Sheenagh Pugh's Blog, page 15

August 15, 2020

Review of The Tin Lodes by Andy Brown and Marc Woodward, pub. Indigo Dreams Publishing 2020

A stream

a sprinkling

from separate sources

Here’s a collection of poems co-authored by two poets living on opposite sides of the River Teign. It begins in the region of the river, then radiates out to other waters both national and international. It is as interested in the banks as the water, and in the lives lived out on them:

The ferry plies its trade across the harbour;

small queues grow and vanish on opposing shores.

A frequent technique in the early poems is to blur time periods, as if the river holds them all in its memory at once:

a conclave of waders watch a Bronze Age

fisherman navigate his coracle

over to a niche in the rocks. He chants

his hunting prayer and parts a veil

of seaweed to reveal cormorant squabs

awaiting a parent and fish for their gullets.

Downstream the overflow pipe lets slip

its secret, jarring song into the sea.

This collapsing of time happens too in the central “Tin Lodes” sequence, where the old stannary chimneys become

weathered coastal sentries in spring sunshine

that could have been the ruins of Mycenae

and in coinages like “Mr Pytheas, the Marseilles merchant” for Pytheas of Massilia, the first to trade in Cornish tin for the Roman empire.

The vocabulary of these poems is often specialised: obviously place-names and species-names are important and sometimes become incantatory; the languages of trades, like tin-mining, and of botany and geology also figure heavily. Mostly this just makes things more interesting, though there are times when it sounds a bit too much like a scientific article – at the second mention of “kaolinitic”, it did strike me that this was probably a word you could only get away with once in a book of poems. There are also a great many dialect words – there’s a glossary at the back, which is just as well. This isn’t quite the same as writing in dialect, which would also involve grammar and sentence structure; it’s more the replacement of individual standard English words with dialect equivalents. Again, this is mostly fine but occasionally looks overdone, as if the words were being searched for. Actually, in one short poem, “The Dark Acre”, they clearly have been: the poem reads like an exercise in replacing all the standard nouns and most of the adjectives. This poem is in a short sequence called “Tributaries” and I would guess the idea is to illustrate how local cultures merge and broaden, like the tributaries of a river, eventually flowing into a supra-national ocean.

Another aim would seem to be to show what rivers, oceans, waters in general, have meant to people over the centuries: trade, communication, barriers, danger, escape. The final poem, “My River”, spends most of its time telling us what it is not; not “Alice Oswald’s Dart, or Wordsworth’s Thames,/or Raymond Carver’s river that he loved”. The implication being that everyone has his or her own river, their own path to the ocean, a suggestion reinforced by the poem that impressed itself on me most strongly, “Beach Huts”. In this, an old lady has gone missing, or at least not been seen for some time. “Police believed she’d gone to Birmingham”, that most land-locked of cities, but in spring, when facilities are cleaned out and renovated, it turns out that she has found a better place to die, in a beach hut, presumably looking out to sea, her fist “locked around the key”.

As Melville observed, water has a powerful pull on us: "Narcissus, who because he could not grasp the tormenting mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned. But that same image, we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life”. For me, the poems work best when they foreground this atavistic fascination. There are moments when I could wish to be less conscious of the research; facts and information, intriguing as they often are, sometimes drown out the sound of the river for me. But moments, too, when it comes through very clearly:Now, into this brackish reach

the tide is running. Sliding through underwater grass,

current tracers in the blind depth,

I can sense them – the eels are coming…

August 1, 2020

Review of Allegation by R G Adams, pub. Riverrun (Quercus Editions) 2020

Kit, a young social worker, and Vernon, her mentor, are in a meeting with legal adviser Sue about a difficult case. Vernon, in his sixties, is getting a bit jaded with officialese:

"Vernon briefed Sue Sullivan while they waited for the Coopers to arrive. Kit handed her a copy of the proposed supervised contact agreement and she scanned it.

‘They’re going to want mother supervising contact. That’s going to be a major sticking point. Why don’t you trust her to do it?’

‘She’s arsey,’ Vernon replied.

‘Right. Or as we will perhaps put it, we don’t feel we can rely on her cooperation as yet.’

‘That’s it.’"

It is this kind of dialogue which tells you at once that you are listening to an author who knows whereof they speak. Its easy assurance reminded me of Mike Thomas’s police procedural novels, and this novel is indeed also set in South Wales, but here for “police” read “social workers with special responsibility for childcare”. Kit and Vernon spend their days trying to protect children, knowing that if they read one of their overload of cases wrong, they will be crucified by the press for either breaking up a family or failing a child.

Kit has been assigned a case that is really beyond her experience, because her department is understaffed and what staff there are, tend to burn out and go sick. A man has been accused of abusing two young girls over a decade ago. Since then, he has married and had three children, one of whom is the same age his accusers then were, hence the interest of social services. To make matters still more tricky, he and his family are educated, articulate middle-class with influential connections, not the sort to be overawed by authority.

I don’t think it’s any spoiler to say that from the outset it does look as if there is something not quite right about this family – the question is what, from whom it emanates and most of all, whether Kit can find any proof for it. Indeed, the alert reader may pick up some hints more quickly than Kit does, mainly because we do not have 15 similar cases to think about at the same time. Even then, though, we shall find our opinions of people constantly shifting, as hers do, and having to remember Vernon’s warning that nobody is all of a piece.

These salutary thoughts will not stop the reader occasionally yelling at Kit, “listen to X”, or “find out about Y”, because that is where much of the tension resides. Kit is herself a survivor of a neglectful mother and a care home, and one of her siblings, Tyler, is still haunted by childhood events which Kit is trying to help him cope with. One thing that comes over very clearly from this novel is how easily an inexperienced, overworked person with worries of their own might miss, or misinterpret, something vital to a child’s welfare. It is significant, I think, that some of the most important things Kit finds out, both about this case and events in her brother’s past, she discovers by illicit, or at least not-approved-of, means - if she went wholly by the book, the ending would be very different.

This is a whodunnit, a did he dunnit, and if he dunnit, can they prove it? Which makes for a constant page-turner. It is also a Bildungsroman for Kit, a likeable and credible character, but above all it is a testimony from a very hard place to work, by someone who quite clearly has been there, done that. Please don’t shy away because of the difficult nature of the material – the book, cannily, does not, in fact, dwell on harrowing aspects; it is enough to hint at them. There is humour, too, in Vernon’s battle with tidier souls who talk in management-speak and care more to protect their own backsides than anything else. But above all, there is this assurance, the feeling that we are listening to an author completely in control of their material, as we see from the first time Kit enters her open-plan office:

"The noise level was rising as dozens of phones rang and social workers rushed out on urgent visits, or in to make phone calls and get advice from their seniors. Impromptu meetings were going on all over the place: at desks, in corridors, in the coffee area and outside the toilets. Snippets of conversations reached Kit above the hubbub as she passed each team. One social worker was anxious about a teenager, a regular selfharmer who had gone missing from care over the weekend and had not yet turned up. In another team, the manager was trying to allocate the usual batch of domestic-violence referrals resulting from the weekend’s rugby-related drinking, her staff trying not to meet her eye. Wales had lost, Kit remembered, so no wonder they were reluctant to volunteer.

As Kit passed the Youth Justice Team, she spotted a young social worker sitting in silence with the phone to her ear, tears rolling down her face. Even from a few feet away, Kit could hear the furious shouting at the other end."

July 21, 2020

Review of Going Back by David Wishart, independently published 2018

Corvinus, unwillingly attending an imperial dinner, consoles himself with the reflection that at least the current emperor is a bit saner than the last one…

"Claudius was a different kettle of fish altogether; at least you could be certain that when you turned up in your glad-rags with your party slippers under your arm, he wouldn’t be got up like a brothel tart or Jupiter God Almighty complete with gold-wire beard and matching toy thunderbolt; our Gaius had had style, sure, no argument, but you can take that sort of thing too far. With Claudius, the worst you could expect was a lecture on Etruscan marriage customs and a detailed explanation of why the alphabet could really, really do with a few extra letters."

The trouble is, of course, that Claudius wants another favour. His mother-in-law is pestering him to find out who murdered the husband of an old friend of hers – in Carthage. Cue another journey to the outlying parts of the empire for Corvinus and family, with Perilla delighted at the prospect of new monuments to explore and Bathyllus resigned to another sea crossing.

Corvinus has the usual problems – plenty of suspects, since the victim, wealthy landowner and businessman Cestius, was not popular even within his own family, and, the bane of all investigations, the fact that most people have something to hide, and will lie accordingly; it’s just that the something in question may not be murder. In addition, an apparently accidental death and an apparently completely unrelated street murder worry Corvinus, who has a hunch they are somehow relevant. Nobody shares his view, not even Perilla, and she and Corvinus are also at odds over two of his suspects, a couple to whom she’s taken a great liking.

So basically the mixture as before, albeit in a fresh setting, with Corvinus getting up people’s noses, trying to avoid being beaten up and trying even harder to avoid the local speciality, date wine, which he’s been reliably informed is even worse than German beer. He also has to attend a formal dinner party hosted by the local governor, none other than our old acquaintance Sulpicius Galba, which proves a more fraught occasion than the one with Claudius… Corvinus is convinced that even the guest list has been compiled with a view to ensuring he never comes again:

"There was Lutatius the banker with the cleft palate and his wife Quadratilla, sixty if she was a day, dressed and made up like a thirty year old, who had a laugh like a marble-saw: Rupilius, owner of the biggest undertaker’s business in the city, who looked the part and whose hobby was undertaking, plus his acid-tongued harpy of a wife Lautilla, whose hobby seemed to be slagging friends, acquaintances and total strangers off at every opportunity, and finally a guy I can’t remember the name of who sat through the whole meal without saying a word to anybody."

The plight of slaves in the empire gives him pause for thought again, as does the difference between law and justice, and we learn (painlessly via Perilla) some fascinating facts about the region’s history and its relationship with Rome. My one criticism would be that it seems a shame to take Meton all that way and then give him so little to do in the book – Bathyllus, though, proves to have a vital contribution to make to solving the mystery, as does an ill-behaved pet monkey.

I'm adding a couple of reviews of older Wishart books because I discovered some folk were no longer becoming aware of new ones now that he is self-publishing. To find more, and keep up to date with him, go to his website at https://www.david-wishart.co.uk/

July 11, 2020

Review of Loose Canon by Michael McNamara pub Subterranean Blue Poetry

My accent now echoes those around me.

We blend in. Displaced adapters.

This lively collection opens, appropriately, with a poem called “No Fixed Abode”. The abode in question is Newport in Wales, a town which has been absorbing newcomers for a very long time:

From Coomassie Street to the Jamia Mosque

the Somalians, Syrians and Eastern Europeans

have inherited the patois of a multi-cultural community.

“Awyite? Laters b’ra.” Now - see those strange shaped mountains?

They are Celtic hill forts. Beaker people burial barrows.

Pagan migrants and blood letters. Artists and innovators.

Us.

The speaker, himself displaced, is moved to reflect on his Irish roots and on the concept of “home”. The long, loose lines of this poem move easily and anything but prosily; it’s a style that suits him. Sometimes when he uses shorter lines, I can feel him pausing to think at the end of them, and the momentum falters. This tends to happen when he’s trying to make a point rather than listening to the sounds and rhythms he creates. Usually he listens a lot to them and they often impel the thought–line of the poem – for instance, in “Wise Whispers Extant”, “whimpers” leads on to “whispers” which in turn suggests “prospers”. Or words and images suggest their opposites – “walk through closed doors/with open veins.” In this he reminds me a little of Kate O’Shea, whose thought process in her collection Homesick at Home is similarly often shaped by word association of various kinds.

At around 140 pages, I do think this collection is too long; there are poems in it, particularly towards the end, that need more polishing and haven’t really progressed from vague thought to finished poem yet. Basically he has two modes; observational and contemplative, and I much prefer the former. I don’t think this is purely personal preference: when he is in observational mode his poems have far more momentum than when he is considering life, the universe and everything. His language is sharper too; it is in observational poems like “Returns” that we get lines like this, with its inspired opening adjective: “Unaffiliated sheep are painted red and blue by home team supporters”. These observational poems are also free of the verbal tic, prevalent when he’s philosophising, of asking an inordinate number of questions, to which the answer may or may not be 42.

He needs more control: there’s thought that provokes and musings that go nowhere, wordplay with a purpose (like “From nights out, on the mean, bleak street/to nights, out on the three-piece suite”) and mere playing with words. And he could do with a bit more rigour sometimes, to eliminate the odd slack, cliched or sentimental phrase. However there’s no doubt that when he’s on form and in control of his deeply felt pleasure in words, he can be both skilled and memorable. “Returns” may ramble a bit, but besides the unaffiliated sheep we get this striking evocation of place:

Achill Island. One unforgettably sun steeped day.

Still. Like a breath held. So still. Bordering a bleached, deserted village,

a white sand sanctuary, a beach spilling in to clear, ice blue water.

The mute Slievemore mountain, a grave with my name at its foot.

And in “Somewhere” we have these eccentric yet oddly effective line breaks creating a huge, eloquent hesitancy:

Something called loneliness. Which

was once just a word. Becomes a

feeling. Somewhere on this journey.

This is 140 pages to dip in and out of; I would never claim it worked all the time. But when it does, it can be memorable and promises better for the future.

July 1, 2020

Review of Trace by Mary Robinson, pub. Oversteps Books 2020

Mary Robinson is here on her second collection, in which she shows that she has some interesting ideas of her own, particularly about imagery. It isn’t just that she can coin a striking image – though I especially liked her comparison of an iron ring, not the finger sort but more like a mooring ring, to “a hagoday to knock/on the earth’s sanctuary. (A hagoday, for those who like me would have to go online to find out, is a door-knocker on a place of sanctuary.) It is more that she has interesting things to say about the purpose of imagery. For instance, in “Beech Trees”, she opens with

They remind me

of those women

who had been to Girton

or the Slade

From here on, you can forget the birch trees: the poem is wholly about a certain type of woman she recalls from her youth, and whom she evokes with a wealth of tender detail, from the “long grey hair” and “brown tweed skirts” to the cottages they turn into refuges for artists and poets. The birch trees do put in a brief appearance at the end:

It’s the way the trees are curious

shapes and look down from the hill

and do not think about themselves.

But essentially, the comparison object has completely taken over from the nominal subject of the poem – which is now not so much about beech trees as about what memories they stir in one particular person.

In another poem she attempts to find a word for “the sound of a dog’s paws/on frozen leaves”. She details exactly the immediate circumstances: the dog’s weight, how his movement disturbs the leaves, and the background of the chilly morning:

Far off to the south-east

dawn burns. A heron studies the river.

But then, coming back to the sound, she tries and rejects various verbs like crunch, crack and snap before concluding

It’s the sound of movement on a still morning,

the sound of a dog’s paws on frozen leaves.

This premise, that sometimes exactitude is achieved not via one perfect word or image but via the building up of details and situation, strikes me as interesting and the polar opposite of those ill-advised creative writing manuals and lesson plans which would have us believe there is always a dead-right verb or noun that will eliminate any need for those despised chaps, the adjective and adverb. From the acknowledgements, it is clear she spends a lot of time in writing groups, but she is obviously capable of striking out beyond groupthink and doing things her way.

However… It seems odd to say that one thinks a poet is too self-effacing, still odder to say she is too collaborative or too eager to credit influences, but I do have some such thought. It comes through in some of her title choices. The poem above, about the dog’s paws, is one of the best here, but its title, “You asked for a poem about listening”, does it less than justice, making it sound like an exercise. Another is titled “Poem with a phrase from Amy Clampitt”. The phrase in question, to judge by the italics, is “Nothing stays put”, and I really doubt Ms Clampitt would claim to be the inventor of that phrase or the only one who ever used it. Don’t get me wrong; I am all for poets acknowledging any borrowing, but this one could have been credited in a footnote, or still better, notes at the end of the book where they don’t impinge on the reader unless wanted. It didn’t need to be elevated to a title, as though the whole point of the poem had been to re-use this phrase.

Influences work best when they have been absorbed so far into the poet that they act almost unconsciously. Here, one senses that she feels a need for something to lean on, as if she hasn’t enough confidence yet in her own ideas. There is a sequence of poems about, and often in the voices of, various Shakespeare characters, “A Comonty”. These poems work best when they add something new - Dorothy Wordsworth reflecting on Timon of Athens, or the poet herself re-reading the Merchant and recalling how it was taught at her school with no reference to

why there were Polish girls in class

with long hair and longer names that plaited

round the teacher’s tongue.

They work less well, for me, when they simply give a voice to a character who already had one. There are times, too, when she tells us a bit too much about the writing process, as in “Clustog fair”, where we learn that “I look up the Welsh for thrift”, and later “I read it is from the plumbago family”. This is to leave the scaffolding up, or the pencil lines on the painting. Again this feels like a lack of the confidence to go boldly in and just tell us what she now knows, rather than how she came by the knowledge.

To judge by the best poems here – I could mention also “daffodils da capo”, in which, as in others, she shows a refreshing willingness to experiment with lineation rather than being bound by left-hand justification all the time – she could well afford to be more self-assured about her own voice.

.

June 16, 2020

Last book in the Clockwork Crow series out in October!

Who wants to read the first chapter of The Midnight Swan, Catherine Fisher's finale to the Clockwork Crow series? it's here!

June 15, 2020

Review of Dead Men’s Sandals by David Wishart, independently published. 2020

“The litter lads pulled up outside Eutacticus’s gates. We de-chaired under the watchful eye of the gate-troll and carried on up the drive past topiaried hedges studded with serious bronzes and enough marble gods, goddesses and nymphs to equip a pantheon. Greek originals or specially commissioned, probably, the lot of them: in Sempronius Eutacticus’s case, crime didn’t only pay, it came with a six-figure annual bonus and an expense account you could’ve run a small province on.”

Some folk will know already that my favourite fictional detective is Marcus Valerius Corvinus, first-century AD aristocratic Roman layabout who has a distaste for the life of public service and self-aggrandizement expected of his class, and a penchant for furkling about in the dirty laundry of people who’d prefer it to stay hidden. He also talks a bit like a Raymond Chandler narrator.

Some of the Corvinus books are political; this is not. Corvinus owes a favour to a character we have met several times before, the crime cartel boss Eutacticus, who is not one to forget what he is owed. He sends Corvinus to Brundisium, to investigate the murder of the local crime boss there, who was a friend, in so far as Eutacticus had any. The dead man’s granddaughter had been engaged to the son of a long-time rival, in an apparent business deal to unite the two crime families, and it looks as if this might have led to his murder. But an extremely valuable antique ring he had given the prospective bride is also missing, and though Eutacticus wants to know its current whereabouts, he is oddly reticent about it. So is everyone else….

As usual there are plenty of suspects and Corvinus’s wife Perilla plays a major role in helping him think things through and discard various theories. Obviously, this being a whodunnit, I’m not about to give plot details away, but in fact there is an unusual twist to the solution, which requires the reader to rethink the words “guilt”, “justice” and “perpetrator”. Another interesting development is a woman heavily into Eastern religion. This is reminiscent of a character in the earlier book Family Commitments, Pomponia Graecina, who was festooned with amulets and talked to trees. Graecina is an historical person who would, somewhat later in life, be reputed to be among the earliest Roman Christians, and though the character in this book is a member of the cult of Isis, her inclusion does indicate a growing movement away from Olympianism – not that Corvinus would be anywhere near as interested in that as he would in what the local wineshop is serving.

This series works for me as much because of the characters as the plots: Corvinus and his somewhat anarchic household are eminently believable and feel like friends by now. Also the books don’t mind tackling questions you don’t always expect to see in genre novels, as indicated above. Another and arguably even more daring example of this in the series is Solid Citizens, reviewed here.

One minor quibble: Wishart as usual does give us a list of characters, but given that his hero's name is Marcus, he could have made life a whole lot easier by not giving one of his crime dynasties the family name of Marcius and another character the personal name of Marcus.

A minor quibble indeed, given the gratitude I felt when the latest Corvinus came through the lockdowned door.

June 1, 2020

Review of Almarks: Radical Poetry From Shetland

Review of Almarks: Radical Poetry from Shetland, ed. Jim Mainland & Mark Ryan Smith, pub. Culture Matters 2020

Off Skyros at midnight

The heads of the little drowned children

Gently knock against the hulls of the yachts. (Stuart Hannay)

This is an anthology of radical poems from living poets in Shetland, which at once raises the question of “what’s radical?”. Jim Mainland’s introductory essay indicates that he takes it to refer both to subject matter and style. This essay is a joy in itself; I shall treasure his demolition of the buzzword “virtue-signalling” - “surely the most linguistically flat-footed of insults – imagine Shakespeare coming up with something as weak as ‘take that, you virtue-signaller!’”.

It’s arguable that writing in dialect rather than “standard” English is itself radical, and not including a glossary of dialect forms even more so. There are several poems in Shetlandic, and I found them accessible enough, but then I’ve been around the dialect for a while now. If you can follow Ola Swanson’s high-energy polemic on the locally controversial topic of windfarms, “Da Carbon Payback Kid’s Ill-wind Phantasmagoria”, you’ll be fine:

We tak in Windhoose, Flugga, an spend da night under dis baby,

da crazed Shelthead telt me, an du widna want ta dae it too often.

On migrations it’s a big bird windfeast

o waarblers an laverick tongues in aspic

an see whin a raingoose hits it’s lik instant pâté, min.

A wind-sooked inta-gridpooer guy gae me da wikiphysics

but I already hed a lingerin o it fae da Bridders Grimm.

Da whole rig set up a vibe an drave you gibberin ta money.

One thing that comes over as “radical” from this lively piece is how dialect can be employed on the most contemporary of themes, rather than being the preserve of folk song and nature poems. Laureen Johnson, in “March-past at Arromanches”, written after the 50th anniversary of D-Day (how time does fly), uses the dialect’s homeliness to cut through the pomp and ceremony:

But oh, in every waddered face

you see da eyes o boys.

And Beth Fullerton, harking back to a time when standard English was enforced in schools, feels an instant rapport with the poem “I Lost My Talk” by First Nations poet Rita Joe in Ottawa’s Museum of Nations. It’s possible that those whose native dialect is standard English will not appreciate fully the radicalism of “Tongue”, but Welsh, Scottish and Irish readers should have no bother:

You tried to tak my midder tongue

bit sho wis always dere

waitin

beyond da riv

o your horizon

Among the non-dialect poems, Raman Mundair’s “Let’s talk about a job” is memorable both for its subject matter (a job advert for an under-qualified, compliant doctor to work at an immigration detention facility in Louisiana) and its form, which is an unclassifiable but powerful melange of poetry, prose and drama. It’s also hard to quote from, because it uses a lot of repetition to build up a huge head of quiet but boiling anger. Its understated, matter-of-fact language is the antithesis of the ranting sometimes associated with “radical” poetry and far more effective. I would love to see it performed.

There’s only one poem by co-editor Jim Mainland, which is modest of him but a pity, I think, because he is in many ways one of the most radical writers in Shetland and any anthology of contemporary radical Shetland poems that doesn’t include his poem “Prestidigitator” has a serious lack. There are also several images (I think mainly abstract paintings though some might be photos) by Michael Peterson, including the cover image reproduced here.

Declaration of interest: there are also three of mine here, but as usual I decided it was reasonable to review the rest of the anthology.

This being an anthology, the quality, as always, is variable. There are some pieces I like less than those above, and all readers will find that so – nor will the poems they like necessarily be the ones I like. But they should all find a lively, thought-provoking body of work from a great variety of artists. One radical aspect of this anthology is its inclusiveness: we have as many female writers as male, including a trans female writer, and though BAME voices are thin on the ground in Shetland, the most striking piece in the anthology is from an Indian-born Shetlander. An almark, by the way, is a sheep that habitually breaks bounds. It’s a good word.

May 20, 2020

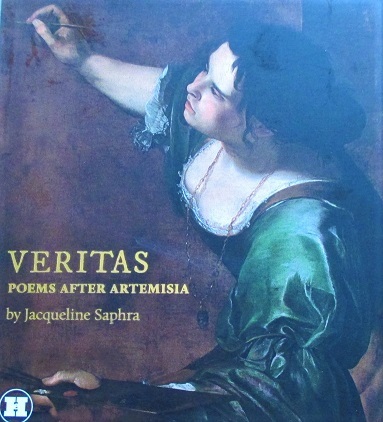

Review of Veritas: Poems after Artemisia by Jacqueline Saphra, pub. Hercules Editions 2020

A woman paints herself

There could scarcely be a more suitable project for Hercules Editions, with their emphasis on poetic/artistic collaboration, than this sonnet redoublé (or heroic crown) riffing on fifteen paintings by Artemisia Gentileschi, each sonnet opposite its generating painting.

Gentileschi’s habit of using herself as a model lends itself to autobiographical interpretation, and one thing that comes over very clearly from her paintings is strength: not only her Judiths and Jaels but her Danaes and Lucretias are powerfully built, with determination in every line of their faces, nobody’s pushovers. Lucretia, as the poem on “her” painting remarks, is not aiming her blade, in the approved manner, at her own heart; rather she is pointing it away from herself, as if wondering at whom it might more usefully be aimed, and this cannot but remind us that Artemisia, in the same situation, had no use for suicide; she rebuilt her life on her own terms.

I tilt

the handle, angle it upwards, as if to taste

the salt of vengeance. Hmmm. Who could I kill?

It’s interesting that her parents named her, not after some saint or virtue (like her mother Prudencia) but for a pre-christian queen who personally commanded a battle fleet. Her father Orazio doesn’t always get the best press, but he does at least seem to have recognised and fostered her talent. She, however, is the one who works out how to “build the brand/and market it”. Despite the need to please patrons and public taste, she comes over, both in the paintings and these poems, as totally in control, taking control both of her signature subject matter and her interpretation of it – “she’ll pick her story, choose the way to spin it”.

This being so, one can see the reason for the choice of form. A crown of sonnets is fiendishly complex; an heroic crown even more so: the poet must begin at the end, with the master sonnet, and then construct the other 14 to a pattern whereby the first sonnet begins with the first line of the master sonnet and ends with the second, beginning a chain; the second sonnet begins with the second line of the master and ends with the third and so on until the 14th sonnet begins with the 14th line of the master and ends with the first, completing the chain. Ideally each of the first 14 sonnets examines some aspect of the theme while the master, at the end, brings them together.

The trick, of course, is to ensure that all the key lines still make sense in fifteen different contexts, and even with slight variations it isn’t easy. In some ways it is more like architecture than writing and demands a high degree of control which seems eminently well fitted to this subject, a woman rewriting her own story, arranging and shaping the material of her life to suit herself. Ekphrastic poems don’t always work for me if all they do is describe what I can already see in the painting; there needs to be a degree of reinterpretation, so that one ends up seeing more in the painting. In “Susannah and the Elders” we hear Susannah’s voice (or is it Artemisia’s, thinking in her person?) defining exactly what is going on, in terms that seem to telescope three time periods, Susannah’s, Artemisia’s and our own:

The elder puts his finger to his lips. Hush!

Silence, fear and shame; the go-to tricks

to nail a woman: timeless, quick, no need

for force. But this one doesn’t go to plan.

There is a dry, dark humour about many of these poems, which again sounds fitting for this tough, practical woman: the “well-overdressed” Angel Gabriel of “The Annunciation”, the “giant infant’s rump” of “Virgin and Child with a Rosary”, the satyr who is left looking foolish as he clutches the fleeing Corisca’s false hairpiece, the golden rain of “Danae":

Between her thighs

the coins line up, like she’s a slot machine

gone wrong.

This sequence is a terrific technical achievement, making a nonsense of the notion, still oddly prevalent, that poems in strict form are stilted or mechanical – these couldn’t be livelier. But what makes them memorable is the way they use the paintings to find a way into a life which was of its time, yet transcended its “age of limits”.

May 11, 2020

Review of Edgar Allan Poe and the Empire of the Dead by Karen Lee Street, pub. Point Blank 2020

Let’s begin with the potential problems and explain why they don’t exist. This is the third in a trilogy, the first two of which I have not read. Did it matter? No, not in the least. The story is free-standing in itself; the characters from earlier books soon establish themselves and any necessary background is conveyed naturally and without sounding like a lecture on What Happened Before You Came In.

Secondly, the narrator is Edgar Allan Poe and the other principal character is his fictional detective Auguste Dupin. Had I read The Murders in the Rue Morgue? I had not, and in fact know very little of Poe’s life. Again, it didn’t matter. No doubt those who are better informed will find an extra dimension to the tale, but essentially what we have here is an historical whodunnit, though the question is not actually so much whodunnit as how they dunnit and whether they can be apprehended before they do anything worse. And anyone who enjoys hist fic and detective fic will be well capable of enjoying this.

Our narrator, whatever his historical provenance, comes alive very well: a man keenly aware of the world around him, grieving for the recent death of his young wife, gamely trying to stick to a pledge of abstinence from drink, sensitive to environments and atmospheres, with a dry wit. The narrative actually begins with his own impending death and then goes into flashback, a stylistic trick that shifts the reader’s interest from “what happens next” to “how do we get from A to Z?”, and which works particularly well in a narrative where many will already know what happens at Z. The beginning of the flashback – his narrative of how he got from A to Z – sees him in his garden, in surroundings that would be idyllic were they not empty of his dead wife:

The cherry and apple blossoms had flurried down weeks previously and there were nubs of fruit on the boughs as spring ambled into summer. The foliage was still a tender green and rain in the night had scented the air with the richness of loam. I examined the wildflower garden I had planted in the shade under my wife Virginia’s guidance

Poe is by no means the only historical (or fictional) character to put in an appearance; one of the most entertaining scenes in the novel involves a literary salon where we run into George Sand, Eugène Sue and a rather irritating mouthy young poet who idolises Poe and whose first name is Charles…. But this is a novel where locations are as important as people. The “empire of the dead” is the tunnels and catacombs beneath Paris, where much of the action takes place. This is a promising location, and the Poe who reacted so keenly to the beauty of his own garden is as acute on these more sinister surroundings:

Golden light shimmered along the bleak walls, but our four lanterns did little to dispel the malevolent atmosphere. Sounds were amplified: pattering feet, the flutter of wings, chatters and squeaks—sounds that might fill one with the joy of nature in a woodland or some attractive city park, but evoked nothing but dread in this tomb-like space.

The solution to this mystery depends partly on something that might loosely be called supernatural, though it’s perhaps more correctly described as a bit of steampunk science. For anyone who feels uncomfortable with non-natural explanations, there is the odd hint that Poe’s abstinence regime may not be quite as strict as he claims, and that alcohol has a powerful effect on him. But in a genre where historical and fictional characters walk down the same streets, not to mention very creepy subterranean passages, suspension of disbelief does tend to be easier than, say, in kitchen-sink drama. The most important thing about a whodunnit, in whatever sub-genre, is that it should be a page-turner, which this is. But it also helps to have engaging characters and a fluent writing style, as this does. Our narrator’s voice is not pastiche Poe but does sound a completely credible voice for someone of his time and place.