Sheenagh Pugh's Blog, page 11

January 16, 2022

Review of Where the Birds Sing Our Names ed. Tony Curtis, pub. Seren 2021

This is an anthology of poems published in aid of Ty Hafan, a hospice for terminally ill children in South Wales. All proceeds from sales go to the hospice; the publisher and contributors gave their work gratis. These contributors include several big names – George Szirtes, Philip Gross, Tamar Yoseloff, Rowan Williams and Pascale Petit among others, and a few poems are, fittingly, in Welsh. They also include one of mine, but as usual I have decided I can reasonably review the rest of the anthology.

The poems are themed around childhood and parenting. There is an introduction by Tony Curtis in which he outlines how the anthology came about, and one by the director of Ty Hafan in which she explains its remit. There’s also a third, which might seem like one too many, a foreword by Ilora Finlay which I think might be unintentionally misleading. Many poetry fans would read phrases like “this beautiful gentle anthology” and “poems to bring calm warmth to the reader” with apprehension, fearing that they heralded acres of sentimental undemanding hygge – I knew this couldn’t be so, but only because I knew the work of many of the poets.

In fact most of these poems are by no means “gentle”, nor aimed at providing warm fuzzies – how could they be, with such a powerful and challenging theme? Some of the children in these poems were wanted but never born; some died young or became estranged from their parents. Even in the happiest cases, children grow up and leave, while parents don’t live for ever – one of the most powerful poems here, or indeed in existence, is the late Emyr Humphreys’ “From Father to Son” with its almost unbearably moving vision of a dead father:

There is no limit to the number of times

Your father can come to life, and he is as tender as ever he was

And as poor, his overcoat buttoned to the throat,

His face blue from the wind that always blows in the outer darkness

The anthology is in three sections; the first concerns conception (or failure to conceive), birth and infancy. In this section, poems that particularly struck me were Zoe Brigley’s “Name Poem”, about the feelings of would-be parents who go home empty-handed

and intimate as a gun to the temple:

your name sounds the trigger click

and George Szirtes in his most playful and joyous mode for “New Borns”:

What child with foreknowledge would enter the world?

I would, said Geraldine,

For gooseberries, geckos, goldfinches, gorgonzola,

I would enter the world.

There’s a whole alphabet of this, and knowing that among the names are those of the poet’s grandchildren somehow adds to its delight.

The second section concerns childhood and schooldays, and the standouts here for me were Jude Brigley’s rueful musings on why children seem to recall the times one failed as a parent better than the times when one succeeded (and how appropriate that this anthology should contain poems by a mother and daughter!), John Barnie’s “Standing By”, with its perfectly judged rhythms that make one want to read it aloud, and above all, Paul Henry’s spare, taut “The Nettle Race”, short enough to quote in full:

Tilting into the garden wall

three boys’ bicycles,

frieze of an abandoned race.

Briars cover the chains,

their absent riders’ chins.

The tortoise rust won with ease.

Slowly the sun leans

towards its finishing line.

In the last section, focusing on increasing distance between child and parent, the scope widens and we hear, through the words of writers like Abeer Ameer, Lawrence Sail and Jo Mazelis, the voices and concerns of the displaced and endangered elsewhere in the world. In Sail’s “Childermas” the hand-holding gesture of two refugee children becomes iconic, universal:

They are following the bent backs

of grown-ups with bikes and bundles, heading

for Cox’s Bazar; as always, they are holding hands.

The last time they surfaced was in northern France, at the tail

of a struggling queue on a beach.

They were waiting to board an already laden

black rubber boat – and holding hands, as always.

There are many fine, powerful poems in this anthology, and plenty of reason to buy it even without the impetus of a good cause. It can be ordered direct from Ty Hafan

January 5, 2022

List of reviews for 2021

The usual list with links, for anyone who’d like it. 23 reviews last year, and one author interview.

Author interview

Poetry collections

The Magpie Almanack: Simon Williams, pub Dempsey & Windle

Inhale/Exile: Abeer Ameer, pub. Seren

Still: Christopher Meredith, pub. Seren

Terminarchy: Angela France, pub. Nine Arches

The European Eel: Steve Ely, pub. Longbarrow Press

Utøya Thereafter: Harry Man and Endre Ruset, pub. Hercules Editions

in the coming of winter: Frank Dullaghan, pub. Cinnamon l

Anthologies etc

Broken Lights: Basil Ramsay Anderson, ed, Robert Alan Jamieson, pub. Northus Shetland Classics

100Poems to Save the Earth: eds Zoe Brigley and Kristian Evans, pub. Seren

100 Poets: A Little Anthology: ed John Carey, pub. Yale University Press

Beyond the Swelkie, celebrating the centenary of George Mackay Brown: eds Mackintosh/Philippou, pub. Tippermuir

Prose fiction

The Tall Owl And Other Stories by Colum Sanson-Regan, pub. Wordcatcher Publishing

Hello Friend We Missed You: Richard Owain Roberts, pub. Parthian

Please: Christopher Meredith, pub. Seren

Tang: J J Haldane Burgess, reprinted by Shetland Northus Classics

Foreign Bodies: David Wishart, pub. Severn House

This Much Huxley Knows: Gail Aldwin, pub. Black Rose Writing

The Red Gloves and other stories: Catherine Fisher, pub. Firefly

Trade Secrets: David Wishart, pub. Severn House oves and other stories

Non-fiction

I Don’t Want To Go To The Taj Mahal: Charlie Hill, pub. Repeater Books

Burning the Books: Richard Ovenden, pub. John Murray

Ancestors: Prehistory of Britain in Seven Burials: Alice Roberts, pub. Simon & Schuster

Cave Beck: The Universal Character, prepared with foreword by Andrew Drummond, pub 2020

December 31, 2021

Review of Darkness in the City of Light by Tony Curtis, pub. Seren 2021

“Perhaps we will come through this present madness and the cafés, the Seine, the Sorbonne and the Louvre will be here as always and the city will be reclaimed by us again.”

The first thing to note about this novel is that the protagonist is not really any one person but rather the city of Paris itself at a certain time in its history; in this it is in the tradition of novels like Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer. It also resembles that novel in using several different narrative methods: diaries, letters, court reports, poems, newspaper articles, official posters, even photographs.

Some of the various voices will be familiar from other contexts: Picasso, keeping his head down in his apartment and painting carefully noncommittal still-lifes, Max Jacob, appealing to his friends for help that doesn’t come, Albert Camus, editing a Resistance paper, Ernst Jünger, a civilised man trying, unforgivably, to close his eyes and ears to barbarity, Hemingway, swaggering drunkenly through the Liberation unaware of how those who actually accomplished it are laughing at him behind his back. Others don’t speak but appear in memorable vignettes, like Fred Astaire tap-dancing down the Place Vendôme. The person the back cover concentrates on is the serial killer Maurice Petiot, who preyed on people wanting to escape the Nazis and murdered them for their possessions. But actually he does not dominate most of the novel any more than the others, which is just as well because, like many intrinsically evil people, he’s actually a bit of a bore, banal and predictable. I don’t doubt this portrayal of him is accurate enough, I just didn’t find him as interesting to read about as more equivocal, many-sided characters like Jünger and Picasso.

Their voices, and indeed the voices in general, are very well differentiated and convincing; the only conversation that didn’t quite ring true for me was a brief one between two GIs, “Jimmy” and “Sid”. But the character they are all working to build up is that of the city itself. This, as one would expect, is seldom black and white; it is clear, for instance, that some of the Resistance fighters, after the Liberation, behaved as thuggishly as the Milice did during the war. And some of the erstwhile conquerors, shorn of their authority, look, even to the recently oppressed, like what they are:

“And at the tail of this long rat procession, a few stragglers, some limping, some unsteady, with vacant faces and making their way through their own dream. And then scattered among them some so young that they seemed like schoolboys. Some with their hands behind their heads. One kid with his head slumped down against the back of the fellow in front, not looking or taking anything in. What was he thinking of – his mother, his home? What was he remembering? A few days ago, I thought, I could have slit his throat.”

Perhaps the strangest thing, though utterly convincing, is the consciousness that all this will be absorbed into the city’s history, like so much before:

“One morning when I went out in search of food within a short walk of our apartement I saw young boys and old men fishing in the Seine in the sunshine as if nothing was amiss. Some other boys dived from the bank and swam. This could be a painting by Seurat or Monet.”

This is an unusually structured novel with a lot of intrinsic interest, though for me, it does not in fact centre around Petiot, but around Paris.

December 16, 2021

Review of Trade Secrets by David Wishart, pub Severn House 2015

“It was well into the afternoon when I rolled back in, by which time the poetry gang had usually dispersed to their respective homes, leaving the Corvinus household a blessedly poetry-free zone.

Only this time, as it transpired when I came into the atrium holding my customary welcome-home wine cup, they hadn’t. There was one of them left.

Bugger.”

Not only has Corvinus, despite staying in the wine-shop all afternoon, failed to avoid all Perilla’s poetry pals, this one has a murder for him to solve; her businessman brother has been found dead. And as if that weren’t enough, Marilla and Clarus, visiting from Castrimoenium, come home excited at having all but witnessed a second murder…

So Corvinus has two to solve at once, and the question is one of motive. Gaius, the brother of Perilla’s friend, was a legitimate trader but also a ladies’ man who had infuriated at least three husbands, not to mention his own wife, while Correllius, the victim Marilla and Clarus found, was a distinctly dodgy import-exporter with many business enemies. But is the question of motive in each case as simple as it looks? And might there even be a connection?

This one is set partly in Rome, partly in Ostia; we meet Lippillus, who has been transferred to a new district, and prickly next-door neighbour Petillius, who has another spat with the Corvinus menage. The detective work itself involves making connections between seemingly unrelated events and people, and is as fascinating as ever. There’s also a sense of our protagonists getting older; Corvinus is considering renting a holiday home by the sea and talking about wanting a quiet life, not that he is ever liable to get (or settle for) such a thing. One of the best features of this series is the convincing way it lets characters age and develop. But Corvinus’s bolshie chef Meton is still on his usual truculent form when explaining a fracas with next door’s cook:

“I was at Mama Silvia’s stall in the market like, buyin’ pears, and he, that’s that bastard Paullus, was standin’ behind in the queue. I says to Mama, “I’ll take some of them Dolabellans for a compote, love”, an’ Paullus says “Nah, you want Laterans for that”, then I turns round and says “Rubbish, Laterans ‘re too moist for a compote”, then he says “Moist? The way you cook, your lot wouldn’t notice if you used bloody Falernians”. So I picked up a melon and belted him with it.”

As I’ve explained before, these are catch-up reviews which I’ve done because I discovered that some Wishart fans were unaware of his changes of publisher and had missed a few. You're up to date now, and can keep up with future events at his website https://www.david-wishart.co.uk/

December 1, 2021

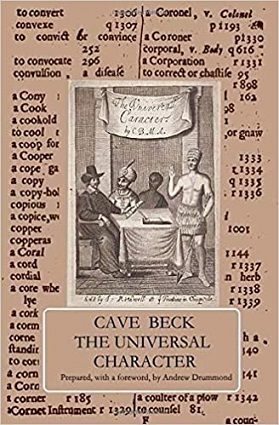

Review of “Cave Beck: The Universal Character”, prepared with foreword by Andrew Drummond, pub 2020

book cover

book cover Is Cave Beck perchance a stream in Yorkshire, sez you? No, sez I, he was an Ipswich schoolmaster who in 1657 published a scheme for a universal language. As those who have read Mr Drummond’s novel A Hand-Book of Volapük will be aware, he is hugely interested in universal languages. That novel was set in the late 19th century, when several were being invented at once; Beck lived in the 17th-century Enlightenment era when there had also been interest in the search for such a language, which its adherents fondly imagined would enable “all the Nations in the World to understand one another’s Conceptions”.

This book begins with an introduction by Drummond in which, with his usual dry humour, he enumerates several reasons why Beck’s idea did not take off. A profusion of typos in Beck’s work, plus a hopeless system of cross-referencing and indexing and an eccentric choice of vocabulary, rank high, though personally I would add another which Drummond doesn’t see as a problem in itself. Beck’s system was partly mathematical: he substitutes numbers for certain words (the “primitives” or radicals from which others can be formed) and uses letters to represent cases, persons and tenses. Thus, for instance, the verb “to see” is 480 – pronounced “forato”, for this was to be a spoken as well as a written language and Beck gives a pronunciation guide. Agent nouns are prefixed by “p” and feminines by “f”, so a woman who sees would be “pf480”, unless she’s in the accusative case, when she is “pif480”. “We will see” would be “ag480s (agforatos)” And so on…

The idea was, firstly, that words from any language could be transferred into this code (in fact it would only really work for European languages, and a French version of the book did come out in the same year) and secondly, that it would be easy to learn. Beck points out that Latin, though it was at the time something of a universal language for highly educated Europeans, took years to learn. He reckons a child of ten can learn his universal language in four months. I can only say that this child, and Beck himself, clearly don’t share my own numerophobia: as soon as I saw the system involved numbers as well as letters, I knew I could never learn it.

Nevertheless, his grammar does actually make sense in principle; what does not is his choice of root words, which goes by the alphabet; whichever comes first in the dictionary becomes the radical. This leads to nonsense like “made” being the radical and “make” having to refer back to it. The dictionary which takes up much of the book is however fascinating for what it shows about his priorities and those of his day. In contrast to the Junior Oxford dictionary, which culled numerous plant names a few years back, Beck names every herb and tree he can recall, including “cat’s-tail, a long round thing growing on nut-trees”. There are also a remarkable number of worms, including the hand-worme, the palmer worme (he doesn’t say if it sports a little cockleshell badge) and “a worme eating vines”.

This dictionary is in fact a wonderful time-wasting device; who wouldn’t want to know more about the lentish tree, the material Fillip & Cheyney, or the disease known as purples? To be a fan of the book as a whole you probably need a basic interest in linguistics, especially in the whole idea of invented languages. But for those of us who do, this is an essential little gem.

November 16, 2021

Review of "in the coming of winter" by Frank Dullaghan, pub. Cinnamon Press 2021

This is how we live in time.

This is how quickly it passes.

“How We live In Time”

Frank Dullaghan, here on his fifth full collection, is now a grandfather and increasingly conscious of which end of his life is nearest. Not necessarily in a brooding or gloomy way; more with the intellectual curiosity of a poet who has found a new subject that repays observation. And his observation is as sharp as ever, witness the start of the poem quoted above:

I have no vacation days left, but will travel

to see my new granddaughter. I shall have to pay

the days back. We are always robbing

our future as if it were endless,

paring days off it like butter for toast.

The shift from personal to universal in that third line, and the way the phrase “I shall have to pay the days back” potentially belongs to both, happens all through the collection and is handled very deftly. There is a great deal of personal detail, particularly about parents and other relatives who have died and who, as so often when one is growing older, can seem more present than the living. But these details never exclude the reader, because Dullaghan is adept at finding the universal in the particular. “Transparency” begins with an image of a man being eased out of a job:

Already, people have begun to look through me.

I have been moved to a smaller desk that is easily passed.

Strategy and future planning meetings are happy

with my absence. I no longer know what’s going on.

But it soon becomes apparent that this really is less a description of one person’s reality than a metaphor for something at once more nebulous and more cosmic:

Most evenings now, I check my shadow for solidity.

In some lights, it lacks substance, its grey cloth

dissolving like a tissue in water. The weekly journey

to my post office box is usually futile, I have begun

to avoid mirrors.

I think it was this technique which enabled the collection to overcome a pet prejudice of mine. I freely admit I normally dislike reading poems, or for that matter fiction, about covid. I feel it has made real life dull and irritating enough without invading the imagination as well. But though covid does figure in this collection (one could hardly expect otherwise, in a collection that must have been completed in 2020 and which is so concerned with mortality), it is not in any sense “about” the virus: covid is just one aspect of a wider theme, the fragility and impermanence of human life. In “The Lists of the Dead”, the lines

We name the ailments and vulnerabilities

of our siblings and offspring,

our distant friends

could be read in a covid context but also recall the conversation of many a remembered granny. And in “The Eyam Example” this wider view enables him to skewer the too easy, and too optimistic, comparison with the famous plague village whose sacrifice we remember, but not “the enforcing barricades, the cudgels”. Will a post-covid world be one with “more compassion” and fairer wealth distribution? Probably not…

In Eyam, the rich

escaped before the lockdown was enforced. The poor,

when it was over, were mostly dead.

Dullaghan has always had a gift for coining memorable phrases that feel somehow just right – “familiar streets arrive at wrong places”, a plane “runs towards the sky”, a beginning day “warms its engine”. Just occasionally, this knack fails him, usually when he is getting worked up about something, like politics; in some of the poems about Palestine and gun culture, his language, though passionate and forceful, is less forensic and more predictable. But for most of this collection, it is fascinating to watch a skilled practitioner with words getting to grips with the most basic theme of poetry, namely mortality, and trying out ways of approaching it, like

the way endings can feel like beginnings

if you come at them from the other direction

(“Flying South”)

and the end of “Crossing Over”:

maybe in the end it is the simplest thing.

Here, then not here. Over.

November 1, 2021

Review of Utøya Thereafter, by Harry Man and Endre Ruset, pub. Hercules Editions 2021

This is an extract from a longer work, “Deretter” (“thereafter”), written to commemorate the 69 victims of the murders on the island of Utøya, Norway, in 2011. The Norwegian work has 69 poems, one for each victim, plus “Prosjektil” (Projectile), a poem written by Ruset after the murderer’s trial and based on forensic evidence concerning the movement of bullets through the body. This pamphlet has a condensed version of that poem, in both Norwegian and English plus 25 of the 69, in English only.

The poems for the victims are written in the shape of faces, not very obviously so, but more so that the face suggests itself, resolving out of the words, as one reads. No two shapes are exactly alike; I don’t know if they were perhaps based on newspaper head-and-shoulders shots of the persons concerned, but they look as if they might be. Needless to say, this makes it quite hard to quote meaningfully from them, because the impact is carried in the overall shape on the page as well as the words. What one can say is that many are based on personal details, which, like the different face-shapes, individualise the subjects and bring them, often achingly, to life along with those who mourn their loss:

I don't want

to remember which

paving stones in the garden

you loved to tip up. To watch the

woodlice run in every direction.

Over and over, these poems emphasise what a gap each individual leaves, how impossible, yet inevitable, it seems for those bereaved to come to terms with a world that no longer contains him or her:

Julys feel like oceans.

You know they will rise and bring

new questions. What if and if only

Sometimes they seem to seek comfort in pantheism, imagining the dead becoming one with the island, part of the weather, the “grey/ light that peels back”. Other poems, though, admit more finality:

A face in the grass

Outside the entrance to the Café

Building. There are no gods, only

people. No words

to make the

dead rise again.

In contrast to the face-poems, “Projectile”, in the middle of the sequence, moves in a brutal straight line across the page, enumerating the body parts it passes through in a dispassionate tone that mirrors the way its subject dehumanises and denies the individuals it enters. (In the Norwegian version there is only one of these lines to a page, which emphasises still more the bullet’s momentum and trajectory. The pamphlet can’t allow itself this luxury and has several lines to a page, which is probably inevitable but does detract a bit from the effect, I think.)

Ruset and Man decided to leave out the victims’ names, and while I can see how the families might prefer this, in some ways I think it would have been apt to have them as titles for the poems. One name they are both, rightly, very careful to leave out, both from the poems and their foreword and afterword, is that of the perpetrator, and I was disappointed to see it mentioned several times in the introduction by a professor of language and literature. If ever there were a case for damnatio memoriae, it is surely that worthless loser, and I think it was a monumental lapse of taste to include this one name in a book designed to commemorate his victims. If ever this pamphlet is reprinted, which wouldn’t surprise me, for it is a very moving and impressive work, I hope the introduction will be omitted to remove this unhappy blemish. It wasn’t necessary anyway; the foreword gives all the context needed.

This apart, the work is truly powerful and memorable. It is always a joy to see technique used to some purpose, and here the notion of using words to create, literally, human faces on the page comes off brilliantly. Ruset states in the afterword that he had coincidentally suffered a personal loss of his own at the time, and this perhaps accounts in part for how sharply he evokes grief – “a hole in the silence” – and the getting used to it – “it was so un/expected to feel a moment’s/ peace”.

October 17, 2021

Review of "Beyond the Swelkie", celebrating the centenary of George Mackay Brown

(eds Mackintosh/Philippou, pub. Tippermuir)

The “swelkie”, for the avoidance of doubt, is the fearsome swirling current in the Pentland Firth that makes the crossing to Orkney more of an undertaking than its length would suggest. It has nothing to do with selkies, those mythical shape-changing creatures irritatingly over-used in poems (GMB did use one in An Orkney Tapestry, but typically he gave it an original twist; his is a seal-man, not a seal-woman).

This memorial is divided more or less equally between poems and essays. Some of the poems are about GMB, others inspired in some way by his own poems – you might be surprised by how many poems carry the epigraph “after George Mackay Brown’s ‘Beachcomber’” and imitate the structure of that poem. I think this can sound a bit like an exercise, and on the whole I preferred those which took a line or image of his and then spun off in a new direction, like David Bleiman’s “A Wee Goldie”, which has for an epigraph the line “He woke in a ditch, his mouth full of ashes” from “Hamnavoe Market”, but which deals with the guilt of those who out of mistaken goodfellowship enable alcoholics and end up at their funerals: “so here we stand in rain, who stood our rounds”.

Some poems are set in the kind of landscapes that inspired GMB, like Mandy Haggith’s “Knap of Howar” and Lynn Valentine’s curiously moving “Pilgrimage”, about the street in Stromness where he lived so many years. Only one didn't seem to me to have much to do with him at all. Disclaimer: I have a poem in this myself but am reviewing the rest of the book.

The essays are a blend of personal reminiscences (I never knew before that GMB was barred from the Stromness Hotel!) and critical appraisals. Alexander Moffat’s account of painting GMB’s portrait was absorbing, and Ros Taylor gives an affecting and sometimes surprising picture of him as an uncle – his habit of telling tall tales may be no more than was to be expected, but his helping his teenage niece collect Beatles press cuttings was more unpredictable.

I also wasn’t aware, until reading Pamela Beasant’s essay, that he prevented his early work An Orkney Tapestry from being reprinted – various reasons are suggested, but I suspect it may have been because he mined it so thoroughly for later work, especially Magnus. The most interesting of the critical pieces is Cait O’Neill McCullagh’s “An Orkney Worlding: George Mackay Brown’s Poetics as Waymarkers for Navigating the Anthropocene”. As the title would suggest, it is very jargon-heavy, full of words like poeisis and solastalgia, and I am finding it correspondingly hard going, fathoming a few sentences at a time before my head starts to ache, but what I have managed so far is very thought-provoking.

This essay, like several others, makes the point that GMB’s antipathy to “progress”, ie uninterrupted economic growth, looks a lot less quaint and old-fashioned now than it did some decades back. No doubt his reluctance to travel and his habit of keeping household goods till they wore out, and sometimes longer, were partly down to a disinclination to be bothered. But his rootedness and lack of interest in consumerism make him a landmark writer for a more eco-conscious generation.

October 1, 2021

Review of The Red Gloves and other stories, by Catherine Fisher, pub. Firefly Press 2021

“…he stood up there like someone important, spouting as if he knew it all, but he didn’t, did he? He had no idea. Were all adults such frauds, was it all false, the way they pretended to know things, to be experienced, to have learned, have passed exams? Were they really all fakes like he, Jack, was?”

It may seem perverse to start by quoting the one story in this volume that has no supernatural element. But in a way, “Not Such a Bad Thing” is key, because Jack, who has plagiarised a story from an old book for his English homework, is experiencing a revelation about how little the adults whom he has seen as omniscient actually know. His teacher has not spotted it, the head of English has entered it for a competition, the judges too have awarded it first prize. Jack acquires a new perspective on himself and his world, and this is what happens in most of the stories here.

Several stories are deliberately ambiguous as to whether the supernatural elements are “real” or a manifestation of what is going on inside the young protagonist’s head, particularly when the stories concern relationships – and often these protagonists are coping with being part of split and remade families. On one level, the antagonistic “Red Gloves”, maliciously unhappy with their new situation, clearly mirror the two young girls whose holiday friendship does not survive visiting each other at home. The sprite “Nettle” could well be a manifestation of Nia’s strong desire not to move house. But things are not as reductive as that. Chloe may long to be other than she is, but there is always the possibility that the “changing room” at her gym is just that, a room where people are changed into something else. The bird trapped in “The Mirror”, which Daniel entices into himself, could be emblematic of many things but it is also, terrifyingly, itself. And it would be very hard indeed to explain away either “The Hare” or “Ghost in the Rain” in purely realistic terms. If all-knowing adults can’t spot Jack’s plagiarism, what is “there are no such things as ghosts” worth?

A notable, and to me welcome, feature is the general lack of cosy “east, west, home’s best” endings. These children are not intimidated by encounters with the unknown: Chloe can’t wait to get back into the Changing Room, while Tom is clearly drawn to the “Silver Road” of dream, even knowing he may not be able to return from it.

The interesting introduction mentions how some of the ideas behind these stories developed into novels, but even without it, for a dedicated reader of hers, the parallels stand out – the menacing power of mirrors in several stories, prefiguring the Chronoptika series, the situation of grieving adults in a big house which foreshadows The Clockwork Crow, Chloe’s difficulty in deciding which is the “right” side, a dilemma faced by many a young protagonist in Fisher’s novels.

Although, as usual, any adult could read these with pleasure, it is important to bear the target audience in mind: the way Nia outwits Nettle is a very old folk-tale trope indeed and most adults would see it coming, but a child reader might well be meeting it for the first time. I doubt, however, that many readers of any age would manage to predict the killer ending of “Ghost in the Rain”. I didn’t. Nor, unlike some “surprise” endings, did it invalidate the story; on the contrary it gave it immediate new depth and sent me back to the start to read it afresh.

The book is a lovely artefact with a suitably menacing black and red dust-jacket, red bookmark and red-sprayed page edges. For those of you with young friends or relatives who like fantasy, ghost stories and good writing, it’ll make a fine Christmas present. I should buy it well in advance though, so that you can have a good read of it yourself first.

September 16, 2021

Review of “100 Poets: A Little Anthology” ed. John Carey, pub. Yale University Press 2021

With an anthology, one is reviewing both the individual poems and the linking concept. If I were John Carey, I fancy I would be annoyed by the description of this concept on the back cover: “an anthology of verse based on a simple principle: select the one-hundred greatest poets from across the centuries, and then choose their finest poems." This of course is preposterous: no one person could do it. You would need a committee of 25, speaking at least that many languages, and they would still be arguing by the end of the decade.

Sure enough, when one reads Professor Carey’s foreword, it becomes clear the sensible chap was attempting no such thing – in fact he was doing something far more personal. He sees the anthology as a follow-up to his A Little History of Poetry (which I haven’t read) and states “I have chosen 100 poets, mostly but not exclusively English and American, who seem to me outstanding”. As for the poem choice, “all the poems I have chosen are chosen for a single reason – that I find them unforgettable.”

What we have, then, is an avowedly personal, Anglocentric anthology of poets and poems that have made a great impression on a distinguished English academic born in 1934. This shows in the translated poems he chooses – “starting, where world poetry starts, with Homer and Sappho”. I am fairly sure several Eastern cultures, including India and China, could dispute this assertion, but in fact the translated poets are mostly those an Englishman with a classical education would have come across, ie Greek and Roman. Heine, Baudelaire and Rilke are the only ones from modern languages to get a look-in and the only sign of the Chinese poets familiar to many of us in translation is Pound’s pastiche of Li Po. Nor will you find translations of the ancient Welsh poets like Aneirin and Taliesin or, later, ap Gwilym.

He also includes biographical notes, of widely varying length, on the poets, and remarks that “other anthologies” do not give the reader any context about the poets and their times. I can’t help wondering how his experience has differed so much from mine, for I have several anthologies which do just that, starting way back with the Collins Albatross anthology, edited by Louis Untermeyer in the 1960s, which sorted poets into historical periods and provided an overview of each period. Most of my anthologies do also include biographical notes on individual poets, though not so extensive as the longest ones here.

In fact the biographical approach occasionally worries me a bit, when it seems as if poems are being chosen to illustrate the biography rather than for their intrinsic worth. The biography of Housman stresses his sexuality and so does the choice of poems; personally I would say his best poems were on the subject of his mortality, which was far more an obsession with him.

Among the pre-World War II poets, Carey’s personal preferences, though they skew what most would regard as the relative importance of some poets, often result in fascinating choices and mini-essays. Giving Ben Jonson five pages to Chaucer’s one may look perverse, but the five pages of interleaved poems and biography make good reading. I also like his choice of two W H Davies poems far stronger than the over-rated “Leisure”. And the absence of poets still living is right and proper; there has not yet been time to establish their reputation beyond doubt.

Post-war, however, some of his omissions seem frankly odd. In particular the absence of the whole 20th-century Scottish group – no Edwin Muir, Norman MacCaig, Hugh MacDiarmid, Edwin Morgan, Sorley MacLean, George Mackay Brown – is remarkable. I can reluctantly accept that not everyone may share my view that Sorley MacLean’s “Hallaig” is the greatest poem written in these islands in the 20th century, but this total omission of a whole national group leaves one wondering if some Scottish poet once did him a terrible injury (Henryson and Dunbar are missing too; in fact it seems Burns was the only Scot ever to pick up a pen).

Nor do Welsh and Irish poets fare much better, or Commonwealth ones. Two Dereks, Mahon and Walcott, may possibly still have been alive, and therefore ineligible, while he was compiling the anthology, but it could as easily be that they weren’t part of his personal, very Anglo-American canon.

There are also inclusions which will surprise – some for better reasons than others. May Cannan is a neglected poet, though I have seen her in Great War anthologies, and am glad to see her here. I’m not sure, though, that I ever expected to see Arthur Hugh Clough’s “Say Not The Struggle Naught Availeth”, McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields” or Pudney’s “Johnny Head-in-Air” in an anthology edited in 2021, and I can’t credit that they are there for any poetic merit. Rather, all three had a powerful emotional effect on certain generations of English 20th-century readers.

I found the anthology oddly fascinating for what it reveals about the mindset and preferences of educated English (not British) readers of a certain time – it is really an anthology of what influenced them and featured in their early reading. It also takes off when he comes to what seem to be his personal favourites – Jonson, Marvell, Milton especially.

But to my mind it is being marketed as something it was not intended to be. Carey claims nothing but personal liking for his choices, but the publishers seem to regard these choices as a sort of guide to what is universally accepted as “the best”. In fact it is a personal canon, and all such canons are heavily skewed toward what the compiler read in youth. If one is an avid reader, one will add to this canon when older, but sometimes not as much as you might think, and for sure, some choices will look terribly out of date to the next generation, who have not the same emotional attachment to them.

Is this, as the back cover claims, an “accessible introduction to the best that poetry has to offer”? Well, some of the best (and some a long way below it), for its Anglo-American centricity, in both language and culture, cannot be denied.