

striking a blow for rag and bone.

The third part of the collection consists of the long poem “Belief Systems”. This is itself something of a collage; it was written in response to the exhibition The Bard: William Blake at Flat Time House, and owes its genesis to Blake’s illustrations of Thomas Gray’s poems, which in turn inspired his own poem cycles; to the world-view of artist John Latham, and to events in 2020, notably Storm Brendan. Again therefore we have art feeding off art, but also off reality, particularly the cast-off and abandoned, and the shadow of ecological catastrophe from the book’s first section is present here as well – if anything, more desperate:

nothing we’ve made will save us

from what we’ve razed. When the foaming

flood hits shore

our time is up.

*

The storm collects our waste.

Circuits bared, maps to nowhere.

Analog screens, their ancient stars

trapped in static. All of it shipped

to Surabaya; farmers ditch failed crops,

sift plastic for gold.

This is a brooding, urgent collection, the kind that both entertains and alarms. As I suspected, it is perfectly capable of being enjoyed without extensive background familiarity with Rauschenberg & Co, though the notes at the back are helpful and informative for those who want to mend their knowledge.

July 16, 2024

Review of A Darker Way by Grahame Davies, pub. Seren 2024

And, yes, they did those murals. You can tell?

No, not to everybody’s taste, but then,

neither was flaking whitewash, come to that.

The voice in “Traveller” is surely that of a schoolteacher, but behind it I hear two Roberts: the ventriloquism of Browning and the seemingly ambling narratives, with pinpoint phrasing, of Frost. The latter also feels like the presiding genius in “Happy Larry":

one of those characters, born middle aged,

that never stray five miles from where they’re born,

and in “Colleagues” – “The irreplaceable is soon replaced”.

Quite a few of the poems in this collection were commissions, some for songs (indeed the collection’s subtitle is “Poems and Songs”), which may partly explain the prevalence of regular metre and rhyme. It opens, however, with two poems about losing the impulse to write poems, seemingly because of a more untroubled life – “peace makes no poems” (“Scar”). The second of these, “Farewell to poetry”, would in my view be outstanding were it not for that title. It is really about the waning of desire, any desire, and the image he coins for it, of planes coming in to land, is perfect:

They used to stack up,

waiting in the sky

a long perspective of receding lights

out of the blackness,

coming in to land.

Stare at the dark for long enough,

you’d find

a star detach itself and float to earth.

And always more to come.

But that was then

Tying it to one kind of desire, the urge to write, with that title not only looks unnecessarily histrionic but detracts from the universality of the powerful ending:

Without knowing why,

I find this better:

silence after sound,

and solitude after society,

simply to walk out on the empty field,

feeling the wind across the open land,

expecting nothing from the empty sky.

Davies uses both rhyme and metre most skilfully, but there’s no denying that to some eyes and ears, they may give poetry a formal feel in more than one sense, and some readers react against that. Personally I rather like the classical vibe of epigrams like “A Marriage” – the title is from an R S Thomas poem on the death of his wife, and this clearly alludes to it:

For thirty years she loved him, or she tried,

but what she gave him, without price or pride,

was just a hazel staff cut from a hedge

that at the journey’s end is set aside.

And being myself a fan of Frost, I find the echo of his wry elegance ideally suited to the description of a sort of informal poetry event (“Centenary Square, Birmingham”)

It seemed, I thought, a special ring of Hell,

reserved, perhaps, for those who’d used their wit

to hurt, not heal, and sentenced for all time,

to bawl banalities through broken mics

with no-one there to hear, no audience,

except unsympathetic passers-by

to witness that they had no audience.

Now and again, I think he could trust the reader more. I didn’t need the photos that accompany some poems, and there are a couple of poem endings that seem too keen to tidy things up and press home a point already made, particularly “Speedway Eddie”, where to my mind the ending

I’m not so sure. From what I’ve heard

he never was a racer, just a fan.

Maybe we need to think that tragedy

must be the only way to break a man

could do very well without the last two lines. The poems about loss of faith, a recurring theme in this collection, don’t suffer from this; their uncertainty seems to have defied tidying up and gives them a fruitful ambiguity.

Another recurring theme is the poet’s Welsh identity, and indeed some poems here were originally written in Welsh and are the poet’s own translations, he being one of those enviable souls who are truly bilingual. But the two poems “A Welsh Prayer” and “A Welsh Blessing” are, surely by design, anything but intrinsically Welsh; they could refer to absolutely any country and the message of both is “be ready /to answer for this corner of the earth”. Davies is not an overtly “ecological” poet, but behind most of what he writes is a sense of the spirit of his surroundings, an urge to find “a better way to share this land, this light”.

July 8, 2024

Review of Culhwch and Olwen, by Catherine Fisher, pub. Graffeg Ltd, 2024

“Every tale has another chapter”

In her blog at https://www.catherine-fisher.com/culhwch-and-olwen/, Catherine Fisher explains what drew her to this particular Welsh legend and made her want to write a version of it for today’s children: “Culhwch and Olwen is not one story, but many different tales, held inside a framework. It’s a heap, a tapestry, a tangle, a hedgerow of stories”.

It begins, in fact, with a noblewoman giving birth in a pigsty because she has fled her home for reasons not plain even to her, never mind anyone else, and which would clearly make a story of their own; it ends with a young man and his wife returning to a court where it is hard to imagine him being safe, let alone happy. Along the way, there are all manner of other stories peering round corners and asking to be investigated, and some are, taking the reader down various byways, but others are tantalisingly unexplored: what became of the kind swineherd; who was Tywyllych’s dead husband; where did the great boar end up?

Being a writer very much disinclined to talk down to children, Fisher does not minimise the harsh elements of the tale: the pain of childbirth, the grief of an early death, the animosity bred in individuals by war and conquest, the clash of generations. But she does show how love, friendship, generosity and gratitude can mitigate these. Her favourite character in this huge galaxy is the Arthurian knight Cai – prickly, arrogant, dangerous – for whom she has shown a partiality in other books, but my favourite was a lame though determined ant. It will be no surprise to those who know her as a poet that she is adept at conveying the lyrical side of the story, but for any adults not acquainted with the hard edge of her YA novels, here are Cai and Bedwyr fulfilling one of Culhwch’s tasks by making a leash for the hound Drudwyn. It must be made from the beard-hairs of the fearsome Dillus, and these must be plucked while he is still alive. Fortunately, he happens to be asleep and drunk when they find him:

“Cai took a spade from his horse and began to dig. He dug a deep narrow pit and rolled Dillus into it, upright, and filled in the earth and trampled it down so that only the man’s sleeping head remained above ground.

“Tweezers”, he said. Bedwyr handed them over.

Cai crouched and plucked out a hair from the bristly black beard. Dillus gave a yell of pain and his eyes snapped open. He wriggled and struggled.

But he was buried deep.

Swiftly Cai plucked strand after strand of the beard and gave them to Bedwyr, who was already weaving and plaiting them into a leash.

But the huge man’s struggles were causing earthquakes and tremors. The whole mountaintop was shaking. “When I get out of here,” he roared, “you are DEAD!” Cai kept plucking. Suddenly Dillus roared out and one arm came free. Then the other.

“Look out!” Bedwyr leaped back.

“Do we have enough?” Cai snapped.

“Yes! Yes! Plenty.”

“Good. Then he doesn’t have to stay alive any more.” Cai stood up. With one slice of his sword he took off the man’s head,

Then he turned and walked away.

In the blog, she regrets having to play down the “list” feature so typical of these legends, though she does manage to echo it in one of the poems scattered through the narrative. But given the intended audience, I don’t think she could have done otherwise; most young readers would be unwilling to accept such long pauses in a story full of incident and narrative drive. She uses the poems to echo points where the original narrative is “written in a heightened prose” and to change the pace. They can also serve to see the story from a different angle, rather as Kipling uses poems to comment on short stories, and the first poem, “The Priest Tends the Grave” is a fine example of this. Prince Cilydd has assured his wife Goleuddydd, dying in childbirth, that he will never remarry. She, rating this promise at its true value and not wanting her son to have a stepmother, makes Cilydd vow to remarry only when he sees a bramble growing on her grave; then, unbeknown to him, she lays a duty on the priest attending her to weed the grave. Only after the old man’s death does the bramble grow:

He's busy. Gets there late on an autumn evening.

There are shoots. On his neck her angry breathing.

A decade of dandelion, nettle-sting,

He has grey hair now. His hands, uprooting.

Who can stop this green life? It just comes.

A dead queen torments his dreams

.

Boys play on the graveyard wall. His knees hurt.

Thorns tangle around his heart

.

He’ll be as cold as her next winter.

Every tale has another chapter.

Several of the story’s themes are miraculously condensed here, notably the attempts of the old and dead to control the young and alive, and the resurgence of life against all odds. Like all Catherine Fisher’s books for children and young adults, this has plenty to interest older readers as well.

June 16, 2024

Review of Cole the Magnificent, by Tony Williams, pub. Salt Publishing 2023

“So Gaddi began to describe the imagination. He said that it was a lawless place much given to extremes of weather. It was extensive and offered vast opportunities for conquest but most people’s visits there were concentrated in a small number of dismal slums. Its inhabitants seemed more beautiful and more virtuous than those in the real world, but were not to be trusted.”

I’m tempted to describe this novel as a compendium of all the folk tale motifs to be found in the world. Certainly it would be hard to assign to a genre. It begins in the manner of an Icelandic saga:

“The sheep parted as the riders approached, but a shepherd stood at the head of the track and barred their way. He said no guests were expected at Harald’s place that day. Brand said, ‘I have come to give Harald something which every man receives in the end.’ The shepherd replied, ‘You will not go down to give Harald his gift as long as I am standing here.’”

Far away though, in an Eastern city, another story is unfolding in Arabian Nights style:

“She learned that the city’s thirty-eight aqueducts were all designed by different architects, and that the waters they carried, all minutely different in mineral composition, were each named after their author: Jacob’s-water sat heavy in the mouth; al-Shatir’s-water was sweet as apricots; Musa’s-water dried the throat as if it were sand; Oswaldt’s-water tasted refreshing but smelled of eggs; Vlad’s-water petrified conduits, ewers, goblets, tongues; and Nahid’s-water burst forth like a hibiscus and trickled with the sound of her murmured reproaches.”

While on the road that leads from one to another, the relic-peddler Islip invents legends of more and more unlikely saints:

“Whether he was tailoring the story to suit his audience, or simply keeping himself amused, was not clear. Thus he gave to a minor jarl the heel of Saint Huberic, who was smothered by heathens but continued to preach to them for six days after he was dead. He gave to a rich widow the jawbone of St Anna, who refused to lie with a housecarl even though he kept her in gaol and starved her, and eventually turned into a summer greensward so that when he opened up her cell he was met by a million bright petals, and the waft of flower scent, and a swarm of midges.”

And at regular intervals in each story, we are reminded that most stories exist in many versions, none of which is definitive:

“Abulcasis says they travelled for a hundred years without a single minute going by. Edith of Malmesbury agrees it was a century, but says that the Cole who set out was the great-grandfather of the Cole who finished the tale. Ouyang Xiu says nothing about how long they rambled for, and instead gives at this point a recipe for stewed hare. But Walafrid Strabo, the most reliable of sources and also the dullest, estimates that the Men Without Bonds travelled about a half a dozen years in this aimless fashion.”

Some readers may be reminded at this point of The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, in which one tale continually spins off from another. But to my mind this is far more readable. I gave up on The Manuscript Found in Saragossa because its cast of thousands got too much for me. I do get what Potocki was doing: he was imitating the real world, in which everyone we meet has their own story, which in turn depends on many others, and which we can never hope to know in full. But the continual nesting of narrative killed the momentum. Cole the Magnificent is a “journey” story, amongst other things; for most of the time Cole is on his way from his past to an unknown future, and even when his physical travels are over, “Niven could see that his gaze was not on the steading and the work at hand, but on an inward landscape and a journey to the time of long ago”. This gives it enough momentum to withstand the constant digressions.

In fact, where Potocki replicates the structure of real life, Cole the Magnificent replicates that of story, which is frankly more interesting. Some of its humour is that of fantasy and hyperbole; “By now King Egg was so great that he had been divided into parishes. His left leg was stretching in spring sunlight while his right arm was still snoring in the depths of winter. If a man walked round him with a basket of cherries he was liable for a customs charge.” At other times the humour recalls rather the laconic style of saga, as in the unfailing sarcasm of Sigrid’s edgy relationship with Saul:

“The next morning Sigrid was put on a mule with her things, and Saul took up the reins to lead it. ‘I hope you will not think yourself a princess just because you are saved the effort of walking,’ said Saul. ‘I hope you will not think yourself the master just because you hold the reins,’ said Sigrid.”

Yet when Saul feels his death coming on, the same dry, laconic style can be, as it often is in saga, powerfully moving:

“‘It looks like I will be leaving the steading earlier than we thought,’ he said. ‘Will you sing a charm over me so that my farewell is not lonely?’ Sigrid said that matters were not that bad, but if things took a turn for the worse then she would do as he asked. ‘It would be the first time for that,’ said Saul.”

The end of the book at first seems to offer the obvious explanation that “story” is fantasy dreamed up by its creators:

“But Mariana of Warburg asserts that Cole, ‘an old Breton king much given to laziness,’ sat down on a bundle of withies and fell asleep. He dreamed the lives of Sigrid and Niven, Svinkeld and Ludo, Colrick and Gaddin, and while he dreamed his body caught light and burned in the green flames of summer; and his ashes drift down to earth every year as dandelion seeds.”

But we have already, much earlier, been given a strong hint that story can be, or become, more real than this:

“‘Imagine that you and I were to sit here on this terrace forever, talking of astronomy and eating oranges, with no yesterday and no tomorrow, only you and I forever in this conversation.’ Niven thought about this for a long moment, and felt what Gaddi had said actually beginning to happen. Birdsong filled the shade under the trees. There were – three, four, five, six – oranges in the bowl. A bead of condensation clung to the jug. The birdsong went on, and Niven and Gaddi sat in silence as the moment lengthened. There was a spasm of eternity.”

This is an absorbing, entertaining read with a lot to say about the relationship between reality and imagination and the nature of story.

June 1, 2024

Review of Glorious Exploits, by Ferdia Lennon, pub. Fig Tree 2024

Gelon says that’s what the best plays do. If they’re true enough, you’ll recognize it even if it all seems mad at first, and this is why we give a shit about Troy, though for all we know, it was just some dream of Homer’s, and I walk towards this green soul river, and for a moment it’s like I’m going home.

412 BC, and the surviving Athenian prisoners from the disastrous Sicilian Expedition are starving in the quarries of Syracuse. Our narrator is Lampo, a young Syracusan potter like his best friend Gelon. But Gelon is also a fan of the theatre, particularly of the Athenian playwright Euripides, and he conceives a fantastic plan; he and Lampo, using the prisoners as actors, will stage two plays, the Medea and The Women of Troy, in the quarry itself.

‘That’s why we have to do it,’ Gelon says with feeling. ‘You’re right, they’re doomed, and in a few months, they’ll be gone. With the war, it might be years before we ever see another Athenian play in Syracuse. Some people are saying when Athens falls, and it has to fall, the Spartans will just burn it to the ground. There might never be another Athenian play again!’ The cup cracks in his hand, and the wine splashes on the ground. ‘For all we know, those in the quarries are all that’s left of Athenian theatre, at least as far as Syracuse is concerned.’ He stops and looks down at his arm where he cut himself, scanning it intensely as if the words he needed might be found there. ‘And it’s not just Medea. The Athenians told me that before they left Athens, Euripides wrote a new play. A play about Troy. About the women at Troy after it’s fallen. No one’s seen it in Sicily. It’s a whole new Euripides. And we’re going to do them both. Do Medea, and The Trojan Women. See, we can’t let them disappear. We have to –’ ‘Have to what?’ says Alekto, her voice gentler. ‘Keep them alive and put on the play.’

These two plays have been carefully chosen to make the novel’s point. Both illustrate a constant theme in Euripides: how suffering can either ennoble people or degrade them to brutes, depending on character and circumstance. Medea is cruelly treated and driven by anger, loss and bitterness to commit an atrocity in her turn. In Women of Troy, Hekabe, whose suffering is even greater, manages somehow to rise above it and even to find one source of comfort:

“Yet, had not heaven cast down our greatness and engulfed

All in the earth’s depths, Troy would be a name unknown,

Our agony unrecorded, and those songs unsung

Which we shall give to poets of a future age.” (Trs. Philip Vellacott)

Gelon echoes this when encouraging his ragged, shackled cast:

“How many will come? I can’t say, but we’ll know soon enough. I believe you’re going to show them something they’ll never forget. When they leave here later today, the few or many will be changed, and whatever happens in the future, Athens will be remembered, and you will be a part of that remembrance.” (This speech, incidentally, is the only reason I can think of why Hekabe is, throughout the novel, called by the Latin form of her name, which Euripides did not use; maybe Lennon wanted the echo of “What’s Hecuba to him?”)

Syracusans have good reason to hate the Athenians, and many who have lost kin to the war still do. But when in the second play the “dead” body of the child Astyanax is brought onstage, Lampo sees a strange thing happen: “I can hear sobbing now. Fishermen with faces craggy as the quarry rocks are snivelling. Aristos too. Even the prisoners weep. It’s the maddest thing. ’Cause for the briefest moment, Syracusans and Athenians have blended into a single chorus of grief for this make-believe.”

The power of fiction is real, and believable here, the more so as it is not exaggerated. There are people too low, too ignorant and too plain mean to be uplifted by it. But when it does work, it is transcendent, as when a border guard who saw the play shows mercy to his enemies: “Gelon frowns, but it’s like the guard’s lantern has left a bit of its light in Gelon’s eyes; his cheeks, though still dark and bruised, are brighter than before”. And Lampo, inexpertly playing an aulos, makes a comparison with the rats in the quarry:

“of course, you couldn’t really call what I’m doing playing – but it clashes with the scurrying of rats, their awful screeching, and in my mind, those rats aren’t just rats, they’re everything in the world that’s broken. They’re things falling apart, and the part of you that wants them to. They’re the Athenians burning Hyccara, and the Syracusans chucking those Athenians into the quarry. Those rats are the worst of everything under an indifferent sky, but the sound coming from the aulos, frail as it might be in comparison, well, that’s us, I say to myself, that’s us giving it a go, it’s us building shit, and singing songs, and cooking food, it’s kisses, and stories told over a winter fire, it’s decency.”

It will be clear by now that the Syracusans of the novel speak with distinct Dublin accents – and why not; Sicily is after all an island both menaced and attracted by a stronger mainland culture. Anyway it works; “’How do we promote this?’ ‘We tell people.’ ‘Grand so.’ And like that, we get stuck into promotion.” It also now and then enables Lampo to give a curiously contemporary feel to the proceedings:

“There are a few aristos in the corner, rolling dice and making too much noise. Their cloaks are the brightest things in the bar, and their perfume blends with the odours of fish and fresh paint, and the result is something weird and new. I don’t like it. Sure, Dismas’ was a kip, but it was our kip. Too much money’s flooding into this city, and it’s losing something, though perhaps that’s just what a man feels when he can’t see what he’s won. Thirty years of age, and I live with my ma. Not what I’d planned for.”

This is a powerfully moving, sometimes exhilarating novel. It is also intermittently funny, because our narrator has a wry way of seeing and phrasing things – “I fancy some Catanian, but I know Lyra doesn’t like red, so I also grab an Italian white the vintner says is ‘causing quite the stir’. It certainly causes a stir in my pockets, for a great deal of coin leaps up and out of them at purchase.” Many reviews I’ve seen seem to stress this angle, which I think is a mistake, for at root this novel’s theme is deadly serious; namely how art can uplift people and make them want to be something more than they are. It’s certainly the most moving and impressive novel I have read since George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo.

The novel’s coda echoes what must have been the inspiration behind it; the story in Plutarch that some Athenian prisoners managed to escape and reach home because they could recite Euripides to the theatre-mad Syracusans. The last word is with that playwright’s major-domo, who reflects that “his master was ever in love with misfortune and believed the world a wounded thing that can only be healed by story”.

May 16, 2024

Review of Iktsuarpok, by Nora Nadjarian, pub. Broken Sleep Books 2023

A short journey, before doors slide open and they empty into their lives (“Clay Animation”)

The above line, ending a poem in which the poet speculates about fellow-passengers on the Tube, is a good place to start thinking about these poems. Nearly all are short vignettes, moments, transient but deeply experienced states of being. The title poem, indeed, centres on an Inuit word that describes the state of impatient excitement one gets into while awaiting a longed-for visitor. “I found the word which/starts here and ends when you arrive.” The weird thing is, the poem leaves one feeling that however welcome this visit (and this is a poet who seems, at least in these poems, delightfully and unusually at ease in relationships), it cannot possibly be as enjoyable as this state that precedes it.

Poets who work in a small compass are considerably helped if they happen to be good at coining memorable phrases. It’s a gift that can become a curse if overdone, turning poems into a collection of soundbites, but here it is well used, sometimes as a perfect shorthand for a state of mind (“the sound of listening to nothing at night”), sometimes to provide a close that echoes in the mind, like the ending of “The coast guard found an empty life raft”:

The coastline called us back.

Throw out everything you own, lose weight.

I tipped all my words overboard,

Lastly, the unreliable narrator.

There are many references to exile and war in these poems, not surprisingly since the poet’s Armenian grandparents fled Turkey for obvious reasons at the start of the twentieth century and settled in Cyprus. Nadjarian, born in 1966, was the second Cypriot-born generation in her family, but then of course politics and divisiveness caught up with them in their new location and the poet ended up being educated in England (she later returned to Cyprus and now lives in Nicosia). I’m mildly puzzled, by the way, by the dust-jacket’s description of this as a “first collection”, because I know there’s been at least one other (Cleft in Twain, 2003), and thought there were more. The violence of the war imagery, e.g. “a country is being chainsawed”, from “We didn’t die, we levitated”, spills over into poems on other themes, like “Downpour”, which ends “still killing us, this rain, with its bullets”. There are also poems that reference relationship break-ups, and a pervading sense of mortality:

We were once human and to human

we may never return

(“Thirteen Ways of Looking at Uncertainty”)

In view of all this, it is perhaps odd that the overriding impression the collection left with me was one of colour and light, joy, even. I think this is partly because of the vividness of her observation and description which, in defiance of the dictum about happiness writing white, actually seems to work best on that theme. “Hibiscus” is by far the most successful and sensual evocation of sexual climax from a female point of view that I have ever read, and in “The Perfect Child Emerges”, she lifts the everyday mentions of “sucking and sobbing” and “shiny new teeth” with a beautifully oblique allusion to the myth of Apollo’s birth and brief infancy:

Then, with incredible speed away from you, a tall boy runs from one season to the next. Away from this baby in the cot sucking its thumb, oblivious to the sudden earth, the endless sky.

Nuts to Larkin; this is how to use the “myth-kitty” to universalise personal experience.

May 1, 2024

Review of My Body Can House Two Hearts, by Hanan Issa, pub. Burning Eye, 2024

I am a woman of neither here nor there (“Lands of Mine”)

This is a first collection of 20 poems by a poet of mixed heritage from Wales. I was attracted to it partly because I lived many years in Cardiff and partly because I have a weakness for poets who don’t quite come from any one place, either because they are deracinated or because their roots are various – “lands of mine”, rather than the singular “land”, to quote the first poem’s title – and who, as a result, often don’t have a comfort zone.

The poems reflect the problematic elements in both sides of her ancestry. Her Welsh “nan” is the archetypal supportive Valleys grandmother, but Wales is also where, during the poet’s childhood, she has been racially insulted and regarded as “different”. This can lead to embracing more fervently the other half of one’s identity, but that too is not so simple, perhaps especially for a woman who has grown up in a culture that pays at least lip service to female equality:

‘Please, sister, stand on this pedestal just below me.’

‘But brother, paradise lies at my mother’s feet, not yours.’ (“Qawwam”)

Rather than choose one over the other, she decides that “finding the space in between/was the goal” (“I Don’t See Colour”) and several poems do in fact focus on connexions, likenesses between her “two lands”, which are not hard to find. In “Beauty and Blood” she likens Capel Celyn, flooded for a reservoir to send water to Liverpool, to the Hammar Marshes, drained by Saddam in his war with the Marsh Arabs:

Imagine they drained the Hammar

to flood Capel Celyn: an exchange of tears

displacing people like chessboard pawns.

Part the whispering reeds’ soft curls

and watch smatterings of life drift lost.

As the little Welsh town fills with water,

hear the pained goodbyes of women

who tattoo each other’s stories in secret.

This does a good job of reminding the reader that the terms “us” and “them” properly apply to ordinary folk all over the world (“us”) and those in power (“them”) who regularly mess up our lives. Sometimes her language is less powerful, because in her drive to convince, she forsakes the poetic for the didactic. For me at least, “Croesawgar”, though it has its moments, is more of a political lecture than a poem, all rhetoric and no music. This urge to convince is something most poets need time and a lot of practice to learn to control; it comes with increasing confidence in one’s own voice, so that the words on the page no longer feel they have to shout to get their point across.

This is a lively, promising collection, mostly in free verse but with some experiments in shape and a couple of rhyme poems, of which the ghazal “Paradise for Poets” is handled so well that I hope she will experiment with more of them. The final poem “Watching him eat strawberries”, about her small son, ends with a verse that repeats a significant phrase:

But I want to stay here,

with his dirt-filled fingernails,

juice trickling down that little chin.

Wallahi, I want to stay here.

Clearly in this context, “here” is not a place but a situation, a way of being; she wants to stay in the moment. And she knows, of course, that this is impossible; there is no staying anywhere or anywhen. But then if there were, we would have far fewer poems.

April 16, 2024

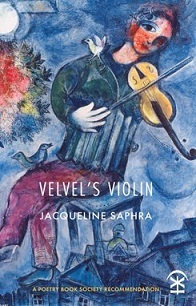

Review of Velvel’s Violin, by Jacqueline Saphra, pub. Nine Arches 2023

We did not want enough

to do the merciful thing. – “Mercy”

The poet has remarked that this themed collection “is about our common humanity”. That is true, inasmuch as all human suffering touches all humans. And there are near-explicit references to contemporary events, like the proposal to export refugees to Rwanda, glanced at in “Madagascar”. But the collection is very much written from the viewpoint of the particular, Jewish, group of humans whose history is hers, and who certainly have a great deal of human suffering to draw on. “Mercy”, the poem quoted above, is one of the few that is from a more general viewpoint and is indeed about the suffering of a bird rather than a human. And in some ways it’s an odd one, because the “merciful thing” that the crowd of anonymous people cannot bring themselves to do would, in this case, be to kill the bird, which is too injured to live. It would be somewhat alarming to see this as a direct analogy for the human condition, but I think the point is that “mercy” is not always easy and that we often, like this crowd, continue on our way rather than get involved.

In the poem “Jew”, the main speaker lists a mélange of facts, slanders, myths, cliches, symbols – “the Nobel and the intellect, the where, where, not here, diaspora, the klezmer, mazeltov, the shabbos bride, the candlestick, the yiddishkeit, the pogrom” – while a subsidiary voice keeps interjecting with comments like “don’t dwell on that again” and “no no, move on, move on”. Since this voice is in italics, it could well be the internal voice of the poem’s speaker, anxious as to how it will come over. But it echoes the spoken and unspoken response that accounts of suffering often generate, especially from those who have been either responsible or complicit in it. Those who have come out on the “winning” side of any conflict routinely want the losers or sufferers to “move on” and forget their resentment; we see the same response in many situations, vindicating the poet’s claim to universality. In a much less extreme example, the recent anniversary of the miners’ strike led some to protest to the BBC that rather than watch programmes about it, we should all “move on”, in reply to which an ex-miner pointed out that he was in effect being asked to move on from his own history.

Saphra is eloquent on the impossibility of this in “The Trains, Again”:

again the trains, it is this friend whose mother told her

That is the tree, that is the tree

– as she chopped the onions, stirred the soup

bleached the bleachable, celebrated the spring:

When they come for us, I will hang myself from that tree.

When will they come for us, my friend?

Can you hear the trains? I hear them

in my sleep, rattling continents, heaving

and breathing along the tracks of my veins

riding my blood. There is no silencing them.

I tend to think of Saphra as a form poet, and though there is more free verse here than I generally associate with her, there are also sonnets, a ghazal and, in several poems that look at first sight like unrhymed couplets, subtle patterns of rhyme, half-rhyme and assonance lurking under the surface, eg in “Poland, 1885”, where the rhymes and near-rhymes cross the couplet breaks:

a past I sought long overgrown

the state of currency still volatile

human traces vague, all guesses wild.

Nothing left to find; nothing and no-one.

But oh, the language: soft-tongued

apologetic; those legends of tracks

pointing towards infinity; haystacks,

horse-drawn carts; disappearing villages

There’s no denying that, like all themed collections, this does harp a lot on one string, which is not everyone’s fancy in a collection. But towards the end, there is a note of redemption being sounded. It seems, in “20264” and “The News and the Blackbird”, to be intimately connected to birth and motherhood, and the second of these poems is particularly noticeable for the return of the bird motif, this time in a happier context. The blackbird “will not stop her song” and, when the narrator is obsessed with war the bird bursts out “suddenly in the key/of joy Look out! Look up! The stress on the bird’s femaleness is interesting; female blackbirds sing far less than males, more quietly and only in the breeding season. This one has a “chick-heavy” nest, the presumable cause of her outburst of joy. There is a parallel here with another recent collection I’ve lately read, Nora Nadjarian’s “Iktsuarpok”, which also has a background in war (Cyprus) and persecution (the Armenian genocide) and which also sees redemption and joy in human, particularly parental, relationships. Indeed the ghazal mentioned earlier, “Before the War”, is addressed to Nadjarian, and wryly encapsulates the universal, ongoing human condition of which both poets speak:

Now truth drags out its death drawl: ‘To which current war do you refer?’

We live in the dark of that question: no such era as ‘before the war’.