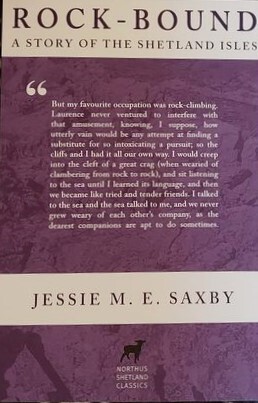

Review of Rock-Bound by Jessie M.E. Saxby, pub Northus Shetland Classics 2022

“While restraining and checking in some things, as if I were a mere child, she sought to make me feel and act like a woman of mature years in other ways. For instance, when I wished to accompany Mrs Weir, her daughters and other families to a luncheon-party on board the war-vessel at that time stationed in our vicinity, she declined the invitation for me on the plea of my extreme youth; yet when I came downstairs by a succession of jumps from one flight of step to another, she reproved me for not showing the maidenly dignity which pertained to my years.”

Daughter’s place is in the wrong, in fact, and much of this early novel is concerned with a fractious mother/daughter relationship. Which in itself is sufficient explanation for Saxby’s irritation when reviewers at the time (1877), took it for partial autobiography, for while our heroine Inga’s mother is cold, unloving and self-obsessed, Jessie Saxby’s mother emphatically was not, and the author would not have wished that inference to be made. Nor was Saxby’s childhood isolated like Inga’s, for the high-achieving Edmondstons, her birth family, not only had many children (she was the ninth of eleven) but regularly entertained visitors from all over the kingdom and beyond. It is clear that Saxby, like all writers, used and transmuted elements of her own life – the grove of trees by Inga’s home is recognisably the plantation that so individualises Halligarth, Saxby’s childhood home, on otherwise almost treeless Unst. But there is a great difference between using material from one’s own life and “being one’s own heroine” as some obtuse critic apparently suggested was the case.

Though Jessie had written poems and stories from childhood and published her first story at 18, this is a first novel, and has some of the faults that might be expected. It revolves around three things: a child’s relationship with her absent father and all too present mother, a “love-triangle” and a mystery. The first two are skilfully handled; the drawing of character and relationships was clearly a strength of hers. The third, if one looks carefully at the plot, has more holes than a Shetland lace shawl, though I am bound to say that one does not notice the improbabilities much while caught up in the story, for she keeps up the narrative momentum well. Whether it would survive a second reading, without the tension of “what happens next” to distract one from questions, is another matter. Certainly the ending, with its convenient dead-of-the-fifth-act solutions for characters no longer needed and its echt-Victorian insistence that All Will Be Well If Only We Trust In God, is downright irritating – though Inga’s earlier attempt to cure herself of sorrow by means of doing good works in the neighbourhood is not; one can well believe such distraction would be therapeutic.

But the compensations are many. The characters are skilfully drawn and often engaging. Constantly-fainting Laurence, Inga’s cousin, is a wuss, but a believable one; Inga’s aloof mother, “The Lady”, a fascinating puzzle. The informal, bordering-on-rackety Weir family, who actually sound a lot more like the Edmondstons than Inga’s family does, are a delight. Their son Aytoun, though he does tend to patronise Inga a bit, is an easy man to fall in love with and his sisters’ conversation gives Saxby the chance to indulge some of her feminist leanings, as in Kate’s reaction to her older sister’s soppy behaviour when engaged:

“Oh, my dear,” cried Kate, “it is nothing to what I shall be when my turn comes. I shall not speak a word of fun or look a person in the face for months – not, in fact, until the chains are bound on me by the cruel hands of my ‘inflexible papa’. I shall scream off into hysterics whenever I am spoken to and swoon gracefully whenever the beloved object approaches. I shall indulge in weeping extensively, and sigh whenever I see the moon.”

This picture of tricksy, laughter-loving Kate was too much for me, and my mirth ran over as abundantly as even she liked to see. The mischievous maiden heaved a comic sigh and proceeded – “I do trust the fever will go straight through the house in the order of our ages. There is the prospect that it may do so, having begun at the eldest, for in that case I shall have respite until Lily and Aytoun are comfortably married and done for.”

Saxby’s own marriage had been a love-match, and a happy one, but when it was ended by her husband’s early death, she managed to support her five sons by her writing. She did not remarry, and one gets the impression that while she had nothing against marriage, she could be as happy living independently. The initial E in her name stands for Edmondston, her birth-name, and it would seem that at heart she was always a member of that brilliant clan, for though she lived many years in Edinburgh she eventually moved back to Unst, the island of her childhood. Vaalafiel, Inga’s island in the novel, is not identical with Saxby’s Unst, but many of their geographical features are alike, and in an odd way, the very absence of much “place description” in the novel is testimony to how ingrained the landscape was in her, so much so that it seldom occurred to her to remark on it. (It is also true, I think, that human beings simply interested her more than landscape.) But her brief pen-portrait of the island, early in the novel, is a fine example of place description doing more than appears on the surface, in this case imparting an air of quiet, concealed menace to the proceedings:

“If you were an eagle, among your hereditary clouds, and looked down upon Vaalafiel, you would see that it is coiled up on the sea much in the way a kitten rolls itself together on the hearthrug – the creature’s paws being represented by the narrow belts of land overlapping each other and forming the arms of our Voe (fjord), whose crags are very suggestive of claws!”

The virtues of this novel are in its sharp observation of character and relationships and a certain dry humour which Inga shares with her creator and which, for most of the time, greatly enlivens the narrative.